Abstract

The freshwater mussel Westralunio carteri (Iredale, 1934) has long been considered the sole Westralunio species in Australia, limited to the Southwest and listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List and under Australian legislation. Here, we used species delimitation models based on COI mtDNA sequences to confirm existence of three evolutionarily significant units (ESUs) within this taxon and conducted morphometric analyses to investigate whether shell shape differed significantly among these ESUs. “W. carteri” I was found to be significantly larger and more elongated than “W. carteri” II and “W. carteri” II + III combined, but not different from “W. carteri” III alone. We recognise and redescribe “W. carteri” I as Westralunio carteri (Iredale, 1934) from western coastal drainages and describe “W. carteri” II and “W. carteri” III as Westralunio inbisi sp. nov. from southern and lower southwestern drainages. Two subspecies are further delineated: “W. carteri” II is formally described as Westralunio inbisi inbisi subsp. nov. from southern coastal drainages, and “W. carteri” III as Westralunio inbisi meridiemus subsp. nov. from the southwestern corner. Because this study profoundly compresses the range of Westralunio carteri northward and introduces additional southern and southwestern taxa with restricted distributions, new threatened species nominations are necessary.

Subject terms: Molecular ecology, Taxonomy, DNA sequencing, RNA sequencing, Conservation biology

Introduction

There has been a growing interest in using multiple lines of evidence for delineating species boundaries, particularly for taxa such as freshwater mussels, which are highly threatened while containing undescribed cryptic diversity1–8. Before the advent of modern molecular systematics and taxonomy, new freshwater mussel species were described based primarily on shell morphology and morphometry9–11. However, recognition of freshwater mussel species based solely on morphology can be fraught with difficulties, with freshwater mussel taxonomy hindered, in part, by the tendency for shell forms to vary in response to environmental conditions12–15.

Freshwater mussels (Bivalvia: Palaeoheterodonta: Unionida) are comprised of six families with a total of 192 genera and 958 species worldwide16. Six unionidan families are recognised as distinct based on larval morphology, the number and arrangement of ctenidia demibranchs containing marsupia, water tube and brood chamber morphology in the demibranchs, the presence or absence of a supra-anal aperture and mantle fusion relative to the inhalant and exhalant siphons17,18. Most freshwater mussels have a two-stage life cycle, whereby larvae are briefly parasitic on fishes and, in some cases, amphibians for a brief period of weeks to months and live the remainder of their lives as benthic filter-feeders. Larval forms include glochidia in the Hyriidae, Margaritiferidae and Unionidae and lasidia or haustoria in Etheriidae, Iridinidae and Mycetopodidae19.

The Hyriidae have a Gondwanan origin and include at least 96 species from 16 genera with a trans-Pacific distribution in Australasia and South America14,20–23. Included amongst these genera is the freshwater mussel genus Westralunio. This genus is restricted to the Australasian region in the Southern Hemisphere and is represented by three species: Westralunio carteri (Iredale, 19349) from southwestern Australia, Westralunio flyensis (Tapparone Canefri, 188324) from Papua New Guinea and Westralunio albertisi Clench, 195725 from Papua New Guinea and eastern Indonesian West Papua14. Iredale9 erected the genus Westralunio based on hinge dentition, and established two subspecies, Westralunio amibiguus ambiguus (Philippi, 184726) and Westralunio ambiguus carteri Iredale, 19349 based on geography and shell form. McMichael & Hiscock10 later merged the two subspecies, stating that they could not be separated on anatomical or geographical grounds and elevated the name carteri to specific rank, ceding the name ambiguus to the genus Velesunio from eastern Australia. As such, W. carteri was recognised as the sole southwestern Australian freshwater mussel. McMichael & Hiscock10 also included W. flyensis and W. albertisi in the genus, stating that “Westralunio is, in most respects, a typical velesunionine mussel, but it is easily distinguished from the related genera, Velesunio and Alathyria, by its strong, grooved cardinal teeth.”

Two recent studies have investigated phylogeographic structuring and the existence of Evolutionary Significant Units (ESUs) and Molecular Operational Taxonomic Units’ (MOTUs) in W. carteri27,28. Klunzinger et al.27 applied four species delimitation models based on 46 COI mtDNA sequences spanning 13 populations of W. carteri, which revealed unanimous support for at least two MOTUs: “W. carteri” I from west coast drainages and “W. carteri” II + III from drainages of the south coast lower southwest of southwestern Australia. The degree of differentiation (2.8–3.4%) between these two putative MOTUs and their apparent allopatry, led these authors to suggest that they be recognised as distinct species. Furthermore, one of the four models revealed a potential third MOTU (“W. carteri” III), comprising individuals from the southwest corner of the region. The authors recommended further research was required to better characterise the observed differentiation among lineages and their distribution. Subsequent work by Benson et al.28 incorporated COI and 16S sequences from an additional 119 individuals from 19 populations previously unsampled and showed that the distribution of the two primary lineages rarely overlapped, and that the third lineage appeared to be restricted to just two river systems.

These two independent lines of evidence (genetics and geographical distribution) lend support to the notion that these three Westralunio lineages warrant species-level consideration and formal taxonomic description which, to date, has not been undertaken. Furthermore, W. carteri also exhibits marked intraspecific variation in shell morphology, with specimens collected from locations on the south coast29 appearing to be less elongate and having more squarely truncated posteriors than those from other parts of the species’ range (M.W. Klunzinger, pers. obs.).

As species are part of the fundamental unit of conservation assessment30, an integrated taxonomic evaluation is required for W. carteri, incorporating analyses of morphological variation and the application of species delimitation models to the full data set (i.e., combining Klunzinger et al.27 and Benson et al.28). However, this has yet to be undertaken.

The purpose of this study was to revisit the taxonomy of W. carteri based on an integrative taxonomic approach with a view to test the hypotheses that W. carteri either represents a geographically variable, single species or consists of multiple taxa worthy of taxonomic recognition. More specifically, we (i) used three species delimitation models and a comprehensive data set of COI mtDNA sequences to confirm the existence of previously identified ESUs, (ii) tested whether these taxa are morphologically distinct, and (iii) formally described the ESUs recognised for W. carteri as separate taxa.

Results

Genetic variation

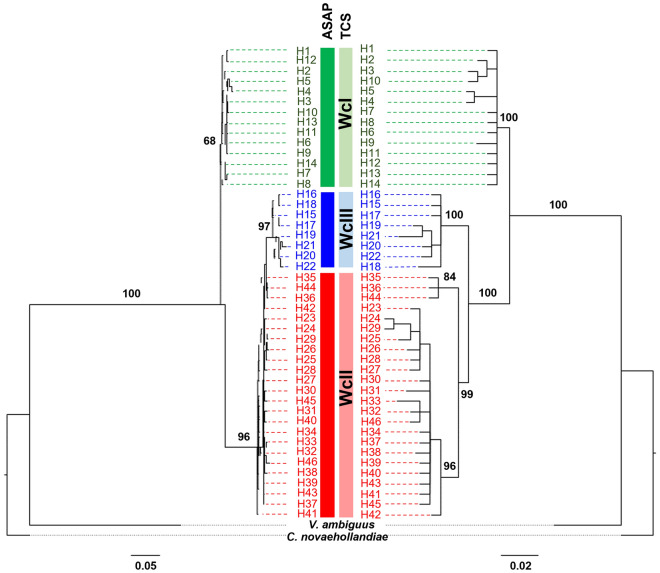

The best fitting substitution models for COI codons 1–3 were identified as TN + F + G4, F81 + F + I, and TN + F, respectively. The maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) trees showed similar topologies of the main nodes, although the BI tree displayed greater resolution of the ingroup branches (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the BI tree revealed three monophyletic clades, while two of those clades were merged in the ML tree. Two of the three molecular species delimitation methods (ASAP and TCS) recovered three groups in the BI tree as distinct taxa (Fig. 1), corresponding to the three previously described ESUs27,28. The third method (bPTP) recovered between 8 and 43 groups (mean = 28.03) suggesting that there is evidence of additional genetic differentiation within the three groups identified by ASAP and TCS. The outputs of the three methods are provided in the Supplementary information. The molecular diagnosis uncovered several fixed nucleotide differences COI characters for each taxon (Table 1: “W. carteri” I = 10; “W. carteri” II = 3; “W. carteri” III = 5). There were also 13 fixed nucleotide differences in W. carteri for the 16S gene. The remaining two taxa had no fixed nucleotide differences for the 16S gene.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic trees obtained by maximum likelihood (left) and Bayesian inference (right) analysis of “Westralunio carteri” mtDNA COI sequences, including support values for the major genetic clades [ultrafast bootstrap values (left) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (right)]. Colour coded bars show support for the three major clades by the species delimitation methods (ASAP = dark shade; TCS = lighter shade). Green = WcI = “W. carteri” I; blue = WcIII = “W. carteri” III; red = WcII = “W. carteri” II. Results of bPTP analysis not shown (see supplementary data). Haplotype names correspond to Benson et al.28. Outgroup taxa are Velesunio ambiguus (Philippi, 1847) (Hyriidae: Velesunioninae) and Cucumerunio novaehollandiae (Gray, 1834) (Hyriidae: Hyriinae: Hyridellini).

Table 1.

Molecular diagnoses of “Westralunio carteri” Evolutionarily Significant Units (ESUs) from southwestern Australia (after Bolotov et al.122 with reanalysis of data from Klunzinger et al.27 and Benson et al.28).

| ESU/taxon | Number of samples (COI/16S) | Mean COI P-distance from nearest neighbour of new species, % and (SE) | Nearest neighbour of new species (COI) | Mean 16S P-distance from nearest neighbour of new species, % and (SE) | Nearest neighbour of new species (16S) | Diagnostic characters based on the sequence alignment of congeners | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COI | 16S | ||||||

| “W. carteri” I | 60/40 | 5.02 (0.90) | “W. carteri” II | 2.95 (0.01) | “W. carteri” II | 57 G, 117 T, 210 G, 249 T, 255 C, 345 G, 423 T, 447 T, 465 A, 499 T | 137 T, 155 C, 228 C, 229 T, 260 G, 290 A, 305 G, 307 T, 310 A, 311 C, 321 T, 330 A, 460 A |

| “W. carteri” II | 92/81 | 2.74 (0.62) | “W. carteri” III | 0.57 (0.29) | “W. carteri” III | 75 A, 87 T, 318 T | None |

| “W. carteri” III | 12/9 | 2.74 (0.62) | “W. carteri” II | 0.57 (0.29) | “W. carteri” II | 69 C, 123 C, 126 T, 483 A, 526 A | None |

New taxa include “W. carteri” II and III. Supplementary files 1 and 2 contain the alignments used to determine the single pure characters and p-distances. The position of each diagnostic character refers to its location within those alignments. SE, standard error.

Variation in shell morphology

Based on results from analyses of variances (ANOVAs), shells of “W. carteri” I were significantly larger (for size metrics total length (TL), maximum height (MH), beak height (BH) and beak length (BL)) and more elongated (i.e., had a lower maximum height index (MHI)) than shells of “W. carteri” II and “W. carteri” II + III combined (Table 2). However, there was no difference in size or shape metrics between “W. carteri” I and “W. carteri” III (Table 2). The lack of significant differences in beak height index (BHI) and beak length index (BLI) among any of the taxa (Table 2) indicates that wing and anterior shell development was not discernibly different between any of the ESUs.

Table 2.

Shell size metrics [mm], shape indices [%] and scores for the first two principal components (PC) obtained by Principal Component Analysis of shape indices and 18 Fourier coefficients generated by Fourier Shape Analysis for each “Westralunio carteri” species and subspecies-level Evolutionarily Significant Units (ESUs): n, number of specimens measured; minimum (min) to maximum (max) and mean (± standard error (SE)).

| Variable | “W. carteri” I min–max | Mean ± SE | n | “W. carteri” II min–max | Mean ± SE | n | “W. carteri” III min–max | Mean ± SE | n | df | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TL | 12.00–92.00 | 59.79B ± 0.68 | 294 | 28.38–79.00 | 51.68A ± 0.90 | 140 | 45.00–84.00 | 58.46AB ± 2.89 | 12 | 443 | 24.5 | < 0.0001 |

| MH | 8.50–59.00 | 37.25B ± 0.39 | 294 | 18.56–52.00 | 33.91A ± 0.57 | 140 | 32.00–50.00 | 37.92AB ± 1.34 | 12 | 443 | 12.33 | < 0.0001 |

| BH | 7.00–54.00 | 33.88B ± 0.39 | 294 | 14.72–49.00 | 30.63A ± 0.55 | 140 | 28.00–46.00 | 34.04AB ± 1.37 | 12 | 443 | 11.87 | < 0.0001 |

| BL | 4.00–30.00 | 19.04B ± 0.24 | 294 | 9.00–28.00 | 16.14A ± 0.29 | 140 | 13.00–26.00 | 17.75AB ± 1.01 | 12 | 443 | 26.78 | < 0.0001 |

| MHI | 0.46–0.89 | 0.63A ± 0.00 | 294 | 0.55–0.74 | 0.66B ± 0.00 | 140 | 0.60–0.71 | 0.65AB ± 0.01 | 12 | 443 | 28.23 | < 0.0001 |

| BHI | 0.76–1.04 | 0.91A ± 0.00 | 294 | 0.79–0.99 | 0.90A ± 0.00 | 140 | 0.84–0.93 | 0.90A ± 0.01 | 12 | 443 | 1.039 | 0.355 |

| BLI | 0.22–0.49 | 0.32A ± 0.00 | 294 | 0.23–0.51 | 0.32A ± 0.00 | 140 | 0.28–0.35 | 0.30A ± 0.01 | 12 | 443 | 1.775 | 0.171 |

| PC1 (indices) | − 3.94–6.36 | − 0.04A ± 0.07 | 294 | − 2.37–5.10 | 0.11A ± 0.10 | 140 | − 1.43–1.11 | − 0.24A ± 0.20 | 12 | 443 | 1.058 | 0.348 |

| PC2 (indices) | − 4.04–3.87 | − 0.21B ± 0.06 | 294 | − 1.87–2.85 | 0.40A ± 0.07 | 140 | − 1.00–1.80 | 0.43AB ± 0.25 | 12 | 443 | 17.61 | < 0.0001 |

| PC1 (Fourier) | − 0.079–0.047 | 0.003B ± 0.001 | 273 | − 0.057–0.048 | − 0.007A ± 0.002 | 126 | − 0.027–0.032 | − 0.001AB ± 0.006 | 12 | 408 | 12.2 | < 0.0001 |

| PC2 (Fourier) | − 0.048–0.062 | 0.003B ± 0.001 | 273 | − 0.047–0.035 | − 0.006A ± 0.001 | 126 | − 0.032–0.021 | − 0.004AB ± 0.004 | 12 | 408 | 12.06 | < 0.0001 |

| Variable | “W. carteri” II + III min–max | Mean ± SE | n | df | F | P | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TL | 28.38–84.00 | 52.22 ± 0.87 | 152 | 444 | 44.73 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| MH | 18.56–52.00 | 34.23 ± 0.54 | 152 | 444 | 20.52 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| BH | 14.72–49.00 | 30.90 ± 0.52 | 152 | 444 | 20.64 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| BL | 9.00–28.00 | 16.27 ± 0.28 | 152 | 444 | 51.54 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| MHI | 0.55–0.74 | 0.66 ± 0.00 | 152 | 444 | 56.48 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| BHI | 0.79–0.99 | 0.90 ± 0.00 | 152 | 444 | 1.833 | 0.176 | ||||||

| BLI | 0.23–0.51 | 0.31 ± 0.00 | 152 | 444 | 2.442 | 0.119 | ||||||

| PC1 (indices) | − 2.37–5.10 | 0.08 ± 0.10 | 152 | 444 | 1.131 | 0.288 | ||||||

| PC2 (indices) | − 1.87–2.85 | 0.40 ± 0.07 | 152 | 444 | 35.29 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| PC1 (Fourier) | − 0.057–0.048 | − 0.006 ± 0.001 | 138 | 409 | 23.32 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| PC2 (Fourier) | − 0.047–0.035 | − 0.006 ± 0.001 | 138 | 409 | 23.91 | < 0.0001 |

P-value (P), degrees of freedom (df) and F-ratio (F) were obtained from ANOVAs comparing “W. carteri” I, II and III (upper section of the Table) and “W. carteri” I and II + III (lower section of the Table), respectively. P-values < 0.05 in bold; different superscript letters indicate significant differences between groups in Tukey’s pairwise posthoc-test. Shell size metrics: TL total length, distance from anterior to posterior apices of valve; MH maximum height, distance from ventral edge to apex of posterior ridge; BH beak height, distance from ventral edge to beak apex; BL beak length, distance from anterior apex of valve to the 90-degree vertex aligning with the beak apex. Shape indices determined as: MHI = MH/TL, BHI = BH/MH, and BLI = BL/TL.

This pattern was partly confirmed in the principal component analysis (PCA) of these three shell shape indices, where PC1, largely explained by variation in BLI (Fig. 2A), did not differ between the two species (i.e., “W. carteri” I vs. “W. carteri” II + III) or among the three taxa (Table 2). The PC2, largely explained by variation in MHI and BHI (Fig. 2A), differed significantly between “W. carteri” I and “W. carteri” II (Table 2). Accordingly, 70% (70% jack-knifed) of specimens were assigned to the correct species in the corresponding discriminant analysis (DA), whilst this was true for only 55% (54%) at the MOTU-level.

Figure 2.

Scatterplots of the first two PC axes obtained by PCA on (A) calculated shape indices based on shell measurements, and (B) 18 Fourier coefficients for “Westralunio carteri” I, “W. carteri” II and “W. carteri” III. 95% Confidence Intervals are displayed at the species level, i.e., for “W. carteri” I (full line) and “W. carteri” II + III (dashed line). Extreme shell outlines in (B) are depicted to visualise trends in sagittal shell shape, along PC axes.

The difference in shell elongation between “W. carteri” I and “W. carteri” II was confirmed by Fourier shape analysis. As visualised by synthetic outlines in Fig. 2B, shell elongation is expressed along the PC1 (explaining 15% of total variation in Fourier coefficients). The PC1 as well as PC2 scores differed significantly between the two species (i.e., “W. carteri” I vs. “W. carteri” II + III) as well as between “W. carteri” I and “W. carteri” II, respectively (Table 2). Combined with synthetic outlines, this indicated a tendency towards a more elongated, somewhat wedge-shaped shell in “W. carteri” I, whilst “W. carteri” II shells tended to be relatively high with a stout anterior margin (Fig. 2B). An analysis of similarities (ANOSIM) analysis on all Fourier coefficients revealed no significant difference between the two species (i.e., “W. carteri” I vs. “W. carteri” II + III; ANOSIM: R = − 0.018, p = 0.097), but did indicate a significant difference between the three ESUs (ANOSIM: R = 0.0625, p = 0.0051). Specifically, “W. carteri” I differed significantly from “W. carteri” II (Bonferroni-corrected p = 0.0009). Only 66% and 65% (62% and 62% jack-knifed) of specimens were assigned to the correct species and taxon in DAs on that dataset, respectively.

Taxonomic accounts

Class: Bivalvia Linnaeus, 175831.

Subclass: Autobranchia Grobben, 189432.

Infraclass: Heteroconchia Gray, 185433.

Cohort: Palaeoheterodonta Newell, 196534.

Order: Unionida Gray, 185433 in Bouchet & Rocroi, 201035.

Superfamily: Unionoidea Rafinesque, 182036.

Family: Hyriidae Parodiz & Bonetto 196337.

Genus: Westralunio Iredale, 19349.

Type species: Westralunio ambiguus carteri Iredale, 19349 (by original designation).

Redescription: Westralunio carteri (Iredale, 1934)

Synonymy

Unio australis Lamarck38: Menke39, p. 38, specimen 219. (Non Unio australis Lamarck, 181938).

Unio moretonicus Reeve40: Smith41, p. 3, pl. iv, Fig. 2. (misidentified reference to Unio moretonicus Reeve, 186540).

Hyridella australis (Lam.38): Cotton & Gabriel42 (in part), p. 156. (misidentified reference to Unio australis Lamarck, 181938).

Hyridella ambigua (Philippi26): Cotton & Gabriel42 (in part), p. 157. (misidentified reference to Unio ambiguus Philippi, 184726).

Westralunio ambiguus carteri: Iredale, 19349, p. 62.

Westralunio ambiguus (Philippi26): Iredale9, p. 62, pl. iii, Fig. 8, pl. iv, Fig. 8. (Non Unio ambiguus Phil. 184726), Iredale43, p. 190.

Figure 8.

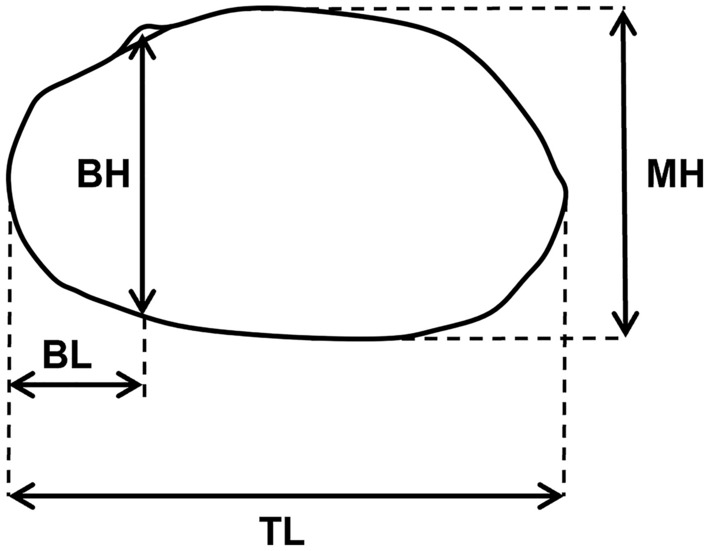

Measurement scheme used to quantify freshwater mussel size in this study, redrawn from McMichael & Hiscock10. BH beak height, BL beak length, MH maximum height, TL total length.

Centralhyria angasi subjecta Iredale, 19349, p. 67 (in part), Iredale43, p. 190.

Westralunio carteri Iredale9: McMichael & Hiscock10pl. viii, Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7, pl. xvii, Figs. 4, 5.

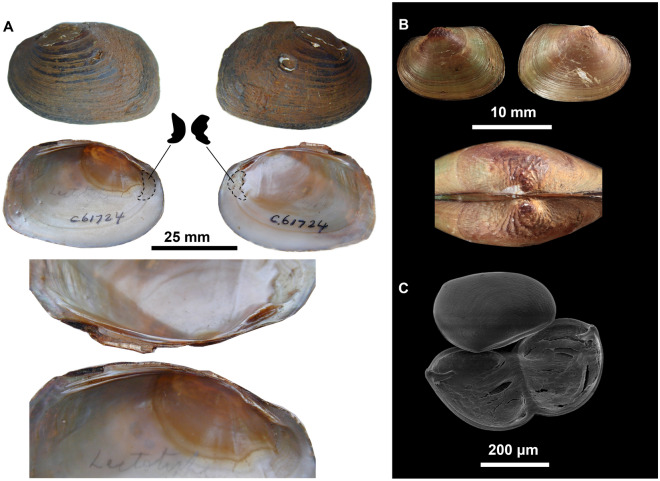

Figure 3.

(A) Westralunio ambiguus carteri Iredale, 1934, Lectotype: Victoria Reservoir, Darling Range, 12 mi E of Perth, AMS C.061724. Detail of fusion in anterior muscle scars from either valve represented by dashed lines and black polygons. Bottom image showing detail of hinge teeth. Photos provided with permission by Dr Mandy Reid, AMS. (B) Valves and detail of sculptured umbo of a juvenile W. carteri from Yule Brook, Western Australia, UMZC 2013.2.9. Photo by Dr Michael W. Klunzinger. (C) Glochidia of W. carteri from Canning River, Western Australia. Photo by Dr Michael W. Klunzinger.

Figure 4.

(A) Victoria Reservoir, Canning River, near Perth, Western Australia, type locality for W. carteri. Photo by Corey Whisson. (B) Goodga River, Western Australia, type locality for W. inbisi inbisi, at vertical slot fishway where holotype of W. inbisi inbisi was collected from. Photo provided with permission by Dr Stephen J. Beatty. (C) Margaret River, Western Australia, type locality for W. inbisi meridiemus, at Apex Weir. Photo by Dr Michael W. Klunzinger.

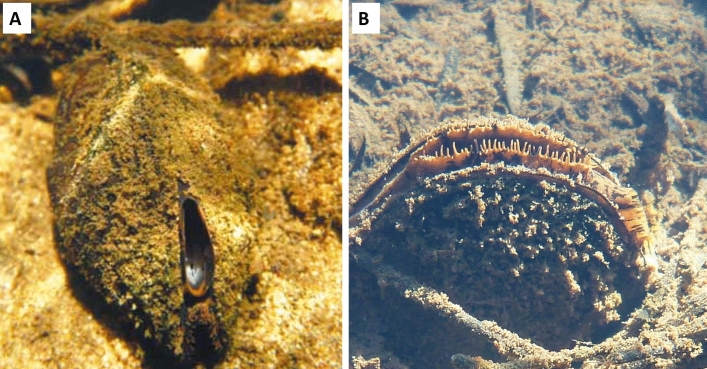

Figure 5.

Live specimens of actively filtering freshwater mussels in the burrowed position. (A) Westralunio carteri (Iredale, 1934), Canning River at Kelmscott, Western Australia, inhalant siphon with 2–4 rows of papillae oriented toward substrate. Photo by Dr Michael W. Klunzinger. (B) Westralunio inbisi meridiemus subsp. nov., Canebreak Pool, Margaret River, Western Australia; inhalant siphon edges lined with protruding papillae facing towards water surface, away from substrate. Photo by Dr Michael W. Klunzinger.

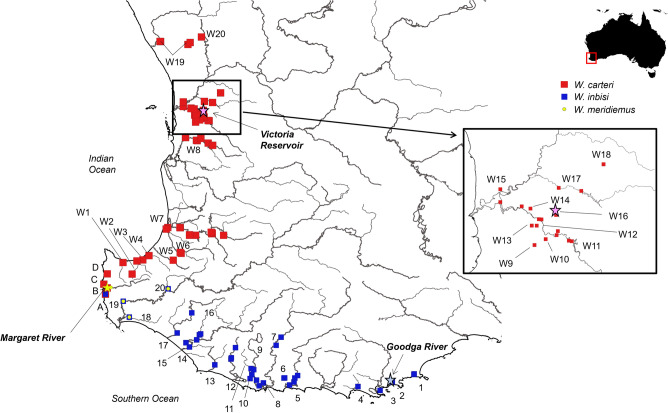

Figure 6.

Distribution of the Westralunio specimens used for analyses in this study. Stars indicate type localities, labelled in bold, with colours corresponding to taxa (red—W. carteri, blue—W. inbisi inbisi, yellow—W. inbisi meridiemus). Waterbodies: South Coast: 1—Waychinicup R, 2—Goodga R, 3—King George Sound (N.B. museum records provided locality which we presume include freshwater streams or rivers draining to King George Sound rather than being collected from the marine environment), 4—Marbellup Bk, 5—Kent R, 6—Bow R, 7—Frankland R, 8—Walpole R, 9—Deep R, 10—Inlet R, 11—Weld R, 12—Shannon R, 13—Gardner R, 14—Warren R, 15—Lk Yeagarup, 16—Lefroy Bk, 17—Donnelly R, 18—Scott R, 19—Chapman Bk, 20—St. John Bk; Capes: A—Boodjidup Bk, B—Ellens Bk, C—Margaret R, D—Wilyabrup Bk; West Coast: W1—Carbunup R, W2—Vasse R, W3—Abba R, W4—Ludlow R, W5—Capel R, W6—Preston R, W7—Collie R, W8—Serpentine Res/R/Birrega Drain, W9—Wungong Bk, W10—Neerigen Bk, W11—Canning Res, W12—Canning R, W13—Southern R, W14—Yule Bk, W15—Swan R, W16—Victoria Res, W17—Helena R, W18—Lk Leschenaultia, W19—Gingin Bk, W20—Marbling Bk. Mapping methods provided in text. River basins within the South West Coast Drainage Division of Australia as defined under AWRC102. Spatial data were mapped as vector data in QGIS Desktop 3.24.3 (https://qgis.org/en/site/) using the GCS_GDA_1994 coordinate system103. The country outline for Australia was drawn from the GADM database (www.gadm.org), version 2.0, December 2011 under license. The rivers were mapped from the Linear (Hierarchy) Hydrography of Western Australia dataset (https://catalogue.data.wa.gov.au/dataset/hydrography-linear-hierarchy/resource/9908c7d1-7160-4cfa-884d-c5f631185859), under license.

Figure 7.

Westralunio inbisi inbisi subsp. nov., (A) Paratype: Goodga River, Western Australia, WAM S5620. Detail of fusion in anterior muscle scars from either valve represented by dashed lines and black polygons. Bottom image showing detail of hinge teeth. Photos by Corey Whisson. (B) Holotype: Goodga River, Western Australia, WAM S82756. Photo by Corey Whisson. (C) Valves and detail of sculptured umbo of a juvenile, Lake Yeagarup, Western Australia, WAM S82697. Photo by Dr Michael W. Klunzinger. (D) Westralunio inbisi meridiemus subsp. nov. Holotype: Margaret River, Western Australia, WAM S56235. Photo by Corey Whisson.

Type material

Lectotype: AMS C.61724 (Fig. 3A) Westralunio ambiguus carteri Iredale, 19349.

Paralectotypes: AMS C.170635 Westralunio ambiguus carteri Iredale, 19349 (n = 4).

Type locality: Victoria Reservoir, Darling Range, 12 miles east of Perth, Western Australia (Fig. 4A).

Lectotype: BMNH 1840–10-21–29 Centralhyria angasi subjecta Iredale (selected by McMichael & Hiscock10).

Type locality: Avon River, Western Australia.

Material examined for redescription: For W. carteri (= “W. carteri” I), molecular data examined included 52 and 61 individual COI mtDNA and 16S rDNA sequences, respectively, for species delimitation. Additionally, Fourier shell shape outline analysis and traditional shell morphometric measurements were examined from 238 and 290 individuals, respectively. Complete details on all specimens examined are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

ZooBank registration: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:6B740F4D-40C3-4D6A-8938-B0FD7FD1F6D7.

Etymology: The species name carteri is most likely named after the surname of the collector who provided original type specimens to the Australian Museum, although Iredale9 did not specify this as the case. We have applied ICZN Articles 46.1 and 47.144, designating W. carteri as the nominotypical species.

Revised diagnosis: Specimens of W. carteri are distinguished from other Australian Westralunio taxa by having shell series that are significantly larger and more elongated than Westralunio inbisi inbisi subsp. nov., but not different from Westralunio inbisi meridiemus subsp. nov. The species has 10 diagnostic nucleotides at COI (57 G, 117 T, 210 G, 249 T, 255 C, 345 G, 423 T, 447 T, 465 A, 499 T) and 13 at 16S (137 T, 155 C, 228 C, 229 T, 260 G, 290 A, 305 G, 307 T, 310 A, 311 C, 321 T, 330 A, 460 A), which differentiate it from its sister taxa, W. inbisi inbisi and W. inbisi meridiemus (each described below) using ASAP and TCS species delimitation models.

Redescription

This species is of the ESU “W. carteri” I27,28.

Shell morphology: Shells of relatively small to medium size, generally less than 70 mm in length, but to a maximum length of approximately 100 mm10,45, MHI 46–89%; anterior portion of shell with moderate development, BLI 22–49%; larger shells with abraded umbos scarcely winged; wing development variable, generally decreasing with size, BHI 76–104% (Table 2). Shell outline oblong-ovate to rounded; posterior end obliquely to squarely truncate, anterior end round; ventral edge slightly curved, nearly straight in larger specimens; hinge line curved, hinge strong. Umbos usually abraded in specimens > 20 mm in length; unabraded umbos with distinctive v- or w-shaped plicated sculpturing (Fig. 3B and Zieritz et al.46). Shell substance typically thick; shells of medium width with pronounced posterior ridge; periostracum smooth, dark brown to reddish, with fine growth lines. Pallial line less developed in smaller specimens and prominent only in large specimens (e.g., > 60 mm TL). Lateral teeth longer and blade-like, slightly serrated to smooth and singular in left valve, fitting into deep groove in right valve; pseudocardinal tooth in right valve coarsely serrated, thick, and erect, fitting into deeply grooved socket in left valve. Anterior muscle scars well impressed and anchored deeply in larger specimens; anterior retractor pedis and protractor pedis scars both small and fused with adductor muscle scar; posterior muscle scars lightly impressed; dorsal muscle scars usually with two or three deep pits anchored to internal umbo region.

Anatomy: Supra-anal opening absent, siphons of moderate size, not prominent but protrude beyond shell margin in actively filtering live specimens, pigmented dark brown with mottled lighter brown to orange splotches; inhalant siphon aperture about 1.5 times size of exhalant and bearing 2–4 rows of internal papillae (Fig. 5A); ctenidial diaphragm relatively long and perforated. Outer lamellae of outer ctenidia completely fused to mantle, inner lamellae of inner ctenidia fused to visceral mass then united to form diaphragm; palps relatively small, usually semilunar in shape; marsupium well developed as a distinctive swollen interlamellar space in the middle third of the inner ctenidium of females. Outer ctenidia in both sexes thin, with numerous, short intrafilamentary junctions and few, irregular interlamellar junctions; in females similar, but marsupium has numerous, tightly packed, well-developed interlamellar junctions. Thus, brooding in females is endobranchous.

Life history: Sexes are separate in W. carteri, and hermaphroditism appears to be rare47–49. Males and females both produce gametes year-round but brooding of glochidia appears to be seasonal and ‘tachyticitc’ (i.e., as defined by Bauer & Wächtler19, fertilisation and embryonic development occurring in late winter/early spring and glochidia release in early summer)50. Glochidia are released within vitelline membranes, embedded in mucus which extrude from exhalant siphons of females (i.e., 'amorphous mucus conglutinates') during spring/summer. Glochidia attach to host fishes and live parasitically on fins, gills or body surfaces for 3–4 weeks while undergoing metamorphosis to the juvenile stage. Host fishes which have been shown to support glochidia metamorphosis to the juvenile stage in the laboratory include Afurcagobius suppositus (Sauvage, 188051), Gambusia holbrooki (Girard, 185952), Nannoperca vitttata (Castelnau, 187353), Pseudogobius olorum (Sauvage, 188051) and Tandanus bostocki Whitley, 194454 but not Carassisus auratus Linnaeus, 175831 or Geophagus brasiliensis (Quoy & Gaimard, 182455)47. Wild-caught fishes observed to be carrying W. carteri glochidia have included A. suppositus, Bostockia porosa Castelnau, 187353, G. holbrooki, Galaxias occidentalis Ogilby, 189956, N. vittata, P. olorum, T. bostocki, Leptatherina wallacei (Prince, Ivantsoff & Potter, 198257), and Phalloceros caudimaculatus (Hensel, 186858)47. Juveniles which have detached from host fishes have a characteristic ciliated foot and two distinct adductor muscles47. Probable age at maturity is 4–6 years old and estimated longevity is at least 36 to 52 years59. Inheritance of mitochondria is doubly uniparental60.

Glochidium: Following release, glochidia hatch from vitelline membranes but remain tethered by a larval thread and characteristically ‘wink’; valves with single adductor muscle; shells subtriangular and scalene in shape with smooth surface which lack surface spikes and dotted with pores, 305–310 μm long, 249–253 μm high and have a hinge length of 210–214 μm; apex of the ventral edge protrudes and is off-centre and closest to the posterior region of the glochidial shell, giving a sub-triangular scalene shape; larval teeth slightly curved towards adductor muscle with concave protuberance on base of the right valve tooth and convex protuberance on base of the left valve tooth; larval tooth of the right valve lanceolate, terminating with three sharp cusps; tooth of left valve blunt with two rounded cusps and groove at the midpoint to accommodate the middle cusp of the right valve; larval teeth lack microstylets (Fig. 3C and Klunzinger et al.48).

Distribution: Found in freshwater catchments from Gingin Brook, north of Perth to westerly flowing drainages north and west of the Blackwood River, within 150 km of the coast28,61 (Fig. 6).

Habitat: Found in freshwater streams, rivers and sometimes lakes or wetlands with permanent water, salinities less than about 3.0 mg/L, pH ranging from about 4.5 to 10 and more common in habitats not prone to nutrient pollution61.

Comments: McMichael & Hiscock10 suggested that the species aligns with other Velesunioninae in having smooth umbos, later refuted by Zieritz et al.46, as illustrated in Fig. 3B. Additionally, Iredale9 separated the genus Westralunio from Velesunio based on adult hinge tooth morphology, such that pseudocardinal hinge teeth are erect, serrated and strongly grooved in Westralunio as opposed to Velesunio which are suggested as not serrated and not strongly grooved. We contend that while W. carteri typically does have serrated pseudocardinal teeth that are usually erect/conspicuous and strongly grooved, so too are some Velesunio specimens (M. Klunzinger, unpublished data). In terms of distribution, there is one record of a specimen from the Gascoyne River collected ca. 1891 (BMNH-MP-110 listed as Diplodon ambiguus Parreyss in Philippi26 = Unio philippianus Küster, 186162; from Graf & Cummings63) which is well north of the species currently known range boundary. It is unclear whether the species occurs in that river as it has not been collected from north of the Moore-Hill Basin apart from this individual record.

Westralunio flyensis (Tapparone Canefri, 1883)

Synonymy

Unio (Bariosta) flyensis Tapparone Canefri, 188324, pp. 293–294, text Fig. 1.

Diplodon (Hyridella) flyensis (Tapp. Can.24), Simpson64, p. 1295.

Hyridella flyensis (Tapp. Can.24), Haas65, pp. 74–75, pl. ii, Figs. 4 and 5.

Type material

Holotype: The Holotype is held at Museo Civico di Storia Naturale, Genoa, Italy.

Paratypes: Two Paratypes are held at Museo Civico di Storia Naturale, Genoa, Italy.

Type Locality: Fly River, Papua New Guinea.

Description: As described by McMichael & Hiscock10.

Distribution: Southern rivers of New Guinea.

Westralunio albertisi Clench, 1957

Type material

Holotype: MCZ 212908.

Paratype: AMS C.62268.

Type Locality: inland from Daru, Papua.

Paratype: MCZ 191391, Lake Murray, Fly River, Papua New Guinea.

Description: As described by McMichael & Hiscock10.

Distribution: Lakes of the Fly River district, Papua New Guinea.

Westralunio inbisi sp. nov.

Westralunio inbisi inbisi subsp. nov.

Type material

Holotype: WAM S82756 (Fig. 7A–C), collected by M.W. Klunzinger.

Type locality: Goodga River at vertical slot fishway, Western Australia (34.9485°S, 118.0799°E, GDA94) (see Fig. 4B).

Paratypes: WAM S56200, WAM S56201, WAM S56202, WAM S56203, collected by M. W. Klunzinger.

Type locality: Goodga River, Western Australia (34.9597°S, 118.0981°E, GDA94).

Material examined: For W. inbisi inbisi (= “W. carteri” II), molecular data examined included 82 and 93 individual 16S rDNA and COI mtDNA sequences, respectively, for species delimitation. Additionally, Fourier shell shape outline analysis and traditional shell morphometric measurements were examined from 127 and 139 individuals, respectively. Complete details on all specimens examined are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Etymology: The specific epithet, inbisi, is derived from the Nyoongar word ‘inbi’, translating to ‘mussel, fresh water’ in English67.

Diagnosis: Specimens of W. inbisi inbisi are distinguished from other Australian Westralunio taxa by having shell series that are significantly smaller and less elongated than W. carteri, but not W. inbisi meridiemus. The subspecies has three diagnostic nucleotides at COI (75 A, 87 T, 318 T) and none at 16S, which differentiate it from its sister taxa, W. carteri and W. inbisi meridiemus using ASAP and TCS species delimitation models.

Description: This subspecies is of the ESU “W. carteri” II27,28. Shell morphology in juveniles and adults same as W. carteri as described above (see Fig. 7A–C). Total adult shell length generally < 80 mm but known to reach in excess of 90 mm68,69. MHI 55–74%; anterior portion of shell with moderate development, BLI 23–51%; larger shells with abraded umbos scarcely winged; wing development variable, generally decreasing with size, BHI 79–99% (Table 2); anatomy same as W. carteri; life history: sexes appear to be separate based on macroscopic examinations of marsupia in non-gravid and gravid females, examined in the field in September and March 2011, respectively; wild-caught fishes from Fly Brook, Lefroy Brook and Shannon River, observed to be carrying what we presume to be W. inbisi inbisi glochidia have included B. porosa, N. vittata and T. bostocki47. Mature glochidia of W. inbisi inbisi have not been formally described. Reproductive phenology, age and growth have not been elucidated in W. inbisi inbisi.

Distribution: Found in southerly to south-westerly flowing freshwater streams, rivers and sometimes lakes or wetlands with water salinities less than approximately 3.0 mg/L from Boodjidup Brook in the Capes region to the west of the Blackwood River catchment to Waychinicup River within 150 km of the coast, primarily along the South Coast of Western Australia27–29,61,69 (Fig. 6).

Habitat: Similar to W. carteri although habitats can also include perched dune lakes. Waters that W. inbisi inbisi inhabit are often more tannin stained due to their occurrence in more heavily forested catchments with greater densities of native riparian vegetation than for W. carteri.

Westralunio inbisi meridiemus subsp. nov

Type material

Holotype: WAM S56235 (Fig. 7D), collected by M.W. Klunzinger.

Paratypes: WAM S56236, WAM S56237, WAM S56238, WAM S56239, collected by M. W. Klunzinger.

Type locality: Apex Weir, Margaret River, Western Australia (33.942995°S, 115.073151°E, GDA94) (see Fig. 4C).

Material examined: For W. inbisi meridiemus (= “W. carteri” III), molecular data examined included 9 and 12 individual 16S rDNA and COI mtDNA sequences, respectively, for species delimitation. Additionally, Fourier shell shape outline analysis and traditional shell morphometric measurements were examined from 12 individuals each. Complete details on all specimens examined are provided in Supplementary Table S3.

Etymology: The subspecific epithet, meridiemus, is derived from Latin ‘meridiem’, translating to ‘southwest’ in English in reference to the location of its type locality, which sits in the southwestern region of Western Australia.

Diagnosis: Specimens of W. inbisi meridiemus have five diagnostic nucleotides at COI (69 C, 123 C, 126 T, 483 A, 526 A) and none at 16S, which differentiate it from its sister taxa, W. carteri and W. inbisi inbisi using ASAP and TCS species delimitation models.

Description: This subspecies is of the ESU “W. carteri” III. Shell morphology in juveniles unknown, but adults same as W. inbisi inbisi and W. carteri as described above; total adult shell length generally < 80 mm. MHI 60–71%; anterior portion of shell with moderate development, BLI 28–35%; larger shells with abraded umbos scarcely winged; wing development variable, generally decreasing with size, BHI 84–93% (Table 2); anatomy same as W. carteri and W. inbisi inbisi, including siphon pigmentation and morphology (illustrated in Fig. 5B). Life history observations for this ESU cannot be derived from existing field observations as all known populations overlap the distribution of either W. carteri (in Margaret River) or W. inbisi inbisi (in the lower Blackwood Basin); however, mussels from those locations appear to have separate sexes based on macroscopic examinations of marsupia in both gravid and non-gravid females. Similarly, gravid female mussels have been observed from Margaret River during late spring to summer (November to December). Species of wild-caught fishes from Canebreak Pool in Margaret River that have been observed carrying glochidia include G. occidentalis and N. vittata47. Reproductive phenology, age and growth have not been elucidated in W. inbisi meridiemus.

Distribution: Found in the neighbouring catchments of Margaret River and the Blackwood River of Western Australia, where it is sympatric with W. carteri and W. inbisi inbisi, respectively27,28 (Fig. 6).

Habitat: Similar to W. carteri and W. inbisi inbisi in either lotic or lentic freshwater rivers, streams, and pools with varying degrees of riparian vegetation.

Discussion

This study is the first to integrate molecular species delimitation and morphological analyses to describe new taxa of Australian freshwater mussels. In their review of the taxonomy, phylogeography and conservation of freshwater mussels in Australasia, Walker et al.14 highlighted the need for such a taxonomic framework that uses both genetic and morphological data to gain a better understanding of species delimitation within this group. Overall, the study illustrates the value of using multiple data sources for species delimitation for cryptic taxa, provides an example when it is appropriate to recognise subspecies, and describes a case study of an IUCN listed species that would have to be re-assessed in terms of conservation status following the application of a robust taxonomic framework for recognising species boundaries.

In this study, we aimed to use multiple lines of evidence to investigate whether the three ESUs previously identified for the freshwater mussel Westralunio carteri27,28 should be recognised as separate species. Using three species delimitation models run for 164 COI mtDNA sequences, a combination of both traditional indices of shell morphology and Fourier shell shape analyses and geographical distribution records, our results provided a clear case for the recognition of at least two separate species—Westralunio carteri (Iredale, 19349) which is found in rivers draining the western coast, and W. inbisi sp. nov. which occurs in rivers draining the southern and lower southwestern coast of southwestern Australia. The recognition of these two separate species was well supported, with congruent data sets confirming that they are both morphologically and genetically divergent.

Carstens et al.70 have argued strongly that species should be delimited based on the congruence of multiple data sets that could include genetic, morphological and distributional data, as was done in this study. This is particularly true for cryptic taxa. The use of an integrated approach for resolving taxonomic uncertainties for freshwater mussels has growing support. For example, Johnson et al.4 used multiple lines of evidence to show that current taxonomy overestimated species diversity within the imperilled freshwater mussel genus Cyclonaias in North America. Similarly, Morrison et al.71 tested species boundaries in the North American Pleurobema species complex using genetic and morphological data, finding that the most likely scenario was that the two named species they investigated were members of a single, widespread species. Despite this growing trend of using multiple sources of evidence for species delimitation, several freshwater mussel taxa have been named based on shell morphology alone in recent decades. For example, the hyriids Lortiella opertanea Ponder & Bayer, 200411 and Triplodon chodo Mansur & Pimpão, 200872 were erected as new species based on shell shape indices and sculpture pattern, respectively. Molecular analysis has yet to corroborate the taxonomy in these and other recently described freshwater mussels. The propensity of shell shape to vary with the environment within freshwater mussel species can render it an often-unreliable character on which to base species taxonomy12,14,73,74. Alternatively, relying on genetic data without morphological support can also be problematic; however new species have been raised using this method2,3. While this may not be appropriate for practical purposes75,76, there is no doubt that recognising genetic differences between populations is an important aspect of describing biodiversity and indeed, has been used in several species’ concepts77,78.

Our study also provides an example where subspecies have been described in recognition of the existence of phenotypically similar, but genetically distinct evolutionary lineages within the W. carteri species complex. In our case, shell morphology for W. inbisi inbisi and W. inbisi meridiemus was mostly similar, yet these taxa possessed COI character attributes that were unique to each, largely geographically separated lineage, suggesting a degree of reproductive isolation and an evolutionarily significant process. We did have a low replicate number of shells of W. inbisi meridiemus to examine which may have accounted for the lack of statistical differences between this subspecies and W. inbisi inbisi if indeed differences might exist. While there is additional material available from Margaret and Blackwood Rivers in museum collections, we were restricted to examining only shells from which genetic information is available given Benson et al.28 found both taxa in the two river basins. The definition of a subspecies can vary but is widely accepted as an aggregate of phenotypically similar populations of a species inhabiting a geographic subdivision of the range of that species and differing taxonomically from other populations of that species79. In their study of land snails, Páll-Gergely et al.80 suggest restricting subspecies to cryptic species delimitation, for example when molecular data support lineage separation but where no clear morphological differences are currently known. We agree with this definition but caution that molecular data can exhibit differentiation related to population structure and not speciation. Fixed molecular differences are critical to confirming reciprocal monophyly when molecular phylogenetic methods are employed. The use of subspecies in the Hyriidae is relatively common. Of the 261 names available for species or subspecies of Hyriidae, 57 (21.8%) have been used either exclusively as subspecies or as either species or subspecies9,11,18,20,23,43,64,81–87. Here we recognise subspecies based on congruence in genetic and geographical differentiation but chose not to raise “W. carteri” III to species level given there was no significant difference in shell morphology between it and “W. carteri” II and because not all molecular species delimitation models revealed a separate taxon for “W. carteri” III.

These results confirm that current taxonomy underestimates species diversity of freshwater mussels in southwestern Australia and that this has implications for the listing of W. carteri as a threatened species. Freshwater mussels are amongst the most threatened aquatic species worldwide, and many authors have expressed concern about the global decline of this group88–90. It is not surprising therefore that a recent review by Benson et al.91 revealed that 44% (18 of 41 species) of described freshwater mussel species known to occur in Mediterranean-climate regions have been listed globally as either Critically Endangered, Endangered or Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. A further six species (15%) have been classified as Near Threatened. Freshwater mussels are also notorious in having shells which are morphologically plastic within the same taxa12 and taxa which have morphologically similar shells but are molecularly different, leading to ‘cryptic speciation’92. Given the increasing interest in using multiple data sets to confirm species boundaries in the group, amendments to the Red List conservation status of these listed species can be anticipated as species delimitation based originally on morphological characters is further clarified with this integrative taxonomy approach. In the case of W. carteri, the species is currently listed as ‘Vulnerable’ internationally (IUCN Red List), nationally under the Australian Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) and at the state level under the Western Australia Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. More recently, in a preliminary analysis based on past distribution data61, Klunzinger et al.27 suggested that an estimated reduction of 72% in extent of occurrence (EOO) of the W. carteri lineage identified here might qualify this species as ‘Endangered’ under criterion A2c of the IUCN Red List. More robust analyses which include recent distribution records would be needed to confirm the conservation status of this species as well as the new species described in this study. Our evidence suggests that once formal re-diagnoses and descriptions of the Westralunio taxa are published, fresh nominations for listing as threatened would be required. This would entail submission of a nomination to the Threatened Species Scientific Committee to amend the conservation status of W. carteri, and the preparation of new nominations for one or both new subspecies if deemed necessary. As more studies use an integrative approach for delineating freshwater mussel species, implications for conservation are inevitable, and this is likely to take place on a global scale. For example, the suggestion that the freshwater mussel species Pleurobema clava (listed as Endangered under the Endangered Species Act in the USA) and P. oviforme (a species being considered for listing) are members of a single, widespread species will have management implications for these species71.

Several research gaps in our knowledge of Westralunio will benefit from future investigation. The position of W. albertisi and W. flyensis from West Papua and Papua New Guinea within the genus Westralunio is unclear10,14 and employing molecular analyses will undoubtedly resolve this biogeographic and taxonomic conundrum. At a higher classification level, given that both species of juvenile Australian Westralunio have distinctive v- or w-shaped shell sculpturing on their umbos46, in combination with strongly grooved and serrated pseudocardinal hinge teeth in adult shells, calls into question their placement within the Velesunioninae defined by McMichael & Hiscock10. This is corroborated by phylogenetic data presented by Graf et al.21 and Santos-Neto et al.22 who showed Westralunio separate to the other Velesunioninae. However, until complete data are available for other Westralunio and other velesunionine species, we are reluctant to make any changes to the current arrangement of the subfamily. Also of value would be an examination of glochidia morphology and morphometry. Glochidia of W. carteri were described by Klunzinger et al.48, but the morphology and morphometry of glochidia from W. inbisi inbisi and W. inbisi meridiemus are entirely unknown and worthy of investigation. Indeed, glochidia morphology and morphometry has been shown to have taxonomic value for other species19. For example, Jones et al.93 showed divergence in larval tooth arrangement and shell size in the south-east Australian Hyridella australis (Lamarck, 181939), Hyridella depressa (Lamarck, 181939) and Cucumerunio novaehollandiae (Gray, 183494). Pimpão et al.95 were able to distinguish several species of Brazilian Hyriidae using glochidial characters and made taxonomic changes to some genera and subgenera on this basis. More recently, Melchior et al.96 presented contrasting glochidia release strategies and glochidia size in between two sympatric species of Echyridella from New Zealand, further strengthening the taxonomic division between Echyridella menziesii (Gray, 184397) and Echyridella aucklandica (Gray, 184397) recognised by Marshall et al.20.

This study has highlighted the utilisation of morphology and phylogeography to make sound decisions on drawing taxonomic boundaries between ESUs. Formalising the taxonomy of ESUs identified by Klunzinger et al.27 and Benson et al.28 for Westralunio taxa will be beneficial for conservation management of the species and subspecies identified in this study. We suggest that a similar approach of taxonomic division may be applied to other freshwater fauna of the region (and elsewhere), such as for the multiple lineages of pygmy perches or galaxiid fishes alluded to by Morgan et al.98 and Buckley et al.99. Furthermore, the taxonomic approach illustrated in our study should be applied to other as yet undescribed ‘cryptic species’ of Australian freshwater mussels92,100,101 as a way forward in resolving taxonomic uncertainty within the group.

Methods

Mapping and provenance

River basins within the South West Coast Drainage Division of Australia as defined under AWRC102. Spatial data were mapped as vector data in QGIS Desktop 3.24.3 (https://qgis.org/en/site/) using the GCS_GDA_1994 coordinate system103. The country outline for Australia was drawn from the GADM database (www.gadm.org), version 2.0, December 2011 under license. The rivers were mapped from the Linear (Hierarchy) Hydrography of Western Australia dataset (https://catalogue.data.wa.gov.au/dataset/hydrography-linear-hierarchy/resource/9908c7d1-7160-4cfa-884d-c5f631185859), under license.

Gross anatomy

Siphon characters, which are not easily examined in preserved specimens (for example, due to tissue contraction and discolouration), were observed in live specimens of W. carteri in the Canning and Margaret Rivers with mask and snorkel and photographed in their natural state with a waterproof digital camera. Tissue anatomy of freshly dead and preserved specimens was examined employing well-established dissection methods10 on specimens collected for data published by Klunzinger et al.27. For shell sculpture examination, we drew on data published by Zieritz et al.46. Individual specimens of dry shells lacking soft anatomy, also examined for shell shape and measured morphometrically (see below) were examined for the arrangement of adductor and retractor muscle scars following McMichael & Hiscock10.

Genetic methods

Sequence alignment construction

We assembled mitochondrial Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit I (COI) and 16S rDNA (16S) gene sequences originally published by Klunzinger et al.27 and Benson et al.28. Available nuclear gene sequences (18S and 28S rDNA) were not used in our analysis because they have insufficient variation to be informative28. Sequences were retrieved from GenBank, along with sequences for two other Hyriid species for use as outgroups (Velesunioninae: Velesunio ambiguous (Philippi, 184726) and Hyriinae: Hyridellini: Cucumerunio novaehollandiae (Gray, 183494)) (see Table 3). We limited the outgroup species to two hyriids in our tree because of the extreme divergence of W. carteri, even from other Hyriidae (see Graf et al.21). Individual alignments for both genes were built using the ClustalW accessory application in Bioedit 7.2.5104, before inspecting and trimming to equal length in MEGA X version 10.1.8105.

Table 3.

Taxa used for phylogenetic analyses.

| BASIN/Locality | Waterbody | Taxon/ESU | COI | 16S | Voucher/source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MANNING, NSW, Australia | Glochester River | Cucumerunio novaehollandiae | KP184901 | KP184853 | UMMZ 30450121 |

| HAWKSBURY, NSW, Australia | Napean River | Velesunio ambiguus | KP184915 | KP184868 | FMNH 33719521 |

| MOORE-HILL, WA, Australia | Gingin Brook | “Westralunio carteri” I | MT040666 | – | WAM S8279127 |

| SWAN COAST, WA, Australia | Lake Leschenaultia | “Westralunio carteri” I |

WAM S8273927 UMMZ 30451727 |

||

| SWAN COAST, WA, Australia | Marbling Brook | “Westralunio carteri” I | MT040671 | – | WAM S8279027 |

| SWAN COAST, WA, Australia | Neerigen Brook | “Westralunio carteri” I | KP184917 | KP184870 | UMMZ 30451627 |

| SWAN COAST, WA, Australia | Wungong Brook | “Westralunio carteri” I |

– – - |

||

| MURRAY, WA, Australia | Serpentine River | “Westralunio carteri” I |

– – – – – |

WAM S5622327 WAM S8277927 |

|

| COLLIE, WA, Australia | Collie River | “Westralunio carteri” I |

– – – – – |

WAM S5621027 WAM S8277727 |

|

| PRESTON, WA, Australia | Preston River | “Westralunio carteri” I |

– – – – – |

WAM S5621627 WAM S5621727 |

|

| BUSSELTON COAST, WA, Australia | Capel River | “Westralunio carteri” I |

WAM S11270528 WAM S11270628 WAM S11270728 WAM S11270828 WAM S11270928 |

||

| BUSSELTON COAST, WA, Australia | Ludlow River | “Westralunio carteri” I |

WAM S11271028 WAM S11271128 WAM S11271228 WAM S11271328 WAM S11271428 |

||

| BUSSELTON COAST, WA, Australia | Abba River | “Westralunio carteri” I |

WAM S11271528 WAM S11271628 WAM S11271728 WAM S11271828 WAM S11271928 |

||

| BUSSELTON COAST, WA, Australia | Carbanup River | “Westralunio carteri” I |

WAM S11272028 WAM S11272128 WAM S11272228 WAM S11272328 WAM S11272428 |

||

| BUSSELTON COAST, WA, Australia | Ellens Brook | “Westralunio carteri” I |

WAM S11273028 WAM S11273128 WAM S11273228 WAM S11273328 WAM S11273428 |

||

| BUSSELTON COAST, WA, Australia | Wilyabrup Brook | “Westralunio carteri” I |

WAM S11272528 WAM S11272628 WAM S11272728 WAM S11272828 WAM S11272928 |

||

| BUSSELTON COAST, WA, Australia | Boodjidup Brook |

“Westralunio carteri” I “ “ “ “Westralunio carteri” II |

WAM S11279028 WAM S11279128 WAM S11279228 WAM S11279328 WAM S11279428 |

||

| BUSSELTON COAST, WA, Australia | Margaret River |

“Westralunio carteri” III “ “ “ “ “Westralunio carteri” I “Westralunio carteri” III “Westralunio carteri” I “Westralunio carteri” III “ |

– – – |

WAM S11273528 WAM S11273628 WAM S11273728 WAM S11273828 WAM S11273928 |

|

| BLACKWOOD, WA, Australia | Scott River |

“Westralunio carteri” II “ “ “Westralunio carteri” III “Westralunio carteri” II |

WAM S11274028 WAM S11274128 WAM S11274228 WAM S11274328 WAM S11274428 |

||

| BLACKWOOD, WA, Australia | Chapman River |

“Westralunio carteri” III “Westralunio carteri” II “ “ “Westralunio carteri” III |

WAM S11278528 WAM S11278628 WAM S11278728 WAM S11278828 WAM S11278928 |

||

| BLACKWOOD, WA, Australia | St. Johns Brook |

“Westralunio carteri” II “ “ “ “ “ “Westralunio carteri” III “Westralunio carteri” II |

– – |

WAM S8277327 WAM S6616527 WAM S11281028 WAM S11281128 WAM S11281228 WAM S11281328 WAM S11281428 |

|

| DONNELLY, WA, Australia | Donnelly River | “Westralunio carteri” II |

WAM S11278028 WAM S11278128 WAM S11278228 WAM S11278328 WAM S11278428 |

||

| WARREN, WA, Australia | Lake Yeagarup | “Westralunio carteri” II |

WAM S11277528 WAM S11277628 WAM S11277728 WAM S11277828 WAM S11277928 |

||

| WARREN, WA, Australia | Warren River | “Westralunio carteri” II |

WAM S11274528 WAM S11274628 WAM S11274728 WAM S11274828 WAM S11274928 |

||

| SHANNON, WA, Australia | Gardner River | “Westralunio carteri” II |

WAM S11275028 WAM S11275128 WAM S11275228 WAM S11275328 WAM S11275428 |

||

| SHANNON, WA, Australia | Shannon River | “Westralunio carteri” II |

WAM S11275528 WAM S11275628 WAM S11275728 WAM S11275828 WAM S11275928 |

||

| SHANNON, WA, Australia | Inlet River | “Westralunio carteri” II |

WAM S11279528 WAM S11279628 WAM S11279728 WAM S11279828 WAM S11279928 |

||

| SHANNON, WA, Australia | Deep River | “Westralunio carteri” II |

WAM S11276028 WAM S11276128 WAM S11276228 WAM S11276328 WAM S11276428 |

||

| SHANNON, WA, Australia | Walpole River | “Westralunio carteri” II |

WAM S11280028 WAM S11280128 WAM S11280228 WAM S11280328 WAM S11280428 |

||

| KENT COAST, WA, Australia | Bow River | “Westralunio carteri” II |

WAM S11276528 WAM S11276628 WAM S11276728 WAM S11276828 WAM S11276928 |

||

| KENT COAST, WA, Australia | Kent River | “Westralunio carteri” II |

– – – – – |

WAM S82758.127 WAM S82758.227 WAM S11277028 WAM S11277128 WAM S11277228 WAM S11277328 WAM S11277428 |

|

| DENMARK COAST, WA, Australia | Marbellup Brook | “Westralunio carteri” II |

WAM S11281528 WAM S11281628 WAM S11281728 WAM S11281828 WAM S11281928 |

||

| ALBANY COAST, WA, Australia | Goodga River | “Westralunio carteri” II |

– – – – |

WAM S11270028 WAM S11270128 WAM S11270228 WAM S11270328 WAM S11270428 |

|

| ALBANY COAST, WA, Australia | Waychinicup River | “Westralunio carteri” II |

WAM S6612727 WAM S6612827 WAM S11280528 WAM S11280628 WAM S11280728 WAM S11280828 WAM S11280928 |

Specimen provenance, GenBank accession numbers for mitochondrial Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit I (COI) and 16S rDNA (16S) gene sequences, and voucher codes (in reference to source publications) are provided. Institution codes: FMNH Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois, USA; UMMZ University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA; WAM Western Australian Museum, Welshpool, Western Australia, Australia. ESU Evolutionary Significant Unit, NSW New South Wales, WA Western Australia.

Phylogenetic analyses and species delimitation

The COI alignment, including outgroups, was reduced to unique haplotypes using DnaSP v6106. Individual haplotype names correspond to those used in Benson et al.28. The alignment was partitioned by codon position in Mesquite version 3.61107, and the best fitting substitution model for each partition was identified by jModelTest108. This alignment was then used to construct Maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) trees in W-IQ-TREE109 and MrBayes version 3.2.7a110 respectively. The ML analysis was performed with 10,000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates using the standard settings of the selected substitution models. The BI analysis was performed with two independent runs of 1 × 107 generations sampling every 500 generations to achieve an average standard deviation of the split frequencies that was consistently < 0.01, and ESS values > 200. Convergence of the MCMC chains was also confirmed in Tracer version 1.7.1111. In order to determine the number of distinct taxa within W. carteri, three methods of species delimitation were applied to the COI dataset, excluding outgroups. Firstly, the distance-based method, Assemble Species by Automatic Partitioning (ASAP)112, was implemented using the Jukes-Cantor (JC69) option on the online webserver (https://bioinfo.mnhn.fr/abi/public/asap/). Secondly, a statistical parsimony method was run in TCS 1.21113 using a 95% connection limit. Finally, the BI tree was assessed using Bayesian implementation of the Poisson Tree Process (bPTP)114 on the bPTP webserver (https://species.h-its.org/ptp/) with the maximum allowable number of MCMC generations (5 × 105) and 20% burn-in. The ML and BI trees were edited in FigTree v1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/) and Inkscape v1 (https://inkscape.org).

Molecular diagnosis

For the molecular diagnosis of taxa within W. carteri we considered fixed nucleotide differences found within the alignments of the full dataset for each gene (i.e., character attributes that were present in all individuals of one taxon while being absent in all individuals of the other two taxa115–117. For each gene, these characters were identified using the ‘toggle conserved sites’ option in MEGA X 10.1.8105. The uncorrected p-distance (mean and SE) to the nearest neighbour of each taxon was determined in the same software.

Shell measurements

Shells were measured to the nearest 0.1 mm using manual callipers or, for photographed specimens, to the nearest 0.5 mm using a ruler as a scale bar appearing in each photograph. Shells utilised for Fourier shape analysis (see below) from photos provided by Graf & Cummings63 were not measured because scales were not included in the photos. For shell morphometry, we followed measurement procedures defined by McMichael & Hiscock10 (Fig. 8): total length (TL), measured as the horizontal distance from the anterior apex to the posterior apex of the valve; maximum height (MH), measured as the vertical distance from the ventral edge to the point of the beak; beak height (BH), measured from the point of the beak to the ventral margin; beak length (BL), measured as the horizontal distance from the anterior apex to the imaginary line perpendicular to the apex of the beak.

Morphometric analysis

We conducted traditional morphometric analysis and outline (Fourier shape) analysis to assess whether shell shapes are different for each of the Westralunio ESUs identified27,28. Details of specimens used in these two analyses are provided in the ‘material examined’ sections below. Geographic distribution of these samples is illustrated in Fig. 6. A total of 446 and 411 specimens were included in traditional and Fourier shape analysis, respectively: 294 and 273 “W. carteri” I, respectively; 140 and 126 “W. carteri” II, respectively; and 12 and 12 “W. carteri” III, respectively.

Like Ponder & Bayer11 and Sheldon101, we tested for differences in shell measurements and sagittal shell shape between the two species and among the three taxa, respectively. ‘Traditional’ shell shape indices10 were calculated from shell measurements for maximum height index (MHI), beak height index (BHI), and beak length index (BLI), such that: ; ; . Firstly, significant differences in TL, MH, BH, BL, MHI, BHI and BLI, respectively, were tested for using ANOVAs followed by pairwise Tukey’s posthoc comparisons. Secondly, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on these variables was performed, following ANOVAs and Tukey’s posthoc comparisons on the first two PC-axes. Thirdly, we employed Discriminant Analysis (DA) to assess the proportion of specimens that would be assigned to the correct taxa based on these shell indices.

Overall shell shape was analysed using Fourier shape analysis118. This method breaks information on sagittal shell outlines of specimens into a set number of harmonics, each of which is explained by two Fourier coefficients, which are then analysed statistically. Specimens held in the Western Australian Museum collections were photographed using a Canon EOS 3D digital camera. A photographic stand was set up to hold the camera at the same distance, angle and focus for each photographed specimen. Black felt was used as a background medium to minimise shadows in the photos and a silver ruler was included in each photo in the same position as a scale bar. Additional digital photos of shell specimens from other museum collections were obtained, with permission, from the Mussel Project website63.

Shell outlines of specimens were digitised into xy-coordinates using the program IMAGEJ119. The digitised outlines were then subjected to Fast Fourier transformation using the program HANGLE, applying a smoothing normalisation of 20 to eliminate high frequency pixel noise. Preliminary analysis indicated that the first 10 harmonics described the outlines with sufficiently high precision. Discarding of the first harmonic, which did not contain any shape information, resulted in a set of 18 Fourier coefficients per individual. After rotating outlines to maximum overlap with program HTREE, a PCA was performed on the 18 Fourier coefficients using program PAST120. Synthetic outlines of extreme shell forms were drawn using program HCURVE118.

To test for statistical differences in overall sagittal shell shape between the two species (W. carteri and W. inbisi), we conducted t-tests on the first two PC-axes and carried out an analysis of similarities (ANOSIM; 9,999 permutations, Euclidean distance) and DA on the set of 18 Fourier coefficients. The degree of shell inflation (relative shell width) was not considered because, in contrast to sagittal shell shape, this morphological character is strongly influenced by ontogenetic growth in Unionida14,73. Statistical analyses were conducted in PAST 3.22121 (PCAs, DAs, ANOSIM), and R version 3.6.3 (ANOVAs and Tukey’s post hoc comparisons).

Nomenclatural acts

The electronic edition of this article conforms to the requirements of the amended ICZN44.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Funding support for publication costs of this study was provided by the University of Western Australia and the Western Australian Museum. We thank the editors and three anonymous reviewers for helpful suggestions and feedback which greatly improved the quality of our publication. We thank Dr Mandy Reid and staff in the Malacology Section at the Australian Museum, Sydney for providing type specimen photos of Westralunio ambiguus carteri Iredale, 1934 and Dr Stephen J. Beatty, Murdoch University, for providing the photo of the Goodga River type locality for Westralunio inbisi inbisi. We thank Associate Professor Daniel Graf for providing images of freshwater mussels from The Mussel Project for use in this study (cited as Graf & Cummings, 2018). We especially thank Associate Professor Alan J. Lymbery for collecting numerous specimens used in this study and WA Museum Research Associate Alan Longbottom for his assistance in registering new voucher specimen material used in this study. We acknowledge the Western Australian Museum Aboriginal Advisory Committee (WAMAAC), and especially Deanne Fitzgerald, Senior Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advisor, for guidance and support in the selection of a culturally specific name for the new species. We acknowledge invaluable efforts collectors and curators have endured over many years to provide a library of specimens which made this study possible.

Abbreviations

- AMS

The Australian Museum, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Bk

Brook

- BMNH

The Natural History Museum, London, UK

- FMNH

Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL, USA

- ICZN

International Code for Zoological Nomenclature

- Lk

Lake

- MCZ

Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA

- MU

Murdoch University, Murdoch, WA, Australia

- R

River

- Res

Reservoir

- UMCZ

University Museum of Zoology Cambridge, UK

- UMMZ

University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

- WAM

Western Australian Museum, Perth, WA, Australia

Author contributions

All authors contributed to writing the main manuscript text. M.K., J.B. and A.Z. wrote the Methods. J.B. analysed genetic data. M.K. measured shells. M.K. and C.W. photographed specimens. A.Z. analysed specimen photos for Fourier shape analyses. M.K. and A.Z. analysed shell measurement data. C.W. registered specimens, collated type series data and checked taxonomic authorities and nomenclatural acts. B.S., J.B. and M.K. prepared Fig. 1. A.Z. prepared Fig. 2. M.K. prepared Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8. M.K. and J.B. prepared Tables 1 and 2. A.Z. and M.K. prepared Table 3. J.B. and M.K. prepared supplementary data. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Data availability

Spatial data for mapping are provided in the Methods section. Data for specimen records we examined for this study (Tables 3, S1, S2 and S3) are available online. Those held at the Western Australian Museum Collection and Research Centre, Perth, WA, Australia (WAM) and the Australian Museum, Sydney, NSW, Australia are available from the Online Zoological Catalogue of Australian Museums (OZCAM) at https://ozcam.org.au/ and the Atlas of Living Australia (ALA) at https://www.ala.org.au/. Additional specimen records are available from the Mussel Project Website (Musselp) at https://mussel-project.uwsp.edu/index.html and individual museum collections as follows—University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, Ann Arbor, MI, USA (UMMZ): https://fms02.lsa.umich.edu/fmi/webd/ummz_mollusks; Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL, USA (FMNH): https://www.fieldmuseum.org/science/research/area/invertebrates; The Natural History Museum, London, UK (BMNH): https://data.nhm.ac.uk/search#; Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA (MCZ): https://mcz.harvard.edu/malacology-research-collection. The genetic sequences utilised for this study (Tables 3, S1, S2 and S3) are available from GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/?term=Westralunio+carteri). The dataset generated in this study is also available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors in Figure 4 and Table 3. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

8/22/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-023-40483-0

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-24767-5.

References

- 1.Bickford D, et al. Cryptic species as a window on diversity and conservation. Trends. Ecol. Evol. 2007;22:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolotov IN, et al. New taxa of freshwater mussels (Unionidae) from a species-rich but overlooked evolutionary hotspot in Southeast Asia. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:11573. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11957-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolotov IN, et al. Eight new freshwater mussels (Unionidae) from tropical Asia. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:12053. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48528-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson NA, et al. Integrative taxonomy resolves taxonomic uncertainty for freshwater mussels being considered for protection under the U.S. endangered species act. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:15892. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33806-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopes-Lima M, et al. Expansion and systematics redefinition of the most threatened freshwater mussel family, the Margaritiferidae. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2018;127:98–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2018.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopes-Lima M, et al. Freshwater mussels (Bivalvia: Unionidae) from the rising sun (Far East Asia): phylogeny, systematics, and distribution. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2020;146:106755. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2020.106755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konopleva ES, et al. A new genus and two new species of freshwater mussels (Unionidae) from western Indochina. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(4106):1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39365-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith CH, Johnson NA, Inoue K, Doyle RD, Randklev CR. Integrative taxonomy reveals a new species of freshwater mussel, Potamilus streckersoni sp. nov. (Bivalvia: Unionidae): implications for conservation and management. Syst. Biodiv. 2019;17:331–348. doi: 10.1080/14772000.2019.1607615. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iredale T. The freshwater mussels of Australia. Aust. Zool. 1934;8:57–78. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMichael DF, Hiscock ID. A monograph of the freshwater mussels (Mollusca: Pelecypoda) of the Australian Region. Aust. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1958;9:372–507. doi: 10.1071/MF9580372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ponder WF, Bayer M. A new species of Lortiella (Mollusca: Bivalvia: Unionoidea: Hyriidae) from northern Australia. Molluscan Res. 2004;24:89–102. doi: 10.1071/MR04007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balla SA, Walker KF. Shape variation in the Australian freshwater mussel Alathyria jacksoni Iredale (Bivalvia, Hyriidae) Hydrobiologia. 1991;220:89–98. doi: 10.1007/BF00006541. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mock KF, et al. Genetic structuring in the freshwater mussel Anodonta corresponds with major hydrologic basins in the western United States. Mol. Ecol. 2010;19:569–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker KF, Jones HA, Klunzinger MW. Bivalves in a bottleneck: Taxonomy, phylogeography and conservation of freshwater mussels (Bivalvia: Unionoida) in Australasia. Hydrobiologia. 2014;735:61–79. doi: 10.1007/s10750-013-1522-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams JD, et al. A revised list of the freshwater mussels (Mollusca: Bivalvia: Unionida) of the United States and Canada. Freshw. Mol. Biol. Conserv. 2017;20:33–59. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graf DL, Cummings KS. A ‘big data’ approach to global freshwater mussel diversity (Bivalvia: Unionoida), with an updated checklist of genera and species. J. Mollus. Stud. 2021;87:034. doi: 10.1093/mollus/eyaa034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graf DL, Cummings KS. Palaeoheterodont diversity (Mollusca: Trigonoida + Unionoida): What we know and what we wish we knew about freshwater mussel evolution. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. Lond. 2006;148:343–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2006.00259.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graf DL, Cummings KS. Review of the systematics and global diversity of freshwater mussel species (Bivalvia: Unionoida) J. Mollus. Stud. 2007;73:291–314. doi: 10.1093/mollus/eym029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauer G, Wächtler K. Ecology and Evolution of the Freshwater Mussels Unionoida. Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marshall BA, Fenwick MC, Ritchie PA. New Zealand recent Hyriidae (Mollusca: Bivalvia: Unionida) Molluscan Res. 2014;34:181–200. doi: 10.1080/13235818.2014.889591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graf DL, Jones HA, Geneva AJ, Pfeiffer JM, III, Klunzinger MW. Molecular phylogenetic analysis supports a Gondwanan origin of the Hyriidae (Mollusca: Bivalvia: Unionida) and the paraphyly of Australasian taxa. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2015;85:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santos-Neto GC, et al. Genetic relationships among freshwater mussel species from fifteen Amazonian rivers and inferences on the evolution of the Hyriidae (Mollusca: Bivalvia: Unionida) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2016;100:148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyahira IC, Dos Santos SB, Mansur MCD. Freshwater mussels from South America: State of the art of Unionida, specially Rhipidodontini. Biota Neotrop. 2017;17:e20170341. doi: 10.1590/1676-0611-bn-2017-0341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tapparone Canefri C. Fauna malacologica della Nuova Guinea e delle isole adiaoenti. Ann. Mus. Civ. Stor. Nat. Genova. 1883;19:6–313. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clench W. Two new land and freshwater mollusks from New Guinea. Breviora. 1957;6:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Philippi, R. A. Abbildungen und Beschreibungen neuer oder wenig gekaunter Conchylien. Vol. 3, Unio. (Cassel, 1845–1851).

- 27.Klunzinger MW, et al. Phylogeographic study of the West Australian freshwater mussel, Westralunio carteri, uncovers evolutionarily significant units that raise new conservation concerns. Hydrobiologia. 2021;848:2951–2964. doi: 10.1007/s10750-020-04200-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benson J, Stewart BA, Close PG, Lymbery AJ. Evidence for multiple refugia and hotspots of genetic diversity for Westralunio carteri, a threatened freshwater mussel in south-western Australia. Aquat. Conserv. 2022;32:559–575. doi: 10.1002/aqc.3780. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klunzinger MW, et al. Distribution of Westralunio carteri Iredale, 1934 (Bivalvia: Unionoida: Hyriidae) on the south coast of south-western Australia, including new records of the species. J. R. Soc. West. Aust. 2012;95:77–81. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coates DJ, Byrne M, Moritz C. Genetic diversity and conservation units: Dealing with the species-population continuum in the age of genomics. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018;6:165. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2018.00165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linnaeus, C. Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, cum Characteribus, (Differentiis, Synonymis, locis 1: 823, emendanda, 1758).

- 32.Grobben K. Zur kenntnis der morphologie, der verwandtschaftsverhältnisse und des systems der mollusken. Sitzung. Kaiserl. Akad. Wissenschaften. Math. Nat. Classe. 1894;103:61–86. [Google Scholar]