Abstract

The three proteins of the antigen 85 complex (85A, 85B, and 85C), which are major secretory products of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, were purified to homogeneity in large amounts by a combination of chromatography on hydroxylapatite, DEAE-Sepharose, and DEAE-Sephacel and gel filtration from M. tuberculosis culture filtrate. Then we examined the immunological reactivity of the three proteins in tuberculosis patients and healthy controls. Antibody responses to the 85B and 85A proteins in patients were significantly greater than responses to the 85C protein. In contrast, all three antigens induced significant lymphoproliferation and gamma interferon production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy tuberculin reactors.

The 30/32-kDa antigen 85 (Ag85) complex has been the focus of intensive research over the past several years and comprises three closely related proteins, 85A (32 kDa), 85B (30 kDa), and 85C (32.5 kDa) (17, 25–27). The Ag85 complex induces protective immunity against tuberculosis (TB) in guinea pigs (7), and strong T-cell proliferation and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from healthy tuberculin reactors (6, 8, 21). In this regard, this complex is a candidate for a novel TB vaccine. There may be differences in the T-cell-stimulating capacities and antibody reactivity of the individual components of the Ag85 complex (14, 15, 18, 23–25). However, because these antigens are difficult to purify in large amounts by biochemical techniques, very limited information on differences in cellular and humoral immune responses to each of the three components of the native Ag85 complex is available. In particular, the 85C protein is quantitatively minor and has not been well characterized by other investigators. Therefore, we purified the three components of the Ag85 complex from Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture filtrates (CF) by biochemical methods. Then, immunological reactivity against these purified antigens in TB patients and healthy volunteers was evaluated by measuring specific serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody levels and lymphoproliferation and IFN-γ production of PBMC stimulated with the antigens.

Sera.

Sera were collected from two groups. One test group consisted of 42 patients with pulmonary TB who had been admitted at the National Masan Tuberculosis Hospital, Masan, Korea, and had been receiving therapy for over 2 months. A diagnosis of TB was based upon a clinical evaluation, a sputum smear and culture, and/or a chest X-ray. The other group consisted of 20 patients with pulmonary TB who were outpatients at the Taejeon Sungmo Hospital, Taejeon, Korea. All of these 20 outpatients received standard chemotherapy for 6 months. Sera were taken serially from these patients before treatment began and at about 2 and 6 months after the initiation of chemotherapy. The healthy control sera were obtained from 104 students of the Chungnam National University, Taejeon, Korea.

Purification of the 85A, 85B, and 85C proteins.

M. tuberculosis H37Rv (ATCC 27294) was grown for 6 weeks at 37°C as a surface pellicle on Sauton medium. The CF was sterilely filtered and precipitated with ammonium sulfate (55% saturation), and the resulting precipitate was dissolved and dialyzed against 1 mM sodium phosphate buffer (PB) (pH 6.8). Protein concentrations were determined by a protein assay kit (Pierce) with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard.

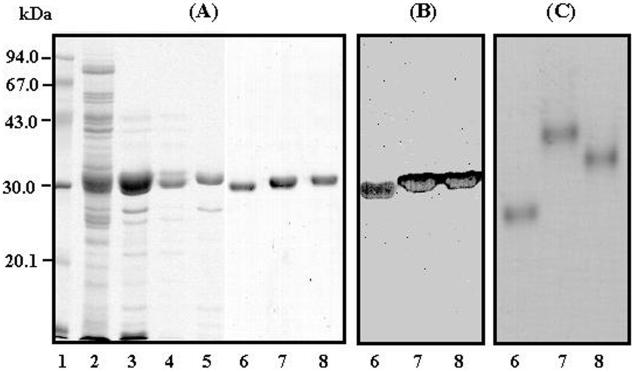

The 55% ammonium sulfate fraction of the CF was applied to a column of hydroxylapatite (Bio-Rad) equilibrated with 1 mM PB (pH 6.8) and eluted with 1 mM PB because the Ag85 complex was not retained on the column (11, 26). Initially, to separate the 30-kDa (85B) and 32-kDa (85A and 85C) proteins, the fractions excluded from the hydroxylapatite column were applied to a column of DEAE-Sepharose CL-6B (Sigma) equilibrated with 1 mM PB (pH 7.2). The 32-kDa (85A) and 32.5-kDa (85C) proteins were coeluted with 5 mM PB (Fig. 1A, lane 5), and the 30-kDa protein (85B) was eluted with 10 mM PB (Fig. 1A, lane 4). The 85A and 85C proteins were further separated by DEAE-Sephacel (Pharmacia). The 85A protein was eluted first from DEAE-Sephacel with 20 mM Tris-HCl, followed by the 85C protein. On the other hand, the fractions from the DEAE-Sepharose column enriched for the 85B protein were dialyzed against 5 mM PB (pH 6.8) and then also applied to a DEAE-Sephacel column to remove contaminated 32-kDa protein and other proteins. The 85B protein was eluted with 10 mM PB from DEAE-Sephacel. The analysis of eluted fractions was performed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and natural PAGE. SDS-PAGE was performed in a discontinuous buffer system by the method of Laemmli (12). For natural PAGE, the same gel system was used, except that SDS and 2-mercaptoethanol were omitted from all buffers. Each fraction from the DEAE-Sephacel column enriched for the 85B, 85A, and 85C proteins was pooled and concentrated, separately.

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE (A), immunoblotting (B), and natural PAGE (C) analyses of the purified 85A, 85B, and 85C proteins. Lane 1, low molecular weight marker. Lanes 2 through 5, products from different stages of purification, as follows. The 55% ammonium sulfate fraction (lane 2) of CF was applied to a hydroxylapatite column, and then the column was washed with 1 mM PB (pH 6.8). All pass-through fractions were pooled (lane 3) and then applied to a DEAE-Sepharose column. The eluate fractions from DEAE-Sepharose with 5 mM PB (lane 5) and 10 mM PB (lane 4) were dialyzed against 10 mM NaCl–20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) and 5 mM PB (pH 6.8), respectively, and applied to a DEAE-Sephacel column. Final purification was performed by gel filtration on Superdex 75. The antigens were separated by SDS-PAGE and natural PAGE and then analyzed by Coomassie blue staining and immunoblotting with monoclonal antibody HYT27. Lanes 6 to 8, purified 85B, 85A, and 85C proteins, respectively.

Finally, the three proteins were purified by gel filtration on Superdex 75 (Pharmacia). Each protein yielded a single band on SDS-PAGE and natural PAGE gels stained with Coomassie blue (Fig. 1A and C, lanes 6, 7, and 8). The monoclonal antibody HYT27 (provided by the United Nations Development Program/World Bank/World Health Organization Special Program for Research and Training in Tropical Disease), which is specific to the Ag85 complex, reacted strongly with the three proteins (Fig. 1B). Immunoblotting analysis was performed as described previously (10). In one experiment we purified 1.52, 1.89, and 0.55 mg of 85B, 85A, and 85C, respectively, from 484 mg of the 55% ammonium sulfate fraction of the CF.

Antibody responses to the three proteins.

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for antibody determination was performed as described previously (11). Polystyrene 96-well microplates were coated overnight with each protein at 1.0 μg/ml (0.1 ml/well) in 0.05 M carbonate buffer (pH 9.6). Each well was blocked with 1% BSA in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-Tween 20), and incubated with 0.1 ml of serum diluted 1:200 in 1% BSA–PBS–Tween 20 for 1 h at 37°C. After washing, the plates were incubated with 0.1 ml of peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Sigma) diluted 1:3,000 in 0.1% BSA–PBS–Tween 20 for 1 h at 37°C. Color development was performed by adding O-phenylenediamine at 0.4 mg/ml in 0.05 M citrate-phosphate buffer (pH 5.0) containing 0.03% H2O2. After 30 min, the reactions were stopped with 8 N H2SO4 and the A492 was measured in an ELISA reader (Spectra Max Plus; Molecular Devices).

The levels of IgG antibodies to the three proteins were measured in sera from TB patients treated for at least 2 months and from healthy subjects (Table 1). There was a wide variation in antibody content in sera from individual patients. Antibody responses to the 85A and 85B proteins in patients were significantly greater than those to the 85C protein (P < 0.05), but no significant difference between the mean levels of IgG antibody in response to the 85A and 85B proteins was observed. Twenty patients were also tested before treatment began and at 2 and 6 months after initiation of treatment (Table 2). These patients had been treated successfully by standard chemotherapy for 6 months. The mean IgG antibody levels against all antigens increased significantly at about 2 months after the start of chemotherapy (P < 0.05), and then antibody levels declined by about 30% at 6 months after the start of chemotherapy. However, some patients showed a steady increase or plateau in antibody levels until 6 months. These results are in good agreement with those previously obtained with the P32 antigen (22) and may be due to the release of increasing amounts of antigen as mycobacteria are destroyed by antituberculous drugs (9). One investigation has indicated that exposure to isoniazid induces the expression of several secreted proteins, including the Ag85 complex, in M. tuberculosis (4).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of IgG antibody responses to 85A, 85B, and 85C proteins in TB patients and healthy controls

| Group (no. of subjects) | ELISA resultsa for:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 85B

|

85A

|

85C

|

||||

| Mean OD492 (SD) | No. of positiveb serum samples | Mean OD492 (SD) | No. of positive serum samples | Mean OD492 (SD) | No. of positive serum samples | |

| TB patients (42) | 1.01 (0.79)* | 32 | 1.13 (0.98)* | 21 | 0.26 (0.24)* | 5 |

| Healthy controls (104) | 0.11 (0.11) | 3 | 0.19 (0.18) | 3 | 0.14 (0.13) | 1 |

Sera were collected from both TB patients who had been treated for at least 2 months and healthy controls and were diluted 1:200. *, Student's t test for significance of difference (in comparison with healthy controls) yielded P values of <0.001 for all tested antigens.

Cutoff value for each antigen was calculated as the mean optical density at 492 nm (OD492) obtained with sera from 104 healthy controls, plus three standard deviations.

TABLE 2.

IgG antibody level changes in TB patients following start of chemotherapy

| Antigen | OD492 ata:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mo | 2 mo | 6 mo | |

| 85B | 0.42 ± 0.57 a | 0.83 ± 0.79 b | 0.61 ± 0.57 a |

| 85A | 0.49 ± 0.55 a | 0.97 ± 0.79 b | 0.68 ± 0.58 a |

| 85C | 0.17 ± 0.15 a | 0.32 ± 0.26 b | 0.20 ± 0.19 a |

Values are means ± standard deviations for IgG antibody in 20 TB patients treated with a standard drug regimen. Duncan's test for multiple comparisons of means was used to determine whether there were any significant differences between results for different durations of chemotherapy. The letters a and b indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05) between results for a given antigen.

Proliferative responses and IFN-γ production due to the three proteins.

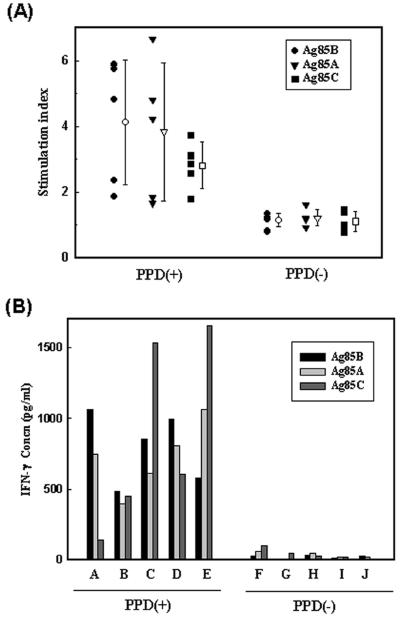

To evaluate the immunoreactivity of 85A, 85B, and 85C, we measured the proliferative responses and IFN-γ production levels of PBMC from five tuberculin-positive and five tuberculin-negative healthy subjects. Lymphocyte proliferation assays were performed as described previously (10). IFN-γ levels from culture supernatants after 96 h were determined by ELISA with a commercial kit for human cytokines (PharMingen). As shown in Fig. 2, proliferative responses and IFN-γ production levels in response to all three antigens were significantly greater in healthy tuberculin reactors than in negative subjects (P < 0.05), although individual reactive patterns showed considerable variation. These results are consistent with the human studies of others (8, 20, 21). Previous studies also indicate that immunological reactivities to mycobacterial antigens in human subjects are highly heterogenous (6, 8, 13, 16, 19, 20).

FIG. 2.

Lymphoproliferation (A) and IFN-γ production (B) in response to the 85B, 85A, and 85C proteins. (A) PBMC from five healthy purified protein derivative (PPD)-positive [PPD(+)] subjects (designated by the letters A through E) and five PPD-negative [PPD(−)] subjects (designated by the letters F through J) were stimulated with each of the three antigens (1.0 μg/ml) for 5 days, and incorporation of [3H]thymidine was measured. The results were expressed as a stimulation index (defined as counts per minute in antigen-stimulated cultures/counts per minute in unstimulated cultures). Error bars represent standard deviations from the means (open symbols [as for closed symbols, respective shapes show results for individual antigens]). (B) Supernatants from antigen-stimulated PBMC were collected after 96 h and assayed for IFN-γ production by ELISA.

The Ag85 complex proteins, 85A, 85B, and 85C, share high sequence homology at the nucleotide and protein levels both with each other and with Ag85 from other mycobacterial species (2, 5). The 85A and 85B proteins have been purified independently by different workers (3, 7, 17, 26). Because the 85A and 85C proteins had slightly different molecular masses, they could not be isolated in large amounts by gel filtration and were clearly resolved by natural PAGE. DEAE-Sephacel was therefore included in the purification procedure to ensure a good separation of the two antigens from each other. Interestingly, 85A and 85C were eluted in that order from DEAE-Sephacel with 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 10 mM NaCl.

The relationship between the individual components of the Ag85 complex is of the greatest interest. In fact, comparison of the immune responses to the 85A and 85B proteins in human and animal models have been analyzed by different workers (17, 18, 23). However, detailed immunoreactivity studies of all three native proteins have not been carried out. In this work, sensitivities of 76, 50, and 12% for 85B, 85A, and 85C, respectively, were shown, which is surprising, considering the high level of homology between these proteins. The 85B protein was more valuable in the diagnosis of TB than 85A because antibody reactivities to 85A were much higher than those to 85B in healthy controls as well as TB patients. These results are in agreement with the findings of previous studies using 85A and 85B (18, 22–24). Interestingly, significantly lower antibody levels against the 85C protein were observed in our patients. The differences in antibody reactivity among the three antigens may be due to differences in their immunogenicity, in the composition of the Ag85 complex (5) and in antigen availability in vivo or in their capacities to form complexes with IgG and fibronectin in circulation (1).

In contrast to antibody reactivity, all three components of the Ag85 complex induced significant lymphoproliferation and IFN-γ production in PBMC from healthy tuberculin reactors. These results suggest that the cross-reactive epitopes recognized by T cells are present in these proteins. In mapping of the T-cell epitopes analyzed by different workers (13, 20), there was only partial correlation between the epitopes of 85A and 85B in healthy tuberculin reactors. Others found that a few peptides of the two antigens were identical (14). However, because highly diverse epitopes of this complex may be processed and presented in vivo, it is possible that there are no significant differences among the three proteins. In addition, mean proliferative responses to 85B and 85A were relatively higher than that to 85C in PBMC from healthy tuberculin reactors. One recent report (14) indicated that the level of lymphocyte proliferation in response to the 30-kDa protein allows more discrimination between immunized and control animals than that in response to the 32-kDa protein. Our findings and the above-mentioned reports show that highly immunogenic or component-specific epitopes are present in the Ag85 complex.

Recently, DNA vaccination with the genes encoding the 85A and 85B (but not 85C) components of the Ag85 complex resulted in a strong stimulation of a specific Th1-like response and of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity in animal models (15). Therefore, further detailed comparison of cellular immune responses to 85B, 85A, and 85C will provide fundamental knowledge of the immunological parameters which correlate with protective immunity against TB in humans.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Korea (HMP-98-B-1-003) and in part by the Korea Research Foundation (1998-003-F00067).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bentley-Hibbert S I, Quan X, Newman T, Huygen K, Godfrey H P. Pathophysiology of antigen 85 in patients with active tuberculosis: antigen 85 circulates as complexes with fibronectin and immunoglobulin G. Infect Immun. 1999;67:581–588. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.581-588.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Content J, de la Cuvellerie A, de Wit L, Vincent-Levy-Frebault V, Ooms J, De Bruyn J. The genes coding for the antigen 85 complexes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis BCG are members of a gene family: cloning, sequence determination, and genomic organization of the gene coding for antigen 85-C of M. tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3205–3212. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3205-3212.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Bruyn J, Huygen K, Bosmans R, Fauville M, Lippens R, Van Vooren J P, Falmagne P, Weckx M, Wiker H G, Harboe M, Turneer M. Purification, characterization and identification of a 32 kDa protein antigen of Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Microb Pathog. 1987;2:351–366. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garbe T R, Hibler N S, Deretic V. Isoniazid induces expression of the antigen 85 complex in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1754–1756. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.7.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harth G, Lee B Y, Wang J, Clemens D L, Horwitz M A. Novel insights into the genetics, biochemistry, and immunocytochemistry of the 30-kilodalton major extracellular protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3038–3047. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3038-3047.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Havlir D V, Wallis R S, Boom W H, Daniel T M, Chervenak K, Ellner J J. Human immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens. Infect Immun. 1991;59:665–670. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.2.665-670.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horwitz M A, Lee B W E, Dillon B J, Harth G. Protective immunity against tuberculosis induced by vaccination with major extracellular proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1530–1534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huygen K, Van Vooren J P, Turneer M, Bosmans R, Dierckx P, De Bruyn J. Specific lymphoproliferation, gamma interferon production, and serum immunoglobulin G directed against a purified 32 kDa mycobacterial protein antigen (P32) in patients with active tuberculosis. Scand J Immunol. 1988;27:187–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1988.tb02338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan M H, Chase M W. Antibodies to mycobacteria in human tuberculosis. I. Development of antibodies before and after antimicrobial therapy. J Infect Dis. 1980;142:825–834. doi: 10.1093/infdis/142.6.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim H J, Jo E K, Park J K, Lim J H, Min D, Paik T H. Isolation and partial characterisation of the Triton X-100 solubilised protein antigen from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Med Microbiol. 1999;48:585–591. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-6-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim S K, Paik T H, Kim H J, Park J K, Choi T K. Purification and immunochemical characterization of α-antigen from the culture filtrate of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Korean Soc Microbiol. 1991;26:45–60. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Launois P, DeLeys R, Niang M N, Drowart A, Andrien M, Dierckx P, Cartel J-L, Sarthou J-L, Van Vooren J-P, Huygen K. T-cell-epitope mapping of the major secreted mycobacterial antigen Ag85A in tuberculosis and leprosy. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3679–3687. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3679-3687.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee B Y, Horwitz M A. T-cell epitope mapping of the three most abundant extracellular proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in outbred guinea pigs. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2665–2670. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2665-2670.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lozes E, Huygen K, Content J, Denis O, Montgomery D L, Yawman A M, Vandenbussche P, Van Vooren J P, Drowart A, Ulmer J B, Liu M A. Immunogenicity and efficacy of a tuberculosis DNA vaccine encoding the components of secreted antigen 85 complex. Vaccine. 1997;15:830–833. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyashchenko K, Colangeli R, Houde M, Jahdali H A, Menzies D, Gennaro M L. Heterogenous antibody responses in tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3936–3940. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3936-3940.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagai S, Wiker H G, Harboe M, Kinomoto M. Isolation and partial characterization of major protein antigens in the culture fluid of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:372–382. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.1.372-382.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pessolani M C V, Peralta J M, Rumjanek F D, Gomes H M, de Melo Marques M A, Almeida E C C, Saad M H F, Sarno E N. Serology and leprosy: immunoassays comparing immunoglobulin G antibody responses to 28- and 30-kilodalton proteins purified from Mycobacterium bovis BCG. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2285–2290. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.10.2285-2290.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoel B, Gulle H, Kaufmann S H E. Heterogeneity of the repertoire of T cells of tuberculosis patients and healthy contacts to Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens separated by high-resolution techniques. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1717–1720. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1717-1720.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silver R F, Wallis R S, Ellner J J. Mapping of T cell epitopes of the 30-kDa α antigen of Mycobacterium bovis strain bacillus Calmette-Guerin in purified protein derivative (PPD)-positive individuals. J Immunol. 1995;154:4665–4674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torres M, Herresa T, Villareal H, Rich E A, Sada E. Cytokine profiles for peripheral blood lymphocytes from patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis and healthy household contacts in response to the 30-kilodalton antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:176–180. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.176-180.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turneer M, Van Vooren J P, De Bruyn J, Serruys E, Dierckx P, Yernault J C. Humoral immune response in human tuberculosis: immunoglobulins G, A, and M directed against the purified P32 protein antigen of Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guerin. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1714–1719. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.9.1714-1719.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Vooren J P, Drowart A, De Bruyn J, Launois P, Millan J, Delaporte E, Develoux M, Yernault J C, Huygen K. Humoral responses against the 85A and 85B antigens of Mycobacterium bovis BCG in patients with leprosy and tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1608–1610. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.6.1608-1610.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Vooren J P, Drowart A, Van Onckelen A, Hoop M H, Yernault J C, Valcke C, Huygen K. Humoral immune response of tuberculous patients against the three components of the Mycobacterium bovis BCG 85 complex separated by isoelectric focusing. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2348–2350. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.10.2348-2350.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiker H G, Harboe M. The antigen 85 complex: a major secretion product of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:648–661. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.4.648-661.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiker H G, Harboe M, Lea T E. Purification and characterization of two protein antigens from the heterogenous BCG85 complex in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1986;81:298–306. doi: 10.1159/000234153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiker H G, Harboe M, Nagai S, Bennedsen J. Quantitative and qualitative studies on the major extracellular antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv and Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:830–838. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.4_Pt_1.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]