Abstract

Objective:

The nociceptive system has been implicated in acupuncture analgesia, although acupuncture's precise mechanism of action remains unknown. Electric pain-related evoked potentials (PREPs) have emerged as an effective and reliable electrophysiologic method for evaluation of the human nociceptive system by electric stimulation of nociceptive Aδ and C fibers. This pilot mechanistic study aims to assess the feasibility of using advanced PREP techniques together with electroacupuncture and to use PREPs to characterize acupuncture's effect on nociception.

Methods:

Seven healthy volunteers underwent a previously designed electroacupuncture protocol using acupoints in the legs bilaterally, which has been demonstrated to induce systemic analgesia. Advanced PREP techniques involving tripolar stimulating electrode, varying interstimulus interval, and incorporating a cognitive task during PREPs were used. PREPs were assessed before electroacupuncture, during electroacupuncture, and 30 min after electroacupuncture. Subjective pain perception in response to the PREP-related electric pain stimuli delivered to the nondominant hand was assessed on the visual analog scale (VAS) at baseline, during electroacupuncture, and 30 min postelectroacupuncture.

Results:

Reliable PREP N1, P1, and N2 waves were obtained from all subjects at the following average latencies: N1 = 131.5 msec, P1 = 189.4 msec, and N2 = 231.1 msec. Electroacupuncture caused a significant reduction in PREP N1P1 wave amplitudes from 25.6 to 15.4 μV (p = 0.006) and electric pain perception on the VAS—from 2.86 to 2.14 (p = 0.008), compared to baseline. These effects were sustained at 30 min postacupuncture with N1P1 wave amplitude 17.2 μV (p = 0.030) and VAS 2.28 (p = 0.030), compared to baseline.

Conclusions:

Electroacupuncture causes significant changes in objective nociception, measured by PREP N1P1 wave amplitudes, and in subjective nociception, measured by the VAS, and these effects are sustained for 30 min after electroacupuncture. Planned future studies will involve chronic pain populations and will aim to assess acupuncture's longer term analgesic effects.

Keywords: acupuncture, electroacupuncture, electric pain-related evoked potentials, nociception

Introduction

Multiple recent evidence-based reviews have demonstrated acupuncture's therapeutic benefits for chronic low back pain,1,2 migraine and tension headache3,4 and other pain conditions.5 Although the mechanisms underlying acupuncture analgesia are not fully understood, the nociceptive system appears to play a vital role in acupuncture's analgesic effects.6 Imaging studies such as functional magnetic resonance imaging7–10 and positron emission tomography11–13 have highlighted the role of the hypothalamus, limbic system, primary somatosensory cortex, and insula in acupuncture analgesia. There is also extensive evidence that acupuncture analgesia is mediated by various endogenous neurotransmitters involved in nociception.14

In animal models, acupuncture was shown to increase cerebrospinal fluid levels of endorphins, enkephalins, and adrenocorticotropic hormone,15 and its analgesic effect was reversed by naloxone.15,16 In our own research on healthy volunteers,17 we demonstrated that electroacupuncture has both local and systemic analgesic effects on self-reported nociception. Acupuncture caused significant increases in heat pain threshold, heat pain 5/10 perception, and cold detection threshold, measured by quantitative sensory testing (QST).

Electrophysiologic techniques offer a different perspective compared to imaging and animal studies, as they are noninvasive, are inexpensive, can be used repeatedly, and yield immediate results. One such technique is electric pain-related evoked potentials (PREPs), which have emerged as an effective and reliable electrophysiologic method for evaluation of the human nociceptive system by electric stimulation of nociceptive Aδ and C fibers.18–20

Recent advances in electric PREP techniques include the use of concentric tripolar electrodes, which can selectively target nociceptive fibers by focusing stimulation in the upper dermis layers; the use of varied interstimulus intervals to prevent habituation; and the use of a cognitive task to create uniform testing conditions across subjects.18–20 Performed under these conditions, PREPs have high test-retest reliability20,21 and negligible side-to-side differences, as demonstrated with consecutive bilateral stimulation of the hands.20 In healthy adults, PREP wave amplitudes have been shown to correlate significantly with self-reported pain scales.19,22 Furthermore, electric PREP wave amplitudes and latencies have been used as a reliable measure of the duration of analgesic effect of drugs such as fentanyl and buprenorphine at regular intervals after administration.23

The purpose of this pilot study was to assess the feasibility of using electric PREPs to capture acupuncture-induced systemic nociceptive changes. While older studies on acupuncture and PREP exist, to our knowledge, within the past 15 years, there are no studies that use advanced electric PREP techniques in conjunction with electroacupuncture. In addition to determining whether PREPs could be used as a measure of acupuncture analgesia, this pilot study aimed to establish their reproducibility by obtaining reliable waveforms before, during, and after acupuncture. To accomplish this, a standardized electroacupuncture protocol was applied using acupoints closely associated with the deep peroneal nerve bilaterally. These acupoints were shown to induce systemic analgesia in healthy volunteers in prior research.17 Acupuncture-induced systemic nociceptive changes were expected to cause reduced PREP wave amplitudes, which correlate with decreased pain perception.

Methods

This is a pilot nonrandomized study primarily intended to establish feasibility. Research volunteers were recruited from Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU)'s Study Participation Opportunities website. The study's recruitment advertisement, research protocol, consent form, and all other related materials were approved by OHSUs Institutional Review Board (IRB) and were carried out in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. Healthy male and female volunteers 18–45 years of age were screened through a telephone interview, using an IRB-approved telephone script.

The exclusion criteria aimed to exclude those unable to tolerate PREPs, those with contraindications to acupuncture, and those with chronic pain conditions (Table 1). Eligible volunteers were provided with additional information and scheduled for the study, which consisted of a single 3-h session. Upon arrival to the laboratory, the principal investigator answered all questions and obtained written informed consent. After enrollment, subjects underwent baseline PREP assessment as follows:

Table 1.

Study Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Male and female healthy volunteers, ages 18–45 years |

| Exclusion criteria | Pregnancy Coagulopathy/current anticoagulation treatment Implantable electronic device such as a cardiac pacemaker/AICD or vagus nerve stimulator Significant cognitive impairment such as ADHD, interfering with alertness, attention, and ability to participate in PREP recordings Hospitalization for anxiety or depression in the past 3 months Presence of a psychiatric diagnosis other than anxiety or depression Use of any investigational drug within the previous 6 months Presence of chronic pain condition such as neck and low-back pain. Presence of neuropathy or any other sensory impairment or other neurologic conditions Use of opioids, benzodiazepines, or other sedating medications, including sedating SSRIs Marijuana use in the past week Other illicit drug use in the past month Current EtOH abuse (>2 drinks/day) |

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; AICD, automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator; PREP, pain-related evoked potential; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Electric sensory detection threshold measurement

All electric stimuli and PREP recordings were conducted using the Cascade® Elite IONM System (Cadwell Industries, Inc., Kennewick, WA). A low-grade electric stimulus was delivered using Cascade Elite IONM system stimulator, beginning at 0.5 mA, using a 0.5 duration double pulse with an interwave interval of 5 msec. Stimulus intensity was increased and decreased by 0.5 mA in a series of three stimuli, until the subject reported stimulus detection.

Electric pain perception threshold measurement

Once the sensory detection threshold (SDT) was determined, stimulus intensity was increased, and then decreased by 0.5 mA in series of 3, using the same double-pulsed stimulus parameters as described under SDT measurement. Subjects were asked to report any pain, in addition to stinging, zappy, or tingly sensation associated with the electrical stimulus. Once pain was felt, subjects were asked to rate it on the visual analog scale (VAS 1–10). The pain perception threshold (PPT) was assessed in three separate trials and the highest PPT stimulation intensity was selected, to prevent sensitization. After the PPT was obtained, stimulus intensity was increased by 0.1 mA, until a subject reported pain intensity of 4/10 on the VAS. This was verified by going down by 0.1 mA and back up by 0.1 mA. All subsequent testing occurred at the stimulus intensity initially rated as 4/10, which was subject specific.

Electric PREP assessment

The scalp was prepped in a standard electroencephalography (EEG) manner and EEG leads were placed at Cz (recording), A1 (reference), and Fpz (ground), according to the international 10–20 system. A single tripolar concentric ring stimulating electrode24 was placed on the dorsal nondominant hand skin, over the distal second metacarpal, after the area was cleaned with alcohol. Subjects sat in a comfortable recliner chair for the duration of the experiment. Subjects wore earplugs to minimize anticipation through auditory cues and were instructed to close their eyes while relaxing their facial and body muscles.

Two or 3 blocks of 20 stimuli at the intensity previously rated 4/10 on the VAS were delivered with random interstimulus interval, ranging between 12 and 20 sec, and a fixed interblock interval of 5 min. As a way of sustaining focus, subjects were asked to count the number or stimuli delivered. At the end of each trial, they were asked to rate the last electric stimulus on the VAS. Each 20-stimuli block generated a single autoaveraged waveform trace and constituted a single trial. If the initial two trials were reliable and consistent, no third trial was conducted. If one of the initial two trials did not produce reliable waveforms, a third trial was conducted. Post-PREP VAS scores were averaged across trials per subject.

Signal processing

All PREP data were acquired using the Cascade Elite IONM System and its Cadwell Surgical Studio software (Cadwell Industries, Inc.). Data were analyzed offline using BrainVision Analyzer software (Version 2.2.0; Professional Edition), with a 70 Hz low pass filter, a 0.1 Hz high pass filter, and a 60 Hz notch filter. Cursoring and latency measurements were performed manually. The N1 wave was defined as the first negative (upward) wave with latency >100 msec, typically in the range of 120–140 msec.

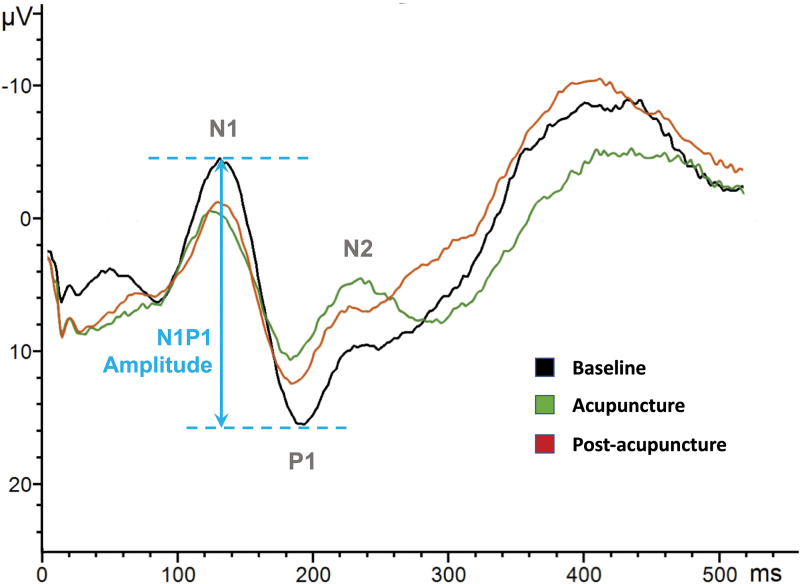

The P1 wave was assessed as the first positive (downward) wave after N1, typically in the range of 180–200 msec. N2 wave was assessed as the first negative wave after P1, typically in the range of 220–240 msec.18–20 N1P1 amplitude was measured as the vertical distance (in μV) between the peak of wave N1 and the trough of wave P1. After manual cursoring, the N1, P1, and N2 latency values and N1P1 amplitude were recorded for each trial and all available trial data (one to three trials) were averaged for each subject. In addition, all collected baseline PREP trials were averaged, generating a single averaged baseline trace for all seven trial participants.

Acupuncture intervention

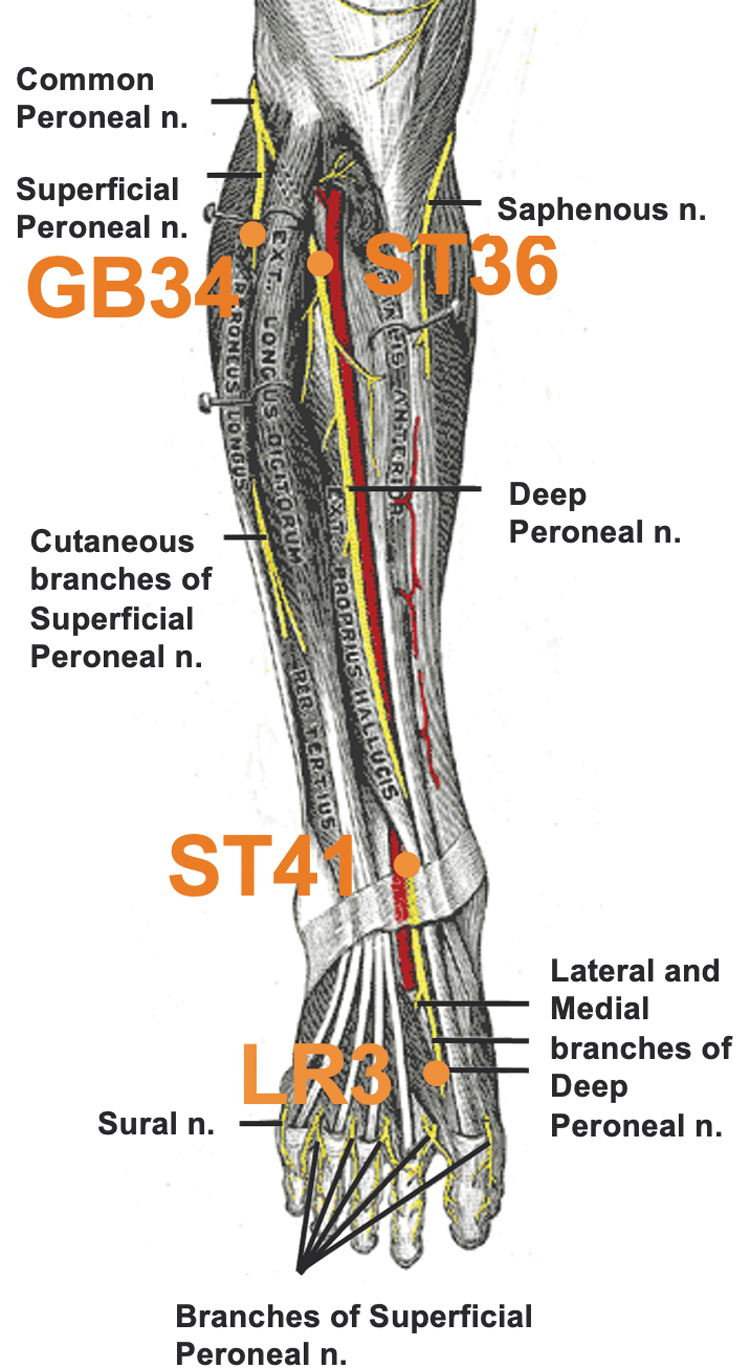

Following baseline PREPs, single-use Mac acupuncture needles (0.22 × 25 mm; Tianjin Empecs Medical Device Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) were placed in the following acupoints bilaterally: GB34, ST36, ST41, and LR3 (Fig. 1). Needling was performed by a medical acupuncturist, in accordance with standard clinical practice. Once the needles were placed, electroacupuncture was delivered to all acupoints at 100-Hz continuous stimulation using the Electrostimulator 6c.Pro (Pantheon Research, Venice, CA) for 20 min. The following acupoints were connected to the electroacupuncture device in pairs: GB34-ST36 and ST41-LR3, bilaterally. The stimulus intensity was titrated to a level the subject perceived as moderate stimulation and titrated every 5 min as needed to maintain a subject-rated level of moderate stimulation (typically in the range of 2–8 mA).

FIG. 1.

Acupoints used.

Acupuncture- and postacupuncture-PREP assessment

Acupuncture PREPs were obtained following 20 min of electroacupuncture, with the electroacupuncture still going, in the same manner as baseline PREPs. Once acupuncture-PREPs were obtained, electroacupuncture was discontinued, the needles were removed, and subjects were given a 30-min break, with PREP electrodes still affixed to their scalp and ears. Afterward, postacupuncture PREPs were obtained in a manner similar to baseline- and acupuncture-PREPs. All PREP signals were processed in the same manner as baseline PREPs.

Sample size estimation, statistical analysis plan

To our knowledge, the effect of electroacupuncture on advanced methodology PREPs has not been assessed before. There is a single somewhat similar study in the literature, in which 10 healthy volunteers underwent laser PREPs before and after abdominal and sham abdominal acupuncture.25 The authors were able to show differences between the verum and sham acupuncture. Our study has the advantage of using an acupuncture regimen, which has been shown to cause significant pain and cold analgesia measured by QST,17 whereas the authors of the study mentioned above did not test their acupuncture protocol in this way before PREPs.

Outcome variables included baseline, acupuncture and postacupuncture PREP wave N1, P1, and N2 latencies and N1P1 amplitudes and VAS scores. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 25 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY). Repeated-measures ANOVA using general linear model was calculated for each of the above PREP parameters. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed on statistically significant ANOVA values, using Fisher's least significant difference test.

Results

Seven healthy female (n = 6) and male (n = 1) volunteers 19–39 years of age (average 34.3) were tested. There was no study dropout, all seven subjects completed the single session successfully and were provided with contact information to report any potential side effect or concern, of which there was none reported.

For baseline PREPs, 13 averaged traces were obtained and analyzed. In one subject only a single 20-stimulus trial produced reliable waveforms. Seventeen acupuncture-PREPs were obtained and analyzed, which included three traces from three subjects, due to questions about waveform reproducibility and consistency. Fourteen traces of postacupuncture PREPs were obtained (two per subject). The mean baseline N1, P1, and N2 latencies were compared to the acupuncture and postacupuncture ones using repeated-measures ANOVA and were not statistically different. Acupuncture had a significant effect on N1P1 amplitude, F(2,12) = 5.91, p = 0.016.

On post hoc pair-wise means comparison, acupuncture caused significant reduction in N1P1 amplitude, from 25.6 μV at baseline down to 15.4 μV (p = 0.006). This effect persisted at 30 min postacupuncture, with N1P1 amplitude 17.2 μV and p = 0.030 compared to baseline (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference between the N1P1 amplitude during acupuncture and 30 min postacupuncture, p = 0.668. The composite average of all available PREP trials per condition is presented in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Pain-Related Evoked Potential Waveform and Visual Analog Scale Data

| PREP parameter | Baseline, mean ± SD | Acupuncture, mean ± SD | Postacupuncture, mean ± SD | ANOVA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 latency, msec | 131.5 ± 8.78 | 133.6 ± 7.56 | 133.3 ± 7.04 |

F = 0.68 p = 0.523 |

| P1 latency, msec | 189.4 ± 9.92 | 184.7 ± 9.11 | 184.4 ± 10.94 |

F = 2.04 p = 0.173 |

| N2 latency, msec | 231.1 ± 7.86 | 231.19 ± 9.11 | 231.39 ± 9.53 |

F = 0.004 p = 0.996 |

| N1P1 amplitude, μV | 25.6 ± 8.21 | 15.4 ± 8.94 | 17.2 ± 7.70 |

F = 5.91 p = 0.016 |

| N1P1 compared to baselinea | p = 0.006 | p = 0.030 | ||

| N1P1 compared to acupuncturea | p = 0.668 | |||

| VAS at PREP completion | 2.86 | 2.14 | 2.28 |

F = 9.0 p = 0.004 |

| VAS compared to baselinea | p = 0.008 | p = 0.030 | ||

| VAS compared to acupuncturea | p = 0.356 |

Values shown in bold are statistically significant.

Post hoc pairwise comparisons.

PREP, pain-related evoked potential; SD, standard deviation; VAS, visual analog scale.

FIG. 2.

Acupuncture-induced pain-related evoked potential changes.

Acupuncture caused significant reduction in VAS reporting of the experimental pain stimulus, F(2, 12) = 9.0, p = 0.004. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed. At baseline PREP completion, the mean VAS for the experimental pain dropped from 4.0 to 2.86. Acupuncture caused VAS at PREP completion to drop from 4.0 to 2.14, p = 0.008. VAS at PREP completion 30 min postacupuncture remained significantly reduced compared to baseline PREP completion VAS, with mean value of 2.28 (p = 0.030). There was no statistically significant difference between the PREP completion VAS scores during acupuncture and 30 min postacupuncture, p = 0.356 (Table 2).

Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was to establish feasibility for the use of advanced electric-PREP techniques together with electroacupuncture. The idea of using PREPs to assess acupuncture analgesia dates back to the 1970s. Saletu et al. published an early study,26 in which electric-PREPs were obtained using stimulation to the right median nerve, recorded from midline vertex and bilateral temporal lobes. Acupuncture was applied to two acupoints in the hand (LI4 and LU7). The authors used both manual and electroacupuncture at 130 Hz, for 20 min, and found that electroacupuncture, but not manual acupuncture, produced significantly lower subject pain ratings. Both manual and electroacupuncture had mixed effects on PREP wave latencies and amplitudes.

Studies from the early 1980s using dental pulp painful electric stimulation and recordings from Cz consistently demonstrated that acupuncture decreases the amplitude of late PREP components.27–29 In 1982, Chapman et al. used 30 healthy male volunteers, applied 2–3 Hz electroacupuncture to LI4 bilaterally for 20 min,27 and found that acupuncture caused significant reduction of P250 waveform amplitude and a nonsignificant reduction of N150 waveform amplitude. The same group found that 20 min of 2 Hz segmental acupuncture to two acupoints in the ipsilateral face caused significant reduction in P1N2, N2P2, and P2N3 amplitudes.28

Interestingly, when naloxone was administered and acupuncture continued, acupuncture's effect on waveform amplitudes was not reversed. In both studies, subjective pain ratings corresponded with waveform amplitude changes. Schimek et al.29 used the same dental pain PREP technique to show that only high-intensity electroacupuncture (perceived as high in intensity, but not painful) caused changes in PREP wave amplitudes, whereas lower electroacupuncture intensities had no effect on PREP waveform amplitudes.

In 2006, Zeng et al. recorded electric PREPs at the Cz electrode from the left median nerve at baseline, during electroacupuncture at acupoint LI4 in the left hand, and during electroacupuncture to a nonacupoint close to LI4.30 Continuous painful stimulation (2 Hz) for 20 min was applied at the median nerve using intradermal needle electrodes, also at LI4 and at the sham acupoint for comparison. Electroacupuncture to LI4 caused significant amplitude reduction at N80, P170, N280, N20-P40 N80-P170, and P170–N280.

The nonacupoint electric stimulation also produced reduced amplitudes in the above waveforms, but the amplitude reduction was significantly lower, compared to LI4. The observed amplitude changes corresponded to subjects' reported pain perception on the VAS 0–100. The authors did not assess postacupuncture PREPs, did not justify the use of continuous stimulation frequency, and did not address habituation or explain why acupuncture and “sham” acupuncture were applied in such proximity to the median nerve.

Over the past 15 years, advances in electric PREP methodology have produced reliable stimulation techniques, in which only the nociceptive Aδ and C fibers are stimulated using tripolar concentric ring electrodes, which allow for more precise targeting and stimulation in the upper layers of the dermis only.18–20 Strategies for reducing habituation such as using varied interstimulus intervals and greater temporal dispersion of stimuli have also been adopted. In our study, we used a tripolar concentric ring electrode24 for targeted nociceptive fiber stimulation, adopted a variable stimulation interval of 12–18 sec, and gave subjects a 5-min break between PREP assessments, to minimize habituation. We also implemented a counting task, asking the subjects to count the number of stimuli delivered, to create uniform mental testing conditions and minimize distraction. Distraction is known to affect pain perception and PREP wave amplitudes.31

To our knowledge, a single study exists, in which advanced PREP techniques, including varied interstimulus intervals and cognitive task (counting), were applied together with acupuncture. Pazzaglia et al. recruited 10 healthy male and female volunteers, obtained CO2 laser PREPs by stimulating the dorsum of both wrists and recording from Cz and contralateral temporal cortex T3/T4.25 The baseline PREPs were compared to acupuncture PREPs and to 15 min postacupuncture PREPs. The authors' findings were consistent with our own and showed significantly decreased N2P2 amplitudes with acupuncture, which persisted at 15 min postacupuncture, without significant acupuncture effect on PREP latencies. This is the only available PREP study that assessed nociception postacupuncture.

We were able to report similar persistence of acupuncture's nociceptive effect at 30 min postacupuncture. In addition, the authors also included nonpenetrative sham acupuncture to the same group of acupuncture-naive subjects in a blinded manner, which did not cause significant reduction in N2P2 amplitudes. Abdominal acupuncture caused decreased pain perception, which trended toward significance, p = 0.06. We observed a greater, statistically significant drop in self-reported pain perception on the VAS from baseline (p = 0.008), which can be attributed to the use of electroacupuncture. Electroacupuncture is hypothesized to have greater analgesic effects compared to manual acupuncture.32

There are various technical aspects of obtaining PREPs, which could make the presence of a continuous electric current such as 100 Hz used in high frequency electroacupuncture challenging. We encountered somewhat increased artifact in the traces obtained during electroacupuncture, compared to baseline and postacupuncture; however, artifact rejection and signal processing using both the Cascade Elite IONM System (Cadwell Industries, Inc.) and the BrainVision Analyzer software (Version 2.2.0; Professional Edition) essentially eliminated this issue. The choice of acupoints distal to the knee helped minimize electric artifact from electroacupuncture.

Our secondary purpose was to assess whether electric-PREPs could be used to capture reliably and reproducibly electroacupuncture's nociceptive effect. Even with the significant acupuncture-induced changes in PREP amplitudes, we observed nearly identical average latencies of N1, P1, and N2 and there was little intrasubject variability in latencies across conditions. Furthermore, we were able to obtain waves N1, P1, and N2 from all seven subjects, across all testing conditions.

Study limitations and future directions

Our study was limited in that we only tested healthy volunteers. Future studies should include chronic pain patients and compare their findings to those of healthy controls. Psychological aspects of chronic pain, such as pain catastrophizing, are associated with reduced pain habitation,33 increased pain sensitization,34 and increased perceived pain bothersomeness.33–35 In line with these findings, chronic pain patients have been shown to have increased NP amplitudes on PREP recordings compared to healthy controls,36–38 which correspond to higher levels of perceived nociception. The nociceptive effects of acupuncture, measured by PREPs, have not been studied in chronic pain populations. We expect to find a greater effect on PREP waveform amplitudes in future studies on chronic pain patients.

Another limitation is the nonblinded nature of this trial. It is possible that some of the nociceptive effects captured on the VAS during and postacupuncture could be attributed to the placebo effect, in addition to acupuncture. Future studies should include a sham-acupuncture condition in a blinded manner, with test of blinding and assessment of pretesting bias such as attitudes toward acupuncture. Applying sham acupuncture to the same acupoints as a control condition will help study the extent of nociceptive effects due to placebo and compare them to those caused by acupuncture. Finally, since our recording of PREPs was limited to Cz, additional localization of acupuncture's nociceptive effects was beyond the scope of this project.

Conclusion

We recorded electric PREPs using tripolar concentric ring electrodes, under standardized conditions, which minimized distraction and habituation and were able to capture acupuncture's nociceptive effects, which were expressed as significant drop of N1P1 amplitudes in seven healthy volunteers. These changes persisted at 30 min postacupuncture. Our PREP measurements correlated with significant reduction in subject-reported pain perception at the VAS during acupuncture and at 30 min postacupuncture.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Walt Besio, PhD, at CREMedical for developing and providing tripolar concentric ring electrodes used for electric stimulation in this project.

This work was presented as an abstract at the Society for Acupuncture Research conference in June 2021 and the abstract was published in the conference proceedings. JICM 2021;27(11);A1–A30. http://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2021.29097.abstracts.

Authors' Contributions

A.D. lead the development of the study, supervised all aspects of the study, and drafted the article. A.H. and J.S. provided expertise on all stages of the study and assisted with recruitment, experimental procedures, data collection, and article revisions. T.M. assisted with signal analysis, provided programming and Brain Vision expertise, and assisted with article revisions. B.O. provided expertise with evoked potentials, signal processing, and was involved in all stages of the study.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This study was funded by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health grant NIH K23 AT008405.

References

- 1. Manheimer E, White A, Berman B, et al. Meta-analysis: Acupuncture for low back pain. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:651–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Furlan AD, van Tulder M, Cherkin D, et al. Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain: An updated systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane collaboration. Spine 2005;30:944–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B, et al. Acupuncture for the prevention of episodic migraine. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;2016:CD001218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B, et al. Acupuncture for the prevention of tension-type headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;4:CD007587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: Individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1444–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhao ZQ. Neural mechanism underlying acupuncture analgesia. Prog Neurobiol 2008;85:355–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hui KK, Liu J, Makris N, et al. Acupuncture modulates the limbic system and subcortical gray structures of the human brain: Evidence from fMRI studies in normal subjects. Hum Brain Mapp 2000;9:13–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hui KK, Liu J, Marina O, et al. The integrated response of the human cerebro-cerebellar and limbic systems to acupuncture stimulation at ST 36 as evidenced by fMRI. Neuroimage 2005;27:479–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang WT, Jin Z, Cui GH, et al. Relations between brain network activation and analgesic effect induced by low vs. high frequency electrical acupoint stimulation in different subjects: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Brain Res 2003;982:168–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang WT, Jin Z, Huang J, et al. Modulation of cold pain in human brain by electric acupoint stimulation: Evidence from fMRI. Neuroreport 2003;14:1591–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Biella G, Sotgiu ML, Pellegata G, et al. Acupuncture produces central activations in pain regions. Neuroimage 2001;14:60–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hsieh JC, Tu CH, Chen FP, et al. Activation of the hypothalamus characterizes the acupuncture stimulation at the analgesic point in human: A positron emission tomography study. Neurosci Lett 2001;307:105–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pariente J, White P, Frackowiak RS, et al. Expectancy and belief modulate the neuronal substrates of pain treated by acupuncture. Neuroimage 2005;25:1161–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cheng RS, Pomeranz B. Electroacupuncture analgesia could be mediated by at least two pain-relieving mechanisms; endorphin and non-endorphin systems. Life Sci 1979;25:1957–1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pomeranz B, Cheng R. Suppression of noxious responses in single neurons of cat spinal cord by electroacupuncture and its reversal by the opiate antagonist naloxone. Exp Neurol 1979;64:327–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pomeranz B, Chiu D. Naloxone blockade of acupuncture analgesia: Endorphin implicated. Life Sci 1976;19:1757–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dimitrova A, Colgan DD, Oken B. Local and systemic analgesic effects of nerve-specific acupuncture in healthy adults, measured by quantitative sensory testing. Pain Med 2020;21:e232–e242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Katsarava Z, Ayzenberg I, Sack F, et al. A novel method of eliciting pain-related potentials by transcutaneous electrical stimulation. Headache 2006;46:1511–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oh KJ, Kim SH, Lee YH, et al. Pain-related evoked potential in healthy adults. Ann Rehabil Med 2015;39:108–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ozgul OS, Maier C, Enax-Krumova EK, et al. High test-retest-reliability of pain-related evoked potentials (PREP) in healthy subjects. Neurosci Lett 2017;647:110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kramer JL, Taylor P, Haefeli J, et al. Test-retest reliability of contact heat-evoked potentials from cervical dermatomes. J Clin Neurophysiol 2012;29:70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kakigi R, Watanabe S. Pain relief by various kinds of interference stimulation applied to the peripheral skin in humans: Pain-related brain potentials following CO2 laser stimulation. J Peripher Nerv Syst 1996;1:189–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gram M, Graversen C, Nielsen AK, et al. A novel approach to pharmaco-EEG for investigating analgesics: Assessment of spectral indices in single-sweep evoked brain potentials. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2013;76:951–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Makeyev O, Ding Q, Besio WG. Improving the accuracy of Laplacian estimation with novel multipolar concentric ring electrodes. Measurement (Lond) 2016;80:44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pazzaglia C, Liguori S, Minciotti I, et al. Abdominal acupuncture reduces laser-evoked potentials in healthy subjects. Clin Neurophysiol 2015;126:1761–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saletu B, Saletu M, Brown M, et al. Hypno-analgesia and acupuncture analgesia: A neurophysiological reality? Neuropsychobiology 1975;1:218–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chapman RC, Colpitts YM, Benedetti C, et al. Event-related potential correlates of analgesia; comparison of fentanyl, acupuncture, and nitrous oxide. Pain 1982;14:327–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chapman RC, Colpitts YM, Benedetti C, et al. Evoked potential assessment of acupunctural analgesia: Attempted reversal with naloxone. Pain 1980;9:183–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schimek F, Chapman CR, Gerlach R, et al. Varying electrical acupuncture stimulation intensity: Effects on dental pain-evoked potentials. Anesth Analg 1982;61:499–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zeng Y, Liang XC, Dai JP, et al. Electroacupuncture modulates cortical activities evoked by noxious somatosensory stimulations in human. Brain Res 2006;1097:90–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yamasaki H, Kakigi R, Watanabe S, et al. Effects of distraction on pain perception: Magneto- and electro-encephalographic studies. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 1999;8:73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang R, Lao L, Ren K, et al. Mechanisms of acupuncture-electroacupuncture on persistent pain. Anesthesiology 2014;120:482–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meints SM, Mawla I, Napadow V, et al. The relationship between catastrophizing and altered pain sensitivity in patients with chronic low-back pain. Pain 2019;160:833–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Roussel NA, Nijs J, Meeus M, et al. Central sensitization and altered central pain processing in chronic low back pain: Fact or myth? Clin J Pain 2013;29:625–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bar-Shalita T, Granovsky Y, Parush S, et al. Sensory modulation disorder (SMD) and pain: A new perspective. Front Integr Neurosci 2019;13:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Obermann M, Yoon MS, Ese D, et al. Impaired trigeminal nociceptive processing in patients with trigeminal neuralgia. Neurology 2007;69:835–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kumru H, Soler D, Vidal J, et al. Evoked potentials and quantitative thermal testing in spinal cord injury patients with chronic neuropathic pain. Clin Neurophysiol 2012;123:598–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sohn JH, Kim CH, Choi HC. Differences in central facilitation between episodic and chronic migraineurs in nociceptive-specific trigeminal pathways. J Headache Pain 2016;17:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]