Abstract

Previous studies and ongoing research indicate the importance of an interaction between a putative receptor on dividing cells in hyperglycemia and the non-reducing end motifs of heparin stored in mast cell secretory granules and how this interaction prevents activation of hyaluronan synthesis in intracellular compartments and subsequent autophagy. This suggests a new role for endosomal heparanase in exposing this cryptic motif present in the initial large heparin chains on serglycin and in the highly sulfated (NS) domains of heparan sulfate.

Inactive hyaluronan synthases normally migrate to the plasma membrane where they are inserted and activated. Then they alternately add cytosolic substrates, UDP-glucuronate (UDP-GlcUA) and UDP-N-acetyl-d-glucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc), onto the reducing end of the elongating hyaluronan chain that is being extruded into the extracellular matrix [1,2]. Hyperglycemic mesangial cells stimulated to divide from G0/G1 to S phase activate hyaluronan synthases by a PKC pathway in intracellular membrane compartments – endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi and transport vesicles – in response to the elevated cytosolic UDP-substrate concentrations due to glucose stress. The abnormal deposition of the polyanionic hyaluronan macromolecules into the ER induces ER stress, autophagy and subsequent extrusion of an extracellular monocyte-adhesive hyaluronan matrix after completing cell division [1, 3, 4].

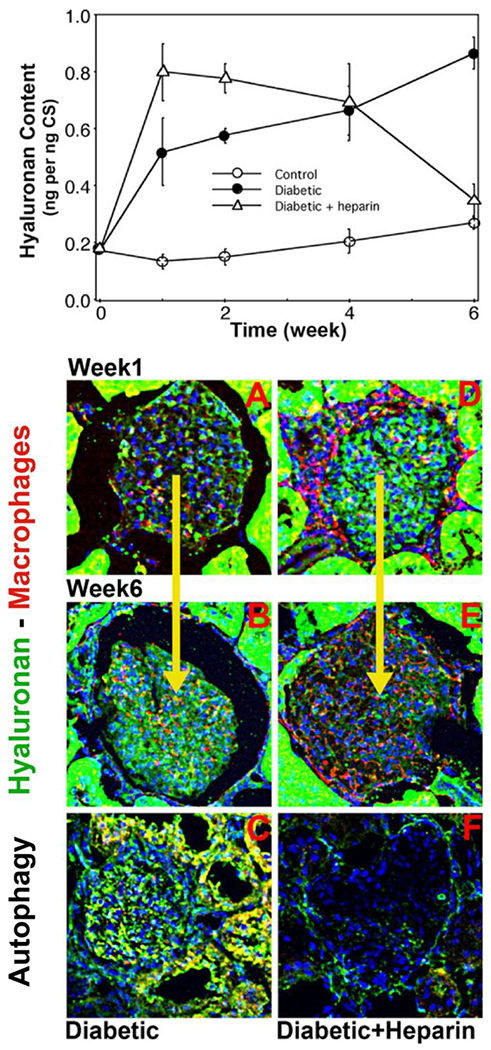

This mechanism occurs in kidneys of streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetic rats. Mesangial cells in the hyperglycemic kidney glomeruli initiate cell division within the first week with subsequent autophagy and continuous accumulation of an extracellular hyaluronan matrix, Fig. 1. This is accompanied by an influx of monocytes/macrophages that initiate pro-inflammatory and fibrotic responses that lead to nephropathy, proteinurea, weight loss and kidney failure by 6 weeks [4, 5].

Figure 1 –

HA concentrations in glomeruli isolated from kidneys 1-6 weeks after initiating diabetes in rats treated without or with heparin (IP) are shown in the upper panel. Sections of glomeruli from 1 and 6 week kidneys of diabetic rats (A-C) and diabetic rats treated with heparin (D-F) were stained for hyaluronan (green) and macrophages (red) (A, B, D, E), and for markers of autophagy, LC3 (green) and cyclin D3 (red) (C, F). Modified from figures in reference [5].

Previous studies showed that daily IP injection of a small amount of heparin in this diabetic rat model prevented the pathological responses and sustained kidney function for at least 8 weeks [6, 7]. To address the mechanisms involved, hyperglycemic mesangial cells were treated with a low concentration (2 μg/ml) of heparin after initiating progression from G0/G1 to S phase of cell division [5]. This prevented the activation of the hyaluronan synthases in the intracellular membrane compartments and allowed the cells to complete cell division without the ER stress and autophagy responses. However, it also re-programmed the cells to address the high glucose stress after completing cell division by inducing a large hyaluronan synthesis response at the plasma membrane with subsequent extracellular extrusion of an extensive monocyte-adhesive hyaluronan matrix.

This mechanism appears central to the glomerular responses in kidneys in heparin-treated diabetic rats [5], Fig. 1. Mesangial cells in glomeruli showed no autophagy responses over the 6-week period studied. Within the first week, the glomeruli accumulated an extensive extracellular hyaluronan matrix around the mesangial cells at which time there were few macrophages present in the glomeruli. By 6 weeks there were extensive numbers of macrophages in the glomeruli, and the hyaluronan matrix was reduced to near control levels. This provides evidence that the mesangial cells in the heparin-treated diabetic rats initiate and sustain a large synthesis of extracellular hyaluronan matrix to address the glucose stress while maintaining kidney function, and that the recruited macrophages in the glomeruli effectively remove the hyaluronan matrix without inducing mesangial cell inflammatory and fibrotic responses.

Fluorotagged heparin was used to track the binding and subsequent entry of the heparin into the dividing hyperglycemic cells [5]. It bound onto the cell surface within 1 hour after initiating cell division, was intracellular by 2 hours, and localized in the ER, Golgi and nuclei by 4 hours. Exposure of the cells to heparin for only 4 hours was sufficient to prevent the intracellular hyaluronan and autophagy responses, and to reprogram the cells to synthesize the extracellular monocyte-adhesive hyaluronan matrix after completing division. These results provide strong evidence that a cell surface receptor is involved in order to bind, internalize and transport the large (~15 kDa), highly polyanionic heparin to these intracellular compartments. Further, heparin interaction with this receptor would initiate activation of the intracellular pathways that: 1) inhibit the PKC activation of the hyaluronan synthases in the intracellular compartment membranes, and 2) initiate the mechanism that induces the synthesis of the extensive extracellular hyaluronan matrix after completing cell division.

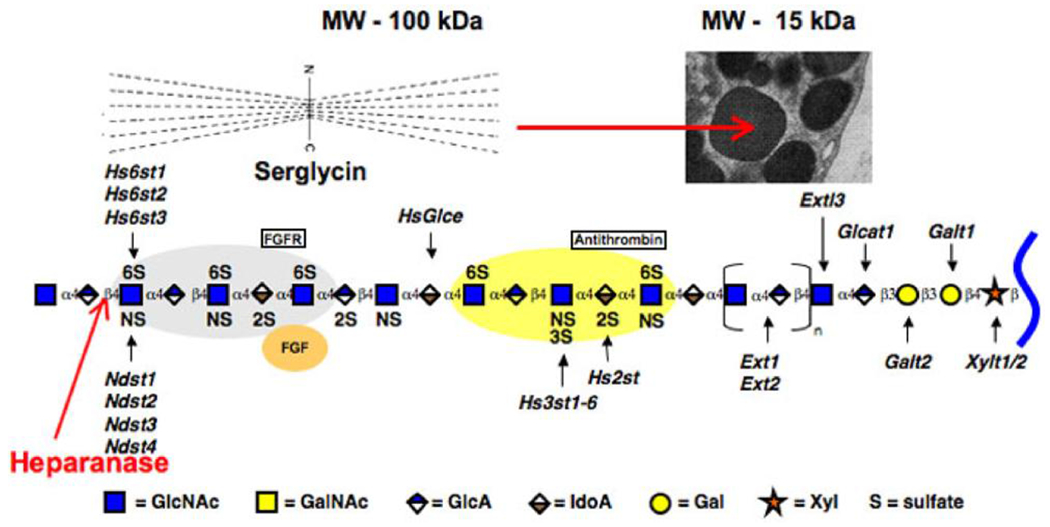

How does heparin do this? Heparin is synthesized by mast cells as the proteoglycan serglycin, which contains ~15 long heparin chains (~100 kDa) on a repetitive serine-glycine stretch in the core protein, Fig. 2 [8]. However, during or after its progression to the storage granules, the heparin chains are hydrolyzed into much smaller fragments (~15 kDa) by heparanase. This is the anti-coagulant form of heparin that is in extensive clinical use. There is only one heparanase in our genome, and it hydrolyzes the original intact heparin chain in regions that expose non-reducing terminal, GlcNS,-O-S residues on many of the fragments, Fig. 2, which is in good agreement with a previous report (see Table 1 in ref. [9]). These structural features of the cleavage sites of heparanase are based on in vitro recombinant heparanase digestion of defined heparin and heparan sulfate oligosaccharides followed by anion-exchange HPLC that indicated the predominance of the GlcNS,6-O-S residues and GlcNS,3-O-S residues at the non-reducing termini of the fragments. These non-reducing termini appear to be critical for the effect of heparin on hyperglycemic dividing cells as described below.

Figure 2 –

The model showing the FGF and antithrombin binding motifs of heparin/heparan sulfate and the enzymes that modify the backbone structure was provided by Jeff Esko. The site that heparanase could hydrolyze to expose a GlcN-S on the non-reducing end is indicated. The model for serglycin [8] is shown. The heparanase cleavage of the serglycin chains provides the heparin fragments that accumulate in the secretory granules of mast cells.

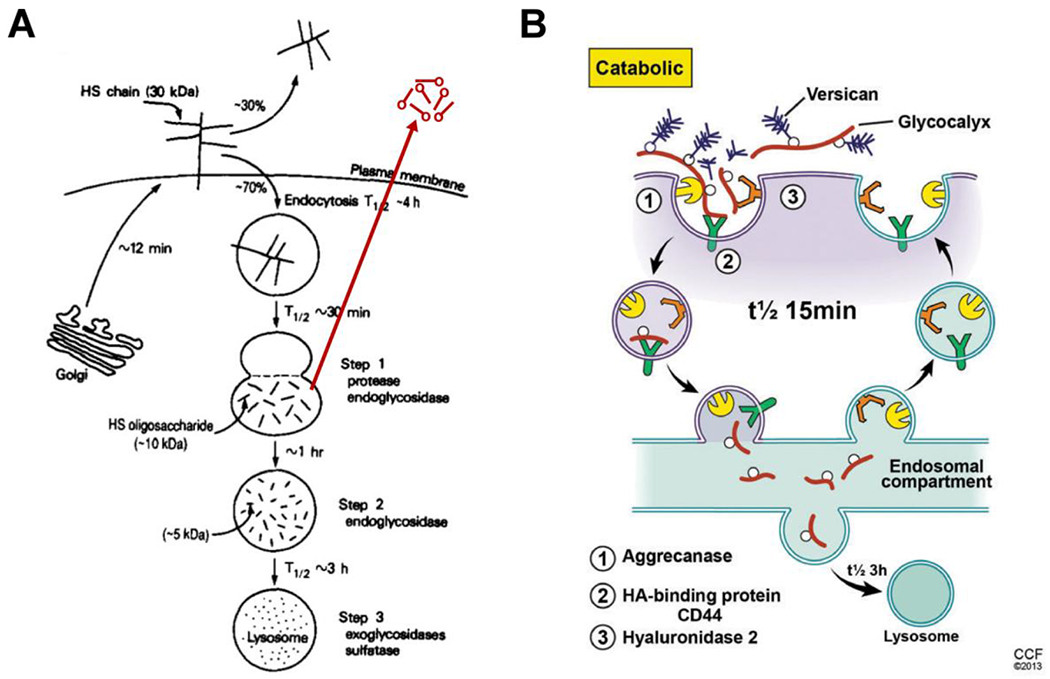

Heparanase is also directly involved in catabolism of heparan sulfate proteoglycans, Fig. 3A. Heparan sulfate chains are unique in that they have regions that are highly sulfated (NS domains) interspersed between unsulfated regions (NA domains). Although it has been generally assumed that the overall helical shape of HS remains the same for both domains, detailed modeling studies1 suggest that introduction of sulfate groups, as in NS domains, onto the unsulfated backbone, as in NA domains, introduces considerable changes in inter-glycosidic torsions (>20°) [10]. These changes appear to be directly related to the sulfation pattern, e.g., presence of GlcNS,6-O-S and/or GlcNS,3-O-S residues, and lead to formation of unique micro-domains at the NS/NA interface and within NS domains. It is well established that heparanase prefers sulfated regions, which suggests that the NS domains are in part designed to be effective substrates for the heparanase.

Figure 3 –

A. The model, reproduced from [13], shows how the cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan syndecan on ovarian granulosa cells is catabolized through an endosomal pathway. The modification (red) shows the ability of this pathway to recycle heparan sulfate fragments outside the cell as occurs in kidney mesangial cells [15, 16]. B. The model, reproduced from [1], shows how cell surface hyaluronan is catabolized on many cells.

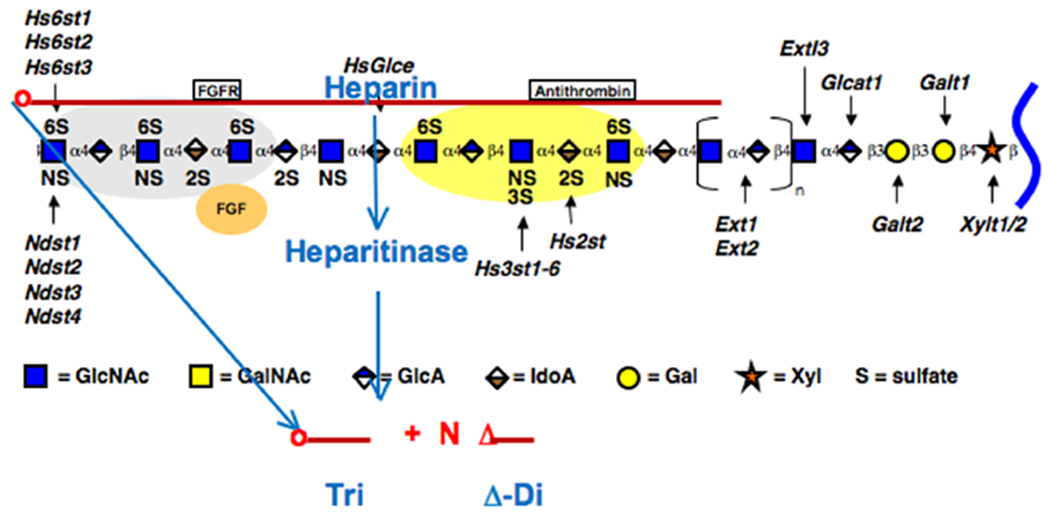

Previous studies [11] showed that ovarian granulosa cells catabolize the cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan syndecan by endocytosis into an endosomal compartment where the heparan sulfate chains are hydrolyzed to fragments of ~10,000 MW (t1/2 ~30 minutes). These fragments are then cleaved further and transported to lysosomes for complete degradation (t1/2 ~4 hours), Fig. 3A. Other studies [12–15] showed that cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans on confluent mesangial cells are catabolized by a similar mechanism with one exception. Endosomal fragmentation occurs within the first hour after internalization of syndecan with transport of some of the heparan sulfate fragments to lysosomes within 4 hours. However, a significant proportion of the heparan sulfate fragments are recycled into the medium with a t1/2 of <1 hour after entry into the cell, Fig. 3A. These fragments and the intact heparan sulfate chains isolated by proteolysis from the cell surface were tested for their ability to bind to growth arrested (G0/G1) rat mesangial cells (RMCs) in medium with a normal glucose concentration. The fragments have a significant antimitogenic effect while the intact chains are much less effective (~10 fold less than the fragments). Growth arrested RMCs possess a high-affinity, as yet unidentified receptor, that can bind and internalize heparin (~6.6 x 106 sites per cell with a Kd = 1.6 x 10−8 M) [15]. This study also showed that heparin bound to growth arrested smooth muscle A10 cells similarly and inhibited cell division. In contrast, confluent RMCs have fewer heparin-binding sites with 5-10 fold lower binding affinity, providing evidence that this putative receptor is primarily on G0/G1 cells. These results provide evidence that the exposure of the non-reducing terminal GlcNS,6-O-S or GlcNS,3-O-S by the heparanase is part of the ligand motif recognized by the receptor, Fig. 4.

Figure 4 –

The model shows how bacterial heparitinase eliminases can digest heparin fragments to release the non-reducing terminal trisaccharide.

Hyaluronan glycocalyces on keratinocytes, and likely on many cells, catabolize hyaluronan by a very similar mechanism – cell surface hyaluronidase 2 digests the hyaluronan into ~20,000 MW fragments that are transported to an endosome compartment (t1/2 ~15 minutes) followed by transport to lysosomes for complete degradation (t1/2 ~3 hours), Fig. 3B [1]. Cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans can also be internalized during this process. Therefore, heparanase is likely located in the same or a similar endosomal compartment that catabolizes hyaluronan.

Bacterial heparitinase eliminases digest heparin to mainly Δ-disaccharides and some resistant tri- and tetrasaccharides [16] while leaving the non-reducing terminal trisaccharide structure with GlcNS-O-S at the non-reducing end intact, Fig. 4. This trisaccharide retains the ability to prevent the intracellular hyaluronan synthesis and autophagy responses, and to induce the formation of the extensive monocyte-adhesive extracellular hyaluronan matrix after completing cell division (data not shown). This provides compelling evidence that the putative receptor recognizes a non-reducing terminal GlcNS-O-S trisaccharide motif on the heparin that was exposed by the heparanase.

Proposed Model – Heparanase exposes non-reducing terminal cryptic sites in heparin and heparan sulfate that are ligands for a specific receptor present on dividing cells. Heparin interaction with this receptor on hyperglycemic cells progressing from G0/G1 to S phase: 1) initiates intracellular responses that prevent activation of hyaluronan synthases in intracellular compartments by inhibiting the PKC pathway involved during cell division, and 2) re-programs the cell to increase synthesis of hyaluronan at the plasma membrane after completing cell division in order to prevent increases in cytosolic UDP-glucose and UDP-GlcNAc levels from continued hyperglycemic glucose stress. After completing division monocytes/macrophages are recruited to remove this monocyte-adhesive matrix in heparin treated diabetic rats. The receptor involved recognizes a motif on the non-reducing terminal GlcNS-O-S trisaccharide region exposed by heparanase in endosomal compartments involved in forming storage granules in mast cells and in the pathway for catabolizing cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Notably, it has been reported that cell surface localization of heparanase on macrophages can regulate degradation of extracellular matrix heparan sulfate [17], which could provide bio-active heparan sulfate fragments that participate in cell responses of dividing cells.

In addition to kidney mesangial cells [5], bone marrow stromal cells [18] that divide in hyperglycemic medium also initiate the intracellular hyaluronan synthesis and subsequent autophagy responses, which heparin prevented. Further, both daughter cells divert to adipogenesis with production of a monocyte-adhesive extracellular hyaluronan matrix. This appears to occur in the diabetic mouse model in which adipocytes in adipose tissue have a surrounding extracellular hyaluronan matrix with embedded macrophages [19]. Consistent with these results, the adipose tissue from obese mice in this model has limited numbers of osteogenic stem cells compared to adipose tissue from control mice [20]. This latter study showed that adipose from a type 2 diabetic mouse model also had depleted numbers of stem cells, which suggests that the mechanisms outlined above contribute to diabetic complications. In addition, a previous study with dividing aortic smooth muscle cells also showed accumulation of intracellular hyaluronan that was thought to be related to uptake of pericellular hyaluronan matrix [21]. However, this response is consistent with our model because the standard conditions used for this model include growth in hyperglycemic medium. Therefore, we predict that this pathological mechanism will occur in most hyperglycemic dividing cells in vitro and often in vivo, and that it will be a central mechanism involved in many diabetic pathologies and obesity. Finally, understanding the complex cellular mechanisms by which heparin prevents it may help identify therapeutical directions to address diabetic pathologies.

Highlights.

Heparanase cleavage exposes a cryptic binding motif on heparin and heparan sulfate

Putative receptors on dividing cells recognize this motif

This interaction prevents intracellular hyaluronan synthesis in hyperglycemic dividing cells

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants P01 HL 107147 (VCH) and P01 HL 107152 (URD).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

For details on modeling of NS/NA domains, contact Umesh R. Desai urdesai@vcu.edu

References

- 1.Hascall VC, Wang A, Tammi M, Oikari S, Tammi R, Passi A, Vigetti D, Hanson RW & Hart GW (2014). The dynamic metabolism of hyaluronan regulates the cytosolic concentration of UDP-GlcNAc. Matrix Biol 35, 14–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vigetti D, Viola M, Karousou E, De Luca G & Passi A (2014). Metabolic control of hyaluronan synthases. Matrix Biol 35, 8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ren J, Hascall VC & Wang A (2009). Cyclin D3 mediates synthesis of a hyaluronan matrix that is adhesive for monocytes in mesangial cells stimulated to divide in hyperglycemic medium. J Biol Chem 284, 16621–16632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang A, de la Motte C, Lauer M & Hascall V (2011). Hyaluronan matrices in pathobiological processes. FEBS J 278, 1412–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang A, Ren J, Wang CP & Hascall VC (2014). Heparin prevents intracellular hyaluronan synthesis and autophagy responses in hyperglycemic dividing mesangial cells and activates synthesis of an extensive extracellular monocyte-adhesive hyaluronan matrix after completing cell division. J Biol Chem 289, 9418–9429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gambaro G, Cavazzana AO, Luzi P, Piccoli A, Borsatti A, Crepaldi G, Marchi E, Venturini AP & Baggio B (1992). Glycosaminoglycans prevent morphological renal alterations and albuminuria in diabetic rats. Kidney Int. 42, 285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gambaro G, Venturini AP, Noonan DM, Fries W, Re G, Garbisa S, Milanesi C, Pesarini A, Borsatti A, Marchi E & Baggio B (1994). Treatment with a glycosaminoglycan formulation ameliorates experimental diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 46, 797–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wight TN, Heinegard DK & Hascall VC (1991). Proteoglycans: structure and function, in: Hay E, Olsen B (Eds.), Cell Biology of the Extracellular Matrix, 2nd ed. Plenum Press, pp. 45–78. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okada Y, Yamada S, Toyoshima M, Dong J, Nakajima M & Sugahara K (2002). Structural recognition by recombinant human heparanase that plays critical roles in tumor metastasis. Hierarchical sulfate groups with different effects and the essential target disulfated trisaccharide sequence. J Biol Chem 277, 42488–42495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sankaranarayanan NV & Desai UR, (2014). Toward a robust computational screening strategy for identifying glycosaminoglycan sequences that display high specificity for target proteins. Glycobiology 24, 1323–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yanagishita M & Hascall VC (1992). Cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J Biol Chem 267, 9451–9454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miralem T, Wang A & Templeton DM (1996). Heparin inhibits mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent and - independent c-fos induction in mesangial cells. J. Biol. Chem 271, 17100–17106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang A, Fan MY & Templeton DM (1994). Growth modulation and proteoglycan turnover in cultured mesangial cells. J Cell Physiol 159, 295–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang A, Miralem T & Templeton DM (1999). Heparan sulfate chains with antimitogenic properties arise from mesangial cell-surface proteoglycans. Metabolism 48, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang A & Templeton DM (1996). Inhibition of mitogenesis and c-fos induction in mesangial cells by heparin and heparan sulfates. Kidney Int. 49, 437–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamada S, Yoshida K, Sugiura M, Sugahara K, Khoo KH, Morris HR & Dell A (1993). Structural studies on the bacterial lyase-resistant tetrasaccharides derived from the antithrombin III-binding site of porcine intestinal heparin. J Biol Chem 268, 4780–4787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sasaki N, Higashi N, Taka T, Nakajima M & Irimura T (2004). Cell surface localization of heparanase on macrophages regulates degradation of extracellular matrix heparan sulfate. J Immunol 172, 3830–3835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang A, Midura RJ, Vasanji A, Wang AJ & Hascall VC (2014). Hyperglycemia diverts dividing osteoblastic precursor cells to an adipogenic pathway and induces synthesis of a hyaluronan matrix that is adhesive for monocytes. J Biol Chem 289, 11410–11420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han CY, Subramanian S, Chan CK, Omer M, Chiba T, Wight TN & Chait A (2007). Adipocyte-derived serum amyloid A3 and hyaluronan play a role in monocyte recruitment and adhesion. Diabetes 56, 2260–2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rennert RC, Sorkin M, Januszyk M, Duscher D, Kosaraju R, Chung MT, Lennon J, Radiya-Dixit A, Raghvendra S, Maan ZN, Hu MS, Rajadas J, Rodrigues M & Gurtner GC (2014). Diabetes impairs the angiogenic potential of adipose-derived stem cells by selectively depleting cellular subpopulations. Stem Cell Res Ther 5, 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evanko SP & Wight TN (1999). Intracellular localization of hyaluronan in proliferating cells. J Histochem Cytochem 47, 1331–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]