Abstract

Background

Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DHA-PPQ) combination therapy is the current first-line treatment for Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Thailand. Since its introduction in 2015, resistance to this drug combination has emerged in the eastern part of the Greater Mekong Subregion including the eastern part of Thailand near Cambodia. This study aimed to assess whether the resistance genotypes have arisen the western part of country.

Methods

Fifty-seven P. falciparum-infected blood samples were collected in Tak province of northwestern Thailand between 2013 and 2019. Resistance to DHA was examined through the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of kelch13. PPQ resistance was examined through the copy number plasmepsin-2 and the SNPs of Pfcrt.

Results

Among the samples whose kelch13 were successfully sequenced, approximately half (31/55; 56%) had mutation associated with artemisinin resistance, including G533S (23/55; 42%), C580Y (6/55; 11%), and G538V (2/55; 4%). During the study period, G533S mutation appeared and increased from 20% (4/20) in 2014 to 100% (9/9) in 2019. No plasmepsin-2 gene amplification was observed, but one sample (1/54) had the Pfcrt F145I mutation previously implicated in PPQ resistance.

Conclusions

Kelch13 mutation was common in Tak Province in 2013–2019. A new mutation G533S emerged in 2014 and rose to dominance in 2019. PPQ resistance marker Pfcrt F145I was also detected in 2019. Continued surveillance of treatment efficacy and drug resistance markers is warranted.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12936-022-04382-5.

Keywords: DHA-PPQ, Plasmodium falciparum, kelch13, Pfcrt, plasmepsin-2

Background

Malaria is a vector-borne parasitic disease threatening the health of several billions of people in the endemic areas of tropical and subtropical regions. Based on the data of 2020, 241 million people suffered from malaria in 85 malaria-endemic countries and approximately 627,000 people died from the disease worldwide [1]. The burden of malaria increased in 2020 due to the service disruption during the COVID19 pandemic. Of the 241 million cases, approximately 2% were from the Southeast Asian region, whose 60% of clinical malaria cases were due to Plasmodium falciparum [1].

Artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) was the first-line treatment for uncomplicated falciparum malaria in most malaria-endemic areas. Clinical artemisinin resistance was first identified in western Cambodia in 2008 and has spread to other countries in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) [2–4]. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the propeller domain of the P. falciparum kelch13 gene were found to confer artemisinin resistance [5]. These SNPs are widely used to monitor the emergence and spread of artemisinin resistance [5]. According to a recent systematic review, a total of 165 non-synonymous SNPs on kelch13 have been reported globally [6]. Of these non-synonymous SNPs, 84 were from South-East Asia [6]. Among the mutations that have been associated with artemisinin resistance, C580Y, R539T, Y493H, and I543T mutations were common in Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos, whereas the F446I, N458Y, P574L, and R561H mutations dominated in the western part of Thailand, Myanmar, and China [7].

In 2015, the dihydroartemisinin (DHA)-piperaquine (PPQ) combination replaced artemisinin-mefloquine as the first-line treatment for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in Thailand [8]. As a result of a rapid rise of artemisinin resistance in Cambodia, hence a strong pressure on its partner drug, there was substantial growth in the failure rate of DHA-PPQ treatment reaching up to 60% in some areas of Cambodia [9–11]. Amplification of P. falciparum plasmepsin-2 and 3 genes on chromosome 14 was associated with PPQ resistance in Cambodian isolates [9, 12]. This marker has since been adopted as a molecular marker of PPQ resistance [13–15]. Recent studies also reported that mutations in P. falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter (Pfcrt) gene at nucleotide positions downstream of the 4-aminoquinoline resistance locus (amino acids 72–76), particularly at codons T93S, H97Y, F145I may also contribute to PPQ resistance [13, 16, 17].

Reports of DHA-PPQ treatment resistance have come mainly from the eastern GMS, but the therapeutic efficacy of DHA-PPQ was still high in Myanmar [18]. Thus, it is crucial to monitor DHA-PPQ resistance in the western part of Thailand, as it is the gateway to Myanmar, Bangladesh and India. It was hypothesized that the frequency of DHA-PPQ resistance may have risen in this area after the introduction of DHA-PPQ in 2015. To test this hypothesis, the molecular markers of P. falciparum DHA-PPQ resistance were determined in Tak province of northwestern Thailand, using specimens collected during 2013–2019. The resistance markers included a selection of well-supported SNPs on kelch13 for artemisinin resistance and plasmepsin-2 amplification and SNPs on Pfcrt for PPQ resistance.

Methods

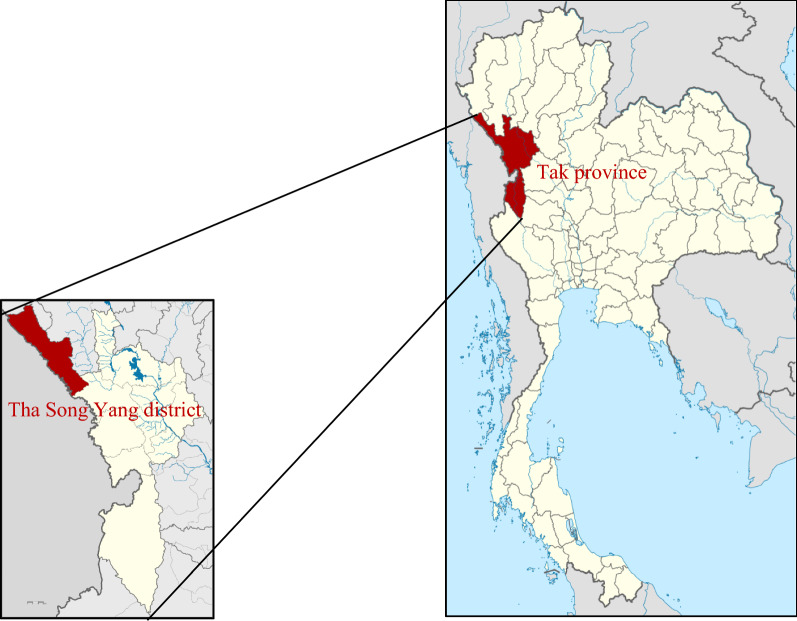

This is a retrospective analysis of molecular markers of artemisinin and PPQ resistance in 57 P. falciparum specimens. The parasites were collected as dry blood spots (DBS) or frozen whole blood between 2013 and 2019 from Tha Song Yang district of Tak Province (Fig. 1) in northwestern Thailand.

Fig. 1.

Map showing Tha Song Yang district, Tak province, Thailand [32, 33]

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA of P. falciparum-infected blood was extracted from DBS or frozen whole blood samples using QIAamp DNA Mini Kit or Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Determining kelch13 mutations

Nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out according to the K13 Artemisinin Resistance Multicenter Assessment (KARMA) standard operating procedure [7]. The primary and secondary forward and reverse primers can be found in Additional file 1: Table S1 [7]. Sequencing was carried out using the commercial dye-terminator method and the sequences were aligned against the 3D7 reference strain to detect mutations in the propeller domain between codons 442 and 687.

Determining plasmepsin-2 copy number

The copy number of the plasmepsin-2 gene per genome was determined by SYBR Green quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Additional file 1: Table S2). Plasmodium falciparum ꞵ-tubulin, a single copy gene, was used as the reference for copy number quantification. The primer sequences for both plasmepsin-2 and ꞵ-tubulin qPCR (Additional file 1: Table S1) were from Witkowski et al. [9]. The copy number of plasmepsin-2 was estimated as 2−dCt where dCt was the deviation of Ct,plasmepsin-2 from the plasmepsin-2/β-tubulin trendline constructed from serial dilution of cultured 3D7, which has a single copy of plasmepsin-2 per genome. A copy number value of 1.5 or higher was considered multicopy. All qPCRs were performed in duplicates. P. falciparum parasite isolates obtained from northeastern Thailand, where multicopy plasmepsin-2 was common, were used to provide a reference for comparison.

Determining Pfcrt mutations

Primers (Additional file 1: Table S1) were used to amplify gene fragments containing the T93S and H97Y locus in exon 2, and the F145I locus in exon 3. Pfcrt exon 2 and exon 3 amplification was carried out according to the PCR conditions in Additional file 1: Table S3. Sequencing was performed using the commercial dye-terminator method and the results were aligned against the 3D7 reference sequence to detect mutations.

Data analysis

The histogram was prepared using Microsoft Excel. Fisher’s exact test (SPSS version 18) was used to compare the proportions of G533S between 2014–2015 and 2018–2019.

Results

G533S mutation of kelch13 emerged and became the dominant genotype in Tak Province

Fifty-seven P. falciparum specimens were collected from Tha Song Yang district, Tak province (Fig. 1) during 2013–2019. Of these, 55 were successfully amplified and sequenced. Mutations were observed in 31 samples (56%). The most common mutation was G533S (23/55; 42%) which has been shown to reduce in vitro artemisinin sensitivity in a previous study [19]. G533S was first detected in 2014 (Table 1), but by 2019, all isolates had this mutation. Comparing years 2014–2015 to 2018–2019, the proportions of parasites with G533S increased from 30% (11/37) to 80% (12/15) (p = 0.002, Fisher’s exact test). Two additional resistance-associated mutations C580Y (6/55, 11%) and G538V (2/55; 4%) were found, but no other major mutations (P441L, F446I, G449A, N458Y, C469F, M476I, A481V, Y493H, P527H, N537I, R539T, I543T, P553L, R561H, V568G, P574L, F673I, A675V) were detected. One isolate had the R659R synonymous SNP and one had both G533S and A564A.

Table 1.

Non-synonymous SNPs in kelch13 found in Tha Song Yang district, Tak province, Thailand

| SNPs | 2013 (n = 2) |

2014 (n = 20) |

2015 (n = 17) |

2016 (n = 1) |

2017 (n = 0) |

2018 (n = 6) |

2019 (n = 9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G533Sa | 0 | 4 (20%) | 7 (41%) | 0 | 0 | 3 (50%) | 9 (100%) |

| C580Yb | 2 (100%) | 2 (10%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (33.3%) | 0 |

| G538Vc | 0 | 1 (5%) | 1 (5.9%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

aAssociated with in vitro artemisinin resistance in Zhang’s study [19]

bValidated as artemisinin resistance

cAssociated with artemisinin resistance

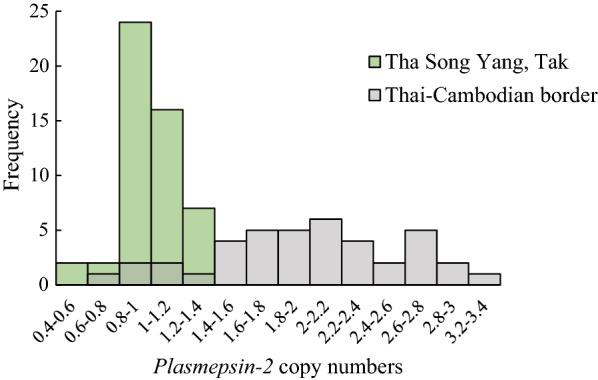

No evident marker of PPQ resistance was found

Two markers of PPQ resistance were examined, plasmepsin-2 amplification and Pfcrt mutations (T93S, H97Y, and F145I). Fifty-one isolates were successfully analysed for the plasmepsin-2 copy number, but none had multicopy plasmepsin-2 (Fig. 2). Fifty-two isolates were successfully sequenced at the Pfcrt T93S and H97Y locus, and neither mutation was found. Of the 54 isolates successfully sequenced at the F145I locus, one had this mutation. This parasite was collected in 2019 and also had the G533S mutation. The complete genotyping results can be found in Table 2.

Fig. 2.

The plasmepsin-2 copy number distribution of P. falciparum isolates from Tha Song Yang district, Tak province (green). The distribution is overlaid by that of isolates from Srisaket Province on the Thai-Cambodian border (grey). The Srisaket samples were collected from malaria patients during 2015 to 2017

Table 2.

Summary of DHA-PPQ resistance markers in test samples

| Isolate ID | Year of collection | Kelch13 SNPs |

Plasmepsin-2 CNV |

Pfcrt SNPs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copy number | Classification | Exon 2 | Exon 3 | |||||

| T93S | H97Y | F145I | Other | |||||

| 1 | 2013 | C580Y | 1.2 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 2 | 2013 | C580Y | 0.7 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 3 | 2014 | – | 1.1 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 4 | 2014 | No SNPs | 1.1 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 5 | 2014 | No SNPs | 1.1 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 6 | 2014 | No SNPs | 1.1 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 7 | 2014 | R659R | 1.0 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 8 | 2014 | C580Y | 1.3 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 9 | 2014 | C580Y | 0.9 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 10 | 2014 | No SNPs | 0.6 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 11 | 2014 | No SNPs | 1.2 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 12 | 2014 | No SNPs | 1.2 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 13 | 2014 | No SNPs | 1.2 | Single | - | - | F145 | No SNPs |

| 14 | 2014 | No SNPs | 0.9 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 15 | 2014 | G538V | 1.1 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 16 | 2014 | G533S | 1.1 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 17 | 2014 | G533S | 0.9 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 18 | 2014 | No SNPs | 1.1 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 19 | 2014 | No SNPs | 1.3 | Single | T93 | H97 | – | – |

| 20 | 2014 | G533S | 1.1 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 21 | 2014 | G533S | 1.3 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 22 | 2014 | No SNPs | 0.9 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 23 | 2014 | No SNPs | 1.0 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 24 | 2015 | G533S | 1.0 | Single | – | – | F145 | No SNPs |

| 25 | 2015 | G533S | 1.0 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 26 | 2015 | No SNPs | 0.9 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 27 | 2015 | No SNPs | 0.9 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 28 | 2015 | G533S | 0.8 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 29 | 2015 | No SNPs | 1.0 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 30 | 2015 | – | 1.4 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 31 | 2015 | G533S | 0.8 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 32 | 2015 | G538V | 0.9 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 33 | 2015 | No SNPs | – | – | T93 | H97 | – | – |

| 34 | 2015 | G533S | 1.0 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 35 | 2015 | G533S | 0.9 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 36 | 2015 | No SNPs | 0.9 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 37 | 2015 | No SNPs | 0.9 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 38 | 2015 | No SNPs | 0.5 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 39 | 2015 | No SNPs | 0.9 | Single | - | - | F145 | No SNPs |

| 40 | 2015 | No SNPs | 1.2 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 41 | 2015 | G533S | 1.1 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 42 | 2016 | No SNPs | 1.2 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 43 | 2018 | G533S | 0.9 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 44 | 2018 | No SNPs | 0.8 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 45 | 2018 | C580Y | 1.0 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 46 | 2018 | C580Y | 1.1 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 47 | 2018 | G533S | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 48 | 2018 | G533S | 0.8 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 49 | 2019 |

G533S A564A |

– | – | – | – | 145I | S140P |

| 50 | 2019 | G533S | – | – | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 51 | 2019 | G533S | 1.0 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 52 | 2019 | G533S | – | – | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 53 | 2019 | G533S | 0.9 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 54 | 2019 | G533S | – | – | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 55 | 2019 | G533S | 0.8 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 56 | 2019 | G533S | 0.8 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

| 57 | 2019 | G533S | 1.1 | Single | T93 | H97 | F145 | No SNPs |

No data

Discussion

Over the last decade, there has been remarkable progress in controlling P. falciparum malaria in the Greater Mekong subregion [1]. Likewise, in Thailand the reported case number of P. falciparum malaria declined from 15,740 in 2013 to 638 in 2019 [20]. In Tha Song Yang district, the annual P. falciparum malaria case numbers were 2388, 941, 352, 68, 17, 53, and 27 during 2013–2019 [20]. However, this achievement is still under the risk of resistance to antimalarials. In 2008–2009, slow parasite clearance after artemisinin therapy of falciparum malaria was first documented in western Cambodia, and presumed to reflect emerging artemisinin resistance [2, 3]. Since then, artemisinin resistance has spread or emerged independently throughout the Greater Mekong subregion [4, 10, 21]. As a result of the falling efficacy of artemisinin-mefloquine in Thailand, DHA-PPQ was introduced as the first-line treatment in 2015 [8, 22]. However, treatment failure soon appeared in the eastern border region of Thailand, coinciding with observations of PPQ resistance in Cambodia [11, 13, 23–25]. At present, markers of resistance to artemisinin and PPQ have been identified [5, 9, 12, 16, 17, 26].

Kelch13 mutations are the most well-established markers of artemisinin resistance [21, 27]. It has been shown that whereas C580Y was the main mutation in the eastern GMS, F446I was more common in Myanmar [10]. C580Y has now been found in many parts of Thailand but has become near fixation along the Cambodian border [4, 10, 15, 28]. The distributions of other kelch13 alleles in the country vary geographically—with Y493H and R539T found mainly in the east, P574L in the west, and R561H in northwest [28]. In this study, a new mutation, G533S, was detected in 2014 and became the most common resistance mutation in the study site. This mutation was not detected in a previous study from the area in 2012–2014 [28]. Despite this, the timing of its first detection in 2014 and the study site’s proximity to Myanmar and China agreed with the G533S appearance on the China-Myanmar border at around the same time [19]. Importantly, the frequency of G533S rose significantly, and in 2019 all 9 specimens examined had this mutation. Although this mutation has not been formally associated with clinical resistance, parasites carrying this mutation were recently shown to have elevated ring-stage survival compared to the wild-type parasite [19].

Amplification of plasmepsin-2 is widely used as a marker to trace PPQ resistance [9, 12–15]. Previous studies suggested that this genotype was restricted to eastern GMS [10, 14, 15]. Consistent with these reports, none of the P. falciparum isolates in Tak province from 2013 to 2019 had plasmepsin-2 amplification.

The second molecular marker of PPQ resistance is Pfcrt [16, 29]. Several mutations including T93S, H97Y, and F145I were implicated in treatment failure [13, 26]. The frequencies of these mutations have risen in eastern GMS [14, 15], but remained much less prevalent in the Thai-Myanmar border region [30]. In the present study, no parasite had T93S and H97Y and only one parasite had F145I. Because the F145I mutation has been shown to confer a high level of resistance of PPQ through transfection [16] and be associated with a five-fold increased risk of DHA-PPQ treatment failure [26], the detection of this mutation raises concern over its potential future establishment in the area.

In summary, this study detected for the first time the kelch13 G533S mutation in Tak province of western Thailand. This mutation has been associated with artemisinin resistance in vitro [19] and its increase in frequencies was observed during 2014–2019. In addition, although no plasmepsin-2 amplification was observed, the PPQ resistance Pfcrt F145I mutation was detected in a parasite that also carried the G533S mutation. Given the threat of drug resistance, close monitoring of resistance markers and treatment failure in the area is well warranted.

Limitations

The study involved a small number of samples—55 for kelch13 mutation, 51 for plasmepsin-2 amplification, and 54 for Pfcrt mutation—from one district of Tak Province, Thailand. The low number of samples per year, particularly from 2016 onwards, was due to the low incidence of P. falciparum malaria in the study site. As such, the study has limited power to detect rare mutations and the results may not be representative of the broader area of western Thailand. In addition, although the kelch13 G533S was first detected in 2014, its first emergence in the study area may have been earlier.

Conclusions

Thailand is eliminating malaria, but the development of resistance against the current national first-line drug DHA-PPQ would hinder the progress. Indeed, in Srisaket and Ubon Ratchathani provinces in Northeastern Thailand, the first-line treatment had to be changed to pyronaridine-artesunate (Pyramax™) in 2019 due to the decreased efficacy of DHA-PPQ [31]. For the northwestern area in this study, the predominance of the kelch13 G533S could be a warning sign of developing resistance. Thus, the resistance markers and treatment efficacy in this area should be closely monitored.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Primers used in analysis of DHA-PPQ resistance markers. Table S2. Thermocycling condition of plasmepsin-2 amplification by SYBR Green real-time PCR. Table S3. Thermocycling condition of exon 2 and exon 3 of Pfcrt gene amplification.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all staff from Mahidol Vivax Research Unit who made the study possible. We would like to thank the staff from Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University for their support and Prof. Sasithon Pukrittayakamee for specimen sharing.

Abbreviations

- DBS

Dry blood spots

- CNV

Copy number variation

- DHA

Dihydroartemisinin

- Pfcrt

P. falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter

- PPQ

Piperaquine

- SNPs

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

Author contributions

KNW designed the study, performed experiments, analysed data, and wrote the first draft manuscript. SL, LC, KC and JS contributed the specimens, analysed data, and review the manuscript. WN conceived of the project, designed the study, reviewed data, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. KM, KP, and CS performed and helped in molecular genotyping and plasmepsin-2 amplification. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research project was supported by a grant from the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the National Institute of Health (U19 AI089672).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted under approval from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University (MUTM 2021-008-01) and the Central Research Ethics Committee, Thailand (CREC003/58).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . World malaria report 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noedl H, Se Y, Schaecher K, Smith BL, Socheat D, Fukuda MM. Evidence of artemisinin-resistant malaria in western Cambodia. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2619–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0805011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dondorp AM, Nosten F, Yi P, Das D, Phyo AP, Tarning J, et al. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:455–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imwong M, Suwannasin K, Kunasol C, Sutawong K, Mayxay M, Rekol H, et al. The spread of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in the Greater Mekong subregion: a molecular epidemiology observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:491–497. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30048-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ariey F, Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Beghain J, Langlois AC, Khim N, et al. A molecular marker of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2014;505:50–55. doi: 10.1038/nature12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ocan M, Akena D, Nsobya S, Kamya MR, Senono R, Kinengyere AA, et al. K13-propeller gene polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum parasite population in malaria affected countries: a systematic review of prevalence and risk factors. Malar J. 2019;18:60. doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-2701-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menard D, Khim N, Beghain J, Adegnika AA, Shafiul-Alam M, Amodu O, et al. A worldwide map of Plasmodium falciparum K13-propeller polymorphisms. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2453–2464. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . World malaria report 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Witkowski B, Duru V, Khim N, Ross LS, Saintpierre B, Beghain J, et al. A surrogate marker of piperaquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria: a phenotype-genotype association study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:174–183. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30415-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imwong M, Dhorda M, Myo Tun K, Thu AM, Phyo AP, Proux S, et al. Molecular epidemiology of resistance to antimalarial drugs in the Greater Mekong subregion: an observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:1470–1480. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30228-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amaratunga C, Lim P, Suon S, Sreng S, Mao S, Sopha C, et al. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: a multisite prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:357–365. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00487-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amato R, Lim P, Miotto O, Amaratunga C, Dek D, Pearson RD, et al. Genetic markers associated with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine failure in Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: a genotype–phenotype association study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:164–173. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30409-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Pluijm RW, Imwong M, Chau NH, Hoa NT, Thuy-Nhien NT, Thanh NV, et al. Determinants of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine treatment failure in Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam: a prospective clinical, pharmacological, and genetic study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:952–961. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30391-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imwong M, Suwannasin K, Srisutham S, Vongpromek R, Promnarate C, Saejeng A, et al. Evolution of multidrug resistance in Plasmodium falciparum: a longitudinal study of genetic resistance markers in the Greater Mekong Subregion. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2021;65:e0112121. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01121-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boonyalai N, Thamnurak C, Sai-Ngam P, Ta-Aksorn W, Arsanok M, Uthaimongkol N, et al. Plasmodium falciparum phenotypic and genotypic resistance profile during the emergence of piperaquine resistance in Northeastern Thailand. Sci Rep. 2021;11:13419. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-92735-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross LS, Dhingra SK, Mok S, Yeo T, Wicht KJ, Kumpornsin K, et al. Emerging Southeast Asian PfCRT mutations confer Plasmodium falciparum resistance to the first-line antimalarial piperaquine. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3314. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05652-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boonyalai N, Vesely BA, Thamnurak C, Praditpol C, Fagnark W, Kirativanich K, et al. Piperaquine resistant Cambodian Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates: in vitro genotypic and phenotypic characterization. Malar J. 2020;19:269. doi: 10.1186/s12936-020-03339-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Pluijm RW, Tripura R, Hoglund RM, Pyae Phyo A, Lek D, Ul Islam A, et al. Triple artemisinin-based combination therapies versus artemisinin-based combination therapies for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria: a multicentre, open-label, randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1345–1360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30552-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J, Li N, Siddiqui FA, Xu S, Geng J, Zhang J, et al. In vitro susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum isolates from the China–Myanmar border area to artemisinins and correlation with K13 mutations. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2019;10:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thailand Malaria Elimination Program, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health. http://malaria.ddc.moph.go.th/malariaR10/index_v2.php. Accessed 22 Sep 2022.

- 21.Ashley EA, Dhorda M, Fairhurst RM, Amaratunga C, Lim P, Suon S, et al. Spread of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:411–423. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phyo AP, Ashley EA, Anderson TJC, Bozdech Z, Carrara VI, Sriprawat K, et al. Declining efficacy of artemisinin combination therapy against P. falciparum malaria on the Thai–Myanmar border (2003–2013): the role of parasite genetic factors. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:784–91. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spring MD, Lin JT, Manning JE, Vanachayangkul P, Somethy S, Bun R, et al. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine failure associated with a triple mutant including kelch13 C580Y in Cambodia: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:683–691. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leang R, Barrette A, Bouth DM, Menard D, Abdur R, Duong S, et al. Efficacy of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax in Cambodia, 2008 to 2010. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:818–826. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00686-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leang R, Taylor WR, Bouth DM, Song L, Tarning J, Char MC, et al. Evidence of Plasmodium falciparum malaria multidrug resistance to artemisinin and piperaquine in Western Cambodia: dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine open-label multicenter clinical assessment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:4719–4726. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00835-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agrawal S, Moser KA, Morton L, Cummings MP, Parihar A, Dwivedi A, et al. Association of a novel mutation in the Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter with decreased piperaquine sensitivity. J Infect Dis. 2017;216:468–476. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miotto O, Amato R, Ashley EA, MacInnis B, Almagro-Garcia J, Amaratunga C, et al. Genetic architecture of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Genet. 2015;47:226–234. doi: 10.1038/ng.3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kobasa T, Talundzic E, Sug-Aram R, Boondat P, Goldman IF, Lucchi NW, et al. Emergence and spread of kelch13 mutations associated with artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum parasites in 12 Thai provinces from 2007 to 2016. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62:e02141–e2217. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02141-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dhingra SK, Redhi D, Combrinck JM, Yeo T, Okombo J, Henrich PP, et al. A variant PfCRT isoform can contribute to Plasmodium falciparum resistance to the first-line partner drug piperaquine. mBio. 2017;8:e00303–17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00303-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ye R, Zhang Y, Zhang D. Evaluations of candidate markers of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from the China–Myanmar, Thailand–Myanmar, and Thailand–Cambodia borders. Parasit Vectors. 2022;15:130. doi: 10.1186/s13071-022-05239-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.PMI. U. S. Presient’s Malaria Initiative Thailand, Lao PDR, and Regional Malaria operational Plan FY2020.

- 32.Tha Song Yang district. Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tha_Song_Yang_district. Accessed 11 July 2022.

- 33.Tak province. Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tak_province. Accessed 11 July 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Primers used in analysis of DHA-PPQ resistance markers. Table S2. Thermocycling condition of plasmepsin-2 amplification by SYBR Green real-time PCR. Table S3. Thermocycling condition of exon 2 and exon 3 of Pfcrt gene amplification.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.