Abstract

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is characterized by cycles of active disease flare and inactive disease remission. During UC remission, IL-22 is upregulated, acting as a hallmark of entrance into UC remission. Recently, we found that in our mouse model of binge alcohol and DSS-induced colitis, alcohol increases severity of UC pathology. In this study, we assessed not only whether alcohol influenced IL-22 expression and thereby perpetuates UC, but also whether recombinant IL-22 (rIL-22) or treatment with a probiotic could alleviate exacerbated symptoms of UC. Levels of large intestine IL-22 were significantly decreased ~6.9 fold in DSS Ethanol compared to DSS Vehicle. Examination of lamina propria (LP) cells in the large intestine revealed IL-22+ γ T cells in DSS Vehicle treated mice were significantly increased, while IL-22+ γδ T cells in DSS Ethanol mice were unable to mount this IL-22 response. We administered rIL-22 and found it restored weight loss of DSS Ethanol treated mice. Colonic shortening and increased Enterobacteriaceae were also attenuated. Administration of Lactobacillus delbrueckii attenuated weight loss (p<0.01), colon length (p<0.001), mitigated increases in Enterobacteriaceae, increased levels of IL-22, and increased levels of p-STAT3 back to that of DSS Vehicle group in DSS Ethanol mice. In contrast, sole administration of Lactobacillus delbrueckii supernatant was not sufficient to reduce UC exacerbation following alcohol. Our findings suggest Lactobacillus delbrueckii contributes to repair mechanisms by increasing levels of IL-22, resulting in phosphorylation of STAT3, thus attenuating the alcohol induced increases in intestinal damage after colitis.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an idiopathic gastrointestinal disease of chronic inflammation that disrupts the structure and function of the gastrointestinal tract. IBD encompasses a multitude of GI inflammatory conditions, but the two most prevalent are Crohn’s Disease (CD) and Ulcerative Colitis (UC)1. CD affects the entirety of the GI tract, while UC is restricted to the colon with inflammation emanating from the rectum and can progress distally to affect the entire colon. The pathogenesis of UC can be explained in part by the presence of a microbial dysbiosis and an abnormal immune response to the dysbiosis, ultimately adversely affecting intestinal health 2. The altered microbial composition changes the balance and activation of T regulatory cells (Treg) and T helper cells (Th) cells in the lamina propria which can precipitate episodes of inflammation, known as a UC flare3,4. UC cycles between these flares and periods of asymptomatic disease. A recent series of clinical studies show that complete regeneration of the intestinal mucosa, called “mucosal healing”, predicts long-term remission and low risk of surgical treatment in IBD patients5.

Interleukin (IL)-22 is a key cytokine that links intestinal immune activation to epithelial repair and barrier protection following damage6,7. IL-22 is expressed by numerous immune cells, including T helper cells, γδ T cells, type 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3), natural killer (NK) cells, and neutrophils. Mice that lack the ability to produce IL-22 following administration of dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) or Citrobacter rodentium are grossly unable to repair barrier damage or control pathogenic bacterial expansion8–10. These data suggest that IL-22 plays a major function in mucosal barrier defense and repair mechanisms, yet treatment of UC focuses on keeping patients in the remission state via combination therapies involving anti-inflammatory drugs like Mesalazine (5-ASA), corticosteroids, or various other biologics11,12.

Interestingly, increased intestinal levels of IL-22 are linked to UC remission. Intestinal epithelial cells express the IL-22 receptor complex and binding of IL-22 results in the induction of mucins, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), and anti-apoptotic pathways that collectively aid in limiting bacterial encroachment while promoting epithelial proliferation, wound healing, and repair13,14. IL-22 protects the intestinal barrier by promoting mucin production, epithelial cell proliferation, and anti-microbial peptide secretion (e.g. Reg3β/Reg3γ)14. Downstream signaling is limited to epithelial cells as the IL-22 receptor, IL-22R1, is only expressed on cells of non-hematopoietic origin15. The primary producers of IL-22 in the intestine are ILC-3, and T-helper (Th)-17 and Th-22 cells that reside in gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT)16. One way IL-22 mediates its protective effects is through the Janus kinase (Jak)/STAT pathways16. The activation of STAT3 via phosphorylation has been shown to be sufficient for IL-22 mediated protection in a variety of systems, including alcoholic liver disease, hepatitis, and graft-versus-host disease17–19.

UC treatments are associated with numerous side effects and discomfort and have yet to be studied in the context of binge alcohol. The goal of this study was to first examine the role of IL-22 following binge alcohol treatment and DSS-induced colitis and secondly, determine whether administration of exogenous IL-22 could alleviate the alcohol induced exacerbation of UC symptoms we have previously observed. Additionally, the probiotic, Lactobacillus delbrueckii sp. bulgaricus, has recently been shown to activate the transcription factor aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), which can induce expression of IL-2220. Thus, the third goal of this study was to examine whether therapeutic intervention with the probiotic Lactobacillus delbrueckii, modulates alcohol-induced exacerbation of UC symptoms.

In our model of DSS-induced colitis and binge alcohol, the UC-inducing agent, DSS, is removed three days before sacrifice to model entrance into UC remission. Sugimoto, Zenewicz, Monteleone, and others UC researchers have provided evidence that IL-22 protects and inhibits intestinal inflammation in the context of colitis8,13,21. Our results show that DSS Vehicle treated mice can mount the proper IL-22 response within the large intestine to begin repair mechanisms required for UC remission. However, the IL-22 response is disrupted in DSS Ethanol treated mice. Unexpectedly, we found that the potential source of increased IL-22 in the large intestine of DSS Vehicle treated mice is lamina propria γδ T cells, while γδ T cells from mice in the DSS Ethanol group were unable to mount the proper IL-22 response.

We further assessed whether administration of rIL-22 would mitigate alcohol-induced exacerbation of DSS colitis. We hypothesized that rIL-22 treatment and/or upregulation of IL-22 by Lactobacillus delbrueckii would protect DSS Ethanol treated mice against the increased symptoms associated with UC. We found that both rIL-22 and Lactobacillus delbrueckii produced protective effects following alcohol consumption and DSS colitis, and that Lactobacillus delbrueckii utilized the IL-22/STAT3 signaling pathway to do so.

Materials and Methods

Induction of DSS Colitis and Binge Alcohol.

Male 8–9 week old (~23–25g body weight) C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). As described previously22,23 mice in DSS group received 2% (wt/vol) DSS (40,000 kDa; MP Biomedicals), ad libitum, in their drinking water for five days. Mice in the Sham group received water only for 5 days acting as a control. On day 5, DSS was discontinued and replaced with normal drinking water in all groups. On day 5, mice in both the DSS and Sham/control group were further subdivided into two subgroups: mice gavaged with ethanol (~3g/kg) or mice gavaged with water on days 5, 6, and 7 to mimic a binge alcohol abuse pattern. The amount of DSS water consumed per animal was recorded and no differences in intake between groups were observed. Mice were weighed every day for the determination of percent weight change. This was calculated as: % weight change = (weight at day X- weight at day 0/weight at day 0) × 100. Animals were monitored clinically for rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and general signs of morbidity, including hunched posture and failure to groom.

Recombinant IL-22 (rIL-22) Treatment.

Mice were subjected to the DSS-induced colitis and binge alcohol paradigm as described above. On day 5, mice were further divided into two subgroups: mice receiving rIL-22 at 1mg/kg (GenScript, Piscataway Township, NJ) via intraperitoneal injection or mice receiving PBS on days 5 and 6. This resulted in four experimental groups: DSS Vehicle, DSS Ethanol, DSS Vehicle + rIL-22, and DSS Ethanol + rIL-22.

Lactobacillus delbrueckii (Lacto) Treatment.

Lactobacillus delbrueckii, sp. bulgaricus OLL1181 (ATCC) was used for all Lacto treatments24,25. On day four, mice were further divided into two subgroups: mice gavaged with 1 × 1011 CFUs of Lacto suspended in 300 mL of PBS or 300 mL of PBS alone on days 4, 5, and 6. This resulted in four experimental groups: DSS Vehicle, DSS Ethanol, DSS Vehicle + Lacto, and DSS Ethanol + Lacto.

Colon Length.

Immediately following euthanasia, colons were excised and length measured from rectum to attachment of the cecum.

Lamina Propria Cell Isolation from Colons.

Lamina propria (LP) cells were isolated as described previously26–29. Three hours after the last gavage on day 7, mice were euthanized and the abdominal cavity was exposed via midline incision. Colons were opened longitudinally, cut into 4–5 cm pieces, washed in cold PBS, and incubated in HBSS supplemented with 10mMol/L HEPES, 50μg/ml gentamicin and 100U/ml penicillin with 100μg/ml streptomycin, 5mM EDTA and 1mM DTT (predigestion solution) for 20 min at 37°C with agitation to remove epithelial cells. Large intestine tissues were cut into small pieces and incubated in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 2mMol/L L-glutamine, 10mMol/L HEPES, 50μg/ml gentamicin, 100U/ml penicillin, 100μg/ml streptomycin, 10% FCS, 0.5mg/ml Collagenae D (Roche), 200 units/ml DNAse I (Sigma- Aldrich), and 0.5mg/ml Dispase II (Roche) (digestion solution) for 20 min. at 37°C with shaking, repeated 2–3 times. The digested tissue was passed through 70 μM cell strainer and centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 10 min at 20°C. Cells (1×106) were stimulated with Cell Stimulation Cocktail (plus protein transport inhibitors), which contains Phorbol 12-Myristate 13-Acetate (PMA), Ionomycin, Brefeldin A and Monensin, in cell culture medium for 3 h.

Fluorescence Activated Cell-Sorting (FACS).

For the measurement of large intestine T cell, innate lymphoid cell 3, and neutrophil cell populations, mixed cells were re-suspended in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (phosphate buffered saline with 5% fetal bovine serum) at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL. Cell suspensions were blocked with purified antimouse CD16/32 for 20 minutes at 4°C and stained with live/dead PacOrange dye to separate live cell populations. Isolated cells were further stained with PerCP – Cy5.5 conjugated antimouse CD3, APC eFluor 780 - conjugated antimouse CD4, APC-conjugated antimouse NKp46, PE Cy7 conjugated – antimouse GR1, FITC – conjugated antimouse γδ TCR and PE-conjugated antimouse IL-22 for 30 minutes in the dark at 4°C. Intracellular staining of IL-22 was performed using BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Fixation/Permeabilization Kit according to the manufacture’s instruction. The cells were washed twice and resuspended in 0.5-mL FACS buffer. All samples were analyzed at the Loyola University Health Sciences Division FACS Core Facility using a 7-color flow cytometer (BD FACSCanto II) and FlowJo Software (Treestar).

Quantitative Analyses of Fecal Enterobacteriaceae and Lactobacillus.

Real-time PCR was used to quantify bacterial ribosomal small subunit (SSU) 16S rRNA gene abundance, as described previously23,30. Primers targeting SSU rRNA genes of microorganisms at the domain level (Bacteria), phylum level (Gammaproteobacteria), and at the family level (Enterobacteriaceae and Lactobacillus) were used. Primers included F: (ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAGT) and R: (ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGGC) for domain-level analyses, F: (TCGTCAGCTCGTGTYGTGA) and R: (CGTAAGGGCCATGATG) for Gammaproteobacteria, and F: (GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA) and R: (GCCTCAAGGGCACAACCTCCAAG) for Enterobacteriaceae and F: (AGCAGTAGGGAATCTTCCA) and R: (CACCGCTACACATGGAG) for Lactobacillus (Thermo Fisher Scientific). 10-fold dilution standards were made from purified genomic DNA from reference bacteria. Reactions were run at 95°C for 3’, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15” and a 63°C (Bacteria) or 67°C (Enterobacteriaceae) for 60” using a Step One Plus Real-Time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). To interpret bacterial DNA relative quantity (RQ), Ct values from target bacteria (Enterobacteriaceae or Lactobacillus) were normalized to total bacteria Ct values to obtain a relative copy # quantity of the target bacteria to that of total bacteria.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay.

Mice in all four groups were sacrificed three hours after the last gavage on day 7. Large intestines were harvested and homogenized. The homogenates were analyzed for IL-22 (eBioscience) and IL-17 (R&D Systems) using their respective ELISAs per the manufacturer’s instructions. The cytokine levels were expressed pg per milligram of total protein in the homogenates.

Western Blot.

Following sacrifice after the last gavage on day 7, large intestines were homogenized. Homogenates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and were transferred to either PVDF or nitrocellulose membranes. The membrane was blocked for 1 hour at room temperature with 5% BSA in TBS-T (0.05% Tween 20 in TBS). Following this, the membrane was incubated with a desired antibody (e.g., anti-STAT3, Cell Signaling Technology, anti-pSTAT3, Cell Signaling Technology, or anti-β-actin, Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4°C. Membranes were washed with TBS-T and incubated with secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase for one hour. After the incubation in the secondary antibody, the membrane was washed five times for five minutes in TBS-T and one time for 10 minutes in TBS. Following the final wash, the membranes were probed using Western Lightning™ Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (PerkinElmer, Norwalk, CT). The membrane was visualized using a BioRad ChemiDoc System.

Statistics.

Comparisons within groups were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with a Tukey post-hoc test. Analysis was done using GraphPad Prism software. A confidence level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Significance is represented as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Results

In this study, we assessed whether alcohol influenced IL-22 expression and thereby perpetuates UC. To accomplish this, mice were divided into two groups: DSS and Sham. In DSS group, mice received 2% DSS ad libitum in their drinking water for 5 days to induce UC. Mice in Sham/control group received water. On day 5, DSS was removed from the drinking water to mimic entrance into remission. Additionally on day 5, DSS and Sham/control group mice were further subdivided into two subgroups: mice gavaged with alcohol (~3g/kg) or mice gavaged with water days 5, 6, and 7. Three hours after the last gavage on day 7 colons were harvested and processed for quantification IL-22. As seen in Figure 1A, DSS Vehicle treated mice had elevated levels of IL-22 in large intestine homogenates, an indicator of entrance into UC remission. By contrast, mice in the DSS Ethanol group show decreased levels of IL-22 compared to DSS Vehicle, highlighting the continuance of UC symptoms and inability to enter into UC remission.

Figure 1. IL-22 Levels After Alcohol Consumption in DSS-Induced Colitis.

A. Elevated Levels of IL-22 in DSS Vehicle but Not DSS Ethanol Treated Mice. Values are mean ± SEM 3–5 animals per group. *p<0.05 DSS Vehicle compared to all other groups by two-way ANOVA. B. Binge Alcohol Consumption Following DSS-Induced Colitis Decreases the Percentage of IL-22+ cells in Large Intestine Lamina Propria. Values are mean ± SEM 2–6 animals per group. *p<0.05 DSS Ethanol compared to Sham Vehicle by two-way ANOVA.

Multiple immune cells within the large intestine lamina propria are capable of producing IL-22, such as T cells, innate lymphoid cells, and neutrophils. We next sought to determine what specific cells were responsible for the elevated levels of IL-22 we observed in DSS Vehicle mice, and, furthermore, what cell population or populations were impaired in their ability to produce IL-22 following administration of both DSS and Ethanol. To accomplish this, large intestine lamina propria cells were isolated and analyzed by FACS. Figure 1B demonstrates that the percentage of IL-22+ cells in the large intestine lamina propria in DSS Ethanol treated mice is significantly reduced compared to Sham Vehicle. There is a downward trend of decreased IL-22+ cells in DSS Ethanol compared to DSS Vehicle, but it did not reach significance. When large intestine LP lymphoid cells were sorted into CD3+CD4+ T cells, we did not find any difference in their percentage in DSS Ethanol group compared to other DSS Vehicle or Sham mice. However, when CD3+CD4+ T cells were also gated for IL-22+, the percentage of CD3+CD4+IL-22+ T cells was significantly decreased in both DSS treated groups, but not significantly different between Vehicle and Ethanol, Figure 2.

Figure 2. DSS-Induced Colitis Decreases the Percentage of CD3+CD4+IL-22+ T Cells.

A. and B. Representative two color FACs plots of A. CD+CD4+ T cells and B. CD3+CD4+ T cells gated for IL-22+. C. Summary of percentage of CD3+CD4+ T cells in the large intestine LP. D. Summary of percentage of CD3+CD4+IL-22+ T cells in the large intestine LP. Values are mean ± SEM 5–12 animals per group. *p<0.05 Sham Ethanol compared to Sham Vehicle; ****p<0.0001 DSS Vehicle and DSS Ethanol compared to Sham Vehicle by two-way ANOVA.

Next, we examined a population of type 3 innate lymphoid cells in their ability to express IL-22, as ILC3s have been implicated in the pathogenesis of UC. We gated on live CD3−CD4− lymphocytes, then utilized the cell surface marker NKp46 to differentiate ILC3s, which are NKp46+. Similar to what other researchers have observed, there was a decrease in the percentage of IL-22+ ILC3s following DSS-induced colitis. However, Figure 3 demonstrates that in our model of binge alcohol consumption after DSS-induced colitis there was no difference in large intestine ILC3s’ ability to produce IL-22 after receiving alcohol compared to vehicle treated mice. Another cell type known not only to be involved in the pathogenesis of UC, but also involved in IL-22 production is neutrophils. Therefore, we stained our isolated large intestine LP cells with a common neutrophil marker GR1 and examined the percentage of neutrophils also expressing IL-22. We found a significant increase in the percentage of neutrophils in the large intestine LP following DSS-induced colitis, but there was no difference with the addition of alcohol. Furthermore, the percentage of IL-22+ neutrophils was significantly decreased in the large intestine LP following DSS-induced colitis compared to shams but this was also not found to be significantly different between the DSS Vehicle and DSS Ethanol treated mice, Figure 4. Finally, we assessed γδ T cells, a population of T cells with a distinct T cell receptor (TCR) and known to produce IL-22. Figure 5 shows that the percentage of γδ T cells in the large intestine lamina propria increase in both DSS Vehicle and DSS Ethanol treated mice, but we did not observe any further increase with the addition of alcohol. Interestingly, the percentage of IL-22+ γδ T cells was significantly increased in DSS Vehicle treated mice compared to both Sham Vehicle and Sham Ethanol, which mimics our results of IL-22 levels in large intestine homogenates in Figure 1A. Furthermore, this increase in IL-22+ γδ T cells was decreased in the DSS Ethanol group compared to DSS Vehicle. These data give evidence to the fact that the alcohol induced reduction in large intestine IL-22 following DSS-induced colitis could be attributed to an inability of γδ T cells to mount a proper IL-22 response when alcohol is present, thus exacerbating an UC pathology.

Figure 3. No Difference in Percentage of CD3−NKp46+IL-22+ ILC3s Between Vehicle and Ethanol Treated Mice.

A. and B. Representative two color FACs plots of A. CD-CD4− lymphocytes to sort ILC3s and B. CD3−CD4− lymphocytes were further gated on the ILC3 marker NKp46 and also IL-22. C. Summary of percentage of CD3−CD4−NKp46+IL-22+ ILC3s in the large intestine LP. Values are mean ± SEM 5–11 animals per group. *p<0.05 DSS Ethanol compared to Sham Vehicle by two-way ANOVA.

Figure 4. No Difference in Percentage of GR1+IL-22+ Neutrophils After Alcohol Consumption in DSS-Induced Colitis.

A. and B. Representative two color FACs plots of A. Large intestine LP lymphocytes were further gated on neutrophil marker GR1. B. GR1+ cells were further gated on IL-22 to determine percentage of GR1+IL-22+ neutrophils in the large intestine lamina propria. C. Summary of % GR1+ neutrophils in the large intestine LP. Values are mean ± SEM 5 animals per group. **p<0.001 DSS Vehicle vs. Sham Vehicle and Sham Ethanol; ***p<0.001 DSS Ethanol vs. Sham Vehicle and Sham Ethanol by two-way ANOVA. D. Summary of % GR1+IL-22+ neutrophils in the large intestine LP. Values are mean ± SEM 5 animals per group. *p<0.05 DSS Vehicle vs. Sham Ethanol; **p<0.01 DSS Ethanol vs. Sham Ethanol by two-way ANOVA.

Figure 5. The Percentage of IL-22+ γδ T Cells Significantly Increased After DSS-Induced Colitis, but Following Binge Alcohol this Increase Was Impaired.

A. and B. Representative two color FACs plots of %γδ T cells. A. Large intestine LP lymphocytes were further gated on γδTCR. Values are mean ± SEM 5 animals per group. **p<0.01 DSS Vehicle vs. Sham Ethanol; ***p<0.001 DSS Vehicle vs. Sham Vehicle ***p<0.001 DSS Ethanol Sham Ethanol by two-way ANOVA. ****p<0.0001 DSS Ethanol vs. Sham Ethanol % IL-22+ γδ T cells. Values are mean ± SEM 5 animals per group. *p<0.05 DSS Vehicle vs. Sham Vehicle and Sham Ethanol by two-way ANOVA.

Alcohol’s role in diminishing the IL-22 response needed for entrance into UC remission could explain the exacerbated UC symptoms we have previously observed. IL-22 protects and inhibits intestinal inflammation in the context of colitis. Therefore, we treated mice with rIL-22 (Figure 6) and examined the effect of rIL-22 treatment on the two most common assessments of UC severity in mouse models – weight loss and colon length. Figure 6B shows that DSS Ethanol treated mice repeatedly loose significantly more weight than DSS Vehicle mice, ~12.5% vs. ~6%, respectively. However, the average weight loss in DSS Ethanol mice treated with rIL-22 on days 5 and 6 was similar to that of DSS Vehicle on day 7, ~6%. As we have previously observed, Figure 6C shows that our binge alcohol paradigm after DSS-induced colitis significantly decreases colon length. Treatment with rIL-22 in the DSS Ethanol +rIL-22 reverted colonic shortening back to levels of DSS Vehicle treated mice.

Figure 6. rIL-22 Treatment Prevented the Alcohol Induced Increase in Weight Loss and Colonic Shortening Following DSS-Induced Colitis.

A. Model of Treatment with rIL-22 in the Context of DSS-Induced Colitis and Binge Alcohol. B. Percent Weight Change of Animals. Determined by the following equation: % weight change = (weight at day X-weight at day 0/weight at day 0)*100. Values are mean ± SEM 4–12 animals per group. By two-way ANOVA on day 7 with Tukey post-hoc *p<0.05 DSS Ethanol vs. DSS Vehicle; p=0.07 DSS Ethanol vs. DSS Ethanol + rIL-22. ***p<0.001 DSS Ethanol vs DSS Vehicle +rIL-22. C. Colon Length Measured in Centimeters (cm) on Day 7. Values are means ± SEM, n=4–12 animals/group. *p<0.05 DSS Ethanol vs. DSS Vehicle; **p<0.01 DSS Ethanol vs DSS Vehicle + rIL-22; *p<0.05 DSS Ethanol vs DSS Ethanol + rIL-22 by two-way ANOVA with Tukey Post-hoc.

Alterations of the large intestine microbiome are commonly associated with severity of UC pathogenicity. Our lab has previously observed increases in Enterobacteriaceae, a pathogenic family of bacteria, and decreases in Lactobacillus, a potentially beneficial family of bacteria, following DSS-induced colitis and alcohol. Therefore, we performed quantitative real-time PCR on 16S ribosomal RNA of Enterobacteriaceae and Lactobacillus on large intestine luminal contents to determine whether treatment with rIL-22 could prevent the microbial changes we observed in our model of binge alcohol and colitis. Copies of Total Bacteria within the large intestine luminal content via qRT-PCR analysis were used for normalization. In line with our previous results22,23, DSS Ethanol treated mice have a large increase in Enterobacteriaceae (~4 fold) on day 7 compared to DSS Vehicle treated mice. rIL-22 treatment not only reduced the Enterobacteriaceae copy number in the DSS Vehicle group, but also dramatically reduced Enterobacteriaceae copy number in the DSS Ethanol group back to that of DSS Vehicle + PBS, Figure 7A. Copy number of Lactobacillus was decreased ~1 fold in DSS Ethanol mice compared to DSS Vehicle. Treatment with rIL-22 was able to partially restore Lactobacillus copy number, but it was not back to the level of DSS Vehicle, Figure 7B.

Figure 7. rIL-22 Prevents Overgrowth of Gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae and Partially Restores Lactobacillus Copy Numbers Following Alcohol and Colitis.

Real-time PCR 16S rRNA sequencing of large intestine luminal content with primers specific for A. Enterobacteriaceae *p<0.05 DSS Ethanol vs DSS Vehicle + rIL-22 by two-way ANOVA B. Lactobacillus. Values are mean ± SEM 4–12 animals per group.

Taken together, these data support our hypothesis that IL-22 promotes intestine health and mitigates microbial dysbiosis following binge alcohol and DSS colitis. Although we observed beneficial effects with administration of recombinant IL-22, treatment of UC patients with a recombinant protein is not the most viable option due to potentially detrimental systemic side effects.

Probiotics are widely used and are available without a prescription. Therefore, we sought to understand whether treatment with Lactobacillus delbrueckii, a bacteria commonly found in over the counter probiotics could provide protective effects following binge alcohol and UC. For these studies, we utilized our established model of 2% DSS in the drinking water of mice followed by a three-day binge alcohol paradigm or water for control. However, on day 4 mice were further subdivided into mice receiving 1×1011 CFUs of Lactobacillus delbrueckii on the evenings of day 4, 5, and 6, Figure 8A. This resulted in four overall experimental groups – DSS Vehicle, DSS Ethanol, DSS Vehicle +Lacto, and DSS Ethanol +Lacto.

Figure 8. Treatment with Lactobacillus delbrueckii Attenuated the Alcohol Induced Increases in Weight Loss and Colonic Shortening Following DSS Colitis.

A. Model of Treatment with Lactobacillus delbrueckii in the Context of DSS-Induced Colitis and Binge Alcohol. B. Percent weight change of animals was determined by the following equation: % weight change = (weight at day X-weight at day 0/weight at day 0)*100. Values are mean ± SEM n = 6–8 animals per group. *p<0.05 DSS Ethanol vs. DSS Vehicle; *p<0.05 DSS Ethanol vs DSS Ethanol + Lacto; ****p<0.0001 DSS Ethanol vs DSS Vehicle + Lacto; *p<0.05 DSS Ethanol + Lacto vs. DSS Vehicle + Lacto by two-way ANOVA on day 7 with Tukey post-hoc. C. Colon length measured in centimeters (cm) on day 7. Values are means ± SEM, n=6–8 animals/group. *p<0.05 DSS Ethanol compared to DSS Vehicle by student’s test; ***p<0.01 DSS Vehicle + Lacto compared to DSS Ethanol; ****p<0.001 DSS Ethanol + Lacto compared to DSS Ethanol by two-way ANOVA with Tukey Post-hoc.

In line with ours and other’s previous reports, mice in both the DSS Vehicle and DSS Ethanol groups began losing weight on day 5 as is expected with the UC disease being induced by DSS. Furthermore, mice in the DSS Ethanol group lost significantly more weight compared to DSS alone, ~8% vs. ~4.5%, respectively; a consistent finding in our lab with the addition of ethanol to DSS treated mice. Interestingly, treatment with Lactobacillus delbrueckii not only mitigated weight loss in DSS vehicle (~2% body weight loss in DSS Vehicle + Lacto group vs. ~4.5% loss in DSS Vehicle mice), but it also attenuated weight loss in the DSS Ethanol treated mice, which is demonstrated by the DSS Ethanol + Lacto group’s average weight loss being similar to that of DSS Vehicle on day 7 (Figure 8B). Colon length was also improved with Lactobacillus delbrueckii treatment Figure 8C shows that mice in the DSS Ethanol treatment group again experienced significant increases in colonic shortening compared to DSS Vehicle mice. However, when DSS Ethanol mice were given Lacto, their colon length was equivalent to that of DSS Vehicle.

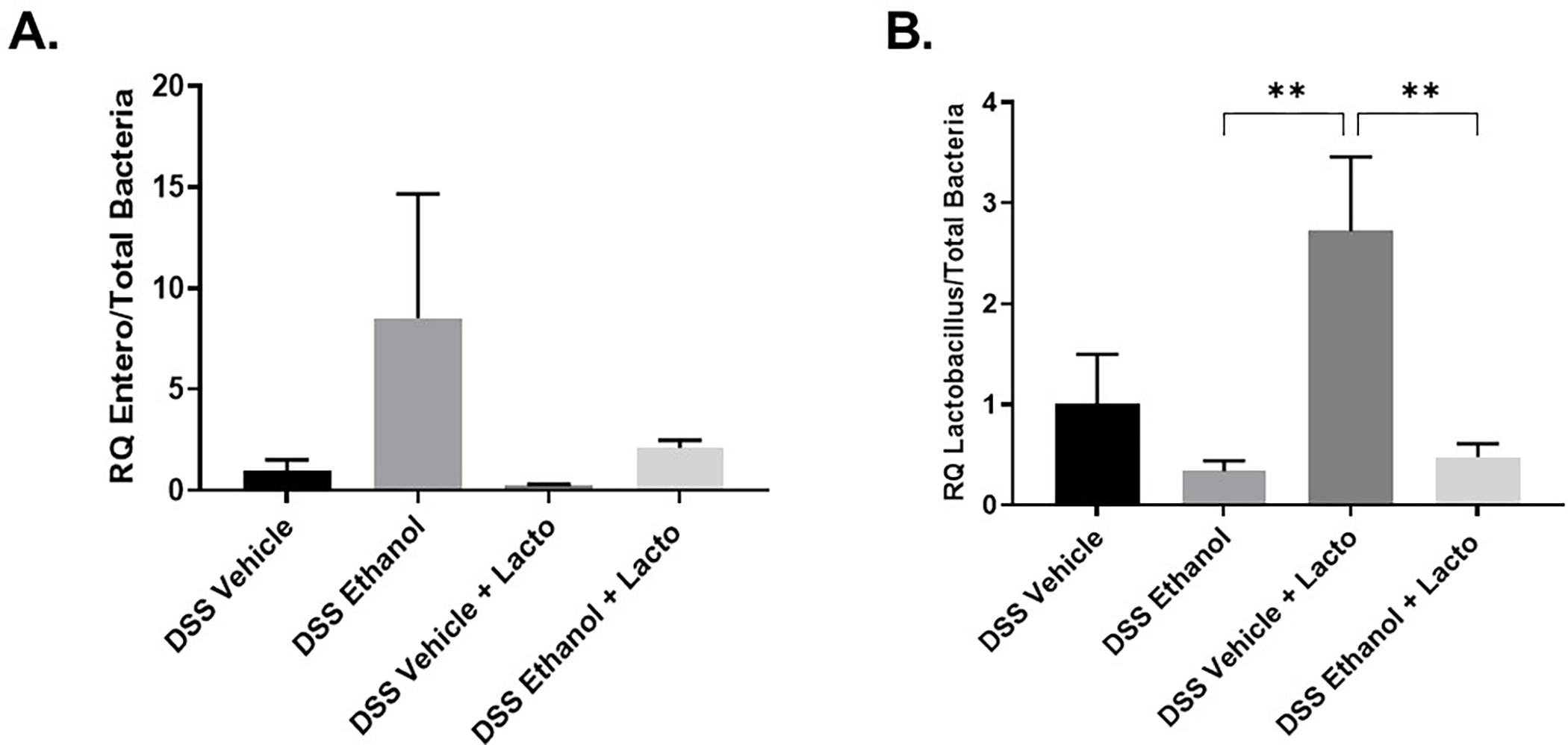

Secondly, we sought to determine whether treatment with the probiotic, Lactobacillus delbrueckii, could also normalize aspects of the dysbiosis our lab has observed following DSS-induced colitis and binge alcohol consumption. We again performed quantitative real-time PCR on 16S ribosomal RNA of Enterobacteriaceae and Lactobacillus on large intestine luminal content with copies of Total Bacteria used for normalization. Our results showed a large 7.5 – fold increase in Enterobacteriaceae in DSS Ethanol mice compared to DSS Vehicle. However, as can be seen in Figure 9A, the large increase in Enterobacteriaceae seen in the DSS Ethanol group was impressively reduced to the levels of DSS Vehicle when DSS Ethanol mice were treated with Lacto. Figure 9B shows that copies of Lactobacillus were decreased in DSS Ethanol compared to DSS Vehicle. Interestingly, when both groups were treated with Lacto, copies of Lactobacillus drastically increased in DSS Vehicle mice, but not DSS Ethanol. Therefore, our data supports the hypothesis that treatment with Lactobacillus delbrueckii is able to modulate the alcohol-induced exacerbation of UC symptoms we see in our model of DSS-colitis and binge alcohol.

Figure 9. Lactobacillus delbrueckii Prevents Overgrowth of Gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae.

Real-time PCR 16S rRNA sequencing of large intestine luminal content with primers specific for A. Enterobacteriaceae B. Lactobacillus, **p<0.01 DSS Vehicle + Lacto compared to DSS Ethanol and DSS Ethanol + Lacto by two-way ANOVA with Tukey Post-hoc. Values are mean ± SEM n = 6–8 animals per group.

Next, we wanted to elucidate the potential mechanism by which Lactobacillus delbrueckii provided these protective effects following UC and binge alcohol. As treatment with Lactobacillus delbrueckii has been shown to increase levels of IL-22, we assessed levels of large intestine IL-22. Consistent with our previous findings, levels of IL-22 in DSS Ethanol mice compared to DSS Vehicle were significantly decreased. In the DSS Ethanol + Lacto group, Lacto treatment was able to increase levels of IL-22, though not back to levels of DSS Vehicle, Figure 10A. As the cytokines IL-22 and IL-17 are so closely related, with IL-22 regarded as anti-inflammatory and IL-17 as pro-inflammatory, we also measured levels of colonic IL-17. Treatment with Lacto in the DSS Ethanol group was able to reduce large intestine levels of IL-17 compared to DSS Vehicle, but not compared to DSS Ethanol, Figure 10B.

Figure 10. Lactobacillus delbrueckii Treatment Trended Towards an Increase in Large Intestine Levels of IL-22, but Did Not Decrease Levels of IL-17.

A. Levels of total large intestine IL-22 quantified by ELISA. Values are mean ± SEM 6–8 animals per group. p=0.056 DSS Ethanol vs. DSS Vehicle by two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc. *p<0.05 DSS Ethanol vs. DSS Ethanol + Lacto by student’s t-test. B. Levels of total large intestine IL-17 quantified by ELISA. Values are mean ± SEM 6–8 animals per group. *p<0.05 DSS Ethanol + Lacto vs. DSS Vehicle by ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc.

The protective effects of IL-22 are mediated in part through the phosphorylation and activation of the transcription factor, STAT3. Phosphorylation of STAT3 allows for upregulation of genes involved in the production of AMPs and the intestinal healing process. Therefore, we measured levels of both STAT3 and pSTAT3 in large intestine homogenates following treatment with Lactobacillus delbrueckii. Figure 11 shows that large intestine levels of pSTAT3 in DSS Ethanol mice are significantly decreased compared to that of DSS Vehicle. Interestingly, when DSS Ethanol mice were treated with Lacto, levels of pSTAT3 increased back to that of DSS Vehicle.

Figure 11. Treatment with Lactobacillus delbrueckii Attenuates Decreased Levels of pSTAT3 in DSS Ethanol Mice.

Protein isolated from total large intestine tissue was probed for STAT3 and pSTAT3 (Y705) by representative Western blot. Densiometric analysis was performed to express the ratio of pSTAT3/β-actin. *p<0.05 DSS Ethanol compared to DSS Vehicle by two-way ANOVA. Values are mean ± SEM 4–6 animals per group.

Finally, we wanted to answer the question of whether the beneficial effects we observed following treatment with Lactobacillus delbrueckii was due to the bacteria itself or a potential factor released by the bacteria. As can be seen in Figure 12A and B, in order to reduce weight loss and colonic shortening back to the level of DSS Vehicle treated mice, DSS Ethanol treated mice must receive whole Lacto bacteria. Treatment with Lacto supernatant alone did not prevent the weight loss and colonic shortening in DSS Ethanol group.

Figure 12. Lactobacillus delbrueckii Bacteria are Required to Attenuate the Alcohol Induced Increases in Weight Loss and Colonic Shortening Following DSS Colitis.

A. Percent weight change of animals was determined by the following equation: % weight change = (weight at day X-weight at day 0/weight at day 0)*100. Values are mean ± SEM n = 5 animals per group. **p<0.01 DSS Ethanol vs. DSS Vehicle by; **p<0.01 DSS Ethanol + Lacto Sup. vs DSS Vehicle by two-way ANOVA on day 7 with Tukey post-hoc. B. Colon length measured in centimeters (cm) on day 7. Values are means ± SEM, n=5 animals/group. *p<0.05 DSS Ethanol compared to DSS Vehicle and DSS Ethanol + Lacto bacteria compared to DSS Ethanol + Lacto sup; **p<0.01 DSS Vehicle compared to DSS Ethanol + Lacto sup. by two-way ANOVA with Tukey Post-hoc.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to understand how binge alcohol consumption could be perpetuating UC pathology. The cytokine IL-22 has been found to be a hallmark of entrance into UC remission as it contributes to production of antimicrobial peptides and mucins, regulation of gut microbiota, maintenance of gut barrier function and amelioration of intestinal inflammation31,32. The increased weight loss, colonic shortening, more profound histopathology and clinical scores, and increased intestinal inflammation as we recently observed22 clearly demonstrate alcohol’s role in increasing symptoms of UC.

Combined with the knowledge that IL-22 is a critical cytokine for entrance into UC remission, we examined whether alcohol was affecting IL-22 levels and thus perpetuating UC symptoms. Our results show that mice allowed to recover for 3 days, the DSS Vehicle group, experienced increased levels of IL-22 in large intestine homogenates. In mouse models of colitis, the innate immune response in the colon includes recruited macrophages and neutrophils, which appear to have both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory roles in colitis33. Specifically, aberrant control of these infiltrating neutrophils can result in tissue damage in the colon caused by abundant reactive oxygen species34–36. However, recent studies demonstrated that neutrophils can play a protective role in the host response in acute models of colitis by producing IL-2237,38. Hence, we examined whether the spike in IL-22 levels in DSS Vehicle mice was due to infiltrating neutrophils, and conversely whether the diminished IL-22 response in DSS Ethanol mice was a consequence of abnormal control of IL-22+ producing neutrophils. We found that both large intestines of DSS Vehicle and DSS Ethanol mice had increased percentage of neutrophils. In contrast to Zindl et al.’s results, these isolated neutrophils were not producing IL-22 in our model of DSS-induced colitis and alcohol.

In recent years γδ T cells have emerged as one of the most prominent sources of IL-22 in the intestine and examination of IL-22+ γδ T cells in our model of DSS-induced colitis and binge alcohol revealed that DSS Vehicle treated mice had a significantly increased percentage of IL-22+ γδ T cells. However, this response was abolished in DSS Ethanol treated mice. This balance between decreased percentages of IL-22+ neutrophils and simultaneous decreases in percentages of IL-22+ γδ T cell in DSS Ethanol mice gives evidence to how alcohol could be damaging the critical IL-22 response. This response is needed to restore the integrity of the intestine following mucosal injury by stimulating proliferation, mucous protection, and AMP secretion, thus driving entrance into the remission period from a UC flare38–43.

Therefore, increasing levels of large intestine IL-22 in the context of binge alcohol consumption and UC could act as a potential therapeutic target to improve lives of UC patients. IL-22 remains one of the most intriguing cytokines due to its ability to elicit completely different responses based on the microenvironment. In the context of the intestines, the presence of IL-22 appears to be beneficial under most circumstances including inflammatory bowel disease, graft-versus-host disease, and many types of bacterial infection16,17,44–47. We recognize that patients suffering from UC and mouse models of colitis present with areas of the colon inflamed with ulcers/lesions. Examining lesion vs. non-lesion areas in the context of alcohol-induced exacerbation of colitis for changes in anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-22, is of critical importance. Future studies will focus on understanding how these different areas of the colon affect UC disease progression and/or potential therapeutics.

Interestingly, certain intestinal infections, such as in mouse models using T. gondii, cause IL-22 to be pro-inflammatory48,49. While the reasons behind these differential responses of IL-22 remain unknown, it illuminates the importance of understanding the role of IL-22 under different conditions. In addition, clinical trials using Fc-fusion IL-22 administration for treatment of patients with graft-versus-host disease have shown promising preliminary results, indicating that IL-22 treatment may be efficacious in a clinical setting50. Here, we demonstrated that the alcohol induced exacerbation of UC symptoms including increased weight loss, colonic shortening, and large intestine Enterobacteriaceae copy number can be attenuated by exogenous administration of rIL-22. Although this is an exciting finding for the field of alcohol and colitis research, translating this treatment of an exogenous protein into UC patients could possibly have systemic side effects, making it a less desirable therapeutic candidate. Therefore, we chose to examine therapies that would elicit a similar IL-22 response, while being primarily localized to the intestine.

The rationale for probiotics as a viable treatment option for UC patients is 2-fold. First, as discussed above, UC pathogenesis is tripartite: genetic predisposition, microbial dysbiosis, and overactive intestinal immune system. Damage to the intestinal barrier during UC can permit pathogenic luminal bacteria to initiate a mucosal inflammatory response that never ceases. Probiotic treatment could stabilize the altered bacterial milieu of the gut to allow for proliferation of less pathogenic and more anti-inflammatory bacterial species, which could abrogate mucosal inflammation51,52. The second consideration is that UC is a mucosal disease, so a therapy that works at the level of the mucosa should be beneficial. While antibiotics tend to be most effective in Crohn’s colitis, ileocolitis, and pouchitis, they are less effective in UC53–55, suggesting that inherent deficits in the intestinal bacteria may be the larger issue for UC.

Probiotics have been shown to reduce colitis in animal models56,57 while also having some efficacy in treating acute UC flare and maintaining disease remission in humans58–64. From the perspective of IL-22, Lactobacillus delbrueckii, was recently shown to activate the transcription factor aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), which can induce expression of IL-22. Takamura et al. found that treatment with Lactobacillus delbrueckii in an experimental model of colitis resulted in amelioration of colitis by activating the AhR pathway. Lactobacillus delbrueckii induced the mRNA expression of cytochrome P450 family 1A1 (CYP1A1), a target gene of the AhR pathway, which was inhibited by the addition of an AhR antagonist24,65. These data made Lactobacillus delbrueckii an exciting therapeutic option to determine whether probiotic treatment could potentially reverse increased UC symptoms as a result of alcohol use.

We found that treatment with the probiotic, Lactobacillus delbrueckii, was able to mediate protection against exacerbated UC symptoms of weight loss and colonic shortening following binge alcohol consumption. Furthermore, Lacto treatment reduced levels of the pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae in DSS-colitis and binge alcohol back to that of non-alcohol treated mice. Treatment with Lacto was able to increase levels of IL-22 in the DSS Ethanol + Lacto group, but it was unable to do so in the DSS Vehicle + Lacto group. Potentially Lactobacillus delbrueckii is working through multiple or different mechanisms as levels of pSTAT3 were also increased with Lacto treatment, highlighting a potential mechanism by which this probiotic elicited protective effects against alcohol-induced worsening of UC.

We recognize that multiple probiotics might be needed to maintain UC remission as the probiotic preparation VSL#3, consisting of a mixture of Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium longum, Bifidobacterium infantis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus paracasei, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, and Streptococcus thermophiles, has been reported to be effective in maintenance of remission of UC62. Our future studies with Lactobacillus delbrueckii will focus on not only its protective effects alone, but also how it can be combined into a probiotic cocktail to achieve maximum intestinal repair and protection against alcohol-induced exacerbation of UC. Thus, Lactobacillus delbrueckii treatment provides an exciting a therapeutic option for UC patients experiencing symptom exacerbation and/or prolonged flare due to alcohol use by tipping the scales into a period of remission.

While our current study utilizes mouse body weight and colon length as the indicators of DSS-induced colitis, we plan to expand these observations to colonic inflammation and histological changes in our future studies. Our previously published data showed a good correlation of loss in the colon length and body weight with histological changes and clinical score following DSS and DSS + ethanol23,66.

In summary, our results confirm our previous findings of binge alcohol drinking exacerbating an UC pathology22,23 while highlighting the contribution IL-22+ γδ T cells and the protective role of IL-22 and Lactobacillus delbrueckii to the intestine following the combined insult. Our findings support a probiotic and IL-22 targeted therapeutic intervention for UC patients and those with concomitant alcohol use, which may translate to other pathological conditions involving damage to the intestinal barrier.

Acknowledgements:

The content of this manuscript has been published, in part, as part of the thesis of Abigail Cannon66.

Funding Support:

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R21AA025806, T32AA013527, F30AA027442.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Reference List

- 1.Crohn’s and colitis foundation of america. http://www.ccfa.org/resources/facts-about-inflammatory.html. Updated May, 2011March, 2016.

- 2.Sartor RB. Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(2):577–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maslowski KM, Vieira AT, Ng A, et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature. 2009;461(7268):1282–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ivanov II, Frutos Rde L, Manel N, et al. Specific microbiota direct the differentiation of IL-17-producing T-helper cells in the mucosa of the small intestine. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4(4):337–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neurath MF, Travis SP. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases: A systematic review. Gut. 2012;61(11):1619–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sonnenberg GF, Fouser LA, Artis D. Border patrol: Regulation of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis at barrier surfaces by IL-22. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(5):383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sonnenberg GF, Fouser LA, Artis D. Functional biology of the IL-22-IL-22R pathway in regulating immunity and inflammation at barrier surfaces. Adv Immunol. 2010;107:1–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zenewicz LA, Yancopoulos GD, Valenzuela DM, Murphy AJ, Stevens S, Flavell RA. Innate and adaptive interleukin-22 protects mice from inflammatory bowel disease. Immunity. 2008;29(6):947–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng Y, Valdez PA, Danilenko DM, et al. Interleukin-22 mediates early host defense against attaching and effacing bacterial pathogens. Nat Med. 2008;14(3):282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zindl CL, Lai JF, Lee YK, et al. IL-22-producing neutrophils contribute to antimicrobial defense and restitution of colonic epithelial integrity during colitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(31):12768–12773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanauer SB. Inflammatory bowel disease: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic opportunities. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12 Suppl 1:S3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins PD, Rubin DT, Kaulback K, Schoenfield PS, Kane SV. Systematic review: Impact of non-adherence to 5-aminosalicylic acid products on the frequency and cost of ulcerative colitis flares. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(3):247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sugimoto K, Ogawa A, Mizoguchi E, et al. IL-22 ameliorates intestinal inflammation in a mouse model of ulcerative colitis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(2):534–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizoguchi A Healing of intestinal inflammation by IL-22. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(9):1777–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolk K, Kunz S, Witte E, Friedrich M, Asadullah K, Sabat R. IL-22 increases the innate immunity of tissues. Immunity. 2004;21(2):241–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sabat R, Ouyang W, Wolk K. Therapeutic opportunities of the IL-22-IL-22R1 system. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13(1):21–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ki SH, Park O, Zheng M, et al. Interleukin-22 treatment ameliorates alcoholic liver injury in a murine model of chronic-binge ethanol feeding: Role of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. Hepatology. 2010;52(4):1291–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanash AM, Dudakov JA, Hua G, et al. Interleukin-22 protects intestinal stem cells from immune-mediated tissue damage and regulates sensitivity to graft versus host disease. Immunity. 2012;37(2):339–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radaeva S, Sun R, Pan HN, Hong F, Gao B. Interleukin 22 (IL-22) plays a protective role in T cell-mediated murine hepatitis: IL-22 is a survival factor for hepatocytes via STAT3 activation. Hepatology. 2004;39(5):1332–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takamura T, Harama D, Fukumoto S, et al. Lactobacillus bulgaricus OLL1181 activates the aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway and inhibits colitis. Immunol Cell Biol. 2011;89(7):817–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monteleone I, MacDonald TT, Pallone F, Monteleone G. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor in inflammatory bowel disease: Linking the environment to disease pathogenesis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2012;28(4):310–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cannon AR, Kuprys PV, Cobb AN, et al. Alcohol enhances symptoms and propensity for infection in inflammatory bowel disease patients and a murine model of DSS-induced colitis. J Leukoc Biol. 2018;104(3):543–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuprys PV, Cannon AR, Shieh J, et al. Alcohol decreases intestinal ratio of lactobacillus to enterobacteriaceae and induces hepatic immune tolerance in a murine model of DSS-colitis. Gut Microbes. 2020;12(1):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takamura T, Harama D, Matsuoka S, et al. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway may ameliorate dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in mice. Immunol Cell Biol. 2010;88(6):685–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takamura T, Harama D, Fukumoto S, et al. Lactobacillus bulgaricus OLL1181 activates the aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway and inhibits colitis. Immunol Cell Biol. 2011;89(7):817–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Schwacha MG, Chaudry IH, Choudhry MA. A role of PP1/PP2A in mesenteric lymph node T cell suppression in a two-hit rodent model of alcohol intoxication and injury. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79(3):453–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rana SN, Li X, Chaudry IH, Bland KI, Choudhry MA. Inhibition of IL-18 reduces myeloperoxidase activity and prevents edema in intestine following alcohol and burn injury. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77(5):719–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrington LE, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, et al. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(11):1123–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kadaoui KA, Corthesy B. Secretory IgA mediates bacterial translocation to dendritic cells in mouse peyer’s patches with restriction to mucosal compartment. J Immunol. 2007;179(11):7751–7757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Earley Z, Akhtar S, Green S, et al. Burn injury alters the intestinal microbiome and increases gut permeability and bacterial translocation. PLoS Pathogen. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hartmann P, Chen P, Wang HJ, et al. Deficiency of intestinal mucin-2 ameliorates experimental alcoholic liver disease in mice. Hepatology. 2013;58(1):108–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanderson IR, He Y. Nucleotide uptake and metabolism by intestinal epithelial cells. J Nutr. 1994;124(1 Suppl):131S–137S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams IR, Parkos CA. Colonic neutrophils in inflammatory bowel disease: Double-edged swords of the innate immune system with protective and destructive capacity. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(6):2049–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parkos CA, Colgan SP, Madara JL. Interactions of neutrophils with epithelial cells: Lessons from the intestine. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1994;5(2):138–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedman GB, Taylor CT, Parkos CA, Colgan SP. Epithelial permeability induced by neutrophil transmigration is potentiated by hypoxia: Role of intracellular cAMP. J Cell Physiol. 1998;176(1):76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chin AC, Lee WY, Nusrat A, Vergnolle N, Parkos CA. Neutrophil-mediated activation of epithelial protease-activated receptors-1 and −2 regulates barrier function and transepithelial migration. J Immunol. 2008;181(8):5702–5710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spehlmann ME, Dann SM, Hruz P, Hanson E, McCole DF, Eckmann L. CXCR2-dependent mucosal neutrophil influx protects against colitis-associated diarrhea caused by an attaching/effacing lesion-forming bacterial pathogen. J Immunol. 2009;183(5):3332–3343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zindl CL, Lai JF, Lee YK, et al. IL-22-producing neutrophils contribute to antimicrobial defense and restitution of colonic epithelial integrity during colitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(31):12768–12773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Miranda-Perez E, Fonseca-Camarillo G, Sanchez-Munoz F, Dominguez-Lopez A, Barreto-Zuniga R. Colonic epithelial upregulation of interleukin 22 (IL-22) in patients with ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16(11):1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sugimoto K, Ogawa A, Mizoguchi E, et al. IL-22 ameliorates intestinal inflammation in a mouse model of ulcerative colitis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(2):534–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagalakshmi ML, Rascle A, Zurawski S, Menon S, de Waal Malefyt R. Interleukin-22 activates STAT3 and induces IL-10 by colon epithelial cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2004;4(5):679–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pickert G, Neufert C, Leppkes M, et al. STAT3 links IL-22 signaling in intestinal epithelial cells to mucosal wound healing. J Exp Med. 2009;206(7):1465–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolk K, Witte E, Wallace E, et al. IL-22 regulates the expression of genes responsible for antimicrobial defense, cellular differentiation, and mobility in keratinocytes: A potential role in psoriasis. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36(5):1309–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rendon JL, Li X, Akhtar S, Choudhry MA. Interleukin-22 modulates gut epithelial and immune barrier functions following acute alcohol exposure and burn injury. Shock. 2013;39(1):11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dudakov JA, Hanash AM, van den Brink MR. Interleukin-22: Immunobiology and pathology. Annu Rev Immunol. 2015;33:747–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zenewicz LA, Yancopoulos GD, Valenzuela DM, Murphy AJ, Stevens S, Flavell RA. Innate and adaptive interleukin-22 protects mice from inflammatory bowel disease. Immunity. 2008;29(6):947–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hanash AM, Dudakov JA, Hua G, et al. Interleukin-22 protects intestinal stem cells from immune-mediated tissue damage and regulates sensitivity to graft versus host disease. Immunity. 2012;37(2):339–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Munoz M, Eidenschenk C, Ota N, et al. Interleukin-22 induces interleukin-18 expression from epithelial cells during intestinal infection. Immunity. 2015;42(2):321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Munoz M, Heimesaat MM, Danker K, et al. Interleukin (IL)-23 mediates toxoplasma gondii-induced immunopathology in the gut via matrixmetalloproteinase-2 and IL-22 but independent of IL-17. J Exp Med. 2009;206(13):3047–3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Generon (Shanghai) Corporation Ltd. Study of IL-22 IgG2-fc (F-652) for subjects with grade II-IV lower GI aGVHD. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02406651. Updated 2015.

- 51.Fedorak RN, Madsen KL. Probiotics and the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10(3):286–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fedorak RN, Madsen KL. Probiotics and prebiotics in gastrointestinal disorders. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2004;20(2):146–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burke DA, Axon AT, Clayden SA, Dixon MF, Johnston D, Lacey RW. The efficacy of tobramycin in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1990;4(2):123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sutherland L, Singleton J, Sessions J, et al. Double blind, placebo controlled trial of metronidazole in crohn’s disease. Gut. 1991;32(9):1071–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steinhart AH, Feagan BG, Wong CJ, et al. Combined budesonide and antibiotic therapy for active crohn’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(1):33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Madsen K, Cornish A, Soper P, et al. Probiotic bacteria enhance murine and human intestinal epithelial barrier function. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(3):580–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schultz M, Veltkamp C, Dieleman LA, et al. Lactobacillus plantarum 299V in the treatment and prevention of spontaneous colitis in interleukin-10-deficient mice. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8(2):71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kruis W, Schutz E, Fric P, Fixa B, Judmaier G, Stolte M. Double-blind comparison of an oral escherichia coli preparation and mesalazine in maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11(5):853–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rembacken BJ, Snelling AM, Hawkey PM, Chalmers DM, Axon AT. Non-pathogenic escherichia coli versus mesalazine for the treatment of ulcerative colitis: A randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354(9179):635–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Venturi A, Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, et al. Impact on the composition of the faecal flora by a new probiotic preparation: Preliminary data on maintenance treatment of patients with ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13(8):1103–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sartor RB. Therapeutic manipulation of the enteric microflora in inflammatory bowel diseases: Antibiotics, probiotics, and prebiotics. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(6):1620–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guslandi M, Giollo P, Testoni PA. A pilot trial of saccharomyces boulardii in ulcerative colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15(6):697–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Borody TJ, Warren EF, Leis S, Surace R, Ashman O. Treatment of ulcerative colitis using fecal bacteriotherapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;37(1):42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ishikawa H, Akedo I, Umesaki Y, Tanaka R, Imaoka A, Otani T. Randomized controlled trial of the effect of bifidobacteria-fermented milk on ulcerative colitis. J Am Coll Nutr. 2003;22(1):56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takamura T, Harama D, Fukumoto S, et al. Lactobacillus bulgaricus OLL1181 activates the aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway and inhibits colitis. Immunol Cell Biol. 2011;89(7):817–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cannon A Binge alchol drinking exacerbates ulcerative colitis flare. Loyola University Chicago; 2019. [Google Scholar]