Abstract

Background

The Apple Watch Series 4 (AW4) and the KardiaMobile single bipolar lead model (KM) are 2 of the most popular US Food & Drug Administration (FDA)-approved commercial heart trackers. However, a lack of knowledge remains regarding their rhythm-detection accuracy in real-life clinical situations. This paper aims to determine the practicality of using an AW4 or a KM in modern medical practice, by assessing the accuracy of each in identifying heart rhythms and heart rate.

Methods

Participants from the Toronto Heart Centre clinic were enrolled from January 2019 to December 2019. They had a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), followed by wearing the AW4 watch (OS 5.3), and pressing on the KM electrode plates, within the span of 5 minutes of one another. Each session involved a 12-lead ECG, an ECG from each device, and AW4’s photoplethysmography function (APPG).

Results

Of 200 participants, 162 (81%) were in sinus rhythm, and 38 (19%) had atrial fibrillation. The rhythm-detection accuracy for sinus rhythm was 100% for the AW4, and 99.03% for the KM. For atrial fibrillation, accuracy was 90.48% for the AW4, and 100% for the KM. The heart rate accuracy for sinus rhythm was 94.39% for the KM, 90.65% for the APPG, and 96.26% for the Apple ECG function. The heart rate accuracy for atrial fibrillation was 91.30% for the KM, 82.61% for the APPG, and 86.96% for the Apple ECG function.

Conclusions

Both the AW4 and the KM could reliably detect rhythm and heart rate in real-life clinical situations. However, a nonsignificant trend occurred toward better rhythm detection and accuracy with KM, compared with AW4. The difference is mainly due to artifacts (eg, tremors) and the fit of the strap for AW4. The findings have important implications for how these consumer devices can be used in real-life clinical settings.

Graphical abstract

Résumé

Contexte

La Apple Watch Series 4 (AW4) et le dispositif KardiaMobile à trois électrodes (KM) sont deux des capteurs cardiaques commerciaux les plus populaires approuvés par la Food & Drug Administration (FDA) des États-Unis. Cependant, les connaissances sont encore insuffisantes en ce qui concerne leur précision à détecter le rythme cardiaque dans des situations cliniques réelles. Cet article vise à déterminer l’utilité de l’AW4 ou du KM dans la pratique médicale moderne, en évaluant la précision de chaque appareil dans la perception des rythmes cardiaques et de la fréquence cardiaque.

Méthodologie

Des patients du Toronto Heart Centre ont participé à l’étude de janvier à décembre 2019. Ils ont subi un électrocardiogramme (ECG) à 12 dérivations, puis ont porté la montre AW4 (OS 5.3) et utilisé les électrodes du KM, à intervalles de 5 minutes. Chaque séance comprenait un ECG à 12 dérivations, un ECG réalisé avec chacun des dispositifs et l’utilisation de la fonction de photopléthysmographie de l’AW4.

Résultats

Sur les 200 participants, 162 (81 %) étaient en rythme sinusal et 38 (19 %) présentaient une fibrillation auriculaire. Pour ce qui est du rythme cardiaque, la précision de détection chez les patients en rythme sinusal était de 100 % pour l’AW4 et de 99,03 % pour le KM. Pour ceux présentant une fibrillation auriculaire, la précision était de 90,48 % pour l’AW4 et de 100 % pour le KM. En ce qui concerne la fréquence cardiaque, la précision de détection pour le rythme sinusal était de 94,39 % pour le KM, de 90,65 % pour la fonction de photopléthysmographie de l’AW4 et de 96,26 % pour la fonction ECG d’Apple. Chez les patients atteints de fibrillation auriculaire, la précision à détecter la fréquence cardiaque était de 91,30 % pour le KM, de 82,61 % pour la fonction de photopléthysmographie de l’AW4 et de 86,96 % pour la fonction ECG d’Apple.

Conclusions

L’AW4 et le KM ont tous deux permis de détecter de manière fiable le rythme cardiaque et la fréquence cardiaque dans des situations cliniques réelles. Soulignons toutefois qu’une tendance non significative s’est dégagée en faveur du KM pour ce qui est de la détection du rythme et de la précision par rapport à l’AW4. La différence s’explique principalement par des interférences (secousses) et par l’ajustement du bracelet avec l’AW4. Ces résultats ont une incidence importante quant à l’utilisation de ces appareils destinés aux consommateurs dans un contexte clinique réel.

One of the most popular personal health technologies is the smartwatch, namely the Apple Watch (Apple, Inc., Cupertino, CA). In fact, global smartwatch production grew substantially in 2021, reaching an excess of 40 million units, the largest quarterly shipment ever.1 We decided to focus on the Apple Watch Series 4 (AW4; Apple, Inc.) due to its popularity on digital and watch blogs and because it was the leader in smartwatch sales, accounting for almost a third of the worldwide smartwatch market in quarter 4 of 2021.2

The AW4 implements 2 methods to detect heart rate (HR) and rhythm—photoplethysmography (PPG) and a 2-lead electrocardiogram (ECG). PPG is an affordable, noninvasive technique that uses several green light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and optical sensors to measure changes in blood volume.3 The AW4 PPG function (APPG) provides long-term surveillance of HR. Additionally, the AW4’s user-triggered ECG (AECG) recording is activated via 2 installed electrodes, one in the digital crown and the other in the back of the watch.4

For the KardiaMobile (KM) (AliveCor Inc., San Francisco, CA), by contrast, a more focused approach has been used in the design; it comprises only a single bipolar lead that resembles lead I in a 12-lead ECG. However, the seemingly simple ECG mechanism uses a deep neural network-trained artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm with ECG data from over 200,000 Mayo Clinic patients.5

Despite the widespread popularity of smartwatches, consumer reports and clinical studies often have been contradictory in their claims about device accuracy. For example, one report claims that the AW4 has high accuracy.6 In contrast, some cardiologists have raised concerns about the Apple Watch’s inability to differentiate between long-term vs short-term arrhythmias, emphasizing the danger of presenting users with false positives.7 Many studies have demonstrated the high accuracy of the KM.8, 9, 10, 11 Yet, complaints regarding its practicality have been made, such as the need for wearers to be perfectly still when using the device and its inability to provide continuous monitoring.12

We aimed, therefore, to determine the practicality of incorporating digital health devices, specifically the AW4 and the KM, into contemporary medical practice, by assessing and comparing their accuracies in identifying heart rhythm and HR.

Methods

A total of 200 participants were recruited from the Toronto Heart Centre, a community-based cardiology clinic in downtown Toronto (Ontario, Canada), between January 2019 and December 2019, all of whom were scheduled for a new consultation or a routine follow-up visit.

The study team (C.L., C.L., C.M.C.) recruited potential participants, and those who signed the informed consent form underwent their usual scheduled 12-lead ECG. Immediately afterward, they were asked to sit down and were properly fitted with both the AW4 and the KM for the study duration. The AW4 was strapped onto the wrist of their nondominant hand, in the typical position of a wristwatch, ensuring that it rested snugly against their skin. The participants were instructed to use the ECG and HR functions on the AW4, taking 2 sets of 30-second readings for each mode. Next, the participants were instructed to hold the KM with both hands such that both their thumbs touched the sensors, taking 2 sets of 30-second readings. The first set of recordings was used to test for proper strap fit and to teach the patients how to use the device, and the second set was used for the study. The HR trackers were thoroughly cleaned and disinfected after each use. Approval was obtained from the Vertias Institutional review board (protocol no. 16450-17), Montreal, Quebec, on October 21, 2019. A blinded review of the HR recordings was not employed, so that the patients could use the devices as naturally and realistically as possible.

Data collection

We obtained the patients’ demographic information, medical history, risk factors, current treatment record, and reasons for referral by interviewing the patients and reviewing their health records. We also noted patients’ awareness of the ability of the digital health devices to detect HR and heart rhythm. Patient identifiers included name, gender, date of birth, and medical record number. These identifiers were required to access patients’ clinical records for later review.

Statistical analysis

The 12-lead ECG recordings were interpreted by a cardiologist (C.M.C.) who was blinded to the reported findings of the AW4 and the KM. Whenever indicated, data were presented as a percentage of patients; AW4 and KM rhythm diagnoses were considered accurate if they matched the rhythm detected by the 12-lead ECG. HR readings were considered correct if they deviated a maximum of ± 5 beats per minute from the 12-lead ECG, taking into account variability in atrial fibrillation (AF). Rates were analyzed using χ2 tests to compare the devices, with a P value of < 0.05 accepted as statistically significant. Additionally, Cohen’s kappa coefficients were calculated for device accuracy in detecting heart rhythm, sinus rhythm (SR), and AF. Continuous data were analyzed using independent-samples t-tests. We used the statistical software SAS Enterprise Guide 6.1 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Demographic data

A total of 200 participants were recruited from the Toronto Heart Centre, of which 41% (82) were women. The mean age was 65.6 years, with a standard deviation of ± 14.6, with the youngest being 26 years and the oldest 94 years. Few (41%) were aware of the AW4’s ability to record ECGs, and even fewer (3%) were aware of the KM’s ability to do so. Overall, 81% of participants (162) were in SR, and 19% (38) were in AF.

A Shapiro-Wilk test was performed and did not show evidence of non-normality (W = 0.987, P = 0.215). Parametric tests for comparisons were used based on this outcome. A summary of the demographic data for the 200 participants is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Demographic variable | AW4 (average) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 65.6 ± 14.6 |

| Sex, male | 59.2 |

| Hypertension | 49.6 |

| Diabetes | 18.5 |

| Dyslipidemia | 41.5 |

| Coronary artery disease | 3.7 |

| Stroke/TIA | 0.7 |

| Vascular disease | 0.7 |

| Awareness of AW4’s ECG function | 41 |

| Awareness of KM’s ECG function | 3 |

Values are %, unless otherwise indicated.

AW4, Apple Watch Series 4 (Apple, Inc, Cupertino, CA); ECG, electrocardiogram; KM, KardiaMobile (AliveCor, San Francisco, CA); TIA, transient ischemic attack.

The SR detection accuracy was 100% for the AW4, and 99% for the KM. No inconclusive SR readings occurred with the AW4, but 2 inconclusive readings occurred with the KM. The AF detection accuracy was 90.5% with the AW4, and 100% with the KM. The AW4 had 19 inconclusive AF readings, whereas the KM had none. Cohen’s kappa coefficients (k) for correctly identifying heart rhythm were 0.966 and 0.969 for the AW4 and KM, respectively.

SR HR accuracies for the devices were as follows: 96.5% for the AECG, 90.5% for the APPG, and 94% for the KM. There were 7 inconclusive SR HR readings for the AECG, 19 for the APPG, and 12 for the KM. AF HR accuracies were as follows: 87% for the AECG, 83% for the APPG, and 91% for the KM. A total of 26 inconclusive AF HR readings occurred for the AECG, 34 for the APPG, and 18 for the KM.

Discussion

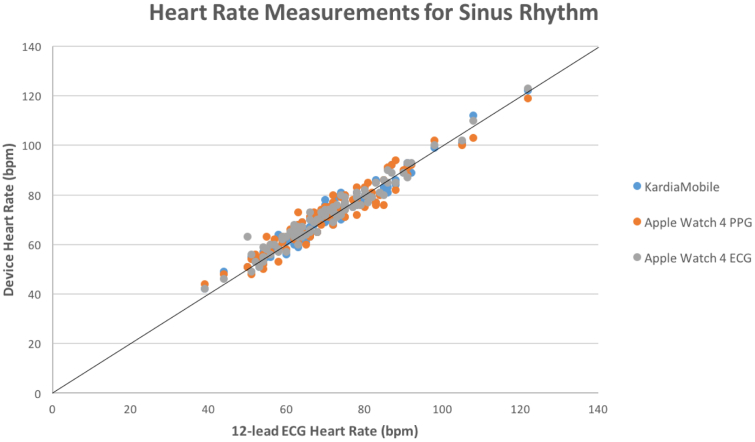

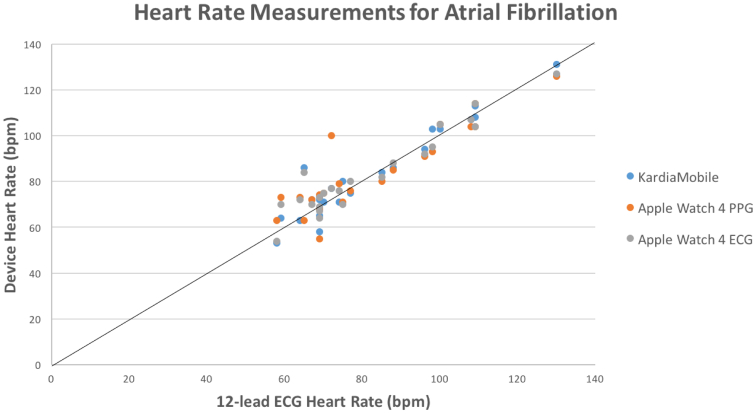

This study demonstrates that the AW4 and KM are both capable digital health devices that can reliably and accurately detect heart rhythm and HR. Both devices performed superbly in detecting SR (100% for the AW4 and 99% for the KM), as shown in Figure 1. With AF, the rhythm detection performance decreased with the AW4 (90.5%) but not with the KM (100%). For assessment of HR in SR, the ECG method was highly accurate with both the AW4 (96.5%) and the KM (90.5%), as shown in Figure 2. With the PPG method used by the AW4, HR measurements were slightly more variable (90.5%) than those with the ECG method. For patients with AF, HR detection variability was even higher, which may be attributable to the slight time differences between the ECG and the mobile device recordings (87% for the AECG, 83% for the APPG, and 91% for the KM).

Figure 1.

Bar graph of percent of rhythms correctly identified by the Apple Watch Series 4 (AW4) and and the Kardia Mobile (KM). Afib, atrial fibrillation.

Figure 2.

Bar graph of heart rate accuracies for sinus rhythm and atrial fibrillation (Afib) for each device method. ECG, electrocardiogram; PPG, photoplethysmography.

The heart rhythm results show that SR was detected with greater overall accuracy than was AF. This result was similarly demonstrated in multiple studies that noted decreased accuracy in digital health devices’ HR readings for patients with AF, leading particularly to underestimation in HR readings.13,14 A likely explanation for this discrepancy is the ease of detecting the regularly occurring intervals of QRS complexes in SR, rather than the irregularly occurring intervals of QRS complexes in AF. Therefore, the devices’ rhythm detection formulas would make calculations easily based on the more stable SR dataset. However, consideration of each device's rhythm detection indicated that the AW4 was more accurate for SR detection.

In contrast, the KM was more accurate for AF detection, and this can be attributed to differences in the AI programs used by the 2 devices. Each program has characteristics that allow its respective device to achieve a higher degree of accuracy in a particular heart rhythm, due to differences such as ECG datasets.15 Another possible explanation for the AW4’s lower AF rhythm detection is that its AI program misinterpreted certain rhythm variations16; for example, in the case of 2 patients, the AW4 recorded AF that was later confirmed to be premature atrial complexes (PACs).

The devices’ HR results also show a higher accuracy for SR than for AF, as compared in Figures 3 and 4, respectively. A factor that may have contributed to the relatively lower accuracy of the AF patients’ HR readings was the difficulty associated with elderly patients.17 As reported in a study that examined the management of AF patients,18 most AF patients are elderly. These patients often presented with tremors, which created artifacts in the ECG recordings. Elderly female patients in particular presented with the issue of having improper strap fit for the AW4, as even the smallest available Apple Watch strap was too large on their wrists. Given that the AW4 relies on its sensors being pressed snugly against the wearer’s skin in order for the PPG and ECG methods to work properly, both methods for the AW4 would have decreased accuracy with an ill-fitting strap. Of note, although the KM could have provided better readings than previous versions, it was not available for purchase by the time this study was conducted. This device warrants further study.

Figure 3.

Scatter plot of measured heart rates vs true heart rates in patients with sinus rhythm. Solid line represents perfect accuracy (R2 = 1). bpm, beats per minute; ECG, electrocardiogram; PPG, photoplethysmography.

Figure 4.

Scatter plot of measured heart rates vs true heart rates in patients with atrial fibrillation. Solid line represents perfect accuracy (R2 = 1). bpm, beats per minute; ECG, electrocardiogram; PPG, photoplethysmography.

Examination of the 2 AW4 methods showed that the APPG function performed the worst when measuring HR. This finding was similar to results of previous studies,19,20 with PPG being less accurate than ECG, especially in situations requiring increased physical activity. Another drawback in the practicality of using PPG for HR recordings is that a decrease in temperature, such as exposure to cold weather, will affect the detection of heart complexes by making the fiducial point more difficult to locate.21 Lastly, PPG has been found to have greater inaccuracy for users with darker skin tones.22

An examination of patient demographic factors revealed that gender and age influenced device accuracy. As shown in Figure 5, the accuracy of the KM heart rhythm detection was high for both genders, but no significant difference between genders was seen. On the contrary, the accuracy of the AW4 rhythm detection was slightly lower than that of the KM, and women experienced lower rates of rhythm detection than men.

Figure 5.

Bar graph of percent of rhythms correctly identified, by gender.

Further research

A possible approach to further investigation is to take ECG recordings throughout various physical activity intensities. Such data would provide valuable information for those seeking to measure and interpret their HR and rhythm recordings during and immediately after activities that are physiologically stressing, such as an exercise workout. Incorporation of the newer KM device could reveal whether the addition of leads would result in significant improvements in HR and rhythm detection. Lastly, sampling from a population that includes a greater number of younger patients would be beneficial, in order to be inclusive of a larger portion of the consumer market for these devices.

Limitations

Although the study has strengths, it is not without limitations. Due to the constraints of the clinical operation at the Toronto Heart Centre, the device recordings had to be taken in sequence; the 12-lead ECG was used first, followed by the 2 AW4 modes (AECG and APPG), and finally the KM. Ideally, these should be used simultaneously to achieve more comparable results. However, to limit the variation of HR, each of the recordings was taken once the patients returned to their resting state. All the readings were completed within 1-2 minutes of each other.

Another limitation was that the ECG recordings were taken only at rest, as both the AW4 and the KM gave suboptimal ECG recordings when participants moved their hands. As a result, motion artifacts often presented in the ECG recordings as unsuccessful recordings. In such cases, an error message appeared, and the recording had to be repeated.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the AW4 and the KM can reliably and accurately detect heart rhythm and HR, supporting previous findings demonstrating the capacity of these digital health devices for use in patient screening and monitoring.23 Although the ECG function on the AW4 is more accurate than the PPG function, it does have greater limitations in terms of artifacts. Of note, the AW4 costs $519, and the KM costs $99 (both in Canadian dollars),24,25 yet the AW4 can be operated from the wrist alone, whereas the KM requires the additional use of a smartphone.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

The project is entirely self-funded, as the devices were purchased directly from the open market by the authors. The authors have no funding sources to declare.

Disclosures

None of the authors have collaborated with or are affiliated with Apple Inc. or AliveCor Inc. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Ethics Statement: Approval was obtained from Vertias institutional review board (Protocol no. 16450-17), Montreal, Quebec on October 21, 2019. The research reported has adhered to the relevant ethical guidelines.

See page 944 for disclosure information.

References

- 1.Lim S. Smartwatch market grows 24% YoY in 2021, records highest ever quarterly shipments in Q4. Available at. https://www.counterpointresearch.com/global-smartwatch-market-2021/

- 2.ReportLinker. Global smartwatch market—growth, trends, COVID-19 impact, and forecasts (2021-2026). Available at: https://www.reportlinker.com/p06187407/Global-Smartwatch-Market-Growth-Trends-COVID-19-Impact-and-Forecasts.html?utm_source=GNW. Accessed March 6, 2022.

- 3.Allen J. Photoplethysmography and its application in clinical physiological measurement. Physiol Meas. 2007;28:1–39. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/28/3/R01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apple Inc. Take an ECG with the ECG app on Apple Watch. Available at. https://support.apple.com/en-ie/HT208955

- 5.AliveCor Three new studies confirm clinical utility of AliveCor’s KardiaMobile device and AI algorithms. Available at. https://www.alivecor.com/press/press_release/three-new-studies-confirm-clinical-utility-of-alivecors-kardiamobile-device-and-ai-algorithms/

- 6.Falter M., Budts W., Goetschalckx K., Cornelissen V., Buys R. Accuracy of Apple watch measurements for heart rate and energy expenditure in patients with cardiovascular disease: cross-sectional study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7 doi: 10.2196/11889. e11889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Husten L. Beware the hype over the Apple Watch heart app. The device could do more harm than good. Available at: https://www.statnews.com/2019/03/15/apple-watch-atrial-fibrillation/. Accessed February 4, 2020.

- 8.Giebel G.D., Gissel C. Accuracy of mHealth devices for atrial fibrillation screening: systematic review. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2019;7 doi: 10.2196/13641. e13641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koltowski L., Balsam P., Glłowczynska R., et al. Kardia Mobile applicability in clinical practice: a comparison of Kardia Mobile and standard 12-lead electrocardiogram records in 100 consecutive patients of a tertiary cardiovascular care center. Cardiol J. 2021;28:543–548. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2019.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gropler M.R.F., Dalal A.S., Hare G.F.V., Silva J.N.A. Can smartphone wireless ECGs be used to accurately assess ECG intervals in pediatrics? A comparison of mobile health monitoring to standard 12-lead ECG. Plos One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204403. e0204403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.William A.D., Kanbour M., Callahan T., et al. Assessing the accuracy of an automated atrial fibrillation detection algorithm using smartphone technology: the iREAD study. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15:1561–1565. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Slooten T. AliveCor Kardia Mobile heart monitor review 2018. Available at. https://www.livingwithatrialfibrillation.com/1961/alivecor-kardia-monitor-review/

- 13.Al-Kaisey A.M., Koshy A.N., Ha F.J., et al. Accuracy of wrist-worn heart rate monitors for rate control assessment in atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2020;300:161–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.11.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koshy A.N., Sajeev J.K., Nerlekar N., et al. Smart watches for heart rate assessment in atrial arrhythmias. Int J Cardiol. 2018;266:124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han C., Song Y., Lim H.-S., et al. Automated detection of acute myocardial infarction using asynchronous electrocardiogram signals—preview of implementing artificial intelligence with multichannel electrocardiographs obtained from Smartwatches: retrospective study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23 doi: 10.2196/31129. e31129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yazdi D. The Apple Watch 4 is an iffy atrial fibrillation detector in those under age 55. Available at. https://www.statnews.com/2019/01/08/apple-watch-iffy-atrial-fibrillation-detector/#:∼:text= In%20people%20younger%20than%2055,79.4%20percent%20of%20the%20time

- 17.Stone J.D., Ulman H.K., Tran K., et al. Assessing the accuracy of popular commercial technologies that measure resting heart rate and heart rate variability. Front Sports Act Living. 2021;3:585870. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2021.585870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Letsas K., Karamichalakis N., Vlachos K., et al. Managing atrial fibrillation in the very elderly patient: challenges and solutions. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2015;11:555–562. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S83664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonçalves H., Pinto P., Silva M., Ayres-De-Campos D., Bernardes J. Electrocardiography versus photoplethysmography in assessment of maternal heart rate variability during labor. Springerplus. 2016;5:1079. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2787-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghamari M. A review on wearable photoplethysmography sensors and their potential future applications in health care. Int J BiosensBioelectron. 2018;4:195–202. doi: 10.15406/ijbsbe.2018.04.00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vescio B., Salsone M., Gambardella A., Quattrone A. Comparison between electrocardiographic and earlobe pulse photoplethysmographic detection for evaluating heart rate variability in healthy subjects in short- and long-term recordings. Sensors. 2018;18:844. doi: 10.3390/s18030844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bent B., Goldstein B.A., Kibbe W.A., Dunn J.P. Investigating sources of inaccuracy in wearable optical heart rate sensors. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:18. doi: 10.1038/s41746-020-0226-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Godin R., Yeung C., Baranchuk A., Guerra P., Healey J.S. Screening for atrial fibrillation using a mobile, single-lead electrocardiogram in Canadian Primary Care Clinics. Can J Cardiol. 2019;35:840–845. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2019.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.iphone in Canada Apple Watch Series 4 pricing in Canada starts at $519 CAD [u]. Available at. https://www.iphoneincanada.ca/watch/apple-watch-series-4/#:∼:text=Apple%20will%20release%20the%20Apple,models%20starting%20at%20%24649%20CAD

- 25.Amazon.ca. Alivecor KardiaMobile ECG Monitor: Wireless personal ECG device: Detect afib from home in 30 seconds. Available at: https://www.amazon.ca/Alivecor-AL-KARDIAMOBILE-Kardia-Mobile/dp/B01A4W8AUK/ref = sr_1_5?crid = 36H8J7TSI5UTJ&keywords = kardiamobile&qid = 1647696319&sprefix = kardiamobile%2B%2Caps%2C158&sr = 8–5. Accessed March 19, 2022.