Summary

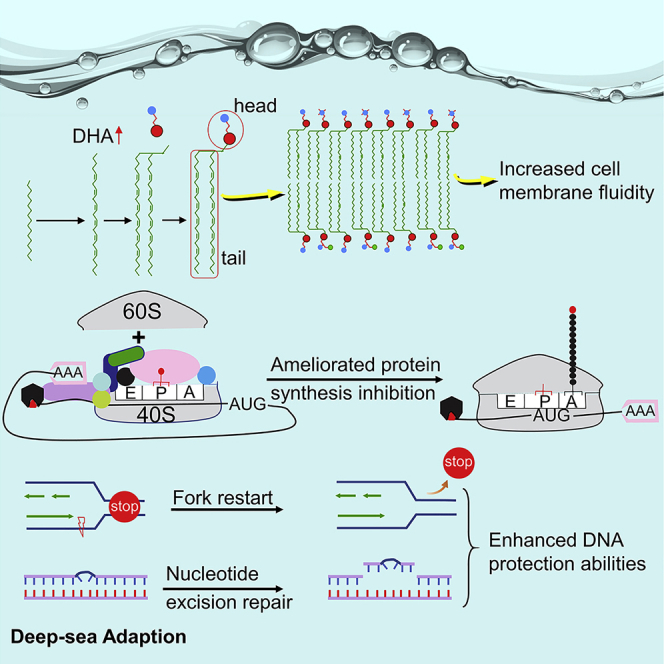

How organisms cope with coldness and high pressure in the hadal zone remains poorly understood. Here, we sequenced and assembled the genome of hadal sea cucumber Paelopatides sp. Yap with high quality and explored its potential mechanisms for deep-sea adaptation. First, the expansion of ACOX1 for rate-limiting enzyme in the DHA synthesis pathway, increased DHA content in the phospholipid bilayer, and positive selection of EPT1 may maintain cell membrane fluidity. Second, three genes for translation initiation factors and two for ribosomal proteins underwent expansion, and three ribosomal protein genes were positively selected, which may ameliorate the protein synthesis inhibition or ribosome dissociation in the hadal zone. Third, expansion and positive selection of genes associated with stalled replication fork recovery and DNA repair suggest improvements in DNA protection. This is the first genome sequence of a hadal invertebrate. Our results provide insights into the genetic adaptations used by invertebrate in deep oceans.

Subject areas: Zoology, Genetics, Evolutionary mechanisms, Genomics

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

The genome of hadal sea cucumber Paelopatides sp. Yap was sequenced and characterized

-

•

Altering the content of DHA and phosphatidylethanolamine is a way to deep-sea adaptation

-

•

Paelopatides sp. Yap enhanced DNA protection abilities for high-pressure adaptation

-

•

Paelopatides sp. Yap evolved to ameliorate protein synthesis inhibition in the hadal zone

Zoology; Genetics; Evolutionary mechanisms; Genomics

Introduction

The hadal zone lies at the bottom of the deepest oceanic trenches at depths of 6,000-11,000 m. This deep-sea environment is characterized by food shortage, darkness, hypoxia, low temperature, and high hydrostatic pressure.1 Hydrostatic pressure, which increases by approximately one atmosphere for every 10 m increment in-depth, strongly constrains the vertical distribution of marine organisms. The effects of high hydrostatic pressure on cell physiology are pleiotropic and primarily include reduction in cell membrane fluidity,2,3 inhibition of protein synthesis,4,5 and replication fork stalling and DNA damage.6,7,8,9 Low temperature has similar inhibitory effects on cell membrane fluidity10 and protein synthesis.11,12 Nevertheless, many diverse groups of organisms survive and thrive in the hadal zone.1,13,14 However, the adaptive mechanisms of these organisms for the hadal environment were poorly understood. Recently, two genomes of the hadal snailfish from the Mariana Trench and Yap Trench were reported, and pressure-tolerant cartilage, enhanced cell membrane fluidity and transport protein activity, increased protein stability and DNA repair have been suggested to be associated with hadal adaption,15,16 which provided paradigms for genetic adaptation to the hadal environment. Nevertheless, due to a lack of genomic data for hadal species, it remains largely unclear how these organisms cope with their hostile hadal environment.

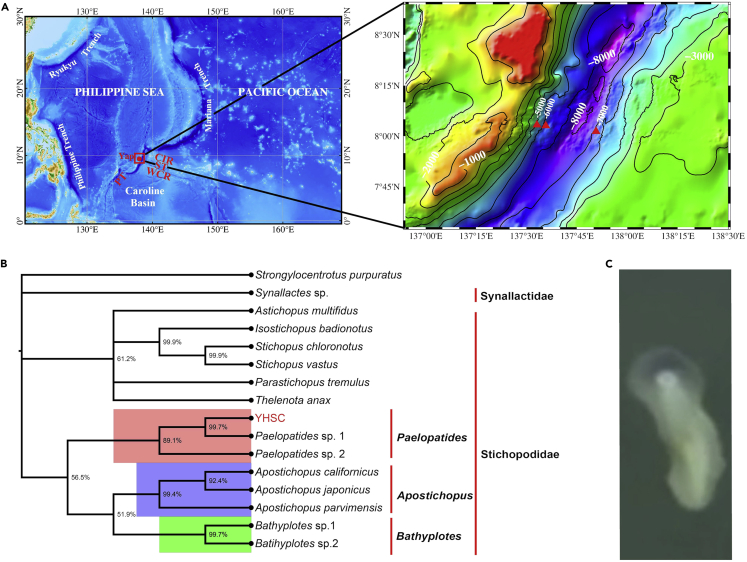

The Yap Trench lies in the western Pacific Ocean and neighbors the Mariana Trench. In June 2017, three sea cucumbers were collected in the Yap Trench using the Jiaolong Manned Submarine at depths of 5,090 m, 6,429 m, and 6,633 m and at 1.49-1.71°C (Figure 1A and Table S1). These specimens were preliminarily designated "Yap hadal sea cucumbers" (YHSCs). In this study, we sequenced and characterized the genome of a YHSC collected at 6,633 m. We then explored the strategies employed by YHSCs for deep-sea adaption.

Figure 1.

YHSC capture locations, phylogenetic position, and morphology

(A) Location of the Yap Trench (left) and the sampling points ( ) on a bathymetric map (right). YAP: Yap Trench; CIR: Caroline Islands Ridge; ST: Sorol Trough; WCR: West Caroline Rise; and PT: Palau Trench.

) on a bathymetric map (right). YAP: Yap Trench; CIR: Caroline Islands Ridge; ST: Sorol Trough; WCR: West Caroline Rise; and PT: Palau Trench.

(B) Bayesian inference tree based on three concatenated nuclear genes: 18S rRNA, 28S rRNA, and H3. The numbers at nodes represent the bootstrap scores.

(C) Gross morphology of YHSC.

Results and discussions

Yap hadal sea cucumbers genome characteristics

In this study, approximately 209.1 Gb Illumina clean reads were produced from genome sequencing and used to estimate the genomic characteristics. The estimated size is 3.54 Gb with a repeat content of 73.93% and a heterozygosity rate of 2.9% (Figure S1, and Table S2). Then, PacBio sequencing generated 490.9 Gb subreads (Table S3), with a depth of 133×. These subreads were assembled into 59,054 contigs, of which 2740 were identified as redundant sequences and excluded. GC depth scatterplots were used to evaluate the contamination in the sequencing data. No interruptions were detected along the horizontal axis of the GC-depth scatterplot, indicating no obvious sample contamination (Figure S2). Nevertheless, 876 contigs were identified as bacterial contamination and were ruled out (Table S4). The final genome consists of 55,447 contigs with a total size of 3.70 Gb and an N50 of 137.1 kb (Table S5). The small gap between the estimated size and final size can result from low estimation accuracy, considering the serious effects of repeats and high heterozygosity on the accuracy of genome size estimation.17,18 Additionally, it took more than 3 h for the submarine to bring the specimens from the sampling site to the mothership, during which the specimens suffered a high level of DNA damage. The peak size of the DNA sample is only 15,860 bp and the DNA integrity number (DIN) is 6.7 (Figure S3). The DNA damage is mainly caused by rapid and prolonged decompression stress during specimen collection as previously indicated,7 which prevented us from further assembling the contigs into scaffolds by conducting Hi-C,19 Chicago20 or Bionano.21 Read mapping rate is an important metric assessing the completeness of assembly.22,23 In this study, approximately 99.11% of the Illumina reads were successfully mapped to the polished contigs, reflecting the completeness of the YHSC genome assembly (Table S6). We identified 89.4% complete benchmarking universal single-copy orthologs (BUSCOs) in the genome assembly (Table S7), again reflecting high genome integrity. In addition, 57,522 genes were successfully annotated using a combination of homology-based predictions, ab initio gene prediction, and transcript evidence in YHSC (Table S8).

Phylogenetic position and evolutionary history of the Yap hadal sea cucumbers

Blastn searches against the NCBI nt database indicated that the nucleic acid sequences of two mitochondrial genes—16S rRNA gene (16S rRNA) and cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI), and three nuclear genes—18S rRNA gene (18S rRNA), 28S rRNA gene (28S rRNA) and histone H3 (H3) from the YHSC were most similar to the corresponding genes from the deep-sea holothurian Paelopatides sp. 1.24 Multigene phylogenies of the extant Holothuroidea based on the three nuclear genes or the two mitochondrial genes (Table S9) showed that the YHSC formed a clade with Paelopatides sp. 1 and Paelopatides sp. 2, suggesting that the YHSC may fall into this genus (Figures 1B, S4A-S4B). To test this possibility, we calculated the genetic divergence between the YHSC and seven closely related species in Paelopatides, Bathyplotes, and Apostichopus based on the COI barcoding gene (Table S10). Across all seven comparisons, only the genetic distance between the YHSC and Paelopatides sp. 1 (1.05) and the genetic distance between the YHSC and Paelopatides sp. 2 (11.87) were within the range typical of congeneric divergences in Holothuroidea (2.16-17.02; mean: 12.41).25 Thus, we hypothesize that the YHSC falls into the Paelopatides rather than the Bathyplotes or Apostichopus. In all phylogenies, Paelopatides, Bathyplotes, and Apostichopus formed a clade corresponding to Stichopodidae (Figures 1B, S4A-S4B), consistent with the transfer of Paelopatides and Bathyplotes to Stichopodidae in the recent revision.24 However, it should be noted that the assignment of the YHSC to Paelopatides within Stichopodidae remains tentative. For one thing, the molecular data of many other genera in Stichopodidae except for those mentioned above is still lacking; for another, the monophyly of Paelopatides has not been confirmed, and the morphology of Paelopatides sp. 1, Paelopatides sp. 2, and YHSC has not been checked.

In appearance, the YHSC is sub-cylindrical. Except for a small area at one end, the whole body of YHSC is translucent white (Figure 1C and Video S1). Dated phylogenetic trees of Holothuroidea based on different calibration points are highly incongruent.24 However, the two possible divergence times between Apostichopus and Paelopatides have been estimated to be 74 or 91 million years ago (Ma),24 which substantially predated the formation of the Yap Trench (40 Ma).26,27,28,29 This suggested that the YHSC diverged from Apostichopus japonicus before colonizing the hadal zone.

Inference of whole genome duplication

In the consideration of the high gene number in the YHSC genome, whole genome duplications (WGDs) were inferred from Ks age distribution. The whole paranome Ks distributions for both A. japonicus and YHSC are typically L-shaped until at least the Ks peak of their orthologs (Figure S5), indicating that YHSC didn’t experience any WGDs after its differentiation with A. japonicus according to previous interpretation.30,31 Thus, YHSC should be diploid, given that A. japonicus has a diploid genome.32,33

Comparative genomics

We used CAFÉ (4.2)34,35 to characterize the expansion and contraction of gene families in the YHSC genome compared with six other invertebrate genomes: Drosophila melanogaster, Saccoglossus kowalevskii, Strongylocentrotus purpuratus, A. japonicus, and two geographically separated populations of Acanthaster planci (Okinawa, Japan, and the Great Barrier Reef, Australia).36 A total of 6030 and 2730 gene families are significantly expanded and contracted in the YHSC genome, respectively (Figure S6A). Thus, the gain-to-loss ratio of gene families is 2.2 (6030/2730). Comparisons of pfam functional domains among the seven invertebrate genomes suggested that the YHSC has the highest percentage of unique domains (Figure S6B). We identified 173 expanded domains in the YHSC genome (Table S11). The cutoff for expanded domains can be found in the quantification and statistical analysis section. These expanded domains were associated with many important biological processes, including transposons, genetic information processing, immunity, material transport, apoptosis, metabolism, and DNA binding (Figure S7).

Although it is routine that the identification and masking of repeats are performed before the gene prediction, repeat identification tools available at present can not totally find and mask all the repeats.37 This is exactly the case for the YHSC genome with a high proportion of repeats. In this study, 24 of the 173 expanded domains exist in transposon-encoded proteins (Table S11). Although this proportion is low, the 24 expanded domains are involved in 9104 YHSC genes, accounting for 62.5% of the YHSC genes that contain at least one of the 173 expanded domains (14,578). Thus, increased gene number in the YHSC genome (57,522) compared with other echinoderm genomes (30,250 genes for A. japonicus, 24,743 genes for A. planci, 28,886 genes for S. purpuratus) mainly resulted from partial identification and incomplete masking of transposons during gene identification.

Convergent sequence evolution between the Yap hadal sea cucumbers and Pseudoliparis swirei

To determine whether convergent evolution occurs between YHSC and the hadal snailfish P. swirei,16 we identified and compared their positively selected genes (PSGs). Positive selection analysis using the site-branch model in codeml identified 441 PSGs in the YHSC genome taking three closely related shallow-sea species of Holothuroidea (Parastichopus parvimensis, Stichopus horrens, and A. japonicus) as background branches. We also identified 397 PSGs in P. swirei using three shallow-sea fishes (Paralichthys olivaceus, Gasterosteus aculeatus, and Liparis tanakae) as background branches. Six PSGs were shared by the YHSC and P. swirei: ethanolamine phosphotransferase 1 (EPT1), nucleoporin 43 (NUP43), sorting nexin-17 (SNX17), mitochondrial ribosomal protein S27 (MRPS27), alpha-1,3- mannosyltransferase (ALG3), and XPC complex subunit, DNA damage recognition and repair factor (XPC), which are involved in the synthesis of phosphoethanolamine38 (one of the most abundant phospholipids in cell membranes), mitosis and assembly of the nuclear pore complex,39 sorting of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1,40 mitochondrial ribosome, protein glycosylation,41 and DNA repair,42 respectively (Table S12). Due to the distant genetic relationships, no overlapping amino acid sites in the six PSGs between YHSC and P. swirei were identified. Nevertheless, these six genes were also considered to have experienced convergent positive selection since they evolved under selection in both organisms, even though their sequences have not converged at the amino acid level. Interestingly, most pathways or components in which these convergent genes are involved, such as cell membrane fluidity, mitosis, ribosome, and DNA repair, are destroyed by high pressure and low temperature in the hadal zone.

Repeat expansion in the Yap hadal sea cucumbers genome

Compared with the genomes of A. japonicus, S. purpuratus, and A. planci, the YHSC genome is highly repetitive. Approximately 76.06% of the YHSC genome namely 2.82 Gb was repeats, far exceeding those of the other echinoderm genomes (28.36-48.43%, 0.11-0.45Gb, Table S13). Thus, repeats drove the large-scale genome expansions in YHSC. The main type of the increased repeats in the YHSC genome is transposons, which occupies 58.82% of the YHSC genome, while the corresponding proportion is only 24.43-29.53% for other echinoderm genomes (Table S13). Except DNA transposon, the relative abundances of retroelements, rolling circles and unclassified types in the YHSC genome (16.19%, 2.13 and 38.49%, respectively) are far beyond those of the other genomes (2.93%-5.61%, 0-0.07%, and 14.82-24.15% respectively; Table S13). Among the retroelements identified, the most striking difference between YHSC and the other genomes was the proportion of Gypsy/DIRS1: which accounts for 7.90% of the YHSC genome, a percentage over ten times that of the other genomes (0.30-0.69%; Table S13). Additionally, other retroelements including Penelope, L2/CR1/Rex, RTE/Bov-B, and Retroviral also showed an expansion in the YHSC genome (Table S13). Although the significance of transposable elements in deep-sea adaptation is unknown, transposable elements are considered powerful drivers of genome evolution and phenotypic diversity by introducing genetic changes of great magnitude and variety.43

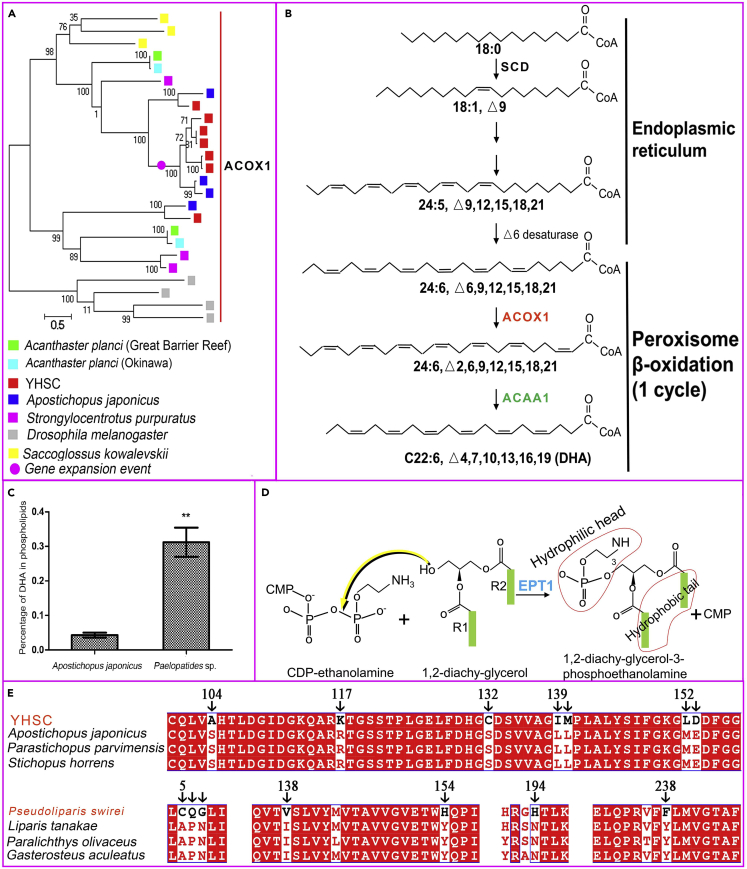

The expansion of the ACOX1 gene for rate-limiting enzyme in the DHA synthesis pathway, the corresponding increase in DHA levels in phospholipids in the Yap hadal sea cucumbers, and the positive selection of the EPT1 gene increased cell membrane fluidity

Fluidity is a fundamental feature of cell membranes and is vital for the execution of various physiological functions. However, both high hydrostatic pressure and low temperature, which are characteristic of the hadal zone, decrease biomembrane fluidity and the ease of phase transitions.44,45 Double bonds in the fatty acid hydrocarbon chain, which constitute the hydrophobic tails of the phospholipid bilayer, can disorder the lipid bilayer and lower the phase-transition temperature.3 (4Z,7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z,19Z)-docosa-4,7,10,13,16,19-hexaenoic acid (DHA, C22:6) has six double bonds and thus can drastically increase cell membrane fluidity.46 In the YHSC genome, acyl-CoA oxidase 1 (ACOX1), a gene encoding rate-limiting enzymes in the DHA synthesis pathway was expanded (Figure 2A). The ACOX1 participates in the first step of β-oxidation in peroxisomes and functions by introducing a trans double bond into acyl chains47,48 (Figure 2B). We identified seven copies of the ACOX1 gene in the YHSC genome and no more than four copies in any of the other genomes examined (Figure 2A). Interestingly, the acetyl-CoA acyltransferase 1 (ACAA1) gene, encoding another rate-limiting enzyme and mediating the last step of DHA synthesis (Figure 2B), expanded in hadal P. swirei.16 The expansion of the ACOX1 gene in the YHSC genome and the ACAA1 gene in hadal P. swirei may accelerate DHA synthesis to counteract the reduction in membrane fluidity associated with the high hydrostatic pressure and low temperature in the hadal zone, and strengthened DHA synthesis represents convergent evolution in the hadal YHSC and P. swirei.

Figure 2.

The adaptive evolution of phospholipids in the cell membrane in the hadal environment

(A) Phylogenetic tree constructed by FastTree (version 2.1.11) using the Jones-Taylor-Thorton (JTT) model of amino acid evolution based on protein sequences containing acyl-coenzyme A oxidase N-terminal (Acyl-CoA_ox_N) show that ACOX1 genes, encoding the rate-limiting enzyme in the DHA synthesis pathway, expanded in the YHSC genome.

(B) DHA synthesis pathway. The ACOX1 in red refers to expansion in the YHSC genome, while the ACAA1 in green, encoding another rate-limiting enzyme, underwent expansion in the hadal snailfish P. swirei.16

(C) DHA content in phospholipids from A. japonicus and the YHSC. ∗∗, p < 0.01 (Student’s t test) Statistical details can be found in the quantification and statistical analysis section.

(D) The production of phosphatidylethanolamine (one of the most abundant components of the cell membrane) catalyzed by EPT1. EPT1 is a gene that experienced convergent evolution between the YHSC and P. swirei.

(E) Multiple sequence alignment of EPT1. Amino acids unique to the YHSC or P. swirei are indicated by arrows.

We analyzed and compared the composition of fatty acids (C6-C24) in the phospholipid bilayer of the YHSC and A. japonicus and found that the relative abundances of four fatty acids differed significantly between the two species: tetradecanoic acid (C14:0), hexadecanoic acid (C16:0), heptadecanoic acid (C17:0), and DHA (Table S14). The fatty acid that differed most substantially between the two species was DHA; DHA content in the YHSC was approximately 7.3 times greater than that in A. japonicus (Figure 2C). This was consistent with the expansion of the ACOX1 gene that encodes the rate-limiting enzyme in the DHA synthesis pathway in the YHSC genome. This suggested that over evolutionary time, the ACOX1 gene encoding the rate-limiting enzyme in the DHA synthesis pathway multiplied in the YHSC genome, increasing DHA content in the phospholipid bilayer to maintain cell membrane fluidity under low temperature and high hydrostatic pressure.

Phospholipids alter membrane fluidity not only via their hydrophobic tails but also via their hydrophilic heads. Phosphatidylethanolamine, which constitutes over half of the total phospholipids in eukaryotic cell membranes38 together with phosphatidylcholine, tends to reduce membrane fluidity due to several characteristics of their head group.49 In this study, we found that EPT1, encoding an enzyme that catalyzes the production of phosphatidylethanolamine38,50 (Figure 2D), underwent convergent positive selection in the hadal-living YHSC and P. swirei (Table S12). Furthermore, many amino acids unique to the YHSC or P. swirei were identified (Figure 2E), which suggested that accelerated mutation in the amino acid sequence of EPT1 may be essential to hadal adaptation.

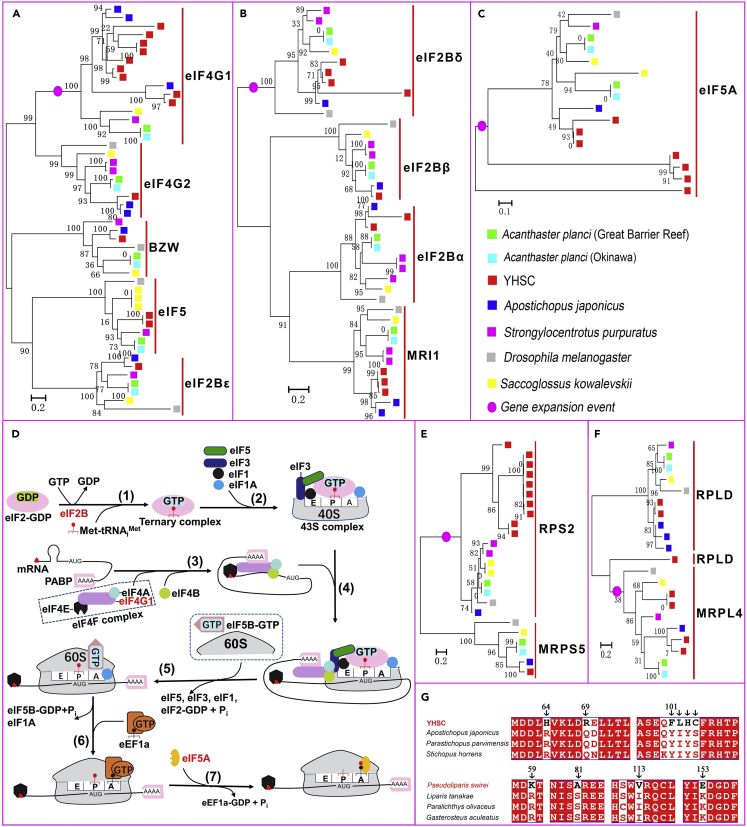

Expansion and positive selection of genes encoding translation initiation factors and ribosomal proteins in the Yap hadal sea cucumbers improved resistance to protein synthesis inhibition

Protein synthesis is the most pressure-sensitive biological process.4 In prokaryotic organisms, the maximum hydrostatic pressure at which organisms can grow is limited by protein synthesis inhibition.51 The step that is most inhibited by hydrostatic pressure in protein synthesis is the binding of aminoacyl-tRNA to the ribosome-mRNA complex; this process requires a large increase in volume, which is prevented by high pressure.4,52,53 High pressure may also lead to ribosome dissociation and further protein synthesis inhibition.54,55,56 Protein synthesis inhibition is also aggravated by low temperature.11,12 Thus, the expansion of genes that promote protein synthesis, bind aminoacyl-tRNA to ribosomes, and maintain the structural integrity of the ribosome may reduce protein synthesis inhibition.

Protein synthesis is mainly regulated at the initiation stage rather than during elongation and termination.57 At least four gene families, in which the YHSC has more members than other species analyzed were involved in the initiation pathway: eIF4-gamma/eIF5/eIF2-epsilon (W2), middle domain of eukaryotic initiation factor 4G (MIF4G), eukaryotic elongation factor 5A hypusine DNA-binding OB fold (eIF-5A), initiation factor 2 subunit family (IF-2B) (Figure S8). Phylogenetic trees of these gene families identified three expanded genes for translation initiation factors in the YHSC (expansion of both W2 and MIF4G is caused by increased copies of the eIF4G1): eukaryotic initiation factor 4 gamma 1 (eIF4G1), eIF2B δ subunit (eIF2Bδ) and eIF5A (Figures 3A-3C). eIF4G1 encodes a “scaffold” protein that can promote translation initiation by binding proteins, including eIF4E, eIF4A, eIF3, and poly(A)-binding protein (PABP)57,58,63 (Figure 3D). A total of 17 copies of eIF4G1 were identified in the YHSC genome; in contrast, no more than three copies were identified in any other genome examined (Figure 3A). In deep-sea fish, eIF4G is positively selected,9 indicating that eIF4G is involved in deep-sea adaptation. The eIF2Bδ gene encodes a subunit of eIF2B, which catalyzes the formation of eIF2·GTP, a rate-limiting step of translation initiation64,65 (Figure 3D). RNAi inactivation of eIF2Bδ decreased global protein synthesis.65 Four copies of eIF2Bδ were found in the YHSC genome, while at most two copies were found in the other genomes examined (Figure 3B). The eIF5A gene, previously considered a translation initiation factor, is implicated in the elongation step of protein synthesis and mediates the formation of the first peptide bond59,62 (Figure 3D). Indeed, the eIF5A protein can increase protein synthesis by 2- to 3-fold in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.59 We identified seven copies of eIF5A in the YHSC genome but at most two copies in any other genome examined (Figure 3C). Thus, the expansion of these genes in the translation initiation pathway may increase the synthesis of proteins and reduce protein synthesis inhibition under high pressure and low temperature.

Figure 3.

Adaptive changes in translation initiation factors and ribosomal proteins to combat protein synthesis inhibition induced by high pressure and low temperature in the hadal zone

(A–C) Phylogenetic trees showing the expansion of genes for the translation initiation factors eIF4G1, eIF2Bδ, and eIF5A in the YHSC genome.

(D) Model of the translation initiation pathways.57,58,59,60 Expanded genes are marked in red. (1) eIF2B promotes the exchange of GDP-GTP on eIF2, a rate-limiting step of translation initiation. Then, eIF2-GTP forms a ternary complex (eIF2-GTP-Met-tRNAiMet) together with initiator tRNA (Met-tRNAiMet). (2) The ternary complex was recruited to 40S subunits to form 43S complexes with other factors. (3) The eIF4F complex, consisting of eIF4E, eIF4A, and eIF4G1, bound to mRNA and mediated the unwinding of the mRNA cap-proximal region with the help of eIF4B, and mRNA was activated. (4) 43S complex attached to the activated mRNA and scans the 5′UTR of mRNA to the initiation codon - AUG. (5) eIF5B-mediated ribosomal subunits joining and displacement of translation initiation factors. (6) eEF1A carries aminoacyl-tRNA to the A site of the ribosome.61 (7) eIF5A mediated the formation of the first peptide bond.59,62

(E and F) Phylogenetic trees based on protein sequences containing domains of Ribosomal_S5 (E), and Ribosomal_L4 (F) show the expansion of RPS2 and MRPL4 genes in the YHSC genome.

(G) Alignment of the amino acid sequence of MRPS27. MRPS27 is a gene that experienced convergent positive selection between the YHSC and P. swirei. Amino acids unique to the YHSC or P. swirei are indicated by arrows.

Ribosomal proteins are the major components of ribosomes and function mainly by maintaining ribosome integrity or promoting protein synthesis. In this study, two ribosomal protein genes (RPS2 and MRPL4) underwent expansion, and three mitochondrial ribosomal protein genes (MRPS27, MRPS30, and MRPS35) were positively selected. RPS2, a component of the 40S subunit, mediates the binding of aminoacyl-transfer RNA to the ribosome,66 a process that is strongly inhibited by high hydrostatic pressure.53 The YHSC genome harbored 10 copies of the RPS2 gene, which far exceeded the number of copies in any other genome examined (maximum 2; Figure 3E). MRPL4 maintains the structural integrity of the ribosome and participates in mitochondrial protein translation.67 There were four copies of the MRPL4 in the YHSC genome but only one in each of the other genomes examined (Figure 3F). MRPS27, as a small subunit of mitochondrial ribosomes, is required for protein synthesis in mitochondria, and knockdown of MRPS27 lowered mitochondrial translation.68 Interestingly, the MRPS27 was subject to convergent positive selection in the hadal YHSC and P. swirei (Table S12), and many amino acids unique to the YHSC or P. swirei were identified (Figure 3G), which is suggestive of its important role in hadal adaptation. Thus, the expansion or positive selection of genes for these translation initiation factors and ribosomal proteins may ameliorate protein synthesis inhibition in the hadal zone by increasing protein synthesis, promoting the binding of aminoacyl-tRNA to ribosomes, or improving ribosomal stability.

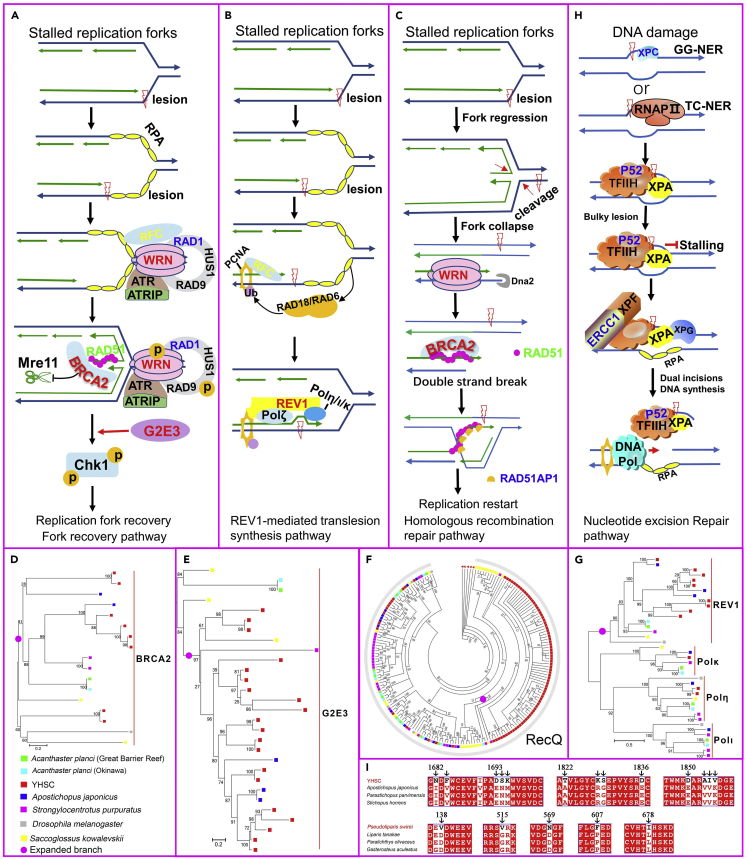

Yap hadal sea cucumbers exhibited enhanced DNA protection abilities for high-pressure adaptation

Replication forks frequently encounter obstacles, which often lead to fork stalling even under normal conditions.69,70 Two major strategies are used by cells to rescue stalled forks71: replication fork recovery, which involves fork protection, checkpoint activation, removal of replication impediments, and fork resumption69,72 (Figure 4A), and REV1-mediated translesion synthesis, which uses error-prone translesion-synthesis DNA polymerases to conduct the replication process74,82 (Figure 4B). When stalled replication forks collapse, producing one-ended double-strand DNA breaks, the collapsed forks are repaired using homologous recombination72 (Figure 4C). However, DNA synthesis can be interrupted by high hydrostatic pressure, and the resumption of stalled or collapsed replication forks is also a pressure-sensitive process.4,8,83 Here, we identified expansions in four genes associated with recovery of stalled replication forks in the YHSC genome, including Breast cancer type 2 (BRCA2), Werner syndrome protein (WRN), G2/M-phase-specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (G2E3) and REV1. BRCA2 functions in the fork recovery pathway and homologous recombination repair pathway by mediating the assembly of RAD51 onto ssDNA (forming RAD51 filaments) and stabilizing RAD51 filaments84,85,86 (Figures 4A and 4C). In the fork recovery pathway, the RAD51 filaments protect nascent DNA at stalled replication forks from MRE11-mediated nucleolytic degradation69,86,87,88 (Figure 4A). During homologous recombination repair, RAD51 filaments promote the invasion and exchange of homologous DNA with the help of RAD51-associated protein 1 (RAD51AP1)85,89,90 (Figure 4C). There were eight copies of BRCA2 in the YHSC genome but two at most in any other genome examined (Figure 4D). Furthermore, the RAD51AP1 was positively selected in the YHSC (Table S15). Interestingly, the genome of a hadal snailfish captured from Yap Trench has more copies of RAD51 than other teleost genomes analyzed,15 indicating that the enhanced formation of RAD51 filaments mediated by BRCA2 may be essential for hadal adaptation. G2E3, the expression of which is induced by DNA damage, participates in replication fork recovery by activating checkpoint kinase 1 (CHK1) kinase79,91,92 (Figure 4A). We identified 20 copies of G2E3 in the YHSC genome, compared with three at most in all other genomes examined (Figure 4E). WRN, a member of the RecQ family, is a checkpoint protein in the replication fork recovery and double-strand DNA break repair pathway with ATP-dependent 3′-5′ DNA helicase activity72,77,93 (Figures 4A and 4C). Far more copies of WRN were identified in the YHSC genome than in any other genome examined (Figure 4F). Finally, REV1, as a scaffold protein, mediates translesion synthesis by interacting with other translesion synthesis DNA polymerases and selecting the polymerases required for translesion synthesis75 (Figure 4B). In addition, REV1 also participates in translesion synthesis by employing its dCMP transferase activity, which inserts a dCMP opposite a lesion.94 The YHSC genome has 9 copies of REV1, at least four more than in any other genome examined (Figure 4G). The expansion of genes involved in rescuing stalled or damaged replication forks may provide a solution for DNA synthesis in the hadal zone.

Figure 4.

Enhanced DNA protection ability of the YHSC for hadal adaptation

Genes in red and blue underwent the expansion and positive selection in the YHSC, while genes in green and yellow refer to expanded and positively selected genes in P. swirei.

(A–C) Mechanisms for restoring stalled and collapsed replication forks.72,73 Upon encountering obstacles, the replication fork stalled, and the ssDNA is generated and covered by replication protein A (RPA) to avoid secondary structure formation. The stalled fork can be rescued through the fork recovery pathway by activating the downstream effector CHK172 (A) or REV1-mediated translesion synthesis74,75 (B). If the fork is not properly restarted, the replication fork collapses, one-ended double-strand breaks are induced76 and the fork is repaired by homologous recombination72 (C). (A) In the fork recovery pathway, the ssDNA-RPA complex recruits some proteins.72,77 Meanwhile, BRCA2 catalyzes the formation and stabilization of RAD51-ssDNA filaments, which protects nascent DNA from MRE11-mediated nucleolytic degradation.69,78 Then, CHK1 is activated with the help of G2E3,79 and the replication fork restarts after obstacle removal.69,71 (B) In the translesion synthesis pathway, RAD18 and RAD6 interact with the ssDNA-RPA complex and then ubiquitinate proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA).80 REV1, which possesses a high affinity for ubiquitinated PCNA, is recruited to lesions and mediates translesion synthesis by interacting with Polζ and one of the three Y-family polymerases (Polι, Polη, and Polκ), and selecting the polymerases required for translesion synthesis.75,81 (C) In the homologous recombination pathway, the RAD51 filament facilitates strand invasion and homologous recombination after binding with RAD51AP1.72

(D) Phylogeny based on proteins containing the BRCA2 repeat domain (BRCA2) showed expansion of BRCA2 in the YHSC genome.

(E) A gene tree of G2E3 constructed by Orthofinder (version 2.3.8).

(F) Phylogenetic tree based on protein sequences containing DEAD/DEAH box helicases (DEAD). RecQ family labeled with an arc was not further subdivided, as different members could not be distinguished from each other. Nevertheless, 49 genes from the YHSC were annotated as WRN, far more than those from other species.

(G) Phylogeny built with proteins containing the impB/mucB/samB family C-terminal domain (IMS_C) showing the expansion of the REV1 gene.

(H) Nucleotide excision repair pathway. In the presence of DNA lesions, XPC or RNA Pol II loads TFIIH onto DNA, which is promoted by XPA. Upon detection of a bulky lesion, XPF-ERCC1 and XPG make dual incisions.42

(I) Multiple sequence alignment of XPC. XPC underwent convergent positive selection in the hadal YHSC and P. swirei. Amino acids unique to the YHSC or P. swirei are indicated by arrows.

High hydrostatic pressure also leads to DNA damage.4,6,9 In the YHSC genome, another conspicuous change occurred in the genes in the nucleotide excision repair pathway (Figure 4H). Three genes at least were subjected to positive selection in this pathway: XPC, TFIIH basal transcription factor complex p52 subunit (p52), and excision repair cross-complementation Group 1 (ERCC1). XPC recognizes sites of DNA damage and initiates nucleotide excision repair (NER)42,95 (Figure 4H). In this study, the XPC experienced convergent positive selection in the hadal YHSC and P. swirei (Table S12), and many YHSC- or P. swirei-specific amino acid substitutions were found (Figure 4I), which is suggestive of its important role in hadal adaptation. p52 and ercc1 promote the unwinding of DNA around a lesion and excise lesion-containing DNA fragments (Figure 4H). Thus, the expansion and positive selection of genes in replication fork recovery and the nucleotide excision repair pathway may protect DNA from damage exerted by the high pressure in the hadal zone.

Limitations of the study

In this study, we have tried to collect as many echinoderm genomes as possible for comparative analyses. However, only quite a few genomes are available at present. Such, our analyses are limited to the available genomic data, and this situation may be improved accompanying the increased publication of echinoderm genomes.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Biological samples | ||

| Paelopatides sp. Yap | This manuscript | D149; D150; D152 |

| Apostichopus japonicus | This manuscript | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| TRIzol | Invitrogen | Cat#15596026 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| QIAamp DNA Mini Kit | Qiagen | Cat#51306 |

| NEB Next® Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit | NEB | Cat#E7370L |

| SMRTbell Template Prep Kit 1.0 | Pacific Biosciences | Cat#100-259-100 |

| NEBNext Ultra RNA | NEB | Cat#E7770 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Raw sequence data of Paelopatides sp. Yap | This manuscript | GSA: CRA003479 |

| Assembled genome and annotation file of Paelopatides sp. Yap | This manuscript | Mendeley Data: https://doi.org/10.17632/6gn4kf77zm.1 |

| Apostichopus japonicus reference genome | Zhang et al.33 | http://www.genedatabase.cn/DownLoad_Haishen_20161129.html |

| Strongylocentrotus purpuratus reference genome | Ensembl | http://ftp.ensemblgenomes.org/pub/release-47/metazoa/fasta/strongylocentrotus_purpuratus/ |

| Acanthaster planci (Okinawa, Japan) reference genome | Hall et al.36 | https://marinegenomics.oist.jp/cots/viewer/download?project_id=46 |

| Acanthaster planci (the Great Barrier Reef, Australia) reference genome | Hall et al.36 | https://marinegenomics.oist.jp/cots/viewer/download?project_id=46 |

| Saccoglossus kowalevskii reference genome | NCBI | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/?term=Saccoglossus+kowalevskii |

| Drosophila melanogaster reference genome | Flybase | http://ftp.flybase.net/genomes/Drosophila_melanogaster/dmel_r6.34_FB2020_03/fasta/ |

| Genome and annotation file of Pseudoliparis swirei | Wang et al.16 | https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Genome_assembly_of_Mariana_hadal_snailfish/9782414 |

| Genome and annotation file of Liparis tanakae | Wang et al.16 | https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Genome_assembly_of_Mariana_hadal_snailfish/9782414 |

| Genome and annotation file of Paralichthys olivaceus | NCBI | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/?term=txid8255[orgn] |

| Genome and annotation file of Gasterosteus aculeatus | Ensemble | http://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/release-104/fasta/gasterosteus_aculeatus/ |

| Holothuria leucospilota | NCBI | DRR023763 |

| Parastichopus californicus | NCBI | SRR1695477 |

| Stichopus chloronotus | NCBI | SRR2846098 |

| Synallactes chuni | NCBI | SRR2895367 |

| Parastichopus parvimensis | NCBI | SRR2484238 |

| Stichopus horrens | NCBI | SRR11535195 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| diamond (version 2.0.14) | Buchfink et al.96 | https://github.com/bbuchfink/diamond |

| trimmomatic (version 0.36) | Bolger et al.97 | https://anaconda.org/bioconda/trimmomatic |

| GenomeScope (version 1.0) | Vurture et al.98 | http://qb.cshl.edu/genomescope/ |

| Generic Mapping Tools (version 6.0) | Wessel and Smith99 | https://www.generic-mapping-tools.org/download/ |

| Khaper | Zhang et al.100 | https://github.com/lardo/khaper |

| Canu (version 1.7) | Koren et al.101 | https://anaconda.org/bioconda/canu/files?sort=length&version=1.7&sort_order=asc&page=0 |

| GETA (version 1.0) | Li et al.102 | https://github.com/chenlianfu/geta |

| wtdbg2 (version 1.0) | Ruan and Li103 | https://github.com/ruanjue/wtdbg2 |

| bwa-mem (version 0.7.17) | Li104 | https://github.com/lh3/bwa |

| bwa-mem2 | Vasimuddin et al.105 | https://github.com/bwa-mem2/bwa-mem2 |

| Pilon (version 1.22) | Walker et al.106 | https://github.com/broadinstitute/pilon/releases/ |

| samtools (version 1.12) | Li et al.107 | https://github.com/samtools/samtools |

| eggno-emapper (version 0.12.7) | Huerta-Cepas et al.108 | https://github.com/eggnogdb/eggnog-mapper/releases?page=2 |

| Blast (version 2.6.0) | Camacho et al.109 | https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/executables/blast+/2.6.0/ |

| KASS (version 2.1) | Moriya et al.110 | https://www.genome.jp/kaas-bin/kaas_main |

| Phylosuite (version 1.2.1) | Zhang et al.111 | https://github.com/dongzhang0725/PhyloSuite/releases |

| mafft (version 7.453) | Katoh and Standley112 | https://github.com/bioinformatics-polito/LaRA2-mafft |

| mega (version 7.0) | Kumar et al.113 | https://www.megasoftware.net/ |

| wgd (version 1.1) | Zwaenepoel and Van de Peer31 | https://github.com/arzwa/wgd/releases |

| pfam (version 31.0) | Finn et al.114 | http://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/Pfam/releases/Pfam31.0/ |

| FastTree (2.1.11) | Price et al.115 | https://github.com/PavelTorgashov/FastTree |

| CAFE (version 4.2) | Bie et al.34 | https://github.com/hahnlab/CAFE/releases |

| OrthoFinder (version 2.3.8) | Emms and Kelly116 | https://bioweb.pasteur.fr/packages/pack@OrthoFinder@2.3.8 |

| PAML package (version 4.9) | dos Reis and Yang117 | https://anaconda.org/bioconda/paml |

| Trinity (version 2.1.1) | Grabherr et al.118 | https://github.com/trinityrnaseq/trinityrnaseq |

| Fastp (version 0.20.1) | Chen et al.119 | https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp |

| RSEM (version 1.3.1) | Li and Dewey120 | https://anaconda.org/bioconda/rsem/files?sort=ndownloads&sort_order=desc&version=1.3.1 |

| CD-HIT-EST (version 4.8.1) | Li and Godzik121 | https://github.com/weizhongli/cdhit/releases |

| BUSCO (version 5.3.0) | Simão et al.122 | https://github.com/WenchaoLin/BUSCO-Mod |

| Trans-Decoder (version 5.5.0) | Haas et al.123 | https://anaconda.org/bioconda/transdecoder/files |

| CallCodeml | Github | https://github.com/byemaxx/callCodeml |

| RepeatModeler (version 2.0.1) | Smit and Hubley124 | https://github.com/Dfam-consortium/RepeatModeler/blob/master/RepeatModeler |

| RepeatMasker (version 4.0.9) | Smit et al.125 | https://github.com/rmhubley/RepeatMasker |

| Tandem Repeats Finder (version 4.09) | Benson126 | https://tandem.bu.edu/trf/trf.download.html |

| GraphPad Prism (version 5.0) | GraphPad Software, San Diego | https://graphpad-prism.software.informer.com/5.0/ |

| Other | ||

| Codes, bioinformatic program commands, and key intermediate files | This manuscript | Dryad: https://doi.org/10.17632/6gn4kf77zm.1 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Xinhua Chen (chenxinhua@tio.org.cn).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Experimental model and subject details

This study does not include experiments or subjects.

Method details

Sample collection

The YHSCs were captured in the Yap Trench on 5 June 2017 at 8°3′19’’N, 137°33′6’’E (5,090 m; no. D149), on 9 June 2017 at 8°3′5"N, 137°35′43"E (6,429 m; no. D150), and on 13 June 2017 at 8°1′22"N; 137°50′41"E (6,633 m; no. D152) using the Jiaolong Manned Submarine (Figure 1A and Table S1). Samples were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and transported to our laboratory at Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, Fujian Province, China. The whole body of each individual was grinded to mix all the tissues together in liquid nitrogen. The tissue homogenate was used for subsequence molecular work. The topographic base map showing the collection sites in the Yap Trench was drawn using Generic Mapping Tools (version 6.0)99 based on ETOPO1 bathymetric data.130 We purchased live A. japonicus in Qingdao city, Shandong Province, China, in April 2020. The Paelopatides sp. 1 and Paelopatides sp. 2 were respectively collected on 8 August 2006 in North Pacific (34°39′00"N, 123°5′00"W, 4100 m) and on 4 September 2012 in Gulf of California (26°21′18"N, 110°44′45.6"W, 2733 m).24

Sequencing and assembly of the YHSC genome

In this study, the genomic DNA of YHSC no. D152 was sequenced using both single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing with the Pacific Bioscience (PacBio) Sequel platform and Illumina sequencing with an Illumina X Ten instrument. For Illumina sequencing, genomic DNA was first extracted using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). Genomic DNA purity and quality were checked using a Nano Photometer Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, respectively. Second, DNA fragmentation was performed using an ultrasonic processor. Each insert fragment was approximately 350 bp long. Terminal repair, base A addition, sequence adapter addition, purification, and PCR amplification were performed to prepare a 350-bp library according to the NEB Next® Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit (NEB, USA). After preliminary quantification using Qubit 2.0 (Invitrogen), the library concentration was diluted to 1 ng/μL. Library insert size was verified using an Agilent 2100 (Agilent Technologies), and Q-PCR was performed to ensure that the library concentration was sufficient for sequencing. Then the library was sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq X Ten. Adapter and low-quality reads were filtered by trimmomatic (version 0.36)97 with parameters “TruSeq3-PE.fa:2:30:10 LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 MINLEN:51”. The clean reads were used for estimation of genome size, repeat content and heterozygosity rate by using GenomeScope (version 1.0) with k-mer = 21.98

For PacBio sequencing, genomic DNA was firstly extracted by using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QiaGen) and assessed by using an Agilent 4200 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies) and agarose gel electrophoresis. Then G-Tubes (Covaris) and AMPure PB magnetic beads were respectively used to shear 8 μg of extracted DNA and concentrate the DNA fragments. SMRTbell libraries were constructed using SMRTbell Template Prep Kit 1.0 (Pacific Biosciences). The BluePippin system was used to select molecules ≥10 kb in the constructed libraries (Pacific Biosciences). The SMRTbell libraries were sequenced using a Pacific Bioscience Sequel platform. The raw data were cleaned by removing adaptor sequences, polymerase reads with length ≤50 bp, and reads with quality scores ≤0.8. Canu (version 1.7)101 was used to correct errors in the subreads. Considering the high heterozygosity rate of YHSC genome, wtdbg2 (version 1.0), which did not produce obvious artifactual duplications,103,131 was used to assemble the subreads into contigs. Then bwa-mem (version 0.7.17)104 algorithm was used to map the Illumina clean reads against the contigs, and variants that were considered as sequencing errors were polished using Pilon (version 1.22)106 with default parameters. Finally, the quality of the assembly was evaluated by mapping the Illumina reads to the polished contigs by bwa-mem2.105 The mapping rate (Mapped reads divided by total reads) was computed by samtools (version 1.12).107 We also evaluated genome integrity by BUSCO (version 5.3.0) with eukaryota_odb10 database.

Elimination of bacterial contamination and redundancy in YHSC genome

The exclusion of bacterial contamination started with the identification of contigs containing bacterial proteins. First, the non-redundant bacterial and deuterostome proteins were retrieved from the NCBI nr database. Then diamond (version 2.0.14)96 was used to query each of YHSC proteins against the bacterial and deuterostome proteins with an E-value threshold of 1e-5. Taxonomy assignment for each query sequence was based on the best hits. Exactly, in each best match, the query sequence was assigned to bacteria if the corresponding subject was bacterial, while assigned to YHSC if the subject was from deuterostome proteins. The contigs with ≥50% bacterial proteins or no deuterostome proteins were considered as bacterial sequences and were excluded. Khaper100 was employed to identify and remove redundant sequences from YHSC genome based on the 209.1 Gb Illumina clean reads with k-mer = 17.

Transcriptome sequencing

The methods of transcriptome sequencing were as follows. Total RNA was extracted from the YHSC using TRIzol (Invitrogen). mRNA was purified from the total RNA using poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads. Sequencing libraries were generated using NEBNext Ultra RNA (NEB). Briefly, first strand cDNA was synthesized using a random hexamer primer and RNase H. Second strand cDNA synthesis was subsequently performed using buffer, dNTPs, DNA polymerase I and RNase H. The terminal repair, addition of A-tailing and adapter were implemented according to the manual. The libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000, and 150 bp paired-end reads were generated. The raw data were cleaned by excluding adaptor sequences and low-quality reads by using Trimmomatic (version 0.36) with parameters “TruSeq3-PE.fa:2:30:10 LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 MINLEN:51”.

Genome annotation

Coding genes in the YHSC genome were predicted by using GETA (version 1.0) pipeline (https://github.com/chenlianfu/geta), which incorporates homology-based predictions, ab initio gene predictions, and transcript evidence according to previous reports.102,132 Exactly, we first built a customized library of repetitive sequences in this genome by RepeatModeler program (version 2.1). This library was further subject to RepeatMasker (version 4.0.7) program to predict a full set of repetitive sequences and also generated a repeat-masked genome with repetitive sequences replaced with Ns. Then RNA-seq reads were trimmed and cleaned using Trimomatic program and aligned against the genome by HiSat2 (version 2.1.0)133 with default parameters. Transcripts were extracted based on the BAM alignments by the sam2transfrag program implanted in the GETA pipeline. And ORFs were predicted by Trans-Decoder (https://github.com/TransDecoder/TransDecoder). We next applied the AUGUSTUS (version 3.2.2) program134 to iteratively train gene models using the high-quality transcripts aforementioned. In addition, the homology-based annotation was performed based on the alignment of homolgous proteins from A. japonicus, S. purpuratus, A. planci, S. kowalevskii, Helobdella robusta, and branchiostoma floridae to YHSC genome using TBLASTN in NCBI-Blast+ (version 2.6.0),109 followed by prediction of exact gene structures by using Gene-Wise (version 2.4.1)135 based on the blast hits. The final gene set was incorporated by paraCombineGeneModels program in the GETA pipeline. The settings for those tools refer to the “conf_for_big_genome.txt” file, at “https://github.com/chenlianfu/geta/blob/master/conf_for_big_genome.txt”. The functions of putative protein-coding genes were annotated by using eggno-emapper (version 0.12.7),108 which integrates information from both precomputed orthologous groups and phylogenies in the eggnog database,108 and also annotated by diamond (version 2.6.0) against the nr database. The KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (KASS) (version 2.1)110 was used to identify pathway information.

Phylogenetic position of the YHSC

To determine the phylogenetic placement of the YHSC, the barcode regions of three nuclear genes (18S rRNA, 28S rRNA, and H3) and two mitochondrial genes (16S rRNA and COI) in the YHSC genome were used to query the NCBI nt database using BLASTn.136 Next, available 18S rRNA, 28S rRNA, H3, 16S rRNA, and COI sequences for extant Holothuroidea were downloaded from GenBank (Table S9). Multigene phylogenies of extant Holothuroidea, including the YHSC, were then reconstructed based on the three nuclear genes or the two mitochondrial genes using Phylosuite (version 1.2.1).111 In detail, the nucleotide sequences of each gene from all species were aligned using mafft (version 7.453).112 The aligned sequences of the three nuclear genes were concatenated using the “Concatenate Sequence” program in Phylosuite, as were those of the two mitochondrial genes. The best-fit partitioning schemes and models of evolution were selected based on the results of partitionFinder2137 in Phylosuite, and phylogenies were inferred using MrBayes138 in Phylosuite with default settings. Phylogenetic clusters were identified based on a recent revision of the extant Holothuroidea.24

The divergence between the YHSC and the seven species that are most closely related to the YHSC in the Paelopatides, Bathyplotes, and Apostichopus according to Figure 1B was calculated based on the COI barcode sequences using the model of Kimura 2-parameter distance (K2P)139 in mega (version 7.0)113 as previously reported.25 The COI barcodes of YHSC Paelopatides sp. 1, Paelopatides sp. 2, A. japonicus, Apostichopus californicus, Apostichopus parvimensis, Bathyplotes sp. 1, and Bathyplotes sp. 2 (GenBank accession numbers are given in Table S9) were first aligned by the muscle program in mega (version 7.0).113 Then, the aligned sequences were used to calculate genetic divergence between the YHSC and seven other species using K2P.139

Inference of whole genome duplications from ks distributions

Whole genome duplication in YHSC genome was inferred from the whole paranome Ks distributions for A. japonicus and YHSC together with the Ks distribution of their one-to-one orthologs by using wgd (version 1.1).31 Firstly, the Ks distributions of paralogous gene families and one-to-one orthologs were performed by “wgd dmd” and “wgd ksd” commands. The “bokeh serve & wgd viz -i -ks” commands were used to interactively visualize the Ks distributions of the paralogous gene families and the Ks distributions of one-to-one orthologs together.

Evolution of gene families in the YHSC

Although we attempted to collect genomic data for species closely related to the YHSC, a lack of appropriate data meant that we were limited to four echinoderm genomes: A. japonicus, S. purpuratus, and two geographically separated populations of A. planci (Okinawa, Japan and the Great Barrier Reef, Australia). We also included two additional invertebrate genomes: D. melanogaster and S. kowalevskii (sequence sources given in the key resources table).

Functional domains in the protein sequences from the seven genomes were annotated using pfam (version 31.0)114 with default parameters, which uses the HMM scanning method to classify gene families. We compared domain numbers across the species analyzed. We considered domains with z scores >1.96 and more than 5 members in the YHSC genome to be expanded ones, following Wang et al.16 To identify expanded genes in expanded domains, protein sequences with the same domain of interest were aligned using mafft (version 7.453),112 and the resulting alignment was used for phylogenetic tree construction by FastTree (2.1.11)115 with default parameters. Genes with a z scores >1.96 and no less than 4 copies in YHSC genome were regarded as expanded ones.

Additionally, CAFE (version 4.2)34,35,140 was used to evaluate the expansion and contraction of gene families in the YHSC genome compared with the other six genomes. CAFE infers the most likely the size of gene families at all internal nodes and identifies gene families with an accelerated rate of gain or loss using the size of gene families and an ultrametric tree as inputs.34 This analysis had four main steps. First, gene numbers in gene families across the seven genomes were calculated, and a species tree was constructed using OrthoFinder (version 2.3.8)116 with a “-m msa” parameter. Gene families with ≥200 members in any single species were excluded from further analysis.16 Second, an ultrametric tree was constructed using MCMCTree in the PAML package (version 4.9)117, and three soft calibration bounds were set based on timetree141: A. planci-A. japonicus: 450–605 Ma; S. purpuratus-S. kowalevskii: 535–763 Ma; and A. japonicus-D. melanogaster: 643–850 Ma. Third, CAFE (version 4.2)34,35 was used to identify gene families with accelerated rates of gain and loss. Gene families for which the p value of the YHSC branch was <0.01 were defined as significantly expanded or contracted, following a previous study.142 Fourth, the numbers of gene families that had undergone expansions or contractions were plotted on the phylogenetic tree following a previous study.34

Positive selection analysis

Due to the lack of genomic data of Holothuroidea, we attempted to include transcriptome data from this taxon in PSG identification in the YHSC genome. First, we conducted de novo assembly and functional annotation of the transcriptome from 6 species (as much as we could collect), including Holothuria leucospilota (NCBI Accession: DRR023763), Parastichopus californicus (SRR1695477), Stichopus chloronotus (SRR2846098), Synallactes chuni (SRR2895367), P. parvimensis (SRR2484238) and Stichopus horrens (SRR11535195) according to previous methods.9 Briefly, Fastp (version 0.20.1)119 was used to remove adaptors and low-quality reads. The clean reads were utilized for de novo assembly by Trinity (version 2.1.1).118 RSEM (version 1.3.1)120 was performed to quantify the transcripts, and only the isoform for a gene with the highest abundance was retained. CD-HIT-EST (version 4.8.1)121 was employed to remove transcripts with a similarity over 95%, and transcripts less than 200 bp were also excluded from further analysis. BUSCO (version 5.3.0, metazoa_odb10)122 was used to evaluate the completeness of the transcripts. Species with a complete BUSCO less than 90% were excluded, which means that only P. parvimensis and Stichopus horrens were used for further analysis (Table S16). Trans-Decoder (version 5.5.0)123 was used to predict coding regions by integrating the results of a BLAST search against the SWISS-PROT database and a Pfam search against the PFAM-A database into coding region selection.

Considering the completeness of the assembled transcripts, we selected transcripts from P. parvimensis, Stichopus horrens, YHSC and A. japonicus (Table S16) for PSG identification in the YHSC. Briefly, single-copy orthologs and phylogenetic relationships of the four species were inferred by OrthoFinder (version 2.3.8).116 The single-copy orthologs were aligned by ParaAT (version 2.0) with the “-g” and “-m mafft” options. CallCodeml (https://github.com/byemaxx/callCodeml), which calls Codeml143 to calculate positive selection in the site-branch model in bulk and to determine the p value with the chi-squared test, was used to calculate the selection pressure of the “foreground” phylogeny (YHSC branch). The p values were corrected by multiple testing correction.144 Genes with a corrected p value < 0.05 and with Bayesian empirical Bayes (BEB) sites >0.9 were considered PSGs. To study the convergent sequence evolution for hadal adaptation, we also calculated the selection pressure of P. swirei in the Mariana Trench using P. swirei as the foreground phylogeny and three closely related shallow-sea species according to a previous report,16 including P. olivaceus, G. aculeatus and Liparis tanakae, as the background phylogeny. The downloaded website of their genome and annotation file are shown in the key resources table. The methods were the same as those for PSG identification in the YHSC genome. The same gene that underwent positive selection in both of the two distantly related taxa was considered as convergent evolution, referring to previous reports.145,146,147

Identification of repeat elements in the YHSC genome

We compared the abundance of repeated elements in the YHSC genome with those in another four echinoderm genomes namely A. japonicus, S. purpuratus, A. planci (Okinawa), A. planci (Great Barrier Reef). De novo prediction was used to identify repeat elements in these genomes. First, a custom library of transposable elements was constructed for each species using the RepeatModeler pipeline (version 2.01).124 Repeats were then predicted based on the libraries using RepeatMasker (version 4.1.0).125 Tandem repeats were predicted using Tandem Repeats Finder (version 4.0.9).126

Fatty acid profiles in phospholipids

To explore adaptive changes in cell membrane components in response to increased hydrostatic pressure, various fatty acids (C6–C24) in phospholipids from the three YHSCs (D149, D150, and D152) and six A. japonicus were analyzed using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Due to sample deficiency, each individual was only measured once.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Significant differences in the relative abundance of each fatty acid between the YHSC and A. japonicus were identified by using a two-tailed t test as implemented in Microsoft Excel 2019. p values < 0.05 were considered significant. Graphical representations of the data were designed using GraphPad Prism 5.0. Data were presented as the means ± SEM. The threshold setting for the diamond program was E-value < 1e-5. The cutoff for expanded domains was z scores >1.96 and >5 members in the YHSC genome,16 while the cutoff for expanded genes was z scores >1.96 and ≥4 copies in YHSC genome. For PSG identification, genes with a corrected p value < 0.05 and Bayesian empirical Bayes (BEB) sites >0.9 were considered PSGs. The changes of gene families were inferred by cafe, the ones with p value of the YHSC branch <0.01 were defined as significantly expanded or contracted gene families, following the previous study.34

Additional resources

This study does not include additional resources.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Program on Key Basic Research Project (973 Program) (2015CB755903), China Agricultural Research System (CARS-47), China Ocean Mineral Resources R & D Association Program (DY135-B2-16), Fujian Science and Technology Department (2021N5008).

Author contributions

Chen, X.H and Zhang, L.S designed this study; Ao, J.Q., Ruan, L.W., and Wang, Y.G., collected the materials. He, T.L, Mu, Y.N., and Mu, PF performed the genome assembly and genome annotation. Gao, Y and Liu, D.G run the software of Orthofinder. The pfam domain in the genome used in the study was identified by Zhang, L.S. The Fatty acid profiles in phospholipids were determined by Lin, X.H. Shao, G.M wrote and revised the article, built all the evolutionary trees and drew all the figures.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing Interests.

Published: December 22, 2022

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.105545.

Contributor Information

Liangsheng Zhang, Email: fafuzhang@163.com.

Xinhua Chen, Email: chenxinhua@tio.org.cn.

Supplemental information

1-7TM, TOC, TN, 13Cδ, 15Nδ, C/N, and DO respectively refers to the temperature, total organic carbon, and total nitrogen.

Domains representing transposons were marked in red. Domains with z scores >1.96 and more than 5 members in the YHSC genome were considered as expanded ones.

Data and code availability

-

•

The raw sequence data generated in this paper were deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA)127 of the National Genomics Data Center,128 Beijing Institute of Genomics (China National Center for Bioinformation), Chinese Academy of Sciences, and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table. All genome sequence data and annotation files generated in this paper are available at Mendeley Data: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/6gn4kf77zm/1, and are publicly available as of the date of publication. The DOI is listed in the key resources table. Existing, publicly available data has been used in this study. Their accession numbers or websites have been listed in the key resources table.

-

•

Codes, bioinformatic program commands, and key intermediate files are available via Dryad: https://datadryad.org/stash/share/BATlLeHmrdDiWKzybITI1nATobLm30h8qXbM98yKE4o, and are publicly available as of the date of publication.129 DOI is listed in the key resources table.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- 1.Jamieson A.J. Cambridge University Press; 2015. The Hadal Zone: Life in the Deepest Oceans. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cossins A.R., MacDonald A.G. Homeoviscous theory under pressure: II. The molecular order of membranes from deep-sea fish. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1984;776:144–150. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(84)90260-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kato M., Hayashi R. Effects of high pressure on lipids and biomembranes for understanding high-pressure-induced biological phenomena. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1999;63:1321–1328. doi: 10.1271/bbb.63.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Follonier S., Panke S., Zinn M. Pressure to kill or pressure to boost: a review on the various effects and applications of hydrostatic pressure in bacterial biotechnology. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012;93:1805–1815. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3854-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwarz J.R., Landau J.V. Hydrostatic pressure effects on Escherichia coli: site of inhibition of protein synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 1972;109:945–948. doi: 10.1128/jb.109.2.945-948.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aertsen A., Michiels C.W. Mrr instigates the SOS response after high pressure stress in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;58:1381–1391. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dixon D.R., Pruski A.M., Dixon L.R.J. The effects of hydrostatic pressure change on DNA integrity in the hydrothermal-vent mussel Bathymodiolus azoricus: implications for future deep-sea mutagenicity studies. Mutat. Res. 2004;552:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yayanos A.A., Pollard E.C. A study of the effects of hydrostatic pressure on macromolecular synthesis in Escherichia coli. Biophys. J. 1969;9:1464–1482. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(69)86466-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lan Y., Sun J., Xu T., Chen C., Tian R., Qiu J.W., Qian P.Y. De novo transcriptome assembly and positive selection analysis of an individual deep-sea fish. BMC Genomics. 2018;19:394. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4720-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quinn P.J. Effects of temperature on cell membranes. Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 1988;42:237–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farewell A., Neidhardt F.C. Effect of temperature on in vivo protein synthetic capacity in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:4704–4710. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4704-4710.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martegani E., Alberghina L. Low-temperature restriction of the rate of protein synthesis in Neurospora crassa. Exp. Mycol. 1977;1:339–351. doi: 10.1016/S0147-5975(77)80009-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamieson A.J., Fujii T., Mayor D.J., Solan M., Priede I.G. Hadal trenches: the ecology of the deepest places on Earth. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010;25:190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolff T. The concept of the hadal or ultra-abyssal fauna. Deep Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts. 1970;17:983–1003. doi: 10.1016/0011-7471(70)90049-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mu Y., Bian C., Liu R., Wang Y., Shao G., Li J., Qiu Y., He T., Li W., Ao J., et al. Whole genome sequencing of a snailfish from the Yap Trench (∼7, 000 m) clarifies the molecular mechanisms underlying adaptation to the deep sea. PLoS Genet. 2021;17:e1009530. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang K., Shen Y., Yang Y., Gan X., Liu G., Hu K., Li Y., Gao Z., Zhu L., Yan G., et al. Morphology and genome of a snailfish from the Mariana Trench provide insights into deep-sea adaptation. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019;3:823–833. doi: 10.1038/s41559-019-0864-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu C., Li X., Wu Y. GAPPadder: a sensitive approach for closing gaps on draft genomes with short sequence reads. BMC Genomics. 2019;20:426. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5703-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu B., Shi Y., Yuan J., Hu X., Zhang H., Li N., Li Z., Chen Y., Mu D., Fan W. Estimation of genomic characteristics by analyzing k-mer frequency in de novo genome projects. arXiv. 2013 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1308.2012. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Berkum N.L., Lieberman-Aiden E., Williams L., Imakaev M., Gnirke A., Mirny L.A., Dekker J., Lander E.S. Hi-C: a method to study the three-dimensional architecture of genomes. J. Vis. Exp. 2010:1869. doi: 10.3791/1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koch L. Chicago HighRise for genome scaffolding. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016;17:194. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bocklandt S., Hastie A., Cao H. Bionano genome mapping: high-throughput, ultra-long molecule genome analysis system for precision genome assembly and haploid-resolved structural variation discovery. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019;1129:97–118. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-6037-4_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benjamin A.M., Nichols M., Burke T.W., Ginsburg G.S., Lucas J.E. Comparing reference-based RNA-Seq mapping methods for non-human primate data. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:570. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Y., Zhang Y., Wang A.Y., Gao M., Chong Z. Accurate long-read de novo assembly evaluation with Inspector. Genome Biol. 2021;22:312. doi: 10.1186/s13059-021-02527-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller A.K., Kerr A.M., Paulay G., Reich M., Wilson N.G., Carvajal J.I., Rouse G.W. Molecular phylogeny of extant Holothuroidea (echinodermata) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2017;111:110–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2017.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ward R.D., Holmes B.H., O'Hara T.D. DNA barcoding discriminates echinoderm species. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2008;8:1202–1211. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2008.02332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altis S. Origin and tectonic evolution of the Caroline Ridge and the Sorol Trough, western tropical Pacific, from admittance and a tectonic modeling analysis. Tectonophysics. 1999;313:271–292. doi: 10.1016/S0040-1951(99)00204-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujiwara T., Tamura C., Nishizawa A., Fujioka K., Kobayashi K., Iwabuchi Y. Morphology and tectonics of the Yap Trench. Mar. Geophys. Res. 2000;21:69–86. doi: 10.1023/A:1004781927661. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kobayashi K. Origin of the Palau and Yap trench-arc systems. Geophys. J. Int. 2004;157:1303–1315. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-246X.2003.02244.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee S.M. Deformation from the convergence of oceanic lithosphere into Yap trench and its implications for early-stage subduction. J. Geodyn. 2004;37:83–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jog.2003.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vanneste K., Van de Peer Y., Maere S. Inference of genome duplications from age distributions revisited. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:177–190. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zwaenepoel A., Van de Peer Y. wgd-simple command line tools for the analysis of ancient whole-genome duplications. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:2153–2155. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okumura S.I., Kimura K., Sakai M., Waragaya T., Furukawa S., Takahashi A., Yamamori K. Chromosome number and telomere sequence mapping of the Japanese sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus. Fish. Sci. 2009;75:249–251. doi: 10.1007/s12562-008-0025-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang X., Sun L., Yuan J., Sun Y., Gao Y., Zhang L., Li S., Dai H., Hamel J.F., Liu C., et al. The sea cucumber genome provides insights into morphological evolution and visceral regeneration. PLoS Biol. 2017;15:e2003790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2003790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Bie T., Cristianini N., Demuth J.P., Hahn M.W. CAFE: a computational tool for the study of gene family evolution. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1269–1271. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han M.V., Thomas G.W.C., Lugo-Martinez J., Hahn M.W. Estimating gene gain and loss rates in the presence of error in genome assembly and annotation using CAFE 3. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:1987–1997. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hall M.R., Kocot K.M., Baughman K.W., Fernandez-Valverde S.L., Gauthier M.E.A., Hatleberg W.L., Krishnan A., McDougall C., Motti C.A., Shoguchi E., et al. The crown-of-thorns starfish genome as a guide for biocontrol of this coral reef pest. Nature. 2017;544:231–234. doi: 10.1038/nature22033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liao X., Li M., Hu K., Wu F.X., Gao X., Wang J. A sensitive repeat identification framework based on short and long reads. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:e100. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmed M.Y., Al-Khayat A., Al-Murshedi F., Al-Futaisi A., Chioza B.A., Pedro Fernandez-Murray J., Self J.E., Salter C.G., Harlalka G.V., Rawlins L.E., et al. A mutation of EPT1 (SELENOI) underlies a new disorder of Kennedy pathway phospholipid biosynthesis. Brain. 2017;140:547–554. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loïodice I., Alves A., Rabut G., Van Overbeek M., Ellenberg J., Sibarita J.B., Doye V. The entire Nup107-160 complex, including three new members, is targeted as one entity to kinetochores in mitosis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:3333–3344. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e03-12-0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geng L., Wang S., Zhang F., Xiong K., Huang J., Zhao T., Shi D., Lv F., Li L., Liang D., et al. SNX17 (sorting nexin 17) mediates atrial fibrillation onset through endocytic trafficking of the Kv1.5 (potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily A member 5) channel. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2019;12:e007097. doi: 10.1161/circep.118.007097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Körner C., Knauer R., Stephani U., Marquardt T., Lehle L., von Figura K. Carbohydrate deficient glycoprotein syndrome type IV: deficiency of dolichyl-P-Man:Man(5)GlcNAc(2)-PP-dolichyl mannosyltransferase. EMBO J. 1999;18:6816–6822. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li C.L., Golebiowski F.M., Onishi Y., Samara N.L., Sugasawa K., Yang W. Tripartite DNA lesion recognition and verification by XPC, TFIIH, and XPA in nucleotide excision repair. Mol. Cell. 2015;59:1025–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oliver K.R., Greene W.K. Transposable elements: powerful facilitators of evolution. Bioessays. 2009;31:703–714. doi: 10.1002/bies.200800219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chong P.L., Cossins A.R., Weber G. A differential polarized phase fluorometric study of the effects of high hydrostatic pressure upon the fluidity of cellular membranes. Biochemistry. 1983;22:409–415. doi: 10.1021/bi00271a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kato M., Hayashi R., Tsuda T., Taniguchi K. High pressure-induced changes of biological membrane. Study on the membrane-bound Na(+)/K(+)-ATPase as a model system. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:110–118. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2002.02621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hashimoto M., Hossain S., Yamasaki H., Yazawa K., Masumura S. Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid on plasma membrane fluidity of aortic endothelial cells. Lipids. 1999;34:1297–1304. doi: 10.1007/s11745-999-0481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ferdinandusse S., Denis S., Mooijer P.A., Zhang Z., Reddy J.K., Spector A.A., Wanders R.J. Identification of the peroxisomal β-oxidation enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of docosahexaenoic acid. J. Lipid Res. 2001;42:1987–1995. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2275(20)31527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Veldhoven P.P. Biochemistry and genetics of inherited disorders of peroxisomal fatty acid metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2010;51:2863–2895. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R005959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fajardo V.A., McMeekin L., LeBlanc P.J. Influence of phospholipid species on membrane fluidity: a meta-analysis for a novel phospholipid fluidity index. J. Membr. Biol. 2011;244:97–103. doi: 10.1007/s00232-011-9401-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Horibata Y., Elpeleg O., Eran A., Hirabayashi Y., Savitzki D., Tal G., Mandel H., Sugimoto H. EPT1 (selenoprotein I) is critical for the neural development and maintenance of plasmalogen in humans. J. Lipid Res. 2018;59:1015–1026. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P081620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pope D.H., Berger L.R. Inhibition of metabolism by hydrostatic pressure: what limits microbial growth? Arch. Mikrobiol. 1973;93:367–370. doi: 10.1007/bf00427933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pavlovic M., Hörmann S., Vogel R.F., Ehrmann M.A. Transcriptional response reveals translation machinery as target for high pressure in Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis. Arch. Microbiol. 2005;184:11–17. doi: 10.1007/s00203-005-0021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwarz J.R., Landau J.V. Inhibition of cell-free protein synthesis by hydrostatic pressure. J. Bacteriol. 1972;112:1222–1227. doi: 10.1128/jb.112.3.1222-1227.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gross M., Lehle K., Jaenicke R., Nierhaus K.H. Pressure-induced dissociation of ribosomes and elongation cycle intermediates. Stabilizing conditions and identification of the most sensitive functional state. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993;218:463–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Infante A.A., Baierlein R. Pressure-induced dissociation of sedimenting ribosomes: effect on sedimentation patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1971;68:1780–1785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.8.1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schulz E., Lüdemann H.D., Jaenicke R. High pressure equilibrium studies on the dissociation-association of E. coli ribosomes. FEBS Lett. 1976;64:40–43. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(76)80243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jackson R.J., Hellen C.U.T., Pestova T.V. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:113–127. doi: 10.1038/nrm2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prévôt D., Darlix J.L., Ohlmann T. Conducting the initiation of protein synthesis: the role of eIF4G. Biol. Cell. 2003;95:141–156. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(03)00031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Henderson A., Hershey J.W. Eukaryotic translation initiation factor (eIF) 5A stimulates protein synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:6415–6419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008150108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sasikumar A.N., Perez W.B., Kinzy T.G. The many roles of the eukaryotic elongation factor 1 complex. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2012;3:543–555. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tzivelekidis T., Jank T., Pohl C., Schlosser A., Rospert S., Knudsen C.R., Rodnina M.V., Belyi Y., Aktories K. Aminoacyl-tRNA-charged eukaryotic elongation factor 1A is the bona fide substrate for Legionella pneumophila effector glucosyltransferases. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gregio A.P.B., Cano V.P.S., Avaca J.S., Valentini S.R., Zanelli C.F. eIF5A has a function in the elongation step of translation in yeast. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;380:785–790. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Costello J.L., Kershaw C.J., Castelli L.M., Talavera D., Rowe W., Sims P.F.G., Ashe M.P., Grant C.M., Hubbard S.J., Pavitt G.D. Dynamic changes in eIF4F-mRNA interactions revealed by global analyses of environmental stress responses. Genome Biol. 2017;18:201. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1338-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pavitt G.D. eIF2B, a mediator of general and gene-specific translational control. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2005;33:1487–1492. doi: 10.1042/bst20051487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tohyama D., Yamaguchi A., Yamashita T. Inhibition of a eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF2Bdelta/F11A3.2) during adulthood extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. FASEB J. 2008;22:4327–4337. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-112953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kowalczyk P., Woszczyński M., Ostrowski J. Increased expression of ribosomal protein S2 in liver tumors, posthepactomized livers, and proliferating hepatocytes in vitro. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2002;49:615–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Andiappan A.K., Wang D.Y., Anantharaman R., Parate P.N., Suri B.K., Low H.Q., Li Y., Zhao W., Castagnoli P., Liu J., Chew F.T. Genome-wide association study for atopy and allergic rhinitis in a Singapore Chinese population. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]