Abstract

Background:

Neuraxial anesthesia in obstetrics began with the spinal block by Oskar Kreis in 1900. The technique of subarachnoid blockade has been refined since then and various drugs have been used to provide analgesia and anesthesia for infraumbilical surgeries.

Materials and Methods:

This study was conducted because of newer options available, such as an intrathecal drug with appropriate sensory and motor blockade and minimal haemodynamic changes that can be used in the lower segment cesarean section safely. Ninety patients were randomly divided into three groups including 30 patients in each group. Group B, Group L, and Group R, each receiving 2.2 mL of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine, 0.5% isobaric levobupivacaine, and 0.5% isobaric ropivacaine, respectively. All groups were compared concerning sensory block, motor block, hemodynamic stability, and complications if any.

Results:

The onset of sensory block at T8, two-segment regression time from the highest block, time of regression to L1, total duration of analgesia, onset and total duration of motor block were comparable between Group B and L (P > 0.05), but both these groups were statistically significant with Group R (P < 0.05). Hypotension was observed among all the groups; however, the incidence was minimum in Group R.

Conclusion:

12 mg of isobaric ropivacaine and 12 mg of isobaric levobupivacaine, compared to 12 mg hyperbaric bupivacaine (2.2 mL of 0.5% each), when administered intrathecally provides adequate anesthesia for cesarean section. The lesser duration of motor block in ropivacaine compared to the other two drugs could be beneficial for early ambulation, also the incidence of hypotension was lower in Group R.

Keywords: Bupivacaine, cesarean section, levobupivacaine, ropivacaine, subarachnoid block

INTRODUCTION

Neuraxial anesthesia in obstetrics began with the spinal block using cocaine by Oskar Kreis in July 1900 and the spectrum of spinal drugs has widened since then.

One of the most important properties of long-acting local anesthetics is to reversibly inhibit the nerve impulse, thus causing a prolonged sensory and motor blockade appropriate for anaesthesia in different types of surgeries. The acute pain relief obtained at lower doses in postoperative and labor patients due to sensory blockade is sometimes marred by accompanying motor blockade, which serves no purpose and is quite undesirable.

Hyperbaric bupivacaine (0.5%), an amide-type of local anesthetic, has been the gold standard for intrathecal use in spinal anesthesia for many years but also has been associated with severe hypotension, delayed recovery of motor block, and also cardiotoxicity when used in large concentration or when accidentally administered intravascularly.[1] The introduction of ropivacaine and levobupivacaine with a better margin of safety for local anesthetic systemic toxicity is preferred for continuous infusions and large volume regional blocks.[2,3,4] Various studies have evaluated the effectiveness of these newer drugs for spinal anesthesia using hyperbaric and isobaric solutions with a reliable rate of success.[5,6,7]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a prospective study conducted in our institution after Institutional Ethics committee (No: 92 IEC, RIMS, Ranchi dated 16/02/2019). This study adhered with CONSORT statement, as shown in Figure 1.[8] The research followed the guidelines laid down by Declaration of Helsinki (2013). A written informed consent was obtained for participation in the study and use of patient data for research and educational purposes. Our study aimed to compare the efficacy of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine, 2.2 mL with 0.5% isobaric levobupivacaine, 2.2 mL and 0.5% isobaric ropivacaine, 2.2 mL in spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery in terms of sensory, motor block characteristics, intra-operative hemodynamics stability, and side effects.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram

Written informed consent was obtained from 90 pregnant women of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) PS classes I and II, in the age group between 18 and 35 years with singleton pregnancy and term gestation undergoing intrathecal anesthesia for cesarean section in labour OT, were randomized into three groups of 30 patients each, using “closed envelope method.” The drugs used were shielded for identity by opaque paper a third party agency from our hospital and the anesthesiologist, patient, and data collection team were unaware about the drug.

The exclusion criteria included lack of consent, patients with contraindication to spinal anaesthesia, presence of comorbidities, and patients belonging to ASA PS classes >III. Patients in: Group B (n = 30 patients):intrathecal inj. 0.5%hyperbaric bupivacaine (2.2 mL) Group L (n = 30 patients): Intrathecal inj. 0.5% isobaric levobupivacaine (2.2 mL) Group R (n = 30 patients): Intrathecal inj. 0.5% isobaric ropivacaine (2.2 mL).

On arrival in the operating room, each patient was identified and then placed on a tilting operating table, multipara monitor including basal heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), noninvasive blood pressure, and peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) were attached. Before commencement of anesthesia, patients were instructed about the method of sensory and motor assessments, under all aseptic precautions spinal block, was performed with the patient in lateral decubitus position, the subarachnoid space was entered at the L2–L3, L3–L4, or L4–L5 interspace through midline approach using 25G Quinck's spinal needle, the space was confirmed by ensuring the free flow of cerebrospinal fluid from the needle and according to their randomization, the patient received an intrathecal injection of either 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine (12 mg) or 0.5% isobaric ropivacaine (12 mg) or 0.5% isobaric levobupivacaine (12 mg).

After the completion of the spinal injection, the patients were placed in a supine position immediately. Patient vital parameters plus sensory and motor block were recorded every 1 min for the first 15 min and then every 5 min till 60 min, every 10 min till 90 min and then at the end of the 2nd h, 6th h, 12th h, and 24 h. Clinically, relevant bradycardia was defined as a decrease in HR of 5.min-1 and was treated with 0.6 mg atropine iv as needed. The occurrence of hypotension (decline in MAP <20% from baseline, systolic blood pressure [SBP] <90 mmHg or MAP <50 mmHg) was noted during surgery and was treated with 6 mg mephentermine intravenous (i.v.) bolus and an additional i.v/fluid bolus (Ringer's lactate 5 mL.kg−1 over 5 min). For nausea and vomiting, i.v., ondansetron 4 mg was given. All data collection was recorded on a pro forma. After the completion of surgery, patients were monitored for regression of motor and sensory blocks. The patients were asked to request analgesia drugs when they felt unbearable pain. Patients with failed blocks or inadequate or incomplete blocks were excluded from the study.

The effectiveness of the sensory block was assessed using pain sensation by pricking with a hypodermic needle and the motor block was assessed using the Bromage scale (B0 = no motor loss, B1 = inability to flex the hip, B2 = inability to flex the knee, and B3 = inability to flex the ankle).

Statistical method

Before the study was carried out, a power analysis indicated that 23 patients per group would be required to detect a 10% difference in hemodynamic parameters. The α error was set at 0.05 and the β error at 0.9. Thus, sample size of n = 30 per group was considered for our study. All qualitative data were analyzed using the Chi-square test and quantitative data using the Student's t-test. All data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. P > 0.05 was regarded as nonsignificant, P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant and P < 0.01 was taken as highly significant.

RESULTS

The demographic profile is compared in all 3 groups, shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic profile (n=30)

| Group B | Group L | Group R | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 25.13±4.25 | 26.53±4.55 | 24.23±4.25 |

| Weight (kg) | 62.5±4.17 | 62.13±4.57 | 63.4±4.02 |

| Height (cm) | 156.57±4.35 | 158.47±5.10 | 157.93±4.14 |

| ASA classification | 1.46±0.50 | 1.43±0.50 | 1.43±0.50 |

ASA=American Society of Anaesthesiologists

The sensory block characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sensory block

| Parameters | Group B | Group L | Group R |

P

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group B versus L | Group B versus R | Group L versus R | ||||

| Onset of sensory blockade at T8 (min) | 2.30±0.48 | 2.35±33.91 | 3.02±0.48 | 0.732 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| Highest sensory level achieved (level of spinal segment) | 4.4±0.621 | 5.2±0.76 | 5.33±0.60 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.456 |

| Two segment regression time from highest block (min) | 104±10.77 | 96.67±18.30 | 90.83±9.01 | 0.06 | 0.0001 | 0.0046 |

| Time of regression to L1 (min) | 162.67±12.78 | 153.33±23.68 | 108.33±12.01 | 0.845 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| Total duration of analgesia (min) | 138.17±10.46 | 137.67±16.95 | 126.67±15.55 | 0.89 | 0.0001 | 0.01 |

Motor block characteristics are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Motor block characteristics

| Parameters | Group B | Group L | Group R |

P

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group B versus L | Group B versus R | Group L versus R | ||||

| Onset of motor block to B1 | 1.88±0.23 | 1.97±1.51 | 2.26±0.29 | 0.098 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| Onset of motor block to B3 | 7.17±1.70 | 8.16±2.50 | 10.83±2.82 | 0.078 | 0.0001 | 0.0003 |

| Total duration of motor block | 146.33±16.45 | 141±18.07 | 113±15.12 | 0.237 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

B1=Inability to flex the hip, B3=Inability to flex the ankle

Spinal anesthesia was accomplished in all the patients. Overall sensory and motor block characteristics were comparable between Group B and Group L but significant with Group R, however, the highest level of sensory block achieved was comparable between Group L and Group R but highly significant with Group B. Mean duration of request for analgesia was 152.17 ± 10.64 min for Group B, 133.67 ± 20.08 min for Group L, 103.33 ± 13.48 min for the group, Group B and Group L were comparable; however, both the groups were statistically significant with Group R. Visual Analog Score during the postoperative period in 2 h was clinically and statistically significant between Group B and Group R, also between Group L and Group R (P < 0.05); however, during postoperative in 6 h, 12 h, 24 h was comparable among the three groups (P > 0.05). Hemodynamic parameters HR, SBP, diastolic blood pressure, SpO2, and RR were statistically comparable at various points of time between the groups.

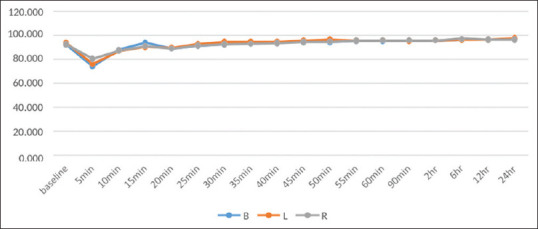

There was a significant fall in mean arterial pressure (P < 0.05) was found between Group B and Group R at 5 min, Group B and Group L, at 15 min, and Group B and Group R at 15 min, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of mean arterial pressure

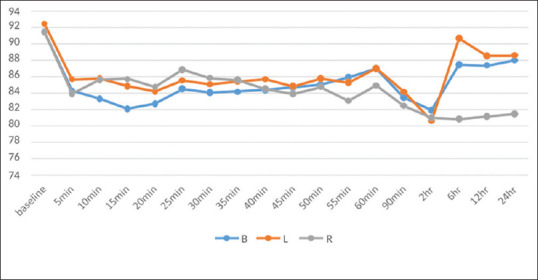

No statistically significant difference was seen in the between group or within-group comparison of HR, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of heart rate at various time interval

There was a significant fall in mean arterial pressure (P < 0.05) was found between Group B and Group R at 5 min, Group B and Group L, at 15 min, and Group B and Group R at 15 min.

Hypotension was seen in all the three groups, comparable between Group B and Group L, Group L and Group R; however, statistically significant between Group B and Group R. Two babies in group B, one baby in each group L and group R was needed resuscitation in 1 min, but overall mean APGAR score was comparable at 1 min and 5 min in various groups. Hypotension and other complications have been shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Side effects and complications

| Events | Group B, n (%) | Group L, n (%) | Group R, n (%) |

P

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group B versus L | Group B versus R | Group L versus R | ||||

| Hypotension | 20 (66.66) | 15 (50) | 10 (33.33) | 0.196 | 0.009 | 0.196 |

| Bradycardia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea vomiting | 7 (23.33) | 5 (16.66) | 3 (10) | 0.526 | 0.171 | 0.456 |

| Pruritus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shivering | 5 (16.66) | 2 (6.66) | 2 (6.66) | 0.234 | 0.234 | 1 |

| Neurological complication | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other complication | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

DISCUSSION

The drug most often used in spinal anesthesia is bupivacaine in 8% glucose. Bupivacaine is available as a racemic mixture of its enantiomers, dextrobupivacaine and levobupivacaine.[8] In the last few years, its pure S-enantiomers, ropivacaine and levobupivacaine, have been introduced into clinical practice because of their lower toxic effects on the heart and central nervous system (CNS).[9,10,11,12] The physicochemical properties of the two enantiomeric molecules are identical, but the two enantiomers can have substantially different behaviors in their affinity for either the site of action or the sites involved in the generation of side effects. R(+) and S(−) enantiomers of local anesthetics have been demonstrated to have different affinities for different ion channels of sodium, potassium, and calcium; this results in a significant reduction in the CNS and cardiac toxicity of the S(−) enantiomer as compared with bupivacaine. We used12.5 mg of isobaric ropivacaine (2.2 mL of 0.5%) in our present study based on the rationale that the duration of action of ropivacaine in SA is approximately 50%–67% that of bupivacaine.[13] Moreover, all our patients were term parturient; hence, the volume of the drug played a major role in the cephalad spread of the drug and the height of the block.[14] The above dosages were found to be adequate for elective cesarean section and the surgery was completed successfully with no maternal or neonatal adverse effects.

All patients receiving either drug achieved an adequate level of anesthesia. In our study, the sensory block at T8 was earliest in the bupivacaine group and delayed in the ropivacaine group.

Sethi in their study used 10 mg bupivacaine, 10 mg levobupivacaine, 15 mg ropivacaine and also noted that the time of onset of sensory block at T8 was delayed in the ropivacaine group and earlier in the bupivacaine group.[15]

In our study, 66.66% of patients, receiving hyperbaric bupivacaine achieved T4 level as the highest sensory block, in the isobaric levobupivacaine group, 20% has achieved T4 level and only 6.66% of patients in the isobaric ropivacaine group achieved T4 level as the highest level of sensory block.

Solakovic in their study on “ Level of sensory block and baricity of bupivacaine 0.5% in spinal anaesthesia” concluded that in the hyperbaric group the highest recorded level of the block was the first thoracic segment-T1 (3.33%) and the lowest level was seventh thoracic segment T7 (6.66%). In the isobaric group, the highest recorded level was T5 (3.33%) and the lowest was L2 (3.33%).[16] Two segment regression from highest sensory block. In our study, two-segment regression time was 104.83 ± 10.77 and 96.67 ± 18.30 for hyperbaric bupivacaine and isobaric levobupivacaine, respectively, which was statistically not significant. However, the meantime of two-segment regression from the highest sensory block is lesser in levobupivacaine than bupivacaine Devi in their study on comparison of isobaric levobupivacaine (2.5 mL of 0.5%) and hyperbaric bupivacaine (2.5 mL of 0.5%) in spinal anesthesia in endourology found that the mean two-segment regression time in Group L was 88.140 ± 6.395 min while in Group B was 101.22 ± 8.21 min, the P value was 0.001 which is statistically significant.[17]

However, in another study by Sethi in 2019, randomized control trial comparing plain 0.5% Levobupivacaine (10 mg) and 0.75% Ropivacaine (15 mg) with 0.5% Hyperbaric Bupivacaine (10 mg) in cesarean deliveries concluded that sensory two segment regression time for 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine group was 102.18 ± 29.12, and for 0.5% isobaric levobupivacaine was 91.40 ± 33.94, which was statistically not significant.[15]

In the same study by Sethi, time of two-segment regression from the highest sensory block for 0.75% ropivacaine (15 mg) was 95.80 ± 21.45 min, which was lesser than another group of drugs, i.e., bupivacaine and levobupivacaine, this corresponds to our study where ropivacaine has 90.83 ± 9.0 min as mean two-segment regression time, which is lesser than levobupivacaine and bupivacaine.

Boztuğ et al. noted that the time of regression of block to L1 was faster with ropivacaine (116 ± 31 min in ropivacaine group v/s 152 ± 64.5 min in bupivacaine group) when used for outpatient arthroscopic surgeries.[18]

We also observed that regression to L1 with ropivacaine was earlier compared to bupivacaine.

In our study, total duration of analgesia at S1 for bupivacaine was prolonged (i. e-138 ± 10.46) than ropivacaine (i.e., 126.67 ± 15.55), which was statistically highly significant.

Chung et al. in their study also noted that the total duration of analgesia was longer (188.56 ± 28.2) min in the bupivacaine group when compared to the ropivacaine group (162.56 ± 20.2) min.[19]

Devi in their study on comparison of levobupivacaine and bupivacaine in Spinal Anesthesia in Endourology found that the duration of sensory blockade was shorter in the Levobupivacaine group, this correlated to our study; however, Glaser et al.[17,20] reported a similar duration of sensory blockade between Levobupivacaine and Bupivacaine in spinal anesthesia for elective hip replacement surgeries. This does not correlate with our study.

In our study, mean time to achieve the maximum motor block of Bromage grade 3 was 7.17 ± 1.70, 8.16 ± 0.50, 10.8 ± 2.82 min for bupivacaine, levobupivacaine, and ropivacaine, respectively.

This correlated with the study done by P. Gautier et al. where they compared the effects of intrathecal bupivacaine (8 mg), levobupivacaine (8 mg), ropivacaine (12 mg), for cesarean section and found that the meantime of onset of grade 3 Bromage motor block was 9 min, 13 min, and 14 min for bupivacaine, levobupivacaine, and ropivacaine, respectively.[21]

We observed a shorter duration of the motor block with ropivacaine (113 ± 15.12 min) when compared to bupivacaine (146.33 min) and levobupivacaine (141.18.07 min), as shown in Table 3. These findings are in affirmation with that of a similar study done by Chung et al.[19]

Malhotra et al. also concluded that intrathecal ropivacaine resulted in a reduced duration of motor block, regressing 35.7 min earlier compared with intrathecal bupivacaine (P < 0.00001).[22]

Mean APGAR score at 1 mine was 9.43 ± 1.40 for bupivacaine, 9.76 ± 0.43 for levobupivacaine and 9.73 ± 0.44 for ropivacaine, at 5 min 9.83 ± 0.37 for bupivacaine, 9.73 ± 0.52 for levobupivacaine and 9.8 ± 0.406 for ropivacaine.

We observed that hypotension and nausea vomiting were the least common in-group ropivacaine than group levobupivacaine and maximum in bupivacaine.

In our study, 66.6% of patients of the group developed hypotension, 50% in levobupivacaine and 33.33% in ropivacaine.

Whiteside et al., while comparing hyperbaric ropivacaine 0.5% with hyperbaric bupivacaine 0.5% used for spinal anesthesia for elective surgery, found a significantly lower incidence of hypotension with ropivacaine, as seen in our study 33.33% of patients in the ropivacaine group developed hypotension, whereas 66.66% and 50% of patients in bupivacaine and mepivacaine, respectively, developed hypotension.[23]

The incidence of nausea and vomiting was comparable between groups in our study. Urinary retention could not be observed as all the patients were catheterized for 24 h. Shivering was comparable in both the groups and no other complications such as respiratory depression, pruritus, headache, and neurological complications were observed in any patients of all three groups.

CONCLUSION

Our study reveals that 12 mg of isobaric ropivacaine (2.2 mL of 0.5%) and 12 mg of isobaric levobupivacaine (2.2 mL of 0.5%), compared to 12 mg hyperbaric bupivacaine (2.2 mL of 0.5%), when administered intrathecally provides adequate anesthesia for cesarean section. The onset of sensory block was comparable between bupivacaine and levobupivacaine but delayed in the ropivacaine group. The highest level of sensory block was higher in hyperbaric bupivacaine than isobaric levobupivacaine and ropivacaine, also regression of sensory blockade was significantly earlier in the ropivacaine group, followed by levobupivacaine and bupivacaine. There was a delayed onset of motor block in the ropivacaine group than the bupivacaine and levobupivacaine group, but a shorter duration of motor block was seen in the ropivacaine group. Although hypotension was observed among all three groups, the incidence was minimum in ropivacaine. Hence, both ropivacaine and levobupivacaine can be used successfully for the cesarean section where early recovery and early maternal-infant bonding, as well as successful breastfeeding, is well appreciated by the mother. No depressant effect on the neonate was seen with intrathecal bupivacaine, levobupivacaine, or ropivacaine.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hansen TG. Ropivacaine: A pharmacological review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2004;4:781–91. doi: 10.1586/14737175.4.5.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster RH, Markham A. Levobupivacaine: A review of its pharmacology and use as a local anaesthetic. Drugs. 2000;59:551–79. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059030-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goel S, Bhardwaj N, Grover VK. Intrathecal fentanyl added to intrathecal bupivacaine for day case surgery: A randomized study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2003;20:294–7. doi: 10.1017/s0265021503000462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van de Velde M. There is no place in modern obstetrics for racemic bupivacaine. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2006;15:38–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erdil F, Bulut S, Demirbilek S, Gedik E, Gulhas N, Ersoy MO. The effects of intrathecal levobupivacaine and bupivacaine in the elderly. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:942–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.05995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hakan Erbay R, Ermumcu O, Hanci V, Atalay H. A comparison of spinal anesthesia with low-dose hyperbaric levobupivacaine and hyperbaric bupivacaine for transurethral surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Minerva Anestesiol. 2010;76:992–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alley EA, Kopacz DJ, McDonald SB, Liu SS. Hyperbaric spinal levobupivacaine: A comparison to racemic bupivacaine in volunteers. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:188–93. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200201000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: Revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:657–62. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanna O, Chumsang L, Thongmee S. Levobupivacaine and bupivacaine in spinal anesthesia for transurethral endoscopic surgery. J Med Assoc Thai. 2006;89:1133–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markham A, Faulds D. Ropivacaine. A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic use in regional anaesthesia. Drugs. 1996;52:429–49. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199652030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McClellan KJ, Spencer CM. Levobupivacaine. Drugs. 1998;56:355–62. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199856030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milligan KR. Recent advances in local anaesthetics for spinal anaesthesia. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2004;21:837–47. doi: 10.1017/s0265021504000158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kallio H, Snäll EV, Suvanto SJ, Tuomas CA, Iivonen MK, Pokki JP, et al. Spinal hyperbaric ropivacaine-fentanyl for day-surgery. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hocking G, Wildsmith JA. Intrathecal drug spread. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93:568–78. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sethi D. Randomised control trial comparing plain levobupivacaine and ropivacaine with hyperbaric bupivacaine in caesarean deliveries. Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim. 2019;47:471–9. doi: 10.5152/TJAR.2019.50465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solakovic N. Level of sensory block and baricity of bupivacaine 0.5% in spinal anesthesia. Med Arh. 2010;64:158–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devi R. Comparison of levobupivacaine and bupivacaine in spinal anaesthesia in endourology: A study of 100 cases. Int J Anesth Pain Med. 2020;6:28. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boztuğ N, Bigat Z, Karsli B, Saykal N, Ertok E. Comparison of ropivacaine and bupivacaine for intrathecal anesthesia during outpatient arthroscopic surgery. J Clin Anesth. 2006;18:521–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung CJ, Choi SR, Yeo KH, Park HS, Lee SI, Chin YJ. Hyperbaric spinal ropivacaine for cesarean delivery: A comparison to hyperbaric bupivacaine. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:157–61. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200107000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glaser C, Marhofer P, Zimpfer G, Heinz MT, Sitzwohl C, Kapral S, et al. Levobupivacaine versus racemic bupivacaine for spinal anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:194–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200201000-00037. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gautier P, De Kock M, Huberty L, Demir T, Izydorczic M, Vanderick B. Comparison of the effects of intrathecal ropivacaine, levobupivacaine, and bupivacaine for Caesarean section. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91:684–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malhotra R, Johnstone C, Halpern S, Hunter J, Banerjee A. Duration of motor block with intrathecal ropivacaine versus bupivacaine for caesarean section: A meta-analysis. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2016;27:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whiteside JB, Burke D, Wildsmith JA. Comparison of ropivacaine 0.5% (in glucose 5%) with bupivacaine 0.5% (in glucose 8%) for spinal anaesthesia for elective surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2003;90:304–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]