Abstract

The combined catalytic systems derived from organocatalysts and transition metals exhibit powerful activation and stereoselective-control abilities in asymmetric catalysis. This work describes a highly efficient chiral aldehyde-nickel dual catalytic system and its application for the direct asymmetric α−propargylation reaction of amino acid esters with propargylic alcohol derivatives. Various structural diversity α,α−disubstituted non-proteinogenic α−amino acid esters are produced in good-to-excellent yields and enantioselectivities. Furthermore, a stereodivergent synthesis of natural product NP25302 is achieved, and a reasonable reaction mechanism is proposed to illustrate the observed stereoselectivity based on the results of control experiments, nonlinear effect investigation, and HRMS detection.

Subject terms: Asymmetric catalysis, Synthetic chemistry methodology

The combination of transition metal catalysis and organocatalysis can afford both good reactivity and selectivity. Here, the authors present an α − propargylation of N-unprotected amino acid esters with propargylic alcohol derivatives via dual nickel and chiral aldehyde catalysis.

Introduction

The development of catalytic systems is an important work for asymmetric catalysis1,2. One of the most active research fields is the development of combining catalytic systems from organocatalysts and transition metals3–8. For example, chiral organocatalysts such as quaternary ammonium salts9,10, amines11–17, and brønsted acids18–22 have already been proven excellent catalyst partners for transition metals including palladium, rhodium, iridium, ruthenium, nickel, copper, etc. With the utilization of these combined catalysts, numerous challenging asymmetric organic transformations were achieved3–8. As an emerging asymmetric catalytic strategy, chiral aldehyde catalysis has been proven the most preferred one for the direct asymmetric α−functionalization of N-unprotected aminomethyl compounds23–27. However, most of the reported examples focused on the usage of chiral aldehydes as pure organocatalysts28–35, and the chiral aldehyde/transition metal combining catalytic systems were very rare (Fig. 1a)36–38. Especially, there was only one type of transition metal, the palladium, has been merged with chiral aldehyde catalysts36–38. So, the development of chiral aldehyde/transition metal-involved combining catalytic systems becomes an important way to achieve more challenging α−functionalization reactions of aminomethyl compounds.

Fig. 1. The reported chiral aldehyde catalytic systems and the asymmetric α−propargylation reaction of amino acid esters (LG = Leaving Group).

a The reported chiral aldehyde-involved catalytic systems. b The reported catalytic asymmetric α−propargylation of amino acid esters. c The chiral aldehyde/nickel catalyzed α−propargylation of N-unprotected amino acid derivatives (this work).

As a continuous work on our discovery of the chiral aldehyde/palladium combined catalysis36–38, we tried to employ another type of transition metal as a catalyst partner with chiral aldehydes. Palladium is a soft metal that has a large atomic radius and strong electronegative property, while nickel has different chemical properties (harder, smaller atomic radius, and less electronegative)39–42. Due to these unique properties, nickel catalysis has been widely used in organic reactions such as cross-coupling43,44, C-H activation45,46, reductive coupling47,48, etc. Among those reactions, the nickel-catalyzed asymmetric propargylation is an important strategy for the construction of optically active alkyne compounds49–58. Especially, the chiral Ni/Cu dual catalyzed asymmetric α−propargylation of aldimine esters reported by Guo et al provided a good solution for the preparation of chiral propargyl-functionalized amino acids59,60, a type of useful compound that has been seldom studied by synthetic chemists (Fig. 1b)61–65. With consideration of the unique properties of chiral aldehyde catalysis in activating amino acid derivatives, the combined chiral aldehyde/nickel catalytic system is fully anticipated for achieving this important transformation without additional steps of protection and deprotection.

In this work, we rational design a chiral aldehyde/nickel combining catalytic system, which can efficiently promote the direct asymmetric α−propargylation reaction of N-unprotected amino acid esters with propargyl alcohol derivatives. Various propargyl-functionalized α,α−disubstituted α−amino acid esters are generated in good-to-excellent yields and enantioselectivities. With the utilization of control experiments, nonlinear effect investigation and HRMS detection, a reasonable mechanism is proposed. Furthermore, this method is used for the stereodivergent synthesis of natural product NP25302 (Fig. 1c).

Results

Optimization of reaction conditions

Our work initiated with the evaluation of the reaction between tert-butyl alaninate 1a and benzoyl-protected 3-phenyl propargyl alcohol ester 2a, in the promotion of a combined catalytic system of chiral aldehyde 3a and Ni(COD)2. Lewis acid ZnCl2 and base 1,1,3,3-tetramethylguanidine (TMG) were added to accelerate the successive processes of Schiff base formation and deprotonation. As expected, the desired product 4a was generated with moderate yield and excellent enantioselectivity (Table 1, entry 1). Then, a series of reaction condition optimizations were carried out. Leaving group screening indicated that OAc was the optimal one that could give product 4a in 49% yield and with 94% ee (Table 1, entry 2). Base screening showed that TMG was the best choice (Supplementary Table 1). After we tuned the equivalents of the base from 1.0 to 1.6, the yield of 4a was efficiently improved to 71% (Table 1, entry 6; Supplementary Table 2). Subsequently, various diphosphine ligands were examined (Supplementary Table 3). Among them, chiral ligand L4 gave the best yield, albeit the enantioselectivity of 4a decreased slightly (Table 1, entry 9). With the utilization of TMG as base and L4 as ligand, chiral aldehydes 3b-3k and achiral aldehyde 3l-3m were individually employed as cocatalysts to replace chiral aldehyde 3a. We found that the combination of chiral aldehyde 3i and ligand L4 gave the best experimental results (Table 1, entry 17). The reactant concentration affected the yield of 4a slightly. After we increased the concentration of reactant 1a from 0.2 M to 0.4 M, the yield of 4a was further improved to 92% (Table 1, entry 22). Finally, the matching relationship between the chiral aldehyde and chiral ligand was investigated. Results show that the combination of ent-3i and L4 gave product 4a merely in 25% yield and 62% ee (Table 1, entry 23). So, the reaction conditions in entry 22 were chosen as the optimal ones for the next substrate scopes investigation. Under these optimal reaction conditions, we replaced the metal Ni(COD)2 with palladium Pd(PPh3)4 or [Pd(C3H5)Cl]2, no desired reaction occurred (Table 1, entry 24). These results indicated that this chiral aldehyde/nickel combining catalytic system has unique properties in achieving this type of organic transformation.

Table 1.

Reaction condition optimization

| |||||

| Entry | 3 | Ligand | LG | Yield (%)a | ee (%)b |

| 1 | 3a | L1 | OBz | 46 | 95 |

| 2 | 3a | L1 | OAc | 49 | 94 |

| 3 | 3a | L1 | OBoc | 34 | 90 |

| 4 | 3a | L1 | OCO2Me | 18 | 74 |

| 5 | 3a | L1 | OPO(OEt)2 | 14 | 76 |

| 6c | 3a | L1 | OAc | 71 | 93 |

| 7c | 3a | L2 | OAc | 6 | 22 |

| 8c | 3a | L3 | OAc | 10 | 87 |

| 9c | 3a | L4 | OAc | 80 | 91 |

| 10c | 3b | L4 | OAc | 64 | 97 |

| 11c | 3c | L4 | OAc | 11 | 94 |

| 12c | 3d | L4 | OAc | 70 | 94 |

| 13c | 3e | L4 | OAc | 78 | 90 |

| 14c | 3 f | L4 | OAc | 63 | 93 |

| 15c | 3 g | L4 | OAc | 14 | 94 |

| 16c | 3 h | L4 | OAc | 83 | 96 |

| 17c | 3i | L4 | OAc | 87 | 96 |

| 18c | 3j | L4 | OAc | 9 | 40 |

| 19c | 3k | L4 | OAc | 0 | – |

| 20c | 3 l | L4 | OAc | 33 | 82 |

| 21c | 3 m | L4 | OAc | 0 | – |

| 22 cd | 3i | L4 | OAc | 92 | 96 |

| 23 cd | ent-3ie | L4 | OAc | 25 | 62 |

| 24cdf | 3a | L1 | OAc | trace | – |

aIsolated yield.

bDetermined by chiral HPLC.

cWith 160 mol% TMG.

dWith 0.5 mL PhCH3.

eent-3i = the enantiomer of chiral aldehyde 3i.

fNi(COD)2 was replaced by Pd(PPh3)4 or [Pd(C3H5)Cl]2.

Substrate scope of propargylic alcohol derivatives

With the optimal reaction conditions in hand, we then investigated the substrate scopes. Firstly, various propargylic alcohol derivatives were tested. 3-Phenylprop-2-yn-1-yl acetates were good reaction partners for amino acid ester 1a, and the yields varied with the change of substituent position. Moderate yields were observed when compounds 2 bearing an ortho-substituted phenyl were involved in this reaction (Fig. 2, 4b-d). These moderate yields were possibly caused by the steric effect of ortho-substituents. Once the substituent was installed at the meta- or para-position of the phenyl, the desired products were obtained in good-to-excellent yields (Fig. 2, 4e-4m). Similar yields were observed in the reactions of 1a with corresponding propargylic alcohol derivatives bearing 3,4-disubstituted phenyl units (Fig. 2, 4n-4p). Notably, all of these 3-phenylprop-2-yn-1-yl acetates gave products with excellent enantioselectivities (92–98% ee). Other aryl-substituted propargylic alcohol acetates, including 2-naphthyl, 1-naphthyl, 9H-fluoren-3-yl, and 3-thienyl, were then tested. Except for that the 1-naphthyl substituted propargylic alcohol acetate gave product 4r in moderate yield (58%), all others reacted efficiently with 1a and gave desired products in excellent yields and enantioselectivities (Fig. 2, 4q-4t). Saturated aliphatic alkyl-substituted propargylic alcohol acetates also exhibited high reactivity with amino acid ester 1a, giving products 4s-4v in excellent yields and enantioselectivities. Two 3-phenylprop-2-yn-1-yl acetates bearing chiral side chains were tested; products 4w and 4x were obtained with moderate yields and excellent stereoselectivities (>20:1 dr). We found the secondary propargylic alcohol ester could not efficiently react with 1a under the optimal reaction conditions (Fig. 2, 4aa).

Fig. 2. The substrate scope of propargylic alcohol derivatives.

a With 20 mol% 3i and at 60 °C. b Ee value was obtained from its N-Bz-protected derivative.

Substrate scope of amino acid esters

Next, the substrate scope of amino acid esters was investigated. Phenyl glycine esters could participate in this reaction efficiently, however, to obtain high yields, it was necessary to increase the chiral aldehyde catalyst loading and rise the reaction temperature (Fig. 3, 5a-5d). Phenylalanine and homophenylalanine-derived esters also reacted efficiently with 2b, leading to products 5e-5i in good yields and excellent enantioselectivities. Representative amino acid esters bearing aliphatic alkyl, allyl, sulfur and ester-containing alkyls were used as donors, and all of them gave desired products in good-to-excellent yields and enantioselectivities (Fig. 3, 5j-5n).

Fig. 3. The substrate scope of amino acid esters.

a With 20 mol% 3i and at 60 °C. b With 20 mol% 3a and at 60 °C. c With 20 mol% 3i, 12 mol% L1, and at 60 °C. d With 12 mol% L1.

Stereodivergent synthesis of NP25302

NP25302 is a natural pyrrolizidine alkaloid that shows excellent biological activity in inhibiting the adhesion of HL-60 cells to CHO-ICAM-1 cells (IC50 = 27.2 μg/mL)66. However, studies on the total synthesis of this compound were very limited. In 2006, Snider and co-workers described a total synthesis of (R, R)- and (S, S)-NP2530267. Subsequently, Robertson and co-workers achieved a total synthesis of this compound in a racemic manner68. There are two chiral centers in this molecule, but the attempt to achieve all of the four stereoisomers has never been touched. With chiral aldehyde 3i and ligand L4, the methyl alaninate 1b reacted with but-2-yn-1-yl acetate 2c smoothly giving (S)-6 in 56% yield and 90% ee. Corresponding (R)-6 was obtained under the promotion of chiral aldehyde ent-3i and ligand ent-L4 (enantiomer of L4). Treatment of compounds 6 with AgOTf produced dihydropyrroles 7 in moderate yields. Then, the imine groups of 7 were reduced by NaBH3CN. The (S, R)-8 and (S, S)-8 were generated from (S)-7, and the (R, R)-8 and (R, S)-8 were generated from (R)-7. All of the diastereoisomers were separated by flash column chromatography. After reacting with BrCN under basic conditions, four stereoisomers of 9 were obtained in good yields. (S, S)- and (R, R)-9 were reported as the key chiral building blocks leading to (S, S)- and (R, R)-NP2530267. So, (S, R)- and (R, S)-9 were used for the synthesis of the other two isomers. (S, R)- and (R, S)-11 were produced in good yields by a Claisen condensation with tert-butyl acetate and an intramolecular cyclization reaction. Protecting the amino group of compounds 11, and decarboxylation of their tert-butyl ester groups, (S, R)- and (R, S)-NP25302 were respectively generated in good yields and enantioselectivities. Thus, all four stereoisomers of NP25302 could be synthesized from the readily available starting materials 1b and 2c within 8 steps (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Synthetic application.

The stereodivergent synthesis of NP25302 from amino acid ester 1b and propargylic alcohol ester 2c.

Discussion

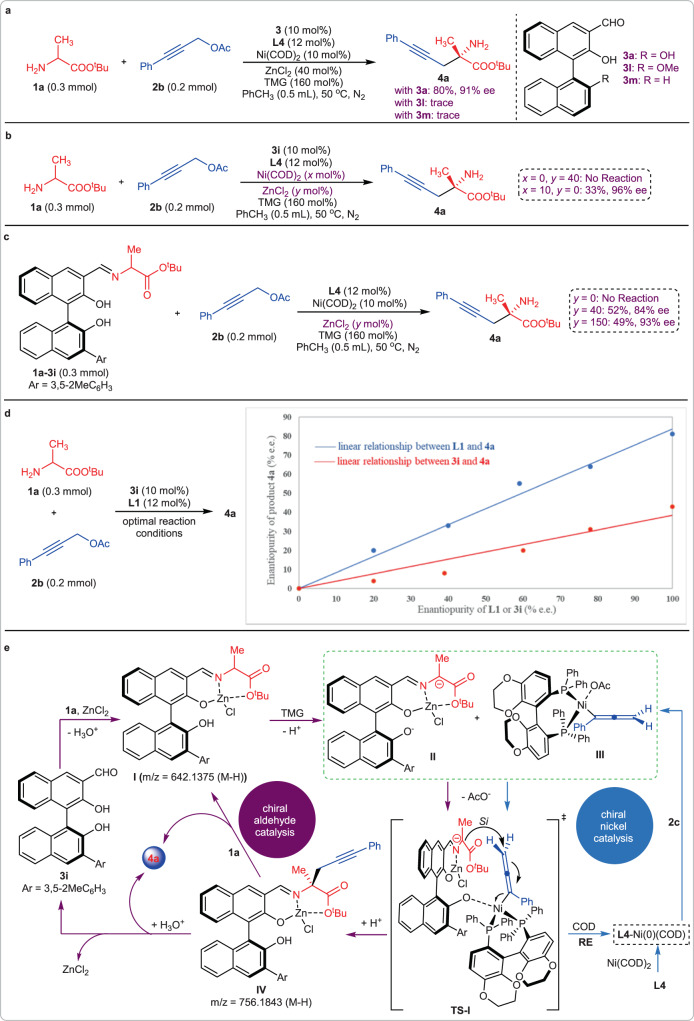

The possible reaction mechanism was then investigated. Firstly, two modified chiral aldehyde catalysts 3n and 3o were used to promote the model reaction, and only trace amounts of 4a were observed. Comparing these results with that obtained from chiral aldehyde catalyst 3a shows that the 2’-hydroxyl is vital for this reaction (Fig. 5a). Like the transition state we previously disclosed8, the formation of a coordination bond between the 2’-hydroxyl and an active nickel species is possible. The role of the transition metal and Lewis acid were then studied. In the absence of nickel, this reaction could not take place, indicating that the active electrophile intermediate must be generated by nickel catalysis. The yield of 4a decreased greatly in the absence of ZnCl2, showing that the reaction process could be accelerated by this Lewis acid. The reaction of Schiff base 1a-3i with 2b was carried out to further investigate the role of Lewis acid. Results indicated that the yield and ee varied with the equivalents of ZnCl2. No reaction occurred in the absence of ZnCl2. When 0.4 equivalents of Lewis acid were employed, product 4a was generated in 52% yield and 84% ee. After the equivalents of Lewis acid were increased to 1.5, the ee of 4a was enhanced to 93% (Fig. 5c). These results indicated that the Lewis acid ZnCl2 was involved in the transition state and acted a vital role in the enantioselective control. To verify this, we detected this reaction by HRMS. Two Schiff base-Zn complexes, I and IV, were directly observed and furtherly verified by comparing their isotopic distributions with theoretical data (Supplementary Fig. 3). All of these results provided good evidence for the conclusion that the Lewis acid ZnCl2 could: (1) speed the Schiff base formation process, (2) furtherly enhance the α−carbon acidity of the Schiff base and then accelerate the subsequent deprotonation process, and (3) strengthen the stereoselective-control ability of the transition state. The nonlinear effect of the enantiopurity between product 4a and two chiral sources, the chiral aldehyde 3i and chiral ligand L1, was then studied. Results indicated that both these two chiral sources exhibited linear relationships with 4a, so, it is reasonable to deduce that only one molecule of chiral aldehyde and one molecule of chiral ligand were involved in the transition state (Fig. 5d). Combining the above results with the absolute S conformation of product 4a, a possible reaction mechanism was proposed in Fig. 5e. Chiral aldehyde 3i reacted with amino acid ester 1a in the promotion of Lewis acid ZnCl2, leading to the stable Schiff base-Zn complex I. Then this complex was deprotonated by TMG to form an active nucleophile II. At the same time, an active chiral nickel species (III) was formed from propargylic alcohol ester 2c and L4-Ni(0)(COD) via oxidative addition. With a ligand exchange, TS-I was formed from active intermediates II and III. The α−carbon anion of II provided its Si face to attack the active allenylic nickel species, leading to Schiff base-Zn complex IV via reductive elimination (RE) and protonation processes. Product 4a was then generated by hydrolysis or amine exchange.

Fig. 5. Reaction mechanism investigation.

a Control experiments with modified chiral aldehyde catalysts. b Control experiments to investigate the role of nickel and ZnCl2. c Control experiments with Schiff base as reactants. d The nonlinear effect investigation between the ee value of product 4a and chiral sources 3i or L1. e The possible catalytic cycles. (x = the equivalents of Ni(COD)2, y = the equivalents of ZnCl2).

In conclusion, we disclosed a highly efficient chiral aldehyde-nickel dual catalytic system and its application in the asymmetric α−propargylation reaction of N-unprotected amino acid esters with propargylic alcohol derivatives. Forty-two structural diversity α,α−disubstituted α−amino acid esters were obtained in yields of 31–95% and ee values of 79–98%. Products (R)- and (S)-6 were used for the total synthesis of the four stereoisomers of natural product NP25302. According to the results given by control experiments and nonlinear effect investigation, and the key intermediates detected by HRMS, a reasonable reaction mechanism is proposed to illustrate the enantioselective control phenomenon.

Methods

Method for the catalytic asymmetric α−propargylation of amino acids

In a nitrogen-filled glove box, an oven-dried 10 mL screw-cap reaction tube equipped with a stir bar was charged with Ni(COD)2 (5.5 mg, 0.02 mmol), (R)-synphos (15.3 mg, 0.024 mmol) and stirred in toluene (0.5 mL) at room temperature for about 5 minutes. Then, tert-butyl amino acid ester 1 (0.3 mmol), propargylic acetate ester 2 (0.2 mmol), chiral aldehyde 3i (8.2 mg, 0.02 mmol), ZnCl2 (10.9 mg, 0.08 mmol) and TMG (36.8 mg, 0.32 mmol) were added. The mixture was continuously stirred at 50 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere. After the reaction was completed, the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation, and the residue was purified by flash chromatography separation on a silica gel column (eluent: petroleum ether/ethyl acetate/triethylamine = 250/100/2). The details of the full experiments and compound characterizations were provided in the Supplementary Information.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for financial support from NSFC (22071199, 22201235), the Innovation Research 2035 Pilot Plan of Southwest University (SWU-XDZD22011), and the Chongqing Science Technology Commission (cstccxljrc201701, cstc2018jcyjAX0548).

Author contributions

W.W. and G.Q.X. conceived this project. Z.F. and L.C.X. carried out the experiments. W.Z.L. and C.T. performed the HRMS analysis. G.Q.X. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Data availability

The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information file.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Wei Wen, Email: wenwei1989@swu.edu.cn.

Qi-Xiang Guo, Email: qxguo@swu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-022-35062-2.

References

- 1.Trost BM. Asymmetric catalysis: An enabling science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:5348–5355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306715101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noyori R. Asymmetric catalysis: science and opportunities (Nobel lecture) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:2008–2022. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020617)41:12<2008::AID-ANIE2008>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han Z-Y, Gong L-Z. Asymmetric organo/palladium combined catalysis. Prog. Chem. 2018;30:505–512. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen D-F, Gong L-Z. Organo/transition-metal combined catalysis rejuvenates both in asymmetric synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144:2415–2437. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c11408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen D-F, Han Z-Y, Zhou X-L, Gong L-Z. Asymmetric organocatalysis combined with metal catalysis: concept, proof of concept, and beyond. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:2365–2377. doi: 10.1021/ar500101a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez-Ibanez M, Macia B, Alonso D-A, Pastor I-M. Palladium and organocatalysis: an excellent recipe for asymmetric synthesis. Molecules. 2013;18:10108–10121. doi: 10.3390/molecules180910108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhong C, Shi X-D. When organocatalysis meets transition-metal catalysis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010;2010:2999–3025. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201000004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shao Z-H, Zhang H-B. Combining transition metal catalysis and organocatalysis: a broad new concept for catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:2745–2755. doi: 10.1039/b901258n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen G-S, et al. Palladium-catalyzed allylic alkylation of tert-butyl(diphenylmethylene)-glycinate with simple allyl esters under chiral phase transfer conditions. Tetrahedron-Asymmetry. 2001;12:1567–1571. doi: 10.1016/S0957-4166(01)00276-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakoji M, Kanayama T, Okino T, Takemoto Y. Chiral phosphine-free pd-mediated asymmetric allylation of prochiral enolate with a chiral phase-transfer catalyst. Org. Lett. 2001;3:3329–3331. doi: 10.1021/ol016567h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibrahem I, Córdova A. Direct catalytic intermolecular α-allylic alkylation of aldehydes by combination of transition-metal and organocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:1952–1956. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bihelovic F, Matovic R, Vulovic B, Saicic RN. Organocatalyzed cyclizations of π-allylpalladium complexes: a new method for the construction of five- and six-membered rings. Org. Lett. 2007;9:5063–5066. doi: 10.1021/ol7023554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nielsen CRT, Linfoot JD, Willianms AF, Spivey AC. Recent progress in asymmetric synergistic catalysis−the judicious combination of selected chiral aminocatalysts with achiral metal catalysts. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022;20:2764–2778. doi: 10.1039/D2OB00025C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cozzi PG, Gualandi A, Potenti S, Calogero F, Rodeghiero G. Asymmetric reactions enabled by cooperative enantioselective amino-and lewis acid catalysis. Top. Curr. Chem. 2020;378:1. doi: 10.1007/s41061-019-0261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gualandi A, Mengozzi L, Wilson CM, Cozzi PG. Synergy, compatibility, and innovation: merging lewis acids with stereoselective enamine catalysis. Chem. Asian J. 2014;9:984–995. doi: 10.1002/asia.201301549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Afewerki S, Cordova A. Enamine/transition metal combined catalysis: catalytic transformations involving organometallic electrophilic intermediates. Top. Curr. Chem. 2019;377:38. doi: 10.1007/s41061-019-0267-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Afewerki S, Cordova A. Combinations of aminocatalysts and metal catalysts: a powerful cooperative approach in selective organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:13512–13570. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komanduri V, Krische MJ. Enantioselective reductive coupling of 1,3-enynes to heterocyclic aromatic aldehydes and ketones via rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation: mechanistic insight into the role of brønsted acid additives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:16448–16449. doi: 10.1021/ja0673027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mukherjee S, List B. Chiral counteranions in asymmetric transition-Metal catalysis: Highly enantioselective Pd/Brønsted acid-catalyzed direct α-allylation of aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:11336–11337. doi: 10.1021/ja074678r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rueping M, Koenigs RM, Atodireser I. Unifying metal and bronsted acid catalysis-concepts, mechanisms, and classifications. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:9350–9365. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang P-S, Chen D-F, Gong L-Z. Recent progress in asymmetric relay catalysis of metal complex with chiral phosphoric acid. Top. Curr. Chem. 2020;378:9. doi: 10.1007/s41061-019-0263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parmar D, Sugiono E, Raja S, Rueping M. Complete field guide to asymmetric BINOL-phosphate derived bronsted acid and metal catalysis: history and classification by mode of activation; bronsted acidity, hydrogen bonding, ion pairing, and metal phosphates. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:9047–9153. doi: 10.1021/cr5001496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Q, Gu Q, You S-L. Enantioselective carbonyl catalysis enabled by chiral aldehydes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:6818–6825. doi: 10.1002/anie.201808700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J-F, Liu Y-E, Gong X, Shi L-M, Zhao B-G. Biomimetic chiral pyridoxal and pyridoxamine catalysts. Chin. J. Chem. 2019;37:103–112. doi: 10.1002/cjoc.201990022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin K-J, Shi A, Shi C-H, Lin J-B, Lin H-G. Catalytic asymmetric amino acid and its derivatives by chiral aldehyde catalysis. Front. Chem. 2021;9:687817. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2021.687817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan Z-Q, Liao J, Jiang H, Cao P, Li Y. Aldehyde catalysis−from simple aldehydes to artificial enzymes. RSC Adv. 2020;10:35433–35448. doi: 10.1039/D0RA06651F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang R, Shao Z. Diastereodivergent chiral aldehyde catalysis for asymmetric 1,6-conjugated addition and mannich reactions. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2021;41:428–430. doi: 10.6023/cjoc202100005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu B, et al. Catalytic asymmetric direct α-alkylation of amino esters by aldehydes via imine activation. Chem. Sci. 2014;5:1988–1991. doi: 10.1039/c3sc53314j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen J, et al. Carbonyl catalysis enables a biomimetic asymmetric Mannich reaction. Science. 2018;360:1438–1442. doi: 10.1126/science.aat4210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wen W, et al. Chiral aldehyde catalysis for the catalytic asymmetric activation of glycine esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:9774–9780. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b06676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wen W, et al. Diastereodivergent chiral aldehyde catalysis for asymmetric 1,6-conjugated addition and Mannich reactions. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5372. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19245-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang W-Z, Shen H-R, Liao J, Wen W, Guo Q-X. A chiral aldehyde-induced tandem conjugated addition-lactamization reaction for constructing fully substituted pyroglutamic acids. Org. Chem. Front. 2022;9:1422–1426. doi: 10.1039/D1QO01923F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma J-G, et al. Enantioselective synthesis of pyroglutamic acid esters from glycinate via carbonyl catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:10588–10592. doi: 10.1002/anie.202017306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma, J.-G. et al. Asymmetric alpha-allylation of glycinate with switched chemoselectivity enabled by customized bifunctional pyridoxal catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 10.1002/anie.202200850 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Cheng A-L, et al. Efficient asymmetric biomimetic aldol reaction of glycinates and trifluoromethyl ketones by carbonyl catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:20166–20172. doi: 10.1002/anie.202104031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen L, Luo M-J, Zhu F, Wen W, Guo Q-X. Combining chiral aldehyde catalysis and transition-metal catalysis for enantioselective α-allylic alkylation of amino acid esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:5159–5164. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b01910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu F, et al. Direct catalytic asymmetric α-allylic alkylation of aza-aryl methylamines by chiral-aldehyde-involved ternary catalysis system. Org. Lett. 2021;23:1463–1467. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.1c00143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu J-H, et al. Catalytic asymmetric Tsuji-Trost α-benzylation reaction of N-unprotected amino acids and benzyl alcohol derivatives. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:2509. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30277-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tasker SZ, Standley EA, Jamison TF. Recent advances in homogeneous nickel catalysis. Nature. 2014;509:299–309. doi: 10.1038/nature13274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keim W. Nickel: An Element with Wide Application in Industrial Homogeneous. Catal. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1990;29:235–244. doi: 10.1002/anie.199002351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clevenger AL, Stolley RM, Aderibigbe J, Louie J. Trends in the usage of bidentate phosphines as ligands in nickel catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2020;120:6124–6196. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruan H, Dong Z-C, Chen C-X, Wu S, Sun J-C. Recent progress on the nickel/photoredox dual catalysis. J. Org. Chem. 2017;37:2544–2554. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wenger OS. Photoactive nickel complexes in cross-coupling catalysis. Chem. Eur. J. 2021;27:2270–2278. doi: 10.1002/chem.202003974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cavalcanti LN, Molander GA. Photoredox catalysis in Nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling. Top. Curr. Chem. 2016;374:39. doi: 10.1007/s41061-016-0037-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pototschnig G, Maulide N, Schnurch M. Direct functionalization of C-H bonds by iron, nickel, and cobalt catalysis. Chem. Eur. J. 2017;23:9206–9232. doi: 10.1002/chem.201605657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mantry L, Maayuri R, Kumar V, Gandeepan PB. Photoredox catalysis in nickel-catalyzed C-H functionalization. J. Org. Chem. 2021;17:2209–2259. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.17.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richmond E, Moran J. Recent advances in Nickel catalysis enabled by stoichiometric metallic reducing agents. Synth.-Stuttg. 2018;50:499–513. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1591853. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eliezer O, Jonathan S, Chang Y-H, Michael JK. Enantioselective metal-catalyzed reductive coupling of alkynes with carbonyl compounds and imines: convergent construction of allylic alcohols and amines. ACS Catal. 2022;12:8164–8174. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.2c02444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ding C-H, Hou X-L. Catalytic asymmetric propargylation. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1914–1937. doi: 10.1021/cr100284m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsuji H, Kawatsura MA. Transition-metal-catalyzed propargylic substitution of propargylic alcohol derivatives bearing an internal alkyne group. J. Org. Chem. 2020;9:1924–1941. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nishibayashi Y. Transition-metal-catalyzed enantioselective propargylic substitution reactions of propargylic alcohol derivatives with nucleophiles. Synthesis. 2012;44:489–503. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1290158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miyazaki Y, Zhou B, Tsuji H, Kawatsura M. Nickel-catalyzed asymmetric friedel-crafts propargylation of 3-substituted indoles with propargylic carbonates bearing an internal alkyne group. Org. Lett. 2020;22:2049–2053. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c00465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu XH, Peng L-Z, Chang X-H, Guo C. Ni/chiral sodium carboxylate dual catalyzed asymmetric O-propargylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;143:21048–21055. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c11044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu F-D, Jiang X, Lu L-Q, Xiao W-J. Application of propargylic radicals in organic synthesis. Acta Chim. Sin. 2019;77:803–813. doi: 10.6023/A19060201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watanabe K, et al. Nickel-catalyzed asymmetric propargylic amination of propargylic carbonates bearing an internal alkyne group. Org. Lett. 2018;20:5448–5451. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b02325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith S-W, Fu G-C. Nickel-catalyzed asymmetric cross-couplings of racemic propargylic halides with arylzinc reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12645–12647. doi: 10.1021/ja805165y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schley ND, Fu GC. Nickel-catalyzed negishi arylations of propargylic bromides: a mechanistic investigation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:16588–16593. doi: 10.1021/ja508718m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oelke AJ, Sun JW, Fu G-C. Nickel-catalyzed enantioselective cross-couplings of racemic secondary electrophiles that bear an oxygen leaving group. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:2966–2969. doi: 10.1021/ja300031w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peng L-Z, He Z-Z, Xu X-H, Guo C. Cooperative Ni/Cu-catalyzed asymmetric propargylic alkylation of aldimine esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:14270–14274. doi: 10.1002/anie.202005019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.He Z-Z, Peng L-Z, Guo C. Catalytic stereodivergent total synthesis of amathaspiramide D. Nat. Synth. 2022;1:393–400. doi: 10.1038/s44160-022-00063-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xia J-T, Hu X-P. Copper-catalyzed decarboxylative propargylic alkylation of enol carbonates: stereoselective synthesis of quaternary α−amino acids. ACS Catal. 2021;11:11843–11848. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.1c03421. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lu W-Y, et al. Copper-catalyzed decarboxylative [3 + 2] annulation of ethynylethylene carbonates with azlactones: access to γ-butyrolactones bearing two vicinal quaternary carbon centers. J. Org. Chem. 2021;86:1779–1788. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.0c02621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhu Q-Q, et al. Diastereo- and enantioselective synthesis of quaternary α-amino acid precursors by copper-catalyzed propargylation. Org. Lett. 2019;21:9985–9989. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang J, Ni T, Yang W-L, Deng W-P. Catalytic asymmetric [3 + 2] annulation via indolyl copper–allenylidene intermediates: diastereo- and enantioselective assembly of pyrrolo[1,2-a] indoles. Org. Lett. 2020;22:4547–4552. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Noda H, Amemiya F, Weidner K, Kumagai N, Shibasaki M. Catalytic asymmetric synthesis of CF3-substituted tertiary propargylic alcohols via direct aldol reaction of α-N3 amide. Chem. Sci. 2017;8:3260–3269. doi: 10.1039/C7SC00330G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang Q, Schrader KK, ElSohly HN, Takamatsu SJ. New cell-cell adhesion inhibitors from streptomyces sp. UMA-044. Antibiot. 2003;56:673–681. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.56.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Duvall JR, Wu F-H, Snider BB. Structure reassignment and synthesis of jenamidines A1/A2, synthesis of (+)-NP25302, and formal synthesis of SB-311009 analogues. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:8579–8590. doi: 10.1021/jo061650+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stevens K, Tyrrell AJ, Skerratt S, Robertson J. Synthesis of NP25302. Org. Lett. 2011;13:5964–5967. doi: 10.1021/ol202381m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information file.