Abstract

Study Objective:

To use human-centered design approaches to engage adolescent and young adults in the creation of messages focused on dual method use in the setting of over-the-counter hormonal contraception access.

Design:

Baseline survey and self-directed workbooks with human-centered design activities were completed. The workbooks were transcribed and analyzed using qualitative methods to determine elements of the communication model-including sender, receiver, message, media, and environment.

Setting:

Indiana and Georgia

Participants:

People ages 14-21 years in Indiana and Georgia

Interventions:

Self-directed workbooks

Main Outcome Measures:

Elements of the communication model-including sender, receiver, message, media, and environment.

Results:

We analyzed 54 workbooks, with approximately half from each state. Stakeholders self-identified as female (60.5%), white (50.9%), Hispanic (10.0%), sexually active (69.8%) and heterosexual (79.2%) with a mean age of 18 years. A majority strongly agreed (75.5%) they knew how to get condoms, with only 30.2% expressing the same sentiment about hormonal contraception. Exploration of the elements of the communication model indicated the importance of crafting tailored messages to intended receivers. Alternative terminology for dual protection, such as “Condom+____,” was created.

Conclusion:

There is a need for multiple and diverse messaging strategies about dual method use in the context of over-the counter hormonal contraception to address the various pertinent audiences as this discussion transitions outside of traditional clinical encounters. Human-centered design approaches can be used for novel message development.

Keywords: Adolescent, Young Adult, Contraception, Dual Method Use, Dual Protection, Human-Centered Design, Access, Over-the-Counter

INTRODUCTION

Increased use of contraception and more effective contraceptive methods have resulted in a remarkable decline in the unintended pregnancy rate for young people in the United States.1,2 Efforts to expand access and allow for over-the-counter (OTC) hormonal contraception is being explored nationally. This type of access could help continue the trajectory of decreasing unintended pregnancy rates and increase agency and self-management for sexual health.3,4

While there has been success in unintended pregnancy outcomes for adolescents and young adults (AYA), there has been a simultaneous increase in sexually transmitted infections (STIs).5 Dual method use, or concurrent prevention of pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, can be achieved by the use of both hormonal and barrier methods of contraception at the same time. However, dual method use requires both partners’ participation, and data suggests that it is not utilized often.6-8 Previous studies have found rates ranging from 7.3%-40% with the higher rates in relationships that had a higher perceived risk of infection.9-12 Some studies report that young people using OTC hormonal contraception may forego condom use and be less likely to receive sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening and provider education.9,13,14 However, younger age, less serious relationship status, strong desire to avoid pregnancy and use of oral contraceptives (as opposed to other hormonal or longer-acting methods) have been associated with increased dual method use.9,15 While efforts have been undertaken to increase dual protection use, a 2014 Cochrane Review found few behavioral interventions that increase dual method use, and limited evidence that these interventions are effective within clinical settings.16

The movement of effective hormonal contraception outside traditional clinical settings presents new opportunities to increase both pregnancy and STI prevention. Historically, researchers have failed to include stakeholder in the development of interventions. Failing to understand stakeholder’s needs and desires prevents the success of interventions. 17-19 For AYA’s in particular, services have not always been designed with accessibility, acceptability, or appropriateness in mind.20,21

Human-centered design is a participatory research approach that is increasingly being used in healthcare to assure interventions are developed with the input of the ultimate end-user at every step of problem definition, idea generation, and prototype development. 22-25 This process assures that inclusion of insights from stakeholders is prioritized to help identify key elements of the proposed interventions. 26,27 Our study utilized human-centered design techniques to develop prototype messaging strategies for AYA’s regarding dual protection in the setting of OTC hormonal contraception, with an emphasis on dual methods.

METHODS

In conjunction with human-centered design research experts Research Jam (RJ), Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute’s Patient Engagement Core, self-directed workbooks were created for AYA stakeholders to share their insights, attitudes, and behaviors and ultimately generate a recommended communication strategy regarding dual protection in the setting of OTC access to hormonal contraception.28,29. This study was approved by the Indiana University Institutional Review Board and a waiver of parental consent was granted.

Self-Directed Workbook Creation

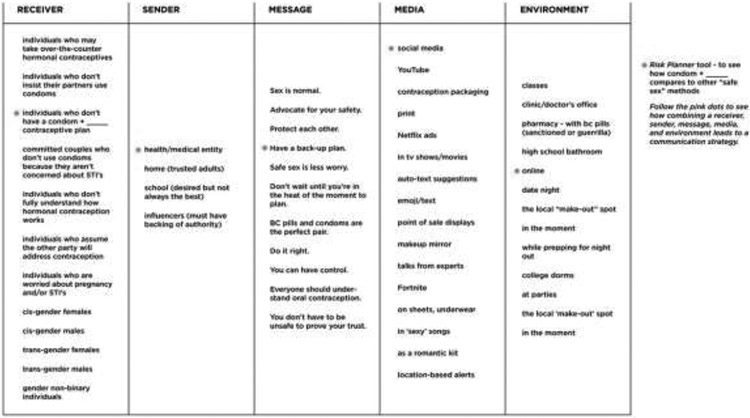

To begin, a self-directed workbook to elicit the views of AYA stakeholders regarding dual protection in the setting of OTC access to hormonal contraception was created. We designed several human-centered design activities to inform the key elements of a communication model—the sender, receiver, message, media and environment (Figure 1).30,31 Activities consisted of probes (visual or text stimuli for participants to respond to such as responding to pre-created text messages), open-ended questions (such as answering “What do you think dual protection means?”), and generative exercises (such as asking stakeholders to draw what dual protection means to them or suggest alternative names for dual protection).32,33 The workbook activities were designed to serve a wide age range of stakeholders and were intentionally gender neutral and sensitive to diversity in other respects—such as sexual orientation, race, ethnicity and previous sexual experience. (Appendix A)

Figure 1:

Elements of Communication Model

Stakeholders and Recruitment

We recruited AYA stakeholders aged 14-21 years from Georgia and Indiana through posted flyers at places frequented by young people, online advertisement on a university research study database and in-person recruitment with youth-serving organization partners (youth-advisory boards, peer educators, and school-based health centers). Stakeholders were eligible if they were 14-21 years old, lived in either state of recruitment, and could read English. We aimed for a convenience sample of 50 participants. Once 25 workbooks had been returned from a state, recruitment ended in that state. Recruitment occurred between January 2018 through December 2018.

Interested AYA stakeholders provided verbal consent and then completed a brief demographic survey. Once contact information was obtained, a workbook was either mailed or handed directly to the stakeholders for completion. A pre-addressed, pre-paid envelope was included for the workbook to be mailed back upon completion. Once a workbook was returned, a $40 gift card was sent electronically to the stakeholder. Data from the demographic surveys were de-identified and not able to be linked to returned workbook by those involved with data analysis.

Data Analysis

We performed descriptive analyses for the demographic survey to characterize the AYA stakeholders. Due to the volume of qualitative data generated, the team utilized a hybrid analysis model. The analysis and synthesis plan was based on Kolko’s process of analysis and synthesis utilizing affinity diagramming, visual modeling, and concept mapping.34 This process allowed researchers to move from raw data to themes, from themes to models, and from models to concepts. Though Kolko’s methods generally call for collaborative, synchronous analysis, the team opted to first use analysis software to identify themes then continue with hands-on analysis using pre-determined themes rather than raw data. All workbooks were transcribed and imported into NVivo software (version 12.6.0).

First, two RJ team members (KJ, CM) and the study investigators (TW, MK) independently coded five workbooks with high rates of activity completion. The four team members then met to share their codes, discuss, and refine to create a combined preliminary coding structure. Two RJ team members then used this codebook to independently code the remaining workbooks, adding and refining codes as needed. These two team members then met to discuss and make changes to the codebook, which was presented to the study investigators for approval. Once the final codes were identified, four RJ team members utilized these themes to begin visual modeling. A simplified version of the Weaver communication model (sender, receiver, message, media, and environment) was used to organize the participants’ recommendations for the ideal communication to inform dual protection messages.31 RJ then engaged in concept mapping, incorporating their visual communication design expertise to synthesize communication model elements into proposed communication strategies about dual protection in the setting of OTC hormonal contraception.

RESULTS

Sixty-seven AYA stakeholders were recruited; 53 (79%) returned the workbook for analysis (Table 1) and represented Indiana and Georgia equally. The mean age was 18 years (range 14-21). Approximately half (50.9%) self-identified as white and a majority (90.0%) were non-Hispanic. Over half (60.5%) identified as female and a majority self-identified as heterosexual (79.2%). Approximately two-thirds reported ever being sexually active, none of the stakeholders reported having been involved in a prior pregnancy, and 5.7% reported a prior STI diagnosed (Table 2).

Table 1:

Demographics of Adolescent and Young Adult Stakeholders

| State of Residence | Total (%) |

|---|---|

| Indiana | 27 (50.9) |

| Georgia | 26 (49.1) |

| Age (mean) | 18 (14-21) |

| Race | |

| White | 27 (50.9) |

| Black/African American | 19 (35.6) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 4 (7.6) |

| Multiracial | 2 (3.8) |

| Ethnicity* (n=50) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 5 (10.0) |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 45 (90.0) |

| Highest Level of Education | |

| Currently in High School | 20 (37.7) |

| High School Graduate | 17 (32.1) |

| Currently in College | 16 (30.2) |

| Self-Described Gender | |

| Male | 19 (35.9) |

| Female | 32 (60.5) |

| Prefer Not to Answer | 1 (1.9) |

| Participant Described | 1 (1.9) |

| Self-Described Sexuality | |

| Heterosexual | 42 (79.2) |

| Bisexual | 9 (17.0) |

| Participant Described | 2 (3.8) |

| Insurance | |

| Parent’s Insurance | 30 (56.6) |

| Own Insurance | 14 (26.4) |

| Out-of-Pocket | 1 (1.9) |

| Unsure | 6 (11.3) |

| Other | 2 (3.8) |

Due to missing data

Table 2:

Reproductive Health Variables of Adolescent and Young Adult Stakeholders

| Sexually Active (ever) | Total (%) |

|---|---|

| Yes | 37 (69.8) |

| No | 16 (30.2) |

| Types of Birth Control Used PreviouslyƱ (n=33) | |

| Birth Control Pill | 18 (54.5) |

| DepoProvera | 4 (12.1) |

| Arm Implant | 1 (3.0) |

| Intrauterine Device (IUD) | 7 (21.2) |

| Condoms | 28 (84.8) |

| Emergency Contraception | 8 (24.2) |

| Withdrawal | 14 (42.4) |

| Birth Control Patch/Vaginal Ring | 0 (0) |

| Frequency of Using Dual Protection | |

| All of the Time | 7 (21.2) |

| Most of the Time | 7 (21.2) |

| About half of the Time | 3 (9.1) |

| Not that Often | 6 (18.2) |

| Never | 10 (30.3) |

| “I know enough about condoms to obtain them, when needed” | |

| Strongly Agree or Agree | 53 (100) |

| “I know enough about hormonal contraception to obtain it, when needed” | |

| Strongly Agree or Agree | 34 (64.2) |

| Neutral | 11 (20.8) |

| Strongly Disagree or Disagree | 8 (15.1) |

| Previous Pregnancy | 0 |

| Previous Sexually Transmitted Infection | 3 (5.7) |

Stakeholders allowed to select more than one method

A majority reported previous experience with condoms; the next most common form of contraception ever used was birth control pills. Of those reporting sexual activity, 42.4% reported using dual protection either all or most of the time. All AYA stakeholders strongly agreed/agreed they could obtain condoms when needed, but fewer AYA stakeholders (64.2%) said the same about hormonal contraception (Table 2).

Communication Model Elements

We explored the five elements of the communication model (sender, receiver, message, media, and environment) through qualitative analysis of the returned workbooks.

Sender

AYA stakeholders discussed their current sources of education and information regarding sexual health. AYA stakeholders expressed a desire to receive sexual health education from school.

I wish I learned more about birth control and safe sex from high school. Everything I learned was from the internet.

[It would make it easier] if my high school talked about safe sex and birth control instead of abstinence.

Information from peers, non-reputable or biased sources was deemed less trustworthy. Although many AYA stakeholders indicated that learning about safe sex practices online would be ideal, they were skeptical that reliable websites exist. Stakeholders identified several reputable sources including doctors, pharmacists, known reproductive health organizations, and adult family members.

[The worst place to get advice about sex is my] peers who are uninformed….my frat friends….boys my age… a religious sex ed class… unreliable sources for information, such as Wikipedia.

Receiver

AYA stakeholders generally demonstrated a strong understanding of safe sex practices and could describe the benefits of condom and contraceptive use. Regarding the use of condoms and contraception, stakeholders endorsed the need for planning and self-advocacy. They also described a sense of individual responsibility for each partner that were often gender-specific.

You should always have condoms and she should have birth control.

I would think since I am a guy, I don’t have to worry about them (pills). My job is to focus on condoms.

I wouldn’t look for more info [about birth control] because I am not a female.

AYA stakeholders frequently mentioned trust and relationship type as influences of dual protection use, and condoms, in particular.

I’ve heard horror stories of “trustworthy” people that people have known for years, only to have that [trust] taken advantage of. I love you, but I wouldn’t trust anyone with my future.

I personally would still want to use [condoms] if I don’t trust a new partner, but it might deter people from having to buy both.

While there was a sentiment of interest in OTC hormonal contraception due to the decreased barriers of access, concerns and conflicting opinions were expressed.

I would feel slightly uncomfortable because anyone could buy it, so more young people would have sex. On the other hand, it would encourage young people to have safe sex.

I would be worried about the quality of the birth control. Is it a good brand?

Many AYA stakeholders felt that having hormonal contraception available over the counter would encourage safe sex practices and promote methods to reduce STIs and unintended pregnancy.

[I’m excited about having] more independence and the right to make my own decisions and being safe with those decisions.

…it would make me think of birth control as an equally convenient/readily available method of protection as condoms.

Message

AYA stakeholders thought emphasis on protecting against all negative outcomes as well as redundancy of protection were important.

[Protection means] not having to worry about getting pregnant and contracting an STD or HIV AIDS.

[One reason to use both birth control pills and a condom is] as a backup in case one of them fails.

However, they did not find the phrase “dual protection” meaningful.

The only problem I see with it is that the name doesn’t fully describe the concept it names.

Maybe a name that includes the fact that it pertains to sex or that clarifies that it describes condom + hormonal.

AYA stakeholders noted that messages should avoid trying too hard to appeal to a younger audience in an attempt to appear “cool”. Lastly, stakeholders shared that safe sex messages for adolescents are often heteronormative and fail to include diverse gender identities and sexual orientations.

I’m not sure. It might be concerning that the term assumes that a couple is heterosexual- man + woman where one uses one thing, one uses the other.

It implies that gay people are naturally going to have only one “layer” of protection, doesn’t it? Heteronormative and possibly exclusionary, discomforting…

I think that “dual protection” is an alright name, but be careful how you advertise it! Don’t assume your whole audience is in a heterosexual relationship!

Environment

Potential places where stakeholders might encounter messaging included environments that AYA stakeholders frequent as well as environments that could be involved in obtaining OTC hormonal contraception. For example, a pharmacy is a common touch point for obtaining contraception, either over the counter or with a prescription, and could serve as one environment to target messaging.

Although many AYA stakeholders indicated that learning about safe sex practices online would be ideal, they were skeptical that reliable websites exist with this information and emphasized that official websites with “.org” addresses could be trusted more. When asked directly where the best place is to get advice about sex, answers often included “a doctor’s office,” while worst places included a “locker room,” or a “public high school.”

Media

In terms of the way to communicate these messages, AYA stakeholders highlighted media frequently used by young people (i.e.; social media and trusted websites) as important. They also suggested that location-based alerts (i.e.; at a pharmacy where both condoms and hormonal contraception can be accessed) and package messaging could be helpful.

It would be ideal if over-the-counter contraception included something like “does not protect against sexually transmitted infections”

Synthesis of Communication Elements

We synthesized the communication model elements to create prototype messaging strategies for dual protection in the setting of OTC hormonal contraception (Figure 2). A messaging strategy can consist of a combination of choices from the receiver, sender, message, media, and environment elements. Just as there is not a singular sender or receiver, there are similarly multiple spaces, places, and media that can be used as part of dual protection messaging for young people in the setting of OTC hormonal contraception. The synthesis table shows examples of how various combinations can be made to create prototype messages. The pink dot is an example of how you can combine a particular receiver, sender, message, media and environment elements to create a communication strategy. There is not just one receiver or audience of these messages, therefore different messages for diverse genders, relationships and experiences are needed. Messages focusing on advocating for oneself, having a back-up plan, and normalization of sexuality, as opposed to the message of risk and fear, resonated with our AYA stakeholders.

Figure 2:

Synthesis of Communication Model Elements and Prototype Messaging Elements

The term “dual protection” was not meaningful to our AYA stakeholders. As an alternative term for dual protection, the phrase “Condom + _____” was created to indicate that barrier protection (male or female condoms) should always be included in a safe sex plan. It avoids the potential confusion of users selecting two hormonal methods in an attempt to achieve dual protection. It visually indicates that something is missing, giving space for end-users to “fill in the blank” with the form of contraception or other prevention methods that would be added. Furthermore, this implies individualization based on the dynamics of the receiver’s relationship, gender identity and preferences and not a proscriptive answer that works for everyone. Its visual similarity to a math problem allows for flexibility in messaging to reflect the communication needs of the situation and the sender (i.e. “Condom + ____ = a healthy future, no worries”, etc.).

CONCLUSIONS

Our study utilized human-centered design techniques to inform communication strategies for AYA’s about dual protection in the setting of OTC access to hormonal contraception. Human-centered design is not new, but its application in healthcare has been more recent.22-25 The importance of stakeholder engagement in research and interventions is critical and necessary for success.35-39 Our findings suggest that AYA’s are enthusiastic about the concepts underlying dual protection and would like to hear and see more about its benefits from reliable sources. Knowing that AYA’s disproportionately experience unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection, it is important to explore ways that messaging on dual protection can be communicated even in advance of hormonal contraception being available over the counter.

Our study showed that no single message will be sufficient as there are multiple receivers that will benefit from messaging about dual protection in multiple contexts. As hormonal contraception becomes increasingly available over the counter, the number and types of people that will have to access it, and the environments in which they access it, will broaden. Therefore, messages about dual protection will need to shift accordingly to new settings and to broader audiences. Successful dual protection messaging in this new paradigm will need to consider multiple messages, media, environments (at point-of-sale, via social media), and receivers, including adults and evolve over time to feedback.

Some additional notable opportunities for messaging became clear in our study. For example, young men can be further engaged in supporting and understanding their partner’s use of hormonal contraception. Previous literature has examined the gendered roles of responsibility based on the type of contraception.40 Additional literature has shown that incorporating male-focused health services is necessary to provide family planning for the larger population.41 Our findings support this and suggest that rather than presenting a “girls vs. boys” or “that’s his/her job” in messaging, we should reinforce collaboration and synergy between the partners. Messaging can underscore that there is maturity in having sexual health conversations and can model how to initiate them by providing language that resonates with young people.

While the receiver of dual protection messages in this study was considered to be the AYA accessing OTC hormonal contraception, there is also an opportunity for messages focused on parents and other trusted adults, as respondents noted that they are perceived as reliable sources of information for young people. A recent meta-analysis found that parent-based interventions for adolescent sexual health were associated with improved condom use and parent-child communication regarding sexual health.42 This supports creation and refinement of messages geared towards parents as message-receivers in ways that facilitate them as message-senders.

There are some limitations to this study. First, we only engaged a small sample of AYA stakeholders from two states in this research. While their insights were informative, they should not be taken to reflect all young people’s opinions. Second, AYA stakeholders primarily self-identified as heterosexual. While we focused on making our study tools neutral and applicable to a diverse set of stakeholders, future work should specifically seek the input of underserved populations, including (but not limited to) sexual and gender minorities. Finally, while human-centered design is an important element when creating a messaging strategy, these messages have not yet been associated with protective behaviors, which is ultimately the goal of these efforts.

Nonetheless, we believe this adds to the literature and supports the theory that human-centered design is important in health research to assure that the end-user is integral to the development of interventions. Messaging strategies around dual protection in the setting of over-the-counter contraception will benefit from the utilization of the communication model components discussed. This will help messages resonate with AYAs, and encourage behaviors noted in the messaging to be adopted. Anticipated next steps would be to test these prototype messages and expand to include messages to even broader audiences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank all the adolescents and young adults who participated in this study and the OC OTC Working Group for their support of this work. We also would like to thank the additional members of Research Jam, Brandon Cockrum, Dustin Lynch, Lisa Parks and Gina Claxton, for their individual contributions to this work.

We thank all the young people that participated in this study and provided their insight and time.

Funding:

This work was supported by a grant from Ibis Reproductive Health, the NICHD K23 Award (HD099274-01) and with support from the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute which is funded in part by Award Number UL1TR002529 from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Sciences Award. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations:

- AYA

adolescents and young adults

- OTC

over-the-counter

- STI

sexually transmitted infection

- RJ

Research Jam

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Wilkinson receives project funding from Bayer, Cooper Surgical and Organon. None of the other authors have conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):843–852. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1506575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindberg LD, Santelli JS, Desai S. Changing Patterns of Contraceptive Use and the Decline in Rates of Pregnancy and Birth Among U.S. Adolescents, 2007–2014. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(2):253–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grossman D, Grindlay K, Li R, Potter JE, Trussell J, Blanchard K. Interest in over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives among women in the United States. Contraception. Oct 2013;88(4):544–52. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sindhu KK, Adashi EY. Over-the-Counter Oral Contraceptives to Reduce Unintended Pregnancies. JAMA. 2020;324(10):939–940. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.21862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2020. 2020. Accessed June 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2020/tables.htm

- 6.El Ayadi AM, Rocca CH, Kohn JE, et al. The impact of an IUD and implant intervention on dual method use among young women: Results from a cluster randomized trial. Prev Med. Jan 2017;94:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higgins JA, Smith NK, Sanders SA, et al. Dual method use at last sexual encounter: a nationally representative, episode-level analysis of US men and women. Contraception. Oct 2014;90(4):399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pazol K, Kramer MR, Hogue CJ. Condoms for dual protection: patterns of use with highly effective contraceptive methods. Public Health Rep. Mar-Apr 2010;125(2):208–17. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenberg DL, Allsworth JE, Zhao Q, Peipert JF. Correlates of dual-method contraceptive use: an analysis of the National Survey Of Family Growth (2006-2008). Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:717163. doi: 10.1155/2012/717163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown JL, Hennessy M, Sales JM, et al. Multiple method contraception use among African American adolescents in four US cities. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2011;2011:765917. doi: 10.1155/2011/765917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.STDs in Adolescent and Young Adults. 2017. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017. Accessed 6/2/2019. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/adolescents.htm#ref1

- 12.Kottke M, Whiteman MK, Kraft JM, et al. Use of Dual Methods for Protection from Unintended Pregnancy and Sexually Transmitted Diseases in Adolescent African American Women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015;28(6):543–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2015.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ott MA, Adler NE, Millstein SG, Tschann JM, Ellen JM. The trade-off between hormonal contraceptives and condoms among adolescents. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. Jan-Feb 2002;34(1):6–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manski R, Kottke M. A Survey of Teenagers' Attitudes Toward Moving Oral Contraceptives Over the Counter. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. Sep 2015;47(3):123–9. doi: 10.1363/47e3215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kottke M, Whiteman MK, Kraft JM, et al. Use of Dual Methods for Protection from Unintended Pregnancy and Sexually Transmitted Diseases in Adolescent African American Women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. Dec 2015;28(6):543–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2015.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopez LM, Stockton LL, Chen M, Steiner MJ, Gallo MF. Behavioral interventions for improving dual-method contraceptive use. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Mar 30 2014;(3):Cd010915. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010915.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forsythe LP, Ellis LE, Edmundson L, et al. Patient and Stakeholder Engagement in the PCORI Pilot Projects: Description and Lessons Learned. J Gen Intern Med. July/10 01/23/received 04/28/revised 06/05/accepted 2016;31(1):13–21. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3450-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frampton S, Guastello Sara, Hoy Libby, Naylor Mary, Sheridan Sue, Johnston-Fleece Michelle. Harnessing Evidence and Experience to Change Culture: A Guiding Framework for Patient and Family Engaged Care: A Discussion Paper. 2017; https://nam.edu/harnessing-evidence-and-experience-to-change-culture-a-guiding-framework-for-patient-and-family-engaged-care/

- 19.Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. Feb 26 2014;14:89. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adolescent Health Services: Missing Opportunities. National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raymond EG, Stewart F, Weaver M, Monteith C, Van Der Pol B. Impact of increased access to emergency contraceptive pills: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. Nov 2006;108(5):1098–106. doi:108/5/1098[pii] 10.1097/01.AOG.0000235708.91572.db [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.IDBM Program. vol Volume 1. IDBP Papers. Aalto University; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Searl MM, Borgi L, Chemali Z. It is time to talk about people: a human-centered healthcare system. Health Res Policy Syst. 2010;8:35. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-8-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones JHC, Thornley DG. Conference on Design Methods. Pergamon Press; 1963:xiii, 222 p. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matheson GO, Pacione C, Shultz RK, Klugl M. Leveraging human-centered design in chronic disease prevention. Am J Prev Med. Apr 2015;48(4):472–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bindman AB. The evolution of health services research. Health Serv Res. Apr 2013;48(2 Pt 1):349–53. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Research ICfPH. Position Paper 1: What is Participatory Health Research? Version: Mai 2013. International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanders EBN. Postdesign and Participatory Culture. presented at: Proceedings of Useful and Critical: The Position of Research in Design; 1999; Helsinki: University of Art and Design. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanders E WC. Harnessing people’s creativity: Ideation and expression through visual communication. In: Langford J, McDonagh Deana, ed. Focus Groups: Supporting Effective Product Development. Taylor & Francis Group; 2003:chap Chapter 10. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiske J. Introduction to communication studies. 2nd ed. Studies in culture and communication. Routledge; 1990:xvi, 203 p. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shannon CE. A mathematical theory of communication. The Bell System Technical Journal. 1948;27(3):379–423. doi: 10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanders EBN, Stappers PJ. Probes, toolkits and prototypes: three approaches to making in codesigning. CoDesign. 2014/January/02 2014;10(1):5–14. doi: 10.1080/15710882.2014.888183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanders EB-N, Stappers PJ. Convivial Toolbox: Generative Research for the Front End of Design. 2013: [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kolko J. Exposing the magic of design : a practitioner's guide to the methods and theory of synthesis. Oxford series in human-technology interaction. Oxford University Press; 2011:xvii, 185. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar A, Maskara S, Chiang IJ. Building a prototype using Human-Centered design to engage older adults in healthcare decision-making. Work (Reading, Mass). 2014;49(4):653–61. doi: 10.3233/wor-131695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Couture B, Lilley E, Chang F, et al. Applying User-Centered Design Methods to the Development of an mHealth Application for Use in the Hospital Setting by Patients and Care Partners. Appl Clin Inform. Apr 2018;9(2):302–312. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1645888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harte R, Glynn L, Rodríguez-Molinero A, et al. A Human-Centered Design Methodology to Enhance the Usability, Human Factors, and User Experience of Connected Health Systems: A Three-Phase Methodology. JMIR Hum Factors. 2017;4(1):e8–e8. doi: 10.2196/humanfactors.5443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eberhart A, Slogeris B, Sadreameli SC, Jassal MS. Using a human-centered design approach for collaborative decision-making in pediatric asthma care. Public Health. May 2019;170:129–132. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Witteman HO, Dansokho SC, Colquhoun H, et al. User-centered design and the development of patient decision aids: protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):11–11. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilliam M, Woodhams E, Sipsma H, Hill B. Perceived Dual Method Responsibilities by Relationship Type Among African-American Male Adolescents. J Adolesc Health. Mar 2017;60(3):340–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Besera G, Moskosky S, Pazol K, et al. Male Attendance at Title X Family Planning Clinics - United States, 2003-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Jun 17 2016;65(23):602–5. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6523a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Widman L, Evans R, Javidi H, Choukas-Bradley S. Assessment of Parent-Based Interventions for Adolescent Sexual Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysisAssessment of Parent-Based Interventions for Adolescent Sexual HealthAssessment of Parent-Based Interventions for Adolescent Sexual Health. JAMA Pediatrics. 2019;doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.2324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.