Abstract

Background:

Lactation support, defined here as the access to educational resources, supplies, mental health and psychosocial support, skilled lactation counseling, and peer support, has been identified as critical to optimal health outcomes for birthing parents and infants. People who give birth while incarcerated are likely to receive suboptimal lactation support. The purpose of this review is to explore the literature on lactation support for incarcerated people to identify existing programs and policies, gaps in lactation support and ways to address the gaps, and incarcerated people's perspectives on breastfeeding and lactation support.

Methods:

We conducted a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature to identify studies that addressed two main concepts: (1) breastfeeding and (2) incarcerated populations in the United States.

Results:

After meeting the eligibility criteria, 29 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis of the findings. Studies highlight the importance of supporting birthing people who want to provide milk to their infants in a way that is desired, psychologically safe, and structurally supported. Programs are needed to delay or prevent parent-infant separation after birth, provide education around breastfeeding misconceptions, and link to resources and ongoing support for both breastfeeding and milk expression. Implementation of breastfeeding programs may be most effectively undertaken with clear policies and dedicated leadership either internally or through community or health care partnerships.

Discussion:

This review highlights the policies and practices that hinder adequate lactation support for birthing parent-infant dyads who are incarcerated and describes feasible policies, education, and clinical support that can be used to improve care.

Keywords: lactation, breastfeeding, incarceration, correctional sites, policies and procedures, equity

Introduction

More than 55,000 pregnant people experience incarceration in the United States each year, representing 3–4% of women admitted to jail or prison facilities.1,2 Current data on births during incarceration in the United States come from a single large study of 6 jails, 22 state prisons, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons, which identified more than 1,000 births in 2016.1,2 There is an urgent need to ensure adequate resources, support, and research to meet the health and health care needs and protect the basic human rights of birthing parent-infant dyads affected by incarceration.3 This includes lactation support, defined here as the access to educational resources, supplies, mental health and psychosocial support, skilled lactation counseling, and peer support.

Because perinatal incarceration disproportionately affects women in racially marginalized groups, incarceration also contributes to racial disparities in lactation support and human milk feeding in these populations. The racial discrimination underpinning the “War on Drugs” in the United States has led to hyper-incarceration of Black, Indigenous, and Latina women; Black women were notably 1.7 times more likely to be incarcerated than white women in 2019 and Black, Hispanic, and other non-white women accounted for most women imprisoned in that year.4 Socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, people who use substances, and rural populations also experience disproportionately high rates of incarceration. Incarceration exacerbates existing perinatal health disparities. Specific lactation support needs during incarceration vary by individuals' circumstances, infant feeding preferences and goals, and the types of carceral facility. All people who give birth during any incarceration require lactation support after delivery.

However, the timeframe for reuniting birthing parents with their infants may differ significantly both within and between jail and prison facilities. Jail facilities house individuals detained before a trial or for short sentences, with a mean length of stay 28 days and median of only 48 hours.5 Prison incarcerations, in contrast, are often both longer and farther from supportive social and familial resources. Short incarcerations during the postpartum period may result in the need for resources to maintain lactation through temporary separation and to mitigate medical and mental health complications that arise due to temporary infant separation. Lactation support needs during longer periods of incarceration likely include compassionate decision support regarding whether and how to maintain lactation during incarceration, strategies to connect infants with either human milk from a parent or a donor, and consideration of reestablishment of lactation upon return to the community if desired.

Beginning in the weeks immediately following birth and extending through the first 2 years postpartum, consensus guidelines recommend supporting lactation and the provision of human milk for infant feeding.6 Adaptations of the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative and other models of lactation support have been proposed for people who are incarcerated during the postpartum period.7,8 These recommendations emphasize the establishment of immediate postpartum-newborn attachment and bonding, lactation and infant feeding with human milk before separation in the hospital, providing resources for milk expression, and identifying mechanisms to connect infants with human milk after hospital discharge and separation of the dyad.

It is important to document the policy and practice environment that circumscribe lactation support during incarceration as well as how infant feeding intentions and experiences factor into lactation outcomes among people who are incarcerated. To this end, we conducted a systematic review of the literature to address the following key questions:

-

(1)

What are the perspectives of women who are incarcerated regarding breastfeeding and lactation support?

-

(2)

How do hospitals, clinicians, prisons, and jails support, encourage, or enable “successful” lactation and use of human milk for incarcerated women?

-

(3)

What are some ways that the current gaps in lactation support for incarcerated women can be filled?

Methods

Search strategy

A trained clinical health sciences librarian (S.T.W.) performed our comprehensive electronic search of publications using the following databases: PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature via EBSCO, EMBASE via Elsevier, and Scopus. Our search was not restricted by language. All database results were collected from the inception of the database through March 11, 2022. Search terms were used to retrieve articles addressing the two main concepts of the search strategy: (1) breastfeeding and (2) incarcerated population. The exact search strategy used in each of the electronic databases is reported in Appendix A1. We also manually searched the reference lists from selected articles to ensure comprehensive review of the literature.

The search strategy was conducted in PubMed using keyword and MeSH combinations; the other databases used a combination of text words and controlled vocabulary, if applicable. Results were downloaded to EndNote and duplicates were removed. All references were uploaded to Covidence Systematic Review software, a web-based tool designed to facilitate and track each step of the abstraction and review process.

Study selection

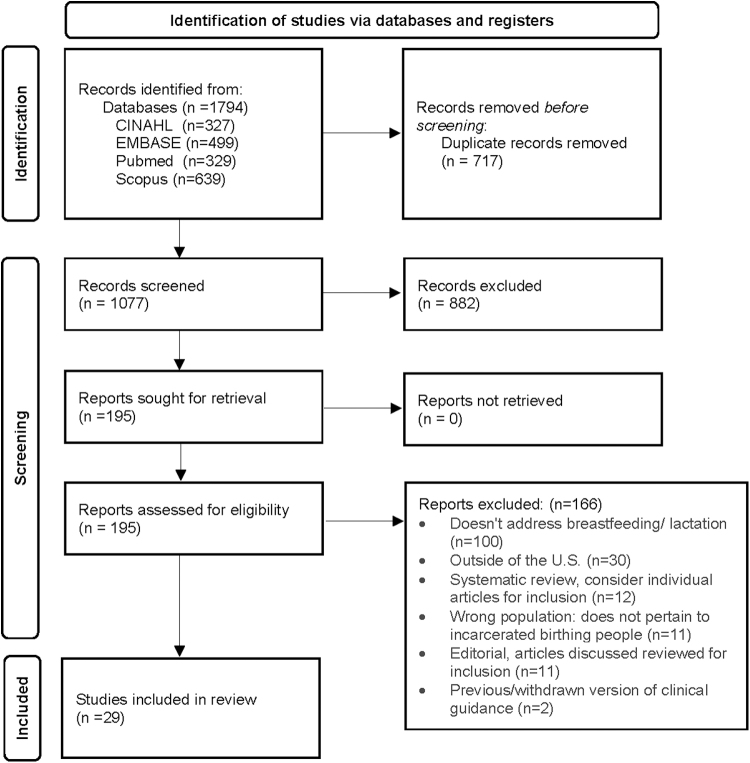

One investigator (K.W.) screened all study titles and abstracts and included articles where they met the following criteria: (1) the population described comprises people who experience any type of incarceration at any stage of lactation and (2) the population described is based in the United States. A second investigator (A.K.) worked with the primary reviewer to resolve any uncertainty. Next, two investigators (K.W. and J.P.) screened all studies included in the full-text review. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram in Figure 1 illustrates the number of studies excluded at each stage of screening.

FIG. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. From: Page et al.39

Data extraction

One investigator (K.W.) extracted data from each article meeting inclusion criteria. Data were extracted on the study objectives, study type, methods, and relevant findings aligned with each of our three review objectives.

Language

When specific studies use the terms “women,” “mother,” and “maternal,” they are used in this review to describe those findings. Gender-inclusive language is used otherwise to affirm that individuals capable of lactation, breast/chestfeeding, and giving birth do not all identify as women or mothers.

Results

The database searches yielded a total of 1,794 results. After the deduplication process removed 717 citations, 1,077 were screened during the title/abstract phase. This process yielded 193 articles to be reviewed in the full text phase. A total of 164 articles were excluded, with reasons for exclusion noted on the PRISMA Flow diagram (Fig. 1). The most common reason for exclusion at the full-text review stage was not addressing breastfeeding or lactation (n = 98). After meeting the eligibility criteria, 29 studies (including 1 article retrieved from the citations of an included study) were included in the qualitative synthesis of findings presented below.

The included articles were published between 1995 and 2022. Three articles were clinical position statements or briefs9–11; 13 case studies (of which 3 were conference presentations and one a Grand Rounds discussion)12–24; 2 combined cross-sectional baseline survey data with a cohort analysis of surveillance data25,26; 2 exploratory qualitative studies27,28; 2 program evaluations8,29; 2 ethnographic studies30,31; 1 cross-sectional case–control study32; 1 quality improvement study33; 1 retrospective cohort study34; 1 cross-sectional survey35; and 1 feasibility study (Table 1).36

Table 1.

Study Characteristics and Findings

| Authors (year of publication) | Study objectives | Article/study type | Study sample | Methods | Results: perspectives of incarcerated women; how hospitals, clinicians, prisons, and jails support lactation; and ways the current gaps in lactation support can be filled |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women (2021) | To describe recommendations for reproductive health care for incarcerated pregnant, postpartum, and nonpregnant individuals | Clinical position statement of ACOG | Relevant to all U.S.-based incarcerated populations | Recommendations for facilitating quality, dignified care for incarcerated pregnant, postpartum, and nonpregnant individuals at the local, state, and national levels. | (1) Work inside prisons, jails, and detention centers to provide medical care; (2) create/participate in systems that improve continuity of care after release; (3) advise facilities on guidelines and protocols to ensure comprehensive care, with breastfeeding promotion and support; (4) advocate at organizational, hospital, and local, state, and federal levels to ensure policies and laws follow clinical guidelines and protocols; eliminate copays to access health care in custody; restrict shackling; support policies/laws that decrease the number of incarcerated people; and promote community-based alternatives; (5) give appropriate compassionate care when incarcerated patients are treated at clinics and hospitals in community. Give birthing people same opportunities to bond with newborns; (6) advocate for data collection on reproductive health. |

| Allen and Baker (2013) | To describe a case of “supporting mothering through breastfeeding for incarcerated women” | Case study presented as a conference poster | One breastfeeding person incarcerated in a jail | Case study description. | The incarcerated person desired to breastfeed. After birth, health care team, mother, father, and guards created a breastfeeding and pumping plan. Newborn was discharged with father who picked up expressed milk daily from jail. Jail allowed mother to express in her cell and store milk in the medical unit refrigerator. At 10 days of age, newborn was exclusively fed expressed milk. |

| Asiodu et al (2021) | To assess the existence of prison and jail policies and practices that allow incarcerated women to breastfeed while in custody, and the prevalence of women in custody who express milk for their infants | Cross-sectional baseline survey analysis and cohort analysis of surveillance data on a subset of sites | Baseline survey data are from 22 state prison systems and 6 county jails from 2016 to 2017; 6 months of monthly surveillance data on the number of women expressing milk and the placement of infants born to women in custody from a subset of 13 prisons and 5 jails | Study sites completed a baseline survey describing (1) any lactation policy, with an open-ended question asking for detailed protocols; (2) any program for newborns to reside with mothers; (3) any other program for perinatal groups; and (4) if postpartum women could have contact visits where they could hold newborns in the first 3 months. For 6 months, a subset of 13 prisons and 5 jails completed an optional, supplemental, monthly reporting form on number of women who were lactating and placement information on infants born to women in custody. | Eleven prisons/five jails had policies to support milk expression or breastfeeding. Seven prisons/two jails had written lactation policies, and all policies supported breastfeeding, pumping, or both. Five prisons/two jails allowed women to pump for supply, but discarded milk. Two sites allowed pumping for supply only if close to release date. Some sites allowed pumping in living quarters; three sites allowed pumping in medical unit. Nineteen prisons/five jails had programs for pregnant and postpartum women, most commonly parenting classes. Twenty-one prisons/four jails permitted visits with infants in the first 3 months. One prison supported daily visits in the first 6 weeks, but only allowed pumping, not breastfeeding. Over 6 months at sites allowing lactation, 207 women gave birth in prisons and 8 per month expressed milk; at jails, 67 women gave birth and 6 per month expressed milk. Most infants placed in care of family member, with foster care second most common. 3 prisons had nursery: 19/95 infants placed in nurseries. 1 jail had nursery: 1/3 infants placed in nursery. Barriers and facilitators to implementing supportive breastfeeding policies and practices in the carceral system need to be better studied to guide more widespread adoption of lactation policies and programs and improvements to breastfeeding support. |

| Association of Women's Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN) (2018) | To describe the recommendations for nursing care of incarcerated women during pregnancy and the postpartum | Clinical position statement of AWHONN | Relevant to all U.S.-based incarcerated perinatal populations | Organizational position on perinatal care for incarcerated people, describe the role of the nurse, and review policy considerations. | Incarcerated women should receive same education and support as nonincarcerated populations, regardless of whether dyad will remain together after discharge. Options that allow birthing people to remain in the community are needed. Where not possible, carceral infrastructure should support dyad contact, including prison nurseries with developmental support, placement of parent in facility near family/infant caregivers, and visiting spaces for breastfeeding. Health care providers should develop action plans for breastfeeding, childcare, and housing for birthing people upon release; be familiar with relevant laws and institutional policies; work with incarcerated people, the care team, and the carceral officers to promote safe, quality perinatal care; advance policies that prohibit shackling. |

| Barkauskas et al (2002) | To determine if a community-based, residential program for incarcerated pregnant women with short-term sentences and histories of drug abuse improved maternal and infant health outcomes compared with traditional prison-based health care | Cross-sectional case–control study | Thirty-seven women who participated in the residential program were compared with 35 women with similar characteristics and eligibility for the residential program, but who remained in the prison | Health outcome data collected from the mothers' and infants' inpatient medical charts at a large university hospital and descriptive statistics are presented for each group. | Women selected for program remained through pregnancy and ≥4 months postpartum before discharged on parole. Participants supported by a family member or program volunteer at birth; returned to program with their infants to room-in until release. Offered on-site childcare. while attending educational and therapeutic sessions, employment enhancement services, and substance use education. Breastfeeding initiation: 19.4% in residential program group and 2.9% in comparison group. |

| Barrera et al (2018) | To describe how Alabama created partnerships to improve breastfeeding support and to report trends in maternity care practices and breastfeeding | Case study | Two individuals affiliated with the Alabama Department of Public Health and the ABC for interviews | Six interviews; two success stories developed by the CDC; eight final program reports reviewed for descriptive data. | Alabama State Perinatal Program worked with partners to develop a committee to increase breastfeeding in the state. ABC committee worked with Alabama Prison Project to provide pumps and other supplies during incarceration and to ship frozen milk to infant caregivers. Building state-level coalition of health care providers, educators, health department representatives, and individuals from different communities led to a nonprofit with strong executive board that works to improve breastfeeding support by leveraging partnerships, obtaining funding, and working with multisectoral partners to implement programs. |

| Bullock and Elson (2012) | To describe the work of The PBP at a regional women's jail | Case study | The PBP, a reproductive justice organization that works to provide support, education, and advocacy to women and girls at the intersection of the criminal justice system and motherhood | Descriptive data on PBP services. | PBP offers birth education, doula services, and peer groups; works with incarcerated people to change policies. Doulas support birthing people; advocate as needed; and teach advocacy skills to clients: Department of Corrections used to give mothers a small sports bra and suggest taking cold showers until milk stopped. Now they provide a pump: one mom expressed 5 times/day for 6 months, giving frozen milk to the baby's caregiver, and breastfed at weekly visits. Doulas educate hospital staff on breastfeeding on methadone. Offer peer support groups where mothers create birth, postpartum, safety, and relapse plans. Encourage dyad bonding; network with external groups for postrelease support. |

| Chambers (2009) | To examine the impact of separating incarcerated women from their babies after birth and during the postpartum period by exploring the nature and meaning of the mother-infant bonding experience in the context of forced separation | Exploratory qualitative study | Twelve incarcerated postpartum mothers from a southwest Texas prison hospital | Interviews conducted in early postpartum about mothers' prenatal and postpartum relationships with their babies. Constructivist inquiry provided the framework and qualitative methods. Data from audio recorded semistructured interviews were transcribed and comparative analysis occurred simultaneously with data collection to produce emergent themes. | Four themes to describe maternal-infant bonding in context of forced separation: “a love connection”; “everything was great until I birthed”; “feeling empty and missing a part of me”; and “I don't try to think too far in advance.” All spoke of a positive relationship with baby and plans to stay attached while separated and to reunite with and care for babies after release. Being separated from the infant at birth was shocking, and loss of the connection was painful. Separation was felt to be abrupt and indefinite. Realization that prenatal bonds might be lost created deep sadness and uncertainty. Giving birth was a transition from time of happiness to sadness. To cope, mothers looked at infant photos; prepared themselves by not dwelling on separation and believing it would be temporary. Mothers were not allowed to breastfeed, but 1 study participant reported breastfeeding before separation. Women in this prison birth in a university hospital connected to the prison hospital and are separated from their babies immediately after. Babies remain in the hospital nursery while mothers are returned to the prison hospital and not allowed to hold, breastfeed, bottle-feed, or care for their babies. Visits are allowed on days 2–3 postpartum when babies are released from the hospital to their caretakers. Nationally, legislation should reduce incarceration and increase community-based settings and provide a standard of health care for incarcerated women, which includes residential prison nurseries. At state level, efforts should note cost-savings of measures to end dyad separation. At the local level, nurses must assess the needs of incarcerated mothers, support coping mechanisms, and encourage and support breastfeeding and milk expression and storage, noting the cost savings of breastfeeding for the hospital, the prison system, and taxpayers. Nurses can implement special discharge planning policies to support family reunification using a team approach with lactation consultants involved. |

| Clarke and Adashi (2011) | To use a case study of a pregnant woman in jail as a springboard for discussion of the issues, benefits, and challenges of providing health care for incarcerated women | Case study presented during an Obstetrics and Gynecology Grand Rounds at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in 2010 | One incarcerated pregnant woman described in a case study; discussion relevant to care of incarcerated pregnant women in the United States | Case study description along with the view from the incarcerated pregnant woman and a question-and-answer section. | Participant described birth and infant feeding: “I had an officer with me the whole time that I was there [in the hospital]. I was trying to get away with not having an officer there. You know, it depends on where you stand in jail, if you're bad or you're good. But I was in between. So I had an officer there with me, and they didn't leave my side … They didn't let the baby in the room with me. I don't know why. The officers told me that with other ladies they had been in the hospital with, they had let the baby in the room. They had to call me every time she needed to be fed. In the hospital, they asked me if I wanted to breastfeed. And at first I wanted to. And then I was uncomfortable. There was an officer in the room every time I went to feed the baby. So it took away the urge that I had to breastfeed.” As a result of the incarcerated woman's methadone treatment for heroin use, the newborn required morphine- and phenobarbital-supplemented care over several weeks for NAS. Shortly after returning to jail, the mother and infant were released into a community-based residential treatment parenting program. Most pregnant incarcerated women are released before they give birth and need linkage to services in the community. Needs include medical care, shelter, food, safety, and substance use treatment. Prison diversion programs must be expanded to keep families together and to build the capacity of community drug treatment programs so jails are not used as substance abuse treatment facilities. Carceral officers follow policies set forth by institutions, which were historically male dominated and need to be adapted for women. |

| Drago et al (2022) | To examine whether maternal incarceration increases the length of hospitalization for infants with NAS. A secondary outcome looked at likelihood of breast milk feeding at discharge. | Retrospective cohort study | One hundred sixty-six infants with intrauterine opioid exposure born between 2011 and 2018 at the primary delivery site for Connecticut's women's prison: Yale New Haven's Lawrence and Memorial Hospital | Length of stay and breastfeeding at discharge were compared for infants with intrauterine opioid exposure born to incarcerated women versus those born to nonincarcerated women using Poisson regression. Bivariate comparisons were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum tests and Fisher's Exact tests or Chi-square tests. | Women transferred to the hospital for birth, room-in and attempt breastfeeding if desired. At 48–72 hours, women return to facility, where ability to visit or pump milk is limited by facility restrictions. Among 166 infants, 28 were born to incarcerated mothers and 138 born to nonincarcerated mothers. Ninety-three percent of incarcerated women were on methadone maintenance compared to 63% of nonincarcerated women. Infants of incarcerated women were significantly less likely to be fed breast milk at discharge, 3.6% versus 37% (p < 0.001), and had longer unadjusted length of stay (21.9 ± 15.0 days) versus infants born to nonincarcerated women (18.5 ± 11.1 days; p = 0.27). |

| Ferszt and Erickson-Owens (2008) | To describe the development of an education and psychosocial support group for pregnant women in a women's carceral facility | Case study | Nine pregnant incarcerated women and the medical and nursing staff at the carceral facility in the Northeast United States | Description of a pilot group developed and led by a social worker, a mental health clinical nurse specialist, and a nurse midwife for women at various stages of pregnancy and early postpartum. A needs assessment was conducted with medical and nursing staff at the facility and with the nine women pregnant in spring of 2005 to understand needs of the pregnant women. | Educational topics that were priorities for the incarcerated pregnant women who participated in the pilot sessions included infant feeding, bonding with one's baby, the postpartum period, and issues of loss and grief. A six-session, 1- and 1/2-hour, biweekly pilot group was developed to (1) improve physical and psychosocial well-being of pregnant, incarcerated women through education and support; (2) provide atmosphere comfortable discussing fears and asking questions of professionals; and (3) facilitate supportive peer network. Pilot sessions had introductions, a presentation on the topic of the day, and discussion. The group changed weekly, and the participants came with different concerns, so sessions adapted to be less structured, with a conversational style and education based on priorities of those present. The authors obtained funding and developed an educational booklet (edited with help from session participants) that is distributed to all pregnant women in the setting now. Address educational needs of nurses caring for pregnant women in the facility through new educational programs. Enlist volunteer doulas to support incarcerated birthing people. Providing groups for pregnant women in carceral facilities requires strong working relationships with professional and carceral staff. Establishing a formal linkage with professional staff, such as a parenting coordinator, supports the continuity of care. Strong relationships with nursing and medical staff help promote continuity of care. Nurses can assume a pivotal role in improving health care for pregnant incarcerated women by establishing education/support groups and working to improve policies and procedures in the carceral settings. |

| Ferszt et al (2013) | To provide information for carceral nurses related to the health care of pregnant women in prison | Case study | Health care providers working in a Northeastern U.S. state women's prison | Health care providers saw a lack of consistent care for pregnant women; quality improvement: reviewed pregnancy-related health care standards and aligned practices. Team presented information to the Warden to gain buy-in. | Improved care for pregnant incarcerated women: when a pregnant woman enters the prison, a blue dot is placed on her badge to let staff know she is pregnant. As part of prenatal care, a lactation consultant meets individually to discuss breastfeeding. If the woman wants to breastfeed and/or supply her milk to the newborn, carceral nurse works with medical and carceral staff to develop a plan to maintain security and the woman's autonomy, informed by guidelines for safe pumping, handling, and storing breast milk from the Office of Women's Health. Improved care requires collaboration with medical providers, social workers, the Warden, and other carceral staff. The identification of nursing care problems that arise in practice can guide nurses to interventions and advocacy for improving perinatal health in the carceral setting. |

| Grassley et al (2019) | To describe how staff from a health system and a carceral center collaborated to develop the infrastructure to provide supportive care to incarcerated childbearing women in their community | Case study | Staff from a health system and a carceral center in Idaho | Specific aims of this partnership included the following: (1) to establish a communication bridge between the prison health team and the health system nurses; (2) to identify and address expectations and responsibilities of security and hospital personnel when women were admitted to the hospital in labor; (3) to identify care gaps related to infrastructure; (4) and to align policies, operations, and delivery of care. The partnership started with a needs assessment to prioritize activities. | Perinatal nursing staff initially unsure about the carceral facility infrastructure and population needs (ability to room-in, breastfeed, and access to pump before discharge). Corrections staff lacked birth education. Each group offered workshops to the other. Resource binders made available on perinatal units, and a daily clinical report was shared between corrections security and health teams and health system staff. Health system staff gave free birth and parenting classes at the carceral center and invited infant caregivers. Support people allowed at birth. Nurses encourage rooming-in and mother's autonomy in newborn care. Help available from a lactation consultant; education on using a pump before discharge to establish and maintain a milk supply. Women are given access to unlimited infant visits at the carceral facility after discharge in a family-centric room with nursing pillows, a scale, diapers, toys, books, and rocking chairs. Women can breastfeed or give expressed milk. Carceral center owns two hospital-grade pumps and is developing a lactation support program; working with state health districts to provide health care for the infants and access to the WIC program. Staff are working with WIC to offer future access to breastfeeding peer counselors and child care classes that extend beyond the newborn period; they are developing a home visiting program for mothers after release from the carceral center. Nurses should review existing policies and processes from carceral facilities with whom they partner related to rooming-in and breastfeeding to see if they can be improved. Partnerships between health systems and carceral facilities are needed. A mother's support person should be welcome in the labor/delivery and mother/baby units. Nurses can offer mothers who are incarcerated opportunities to breastfeed in the hospital and to make a plan for milk expression. |

| Haney (2013) | To explore parenting inside the penal state, with a focus on the experience of care work done in prison and how motherhood was conceptualized and practiced in prison | Ethnography | Participants in a California mother/child prison that is part of the statewide Community Prisoner Mothers Program; the residential facility was located in a Bay Area city and run by “woman-centered” staff | Researcher participated in and observed lives of mothers and babies in Community Prisoner Mothers program for 3 years; attended house meetings, encounter groups, performances; taught classes; attended staff meetings and evaluations. | Some mothers claimed to fear connectedness of mothering, terrified by the idea that their kids would depend on them too much. “‘That whole breastfeeding thing just didn't work for me,’ … ‘I didn't want some little thing attached to my boob all the time, looking at me like a cow at every meal.’” Many mothers lacked parenting role models and felt nervous about their ability to caretake. Institutional practices of the prison conflated motherhood and punishment. Program focused on teaching mothers to bond with children. In weekly parenting class, focus on how mothers should put aside needs to hold and care for their children. Mothers had no privacy and were called on to bond with their kids in a way that expressed total dedication, even where women had ambivalent feelings about caretaking activities like breastfeeding. Prioritize alternatives to the penal state. There needs to be more dialog about how to draw partners/fathers into the parenting care work. Provide the support women need to parent outside of prison and to foster their social integration in the community. |

| Hotelling (2008) | To describe the importance of birth education and discuss different ways to support the needs of pregnant, incarcerated women | Case study | Relevant to all U.S.-based incarcerated perinatal populations | Describe model programs that provide physical and mental support for pregnant women in carceral custody. | Lamaze Certified Childbirth Educators assist pregnant, incarcerated women within some communities and provide educational skills about breastfeeding support. Many of these educators also provide birth and postpartum support as doulas. |

| Hromadka (1995) | To describe an innovative nursery program that allows incarcerated mothers to live with their babies until 18 months at the carceral facility | Case study | A nursery program, housed in the Nebraska Center for Women in York, Nebraska | Description of program services and characteristics. | Nursery program developed for mothers who give birth while incarcerated and accommodates ≤6 infants. Participants take prenatal courses; after birth, they care for infants, attend classes, and work part time at the facility. Community resources are used, like La Leche League. Program uses donated items to support the mothers, including bottles and formula, with a “Sponsor a Baby” program where individuals and community groups provide items for moms and babies after they leave the facility (i.e., high chairs, baby feeding utensils). |

| Huang et al (2012) | To examine the breastfeeding knowledge, beliefs, and experiences of pregnant women incarcerated in New York City jails | Exploratory qualitative study | Twenty women who were pregnant at the time of their incarceration selected to reflect the racial/ethnic composition of the population in The New York City Rikers Island Jail's Rose M. Singer Center, which houses female pretrial detainees and women sentenced up to 1 year | Semistructured interviews with questionnaire modifications were conducted and a grounded theory approach to data analysis was used to identify themes that explained incarcerated women's collective breastfeeding experiences. | Thirteen of twenty women planned to breastfeed; three more would have if not HIV positive. For those with prior breastfeeding experience, common challenges: difficulties latching, pain, concerns about breastfeeding in public, and separation from infants. Almost all reported receiving breastfeeding education from family/community. Women reported average breastfeeding knowledge, proficiency, and confidence. Confidence limited by concerns about separation. Some felt breastfeeding would make infants “too attached,” making separation and weaning difficult. Most spoke about wanting a new start in motherhood, seeing breastfeeding as part of maternal duties to support their sense of self-worth. Most wanted to learn about breastfeeding, pumping, and weaning; many had misconceptions about how illnesses and substances affect milk. Being in jail distanced them from a perceived negative lifestyle and social influences and allowed them to reflect on how addictions conflicted with caretaking. Breastfeeding affected by perceived ability to abstain from substances. Some mentioned jail-based resources and nursery program gave helpful information. Women valued breastfeeding for infant health. Some planned to protect infant by not breastfeeding, believing their use of substances, smoking, or poor health would produce harmful milk. Women with HIV wanted to protect their infants by not breastfeeding, but saw breastfeeding as a way to bond and grieved this loss. Some mentioned advantage of formula feeding due to separation. The Rose M. Singer Center includes a prenatal clinic and the only jail-based nursery program in the United States, where incarcerated pregnant women receive breastfeeding education and comprehensive health care services. Women are transferred to a nearby Baby-Friendly Hospital for delivery, where they are provided breastfeeding counseling and allowed to room-in with the infant. Postpartum incarcerated women who are enrolled in the jail's nursery program can reside with their infants for up to 1 year. They receive breastfeeding counseling and equipment, health and parenting education, and discharge planning. |

| Kim et al (2021) | To determine the number of pregnant people in JRS, their pregnancy outcomes, and health care needs | Cross-sectional baseline survey analysis and cohort analysis of surveillance data | JRS in three U.S. states | Monthly survey of 17 facilities in 3 states from April 2016 to January 2018; data aggregated by state. Baseline survey completed by designated reporter at each JRS (nurse manager, chief medical officer, or warden) noting pregnancy-related policies and if breastfeeding allowed. | Of the three JRS, two have a family physician, midwife, and a non-OBGYN physician on-site and refer to an outside OBGYN; one had an on-site OBGYN. All three allowed breastfeeding during visits with the newborns. Two JRS permitted mothers to express milk for pickup. In all three, pregnant adolescents were not furloughed or housed in a separate wing/unit. There were 71 pregnant admissions to the 3 sites during study period; 8 pregnancies ended in custody during the study period, with only 1 ending in a live birth (with 4 miscarriages and 3 induced abortions). Research is needed to understand what justice-involved pregnant youth need during and after incarceration, including (1) resources, (2) continuity of care outside the JRS, and (3) comprehensive mandatory reporting of pregnancy data at JRS across the United States. Trauma-informed breastfeeding education and services are needed, given the high prevalence of adverse childhood experiences, especially sexual abuse, in this population. |

| Knittel et al (2017) | To describe standards for evidence-based reproductive health care for incarcerated women | Brief drawing on case studies, program evaluations, and expert opinion | Relevant to all U.S.-based incarcerated populations | Synthesis of available studies and expert opinion to develop recommendations for providing reproductive health care to incarcerated women grounded in a human rights framework. | Most incarcerated women are separated from their infants after several hours to days postbirth, rely on family members to facilitate visits, and are limited to standard visiting hours to see infants. Few facilities offer breastfeeding resources. Residential programs, such as the MINT and WIAR, offer transitional housing outside the jail or prison for women to spend the last months of pregnancy and the first months postpartum with a high level of community support. Incarcerated women's health care needs should be met in a way that acknowledges circumstances, emphasizes dignity and autonomy; is gender responsive, informed by histories of trauma and sexual violence, roles as caregivers; addresses socioecological factors. Providers should be trained in trauma-informed care with oversight structures to evaluate whether needs of incarcerated women are being met and to address gaps. Incarcerated women should have access to prenatal care; programs to stay with infants; birth and parenting education and support, midwifery and doula care, supportive housing; pumps, time accommodations, milk storage and delivery to the infant, and lactation support; positions in medication-assisted treatment program and housing. |

| Mason (2013) | To describe how a PHVA assisted 1 incarcerated pregnant woman in navigating legal, social, and medical systems in support of bonding, attachment, healthy development, and positive parent-child interaction | Case study | PHVA services for one incarcerated woman at a county jail in New York where she was on methadone maintenance for previous heroin use | Case study description and macro perspective discussion | The incarcerated woman wanted to breastfeed. Family support workers in the PHVA met with pregnant woman biweekly at jail to help her bond with fetus, give health education, and address parenting concerns using a strength-based approach. PHVA discovered that state law allows incarcerated mothers to keep custody of children at the prison up to 18 months. Jail's social worker refused to have the jail house the infant; PHVA staff brought the pregnant woman a state prison nursery application and contacted a law firm for guidance; informed hospital that mother planned to breastfeed, but doctors were against this plan because of mother's methadone maintenance, and threatened to report her to CPS. PHVA staff found research to validate use of methadone while breastfeeding and got support from a pediatrician. The woman was transferred to another county jail; sister agency of the PHVA took up advocacy. After birth, baby was taken to the neonatal intensive care unit for methadone withdrawal, and mother was returned to jail and denied hospital visits. The mother expressed milk in her cell, and her stepmother picked it up daily and brought it to the hospital. Prison nursery denied the mother's application because her baby was not considered well by prison standards. Stepmother petitioned for guardianship and mother continued expressing milk for the baby daily. Baby was discharged from the hospital to the stepmother who resides 2 hours from the state prison. Despite New York State Corrections Law that allows new mothers to maintain custody of a child for up to 18 months, most facilities do not allow mothers to retain custody, citing the best interest of the child. Funding and space are needed to ensure facilities can implement this law and keep dyads together. The PHVA program is connected to community doulas who are willing to offer pro bono birth services for at-risk mothers; future collaborations with the jail system and the PHVA could connect incarcerated pregnant women to these doula supports for birth. PHVA staff is now establishing a more cooperative and collaborative relationship with staff at the county jail to ensure that future pregnant inmates receive support. Home visiting programs can offer support and education to both inmates and prison staff and can develop supportive relationships to improve outcomes for families affected by incarceration. |

| Seibenhener and McCormick (2019) | To describe the implementation of a program to introduce milk expression to women who give birth while incarcerated | Conference presentation of a case study | Seventeen women who gave birth while in a carceral facility after the implementation of breastfeeding support program | Case study description of a program to support incarcerated women to collect, store, and send their breast milk to their infant. | Collaboration between carceral facility and health care group led to acquisition of pumps, employee and inmate education, and access to lactation specialists. A licensed lactation counselor met weekly with participants. Of 17 births, 6 women chose to participate. 2 of the 6 were released 6 weeks after birth and reported planning to continue breastfeeding. One participant expressed her milk and had it delivered to the NICU, while infant hospitalized. |

| Meine (2018) | To improve equity of postpartum depression screening and treatment options for incarcerated pregnant and postpartum women | Quality improvement study that led to an unanticipated human milk expression program | Milwaukee County Jail and House of Corrections, large urban carceral facilities that house both short- and long-term low and maximum-security individuals | Rapid-cycle quality improvement project using four 2-week long Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles. | Unintended benefits of the project were incarcerated women stating relief that they were being screened for postpartum depression and expressing to their providers that they “felt listened to” more than they had at any other time in a carceral setting. Medical team of three physicians, six nurse practitioners, one nurse midwife, two psychiatrists, and three psychiatric nurse practitioners trained on screening using a shared decision-making tool, referral process through individual and group meetings, and group discussions. Of 101 women eligible for screening, 92% offered screening and 91% of those screened. Forty-three women with positive screens received a shared decision aid. Making this change to the initial booking questionnaire for incarcerated women led to four women starting a milk expression program. Need better engagement, trust building, and shared decision-making to improve services for incarcerated pregnant and postpartum people. |

| Paredes (2018) | To explore and improve care for incarcerated women and their newborns during labor, birth, and postpartum | Conference presentation of a case study | Recommendations from the literature and legislation informed this program for hospital care of incarcerated women and newborns | A collaborative group of interdisciplinary team members researched different aspects of perinatal care for incarcerated women. | Program goals: challenge use of shackles, promote dyad bonding, and introduce lactation-support options. Successful in stopping use of shackles during labor, facilitating dyad bonding with initiation of the “golden” hour and immediate skin-to-skin contact, and supporting breastfeeding with extended lactation support. Perinatal clinicians should feel empowered to challenge existing perinatal care practices for incarcerated women and advocate for implementing evidence-based standards that promote bonding and health outcomes. |

| Shlafer et al (2015) | To document the feasibility of a doula intervention for pregnant incarcerated women and to assess doulas' perceptions of ability to meet the goals of doula practice and provide substantive support to the women served | Feasibility study | Six doulas providing services to 18 pregnant women who delivered their infants during their incarceration in a state prison | Descriptive data on 6 doulas and 18 pregnant participants. Birth stories written by doulas coded through phenomenological approach to understand experiences supporting incarcerated women. | One of the mothers who breastfed her infant before separation noted that she was “terribly sad that the baby would have to switch to formula” and had breastfed the baby the whole time in the hospital “hardly putting her down at all.” Mother-infant separation at the hospital and after visits at the prison was emotionally harrowing for the mothers and the doulas supporting them. Case managers referred pregnant women to doula program on prison entry. All, but one participant had given birth before incarceration. Doula met with each woman at least twice before labor for prenatal education, birth planning, and emotional support. On average, doulas spent 8 hours with women at hospital; took pictures of the dyad during this time. Most women stayed in the hospital with baby for 48–72 hours. Doulas provided support during separation, when baby usually placed with a maternal grandmother and mother returned to prison. Doula met with women two more times postpartum; wrote narrative about birth, reflecting on their perceptions of the process. Doulas supported mothers who initiated breastfeeding. No support for mothers to express milk after separation, but doulas supported women who chose to initiate even though mothers would only spend a few hours with baby. One doula wrote, “Her baby was great learning to breastfeed. She latched on to her mother with no help, completely natural.” Doulas were successful in facilitating opportunities for bonding through breastfeeding. |

| Shlafer et al (2018) | To document breastfeeding intention and initiation among mothers in a prison-based pregnancy and parenting support program; test associations among breastfeeding intention, initiation, demographic and incarceration-related variables; identify themes from doula reports about supporting breastfeeding during the hospital stay | Mixed methods evaluation of a prospective cohort | A prison-based pregnancy and parenting program in one Midwestern U.S. state's only female prison | Thirty-nine pregnant women who received doula support surveyed on demographics, parenting, health, incarceration, and whether they intended to breastfeed. Program: weekly support group, one-on-one with doula six times. Doulas recorded meeting notes; wrote birth narrative. Survey data analyzed to test associations between variables. Qualitative data coded into themes on experience of supporting breastfeeding initiation. | Of the 39 women, 15 (45.5%) intended to breastfeed. After giving birth, 64.1% initiated breastfeeding. Neither breastfeeding intention nor initiation was associated with maternal age, race, education, number of children, sentence length, time already served, or time between birth and expected release. Given the short time mothers had to connect with their infants before separation, breastfeeding was important for establishing a mother-infant connection. 69.2% of women discussed breastfeeding with the doula in one-on-one meetings; discussing breastfeeding was significantly associated with breastfeeding initiation (p = 0.01). Women who discussed breastfeeding were seven times as likely to initiate as those who did not. Themes from doula narratives: breastfeeding benefits, barriers to breastfeeding, and role of the doula in supporting initiation. Doulas perceived several barriers: maternal and infant health, especially related to prenatal substance use; short time before separation, which led some mothers not to try or not to spend the limited time with baby working on breastfeeding; interactions with nurses who did not support them to breastfeed. Even where mothers did not plan to breastfeed, doula encouragement to try could help mothers be successful. Doulas provided breastfeeding support and assisted with positioning, latch, and cues. Short time between birth and release from custody highlights the importance of hospital and carceral policies to support breastfeeding. The prison revised its policies after the study period to allow women with <3 months remaining in their sentence to express and discard their milk to maintain a supply; institutional support is needed for milk storage and breastfeeding during visits. Adherence to BFHI and cultural competency training for health care providers could support incarcerated women to breastfeed. In 2017, a judge ruled that women incarcerated in New Mexico state prisons have the right to breastfeed and corrections policies banning breastfeeding violate state constitution; research should document changes after this ruling. Future research should also explore short- and long-term physiologic and mental health outcomes—and associated cost benefits—with breastfeeding. |

| Sufrin (2018) | To explore how women's reproduction is experienced and managed by carceral institutions, and how mass incarceration is itself a reproductive technology | Ethnography | Women's jail in San Francisco from 2012 to 2013, where the researcher practiced as an obstetrician gynecologist from 2007 to 2013. Over two-thirds of women at the jail were Black in a city where 6% of the residents were Black. The women whose narratives are presented were all women of color | Ethnographic research using a reproductive justice framework to examine how motherhood is promoted and foreclosed for incarcerated women. Researcher conducted participant observation among incarcerated women, jail guards, and health care staff in housing units, the jail's clinic, and other spaces through jail. | Kima was pregnant in jail after having two children in custody; gave birth and allowed a 2-day hospital stay to bond with baby before being returned to jail with baby placed in a foster home. CPS involved in deciding where baby would go; placed a police hold on the baby while in the hospital so Kima could not be with baby in her hospital room and could only breastfeed when escorted to the hospital's nursery handcuffed. This devastated Kima who “wailed for nearly an hour as the nurse removed her baby from her room.” Kima was grateful for postpartum visits with her baby where she felt she could access her maternal self through activities like breastfeeding. Kima tried to breastfeed and expressed milk in jail to maintain a supply, but the baby could not latch, so she used 2-hour visits to cuddle and feed formula. Jail where Kima was in custody allowed three newborn visits per week. Kima snuggled with her baby and tried to breastfeed under the watch of a guard. Jail had a protocol to allow mothers to express milk and store it in the clinic freezer, facilitating delivery to the baby's caregiver. The author describes a “heterobiological foundation of motherhood” for incarcerated women where having any relationship with the baby was conditional on state judgment of mother's worthiness. Jail where Kima was in custody did not have a prison nursery, which author notes is “actively designed to cultivate the culturally romanticized versions of motherhood, where devotion to one's baby, under the watchful carceral eyes, can be a woman's path to redemption. Putting aside the complexities of a child beginning its life in prison, these nursery programs are hypermaternal spaces that actively promote normative mothering.” Queer kinship and reproductive justice frameworks should be applied to future study of incarcerated women's reproduction. |

| Tomlin et al (2012) | To review the challenges to parenting while in prison and share examples of prison-based parenting programs | Case study | The Indiana Women's Prison WON Program. The Indiana Women's Prison is the oldest women's prison in the United States, and houses women at all security levels | Case study description. | WON Program allows new mothers to live on special unit with infants after birth: take breastfeeding classes, child development lessons, family therapy, and access Healthy Start services; leave the unit to attend GED, vocational or substance use treatment. Other incarcerated women who meet qualifying criteria serve as nannies, caring for babies when mother attends class or needs support. Babies are present during sessions with mothers; learn about how babies develop and are encouraged to notice their babies' skills and experiences. Systemic interventions should address parents' needs related to trauma, mental illness, and substance use and provide supports that address their post release needs for help with housing, jobs, and child care. Providers need training to provide consistent, evidence-based information and to monitor their own assumptions/biases. |

| Valdovinos et al (2021) | To examine successes and challenges of implementing gender responsive programming in a jail | Process evaluation of the implementation of gender responsive programming | The CRDF in LA County, the nation's largest women's jail | Data collected through site visits to jail: observation and interviews with staff; focus groups with pregnant incarcerated women; support staff surveyed. Reviewed agency strategic plans, policies, mission statements, practice and policy guidelines, intake, and case management processes, tracking tools, and services/programs. A Gender Responsive Policy and Practice Assessment tool used to gauge alignment with gender responsive principles. | Focus on staff development; program implementation was incremental and iterative. Main components: GRR, GRA, EBI, and CTU. GRA created to liaise between jail units and give information about rights, policy against shackling, and lactation program to express milk. Oriented women to jail programs and services; alternatives to incarceration identified if eligible. CTU formed external partnerships to support postrelease services; lactation program suggested by external partners and jail command staff were supportive because aligned with gender responsive model. Identified existing lactation programs to inform approach, developed policies for medical clearance, safe storage, and milk transfer. Staff said program: “instrumental in allowing the women to bond with their infants despite being in custody.” Doula program offers trained birth assistant. Executive support was essential to building gender responsive programs. The GRA position improves rapport and trust between pregnant incarcerated women and staff; jail is considering a two GRA model to improve coverage. A lack of a database and modern technological infrastructure made it difficult to track participants and tailor services. Partnerships with providers are needed to sustain external lines of funding and build coalitions of services. The CRDF and CTU noted their biggest mistake in implementing the GRR was building this as a program and not a system-wide sustainable change to policies and procedures. |

| Zust et al (2013) | To describe nurses' experiences caring for incarcerated patients during labor, delivery, and the acute postpartum period | Cross-sectional survey | Convenience sample of 11 (of 35) registered nurses staffing a perinatal acute health care unit that serves as the primary perinatal care provider for the state's only women's prison | Survey on caring for incarcerated obstetric patients with four statements on a Likert scale and four open-ended questions about challenges. | Nurses noted no lactation support before returning to prison, even if mother's release date is near. One nurse described working outside her institution to advocate for mothers to use a pump in prison: “We can give them a hand pump to keep their milk supply going. The problem is that the prison can't store the milk. Sometimes, I have volunteered to go over and get the milk, especially if the mom is going to be released in a week or 2.” Greatest challenge was separation and mother's anticipation of separation during labor. Two nurses empathized, noting the hospital allowed dyad bonding: “The baby and mom are never separated [in the hospital] unless mom makes that request,” and “Babies need to be with their moms as much as possible.” |

ABC, Alabama Breastfeeding Committee; ACOG, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; AWHONN, Association of Women's Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses; BFHI, Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CPS, Child Protective Services; CRDF, Century Regional Detention Facility; CTU, Community Transition Unit; EBI, Education-Based Incarceration program; GRA, Gender Responsive Advocate; GRR, Gender Responsive Rehabilitation Services Provider; JRS, juvenile residential systems; MINT, Mothers and Infants Nurturing Together; NAS, neonatal abstinence syndrome; NICU, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit; OBGYN, Obstetrician/Gynecologist; PBP, Prison Birth Project; PHVA, perinatal home visiting agency; WIAR, Women and Infants at Risk; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; WON, Wee Ones Nursery.

Key question 1: what are the perspectives of women who are incarcerated regarding breastfeeding and lactation support?

Eleven studies addressed incarcerated women's feelings about breastfeeding8,13,14,20,27,28,30,31,36 and/or the availability of lactation support.19,28,33 Primary themes identified in these studies were breastfeeding intentions, reasons not to breastfeed, the pain of separation of the parent-infant dyad after birth, and women's breastfeeding knowledge and desire for education to support lactation.

Breastfeeding intentions

Five studies described experiences of incarcerated women who wanted to breastfeed or express milk for their infants.8,13,14,28,31 One qualitative study reported findings from interviews with 20 pregnant women incarcerated in New York City jails. This cohort of women resided in one of the rare facilities that allows infants to stay with their mothers in a jail nursery for up to 1 year after birth.

Of the 20 women, 13 planned to breastfeed and an additional 3 would have decided to breastfeed if they were not HIV positive. These women spoke about seeking a new beginning in motherhood, and they saw breastfeeding as part of this plan, allowing them to carry out maternal duties and support their sense of self-worth. Women also reported feeling that their inability to use substances while in jail created a more safe and secure environment to initiate breastfeeding. Many of the study participants had jail sentences lasting <1 year in duration, facilitating the possibility of swift re-entrance into society and parenting roles outside the carceral system.28

Another study surveyed participants of a doula intervention for pregnant incarcerated women to assess breastfeeding intentions. Of the 39 women participating in this pregnancy and parenting program, 45.5% intended to breastfeed and 64.1% initiated breastfeeding.8 Many of these women were unable to meet their breastfeeding intention due to the inhospitable environment and lack of support. In another case study, a mother in jail described how she wanted to breastfeed, but was not permitted to try:

I had an officer with me the whole time that I was there [in the hospital]. I was trying to get away with not having an officer there. You know, it depends on where you stand in jail, if you're bad or you're good. But I was in between. So I had an officer there with me, and they didn't leave my side … They didn't let the baby in the room with me. I don't know why. The officers told me that with other ladies they had been in the hospital with, they had let the baby in the room. They had to call me every time she needed to be fed. In the hospital, they asked me if I wanted to breastfeed. And at first I wanted to. And then I was uncomfortable. There was an officer in the room every time I went to feed the baby. So it took away the urge that I had to breastfeed.13

Another case study described an incarcerated woman on methadone maintenance for previous heroin use, who wanted to breastfeed, but faced numerous barriers within the prison and hospital systems. This mother accessed support and advocacy from a perinatal home visiting agency (PHVA) to address barriers, such as being denied her legal right to maintain custody of the baby within the prison system and receiving incorrect medical advice to avoid breastfeeding while taking methadone. This mother expressed her milk for the baby daily, despite her infant being discharged from the hospital to a grandmother who resided 2 hours from the prison.14

Another ethnographic study described an incarcerated woman in a San Francisco jail who wanted to breastfeed and expressed gratitude for the opportunity to have visits with her baby where she felt she could access her “maternal self” through activities like breastfeeding. While this mother expressed milk in the jail to maintain her supply, the baby could not successfully latch on to breastfeed during visits, and the mother opted to instead use the time with her baby to cuddle and feed formula from a bottle. The author of this study used a reproductive justice framework to describe how mass incarceration both disrupts motherhood, while at the same time promoting an idealized normative motherhood unattainable during incarceration.31

Together, these studies highlight motivations to breastfeed during incarceration, including as expressions of maternal care and self-advocacy or self-worth. They also identify ways that incarceration disrupts breastfeeding through separation of dyads, logistical hurdles, stigma, and lack of support.

Reasons not to breastfeed

Two studies explored reasons why some incarcerated women did not plan to breastfeed.28,30 Some women were concerned about their substance use or poor health and perceived that these things might affect their milk quality. Breastfeeding intentions were affected by women's perceived ability to abstain from what they considered to be contraindicated substances, such as alcohol and tobacco, an unhealthy diet, or routine medications. Women living with HIV described a strong sense of needing to protect their infants from HIV infection. Some women noted that formula feeding would facilitate the ability of family members to feed the infant during separation.28

Some women expressed concerns that breastfeeding would encourage their infants to become “too attached” to them, making forced separation and the abrupt process of weaning more emotionally difficult.28 In an ethnographic study of participants in a mother-child prison in a Bay Area City, one participant expressed fear of the connectedness associated with mothering, the degree to which her infant would depend on her for feeding, and how this dynamic might change her relationship with her infant: “That whole breastfeeding thing just didn't work for me … I didn't want some little thing attached to my boob all the time, looking at me like a cow at every meal.”30

These reasons not to breastfeed explicitly identify perceived protection of the infant as an important factor in women's infant feeding decisions, including perceived protection from undue distress during separation and protection from potential exposures. They also suggest that social stigma and internalized stigma contribute to “mother blame” attitudes in which breastfeeding poses a risk to infants, which outweighs any perceived benefit. Together, these concerns highlight potential areas for prenatal education and postnatal lactation counseling.

Pain of postpartum-newborn separation

Dealing with the painful experience of coerced separation of mothers and infants after birth was a common theme in the literature.19,27,28,31,35,36 Most dyads affected by incarceration are separated after birth, with the infant being discharged from the hospital to a caretaker and the mother being returned to the carceral setting. A feasibility study of a doula intervention for pregnant incarcerated women described a mother who breastfed her infant in the hospital before separation.

This study noted how the mother reported feeling “terribly sad that the baby would have to switch to formula” and that she had breastfed the baby while in the hospital “hardly putting her down at all.” The process of mother-infant separation was an “emotionally harrowing experience” for mothers and the doulas supporting them.36 Another study that included qualitative interviews with 12 incarcerated mothers from a southwest Texas prison hospital found four themes in the context of forced mother-infant separation: (1) “a love connection,” (2) “everything was great until I birthed,” (3) “feeling empty and missing a part of me,” and (4) “I don't try to think too far in advance.”

These mothers were not allowed to breastfeed, but one participant reported having breastfed her infant before separation. The experience of forced separation from the infant and the loss of a love connection developed during the pregnancy were traumatic. Mothers described coping with this painful experience by looking at pictures of their infants and focusing on the separation as temporary.27 Another pilot study of an education and psychosocial support group developed for pregnant incarcerated women identified issues of loss and grief as participants' priorities for discussion.19

Ethnographic research from a women's jail in San Francisco described how one mother had never had the experience of going home from the hospital after birth with any of her three children. Child Protective Services (CPS) placed a police hold on the baby whose birth is described in this study, which meant the mother could not practice the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) standard of rooming-in with her newborn and could only breastfeed by being escorted to the hospital's nursery, while handcuffed. This unanticipated early separation devastated the mother, who “wailed for nearly an hour as the nurse removed her baby from her room.”

The mother was already guarded at all times, but this procedurally unnecessary hold was easy for the CPS worker to invoke given the mother's “reproduction as a black woman in the criminal legal system was already so policed, her maternal criminality already presumed.”31 Any effort to provide lactation support to people who have given birth while incarcerated will need to address the immediate and longer-term harms of separating these parent-infant dyads.

Breastfeeding knowledge and desire for education

Three studies explored incarcerated women's breastfeeding knowledge and priorities for desired education and support.19,28,33 In semistructured interviews with 20 incarcerated women at the New York City Rikers Island Jail's Rose M. Singer Center, almost all participants reported receiving breastfeeding education from family or community supports before incarceration, but reported only average ratings of breastfeeding knowledge, proficiency, and confidence. Most wanted to learn more about breastfeeding techniques, milk expression, and weaning, and many had misconceptions about how routine illnesses and substances, such as tobacco and medications, would affect their milk.28

Educational topics noted as priorities by pregnant incarcerated women as part of the development of a pilot support group included infant feeding and bonding with one's baby.19 Another quality improvement study to improve postpartum depression screening for incarcerated women in Milwaukee described participants' relief at being screened and their description of having “felt listened to” more than at any other time in a carceral setting. One unintended benefit of this empowering patient-centered screening was that it led to four of the mothers starting a milk expression program at the carceral facility.33 Unifying themes from these studies include a desire for comprehensive lactation education and support and the importance of lactation in postpartum bonding and well-being.

Key question 2: how do hospitals, clinical providers, prisons, and jails support, encourage, or enable “successful” lactation and use of human milk for incarcerated women?

Fifteen studies identified hospital and carceral facility support for lactation.12,14,17–22,24–26,29,31,33,34 The primary interventions described were lactation policies, health care and carceral linkages, jail- or prison-based programs to enable lactation, prison nursery programs, and educational programs. There was also a subset of interventions focused on pregnancies affected by opioid use disorder (OUD).12–14,32,34

Lactation policies

One study found that seven prisons and two jails had written lactation policies about breastfeeding or milk expression.25 Another noted that carceral officers typically follow policies set forth by their institutions. Health care providers can review relevant policies and procedures from the carceral settings and develop educational and support groups to address gaps, in some cases by directly educating carceral staff on the benefits of lactation and the needs of breastfeeding mothers.17,19

Interventions to improve and align policies across health care and carceral facilities used tools such as resource binders, daily clinical reporting between institutions,17 and care coordinators liaising between different units and communicating information about women's rights.29 One case study described carceral staff and the health care team using guidelines from the Office of Women's Health to develop a policy for safe expression, handling, and storage of human milk.18

Another case study described how a group of perinatal clinicians researched recommendations for optimal perinatal care and identified legislative policies to challenge the use of shackles during labor, implement immediate postpartum skin-to-skin, and offer extended lactation support.23 However, one ethnographic study noted that the robust human milk pumping protocol used in one women's jail might be perceived by incarcerated birthing people to promote a particular kind of idealized motherhood that may be unattainable within the carceral system and contradictory to incarceration's violation of reproductive autonomy.31

Health care and carceral linkages

While most women do not receive lactation support in carceral settings, where programs exist, they are often the result of linkages across health care and carceral workforces.17–20,22,29 A collaboration between health care providers and carceral center staff in Idaho led to cross-training between the two groups aligned with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and Association of Women's Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN) best practice guidelines. Mothers' support people were invited to participate in the birth, and nurses encouraged women to room-in with their newborns and actively participate in caretaking. If a woman wanted to breastfeed, she received help from a lactation consultant and was taught how to use a pump before discharge to establish and maintain a milk supply. Women were given access to unlimited infant visits at the carceral facility in a redesigned family-centric room, where women breastfeed or provide their expressed milk.17

Another study described an agreement between a carceral facility and health care providers that directed the acquisition of pumps, education for facility employees and inmates, and provision of lactation specialists for ongoing guidance and support. Of the 17 births since the program's inception, 6 women chose to participate, and 2 were released 6 weeks after childbirth and reported planning to continue breastfeeding. One participant was able to express milk and have it delivered to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit for the entire time her infant was hospitalized after birth.22

Another case study described a health care team, carceral guards, and an incarcerated woman's family working together to support the mother to express and store milk, noting that at 10 days of age, the infant was exclusively breast milk fed.20 A program developed by health care providers working in a Northeastern women's prison involved coordination with the prison warden to gain buy-in for aligning practices with evidence-based standards. As part of improvements made to prenatal care, a lactation consultant was available to meet with all women individually to discuss breastfeeding.18

Successful programs addressed multiple steps from the BFHI framework, including improved prenatal education, staff training, lactation support, and discharge planning and coordination to identify creative logistics to overcome separation and maintain lactation. Establishing formal linkages between health care providers caring for incarcerated women at birth and staff within the prison or jail, such as the nursing and medical staff, can improve continuity of care, interinstitutional commitment, and rapport between incarcerated women and the staff who are working to address their needs.18,19,29

Jail- or prison-based programs to enable lactation

Most incarcerated mothers are unable to reside with their infant after birth. Women in prison often serve longer sentences in locations far from their home communities, while women in jails and juvenile residential facilities typically have shorter stays in locations near their homes. While these differences create unique challenges for lactation, programs have been developed within both settings to support women to express milk and maintain their milk supply during separation from their infants so that they may breastfeed or continue to provide human milk for their infant after release.

Two studies surveyed the current landscape of programs to support onsite milk expression in carceral facilities.25,26 A survey of 22 state prison systems and 6 county jails across the United States found that 5 prisons and 2 jails allowed women to express milk, but the milk must be discarded. Over a 6-month period at sites that allowed lactation, there were 207 women who gave birth in the prisons and an average of 8 women per month who expressed milk.

At the jails, there were 67 women who gave birth and an average of 6 women per month who expressed milk. One prison supported daily visits with the infant in the first 6 weeks, but only allowed milk expression and not direct breastfeeding.25 A survey of juvenile residential systems in three states found that all three allowed breastfeeding during newborn visitations. In addition, two sites permitted mothers to express milk and have it delivered to their infant.26

Eight articles described jail- or prison-based interventions to support incarcerated mothers to express milk.12,17,18,20–22,29,33 In 2004, as part of efforts to increase breastfeeding rates in Alabama, the Alabama Breastfeeding Committee (ABC) formed, partnering with the Alabama Prison Project to provide pumps to incarcerated mothers and to facilitate the shipment of frozen milk to infant caregivers.21 In a Northeastern U.S. women's prison, a carceral nurse worked with the prison medical and custody staff to develop a procedure to simultaneously maintain security and safeguard women’ right to express milk.18