Abstract

The Ediacaran biota were soft-bodied organisms, many with enigmatic phylogenetic placement and ecology, living in marine environments between 574 and 539 million years ago. Some studies hypothesize a metazoan affinity and aerobic metabolism for these taxa, whereas others propose a fundamentally separate taxonomic grouping and a reliance on chemoautotrophy. To distinguish between these hypotheses and test the redox-sensitivity of Ediacaran organisms, here we present a high-resolution local and global redox dataset from carbonates that contain in situ Ediacaran fossils from Siberia. Cerium anomalies are consistently >1, indicating that local environments, where a diverse Ediacaran assemblage is preserved in situ as nodules and carbonaceous compressions, were pervasively anoxic. Additionally, δ238U values match other terminal Ediacaran sections, indicating widespread marine euxinia. These data suggest that some Ediacaran biotas were tolerant of at least intermittent anoxia, and thus had the capacity for a facultatively anaerobic lifestyle. Alternatively, these soft-bodied Ediacara organisms may have colonized the seafloor during brief oxygenation events not recorded by redox proxy data. Broad temporal correlations between carbon, sulfur, and uranium isotopes further highlight the dynamic redox landscape of Ediacaran-Cambrian evolutionary events.

Subject terms: Element cycles, Marine chemistry

Geochemical data from sedimentary rocks in Siberia indicate that members of the soft-bodied Ediacara biota (the earliest macroscopic life on Earth) were tolerant of low-oxygen conditions, suggesting they had the capacity for anaerobic metabolisms.

Introduction

Of the enigmatic Ediacaran biotas—the earliest macroscopic organisms on Earth that persisted for about 35 million years (ca. 574-539 Ma) in globally distributed marine environments—the Rangeomorphs, characterized by their modular organic-walled fronds and fractal level of organization, are considered by some to represent stem group eumetazoans1. However, because of their unusual moldic preservation in sandstones (or as nodules or carbonaceous compressions in carbonates) and bizarre quilted morphologies, the metabolic requirements of these organisms remain controversial. Given the extreme surface area of the fronds, which preserve similar patterns at increasingly smaller scales2,3, recent interpretations of Rangeomorph feeding strategies range from osmotrophy (absorption of labile dissolved organic carbon from seawater), to chemosymbiosis (with autotrophic sulfur-oxidizing bacteria), to extracellular digestion within semi-isolated chambers (including a resident microbiome)4–10. Other hypotheses suggest an aerobic metabolism for the Rangeomorphs11,12, leading to the hypothesis that a rise in the oxidation state of seawater along continental shelves was the primary controlling factor in their evolution, and its fall to their extinction13. To the contrary, if the Rangeomorphs did not require oxygen for their metabolism, their evolution may have been independent of ocean redox conditions.

Distinguishing between these two hypotheses is critical to understanding the biological affinity of the Ediacaran biotas, and requires constraints on the redox conditions under which they lived. Emerging evidence suggests a highly dynamic oxidation state through Ediacaran space and time. Based on geochemical evidence, the geological period may be divided into discrete intervals with different proportions of oxic13–16 and anoxic seafloor conditions17,18. Furthermore, data support the presence of redox gradients across facies on individual platforms, suggesting that the regional distribution of Ediacaran organisms was dependent on the oxidation state of overlying seawater19–23. Globally, most of the fossils of soft-bodied organisms are preserved as casts and molds in medium- to coarse-grained sandstones—which are not amenable to paleo-redox reconstruction—rather than in fine-grained shales, which do contain distributions of redox-sensitive elements that may be used to reconstruct environmental conditions24. In rare and fortuitous instances, Ediacaran biotas have been preserved as nodules and compressions in carbonates, for which proxies for both local and global redox conditions have been calibrated. Here, we present high-resolution time-series data for both local and global ocean redox in carbonates from arctic Siberia that also contain Rangeomorphs, along with a numerically-abundant assemblage of macrofossils consisting of Arboreomorphs (frondose organisms with holdfasts rooted in substrate), undifferentiated bulbous structures with tubules reaching into surrounding sediments, and large carbonaceous compressions.

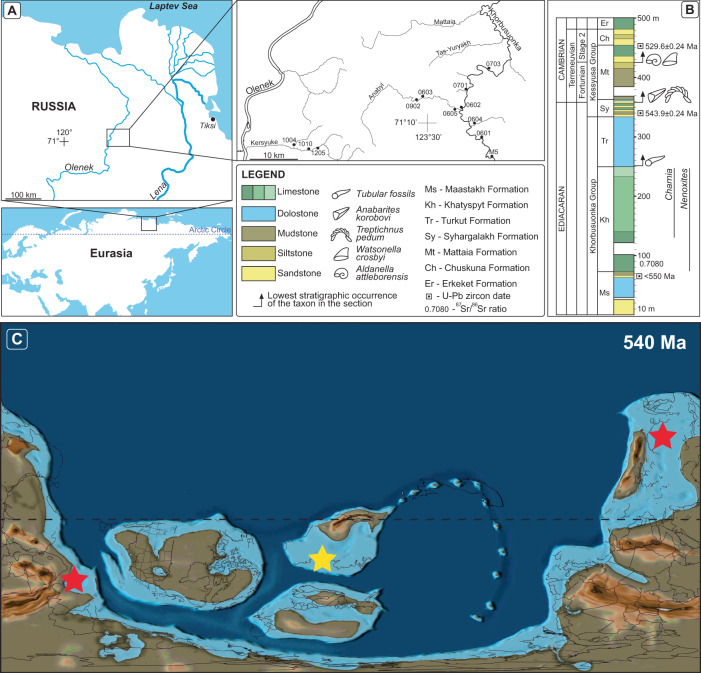

The Olenek Uplift region of northeastern Siberia contains a well-studied succession of terminal Ediacaran to lower Cambrian strata, including five units of primary interest: (1) the Maastakh Formation, consisting of partially silicified peritidal dolostone with chert nodules, cross-bedding, and wave ripples; (2) the fossiliferous Khatyspyt Formation, consisting of thin- to medium-bedded bituminous limestone; (3) the Turkut Formation, comprising dolostone and limestone with several levels of collapse breccia filled with pyrobitumen that may be related to evaporite dissolution; (4) siliciclastics and volcanics of the Syhargalakh Formation; and (5) mixed siliciclastics and allodapic limestones of the Mattaia Formation25–28 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Geologic and paleogeographic background of the Olenek Uplift.

A Map of the study area and measured sections along the Khorbusuonka and Olenek River areas of northeastern Siberia. B Generalized stratigraphic column of the study units including lithology, fossil content, and radiometric age constraints. 87Sr/86Sr value from ref. 8 and radiometric ages from refs. 30, 33, and this study. Maps in panels A and B were created by the authors using: www.yandex.ru/maps. C Paleogeographic map from 540 Ma with the Olenek Uplift section examined in this study denoted by the yellow star and the coeval Namibia and South China sections denoted by the red stars. Base map from, ref. 102: Scotese, C.R., 2021. An Atlas of Paleographic Maps: The Seas Come In and the Seas Go Out, Annual Reviews of Earth and Planetary Sciences, v. 49, p. 669–718.

Detrital zircon U-Pb isotopic ages provide a maximum depositional age of 550 Ma for a sandstone near the top of the Maastakh Formation (see Supplementary Discussion; Supplementary Figs. 11, 12). This age is relevant because it constrains the overlying Khatyspyt Formation as younger than 550 Ma, which resolves an important uncertainty in late Ediacaran chronostratigraphy29. Specifically, 87Sr/86Sr values for the Khatyspyt Formation are lower (near 0.7080; ref. 8) than other late Ediacaran successions from China, Oman, and Australia deposited during and after the Shuram excursion, which left an uncertainty as to whether the Khatyspyt Formation was older or younger that those successions. Our U-Pb age resolves this issue and places the Khatyspyt Formation in the terminal Ediacaran Period, younger than 550 Ma. A terminal Ediacaran age is supported for the Turkut Formation and underlying units by a U-Pb zircon date of 543.9 ± 0.24 Ma generated for a tuff breccia within the Syhargalakh Formation30. While this date was originally thought to provide a constraint on the Ediacaran-Cambrian boundary, a U-Pb zircon age of ca. 538.8 Ma from Namibia provides a new radiometric marker for this critical transition31, and refs. 29, 32. further suggested that the Ediacaran-Cambrian boundary may be <538 Ma based on the presence of Ediacara-type fossils up to an ash bed dated to 538.3 ± 0.14 Ma in South Africa and the inference that the base of the Cambrian Period (defined bio- and chemostratigraphically) must be younger than this horizon. A second U-Pb zircon date of 529.56 ± 0.24 Ma in a volcanic ash immediately overlying the Mattaia carbonate platform33 constrains the age of small shelly fossils (SSFs) of the N. sunnaginacus Zone and thereby the onset of the Cambrian explosion28.

The Olenek Uplift is known for containing well-preserved nodules and carbonaceous compressions of Ediacaran organisms, including the first preserved appearance of Nenoxites curvus and a diverse Ediacara assemblage of soft-bodied organisms in the Khatyspyt Formation (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2), which are morphologically and environmentally similar to Avalon-type fossils from Newfoundland34. The Turkut Formation contains the first appearance of tubular steinkerns, which are preserved as smooth-walled molds. While the first SSFs of Cambrian aspect (Anabarites trisulcatus assemblage Zone) appear near the base of the Syhargalakh Formation, the lowest occurrence of Treptichnius pedum (the ichnospecies associated with the Ediacaran-Cambrian boundary) and Rusophycus (a likely arthropod resting trace) are found at the top of the Syhargalakh Formation. Stratigraphically higher in the Mattaia Formation, more complex traces of organisms that burrowed deeply into the sediments, as well as transported SSFs of the lower Cambrian Fortunian Stage Purella antiqua and Cambrian Stage 2 Nochoroicyathus sunnaginicus assemblage zones, are found in siliciclastic and carbonate facies28.

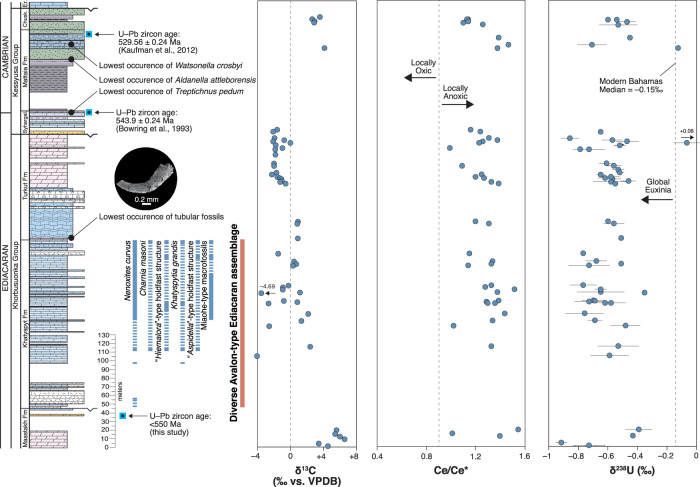

Carbon isotopes (δ13C) are used to correlate Olenek Uplift strata with other terminal Ediacaran and basal Cambrian successions worldwide, in particular to coeval intervals in South China (see ref. 29 for review). In arctic Siberia, time-series δ13C values show a decreasing trend from near +6‰ in the Maastakh and basal Khatyspyt formations, and then an oscillation between −5 and +4‰ through the overlying reaches of the interval25,26,35 before stabilizing near 0‰ in dolostones of the lower Turkut Formation. In the upper levels of the Turkut Formation, δ13C values are noted to stratigraphically decline to as low as −4‰ before the carbonate platform is regionally truncated beneath a disconformity surface. Carbonates in the overlying Mattaia Formation preserve a negative-to-positive trend, ending in peak values as high as +5‰ (Fig. 2) associated with SSFs of the N. sunnaginicus assemblage Zone marking the base of Cambrian Stage 228. Correlation to South China suggests that the strongly positive δ13C values in the Maastakh Formation are equivalent to similarly high values in the basal Dengying Formation (Beiwan Member36), while a second positive carbon isotope peak in the Gaojiashan Member associated with the first appearance of Cloudina in South China35 most likely equates to a similar magnitude excursion in the Khatyspyt Formation. The negative δ13C excursion seen across the Ediacaran-Cambrian boundary (BACE event37) beginning at the top of the Dengying Formation in South China (where values drop to as low as −7‰) may begin in the upper Turkut Formation25,26, but the sedimentary rocks preserving the negative carbon isotope anomaly are regionally truncated at an unconformity surface below siliciclastics of the Syhargalakh Formation. Alternatively, the shift towards negative δ13C values in the upper Turkut Formation could correlate with the A4 anomaly, which is a negative δ13C excursion identified as older than the BACE event in Oman29,32. Higher in the succession, peak δ13C values of the Mattaia carbonate platform are potentially equivalent to those in the Zhujiaqiang Formation of South China, which are also biostratigraphically constrained to Cambrian Stage 2 based on the first appearance of N. sunnaginacus assemblage Zone fossils.

Fig. 2. Olenek Uplift chemostratigraphy.

Stratigraphic column, fossil occurrences, and geochemical data (δ13C, δ238U, and Ce/Ce*) for our composite Olenek Uplift section. δ13C data are from ref. 99. Paleontology is described in detail in ref. 34. Modern Bahamas median δ238U value is from ref. 55 and oxic/anoxic Ce/Ce* cutoff value of 0.9 is from ref. 21. Note that the U-Pb zircon age of 543.9 ± 0.24 Ma published by ref. 30 from the Syhargalakh Formation was reinterpreted as 542.8 ± 1.3 Ma using the most concordant grains by ref. 103.

The time-series trend in sulfur isotope (δ34S) compositions of pyrite in acidified residues from Khatyspyt limestones may further provide a chemostratigraphic marker of terminal Ediacaran time. The stratigraphic data show a profound shift from −20 to +30‰ that has been interpreted as a change in redox conditions and/or sulfate availability on a regional or global scale20. Notably, the first appearance of soft-bodied Ediacara biotas in the Khatyspyt Formation and a positive δ13C excursion are associated with this prominent perturbation in seawater chemistry. A remarkably similar sulfur isotope anomaly is recorded in the Gaojiashan Member of the Dengying Formation, which is associated with the upper of the two positive carbon isotope excursions in the formation, and the first evidence for metazoan biomineralization in South China35. Examples of Ediacaran ‘superheavy pyrite’ in the aftermath of the Shuram Excursion are also known from Oman38, Namibia39, northwestern Canada40, and northwestern China41. Some Ediacaran ‘superheavy pyrite’ values have been attributed to anomalies in laboratory extraction methods42 or thermochemical sulfate reduction within hydrothermal fluids43. However, their coincidence specifically in post-Shuram successions worldwide supports the view that these events can be used as chemostratigraphic markers, and most-likely reflect significant changes in the redox landscape of the global ocean.

Here we investigate local redox conditions in both limestones and dolostones of the Olenek Uplift succession using the magnitude of cerium (Ce) anomalies. Cerium is a redox-sensitive rare earth element (REE) where Ce(III) can be partially oxidized to Ce(IV) under oxic conditions. This causes a decrease in solubility, which results in Ce removal from seawater. Modern well-oxygenated seawater is thus depleted in Ce relative to other trivalent rare-earth elements (REEs), resulting in a pronounced negative Ce anomaly (Ce/Ce* = [Ce]/([Pr]2/[Nd]) < 1 with element concentrations normalized to the post-Archean Australian shale)44. In contrast, Ce stays in solution under anoxic conditions and anoxic waters have little to no Ce anomaly, as evidenced by Ce/Ce* values that are close to or >1 below the chemocline in many modern anoxic basins45. Cerium oxidation is closely linked to the redox kinetics of manganese (Mn) such that the presence/absence of a Ce anomaly is specifically sensitive to the position of a sample with respect to the Mn redoxcline45. In the suboxic portion of the modern Black Sea, Mn is actively oxidized at O2 concentrations below analytical detection (<3 μM)46, which helps constrain the threshold needed to generate a negative Ce anomaly. Marine carbonates can preserve a reliable record of seawater REE patterns—as a substitution for Ca2+ in carbonate minerals47—if diagenetic alteration and detrital contamination are minimized48, with a recent study of modern Bahamian carbonates indicating that REE signals are particularly resistant to diagenesis49. Samples can be screened for detrital influence using yttrium to holmium (Y/Ho) ratios, with values >36 indicating an authigenic seawater signal48.

We also estimate global seawater redox conditions, in large part related to the extent of euxinic (free H2S in the water column) conditions, using uranium (U) isotopes. Uranium in nature is dominated by two long-lived isotopes, 235U and 238U, whose half-lives are 0.7 and 4.5 Ga, respectively. In nature, U exists in predominantly two oxidation states: soluble U(VI) and insoluble, particle-reactive U(IV). Soluble U(VI) forms unreactive, stable calcium-uranyl-bicarbonate complexes in seawater. It is well-mixed and isotopically homogenous in the modern ocean with an isotopic composition of −0.39‰50. Among various sinks for U in the ocean, the strongest isotopic fractionation is associated with removal of U to euxinic sediments, which preferentially sequester isotopically-heavy 238U, thereby leaving residual seawater more enriched in isotopically light 235U. Thus, an expansion of ocean euxinia will drive the δ238U composition of global seawater towards lower values. Recent data suggest that substantially less fractionation occurs under ferruginous (free Fe2+ in the water column) conditions51 and suboxic conditions52 than under euxinic conditions. Thus, U isotopes are increasingly considered a proxy specifically for marine euxinia52,53. Reference 54 also found a relationship between the degree of isotopic fractionation imparted during U removal to anoxic sediments and hydrographic factors such as primary productivity and basin restriction. Despite these complications, the size of the euxinic sink for U in the oceans clearly exerts a primary control on seawater δ238U values. The δ238U signal of seawater can faithfully be recorded in marine carbonate sediments under certain conditions, with modern Bahamian carbonates showing a small but consistent isotopic offset between seawater and sediment regardless of burial depth and mineralogy (Bahamas median = −0.15‰ vs. seawater = −0.39‰)55. Taken together, a shift towards lighter U isotopes in ancient carbonates can be interpreted as an expansion of global marine euxinia.

Ultimately, this study combines proxies for local (Ce anomaly) and global (U isotope) redox conditions in the same carbonate strata that preserve in situ Ediacaran fossils, thus allowing us to examine the redox context of the enigmatic biota. The occurrence of well-preserved Ediacaran fossils in carbonate environments allows us to directly link in situ oxidation state, global ocean redox, and fossil assemblages in the same strata, thus providing important constraints on the redox-dependence and metabolism of early macroscopic life on Earth.

Results

Diagenesis

We initially assessed the diagenetic grade of our 56 selected Olenek Uplift carbonates using petrographic observations and typical geochemical tracers such as the manganese to strontium (Mn/Sr) ratios and oxygen isotope (δ18O) compositions. Petrographic analysis (Supplementary Figs. 3–6) of most samples revealed a fine-grained micritic to microsparitic matrix with the presence of fine, organic-rich laminations in the Khatyspyt Formation, as well as micritic carbonates associated with transported skeletal fossils in the Mattaia Formation. In contrast, the Turkut Formation contains fine-grained dolomicrite and dolomicrosparite in most intervals, with occasional horizons of coarse interlocking dolomite spar that indicate fabric-destructive recrystallization. The Mn/Sr ratio (less than the typical cutoff value of 10; ref. 56) also indicates a high degree of preservation for the sample set, with the exception of the coarser dolomites from the upper Turkut Formation. The range of δ18O values (between −0.65 and −8.38‰) are in a reasonable range for well-preserved Proterozoic carbonates57 with the heaviest values in the Turkut Formation consistent with the presence of collapse breccias potentially associated with evaporative conditions. We find no relationship between carbon and oxygen isotope abundances in our sample set that would suggest diagenetic alteration (Supplementary Fig. 7)58, and no covariation between diagenetic indicators (Mn/Sr or δ18O) and U isotope (Supplementary Fig. 7) or Ce anomaly (Supplementary Fig. 8) values, indicating that these parameters have not been systematically altered through diagenetic processes.

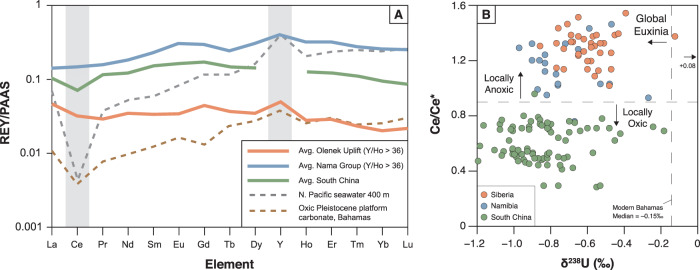

Cerium anomaly

REE distributions in carbonates are currently recognized as a powerful tool to evaluate seawater patterns and redox conditions in ancient depositional basins. Given their low abundance, however, careful leaching of samples is required to avoid contamination from siliciclastic components. To this end, we used a step-wise extraction technique using dilute acids, and measured Y/Ho in our leachates21,49 to evaluate the fidelity of the samples. The majority of our samples show Y/Ho elevated above the detrital background (>36), resulting in a positive Y anomaly and a strongly hydrogenous (seawater) REE signal (Fig. 3). Considering only samples with Y/Ho >36, Ce/Ce* values range from 0.99 to 1.55, with a median value of 1.30, and no evidence for systematic stratigraphic changes across formation boundaries (Fig. 2). No negative Ce anomalies are recorded in any of the samples from our section. This is strong evidence for deposition beneath a largely anoxic water column through the entire Olenek Uplift succession. Reference 21 suggested that positive Ce anomalies (as are recorded in many of our samples) could be indicative of manganous conditions in the water column wherein Ce is added back to sediments by sorption to Mn (oxy)hydroxides. In that study, manganous conditions were accompanied by enrichment in Mn/Fe ratios (>0.29), which are much higher than found in the current Olenek sample set (median = 0.09). This suggests that local seawater conditions in the Olenek basin were more likely ferruginous. When considering each formation separately, the Maastakh, Khatyspyt, and Turkut formations all have low median Mn/Fe ratios (<0.11), but the Mattaia Formation has an elevated median Mn/Fe ratio of 0.28. This could suggest that the Mattaia Formation was deposited under less reducing (i.e., manganous) conditions compared to the underlying Ediacaran units. Based on the profound sulfur isotope event recorded in the Khatyspyt Formation, ref. 20 suggested locally euxinic conditions at the base of the interval, and a transition to non-euxinic conditions when ‘superheavy pyrite’ appears in the stratigraphic record. Our data further constrain local Khatyspyt redox conditions, suggesting that deposition of the entire succession occurred under anoxic conditions and that the δ34S data may indicate a local shift from euxinic to ferruginous conditions (not discernable using Ce anomalies) or a shift in global sulfate availability. Regardless, our Ce anomaly data from Olenek Uplift carbonates strongly suggest deposition beneath an anoxic water column through the entirety of the succession.

Fig. 3. Rare-earth element and δ238U comparison.

A Rare-earth element + yttrium (REY) spider plots for average Olenek Uplift samples (orange; this study), average Nama Group samples that were investigated for U isotopes (blue; ref. 18), and average South China samples that were investigated for U isotopes (green; ref. 17). REY concentrations are normalized to post-Archean Australian shale (PAAS) values. For the Olenek Uplift and Namibian sections, only those samples with Y/Ho ratios >36 were included (no Y/Ho data are available for the South China section). Oxygenated North Pacific seawater at 400 m depth44 is plotted for comparison, along with the shallowest depth sample with Y/Ho > 36 from Pleistocene carbonate platform cores in the Bahamas49. Highlighted in gray is Ce, showing the presence/absence of a negative Ce anomaly, and Y, showing the positive Y anomaly that indicates a seawater signal. B Cross-plot of Ce/Ce* vs. δ238U for samples from this study (orange), Namibia (blue; ref. 18), and South China (green; ref. 17). Modern Bahamas median δ238U value is from ref. 55 and oxic/anoxic Ce/Ce* cutoff value of 0.9 is from ref. 21.

Uranium isotopes

On a global scale, U isotope abundances in carbonates have been used recently to assess the extent of euxinic water masses, which today only occupy around 0.05% of the ocean floor, primarily in the Black Sea, Cariaco Basin, and Norwegian fjords. Under such euxinic conditions, isotopically heavy U(IV) is preferentially removed to sediments, leaving residual seawater U(VI) enriched in the light 235U isotope. The median δ238U value for syn-depositional and post-depositional Bahamian carbonates deposited in the well-oxygenated modern oceans is −0.15‰55, such that lower values recorded in ancient carbonates likely indicate an expansion of global marine euxinia compared to today. In our sample set, the median δ238U value is −0.58‰ in the Maastakh Formation, −0.64‰ in the Khatyspyt Formation, −0.57‰ in the Turkut Formation, and −0.53‰ in the Mattaia Formation (average analytical uncertainty = ±0.08‰ 2 s.d. based on replicate measurements). The dataset as a whole has a median δ238U value of −0.58‰, which is significantly lower than modern carbonates (Supplementary Fig. 9), indicating widespread marine euxinia during the terminal Ediacaran Period and additionally during Cambrian Stage 2. Our Olenek δ238U values are similar to those recorded in terminal Ediacaran sections from Namibia (median = −0.77‰)18 and South China (median = −0.87‰)17,59 (Supplementary Fig. 10). We attribute the slightly heavier δ238U values in the Olenek Uplift to differences in local redox environments where Ce/Ce* data indicate that the Olenek Uplift was deposited under anoxic conditions, the Namibian sections under mixed conditions18,21, and the South China sections under oxic conditions17,59 (Fig. 3). Uranium isotopes recorded under anoxic/euxinic pore water conditions tend to be enriched in the heavier isotope by ~0.3‰ as compared to coeval seawater55,60, which matches the offset between the anoxic Olenek Uplift and oxic South China records. The oxic South China section would be expected to more closely capture global seawater δ238U compositions, and the more negative values there (down to −1.2‰) are the lightest recorded thus far in the geological archive, including those measured in multiple sections across the Permo-Triassic boundary during which anoxia is thought to be a primary driver of the largest Phanerozoic extinction event61–65 (Supplementary Fig. 9). These integrated observations support the view that the terminal Ediacaran oceans, where the Ediacara biotas evolved and thrived, were more reducing than at any other time in Earth history thus far investigated using U isotopes.

Discussion

Despite our carbonate-based determinations of pervasive positive Ce anomalies indicative of anoxic depositional conditions in the Olenek basin, the Khatyspyt Formation contains a diverse array of Ediacaran macrofossils preserved in situ (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). This includes Nenoxites curvus, a rangeomorph Charnia masoni, an arboreomorph Khatyspytia grandis, macrophytes, and various holdfast structures34. The combination of in situ Ediacaran macrofossils and geochemical data suggesting a locally reducing water column is strong evidence that this Ediacaran assemblage was living under anoxic conditions. Whereas basal, sessile metazoans have a lower oxygen demand than large, motile animals66,67, all animals require some oxygen for their metabolism, with the only possible exception being meiofaunal loriciferans living permanently in the absence of molecular oxygen68,69, although the true oxygen demand of these organisms is still debated70,71. The absence of a negative Ce anomaly in Olenek basin waters suggests the lack of Mn-oxidation, which occurs in modern environments at sub-micromolar oxygen concentrations (3 μM or less)46. Bilaterians have been recorded in modern environments at O2 concentrations as low as ~1 μM, which ref. 72 suggests is near the theoretical limit needed to support these animals. It is possible, then, that members of the Khatyspyt Ediacaran assemblage were metazoans able to survive under lower O2 conditions than are needed to generate a negative Ce anomaly. These exceedingly low O2 concentrations would severely limit the size and metabolic rate of metazoans, however, which is inconsistent with the macroscopic size of the Khatyspyt fossils (although this depends on body construction and may not apply to some diploblasts). The sub-micromolar O2 living conditions of the Khatyspyt Ediacaran assemblage suggest instead that these organisms may not have metazoan affinities, unless they developed special adaptations to permanently anoxic conditions (e.g., the use of hydrogenosome-like organelles instead of mitochondria in their anaerobic metabolic cycle)68. Another intriguing possibility is that this Ediacaran assemblage lived in association with epibiotic or endosymbiotic bacteria8,10, by analogy with recent metazoans persisting at very low oxygen levels of only a few micromolar per kg73–76.

Alternatively, it is important to consider the possibility that our recorded Ce/Ce* values represent a time-averaged signal that is not responding on the same time scale as local ecological change. For example, ref. 40 reported Ediacaran body fossils and, importantly, clear bilaterian trace fossils from shales that record an anoxic iron speciation signal in northwestern Canada. Additionally, ref. 77 investigated a core through the organic-rich Cambrian Alum Shale in Bornholm, Denmark and found that the presence of benthic fauna (e.g., trilobites, brachiopods) can be tied to brief (<3000 year) episodes of seafloor oxygenation that occurred despite an overall anoxic geochemical signature recorded for this unit. It therefore possible, then, that the Khatyspyt soft-bodied Ediacara assemblage colonized the seafloor during brief periods of oxygenation in environments that were frequently impinged upon by anoxic waters. In modern systems, ecological recovery by macrofauna after hypoxic or anoxic episodes typically occurs on the order of several years78, and in environments with seasonal hypoxia or anoxia, metazoan colonization similarly responds on seasonal scales79,80. Regardless of this possibility, our data demonstrate that some members of the soft-bodied Ediacara biota were well-adapted to environments with low and fluctuating oxygen levels. The potential for physiological tolerance of frequent anoxia is supported by the suggestion that ancestral eukaryotes were facultatively anaerobic and that obligate aerobiosis is a derived trait81,82. If a facultatively anaerobic lifestyle was more widespread in early eukaryotes, it is reasonable that some Ediacaran organisms had greater tolerance of fluctuating redox conditions within generally low-oxygen environments.

The U isotope data from several terminal Ediacaran basins are consistent across space and time, suggesting expanded euxinia in the world oceans (most likely along productive continental margins) associated with the evolution and diversification of Ediacaran macroorganisms. Despite the spread of H2S-rich water masses, the Ediacara biota persisted on several continental margins up until the Ediacaran-Cambrian boundary, including a substantial diversity of Erniettomorph and Rangeomorph taxa83. This suggests that Ediacaran communities could have existed in oxic refugia above anoxic and potentially euxinic water masses, or that some members of the Ediacaran macrobiota were tolerant of low-oxygen conditions, or both. Our Ce/Ce* data from the Olenek Uplift clearly show a diverse assemblage of Ediacaran macroorganisms preserved in a setting that was often anoxic, thus supporting their low-oxygen tolerance.

Our data for both local and global redox conditions also shed light on the anomalous behavior of the terminal Ediacaran sulfur cycle. 34S-enriched pyrite (in which the sulfur isotopic composition matches or even exceeds that of carbonate-associated sulfate [CAS] or bedded sulfates) is seen in multiple Ediacaran successions worldwide, including in northwestern China41,84, South China36, Namibia39,42, northwestern Canada40, and Oman38. Various explanations for the ‘superheavy pyrite’ have come forth, but none of them have addressed the issue in the framework of prolonged late Ediacaran euxinia. As documented in the δ238U compositions of Ediacaran carbonates, the oxygenation state of the oceans oscillated between oxic and anoxic states. Following δ238U evidence for ocean ventilation (oxidation) during the Shuram negative δ13C excursion13, the subsequent terminal Ediacaran nadir of δ238U values is associated with expanded post-Shuram ocean euxinia and positive δ13C anomalies recorded in both South China and arctic Siberia. This coupling supports the canonical interpretation of δ13C fluctuations as resulting from enhanced burial and sequestration of organic matter in the global ocean85,86, which is promoted under conditions of expanded anoxia. This interval also reveals a profound stratigraphic step up (>40‰) in the δ34S signature of pyrite, with stratigraphic trends in multiple sections rising to values that meet and exceed those of seawater sulfate. Such a phenomenon requires removal of 32S from the oceans through the microbial production of H2S and its burial as insoluble pyrite in sediments when soluble iron is available. The mixing of globally expanded euxinic waters (as evidenced by the exceptionally light carbonate δ238U values) with ferruginous waters that may have still dominated the deep Ediacaran oceans87 provides a biogeochemical mechanism for the starvation of sulfate in the ocean (resulting in 34S enrichment of the residual mass) after the Shuram Excursion and before the Ediacaran-Cambrian boundary. These observations contrast with δ238U and δ34S evidence for greater oxygenation with higher sulfate and alkalinity in seawater associated with the earlier Shuram Excursion13,88,89, as well as across the subsequent Ediacaran-Cambrian transition, when bedded sulfates are recognized worldwide38,59. This geochemical and lithological worldview further highlights the oscillatory redox landscape of the Ediacaran Period.

The emerging picture of Ediacaran redox trends is further consistent with a spike in redox-sensitive trace metal concentrations in euxinic shales at ~560 Ma, which was interpreted by ref. 15 as an oceanic oxygenation event, although an alternative explanation involving Mn oxide shuttling has been proposed90. This metal enrichment event was followed by a return to crustal values in the terminal Ediacaran Period, with another oxygenation event occurring at ~540 Ma. Together, widespread oceanic euxinia in the terminal Ediacaran Period can explain: (1) positive carbonate δ13C values promoted by enhanced organic carbon burial; (2) anomalously light carbonate δ238U values; (3) ‘superheavy pyrite’ δ34S values caused by seawater sulfate distillation; and (4) muted trace metal enrichments in euxinic shales caused by drawdown of the oceanic metal inventory. By contrast, oxygenation during the preceding Shuram Excursion and across the subsequent Ediacaran-Cambrian boundary was accompanied by negative carbonate δ13C values, near-modern carbonate δ238U values, 34S-depleted pyrites, and Phanerozoic-style trace metal enrichments.

After widespread terminal Ediacaran euxinia and potential re-oxygenation across the Ediacaran-Cambrian transition associated with the accumulation of thick sulfate deposits worldwide38, ref. 59 found δ238U evidence for a second euxinic pulse in Cambrian Stage 2. In addition, ref. 91 found two pulses of expanded anoxia—one at the beginning of and one within Cambrian Stage 2 based on δ238U data. Our δ238U data from the biostratigraphically constrained Mattaia carbonate platform are consistent with the expansion of ocean euxinia at this time. In addition, our Ce/Ce* data further indicate locally anoxic water column conditions. SSFs preserved in the Mattaia Formation reveal evidence of transport and are not found in situ, possibly indicating that these animals were living in shallower shelf and shoreface environments (where a small, oxygenated layer existed above the chemocline) and then transported offshore. A shift back to a strongly euxinic ocean in Cambrian Stage 2 could have slowed the emergence of complex Cambrian life after its initial proliferation during the more oxygenated Fortunian Stage. Frequent redox oscillation has also been invoked as a driver of animal diversification beginning in Cambrian Stage 292. Alternatively, the persistence of euxinia in the global ocean—as indicated by light δ238U values—through the studied Olenek Uplift section could indicate that redox conditions were only a minimal factor in controlling the evolution of early complex life on Earth. These results are consistent with a compilation of shale iron speciation data that suggest only limited oxygenation across the Neoproterozoic-Phanerozoic transition93, with more permanent ocean oxygenation perhaps delayed until the Devonian Period94–98.

In summary, this study combines proxy evidence for both local and global redox conditions with paleontological observations of a diverse assemblage of Ediacaran macroorganisms preserved in carbonate rocks of the Olenek Uplift of arctic Siberia. Our data indicate that: (1) a wide array of Ediacaran macroorganisms are preserved in environments that were often anoxic, and (2) the Ediacaran macrobiota persisted on multiple continental margins through a period of widespread ocean euxinia. Our δ238U data are comparable to other coeval terminal Ediacaran sections worldwide, indicating that ocean euxinia was more widespread than at any other interval in Earth history examined to date using U isotopes. Evidence of local anoxia recorded in strata that preserve Ediacaran organisms in situ, combined with strongly euxinic terminal Ediacaran oceans as indicated by global U isotope data, strongly suggests that some members of the Ediacaran macrobiota were tolerant of low-oxygen conditions and might have been capable of a facultatively anaerobic lifestyle. One intriguing possibility is that Ediacaran organisms used chemolithoautotrophy (e.g., sulfide oxidation) either directly or through symbionts, exploiting redox gradients at the sediment-water interface. Alternatively, these soft-bodied Ediacara organisms might have colonized the seafloor during brief oxygenation episodes not recorded by local redox proxy data. Ultimately, our combination of local and global redox data with Ediacaran fossils in the same succession offers an integrated perspective on the relationship between ocean redox and the evolution of early macroscopic life on Earth.

Methods

Sample collection and preparation

Samples were collected during a 2009–2010 field expedition to the Khorbusuonka and Olenek river areas of arctic Siberia. Hand samples were collected, cut, and bulk powders created in Russia before being transported to the United States. Samples were previously analyzed for a variety of geochemical proxies by refs. 20, 99, and from these preliminary data, samples were selected for this study based mostly on wt.% carbonate, with high carbonate content being essential for reliable Ce anomaly and U isotope results. 56 of the purest carbonate samples (>75 wt.%) over 497.5 m of composite section were selected for analysis in this study.

Petrography

Thin sections were prepared by Vancouver Petrographics for a select group of samples and analyzed using a standard petrographic microscope in plane- and cross-polarized light in order to understand diagenesis. Diagenetic pathways were assessed by visual inspection of the degree of fabric retention, and petrographic characteristics were compared to geochemical data in order to interpret the diagenetic history of the succession.

Major and trace elements

50 mL centrifuge tubes were rinsed with 6 M HCl and Milli-Q water prior to adding powdered samples. Approximately 1.5 g of sample powder was first digested by 15 mL of 1 M HNO3, followed by 5 mL of concentrated HNO3, and finally, 20 additional mL of 1 M HNO3. Each sample was shaken and subject to vortex mixing to ensure all powder had reacted with acid. Samples were left to sit for 24 h at room temperature to allow for maximum carbonate dissolution. Digests were centrifuged at 3800 rpm for 9 min and the supernatant was decanted from the residue. 200 to 350 mL of the supernatant was removed, placed into 10 mL centrifuge tubes, diluted to ~200 ppm calcium (Ca) with 2% HNO3, and analyzed for a full suite of major and trace element concentrations on a Thermo iCAP™ quadrupole inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (Q-ICP-MS) at Arizona State University. Typical precision is reported based on repeated analysis of simultaneously run standards, and in this study, relative % s.d. was <6% for all reported elements. Total U concentrations were also analyzed using an Element-2 ICP-MS at the University of Maryland. Analytical precision was better than 3% based on duplicate analyses.

Rare-earth elements

Rare-earth elements were extracted using a multi-step leaching process. For calcite samples, the first 20% of moles of CaCO3 were dissolved with the appropriate amount of 2% HNO3. The insoluble residue was then separated by centrifugation and the solution decanted and disposed. The next 40% of moles of CaCO3 were then dissolved using the appropriate amount of 2% HNO3 and centrifuged again. The solution was pipetted, diluted to 10 mL with 2% HNO3, and shipped to Arizona State University for elemental analysis by Q-ICP-MS. For dolomite samples, a one step of digestion, which dissolves the first 20% of moles of CaMg(CO3)2 in the appropriate amount of 2% HNO3 was utilized. This multi-step digestion process follows the methods suggested by ref. 48 for retrieving the most seawater-like REE data. Typical precision is reported based on repeated analysis of simultaneously run standards, and in this study, relative % s.d. was better than 4% for all REEs. Associated element Y was run using a separate calibration standard. Duplicate sample analyses for Y reported an average s.d. of ± 0.24 ppm. REE concentrations were normalized to the post-Archean Australian shale (PAAS) standard100 and the cerium anomaly (Ce/Ce*) was calculated using: Ce/Ce* = [Ce]SN/([Pr]SN2/[Nd]SN) where SN denotes a PAAS-normalized value48.

Uranium isotopes

The remaining solution that was not used for major and trace element analysis was dried down in clean Teflon beakers for U isotope analysis. An appropriate amount of Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements (IRMM) 236U/233U double-spike (0.8 mL of spike per 500 ng U) was added to each sample before U isotope column chemistry101. The samples were digested sequentially using reverse aqua regia, H2O2, and concentrated HNO3. The spiked samples were evaporated to dryness and re-dissolved in 3 M HNO3. Uranium was separated twice from matrix elements by ion exchange chromatography using UTEVA resin. Separated U was dissolved in 2% HNO3 to a concentration of 40–50 ppb and analyzed on Thermo Scientific Neptune multi-collector ICP-MS instruments at Arizona State University and the University of Maryland (see Supplementary Fig. 13 for inter-laboratory comparison). The standard solution CRM 145 (50 ppb U) was analyzed once every two samples. A secondary standard (CRM 129a) was also analyzed after every ten analyses. Sample δ238U values were normalized to the average of bracketing standard CRM 145. Precision of standards and duplicate analyses is reported as 2 s.d. of replicate measurements. Average precision for the sample set is ±0.08‰. Methods are adapted from ref. 53 and further details can be found in refs. 61, 101.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Tyler Goepfert, Trevor Martin, and Gwyneth Gordon at Arizona State University, as well as Richard Ash at the University of Maryland, for analytical support. G.J.G. is indebted to Ariel Anbar at Arizona State University for use of instrumentation, and also thanks the NASA Postdoctoral Program and the College of Science Seed Grant Program at George Mason University for financial support. This project was supported by a National Science Foundation (NSF) Geobiology and Low-Temperature Geochemistry Program grant (Award Numbers 2020644 and 2020593) to A.J.K. and G.J.G. This project was also supported by Russian Science Foundation grant 20-67-46028 to D.V.G.

Author contributions

L.B.C. performed all wet chemical laboratory procedures; wrote an initial draft of the manuscript in collaboration with G.J.G. G.J.G designed the research; trained L.B.C. in laboratory procedures; performed mass spectrometry analysis; supervised and contributed to the initial manuscript draft; rewrote and edited the manuscript before submission; revised the manuscript based on reviewer and editor comments; provided funding. D.V.G. performed fieldwork; provided samples; heavily contributed to writing and editing the manuscript before submission. S.J.R. facilitated successful mass spectrometry analysis through guidance on procedures and methods. A.J.M. performed all U-Pb zircon analysis; wrote portion of the Supplementary Information related to U-Pb zircon analysis. A.J.K. designed the research; performed fieldwork; provided samples; mentored L.B.C.; performed mass spectrometry analysis; contributed to the initial manuscript draft; edited the manuscript before submission; provided funding.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Fred Bowyer and Erik Sperling for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

All data generated in this study are available in Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Data 2.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Lucas B. Cherry, Email: lucasbcherry1@gmail.com

Geoffrey J. Gilleaudeau, Email: ggilleau@gmu.edu

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-022-35012-y.

References

- 1.Dunn, F. S. et al. The developmental biology of Charnia and the eumetazoan affinity of the Ediacaran rangeomorphs. Sci. Adv.10.1126/sciadv.abe0291 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Narbonne GM. The Ediacara Biota: neoproterozoic origin of animals and their ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2005;33:421–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev.earth.33.092203.122519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell EG, Kenchington CG, Liu AG, Matthews JJ, Butterfield NJ. Reconstructing the reproductive mode of an Ediacaran macro-organism. Nature. 2015;524:343–346. doi: 10.1038/nature14646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMenamin M. Osmotrophy in fossil protoctists and early animals. Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 1993;23:165–166. doi: 10.1080/07924259.1993.9672308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhuravlev AY. Were Ediacaran Vendobionta multicellulars? Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie. Abhandlungen. 1993;190:299–314. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laflamme M, Xiao S, Kowalewski M. Osmotrophy in modular Ediacara organisms. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:14438–14443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904836106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sperling EA, Peterson KJ, Laflamme M. Rangeomorphs, Thectardis (Porifera?) and dissolved organic carbon in the Ediacaran oceans. Geobiology. 2011;9:24–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2010.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaufman, A. J. In Chemostratigraphy Across Major Chronological Boundaries (eds Sial, A. N., Gaucher, C., Ramkumar, M. & Ferreira, V. P.) 10.1002/9781119382508.ch7 (American Geophysical Union, 2019).

- 9.Butterfield, N. J. Constructional and functional anatomy of Ediacaran rangeomorphs. Geol. Magazine10.1017/S0016756820000734 (2020).

- 10.McIlroy, D., Dufour, S. C., Taylor, R. & Nicholls, R. The role of symbiosis in the first colonization of the seafloor by macrobiota: insights from the oldest Ediacaran biota (Newfoundland, Canada). Biosystems205, 104413 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Hoyal Cuthill JF, Conway Morris S. Fractal branching organizations of Ediacaran rangeomorph fronds reveal a lost Proterozoic body plan. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:13122–13126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408542111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canfield DE, Poulton SW, Narbonne GM. Late-Neoproterozoic deep-ocean oxygenation and the rise of animal life. Science. 2007;315:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.1135013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang F, et al. Global marine redox changes drove the rise and fall of the Ediacara biota. Geobiology. 2019;17:594–610. doi: 10.1111/gbi.12359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahoo SK, et al. Ocean oxygenation in the wake of the Marinoan glaciation. Nature. 2012;489:546–549. doi: 10.1038/nature11445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sahoo SK, et al. Oceanic oxygenation events in the anoxic Ediacaran ocean. Geobiology. 2016;14:457–468. doi: 10.1111/gbi.12182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kendall B, et al. Uranium and molybdenum isotope evidence for an episode of widespread ocean oxygenation during the late Ediacaran Period. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta. 2015;156:173–193. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2015.02.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang F, et al. Extensive marine anoxia during the terminal Ediacaran Period. Sci. Adv. 2018;4:1–11. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aan8983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tostevin R, et al. Uranium isotope evidence for an expansion of anoxia in terminal Ediacaran oceans. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2019;506:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2018.10.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li C, et al. Ediacaran marine redox heterogeneity and early animal ecosystems. Nat. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:17097. doi: 10.1038/srep17097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cui H, et al. Redox-dependent distribution of early macro-organisms: evidence from the terminal Ediacaran Khatyspyt Formation in Arctic Siberia. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2016;461:122–139. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tostevin R, et al. Effective use of cerium anomalies as a redox proxy in carbonate-dominated marine settings. Chem. Geol. 2016;438:146–162. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2016.06.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowyer FT, Wood RA, Poulton SW. Controls on the evolution of Ediacaran metazoan Ecosystems: a redox perspective. Geobiology. 2017;15:516–551. doi: 10.1111/gbi.12232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bykova N, Gill BC, Grazhdankin D, Rogov V, Xiao S. A geochemical study of the Ediacaran discoidal fossil Aspidella preserved in limestones: Implications for its taphonomy and paleoecology. Geobiology. 2017;15:572–587. doi: 10.1111/gbi.12240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennett WW, Canfield DE. Redox-sensitive trace metals as paleoredox proxies: a review and analysis of data from modern sediments. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020;204:103175. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knoll AH, Grotzinger JP, Kaufman AJ, Kolosov P. Integrated approaches to terminal Proterozoic stratigraphy: an example from the Olenek Uplift, north-eastern Siberia. Precambrian Res. 1995;73:251–270. doi: 10.1016/0301-9268(94)00081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pelechaty SM, Kaufman AJ, Grotzinger JP. Evaluation of δ13C chemostratigraphy for intrabasinal correlation: Vendian strata of northeast Siberia. GSA Bull. 1996;108:992–1003. doi: 10.1130/0016-7606(1996)108<0992:EOCCFI>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagovitsin KE, et al. Revised Neoproterozoic and Terreneuvian stratigraphy of the Lena-Anabar Basin and north-western slope of the Olenek Uplift, Siberian platform. Precambrian Res. 2015;270:226–245. doi: 10.1016/j.precamres.2015.09.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grazhdankin DV, et al. Quo vadis, Tommotian? Geol. Mag. 2020;157:22–34. doi: 10.1017/S0016756819001286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bowyer FT, et al. Calibrating the temporal and spatial dynamics of the Ediacaran-Cambrian radiation of animals. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2022;225:103913. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowring S, et al. Calibrating rates of early Cambrian evolution. Science. 1993;261:1293–1298. doi: 10.1126/science.11539488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linnemann U, et al. New high-resolution age data from the Ediacaran-Cambrian boundary indicate rapid, ecologically driven onset of the Cambrian explosion. Terra Nova. 2019;31:49–58. doi: 10.1111/ter.12368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson LL, et al. Pushing the boundary: a calibrated Ediacaran-Cambrian stratigraphic record from the Nama Group in northwestern Republic of South Africa. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2022;580:117396. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2022.117396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaufman, A. J. et al. A Shorter Fuse For The Cambrian Explosion? Geological Society of America Annual Meeting (Charlotte, 2012).

- 34.Grazhdankin DV, Balthasar U, Nagovitsin KE, Kochnev BB. Carbonate-hosted Avalon-type fossils in arctic Siberia. Geology. 2008;36:803–806. doi: 10.1130/G24946A.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cui H, et al. Environmental context for the terminal Ediacaran biomineralization of animals. Geobiology. 2016;14:344–363. doi: 10.1111/gbi.12178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cui H, et al. Sedimentology and chemostratigraphy of the terminal Ediacaran Dengying Formation at the Gaojiashan section, South China. Geol. Mag. 2019;156:1924–1948. doi: 10.1017/S0016756819000293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu MY, Babcock LE, Peng SC. Advances in Cambrian stratigraphy and paleontology: Integrating correlation techniques, paleobiology, taphonomy and paleoenvironmental reconstruction. Palaeoworld. 2006;15:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.palwor.2006.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fike D, Grotzinger J. A paired sulfate–pyrite δ34S approach to understanding the evolution of the Ediacaran–Cambrian sulfur cycle. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta. 2008;72:2636–2648. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2008.03.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ries JB, Fike DA, Pratt LM, Lyons TW, Grotzinger JP. Superheavy pyrite (δ34Spyr > δ34SCAS) in the terminal Proterozoic Nama Group, southern Namibia: a consequence of low seawater sulfate at the dawn of animal life. Geology. 2009;37:743–746. doi: 10.1130/G25775A.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sperling EA, et al. Oxygen, facies, and secular controls on the appearance of Cryogenian and Ediacaran body and trace fossils in the Mackenzie Mountains of northwestern Canada. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2016;128:558–575. doi: 10.1130/B31329.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen B, Xiao S, Zhou C, Kaufman AJ, Yuan X. Carbon and sulfur isotope chemostratigraphy of the Neoproterozoic Quangi Group of the Chaidam Basin, NW China: Basin stratification in the aftermath of an Ediacaran glaciation postdating the Shuram event? Precambrian Res. 2010;177:241–252. doi: 10.1016/j.precamres.2009.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tostevin R, et al. Constraints on the late Ediacaran sulfur cycle from carbonate associated sulfate. Precambrian Res. 2017;290:113–125. doi: 10.1016/j.precamres.2017.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cui H, et al. Questioning the biogenicity of Neoproterozoic superheavy pyrite by SIMS. Am. Mineralogist. 2018;103:1362–1400. doi: 10.2138/am-2018-6489. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alibo DS, Nozaki Y. Rare earth elements in seawater: particle association, shale-normalization, and Ce oxidation. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta. 1999;63:363–372. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(98)00279-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tostevin, R. Cerium anomalies and paleoredox. Elements in Geochemical Tracers in Earth System Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2021).

- 46.Clement BG, Luther GW, III, Tebo BM. Rapid, oxygen-dependent microbial Mn(II) oxidation kinetics at sub-micromolar oxygen concentrations in the Black Sea suboxic zone. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta. 2009;73:1878–1889. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2008.12.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao Y, et al. A review of retrieving pristine rare earth element signatures from carbonates. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol., Palaeoecol. 2022;586:110765. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2021.110765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tostevin, R. et al. Low-oxygen waters limited habitable space for early animals. Nat. Commun.10.1038/ncomms12818 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Liu XM, Hardisty DS, Lyons TW, Swart PK. Evaluating the fidelity of the cerium paleoredox tracer during variable carbonate diagenesis on the Great Bahamas Bank. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta. 2019;248:25–42. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2018.12.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tissot FL, Dauphas N. Uranium isotopic compositions of the crust and ocean: age corrections, U budget and global extent of modern anoxia. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta. 2015;167:113–143. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2015.06.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cole DB, et al. Uranium isotope fractionation in non-sulfidic anoxic settings and the global uranium isotope mass balance. Glob. Biogeochemical Cycles. 2020;34:e2020BG006649. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bruggmann S, et al. Uranium isotope cycling on the highly productive Peruvian margin. Chem. Geol. 2022;590:120705. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2021.120705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gilleaudeau GJ, et al. Uranium isotope evidence for limited euxinia in mid-Proterozoic oceans. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2019;521:150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2019.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lau KV, et al. Variable local basin hydrography and productivity control the uranium isotope paleoredox proxy in anoxic black shales. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta. 2022;317:433–456. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2021.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen X, et al. Diagenetic effects on uranium isotope fractionation in carbonate sediments from the Bahamas. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta. 2018;237:294–311. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2018.06.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaufman AJ, Knoll AH. Neoproterozoic variations in the C-isotopic composition of seawater: Stratigraphic and biogeochemical implications. Precambrian Res. 1995;73:27–49. doi: 10.1016/0301-9268(94)00070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gilleaudeau GJ, Kah LC. Carbon isotope records in a Mesoproterozoic epicratonic sea: Carbon cycling in a low-oxygen world. Precambrian Res. 2013;228:85–101. doi: 10.1016/j.precamres.2013.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Banner JL, Hanson GN. Calculation of simultaneous isotopic and trace element variations during water-rock interaction with applications to carbonate diagenesis. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta. 1990;54:3123–3137. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(90)90128-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wei G-Y, et al. Marine redox fluctuation as a potential trigger for the Cambrian explosion. Geology. 2018;46:587–590. doi: 10.1130/G40150.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Romaniello SJ, Herrmann AD, Anbar AD. Uranium concentrations and 238U/235U isotope ratios in modern carbonates from the Bahamas: Assessing a novel paleoredox proxy. Chem. Geol. 2013;362:305–316. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2013.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brennecka GA, Herrmann AD, Algeo TJ, Anbar AD. Rapid expansion of oceanic anoxia immediately before the end-Permian mass extinction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:17631–17634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106039108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lau KV, et al. Marine anoxia and delayed Earth system recovery after the end-Permian extinction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:2360–2365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515080113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Elrick M, et al. Global-ocean redox variation during the middle-late Permian through Early Triassic based on uranium isotope and Th/U trends of marine carbonates. Geology. 2017;45:163–166. doi: 10.1130/G38585.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang F, et al. Congruent Permian-Triassic δ238U records at Panthalassic and Tethyan sites: confirmation of global-oceanic anoxia and validation of the U-isotope paleoredox proxy. Geology. 2018;46:327–330. doi: 10.1130/G39695.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang F, et al. Multiple episodes of extensive marine anoxia linked to global warming and continental weathering following the latest Permian mass extinction. Sci. Adv. 2018;4:e1602921. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1602921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sperling EA, et al. Oxygen, ecology, and the Cambrian radiation of animals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:13446–13451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312778110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mills DB, et al. Oxygen requirements of the earliest animals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:4168–4172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400547111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Danovaro R, et al. The first metazoa living in permanently anoxic conditions. BMC Biol. 2010;8:30. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Danovaro R, et al. The challenge of proving the existence of metazoan life in permanently anoxic deep-sea sediments. BMC Biol. 2016;14:43. doi: 10.1186/s12915-016-0263-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bernhard JM, et al. Metazoans of redoxcline sediments in Mediterranean deep-sea hypersaline anoxic basins. BMC Biol. 2015;13:105. doi: 10.1186/s12915-015-0213-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mentel M, Tielens AGM, Martin WF. Animals, anoxic environments, and reasons to go deep. BMC Biol. 2016;14:44. doi: 10.1186/s12915-016-0266-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sperling EA, Halverson GP, Knoll AH, Macdonald FA, Johnston DT. A basin redox transect at the dawn of animal life. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2013;371–372:143–155. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2013.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bernhard JM, Buck KR, Farmer MA, Bowser SS. The Santa Barbara Basin is a symbiosis oasis. Nature. 2000;403:77–80. doi: 10.1038/47476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dubilier N, et al. Endosymbiotic sulphate-reducing and sulphide-oxidizing bacteria in an oligochaete worm. Nature. 2001;411:298–302. doi: 10.1038/35077067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Levin LA, Rathburn AE, Gutierrez D, Munoz P, Shankle A. Bioturbation by symbiont-bearing annelids in near-anoxic sediments: Implications for biofacies models and paleo-oxygen assessments. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2003;199:129–140. doi: 10.1016/S0031-0182(03)00500-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tunnicliffe, V., Juniper, S. K. & Sibuet, M. In Ecosystems of The Deep Oceans (ed. Tyler P. A.) 81–110 (Elsevier, 2003).

- 77.Dahl TW, et al. Brief oxygenation events in locally anoxic oceans during the Cambrian solves the animal breathing paradox. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48123-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Levin L, et al. Effects of natural and human-induced hypoxia on coastal benthos. Biogeosci. Discuss. 2009;6:3563–3654. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Levin LA, Whitcraft CR, Mendoza GF, Gonzalez JP, Cowie G. Oxygen and organic matter thresholds for benthic faunal activity on the Pakistan margin oxygen minimum zone (700–1100 m) Deep-Sea Res., Part II, Topical Stud. Oceanogr. 2009;56:449–471. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2008.05.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Matabos M, Tunnicliffe V, Juniper SK, Dean C. A year in hypoxia: Epibenthic community responses to severe oxygen deficit at a subsea observatory in a coastal inlet. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mentel M, Röttger M, Leys S, Tielens AGM, Martin WF. Of early animals, anaerobic mitochondria, and a modern sponge. BioEssays. 2014;36:924–932. doi: 10.1002/bies.201400060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mills DB, et al. Eukaryogenesis and oxygen in Earth history. Nat. Ecol. Evolution. 2022;6:520–532. doi: 10.1038/s41559-022-01733-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Darroch SA, Smith EF, Laflamme M, Erwin DH. Ediacaran extinction and Cambrian explosion. Trends Ecol. Evolution. 2018;33:653–663. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shen B, et al. Carbon, sulfur, and oxygen isotope evidence for a strong depth gradient and oceanic oxidation after the Ediacaran Hankalchough glaciation. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta. 2011;75:1357–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2010.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Broecker WS. A boundary condition on the evolution of atmospheric oxygen. J. Geophys. Res. 1970;75:3553–3557. doi: 10.1029/JC075i018p03553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hayes JM. Practice and principles of isotopic measurements in organic geochemistry. Org. Geochem. Contemporaneous Anc. Sediment. 1983;5:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Huang J, et al. A predominantly ferruginous condition in the Ediacaran deep ocean: Geochemistry of black shales in the Ediacaran Doushantuo Formation, South China. Precambrian Res. 2017;295:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.precamres.2017.04.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fike DA, Grotzinger JP, Pratt LM, Summons RE. Oxidation of the Ediacaran ocean. Nature. 2006;444:744–747. doi: 10.1038/nature05345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cui H, Kaufman AJ, Xiao S, Zhou C, Liu X-M. Was the Ediacaran Shuram Excursion a globally synchronized early diagenetic event? Insights from methane-derived authigenic carbonates in the uppermost Doushantuo Formation, South China. Chem. Geol. 2017;450:59–80. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2016.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ostrander CM, et al. Multiple negative molybdenum isotope excursions in the Doushantuo Formation (South China) fingerprint complex redox-related processes in the Ediacaran Nanhua Basin. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta. 2019;261:191–209. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2019.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dahl TW, et al. Atmosphere-ocean oxygen and productivity dynamics during early animal radiations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:19352–19361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1901178116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.He T, et al. Possible links between extreme oxygen perturbations and the Cambrian radiation of animals. Nat. Geosci. 2019;12:468–474. doi: 10.1038/s41561-019-0357-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sperling EA, et al. Statistical analysis of iron geochemical data suggests limited late Proterozoic oxygenation. Nature. 2015;523:451–454. doi: 10.1038/nature14589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dahl TW, et al. Devonian rise in atmospheric oxygen correlated to the radiations of terrestrial plants and large predatory fish. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:17911–17915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011287107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lenton TM, et al. Earliest land plants created modern levels of atmospheric oxygen. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:9704–9709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604787113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wallace MW, et al. Oxygenation history of the Neoproterozoic to early Phanerozoic and the rise of land plants. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2017;466:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2017.02.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lu W, et al. Late inception of a resiliently oxygenated upper ocean. Science. 2018;361:174–177. doi: 10.1126/science.aar5372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Elrick M, et al. Major Early-Middle Devonian oceanic oxygenation linked to early land plant evolution detected using high-resolution U isotopes of marine limestones. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2022;581:117410. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2022.117410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Peek, S. Geochemical and Radiometric Constraints on the Redox History of Late Ediacaran Oceans (University of Maryland, 2012).

- 100.Taylor, S. R. & McLennan, S. M. The Continental Crust: Its Composition and Evolution (Wiley–Blackwell, 1985).

- 101.Weyer S, et al. Natural fractionation of 238U/235U. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta. 2008;72:345–359. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2007.11.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Scotese CR. An atlas of paleogeographic maps: the seas come in and the seas go out. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2021;49:669–718. doi: 10.1146/annurev-earth-081320-064052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Maloof AC, et al. The earliest Cambrian record of animals and ocean geochemical change. GSA Bull. 2010;122:1731–1774. doi: 10.1130/B30346.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

All data generated in this study are available in Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Data 2.