Abstract

Retrons are a class of retroelements that produce multicopy single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and participate in anti-phage defenses in bacteria. Retrons have been harnessed for the overproduction of ssDNA, genome engineering and directed evolution in bacteria, yeast and mammalian cells. Retron-mediated ssDNA production in plants could unlock their potential applications in plant biotechnology. For example, ssDNA can be used as a template for homology-directed repair (HDR) in several organisms. However, current gene editing technologies rely on the physical delivery of synthetic ssDNA, which limits their applications. Here, we demonstrated retron-mediated overproduction of ssDNA in Nicotiana benthamiana. Additionally, we tested different retron architectures for improved ssDNA production and identified a new retron architecture that resulted in greater ssDNA abundance. Furthermore, co-expression of the gene encoding the ssDNA-protecting protein VirE2 from Agrobacterium tumefaciens with the retron systems resulted in a 10.7-fold increase in ssDNA production in vivo. We also demonstrated clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats-retron-coupled ssDNA overproduction and targeted HDR in N. benthamiana. Overall, we present an efficient approach for in vivo ssDNA production in plants, which can be harnessed for biotechnological applications.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: retron, ssDNA, VirE2, HDR, CRISPR-Cas9

1. Introduction

Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) has been widely used for various bioengineering and synthetic biological studies. For instance, ssDNA is used in DNA nanotechnology, DNA repair, drug delivery, molecular diagnostics and DNA-based data storage (1). In genome engineering, ssDNA is used as a donor repair template (DRT) to introduce the desired mutations in the target DNA via homology-directed repair (HDR) (2, 3). In vitro-synthesized ssDNA is artificially delivered into cells through different physical approaches (4, 5). However, delivery of exogenous ssDNA in the target host remains challenging. Delivery strategies of exogenous ssDNA vary by host and are generally do not provide sufficient amounts of ssDNA for efficient HDR in vivo (4, 5). To accelerate the applications of ssDNA, a potential technology for the in vivo production of ssDNA is indispensable.

Retrons are a class of retroelements found in diverse prokaryotic cells (6, 7). In nature, retrons function as phage defense systems in bacteria (8). A wild-type (WT) retron usually comprises two components in a continuous polycistronic genomic cassette: a bacterial reverse transcriptase (RT) and retron non-coding RNA (ncRNA). The retron ncRNA generally includes the msr and msd. msr is the immediate precursor during multicopy single-stranded DNA (msDNA) production, while msd encodes the template sequence for reverse transcription. Upon transcription, the msr and msd RNAs form a unique secondary structure, which can be recognized by the bacterial retron RT, which initiates reverse transcription of the msd sequence using the conserved priming guanosine residue in the msr and produces msDNA molecules. The bacterial retron RT and the paired msr are crucial for the conversion of the msd template into msDNA. However, the internal msd sequence can be replaced with a DNA template containing any desired mutations (7).

Considering the potential of retrons as promising tools in molecular biology, two important improvements, enhancing ssDNA production by retrons and adapting retrons to work in more host organisms, are essential. Lopez et al. (9) demonstrated different strategies to improve ssDNA production in mammalian cells. Remarkably, the extension of the a1/a2 region of the retron ncRNA facilitated higher ssDNA production in mammalian cells (9). Viswanathan et al. (10) downregulated the expression of the endogenous exonuclease and showed efficient retron-mediated genome editing in Escherichia coli. Their study showed the importance of protecting in vivo ssDNA from the cellular exonuclease. We hypothesized that the ssDNA could be protected by natural ssDNA-protecting proteins, such as VirE2 from Agrobacterium tumefaciens, which is involved in the protection of larger T-DNA molecules during Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. VirE2 can bind the T-strand cooperatively, protecting it from degradation in plant cells (11, 12). Therefore, we hypothesized that VirE2 could aid retron-generated ssDNA protection and accumulation in the plant cells.

The development of efficient genome engineering tools has transformed the biotechnology field (13–17). Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein (Cas) genome editing systems have revolutionized plant biotechnology by allowing for precise genome modifications (14, 18–20), but targeted editing via HDR remains challenging, especially in multicellular eukaryotes, including plants (2). HDR requires a repair template at the break site to edit the DNA sequence (21). Multiple approaches have been used to augment HDR efficiency. For example, DNA damage response factors, such as RAD18, stimulate HDR in mammalian cells (21). Prime editing uses a chimeric fusion protein of an RNA-guided DNA nickase and reverse transcriptase (M-MLV RT) to extend the genetic information engineered in an RNA template into the target sequence (22). Researchers have repurposed retrons as powerful tools for genome engineering in several organisms (6, 7, 23). For example, retrons have been coupled with CRISPR-Cas9 tools to enrich ssDNA templates at the targeted editing site for HDR in the yeast, bacteria, mammalian cells and plants (9, 24–26).

Here, we set out to build, test and establish an efficient retron system to enable enhanced ssDNA production in Nicotiana benthamiana. We harnessed the Ec86 retron system for ssDNA production. We employed Tobacco rattle virus (TRV)-RNA2 vectors for the expression of Ec86 ncRNA and pK2GW7 vector for Ec86 retron reverse transcriptase (Ec86 RT). We also tested various retron ncRNA architectures and found that Ec86 ncRNA containing an extension of the a1/a2 region up to 27 bp and a 6-bp msd stem length improved ssDNA production in N. benthamiana. For in vivo ssDNA protection, we co-expressed VirE2, encoding an ssDNA binding protein from Agrobacterium, together with the retron reagents in N. benthamiana. Additionally, we achieved precise genome editing using the CRISPR-Cas9-coupled retron systems and showed the potential applications of retron-mediated ssDNA production in plants.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plasmid design and construction

For ssDNA production, we cloned the Ec86 RT driven by the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S (CaMV35S) promoter into the pK2GW7 vector. To test the genome engineering possibilities, we cloned the Cas9-fused Ec86 RT under the CaMV35S promoter into the pK2GW7 vector. We built different Cas9 and Ec86 RT fusions (Retron-Editors) using a short flexible linker (XTEN) and a self-cleaving linker (T2A). To measure protein expression, we customized the Retron-Editors expression sequence downstream of the 3xFLAG sequence. All the above vectors were custom synthesized by GenScript Biotech.

For both the ssDNA production and Retron-Editors-mediated HDR studies, we placed the DRT within the msd loop of the retron and the Cas9 sgRNA at the 3′ end of both Ec86 ncRNA and modified Ec86 ncRNA designs termed Retro-sgRNA and mRetro-sgRNA, respectively. We selected two regions inside the NbPDS (phytoene desaturase) gene (PDS-1 and PDS-4) for targeted repair and designed the corresponding Retro-sgRNA and mRetro-sgRNA substrates. The complete Retro-sgRNA and mRetro-sgRNA sequences were ordered as gBlocks from Integrated DNA Technologies. Further, we digested the gBlocks with restriction enzymes (PDS-1 with XbaI and SacI, and PDS-4 with XbaI and XhoI) and cloned them under the Pea early browning virus (PEBV) promoter at corresponding restriction sites in the TRV-RNA2 vector (27).

For VirE2 expression, we isolated A. tumefaciens (strain GV3101) total genome and amplified the VirE2 gene sequence using full-length gene-specific primers (VirE2 KpnI forward—5′-AAGGTACCATGGATCCGAAGGCCGAAGGC-3′ and VirE2 SpeI reverse—5′-TTACTAGTCTACAGACTGTTTACGGTTGGGCCGCG-3′), appending the KpnI and SpeI restriction sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends. The VirE2 amplicons were then cloned under the CaMV35S promoter at KpnI and SpeI sites in the pMDC43 vector.

2.2. Plant material and Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation

Two- to three-week-old WT N. benthamiana plants grown under long-day conditions (16 h light/8 h dark at 25°C) were used for all leaf infiltration experiments. We transfected the pK2GW7 vectors containing Cas9-RT protein effectors and the TRV-RNA2 vectors containing the retron-sgRNA substrates into Agrobacterium GV3101 cells, independently. Agrobacterium cells harboring Cas9-RT protein effectors and retron-sgRNA substrates were co-infiltrated into N. benthamiana. For the ssDNA protection experiments, the Agrobacterium cells harboring the pMDC43 vector carrying a VirE2 gene expression unit were co-infiltrated together with the pK2GW7 and TRV-RNA2 vectors (27).

2.3. Western blot analysis

To check the Cas9-RT fusion protein accumulation, we conducted Western blot analyses. The infiltrated leaves were frozen and ground thoroughly in liquid nitrogen, and whole protein was extracted following a previously described method (28). Then, 30 μl of the protein was separated by an 8% polyacrylamide gel. The protein was transferred from the gel onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane as described by Mahas et al. (29). The membranes were incubated with primary antibody against α-FLAG antibody (1:2000, Invitrogen) and then anti-mouse antibody (1:1000, Invitrogen) to detect FLAG fusion proteins. Finally, the membrane was treated with an ECL detection reagent (Thermo Scientific) and observed under a chemiluminescent scanner.

2.4. Southern blot analysis

In vivo ssDNA production was detected by Southern blot analysis. ssDNA can be extracted together with the total RNA (30). Therefore, we isolated total RNA from all the infiltrated leaves using Invitrogen™ TRIzol™ reagent as described in the manufacturer’s protocol. Total extracted RNA (20 μg) from each target was used for the Southern blot experiment. We conducted independent Southern blot experiments for each target using 60 pg of the 140-bp amplified msd-DRT-msd fragment as a size range positive control. We used total RNA isolated from plants lacking the Ec86 RT (only transfected with RNA2-Retro-sgRNA or pK2-Cas9/RNA2-Retro-sgRNA and the WT) as negative controls. To distinguish the ssDNA from the total RNA, the same RNA samples without any nuclease treatment, with RNase treatment and with DNase treatment were run side by side in the same agarose gel for each target. In the case of plants containing modified retron architectures, such as RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-1, RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-2 and RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-3, we treated all the samples with RNase and ran them on an agarose gel. We then conducted the Southern blot experiment as described by Ali et al. (30).

For the corresponding PDS-1 and PDS-4 targets, we used 100-bp (only the DRT) DIG-labeled denatured DNA sequences as probes for the RNA2-Retro-sgRNA and RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA combinations in Southern blotting experiments. After the DIG-probe hybridization, the membrane was washed and treated with anti-digoxigenin-AP Fab fragments (Roche). The anti-digoxigenin-AP Fab fragments were then washed out, and the membrane was treated with CDP-star chemiluminescent substrate (Sigma life sciences). Finally, the membrane was imaged under the ChemiDoc imaging system (Bio-Rad) and evaluated by Image J software.

2.5. Amplicon deep sequencing

Amplicon deep sequencing was used to test the Retron-Editors-mediated precise genome engineering in N. benthamiana. We isolated the total genomic DNA from three independent infiltration experiments for each target (three different biological replicates) and performed deep amplicon sequencing. Subsequently, the ∼300-bp Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) fragment was amplified using high-fidelity Phusion polymerase with gene-specific primers mentioned in Primers_GeneFrags.fa file. The PCR amplicons were further purified and used for MiSeq library preparation. The library was prepared using TruSeq Nano DNA Library Prep kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. The libraries were run on the MiSeq platform, and the data were analyzed using online Cas-analyzer software (31). The HDR frequencies were determined as the ratio of HDR reads among the total reads with both indicators.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The raw data were analyzed and visualized by GraphPad Prism 9. All numerical data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. We included three independent biological replicates in amplicon deep sequencing experiments. For each replicate, both HDR and indel frequencies of the WT group and six experimental groups were measured. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were selected for statistical analysis to measure the differences among the indicated groups.

3. Results

3.1. Design and construction of retron systems for in planta expression

To harness the retrons for ssDNA production in plants, we designed and cloned EC86-RT downstream of the CaMV35S promoter in the pK2GW7 vector to construct the pK2GW7-RT vector and tested it in transient expression assays (Figure 1a). We adopted different strategies to exploit the retron functions for genome engineering applications (Figure 1b). We fused Cas9 and EC86-RT together using two different linkers, XTEN and T2A, to express the EC86-RT and Cas9 as a single or separate protein, respectively. Cas9 was located at the N-terminus, while EC86-RT was located on the C-terminus of the linkers. In another modality, we designed the EC86-RT on the N-terminus and Cas9 on the C-terminus using XTEN as the linker (Figure 1b). We cloned these cassettes under the control of the CaMV35S promoter on the pK2GW7 backbone. The pK2-RT and pK2-Cas9 constructs were used as controls for our experiments (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of retron-mediated production of exogenous ssDNA in vivo in N. benthamiana and design of vectors and donor templates for ssDNA production and genome engineering in N. benthamiana. (a) Retron Ec86-RT and Retron Ec86-ncRNA are expressed independently. Later, the Ec86 RT recognizes the hairpin structure in msr and initiate reverse transcription from the priming guanosine to synthesize msDNA. The mature msDNA, a DNA-RNA hybrid, consists of ssDNA and msr ncRNA. (b) Different vector backbones (pK2-Cas9-XTEN-RT, pK2-Cas9-T2A-RT, pK2-RT-XTEN-Cas9, pK2-RT and pK2-Cas9) used for the transient expression studies in N. benthamiana. (c) The N. benthamiana PDS gene sequence and the DRT sequences employed for repair by the Retron-Editor system.

We replaced the WT Ec86 ncRNA msd loop sequence with our 100-bp DRTs comprising the ∼47-bp homology arms and desired mutations for PDS-1 or PDS-4 targets (Figure 1b and c). The DRT sequences comprise different targeted mutations, including a 5-nt insertion (PDS-1) and a 6-nt deletion (PDS-4) (Figure 1c). To avoid re-targeting, we destroyed the protospacer adjacent motif sequences in the DRTs via a 1-nt substitution (Figure 1c). Employing the above-mentioned DRTs and sgRNA sequences of the PDS-1 and PDS-4 targets, we designed a basic Retro-sgRNA architecture that contained the 6-bp msd stem and a 12-bp a1/a2 arm (Figure 1b). We used the TRV-RNA2 vector system to express the Retro-sgRNAs under the PEBV promoter (Figure 1b). The annotated sequence plasmids are included in PlasmidSeqs.zip file.

3.2. Retron-mediated ssDNA production in N. benthamiana

To test whether retrons produce ssDNA in plants, we co-infiltrated the pK2-RT and RNA2-Retro vectors via Agrobacterium into young N. benthamiana leaves. We hypothesized that the RNA2-Retro vectors generate Retro-sgRNA transcripts in vivo, and then EC86-RT reverse transcribes the Retro-sgRNA transcripts to produce ssDNA in vivo. Leaves were sampled 3 days post-infiltration and used for molecular analysis.

We confirmed the protein expression from different Cas9-linker-Ec86 RT fusions in N. benthamiana. We observed a 200 kDa band corresponding to 3XFLAG-Cas9-XTEN-Ec86 RT and 3XFLAG-RT-XTEN-Cas9 from the pK2-Cas9-XTEN-RT and pK2-RT-XTEN-Cas9 constructs, respectively. We also observed an extra 170 kDa band corresponding to 3XFLAG-Cas9 in pK2-Cas9-XTEN-RT construct (Supplementary Figure S1). We assumed that the orientation of Cas9-XTEN-Ec86 RT fusion is unstable. The pK2-Cas9-T2A-RT construct produced a 170 kDa band corresponding to 3XFLAG-Cas9, indicating that the self-cleaving T2A linker was completely cleaved. Overall, our results confirmed that Cas9-linker-Ec86 RT was successfully expressed in N. benthamiana.

To detect and corroborate the production of ssDNA, we performed Southern blotting analysis and probed for the PDS-1 and PDS-4 targets. We extracted the total RNA and used it directly without any treatment. The same RNA was also treated with RNase to digest all the RNA and/or with DNase to digest all DNA. The RNA without treatment, RNase-treated and DNase-treated samples were run on the same blot to distinguish between RNA and DNA. The RNA without treatment showed strong signals, indicating the presence of various transcripts along with ssDNA (Figure 2). The DNase-treated samples also showed strong signals, representing the presence of retron transcripts (Figure 2). The RNase-treated samples showed a single band at 140 bp in all the targets with pK2-RT, pK2-Cas9-XTEN-RT, pK2-RT-XTEN-Cas9 and pK2-Cas9-T2A-RT backbones together with the corresponding RNA2-Retro-sgRNA construct, suggesting the production of ssDNA (Figure 2). However, the RNA2-Retro-sgRNA alone, RNA2-Retro-sgRNA with pK2-Cas9 and WT plants did not produce any ssDNA (Figure 2). The pK2-RT and pK2-Cas9-T2A-RT backbones showed much higher ssDNA production compared with the pK2-Cas9-XTEN-RT and pK2-RT-XTEN-Cas9 backbones (Figure 2). Overall, these results indicate that EC86-RT and Retro-sgRNA were expressed in the plant cells to produce ssDNA. However, pK2-Cas9-T2A-RT, where Cas9 and RT are produced as two separate proteins, showed higher ssDNA compared to the other designs.

Figure 2.

Southern blot analysis for the detection of ssDNA. Total RNA was isolated from N. benthamiana to detect PDS-1 and PDS-4 targets and run without any nuclease treatment, with RNase treatment, and with DNase treatment on an agarose gel side by side, together with the 140-bp amplified PDS-1 or PDS-4 msd-DRT-msd as a positive control. We used a 100-bp DIG-labeled DRT as a probe for the corresponding target. The membrane was imaged with the ChemiDoc imaging system (Bio-Rad).

3.3. Modifications in the retron architecture increased ssDNA production

To improve ssDNA production, we modified the retron architecture with different msd and a1/a2 arm lengths (Primers_GeneFrags.fa file). We designed mRetro-sgRNA-1 with a 6 bp msd stem and extended the a1/a2 arm up to 27 bp; in mRetro-sgRNA-2, we extended the length of the msd stem up to 18 bp and kept the a1/a2 arm length up to 12 bp. Similarly, in mRetro-sgRNA-3, the msd stem was extended up to 18 bp and the a1/a2 arm up to 27 bp (Figure 3a and Supplementary Figure S2a).

Figure 3.

Illustration of different retron structure modifications and Southern blot analysis for the detection of ssDNA in N. benthamiana containing different retron modifications. (a) Representation of the different retron structural modifications in msr and msd sequence lengths. (b)Total RNA was isolated from N. benthamiana to detect PDS-1 and PDS-4 targets and the RNase-treated samples were run on an agarose gel together with the 140-bp amplified PDS-1 or PDS-4 msd-DRT-msd as a positive control. We used a 100-bp DIG-labeled DRT as a probe for the corresponding target. The membrane was imaged with the ChemiDoc imaging system (Bio-Rad).

We tested the ssDNA production of the RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-1, RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-2 and RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-3 architectures together with the pK2-Cas9, pK2-RT and pK2-Cas9-T2A-RT backbones by Southern blot analysis. In order to compare the improvement of the modified retron designs, we also included the unmodified RNA2-Retro-sgRNA version together with the pK2-Cas9, pK2-RT and pK2-Cas9-T2A-RT backbones in the same Southern blotting experiment. Compared to the unmodified RNA2-Retro-sgRNA version, the new RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-1 version together with the pK2-RT and pK2-Cas9-T2A-RT backbones showed improved ssDNA production for both PDS-1 and PDS-4 targets (Figure 3b). However, the RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-2 and RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-3 architectures together with the pK2-RT and pK2-Cas9-T2A-RT backbones showed very little or no ssDNA production of the PDS-1 or PDS-4 targets (Figure 3b). As expected, all retron architectures with the pK2-Cas9 backbone did not show ssDNA production (Figure 3b). The extension of the a1/a2 region in the RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-1 version significantly improved ssDNA production, while the msd stem extension in both RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-2 and RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-3 architectures did not aid ssDNA production. The RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-1 version with a 6 bp msd stem and a 27 bp a1/a2 arm showed higher ssDNA production compared to the other designs. This further showed that modifications in the retron architecture affect ssDNA production.

3.4. VirE2 facilitated successful ssDNA production

We reasoned that in addition to retron architecture, there must be other factors that impact ssDNA production. One of these factors is the stability of the ssDNA after synthesis via reverse transcription. VirE2 is involved in the protection of ssDNA during Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (11). Therefore, we cloned VirE2 gene from Agrobacterium under the CaMV35S promoter in the pMDC43 vector and built the pMDC43-VirE2 vector (Supplementary Figure S2b). We performed Southern blotting with the N. benthamiana leaves co-infiltrated with the pMDC43-VirE2 vector together with the Cas9-RT effectors (pK2-Cas9, pK2-RT and pK2-Cas9-T2A-RT) and the retron substrates (PDS-1: RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-1 and PDS-4: RNA2-Retro-sgRNA, RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-1 and RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-3). We included RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-1 together with pK2-Cas9 and pK2-Cas9-T2A-RT without pMDC43-VirE2 as the experimental controls. Total RNA, including ssDNA from all the samples, was RNase-treated, and then Southern blotting was performed. As previously observed, RNA2-Retro-sgRNA and all the RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA sequences with the pK2-Cas9 backbone did not produce ssDNA. Interestingly, the co-expression of pMDC43-VirE2 with retron substrates (PDS-1: RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-1 and PDS-4: RNA2-Retro-sgRNA, RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-1 and RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-3) and pK2-RT and pK2-Cas9-T2A-RT showed a significant amount of ssDNA production compared to the samples without pMDC43-VirE2 (Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure S3). We analyzed the difference in ssDNA production between RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-1 co-expressed with VirE2 and without VirE2 by ImageJ software and found a 10.7-fold and 9-fold enhancement of ssDNA for PDS-1 and PDS-4 with VirE2 co-expression (Supplementary Figure S4a and b). These results demonstrated that VirE2 protected the ssDNA from degradation and therefore significantly enhanced the amount of ssDNA.

Figure 4.

Southern blot analysis for the detection of ssDNA in N. benthamiana co-expressing VirE2 and retron systems. Total RNA was isolated from N. benthamiana to detect the PDS-4 target, where RNase treated and the samples were run on an agarose gel together with the 140-bp amplified PDS-4 msd-DRT-msd as a positive control. We used a 100-bp DIG-labeled DRT as a probe. The membrane was imaged with the ChemiDoc imaging system (Bio-Rad).

3.5. Retron-Editors-mediated precise HDR in N. benthamiana

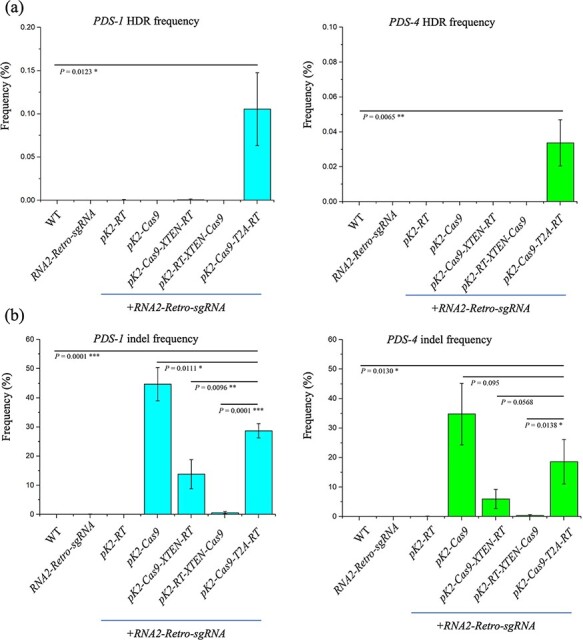

Because retron-mediated ssDNA has been used for HDR in the yeast and mammalian cells (9, 25), and because we successfully produced ssDNA with our retron designs, we hypothesized that retron-meditated ssDNA overproduction might facilitate HDR in N. benthamiana cells (Supplementary Figure S5). To test this, we extracted total genomic DNA from the infiltrated leaf samples (three independent biological replicates for each target), amplified the target DNA by PCR and used the PCR amplicons for deep sequencing. We initially tested the ability of all the Cas9-RT effectors, including pK2-Cas9, pK2-RT, pK2-Cas9-XTEN-RT, pK2-RT-XTEN-Cas9 and pK2-Cas9-T2A-RT, for HDR. The pK2-Cas9-T2A-RT construct with different RNA2-Retro-sgRNAs showed greater HDR frequencies: 0.1% ± 0.04% for PDS-1 and 0.03% ± 0.01% for PDS-4 targets (Figure 5a). However, the pK2-Cas9-XTEN-RT, pK2-RT-XTEN-Cas9 and pK2-RT constructs with different RNA2-Retro-sgRNAs did not show substantial HDR (Figure 5a). No HDR events were detected when only RNA2-Retro-sgRNA or RNA2-Retro-sgRNA was transfected with pK2-Cas9 (Figure 5a). The results showed that the Cas9-RT effectors mediated HDR editing in a RT and Cas9-dependent manner.

Figure 5.

Examination of Retron-Editor-mediated precision HDR and Cas9 indel frequencies in N. benthamiana. Deep amplicon sequencing of PDS-1 and PDS-4 targets with different Retron-Editors showed variable (a) HDR and (b) indel frequencies. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). P values were obtained using two-tailed Student’s t-tests in e and f. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Simultaneously, we examined double-strand break repair via non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), which produces insertions and deletions (indels). Among the three fusion backbones, we observed greater indel frequencies with pK2-Cas9-T2A-RT in all the targets, viz., 28.7% ± 2.4% (PDS-1) and 12.2–18.6% ± 7.5% (PDS-4) (Figure 5b). pK2-Cas9-XTEN-RT and pK2-RT-XTEN-Cas9 showed minimal indel frequencies (Figure 5b). As expected, pK2-Cas9 showed greater indel frequencies, whereas no indels were observed in only RNA2-Retro-sgRNA and pK2-RT with RNA2-Retro-sgRNA (Figure 5b).

To check whether higher ssDNA abundance can improve the HDR efficiency of Retron-Editors, we also conducted deep amplicon sequencing for the plants carrying the improved RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-1 architecture with pK2-Cas9-T2A-RT and with and without co-expression of the pMDC43-VirE2 vector. Unfortunately, we did not observe improvement in HDR efficiency with these modifications (Supplementary Table S1) and co-expression of the pMDC43-VirE2 vector (Supplementary Table S2). Overall, these results showed poor HDR frequencies in plant cells, and further modifications in the designs are needed to improve the repair efficiencies.

4. Discussion

In vivo ssDNA production would allow for expanded applications in various fields of study, including synthetic biology and nanotechnology, and for various bioengineering applications (1). Furthermore, the localized production of exogenous ssDNA to serve as a template for HDR is an important goal for genome editing studies. In genome engineering, the synthetic ssDNA is delivered into the targeted tissues by several physical methods (4, 5). Despite efforts, devising an efficient modality for in vivo ssDNA production remains a challenge. Retron systems produce ssDNA in vivo continuously in several organisms (7). Moreover, retrons enable ssDNA production in germline cells where the HDR machinery is predominant, leading to precise genome editing (25). Besides, the capability of retron-mediated ssDNA production has been further applied for continuous self-evolution (35), biological data storage (36, 37) and high-throughput functional variant screening (38). The exploration of retron functions in planta would adapt these retron toolkits for plant biological applications. Considering retron Ec86 system has been well studied for ssDNA production and HDR in bacteria, yeast and mammalian cells (9, 25), we selected the retron Ec86 system to produce ssDNA in N. benthamiana. ssDNA production is dependent on the retron ncRNA structure and the retron RT (9, 32). Instead of using WT Ec86 ncRNA, we replaced the WT msd template with our DRT sequences (100 bp) at the msd loop region as suggested by Sharon et al. (25). Our results showed successful ssDNA production in N. benthamiana. Moreover, the production of ssDNA was more efficient with the pK2-Cas9-T2A-RT and pK2-RT constructs, which contain free RT protein. Since the abundance of ssDNA is directly related to the availability of retron RT, we assumed that the greater production of ssDNA with pK2-Cas9-T2A-RT was due to the availability of the independent Ec86 RT protein. The lower abundance of ssDNA in the XTEN-fused Retron-Editors, which produce Cas9-XTEN-RT fusion proteins, may result from steric hindrances and the functional inhibition of the RT protein. Our results also confirmed that ssDNA production is retron RT dependent, since no ssDNA was detected when RNA2-Retro-sgRNA with pK2-Cas9 or only RNA2-Retro-sgRNA was transfected into N. benthamiana leaves.

Lopez et al. (9) showed that extension of the length of the a1/a2 arm could aid in ssDNA production in E. coli, yeast and mammalian cells. In line with this, our modified retron architectures, such as RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-1 harboring a 6-bp msd stem and an a1/a2 arm (msr) extension up to 27 bp, showed that the a1/a2 extension improved ssDNA production. Since the a1/a2 region acts as a primer for reverse transcription, a longer a1/a2 region may better facilitate reverse transcription to improve ssDNA production (9). However, our results showed that extension of the msd stem length in RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-2 and RNA2-mRetro-sgRNA-3 caused adverse effects on ssDNA production. One potential explanation is that the secondary structure of retron ncRNA (reverse transcription region) becomes more complicated with the extension of msd stem region which would affect the reverse transcription for retron ssDNA (Supplementary Figure S6). We also speculated that the in vivo-produced ssDNA would be severely degraded by cellular exonucleases in plant cells and that ssDNA protection from cellular exonucleases might increase the abundance of ssDNA in vivo. VirE2 functions in T-DNA protection during Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (11). Therefore, we co-expressed VirE2 with the retron systems and found a 10.7-fold improvement of ssDNA production. Overall, we established a high-efficiency ssDNA production method via co-expression of VirE2 with the retron systems in N. benthamiana.

Additionally, we tested retron-based genome editing platforms (Retron-Editors) in N. benthamiana. Deep amplicon sequencing showed successful HDR repair by Retron-Editors, indicating that ssDNA can be harnessed as the repair template for HDR in plants. This also demonstrated the accuracy of ssDNA produced in plants. For Retron-Editors, the fusion of Ec86 RT with Cas9 on either N-terminal or C-terminal might affect the Cas9 activity. Therefore, the self-cleavage linker (T2A linker) should be selected for the linker between Ec86 RT and Cas9 for higher genome editing efficiency. After confirming the positive effects of VirE2 and the extension of the a1/a2 region on ssDNA production, we also tested these designs for genome editing. However, the new designs did not improve the HDR frequency, indicating that the abundance of ssDNA is not the limiting factor. Conversely, Lopez et al. (9) obtained around 60% of HDR edit in yeast cells via Cas9/retron-mediated precise genome editing in 48 h. The differentiation in the abundance of retron-produced ssDNA in yeast cells and planta could cause the difference. Compared with two-nucleotide modification, five-nucleotide modifications in this study are more difficult which might also result in lower HDR frequencies. Further efforts are needed to improve the HDR editing efficiency of Retron-Editors in plants. For example, VirE2 binding proteins (VIP1 and VIP2) have been reported to target the T-strand to regions of chromatin, promoting integration. The co-expression of VIP proteins and VirE2 may improve the targeting of ssDNA to chromatin so as to improve HDR efficiency (33). Suppressing the NHEJ pathways has also been reported to stimulate HDR repair significantly. Qi et al. (34) achieved a 5-fold to 16-fold enhancement in HDR editing in a ku70-mutant Arabidopsis. In the future, the downregulation of NHEJ key factors would also be tested to improve Cas9/Retron system. Additionally, we tested two loci in the PDS gene which showed clear variations in genome editing efficiencies in this study. Therefore, higher HDR efficiencies might be achieved if other target genes were tested in the future. In summary, this study proposed a new strategy for in vivo ssDNA production in plants, which will have great potential for various biological applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank members of the genome engineering and synthetic biology laboratory at KAUST for their critical discussion and technical help in this work.

Contributor Information

Wenjun Jiang, Laboratory for Genome Engineering and Synthetic Biology, Division of Biological Sciences, 4700 King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), Thuwal 23955-6900, Saudi Arabia.

Gundra Sivakrishna Rao, Laboratory for Genome Engineering and Synthetic Biology, Division of Biological Sciences, 4700 King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), Thuwal 23955-6900, Saudi Arabia.

Rashid Aman, Laboratory for Genome Engineering and Synthetic Biology, Division of Biological Sciences, 4700 King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), Thuwal 23955-6900, Saudi Arabia.

Haroon Butt, Laboratory for Genome Engineering and Synthetic Biology, Division of Biological Sciences, 4700 King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), Thuwal 23955-6900, Saudi Arabia.

Radwa Kamel, Laboratory for Genome Engineering and Synthetic Biology, Division of Biological Sciences, 4700 King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), Thuwal 23955-6900, Saudi Arabia.

Khalid Sedeek, Laboratory for Genome Engineering and Synthetic Biology, Division of Biological Sciences, 4700 King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), Thuwal 23955-6900, Saudi Arabia.

Magdy M Mahfouz, Laboratory for Genome Engineering and Synthetic Biology, Division of Biological Sciences, 4700 King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), Thuwal 23955-6900, Saudi Arabia.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at SYNBIO online.

Data availability

The sequence reads for amplicon deep sequencing experiments are now available under the BioProject ID PRJNA889753 in the NCBI databases.

Material availability statement

Materials used in this study can be made available upon request.

Funding

This work is supported by KAUST baseline funding to M.M.

Author contributions

M.M. conceived the project; W.J., G.S.R., R.A., H.B., R.K., and K.S. conducted the experiments; W.J., G.S.R., and M.M. analyzed the data; and W.J., G.S.R., H.B., and M.M. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement:

None declared.

Abbreviations

msDNA: multicopy single-stranded DNA

ssDNA: single-stranded DNA

HDR: homology-directed repair

DRT: donor repair template

RT: reverse transcriptase

References

- 1. Hao M., Qiao J. and Qi H. (2020) Current and emerging methods for the synthesis of single-stranded DNA. Genes, 11, 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Butt H., Eid A., Ali Z., Atia M.A., Mokhtar M.M., Hassan N., Lee C.M., Bao G. and Mahfouz M.M. (2017) Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing using a chimeric single-guide RNA molecule. Front. Plant Sci., 8, 1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ali Z., Shami A., Sedeek K., Kamel R., Alhabsi A., Tehseen M., Hassan N., Butt H., Kababji A., Hamdan S.M.. et al. (2020) Fusion of the Cas9 endonuclease and the VirD2 relaxase facilitates homology-directed repair for precise genome engineering in rice. Commun. Biol., 3, 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gao C. and Nielsen K.K. (2013) Comparison between Agrobacterium-mediated and direct gene transfer using the gene gun. In: Biolistic DNA Delivery. Springer, pp. 3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vinoth S., Gurusaravanan P. and Jayabalan N. (2013) Optimization of factors influencing microinjection method for Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of tomato. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol., 169, 1173–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Inouye S. and Inouye M. (1993) The retron: a bacterial retroelement required for the synthesis of msDNA. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 3, 713–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Simon A.J., Ellington A.D. and Finkelstein I.J. (2019) Retrons and their applications in genome engineering. Nucleic Acids Res., 47, 11007–11019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Millman A., Bernheim A., Stokar-Avihail A., Fedorenko T., Voichek M., Leavitt A., Oppenheimer-Shaanan Y. and Sorek R. (2020) Bacterial retrons function in anti-phage defense. Cell, 183, 1551–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lopez S.C., Crawford K.D., Lear S.K., Bhattarai-Kline S. and Shipman S.L. (2021) Precise genome editing across kingdoms of life using retron-derived DNA. Nat. Chem. Biol. 18, 199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Viswanathan M. and Lovett S.T. (1999) Exonuclease X of Escherichia coli: A NOVEL 3′-5′ DNase and DnaQ superfamily member involved in DNA repair. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 30094–30100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ward D.V. and Zambryski P.C. (2001) The six functions of Agrobacterium VirE2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 98, 385–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li X., Yang Q., Peng L., Tu H., Lee L.-Y., Gelvin S.B. and Pan S.Q. (2020) Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2 interacts with host nucleoporin CG1 to facilitate the nuclear import of VirE2-coated T complex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 117, 26389–26397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aouida M., Piatek M.J., Bangarusamy D.K. and Mahfouz M.M. (2014) Activities and specificities of homodimeric TALENs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet., 60, 61–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ali Z., Mahas A. and Mahfouz M. (2018) CRISPR/Cas13 as a tool for RNA interference. Trends Plant Sci., 23, 374–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aman R., Mahas A., Butt H., Ali Z., Aljedaani F. and Mahfouz M. (2018) Engineering RNA virus interference via the CRISPR/Cas13 machinery in Arabidopsis. Viruses, 10, 732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mahas A. and Mahfouz M. (2018) Engineering virus resistance via CRISPR–Cas systems. Curr. Opin. Virol., 32, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Knott G.J. and Doudna J.A. (2018) CRISPR-Cas guides the future of genetic engineering. Science, 361, 866–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Adli M. (2018) The CRISPR tool kit for genome editing and beyond. Nat. Commun., 9, 1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sedeek K.E., Mahas A. and Mahfouz M. (2019) Plant genome engineering for targeted improvement of crop traits. Front. Plant Sci., 10, 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zafar K., Sedeek K.E., Rao G.S., Khan M.Z., Amin I., Kamel R., Mukhtar Z., Zafar M., Mansoor S. and Mahfouz M.M. (2020) Genome editing technologies for rice improvement: progress, prospects, and safety concerns. Front. Genome Ed., 2, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nambiar T.S., Billon P., Diedenhofen G., Hayward S.B., Taglialatela A., Cai K., Huang J.W., Leuzzi G., Cuella-Martin R., Palacios A.. et al. (2019) Stimulation of CRISPR-mediated homology-directed repair by an engineered RAD18 variant. Nat. Commun., 10, 3395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Butt H., Rao G.S., Sedeek K., Aman R., Kamel R. and Mahfouz M. (2020) Engineering herbicide resistance via prime editing in rice. Plant Botechnol. J., 18, 2370–2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rao G.S., Jiang W. and Mahfouz M. (2021) Synthetic directed evolution in plants: unlocking trait engineering and improvement. Synth. Biol., 6, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Farzadfard F. and Lu T.K. (2014) Synthetic biology. Genomically encoded analog memory with precise in vivo DNA writing in living cell populations. Science, 346, 1256272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sharon E., Chen S.A., Khosla N.M., Smith J.D., Pritchard J.K. and Fraser H.B. (2018) Functional genetic variants revealed by massively parallel precise genome editing. Cell, 175, 544–557.e516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Molla K. A., Shih J., Wheatley M. S. and Yang Y. (2022) Predictable NHEJ insertion and assessment of HDR editing strategies in plants. Front. Genome Ed., 4, 825236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ali Z., Abul-Faraj A., Li L., Ghosh N., Piatek M., Mahjoub A., Aouida M., Piatek A., Baltes N.J. and Voytas D.F. (2015) Efficient virus-mediated genome editing in plants using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Mol. Plant, 8, 1288–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mishra M., Tiwari S. and Gomes A.V. (2017) Protein purification and analysis: next generation Western blotting techniques. Expert Rev. Proteom., 14, 1037–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mahas A., Aman R. and Mahfouz M. (2019) CRISPR-Cas13d mediates robust RNA virus interference in plants. Genome Biol., 20, 263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ali Z., Abulfaraj A., Idris A., Ali S., Tashkandi M. and Mahfouz M.M. (2015) CRISPR/Cas9-mediated viral interference in plants. Genome Biol., 16, 238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Park J., Lim K., Kim J.S. and Bae S. (2017) Cas-analyzer: an online tool for assessing genome editing results using NGS data. Bioinformatics, 33, 286–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kong X., Wang Z., Zhang R., Wang X., Zhou Y., Shi L. and Yang H. (2021) Precise genome editing without exogenous donor DNA via retron editing system in human cells. Protein Cell, 12, 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ward D.V., Zupan J.R. and Zambryski P.C. (2002) Agrobacterium VirE2 gets the VIP1 treatment in plant nuclear import. Trends Plant Sci., 7, 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Qi Y., Zhang Y., Zhang F., Baller J.A., Cleland S.C., Ryu Y., Starker C.G. and Voytas D.F. (2013) Increasing frequencies of site-specific mutagenesis and gene targeting in Arabidopsis by manipulating DNA repair pathways. Genome Res., 23, 547–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Simon A.J., Morrow B.R. and Ellington A.D. (2018) Retroelement-based genome editing and evolution. ACS Synth. Biol., 7, 2600–2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shipman S.L., Nivala J., Macklis J.D. and Church G.M. (2016) Molecular recordings by directed CRISPR spacer acquisition. Science, 353, aaf1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bhattarai-Kline S., Lear S.K., Fishman C.B., Lopez S.C., Lockshin E.R., Schubert M.G., Nivala J., Church G.M. and Shipman S.L. (2022) Recording gene expression order in DNA by CRISPR addition of retron barcodes. Nature, 608, 217–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schubert M.G., Goodman D.B., Wannier T.M., Kaur D., Farzadfard F., Lu T.K., Shipman S.L. and Church G.M. (2021) High-throughput functional variant screens via in vivo production of single-stranded DNA. PNAS, 118, e2018181118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The sequence reads for amplicon deep sequencing experiments are now available under the BioProject ID PRJNA889753 in the NCBI databases.