Abstract

This report has analyzed the potential role of Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV) UL24 and UL43 products in modulating the subcellular location of a host restriction factor, SAMHD1, in cells of human fibroblast origin. Recent studies have reported that the regulation of SAMHD1 is mediated by the HCMV UL97 product inside the nucleus, and by the CDK pathway when it is located in the cytoplasm of the infected cells but the viral gene products that may involve in cytosolic relocalization remain unknown yet. In the present report, we demonstrate that the HCMV UL24 product interacts with the SAMHD1 protein during infection based on mass spectrometry (MS) data and immunoprecipitation assay. The expression or depletion of the viral UL24 gene product did not affect the subcellular localization of SAMHD1 but when it coexpressed with the viral UL43 gene product, another member of the HCMV US22 family, induced the SAMHD1 cytosolic relocalization. Interestingly, the double deletion of viral UL24 and UL43 gene products impaired the cytosolic translocation and the SAMHD1 was accumulated in the nucleus of the infected cells, especially at the late stage post-infection. Our results provide evidence that the viral UL24 and UL43 gene products play a role in the SAMHD1 subcellular localization during HCMV infection.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13337-022-00799-3.

Keywords: Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV), HCMV UL24, HCMV UL43, SAMHD1, HCMV-Host Interaction

Introduction

The SAMHD1 is 626 amino acids long and is made up of two main domains, SAM and HD. SAM domain acts through protein–protein and protein–nucleic acid interactions, and it is a docking site for kinases, signal transduction, and regulation of transcription [2, 11]. On the other hand, the HD domain is characterized by dNTP triphosphatase activity [1, 11]. Recent studies confirmed that SAMHD1 also has nuclease activity [4]. SAMHD1 is activated by oligomerization and tetramerization [40], and is inactivated by phosphorylation [39], subcellular localization [32], mutations, and methylation [9, 38].

Early studies of the SAMHD1 protein were related to Aicardi-Goutie'res syndrome (AGS), a rare immunological condition linked to mutations in the SAMHD1 gene and type I IFN inductions [5, 24, 31]. In cancer cells, degradation of SAMHD1 occurs during the S phase of the cell cycle [18]. Mutations in the SAMHD1 gene or methylation of the SAMHD1 promoter can affect the transcription of mRNA in cancer cells [9, 38]. SAMHD1 has also been reported to suppress innate immune responses to viral infections and inflammatory diseases [11].

Many studies reported SAMHD1 as a potent host restriction factor that inhibits the replication of a wide range of RNA and DNA viruses, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other retroviruses [15, 20–23, 25, 28], hepatitis B virus (HBV) [7, 33], vaccinia virus, and Herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) [3, 14]. SAMHD1 is studied more in retroviruses, especially HIV infection. It can inhibit HIV and other retroviruses in cycling cells through its phosphohydrolase activity [12, 29]. This phosphohydrolase activity converts deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) to inorganic phosphate (triphosphate) and deoxynucleoside, decreasing the dNTP pools available for reverse transcription and viral DNA synthesis [10, 25, 32]. SAMHD1 has also been reported to inhibit the hepatitis B virus (HBV), a partially DNA virus, by limiting the viral reverse transcription step [7, 33]. SAMHD1 can restrict other DNA viruses, such as Herpesviruses, by depleting the dNTP pools required for DNA synthesis and viral replication [4] or limiting the NF-kB activity required for viral gene expression [17].

Despite the potent restriction activity of SAMHD1, viruses have evolved different strategies and mechanisms to limit the activity of SAMHD1 protein by degradation, phosphorylation, or subcellular localization. For example, a study reported that HIV-2 could inhibit SAMHD1 activity by a lentiviral protein, known as the Vpx protein, targeting SAMHD1 degradation and increasing the pool of dNTP required for efficient reverse transcription and viral replication [25]. Another report has identified that HIV-1 uses tetraspanin CD81 as a rheostat to regulate different stages of the infection via SAMHD1 nuclear export induced by a direct association of CD81 with the deoxynucleoside triphosphate phosphohydrolase of SAMHD1 protein in HIV-1-infected cells. This interaction enhances the proteasome-dependent degradation of SAMHD1, increases dNTPs, and enhances HIV-1 reverse transcription and replication [32]. HIV has also been shown to regulate SAMHD1 by forming the SAMHD1–CDK1 complex, more likely in the cytoplasm, which mediates SAMHD1 phosphorylation at threonine 592 and inactivates its restriction function [10, 39].

Beta-herpesviruses are also among the common viruses that can overcome the antiviral activity of SAMHD1 in different pathways. Recent studies have identified that the Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV), a beta herpesvirus, can restrict the activity of SAMHD1 via direct binding and phosphorylation with the viral protein kinase UL97 inside the nucleus of infected cells. They also described that SAMHD1 could be phosphorylated at residue T592 after infection by cellular cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK2) pathway inside the cytoplasm of infected fibroblast cells in association with viral particles and dense bodies [26, 42], but the viral factors that induce the subcellular localization of SAMHD1 in HCMV-infected cells remain unknown yet.

Therefore, in our report, we examed to identify which viral genes may involve in SAMHD1 subcellular localization. To check that, we firstly infected the MRC5 cells (cells of fibroblast origin) with HCMV, and the protein bands were analyzed by the silver staining method and sent for mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. Based on MS data and confirmed co-immunoprecipitation assays, we identified that UL24 could interact with the SAMHD1 protein. Thus this suggests that UL24, a cytosolic tegument protein, may involve in the induction of SAMHD1 relocalization in infected cells through direct binding. Therefore, we overexpressed the UL24gene in MRC5 cells to check if it can trigger the SAMHD1 nuclear export, but there was no obvious induction. Thus, we expected that UL24 may cooperate with other viral or host factors to regulate the location of SAMHD1. According to a previous report, the viral product UL24 can bind with UL43, another member of the HCMV US22 family, on the protein level [36], and we demonstrated that their coexpression has partially triggered SAMHD1 cytoplasmic translocation up on confocal microscopic examination. Besides, the double knockout of the viral UL24 and UL 43 gene products induced SAMHD1 nuclear retention in HCMV-infected cells.

These results suggest that HCMV, similar to other retroviral infections, evolves different pathways to restrict SAMHD1 antiviral activity via direct post-translational phosphorylation inside the nucleus by viral UL97 kinase, and subcellular localization by viral UL24–UL43 cooperation. This report at least provides some basis for the partial SAMHD1 cytosolic relocalization by HCMV genes in cells of fibroblast origin.

Materials and methods

Plasmids

The overexpressed plasmids were constructed based on the empty plasmid pLKO.DCMV.TetO [26]. The pLKO-3 × Flag-sf-GFP plasmid overexpresses GFP, and the pLKO-3 × Flag-sf-UL43 plasmid overexpresses pUL43. Also, the pLKO-3 × Flag-sf-UL24 plasmid overexpresses pUL24, and the pLKO-HA-UL43 plasmid overexpresses pUL43. The primers needed to construct the above plasmids by enzyme digestion ligation or infusion method are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers for plasmids construction

| Plasmid name | Primer sequence (5'–3') |

|---|---|

| pLKO-3xFlag-sf-GFP |

F: ACGCGTCGACGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGG R: GGAATTCCTTGTACAGCTCGTCC |

| pLKO-3 × Flag-sf-UL24 |

F: TGATGATAAAGTCGACGAGGAGACCCGGGCGGG R: TCGAGGTCGAGAATTCTCAACGGTGCTGACGTC |

| pLKO-HA-UL43 |

F: GCGGCCGCGGATCCGAGAAAACGCCGGCGGAGAC R: CGGAATTCTCACCTTCGAGCAAAGAGCCCC |

| pLKO-GFP-UL24 |

F: GATGATAAAGTCGACGAGGAGACCCGGGCGGG R: CTAGATATCACGCGTCGACTCAACGGTGCTGACGTCC |

| pLKO-mcherry-UL24 |

F: GAGCTGTACAAGACCGGTGAGGAGACCCGGGCGGGACG R: CTAGATATCACGCGTCGACTCACCGGTGCTGACGTCC |

| pLKO-GFP-UL43 |

F:GCATGGACGAGCTGTACAAGGGATCCGAGAAAACGCCGGCGGAG R: CGGAATTCTCACCTTCGAGCAAAGAGCC |

| Plko-Mcherry |

F: ACGCGTCGACCATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAG R: CTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCC |

F forward; R reverse

For truncation, based on the secondary structure prediction, we split the UL24 protein sequences (362 aa) into the N and C terminus halves at amino acid 200 as follows: N terminus (1–200 aa), N terminus + C terminus 1 (NC1) (1–240 aa): N terminus + C terminus 2 (NC2) (1–322 aa), N terminus + C terminus 3 (NC3) (1-336aa), N terminus + C terminus 4 (NC4) (1–347 aa), N terminus + C terminus 5 (NC5) (1–356 aa) and whole ul24 (1–362 aa).

For the mutation, amino acid sequences were changed to alanine (ACG) amino acids. Primers were used for UL24 truncation and mutation (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Primers for UL24 truncation and mutation

| UL24 Plasmid | Sequence (5’–3’) |

|---|---|

| PLko-3*Flag-UL24 N-ter (1–200 aa) |

F:CTGACCGGTGAGGAGACCCGGGCGGGACGTTAT R:GGAATTCCTAGGTCAGGTAGCGCATGCA |

| PLko-3*Flag-UL24 NC1 (1–240 aa) |

F:CTGACCGGTGAGGAGACCCGGGCGGGACGTTAT R:GGAATTCCTAGTGAGGAAAGGGCGCGTTCTCGCC |

| PLko-3*Flag-UL24 NC2 (1–322 aa) |

F:CTGACCGGTGAGGAGACCCGGGCGGGACGTTAT R: GGAATTCCTACACCCGGATGTAGCGGTCGTCGCG |

| PLko-3*Flag-UL24 NC3 (1–336 aa) |

F:CTGACCGGTGAGGAGACCCGGGCGGGACGTTAT R:GGAATTCCTACAGGTTAAGTCCCAGACACATGAAG |

| PLko-3*Flag-UL24 NC4 (1–347 aa) |

F:CTGACCGGTGAGGAGACCCGGGCGGGACGTTAT R:GGAATTCCTACAGGTTAAGTCCCAGACACATGAAG |

| PLko-3*Flag-UL24 NC5 (1–356 aa) |

F:CTGACCGGTGAGGAGACCCGGGCGGGACGTTAT R:GGAATTCCTACAGGTTAAGTCCCAGACACATGAAG |

| PLko-3*Flag-UL24 mutant KRR |

F: CTGACCGGTGAGGAGACCCGGGCGGGACGTTAT R: GGAATTCTCAGGCGTGCTGGGCTCCGGCGGGGC AGTCGGGCACGCG |

| PLko-3*Flag-UL24 mutant G |

F: CTGACCGGTGAGGAGACCCGGGCGGGACGTTAT R:GGAATTCTCAACGGTGCTGACGGGCTTTGGGGCAG TCGGGCACGCG |

| PLko-3*Flag-UL24 mutant QH |

F: CTGACCGGTGAGGAGACCCGGGCGGGACGTTAT R:GGAATTCTCAACGGGCGGCACGTCCTTTGGGGCA GTCGGGCACGCG |

| PLko-3*Flag-UL24 mutant KGRQHR |

F: CTGACCGGTGAGGAGACCCGGGCGGGACGTTAT R:TGTCTCGAGGTCGAGAATTCTCAGGCGGCGGCGGC GGCGGCGGGGCAGTCGGGCACGCGATCGTA |

F forward, R reverse, aa amino acid

Antibodies and reagents

The antibodies used in this section were anti-Flag (Proteintech), anti-HA (Proteintech), anti-SAMHD1 (Rabbit Polyclonal Antibody, Proteintech), secondary antibody (Goat Anti-Rabbit (IgG), Proteintech) and anti-tubulin (Proteintech).

The reagents applied were a small plasmid extraction kit (Axygen), a gel recovery kit (Axygen), a purification kit of the PCR product (Axygen), and a small plasmid extraction kit (Tiangen), and DNA polymerase (PrimeStar).

Infusion ligase and restriction enzymes EcoRI and SalI were from Takara. DNA ligase, magnetic beads, and flag beads were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and magnetic beads and protein A beads were purchased from Invitrogen. Additionally, phosphate-buffered PBS (Hyclone), high glucose cell culture medium DMEM, and fetal bovine serum were purchased from Gibco. Other chemicals used are benzonase (70,664, EMD Millipore), phosphonoacetic acid (PAA) (284270-10G, Sigma-Aldrich), l-( +)-arabinose (5328-37-0, Urchem) and a protein inhibitor cocktail (PIC) (Roche).

BAC construction

A wild-type HCMV Bacterial Artificial chromosome (BAC) is used and changed based on requirements. The wild-type virus BAC is pBAC-AD/Cre tagged with GFP or Mcherry fluorescent material, which is changed from pBAC-AD/Cre that carries the complete viral genome of the wild-type HCMV experimental virus strain (HCMV AD169). pBAC-AD/Cre-GFP or Cre-Mcherry is generated by replacing the pBAC-AD/Cre virus gene US4-6 with the green or red fluorescent gene (GFP or Mcherry respectively), which is expressed under the control of the simian virus (SV40) early promoter.

For the construction of the recombinant mutant virus, the two-step Red Recombination System (Red Recombination System) is applied as aforementioned [35], which can perform point mutation, deletion, and fragment insertion modifications to the BAC carrying the viral genome, and recombination of the modified BAC carrying the Kanna gene (kanamycin). The BAC is electroporated to the competent E. coli GS1783. After induction with l-arabinose, the Kanna gene is removed to obtain the target recombinant BAC. Finally, the BAC is electroporated to the MRC5 cells to promote the virus replicates in the cells and generate the virus particles. Infected cells release the virus into the media.

All recombinant HCMV BAC clones in this study were derived from pBAC-AD/Cre-GFP using a Red BAC recombination protocol [16, 37, 41].

In the beginning, we deleted UL24 based on pBAC-AD/Cre-GFP ( known as pBAC-dd24), and then it was used again to delete the UL43 gene. At first, the fragment amplified with PCR IsceI-KanS was transferred to E. coli GS1783 containing wild-type pBAC-AD/Cre-GFP by electroporation. The electroporated bacteria were coated on the chloramphenicol/Kana double-antibody plate and passed homology. The recombinant fragment IsceI-KanS replaces the UL24 gene, and the second recombination is the same as above. Hence, pBAC-AD-dd24 was obtained. After PCR amplification of the IsceI-KanS fragment, the UL43 gene was replaced by the homologous recombination fragment IsceI-KanS. In the second step, l-arabinose-induced enzyme digestion was the same as above. Finally, the pBAC-AD-dd24/dd43 pair was obtained. The primers used in the recombinant BAC in this experiment are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Primers for BAC Recombination

| BAC name | Primer Sequence (5'–3') |

|---|---|

| ΔUL24 BAC(AD type) |

F: TCTGCTGAGGTGCGTTCGGCTCAGTTGCTTA CCTGCATACCTGTGACGCCACGAGTGACGTAGG GATAACAGGGTAATCGATTT R: TATGCCCCAAGCAGCGTCGTCGTCACTCGTG GCGTCACAGGTATGCAGGTAAGCAACTGAGCCA GTGTTACAACCAATTAACC |

| ΔUL43 BAC(AD type) |

F: GGCCGCGTGCCTGGGAACGCGCGCACGGCGC GGTCCCGTGACCGCGGACGCCGTCGGTACAGGATGACGACGATAAGTAGGG R: TGGTAACTGTGGTGGAGACGGTACCGACGGC GTCCGCGGTCACGGGACCGCGCCGTGCGCCAACC AATTAACCAATTCTGATTAG |

F forward, R reverse

Cells

HEK293T cells (SV40 large T-transformed HEK293 cells) were provided by Professor Jin Zhong at the Institut Pasteur of Shanghai, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Primary human embryonic lung fibroblasts (MRC5) were from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) available at https://www.atcc.org/products/all/CCL-171.aspx. Cells were propagated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplied with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and cultured in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Vectors, and viruses

To produce lentiviruses based on pLKO, HEK293T cells were transfected with the corresponding pLKO vectors expressing GFP, mcherry, GFP-UL2, mcherry-UL24, or GFP-UL43 together with pVSV-G (expressing the envelope protein of the vesicular stomatitis virus) and pCMV-Δ 9.2 (expressing all necessary lentivirus helper functions) [30] using polyethyleneimine (PEI) as aforementioned [6].

Lentiviruses were collected 48 and 72 h after transfection and used to transduce MRC5 as described [30]. The transduced cells were then selected with puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2–3 days.

Two viruses, ADcre and AD-GFP, were used in this study. ADcre was a lab strain harboring the whole genome of AD169. HCMV AD-GFP, expressing a simian virus 40 (SV40) promoter-driven GFP gene in the lab strain ADcre, was derived from ADcre by BAC recombineering [30, 34].

Viral growth analysis

MRC5 cells were infected with HCMV AD-GFP, AD-dd24, or AD-dd24–dd43 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) (0.1 and 1) for growth analysis for 2 h. The inoculum was then removed, and cells were washed with PBS and replaced with fresh DMEM. Then the cell-free supernatant was collected at the indicated time post-infection, and titers were determined by a 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) assay.

Protein analysis

Protein accumulation was analyzed by immunoblot assay as described protocol [34]. Briefly, cells were collected and lysed in an SDS sample buffer. Proteins were resolved by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, hybridized with primary antibodies, reacted with horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies, and visualized by Clarity western ECL substrate (Bio-Rad).

Protein interactions for the coimmunoprecipitation assay were analyzed as aforementioned [13]. HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and collected after 48 h. Collected cells were lysed in 1 ml lysis buffer (40 mM HEPES [pH7.4], 1 mM EDTA, 300 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP40) supplemented with 250 units of benzonase nuclease and PIC, incubated at 4 ℃ for 1 h, centrifuged at 13,200 × g at 4 °C for 15 min. Forty microliters of the supernatant were saved as the input control and boiled in the sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) containing sample buffer. Then the rest of the supernatant was incubated with FLAG M2 antibody-conjugated magnetic beads (Sigma-Aldrich) at 4 °C for 2 h. The beads were then washed five times with 1 ml lysis buffer. Finally, the samples were eluted with 150 ng/μl FLAG peptide (Sigma-Aldrich), and the input and elution were determined by western blot with the indicated antibody.

For the mass spectrometry (MS) process, the silver stain was performed as described previously [8, 19, 27] (see supplementary Fig. S1). After the electrophoresis, the gel was put into about 100 ml fixative and shaken at room temperature on a shaker for 20 min/60–70 rpm. After washing processes and adding the silver-stained chromogenic solution, the silver-staining solution was discarded. Silver staining stop solution (1×) was added and shaken at room temperature on a shaker for 10 min/60–70 rpm, Finally, discard the silver dye stop solution and wash with double-distilled water, and shake at room temperature on a shaker for 2–5 min/60–70 rpm (see Supplementary Fig. S1). Ultimately, the collected protein bands were sent for the MS detection process.

Subcellular fractionation was generated according to the Nuclear/Cytosol Fractionation Kit (ab289882). 2 × 106 MRC5 cells were infected with HCMV AD169 at an MOI of 1. Cells were collected at indicated time post-infection. For cytosolic fractions, the cells were lysed in 200 μl cytosolic extraction buffer A (CEB-A) Mix (containing DTT and protease inhibitors) and incubated on ice for 10 min. Then 11 µL of ice-cold Cytosol Extraction Buffer-B was added to the tube and incubate on ice for 1 min. For the nuclear fractions, the obtained cell pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of ice-cold Nuclear Extraction Buffer Mix (NEB) and incubated for 40 min on ice (with intermittent mixing) followed by centrifugation at 16,000 g for 10 min. Both obtained fractions were stored at −80 °C for future use. DMSO-treated cells were used as controls.

Confocal microscopy analysis

Cells were seeded on coverslips in a 24-well plate and infected with HCMV at an MOI of 1. Cells were collected at indicated time points and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min. The permeable cells were then blocked with 5% human serum (Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 min to neutralize the Fc epitope in the viral assembly compartment to avoid non-specific antibody binding and then incubated with the primary SAMHD1 Polyclonal Antibody (1:100, rabbit), which was incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The cells were then washed three times with PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies for an hour. The cells were then stained with DAPI (1:5000; Beyotime) for 10 min. The Leica DMI 3000 B fluorescence microscope was used to capture the images.

RNA analysis

MRC5 cells were grown in six-well plates for 48 h and then mocked or infected with HCMV wild type (WT), deleted UL24 (dd24), or double deleted UL24–UL43 (dd24–43) at an MOI of 1. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen). Total mRNAs were collected at the indicated time points post-infection and measured by quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa) using specific primer pairs for the SAMHD1 as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Primers for Quantitative PCR

| Plasmid name | Primer sequence (5'–3') |

|---|---|

| SAMHD1 |

F: CTGACCGGTCAGCGAGCCGATTCCGAGCAGCCCT R:GGAATTCTCACATTGGGTCATCTTTAAAAAG F: TGAGCTCCACCCTCTCCTCGTCCGAATC R: GGCTTGGTGAAATTTCTGTCTGCACACC |

| GAPDH |

F: CTGTTGCTGTAGCCAAATTCGT R: ACCCACTCCTCCACC TTTGAC |

F forward, R reverse

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism v7.02 software ( t-test and 1way-ANOVA) was used to analyze data. P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, * and ns = as non-significant. Each experiment was performed three times on separate days in two biological and two technical replicates but usually representative data from a single experiment are shown.

Results

SAMHD1 protein interacts with viral UL24 protein based on mass spectrometry and immunoprecipitation assay

Previous studies reported that in HCMV infection, the SAMHD1 protein can be regulated directly in the nucleus through the viral product UL97 kinase protein or in the cytoplasm through the CDK-phosphorylation pathway [26, 42], thus through subcellular localization but the viral gene products that may involve in this process remain unknown yet. Therefore, to determine the viral products that may play a role in this pathway in HCMV infection, we first infected the MRC5 cells with AD-HCMV at the multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. The collected cells at 48 h post-infection (hpi) were immunopurified and processed with silver stain and ultimately sent for Mass Spectrometry (MS) analysis. As a result, the viral protein product that was specifically associated with SAMHD1 was UL24, which is a member of the HCMV US22 family (MS data available in supplementary materials). To further confirm this result, we performed a co-immunoprecipitation assay (Co-IP) for the transduced pUL24 gene in MRC5 cells. As shown in Fig. 1a, exogenous flag-sf-GFP or flag-sf-pUL24 were expressed in MRC5 cells. Cell lysates were collected 48 h post-transduction, stained with the polyclonal SAMHD1 antibody, and analyzed by immunoblotting. We demonstrated that the viral pUL24 protein can bind directly with SAMHD1 in transduced cells as compared to controls.

Fig. 1.

SAMHD1 interacts with the C-terminal sequence of the viral UL24 protein. a MRC5 cells were transduced with flag-GFP (control), and flag-pUL24. Cells were collected at 48 h post-transduction, and finally, flag beads were used for co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP). b–e MRC5 cells were transduced with flag-GFP (control), or b flag-pUL24, truncated flag-NC1, or truncated flag-NC2, c flag-pUL24, flag-N-terminal-pUL24, truncated flag-NC3, truncated flag-NC4, or truncated flag-NC5, d flag-pUL24, mutant flag-KRR, mutant flag-G, or mutant flag-QH, e flag-pUL24, or mutant flag-KGRQHR. The cell lysate was collected at the indicated times post-infection and the protein levels were analyzed by immunoblotting

Furthermore, to understand the essential protein binding sequence site of pUL24 with the SAMHD1 protein that may have some importance in the future study, we constructed a truncation for viral gene product UL24 in several portions based on the prediction of the secondary structure of the viral UL24 protein. At first, we preferred to divide the pUL24 protein sequences into the N and C-terminal portions, but the C-terminal part could not be expressed (data not shown), suggesting that the N-terminal is an essential part of the pUL24 gene. Therefore, we provided several truncations of the N-terminal plus a part of the C-terminal portion known as N-terminal plus C-terminal part one (NC1), N-terminal plus C-terminal part two (NC2), N-terminal plus C-terminal part three (NC3), N-terminal plus C-terminal part four (NC4), and N-terminal plus C-terminal part five (NC5). At first, we transduced MRC5 cells with flag-sf-GFP (control), Whole flag-sf-pUL24, flag-N-terminal-pUL24, flag- NC1, or flag-NC2. Cells were collected at 48 h post-expression and finally stained and immunopurified with SAMHD1 and FLAG antibodies. Only the whole flag-sf-pUL24 (complete pUL24 sequences) protein was associated with SAMHD1 (Fig. 1b). Similar experiments were applied with other UL24 truncation parts (flag-NC3, flag-NC4, or flag-NC5), and only whole flag-sf-pUL24 interacted with SAMHD1 protein, i.e., the last remaining six amino acids (KGRQHR) of pUL24 viral product (Fig. 1c). To confirm that, we altered (mutated) the KGRQHR amino acids separately into alanine amino acids as KRR = AAA, G = A, QH = AA (Fig. 1d), and all were transduced into MRC5 cells along with flag-sf-GFP and whole flag-sf-pUL24 as controls. Interestingly, all mutated pUL24 products could still bind to SAMHD1 protein. To further confirm this, we altered all (KGRQHR) amino acids into AAAAAA alanine amino acid and then transduced along with flag-sf-GFP and whole flag-sf-pUL24 as controls (Fig. 1e). as a result, the mutated AAAAAA-pUL24 lost binding to the SAMHD1 protein compared to flag-sf-pUL24 (positive control). Collectively, these data that these (KGRQHR) amino acids are essential for UL24-SAMHD1 interaction.

-

2.

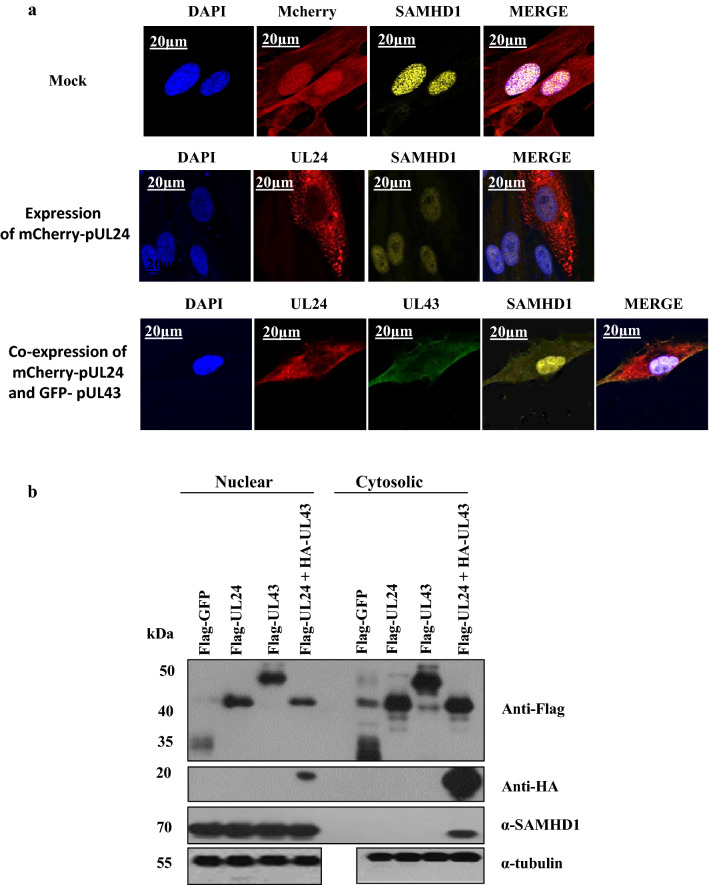

The co-expression of viral gene products pUL24 and pUL43 induces SAMHD1 cytosolic localization

To determine the effect of viral gene product UL24 on the subcellular localization of SAMHD1 during HCMV infection, we first transduced MRC5 cells with plko-mCherry (control), or mCherry-pUL24 gene product. Cells were collected at 48 h post-expression. Like the control cells, the mCherry-pUL24 product did not induce SAMHD1 cytosolic translocation upon microscopic examination (Fig. 2a). This result raises the possibility that pUL24 may cooperate with other viral genes to induce the subcellular localization of SAMHD1 in the HCMV-infected cells.

Fig. 2.

The co-expression of viral gene products UL24 and UL43 affects the SAMHD1 cytosolic translocation. a MRC5 cells were expressed with PLKO-mCherry(control), mCherry-pUL24, or coexpressed with the mCherry-pUL24 + GFP-pUL43 products. Cells were fixed at 48 h post-transduction and stained with antibodies against SAMHD1 and examined under confocal microscopy. Error bar is shown to indicate the scale.Representative data of a single experiment are shown. b MRC5 cells were transduced with Flag-GFP (Ctrl), Flag-UL24, Flag-UL43, or Flag-UL24 + HA-UL43. Cells were collected at 48 h post-transduction. Cytosolic and nuclear levels of SAMHD1 protein were analyzed by immunoblotting. Representative data of a single experiment are shown

According to previous studies, the viral proteins UL24 and UL43 are associated with each other, both members of the HCMV US22 family [36]. To confirm that, we first coexpressed a Flag-pUL24 and HA-pUL43 and then used Flag beads for the co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay. We demonstrated that the viral HA-UL43 product was precipitated by Flag-pUL24 protein (data is not shown). To determine whether the coexpression of viral UL24 and UL42 products induce the subcellular localization of SAMHD1, MRC5 cells were transduced with plko-mCherry (control), mCherry-pUL24, or mCherry-pUL24 and GFP-pUL43. At 48 h post-transduction, cells were fixed and stained with antibodies against SAMHD1 protein and ultimately examined under confocal microscopy. Interestingly, the coexpression of both viral UL24 and UL43 products induced the cytoplasmic relocalization of SAMHD1, whereas the expression of mCherry-pUL24 alone did not (Fig. 2a). To further confirm this result, we overexpressed the MRC5 cells with Flag-GFP (Control), Flag-UL24, Flag-UL43, or coexpressed Flag-UL24 + HA-UL43 viral products. Cells were collected 48 h post-expression. Cytosolic and nuclear levels of SAMHD1 protein were analyzed by immunoblotting. As compared to Control (Flag-GFP), only the coexpressed Flag-UL24 + HA-UL43 viral products induced the cytosolic protein expression in the transduced cells, while the rest of the viral products were not (Fig. 2b). Collectively, these results suggest that the viral gene products, UL24 and UL43, may cooperate to regulate SAMHD1 activity through subcellular localization.

-

3.

Double knockout of viral UL24 and UL43 gene products induce SAMHD1 nuclear accumulation in the infected cells

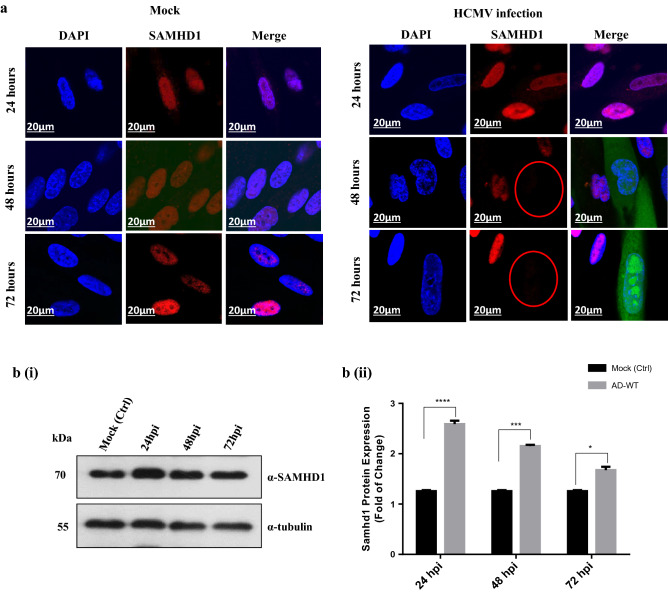

To further confirm the correlation between SAMHD1 cytoplasmic relocalization and UL24 and UL43 viral products, we first checked the cellular localization of SAMHD1 during early and late HCMV infection in MRC5 cells under confocal microscopy. Cells were mock infected or HCMV infected (GFP-tagged HCMV) with MOI of 1 and then collected at different times post-infection and cell lysates were stained against polyclonal SAMHD1 antibodies. Similar to the control cells, SAMHD1 protein, which is normally an intranuclear protein, was still visible in the nuclei in the early stage, 24 h post-infection (hpi) upon microscopic examination but it disappeared at the late stage post-infection (48–72 hpi) (Fig. 3a). To check the effect of HCMV infection on the SAMHD1 expression level, we performed immunoblotting (Fig. 3b-i) and relative density of SAMHD1 protein expression (Fig. 3b-ii) of the whole-cell extracts from the control cells (mock-infected) or HCMV-infected cells at the indicated times post-infection. We demonstrate that the level of the SAMHD1 protein was more significantly increased at the early 24 hpi followed by gradual depletion in the later time (48 and 72 hpi) in the infected cells This result is not surprising since similar results have been reported earlier in HCMV infection in the cells of fibroblast origin [26, 42].

Fig. 3.

The viral UL24 and UL43 products affect the expression and cytosolic localization of SAMHD1 protein in HCMV infected cells. a MRC5 cells were infected with GFP-HCMVAD creat a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. Cells were fixed at the indicated times post-infection. Cells were stained with antibodies against SAMHD1 protein and examined under confocal microscopy. Error bar is shown to indicate the scale. bi-ii MRC5 cells were mock-infected or infected with Flag-HCMVAD creat MOI of 1. Cells were collected at the indicated times post-infection. Immunoblots (i) and relative density showing protein expression of SAMHD1 (ii) were analyzed. Representative data of two independent experiments are shown. Error bars represent SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 vs mock (control) as per one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons c MRC5 cells were mock or infected with AD-GFP-dd24, AD-GFP-dd24 + dd43, or AD-GFPHCMV(AD-WT). Cells were fixed at the indicated time post-infection, stained with antibodies against SAMHD1, and examined under confocal microscopy. AD-GFPHCMV(AD-WT) = HCMVDA169 wildtype, AD-GFP-dd24 = recombinant HCMV deleted UL24 gene, and AD-GFP-dd24–dd43 = recombinant HCMV double deleted UL24 and UL43 genes. Errorbar is shown to indicate the scale. d MRC5 cells were DSMO-infected (as a controls), infected with AD-dd24, AD-dd24 + dd43, or AD-HCMV wildtype (Ad-WT). Cells were collected at 72 hpi, and the nuclear/cytoplasmic fractions were processed according to the manufacture, and ultimately Immunoblots (i) and relative density showing protein expression of SAMHD1 (ii) were analysed. Results are representative of three independent experiments. Errorbars represent SEM. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001 vs DMSO-infected (control) as per one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons

Next, to further explore the involvement of the viral gene products, pUL24 and pUL43, in subcellular localization, MRC5 cells were DSMO-treated (control) or infected with the AD-GFP HCMV wild type (AD-WT), AD-GFP HCMV deleted UL24 gene (AD-dd24), or AD-GFP HCMV double deleted UL24 + UL43 gene products (AD-dd24 + dd43) at MOI of 1. Cells were stained with the polyclonal SAMHD1 antibody and examined under confocal microscopy. interestingly, the double deleted-pUL24 and UL43 genes (termed AD-dd24 + dd43) at least induced the partial nuclear retention of SAMHD1 protein and reduced its cytosolic relocalization in the infected cells as compared with the AD-GFP HCMV and AD-GFP-dd24 at the late stage of infection (Fig. 3c). Also, we performed subcellular fractionation to obtain nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions from the HCMV AD-WT, AD-dd24–dd43, and AD-dd24 infected and control cells at 72 h post-infection (hpi). As shown in Fig. 3d (i) and d (ii), immunoblotting of cytosolic fractions revealed a significant depletion in the SAMHD1 protein levels in the infected double deleted UL24 + UL43 gene products (AD-dd24 + dd43) as compared to the HCMV wild type (AD-WT) and HCMV deleted UL24product (AD-dd24). These data further support the participation of viral UL24 and UL43 gene products in the subcellular localization of SAMHD1 during HCMV infection.

Note The growth curve for both AD-GFP-dd24 (HCMV AD-deleted-pUL24 gene) and AD-GFP-dd24 + dd43 (HCMV-AD double deleted pUL24 and pUL43 genes) were checked and the viral titers were determined by tissue culture infectious dose 50% (TCID50). HCMV AD-GFP was used as a control. Compared with the control, the viral growth and replication in both AD-GFP-dd24 and AD-GFP-dd2 + −dd43 were not affected at low and high MOI during the whole indicated time of infection (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Discussion

Recently, a study has identified SAMHD1 as a host restriction factor blocking the early stage of viral DNA synthesis in HCMV infection via the NF-kB restriction pathway [17]. In contrast, other reports revealed that HCMV can overcome the restriction activity of SAMHD1 protein through various strategies. Inside the nucleus, the HCMV phosphorylates SAMHD1 protein directly by a viral protein kinase UL97 and reduces its antiviral effect. The HCMV also limits the activity of SAMHD1 through cytoplasmic relocalization mediated by CDK post-translational phosphorylation at T592 residue but the viral gene products that participate in this process are not studied yet.

Therefore, in this report, we checked the possibility of viral gene product involvement in subcellular localization. Based on MS data and co-immunoprecipitation assay, the viral UL24 tegument protein, the HCMV US22 family member, was among the viral products associated explicitly with SAMHD1 protein in the infected MRC5 cells. Moreover, upon subsequent truncations of the viral UL24 protein, we demonstrated that the SAMHD1 protein interacted with the C-terminal portion UL24 (KGRQHR).

This result suggests that the viral UL24 gene product may induce SAMHD1 cytosolic translocation in infected cells through its bindings. To address that, we overexpressed the viral pUL24 gene in MRC5 cells. The results of immunoblotting and confocal microscopy revealed that the viral UL24 gene did not produce a considerable effect on SAMHD1 protein expression and its subcellular localization. This raises the possibility that the UL24 gene product may cooperate with other viral or cellular factors to enhance the SAMHD1 subcellular localization in HCMV-infected cells. Previous studies described that UL24 and UL43 protein products, both members of the HCMV US22 family, can interact with each other during HCMV infection [36]. To confirm that, we co-expressed Flag-UL24 and HA-UL43 in MRC5 cells. The coimmunoprecipitation results showed that UL24 precipitated UL43 as previously reported. Furthermore, to assess whether UL24 and UL43 gene products can cooperate to induce the subcellular localization of the SAMHD1 protein in infected cells, we co-expressed the viral UL24 and UL43 gene products in MRC5 cells. Based on the microscopical examination, the co-expressed viral products induced the cytoplasmic translocation of the SAMHD1 protein partially. To confirm this result, we first constructed BAC-deleted HCMV gene products UL24 and UL43, (HCMV deleted UL24 termed AD dd24, and HCMV double deleted the UL24–UL43 genes termed AD dd24–dd43). The effects of the AD-dd24 and AD-dd24–dd43 genes on the expression and localization of the SAMHD1 protein were evaluated by microscopic examination and immunoblotting analysis in infected cells. The microscopic examinations revealed that the double deleted viral UL24 and UL43 products (AD-dd24 + dd43) induced nuclear relocalization of SAMHD1 infected cells compared to HCMV wild type and deleted UL24 product infected cells. Also, the immunoblotting result of cytosolic fractions revealed that the SAMHD1 expression was severely declined in HCMV double deleted viral gene products (AD-dd24 + dd43) infected cells, especially at the late time of infection as compared with wild-type(AD-WT) and UL24 deleted HCMV (AD-dd24) infected cells. This was consistent with nuclear retention in the case of dd24–dd43 HCMV in the late stage of HCMV infection. Collectively, our data reveal that UL24 and UL43 may enhance SAMHD1 cytosolic relocalization to regulate its restriction activity during HCMV infection.

Limitations of the study

We demonstrate that viral UL24–UL43 proteins may facilitate the subcellular localization but to determine the mechanism of how UL24 and UL43 products cooperate to enhance the SAMHD1 subcellular localization in HCMV infection will need further experiments in the future.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the Herpesvirus and Molecular Virology Research Unit members for the helpful discussion and Roger Everett (University of Glasgow) for the pLKO-based lentiviral expression system.

Abbreviations

- HCMV AD169

Human cytomegalovirus strain AD169

- AGS

Aicardi-Goutie'res syndrome

- ATCC

American Type Culture Collection

- BAC

Bacterial Artificial Chromosome

- HCMV dd24

Human cytomegalovirus with deleted UL24 gene

- HCMV dd24–dd43

Human cytomegalovirus with double deleted UL24 and UL43 genes

- CD81

Cluster of Differentiation 81

- CDK1

Cyclin-dependent kinase 1

- CoIP

Co-immunoprecipitation

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- dNTP

Deoxynucleoside triphosphate

- ECL

Electrochemiluminescence

- EDTA

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- GFP

Green fluorescent protein

- HCMV

Human cytomegalovirus

- HEK

Human Embryonic Kidney Cells

- HEPES

4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- hpi

Hours post-infection

- HSV

Herpes Simplex Virus

- IFN

Interferon

- NF-kB

Nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells

- MOI

Multiplicity of infection

- MS

Mass spectrometry

- PEI

Polyethyleneimine

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- SAMHD1

SAM and HD Domain Containing Deoxynucleoside Triphosphate Triphosphohydrolase 1

- SDS

Sodium dodecyl sulfate

- SV40

Simian virus 40

- TCID50

Tissue culture infectious dose

- UL

Unique long

- WT

Wild type

Funding

This work was supported by the China National Natural Science Foundation (Grants 81371826 and 81572002 to ZQ. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Declaration

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Aravind L, Koonin EV. The HD domain defines a new superfamily of metal-dependent phosphohydrolases. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:469–472. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(98)01293-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayinde D, Casartelli N, Schwartz O. Restricting HIV the SAMHD1 way: through nucleotide starvation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:675–680. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badia R, Angulo G, Riveira-Muñoz E, Pujantell M, Puig T, Ramirez C, Torres-Torronteras J, Martí R, Pauls E, Clotet B. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus type 1 by the CDK6 inhibitor PD-0332991 (palbociclib) through the control of SAMHD1. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:387–394. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beloglazova N, Flick R, Tchigvintsev A, Brown G, Popovic A, Nocek B, Yakunin AF. Nuclease activity of the human SAMHD1 protein implicated in the Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome and HIV-1 restriction. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:8101–8110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.431148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger A, Sommer AF, Zwarg J, Hamdorf M, Welzel K, Esly N, Panitz S, Reuter A, Ramos I, Jatiani A. SAMHD1-deficient CD14+ cells from individuals with Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome are highly susceptible to HIV-1 infection. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002425. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boussif O, Lezoualc'h F, Zanta MA, Mergny MD, Scherman D, Demeneix B, Behr J-P. A versatile vector for gene and oligonucleotide transfer into cells in culture and in vivo: polyethylenimine. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:7297–7301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Z, Zhu M, Pan X, Zhu Y, Yan H, Jiang T, Shen Y, Dong X, Zheng N, Lu J. Inhibition of Hepatitis B virus replication by SAMHD1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;450:1462–1468. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chevallet M, Luche S, Rabilloud T. Silver staining of proteins in polyacrylamide gels. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(4):1852–1858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clifford R, Louis T, Robbe P, Ackroyd S, Burns A, Timbs AT, Wright Colopy G, Dreau H, Sigaux F, Judde JG. SAMHD1 is mutated recurrently in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and is involved in response to DNA damage. Blood J Am Soc Hematol. 2014;123:1021–1031. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-490847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cribier A, Descours B, Valadão ALC, Laguette N, Benkirane M. Phosphorylation of SAMHD1 by cyclin A2/CDK1 regulates its restriction activity toward HIV-1. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1036–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crow YJ, Rehwinkel J. Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome and related phenotypes: linking nucleic acid metabolism with autoimmunity. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:R130–R136. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Meo S, Dell'Oste V, Molfetta R, Tassinari V, Lotti LV, Vespa S, Pignoloni B, Covino DA, Fantuzzi L, Bona R, Zingoni A, Nardone I, Biolatti M, Coscia A, Paolini R, Benkirane M, Edfors F, Sandalova T, Achour A, Hiscott J, Landolfo S, Santoni A, Cerboni C. SAMHD1 phosphorylation and cytoplasmic relocalization after human cytomegalovirus infection limits its antiviral activity. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 28;16(9):e1008855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Goldstone DC, Ennis-Adeniran V, Hedden JJ, Groom HC, Rice GI, Christodoulou E, Walker PA, Kelly G, Haire LF, Yap MW. HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a deoxynucleoside triphosphate triphosphohydrolase. Nature. 2011;480:379–382. doi: 10.1038/nature10623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han T, Hao H, Sleman SS, Xuan B, Tang S, Yue N, Qian Z. Murine Cytomegalovirus Protein pM49 Interacts with pM95 and Is Critical for Viral Late Gene Expression. J Virol. 2020;94(6):e01956–e2019. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01956-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollenbaugh JA, Gee P, Baker J, Daly MB, Amie SM, Tate J, Kasai N, Kanemura Y, Kim D-H, Ward BM. Host factor SAMHD1 restricts DNA viruses in non-dividing myeloid cells. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003481. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hrecka K, Hao C, Gierszewska M, Swanson SK, Kesik-Brodacka M, Srivastava S, Florens L, Washburn MP, Skowronski J. Vpx relieves inhibition of HIV-1 infection of macrophages mediated by the SAMHD1 protein. Nature. 2011;474:658–661. doi: 10.1038/nature10195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karstentischer B, von Einem J, Kaufer B, Osterrieder N. Two-step red-mediated recombination for versatile high-efficiency markerless DNA manipulation in Escherichia coli. Biotechniques. 2006;40:191–197. doi: 10.2144/000112096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim CA, Bowie JU. SAM domains: uniform structure, diversity of function. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:625–628. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kretschmer S, Wolf C, König N, Staroske W, Guck J, Häusler M, Luksch H, Nguyen LA, Kim B, Alexopoulou D. SAMHD1 prevents autoimmunity by maintaining genome stability. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:e17–e17. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar G. Principle and method of silver staining of proteins separated by sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1853:231–236. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8745-0_26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laguette N, Benkirane M. How SAMHD1 changes our view of viral restriction. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laguette N, Sobhian B, Casartelli N, Ringeard M, Chable-Bessia C, Ségéral E, Yatim A, Emiliani S, Schwartz O, Benkirane M. SAMHD1 is the dendritic-and myeloid-cell-specific HIV-1 restriction factor counteracted by Vpx. Nature. 2011;474:654–657. doi: 10.1038/nature10117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lahouassa H, Daddacha W, Hofmann H, Ayinde D, Logue EC, Dragin L, Bloch N, Maudet C, Bertrand M, Gramberg T. SAMHD1 restricts the replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by depleting the intracellular pool of deoxynucleoside triphosphates. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:223–228. doi: 10.1038/ni.2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landolfo S, De Andrea M, Dell'Oste V, Gugliesi F. Intrinsic host restriction factors of human cytomegalovirus replication and mechanisms of viral escape. World J Virol. 2016;5:87. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v5.i3.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim YW, Sanz LA, Xu X, Hartono SR, Chédin F. Genome-wide DNA hypomethylation and RNA: DNA hybrid accumulation in Aicardi-Goutières syndrome. Elife. 2015;4:e08007. doi: 10.7554/eLife.08007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mashiba M, Collins KL. Molecular mechanisms of HIV immune evasion of the innate immune response in myeloid cells. Viruses. 2013;5:1–14. doi: 10.3390/v5010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merril CR, Goldman D, Sedman SA, Ebert MH. Ultrasensitive stain for proteins in polyacrylamide gels shows regional variation in cerebrospinal fluid proteins. Science. 1981;211(4489):1437–1438. doi: 10.1126/science.6162199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan X, Baldauf H-M, Keppler OT, Fackler OT. Restrictions to HIV-1 replication in resting CD4+ T lymphocytes. Cell Res. 2013;23:876–885. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powell RD, Holland PJ, Hollis T, Perrino FW. Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome gene and HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a dGTP-regulated deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:43596–43600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C111.317628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qian Z, Xuan B, Hong TT, Yu D. The full-length protein encoded by human cytomegalovirus gene UL117 is required for the proper maturation of viral replication compartments. J Virol. 2008;82:3452–3465. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01964-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rice GI, Bond J, Asipu A, Brunette RL, Manfield IW, Carr IM, Fuller JC, Jackson RM, Lamb T, Briggs TA. Mutations involved in Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome implicate SAMHD1 as regulator of the innate immune response. Nat Genet. 2009;41:829–832. doi: 10.1038/ng.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rocha-Perugini V, Suárez H, Álvarez S, López-Martín S, Lenzi GM, Vences-Catalán F, Levy S, Kim B, Muñoz-Fernández MA, Sánchez-Madrid F. CD81 association with SAMHD1 enhances HIV-1 reverse transcription by increasing dNTP levels. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:1513–1522. doi: 10.1038/s41564-017-0019-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sommer AF, Rivière L, Qu B, Schott K, Riess M, Ni Y, Shepard C, Schnellbächer E, Finkernagel M, Himmelsbach K. Restrictive influence of SAMHD1 on Hepatitis B Virus life cycle. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–14. doi: 10.1038/srep26616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terhune S, Torigoi E, Moorman N, Silva M, Qian Z, Shenk T, Yu D. Human cytomegalovirus UL38 protein blocks apoptosis. J Virol. 2007;81:3109–3123. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02124-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tischer BK, Smith GA, Osterrieder N: En passant mutagenesis: a two step markerless red recombination system. In: In vitro mutagenesis protocols. Springer; 2010: 421–30 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.To A, Bai Y, Shen A, Gong H, Umamoto S, Lu S, Liu F. Yeast two hybrid analyses reveal novel binary interactions between human cytomegalovirus-encoded virion proteins. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(4):e17796. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner M, Jonjić S, Koszinowski UH, Messerle M. Systematic excision of vector sequences from the BAC-cloned herpesvirus genome during virus reconstitution. J Virol. 1999;73:7056–7060. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.8.7056-7060.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J-l, Lu F-z. Shen X-Y, Wu Y, Zhao L-t: SAMHD1 is down regulated in lung cancer by methylation and inhibits tumor cell proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;455:229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.10.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White TE, Brandariz-Nuñez A, Valle-Casuso JC, Amie S, Nguyen LA, Kim B, Tuzova M, Diaz-Griffero F. The retroviral restriction ability of SAMHD1, but not its deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase activity, is regulated by phosphorylation. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:441–451. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan J, Kaur S, DeLucia M, Hao C, Mehrens J, Wang C, Golczak M, Palczewski K, Gronenborn AM, Ahn J. Tetramerization of SAMHD1 is required for biological activity and inhibition of HIV infection. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:10406–10417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.443796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu D, Smith GA, Enquist LW, Shenk T. Construction of a self-excisable bacterial artificial chromosome containing the human cytomegalovirus genome and mutagenesis of the diploid TRL/IRL13 gene. J Virol. 2002;76:2316–3232. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2316-2328.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang K, Lv D-W, Li R. Conserved herpesvirus protein kinases target SAMHD1 to facilitate virus replication. Cell Rep. 2019;28(449–459):e445. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.