Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns worldwide forced children and adolescents to change and adapt their lives to an unprecedented situation. Using an online survey, we investigated whether they showed changes in sleep quality and other related factors due to this event. Between February 21st, 2021 and April 19th, 2021, a total of 2,290 Austrian children and adolescents (6–18 years) reported their sleep habits and quality of sleep as well as physical activity, daylight exposure and usage of media devices during and, retrospectively, before the pandemic. Results showed an overall delay of sleep and wake times. Almost twice as many respondents reported having sleeping problems during the pandemic as compared to before, with insomnia, nightmares and daytime sleepiness being the most prevalent problems. Furthermore, sleeping problems and poor quality of sleep correlated positively with COVID-19 related anxiety. Lastly, results showed a change from regular to irregular bedtimes during COVID-19, higher napping rates, a strong to very strong decrease in physical activity and daylight exposure, as well as a high to very high increase in media consumption. We conclude that the increase in sleeping problems in children and adolescent during COVID-19 is concerning. Thus, health promoting measures and programs should be implemented and enforced.

Subject terms: Circadian rhythms and sleep, Paediatric research, Psychology, Human behaviour

Introduction

Sleep is an important factor for our general well-being. Healthy sleep aids the regulation of behavior, emotions, and stress1,2. Sleep problems on the other hand can negatively affect these domains and are also likely to have an impact on cognition, physical health, and academic performance3. Due to rapid developmental changes (e.g., cortical reorganization processes in the maturing brain), children and adolescents are at heightened risk for the onset of sleep and mental health issues4,5. In fact, it has been shown that sleeping problems in children and adolescents are linked to behavioral (e.g., self-regulation, conduct, attention) and emotional (e.g., depression, anxiety, stress) problems6–8. Furthermore, longitudinal studies indicate that sleeping problems during childhood and adolescence heighten the risk for the development of psychopathology—particularly anxiety and depression disorders9–12, but also attention problems and aggression7—later in life. Thus, promoting and maintaining an optimal quality of sleep during this vulnerable phase of life seems to be of special importance.

The COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns worldwide forced people to change and adapt their lives to an unprecedented situation. Since most activities that typically occupy youths’ lives have been highly restricted (e.g., in-person teaching, community-based and leisure activities, socializing with peers), children and adolescents may be especially affected by anti-COVID-19 measures13,14. Thus, the pandemic and the implemented restrictions can have serious consequences on emotional and physical well-being as well as on sleep15,16. For example, having to cope with major changes in routines (e.g., shift in the regularity of daily schedules; homeschooling) and worrying about one’s own or the health of others likely causes a lot of stress and anxiety14,17. Via increased arousal levels or vigilance, this may lead to difficulties falling asleep or to an increase in the number of nocturnal awakenings, thereby shortening sleep and lowering its quality18,19. Additionally, the circadian sleep drive may be lower after spending less time under natural sunlight and fresh air, thus possibly delaying sleep onset20. A reduction in physical activity and weight gains due to long phases of home confinement may also have a negative impact on sleep quality and well-being21,22. Furthermore, the use of screen-based media devices emitting high amounts of blue light close to bedtime may suppress melatonin secretion and the contents (e.g., social media, news, movies) consumed via those devices can make falling asleep more difficult23.

Thus, the potential for sleeping problems to emerge or worsen during this challenging period is high. The majority of studies and surveys regarding sleep in children and adolescents (especially in the age range between 6 and 14 years) during COVID-19 seem to be parent-reported24. However, research suggests that the validity of reports is higher when individuals report their own perceptions. This has also been shown for sleep-related measures (e.g., sleep quality and duration, sleep timing) in children and adolescents25–27. Self-reported data can facilitate the understanding of internal experiences, e.g., regarding well-being, health and emotions and have been shown to be sufficiently reliable in children from about 6 years of age and onwards28,29.

Hence, we designed a self-reported online survey that aimed at assessing whether and to which extent children and adolescents (6–18 years) subjectively perceived changes in their sleep patterns and behavior during COIVD-19 compared to before. The survey included questions regarding changes in bed- and wake times (e.g., due to changes in daily structure), changes in sleep quality as well as in the frequency, duration, and burden of sleeping problems (e.g., due to anxiety related to COVID-19). Furthermore, additional factors (e.g., restriction of outdoor activities) that could have affected their sleep during COVID-19 were assessed.

Results

The complete results (descriptive and statistics) can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Demographic data

Out of 5483 participants17,30, 2565 participants continued with the sleep part of the survey. Since 275 participants aborted before completing the survey, the final sample consisted of 2290 participants: 1439 females (62.8%), 818 males (35.7%) and 33 diverse (1.4%) with the following age distribution: 6–10 years 375 (16.4%), 11–14 years 962 (42.0%), and 15–18 years 953 (41.6%). Descriptive statistics of the sample are reported in Table 1. Please note that due to the small sample size of participants identifying as diverse, only participants identifying as female and male were considered for further analyses.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants.

| Response option | 6–10 years | 11–14 years | 15–18 years | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | N | % | 95% CI | n | N | % | 95% CI | n | N | % | 95% CI | ||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||||||||

| Sex | |||||||||||||||

| Male | 188 | 375 | 50.1 | 44.96 | 55.31 | 376 | 952 | 39.5 | 36.38 | 42.68 | 254 | 930 | 27.3 | 24.47 | 30.30 |

| Female | 187 | 375 | 49.9 | 44.69 | 55.04 | 576 | 952 | 60.5 | 57.32 | 63.63 | 676 | 930 | 72.7 | 69.70 | 75.53 |

| In which state do you live? | |||||||||||||||

| Burgenland | 5 | 375 | 1.3 | 0.43 | 3.08 | 21 | 952 | 2.2 | 1.37 | 3.35 | 20 | 930 | 2.2 | 1.32 | 3.30 |

| Carinthia | 18 | 375 | 4.8 | 2.87 | 7.48 | 33 | 952 | 3.5 | 2.40 | 4.83 | 13 | 930 | 1.4 | 0.75 | 2.38 |

| Lower Austria | 39 | 375 | 10.4 | 7.50 | 13.94 | 85 | 952 | 8.9 | 7.19 | 10.92 | 140 | 930 | 15.1 | 12.82 | 17.52 |

| Upper Austria | 40 | 375 | 10.7 | 7.73 | 14.24 | 90 | 952 | 9.5 | 7.67 | 11.49 | 96 | 930 | 10.3 | 8.44 | 12.46 |

| Salzburg | 59 | 375 | 15.7 | 12.20 | 19.82 | 145 | 952 | 15.2 | 13.01 | 17.67 | 173 | 930 | 18.6 | 16.15 | 21.26 |

| Styria | 104 | 375 | 27.7 | 23.26 | 32.56 | 331 | 952 | 34.8 | 31.74 | 37.89 | 259 | 930 | 27.8 | 24.99 | 30.85 |

| Tyrol | 14 | 375 | 3.7 | 2.06 | 6.18 | 33 | 952 | 3.5 | 2.40 | 4.83 | 38 | 930 | 4.1 | 2.91 | 5.57 |

| Vorarlberg | 13 | 375 | 3.5 | 1.86 | 5.86 | 22 | 952 | 2.3 | 1.45 | 3.48 | 28 | 930 | 3.0 | 2.01 | 4.32 |

| Vienna | 83 | 375 | 22.1 | 18.03 | 26.68 | 192 | 952 | 20.2 | 17.66 | 22.86 | 163 | 930 | 17.5 | 15.14 | 20.13 |

| What school are you attending? | |||||||||||||||

| Elementary school: Volksschule | 373 | 375 | 99.5 | 98.09 | 99.94 | ||||||||||

| School for people with special needs | 2 | 375 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 1.91 | 5 | 952 | 0.5 | 0.17 | 1.22 | 3 | 930 | 38.0 | 34.83 | 41.16 |

| Midldle school: AHS Unterstufe | 250 | 952 | 26.3 | 23.49 | 29.18 | 8 | 930 | 0.9 | 0.37 | 1.69 | |||||

| Middle school: Gymnasium | 243 | 952 | 25.5 | 22.78 | 28.42 | 63 | 930 | 41.0 | 37.79 | 44.21 | |||||

| Middle school: Neue Mittelschule | 382 | 952 | 40.1 | 37.00 | 43.32 | 30 | 930 | 2.4 | 1.49 | 3.56 | |||||

| High school: BHS (HTL, HAK, HLW, BAFEP) | 26 | 952 | 2.7 | 1.79 | 3.98 | 381 | 930 | 5.3 | 3.92 | 6.91 | |||||

| High school: BMS (Fachschule, Handelsschule) | 4 | 952 | 0.4 | 0.12 | 1.07 | 22 | 930 | 6.8 | 5.24 | 8.58 | |||||

| High school: Berufsschule und Lehre | 2 | 952 | 0.2 | 0.03 | 0.76 | 49 | 930 | 3.2 | 2.19 | 4.57 | |||||

| High school: AHS Oberstufe | 34 | 952 | 3.6 | 2.49 | 4.96 | 353 | 930 | 2.3 | 1.40 | 3.43 | |||||

| High school: Polytechnische Schule | 6 | 952 | 0.6 | 0.23 | 1.37 | 21 | 930 | 0.3 | 0.07 | 0.94 | |||||

CI, 95% confidence interval with lower and upper border; empty spaces response option was not chosen in this age group.

Bed- and wake times

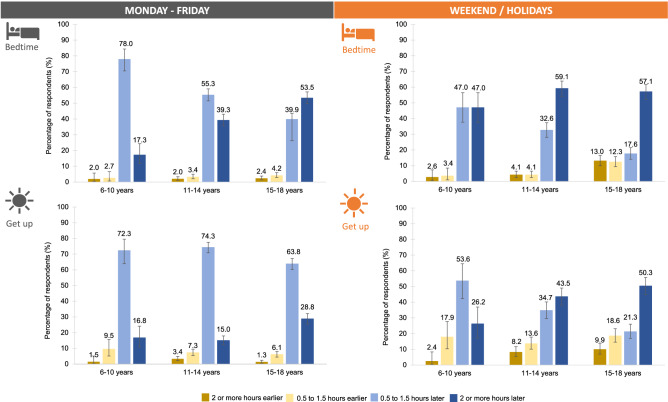

On average, 63% reported a change in bed- and wake times during the week. Regarding the weekend, only 41% reported a change in bedtimes and 31% in wake times. Overall, 6–10-year-olds always reported significantly smaller changes than 11–14- and/or 15–18-year-olds (Table S2). With reference to the direction of change, there was a strong delay in bed- and wake times in all age groups (Fig. 1, Table S1). Especially during the week, 15–18-year-olds reported significantly later bedtimes and wake times than 6–10-year and 11–14-year-olds (Table S2).

Figure 1.

Changes in sleep rhythm. Delay in bed- and wake times in children and adolescents during COVID-19 compared to before. During the week as well as on weekends (more pronounced), children and adolescents reported later bedtimes. However, wake times, especially at weekdays, were not delayed to the same extent as bedtimes. Additionally, the delay in bed- and wake times increased with age, i.e., 15–18-year-olds reported the strongest delays.

Among the 6–10-year-olds, the delay mainly ranged within 0.5 to 1.5 h and increased further with age– for example, 57% of the 15–18-year-old reported going to bed 2 or more hours later on weekends. However, wake times, particularly during the week, were not delayed to the same extent as bedtimes (e.g., 11–14 years: bedtime 2 or more hours later: 39.7%; wake time 2 or more hours later: 15.0%; difference of 24.7 percentage points).

11–14-year-old females went to bed significantly later during the week and on weekends while 15–18 year-old males went to bed and tended to get up later on weekends than their female counterparts (Table S3).

General sleep quality, sleeping problems and COVID-19 related anxiety

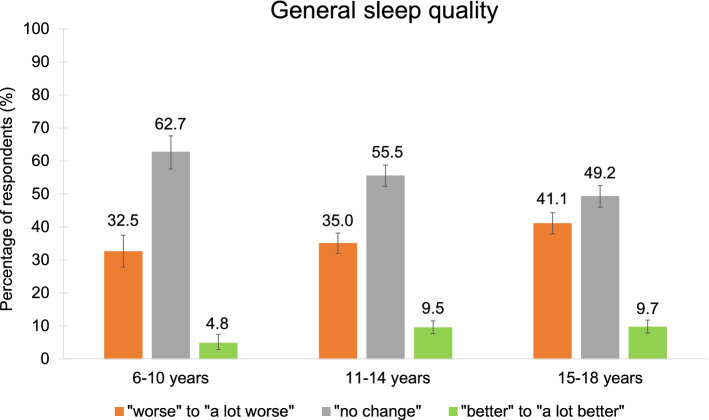

On average, 56% of the participants noticed a change in general sleep quality with most of them sleeping “worse” or “a lot worse” than before the pandemic (Fig. 2, Table S4). Overall, females rated their sleep quality worse than males (Table S6).

Figure 2.

Change in general sleep quality. Around one third of children and adolescents reported to sleep “worse” or “a lot worse” while more than half of the participants experienced “no change” in their quality of sleep compared to before the pandemic.

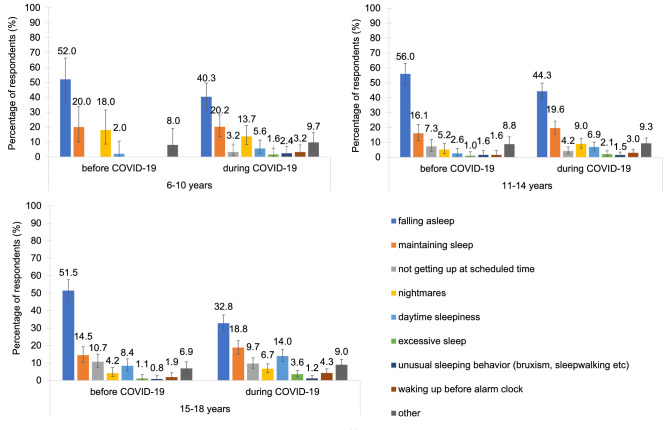

Before COVID-19, the youngest participants (6–10 years) reported the least sleeping problems (13.3%), followed by the 11–14-year-olds (20.3%) and the 15–18-year-olds (28.2%). Across all age groups, difficulties falling asleep and maintaining sleep were the most common (Fig. 3). In the 6–10-year-olds, nightmares were also relatively common. In the 11–14-year-olds and 15–18-year-olds, difficulties getting up at the scheduled time and daytime sleepiness were the third and fourth common sleeping difficulties. Regarding the duration of sleeping problems, all age groups showed a similar pattern of roughly one third having the problems for the duration of 0–6 months, between 6 months and 2 years, or between 2 and more than 5 years (Table S4). In terms of burden, 6–10-year-olds mainly reported their sleeping difficulties as being a little burdensome or moderately to severely burdensome while the majority of the 11–18-year-olds perceived them as moderately to severely burdensome (Table S4).

Figure 3.

Types of sleeping problems. The distribution of types of sleeping problems in children and adolescents was similar before and during the pandemic.

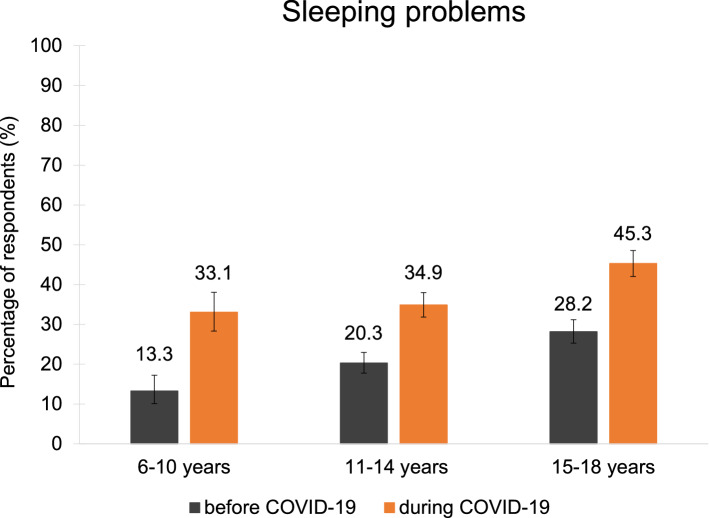

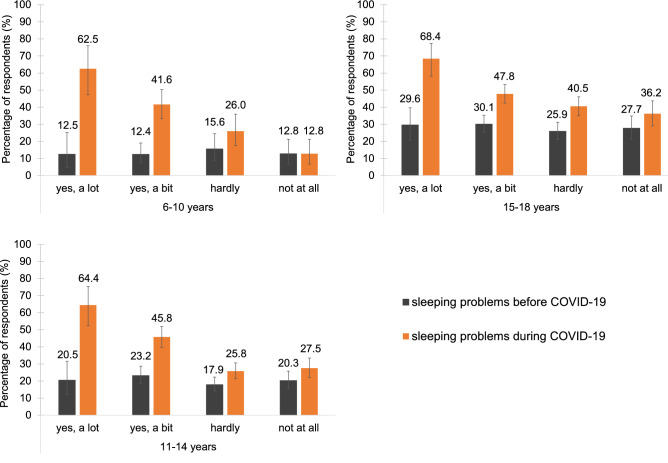

Compared to before COVID-19, all age groups reported a considerable and significant increase in sleeping problems during the pandemic (Fig. 4, Tables S4, S8): 6–10 years: from 13.3% to 33.1% (+ 19.8 percentage points); 11–14 years: 20.3% to 34.9% (+ 14.6 percentage points); 15–18 years: 28.2 to 45.3% (+ 17.1 percentage points).

Figure 4.

Change in sleeping problems. Children and adolescents reported almost twice as many (M = 1.9 times as much) sleeping problems during COVID-19 compared to before.

Similar to before the pandemic (Fig. 3, Table S4), the most common sleeping problems during COVID-19 were difficulties falling asleep and maintaining sleep. Furthermore, nightmares were the third most common issue in the 6–10-year-olds as well as in the 11–14-year-olds. In the 15–18-year-olds, difficulties falling asleep were still the most common problem. However, difficulties maintaining sleep, daytime sleepiness and difficulties getting up at the desired time became a lot more prominent during COVID-19. In all age groups, sleeping problems during COVID-19 mostly persisted between 1 and 6 months or more than 6 months. In terms of burden, 6–10-year-olds showed an increase from 42.0% to 54.8% in the moderate to severe category (Tables S4).

Furthermore, correlations (Table 2) and nonparametric statistics (Tables S7, S8) showed that a stronger COVID-19 related anxiety was significantly associated with a worse quality of sleep and a higher amount of sleeping problems. Across all age groups, 64% of the very anxious participants (“yes, a lot”) reported to have a reduced (“worse”; “a lot worse”) sleep quality during COVID-19. This percentage gradually decreased throughout the response categories. A very similar pattern emerged for sleeping problems, i.e., 65.1% of the very anxious participants reported having sleeping problems. Again, this percentage decreased throughout the remaining response categories (Fig. 5, Tables S7, S8).

Table 2.

Correlation coefficients (Kendall’s Tau, τb) for COVID-19 related anxiety and general sleep quality as well as sleeping problems during COVID-19.

| COVID-19 related anxiety | Age group | Overall | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6–10 years | 11–14 years | 15–18 years | 6–18 years | |||||||||||||||||

| n | τb | p | 95% CI | n | τb | p | 95% CI | n | τb | p | 95% CI | n | τb | p | 95% CI | |||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||||||||||

| General sleep quality | 345 | 0.34 | < 0.001 | 0.28 | 0.42 | 952 | 0.19 | < 0.001 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 930 | 0.14 | < 0.001 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 2257 | 0.20 | < 0.001 | 0.18 | 0.23 |

| Female | 187 | 0.35 | < 0.001 | 0.27 | 0.47 | 576 | 0.21 | < 0.001 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 676 | 0.16 | < 0.001 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 1439 | 0.20 | < 0.001 | 0.17 | 0.24 |

| Male | 188 | 0.33 | < 0.001 | 0.25 | 0.44 | 376 | 0.16 | < 0.001 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 254 | 0.09 | 0.086 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 818 | 0.16 | < 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.21 |

| Sleeping problems | 345 | 0.31 | < 0.001 | 0.25 | 0.39 | 953 | 0.19 | < 0.001 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 930 | 0.15 | < 0.001 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 2257 | 0.20 | < 0.001 | 0.18 | 0.23 |

| Female | 187 | 0.29 | < 0.001 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 576 | 0.18 | < 0.001 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 676 | 0.16 | < 0.001 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 1439 | 0.19 | < 0.001 | 0.16 | 0.23 |

| Male | 188 | 0.33 | < 0.001 | 0.24 | 0.44 | 376 | 0.18 | < 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 254 | 0.08 | 0.017 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 818 | 0.19 | < 0.001 | 0.15 | 0.24 |

τb 0.07–0.19 small effect; τb 0.20–0.33 medium effect; τb 0.34–0.49 strong effect; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval with lower and upper border.

Significant values are in bold.

Figure 5.

Sleeping problems and COVID-19 related anxiety. Reports of sleeping problems during COVID-19 were more frequent in children and adolescents being more anxious (“yes, a lot”) of COVID-19 than those being less anxious (“not at all”).

Comparisons of sleeping problems, especially in the 6–10- and 11–14-year-olds, further revealed that participants with the highest COVID-19 related anxiety also showed the strongest increases (i.e., largest effect sizes) in sleeping problems from before to during COVID-19 (Table S8). In the 15–18-year-olds, a general increase in sleeping problems, regardless of COVID-19 related anxiety was observed. However, similar to the other age groups, effect sizes were strongest for the most anxious participants.

Overall, sleeping problems and worsening of general sleep quality were significantly higher in female as compared to male participants (Table S8). However, effect sizes indicated rather small effects. Regarding COVID-19 related anxiety and sleeping problems, results show no significant differences between males and females in the “a lot” and “a bit” anxious category, thus indicating a similar level of sleeping problems in both sexes related to COVID-19 anxiety.

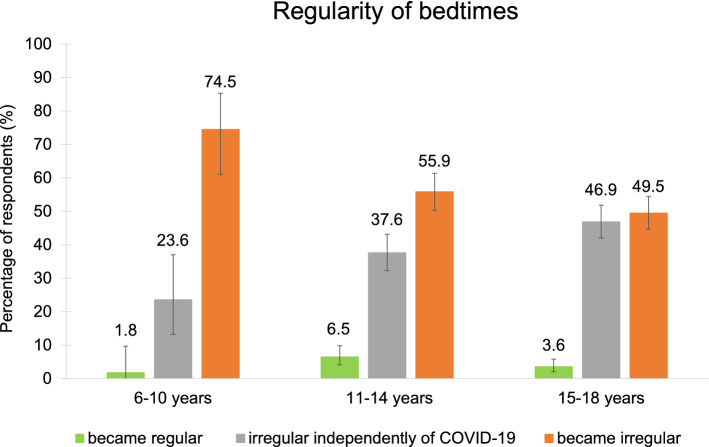

Regular bedtimes, time in bed and daytime sleepiness/napping

Comparing the regularity of their bedtime during COVID-19 to before, most participants stated that it was regular before and became irregular during the pandemic (Fig. 6, Table 3). Age groups differed significantly in the regularity of bedtimes, i.e., the 6–10-year-olds reported more regular bedtimes than the 11–14- and 15–18-year-olds (Table S9). Interestingly, around 50% of the 15–18-year-olds reported having irregular bedtimes independently of COVID-19 while the remaining half experienced irregular bedtimes only with the emergence of the pandemic.

Figure 6.

Changes in regularity of bedtimes. Especially for 6–10-year-olds, bedtimes became irregular during COVID-19.

Table 3.

Changes in time spent in bed, regularity of bedtimes and daytime sleep/napping.

| Response option | 6–10 years | 11–14 years | 15–18 years | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | N | % | 95% CI | n | N | % | 95% CI | n | N | % | 95% CI | ||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||||||||

| How did the time you usually spent in bed change? | |||||||||||||||

| (1) A lot shorter | 5 | 375 | 1.3 | 0.43 | 3.08 | 31 | 952 | 3.3 | 2.22 | 4.59 | 24 | 929 | 2.6 | 1.66 | 3.82 |

| (2) Considerably shorter | 7 | 375 | 1.9 | 0.75 | 3.81 | 47 | 952 | 4.9 | 3.65 | 6.51 | 55 | 929 | 5.9 | 4.49 | 7.64 |

| (3) Slightly shorter | 49 | 375 | 13.1 | 9.83 | 16.90 | 139 | 952 | 14.6 | 12.42 | 17.01 | 104 | 929 | 11.2 | 9.24 | 13.40 |

| (4) No change | 197 | 375 | 52.5 | 47.34 | 57.68 | 253 | 952 | 26.6 | 23.79 | 29.50 | 128 | 929 | 13.8 | 11.63 | 16.16 |

| (5) Slightly longer | 92 | 375 | 24.5 | 20.26 | 29.21 | 296 | 952 | 31.1 | 28.16 | 34.14 | 307 | 929 | 33.0 | 30.03 | 36.18 |

| (6) Considerably longer | 19 | 375 | 5.1 | 3.08 | 7.80 | 115 | 952 | 12.1 | 10.08 | 14.32 | 195 | 929 | 21.0 | 18.41 | 23.75 |

| (7) A lot longer | 6 | 375 | 1.6 | 0.59 | 3.45 | 71 | 952 | 7.5 | 5.87 | 9.31 | 116 | 929 | 12.5 | 10.43 | 14.79 |

| Do you go/ did you go to bed at the same time every day (+ /- 30 min)? My bedtime… | |||||||||||||||

| (1) Yes | 320 | 375 | 85.3 | 81.34 | 88.76 | 630 | 952 | 66.2 | 63.07 | 69.18 | 511 | 930 | 54.9 | 51.68 | 58.18 |

| (2) No | 55 | 375 | 14.7 | 11.24 | 18.66 | 322 | 952 | 33.8 | 30.82 | 36.93 | 419 | 930 | 45.1 | 41.82 | 48.32 |

| (1) Was regular before and got irregular during COVID-19 | 41 | 55 | 74.5 | 61.00 | 85.33 | 180 | 322 | 55.9 | 50.29 | 61.40 | 207 | 418 | 49.5 | 44.63 | 54.42 |

| (2) Was irregular before and got regular during COVID-19 | 1 | 55 | 1.8 | 0.05 | 9.72 | 21 | 322 | 6.5 | 4.08 | 9.80 | 15 | 418 | 3.6 | 2.02 | 5.85 |

| (3) Is irregular independently of COVID-19 | 13 | 55 | 23.6 | 13.23 | 37.02 | 121 | 322 | 37.6 | 32.27 | 43.12 | 196 | 418 | 46.9 | 42.02 | 51.80 |

| Do you usually sleep during the day? | |||||||||||||||

| (1) Yes | 6 | 375 | 1.6 | 0.59 | 3.45 | 88 | 952 | 9.2 | 7.48 | 11.26 | 258 | 930 | 27.7 | 24.89 | 30.74 |

| (2) No | 369 | 375 | 98.4 | 96.55 | 99.41 | 864 | 952 | 90.8 | 88.74 | 92.52 | 672 | 930 | 72.3 | 69.26 | 75.12 |

| (1) I nap from time to time | 5 | 6 | 83.3 | 35.88 | 99.58 | 56 | 88 | 63.6 | 52.69 | 73.63 | 154 | 258 | 59.7 | 53.43 | 65.73 |

| (2) I nap regularly | 0.00 | 0.00 | 7 | 88 | 8.0 | 3.26 | 15.71 | 46 | 258 | 17.8 | 13.36 | 23.06 | |||

| (3) I often fall asleep unintentionally during the day | 1 | 6 | 16.7 | 0.42 | 64.12 | 25 | 88 | 28.4 | 19.30 | 39.02 | 58 | 258 | 22.5 | 17.54 | 28.07 |

| Did the frequency of napping change during COVID-19? | |||||||||||||||

| (1) Yes | 22 | 375 | 5.9 | 3.71 | 8.75 | 154 | 952 | 16.2 | 13.89 | 18.67 | 346 | 930 | 37.2 | 34.09 | 40.40 |

| (2) No | 353 | 375 | 94.1 | 91.25 | 96.29 | 798 | 952 | 83.8 | 81.33 | 86.11 | 584 | 930 | 62.8 | 59.60 | 65.91 |

| (1) I nap a lot less than before | 3 | 22 | 13.6 | 2.91 | 34.91 | 6 | 154 | 3.9 | 1.44 | 8.29 | 19 | 346 | 5.5 | 3.34 | 8.44 |

| (2) I nap less than before | 3 | 22 | 13.6 | 2.91 | 34.91 | 10 | 154 | 6.5 | 3.16 | 11.62 | 34 | 346 | 9.8 | 6.90 | 13.46 |

| (3) I nap more than before | 12 | 22 | 54.5 | 32.21 | 75.61 | 98 | 154 | 63.6 | 55.51 | 71.23 | 202 | 346 | 58.4 | 52.99 | 63.63 |

| (4) I nap a lot more than before | 4 | 22 | 18.2 | 5.19 | 40.28 | 40 | 154 | 26.0 | 19.25 | 33.65 | 91 | 346 | 26.3 | 21.74 | 31.28 |

CI 95% confidence interval with lower and upper border, empty spaces response option was not chosen in this age group.

Concerning the time spent in bed (Q 9; i.e., not total sleep time), data indicated prolonged times spent in bed especially for the 11–14- as well as the 15–18-year-old during COVID-19 as compared to before (Table 3, Table S9).

The frequency of daytime naps in habitual nappers (M = 20%) changed during COVID-19, i.e., most participants reported to nap “more” to “a lot more” than before the pandemic. Asked about the circumstances of their napping, 28.4% of the 11–14 and 22.5% of the 15–18-year-olds-reported to often fall asleep unintentionally during the day (Table 3). Overall, females in the 11–14 and 15–18 years-old groups napped significantly more than their male counterparts (Table S10).

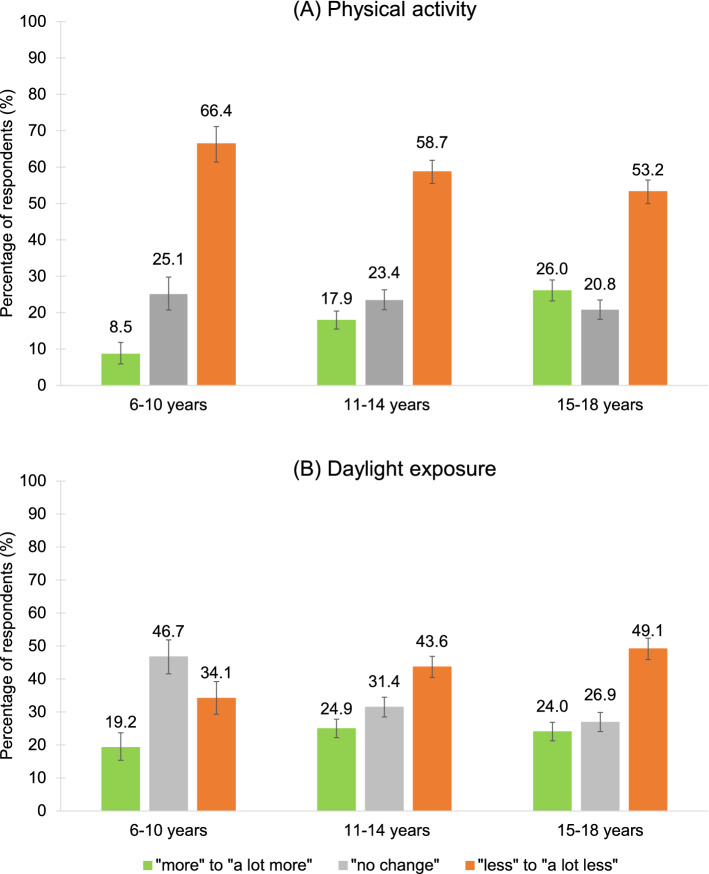

Physical activity, daylight exposure, usage of media devices

Across all age groups, the amount of physical activity changed in more than 75% of participants (Fig. 7A, Table S11), i.e., all age groups reported being “less” to “a lot less active” than before COVID-19 with the 6–10-year-olds being the least active (Table S12). However, an average of 23% also reported being “more” or “a lot more” active.

Figure 7.

Changes in (A) physical activity and (B) daylight exposure. (A) More than half of the participants were “less” or “a lot less” active during COVID-19 compared to before. With almost 70%, the youngest age group (6–10 years) showed the highest reduction of activity levels. (B) An average of 42% experienced “less” or “a lot less” daylight exposure during COVID-19.

Regarding daylight exposure, a gradual change across age groups could be observed, i.e., the older the participant the stronger the change in daylight exposure (Tables S11, S12). Most participants, especially 15–18-year-old males (Tables S11, S12), experienced “less” to “a lot less” daylight exposure during COVID-19 (M = 42%). However, an average of 22% of respondents also reported an increase (“more” to “a lot more”) in daylight exposure (Fig. 7B, Table S11).

Usage of media devices during COVID-19 increased considerably and with age. On average, 83% (6–10 years: 74%; 11–14 years: 85%; 15–18 years: 90%) spent more time in front of their smartphones, gaming consoles, PCs, or other media devices (Tables S11–S13).

Discussion

With this survey, we wanted to evaluate whether Austrian children and adolescents (6–18 years) showed changes in sleep patterns and behavior during COVID-19. Our results are in line with children and adolescent studies from other countries and show an overall delay of sleep and wake times in about 50% of the sample during the week as well as on weekends24,30–40. Furthermore, sleeping problems increased significantly during COVID-19. Compared to before, almost twice as many children and adolescents reported having sleeping problems during COVID-19. Moreover, COVID-19 related anxiety seemed to be an important factor for general sleep quality and sleeping problems. Our data show that the higher the COVID-19 related anxiety the worse the perception of general sleep quality and the more sleeping problems were reported. In addition, bedtimes became irregular in most of the participants, time in bed increased as well as the frequency of naps and daytime sleep. Lastly, children and adolescents were less active, spent less time in daylight and showed a considerable increase in the usage of media devices.

Our results regarding a delay in bed- and wake times are in line with previous surveys examining samples with similar age ranges24,31,32–40. Our data display a gradual increase towards later bed- and wake times with age, i.e., most 6–10-year-olds reported a delay of 0.5 to 1.5 h while the majority of the 15–18-year-olds show a considerable delay of 2 or more hours. The differences across age groups may be explained by the extent of parental monitoring, i.e., parents might be stricter with the youngest (e.g., enforcing set bedtimes) while adolescents are more independent in choosing their bed- and wake times41. Furthermore, humans experience a circadian phase delay around the onset of puberty42, i.e., due to developmental changes they shift to a later-typed chronotype that favors late nights and late mornings43. Thus, especially for adolescents, home confinement may have been an opportunity to shift their sleep schedules away from societal and towards their own circadian preferences14, thereby decreasing social jetlag during the pandemic44,45.

Similar to other studies, our data show a marked increase in the usage of media devices within all age groups during the pandemic35,38,46. These devices usually come with light emitting diode (LED)- displays that are highly enriched with a blue light component (446–483 nm)47. Since shorter wavelength light or blue light is the most effective in suppressing melatonin48, the usage of media devices before bedtime can lead to a phase delay by slowing down its secretion49, i.e., people feel/stay more alert and less sleepy for extended periods of time. Due to their increased sensitivity to light, this could be especially detrimental for the sleep regulation of pre- to mid- pubertal children (9.1–14.7 years)50,51. Additionally, social media use and screen time among children and adolescents have consistently been associated with poorer sleep patterns, i.e., later sleep onset, shorter sleep durations as well as increased sleeping problems like trouble falling asleep after nighttime awakening23,52.

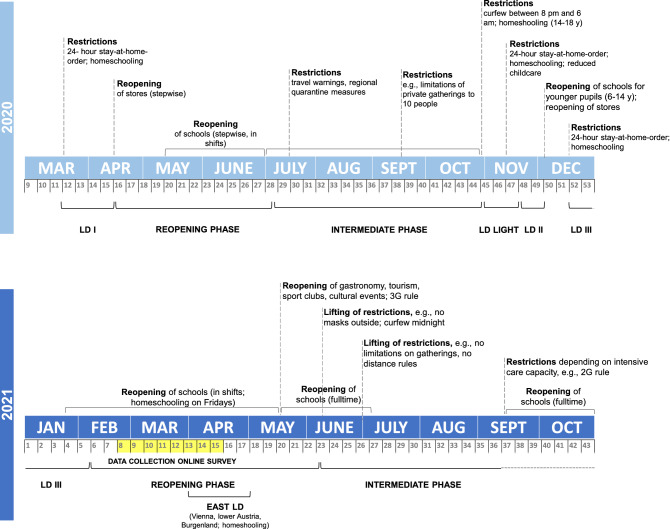

While both bed- and wake times showed a delay, the shift in wake times did not seem to be equal to the shift in bedtimes, i.e., participants reported an overall smaller delay in wake times during weekdays as well as at the weekend compared to the delay in bedtimes. Paradoxically, this might result in shortened sleep durations (i.e., shorter total sleep time) although the participants would have been more flexible to attune their sleep schedules to their individual needs during COVID-19. A shortening of sleep duration has also been reported in studies with 11–16- and 6–17-year-old Chinese children and adolescents as well as in an Italian sample37,53,54. However, several studies also observed an increase in sleep durations during the pandemic36,37–40. In addition, wake times of children and adolescents are more often determined by external factors55. Since in-person teaching still took place in Austria (at least during the time data from this survey was collected; Fig. 8) and the majority of participants went to school 1–5 times per week (homeschooling usually on Fridays or in the regions affected by the “East Lockdown”), this might be an explanation for the smaller delays in wake times during weekdays17. Furthermore, a mixture of hybrid, online and in-person teaching may have led to a greater night-to-night variability in sleep–wake patterns like it has recently been shown in a sample of U.S. students (13–18 years)56. However, since we did not assess the actual bedtimes, wake times and sleep durations before and during the pandemic, the assumption that the pandemic situation might have intensified this effect cannot be further verified.

Figure 8.

Timeline of COVID-19 related measures in Austria from March 2020 to September 2021 including information about lockdowns (LD) and school closures/reopenings. Highlighted in yellow is the time window of data collection for the online survey.

Around one third of the participants reported a drop in general sleep quality and almost twice as many respondents reported having sleeping problems (38.0% vs. 20.9%). Similar to other studies, females rated their sleep quality significantly worse than males and also reported more sleeping problems36,57. However, effect sizes for these differences were rather small. Further, insomnia symptoms (difficulties falling asleep and maintaining sleep), nightmares and daytime sleepiness were the most prevalent problems (similar ranking as before the pandemic)24,37,38,40,58,59. Compatible with that are the reports regarding an increase in naps and the time spent in bed, thus possibly further facilitating an overall disruption of daily structure resulting in irregular bedtimes.

There might be multiple reasons for the increase in sleeping problems during COVID-19: First, our data show a considerable decrease of physical activity in around three quarters of the participants with the youngest (6–10 years old) showing the strongest reduction (88.6% answered to be “less” to “a lot less” active). This is especially concerning since the Austrian recommendation for physical activity for children and adolescents between 6 and 18 years is 60 min or more per day with moderate to vigorous intensity60. Sedentary behavior and obesity do not only have detrimental short- and long-term effects on physical (e.g., cardiovascular disease, high fasting insulin levels/ type-2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, cancer, musculoskeletal disorders)60–63 and mental health (e.g., depression, stress, anxiety, low self-esteem)64,65 but also on the quality of sleep. For example, it has been associated with an increased risk for insomnia, shorter sleep durations, disturbed or interrupted sleep as well as increased daytime sleepiness65–69. Our data provide indications towards these negative effects and support findings from other studies conducted during the pandemic35,46. In addition, regular physical exercise and sleep strengthen the immune system and can thus be an important tool against COVID-19 and other infections69–73.

A second reason for the increase in sleeping problems might be the decrease in daylight exposure. Across all age groups, 42.2% experienced “less” to “a lot less” daylight exposure during the pandemic. Daylight is a natural “Zeitgeber” and helps to synchronize the circadian system with the sleep–wake cycle74,75. It has been shown that low light exposure during the day sensitizes the circadian system for light exposure during the evening hours, i.e. (artificial) light exposure around and after dusk leads to greater melatonin suppression and a delay of sleep onset75–78. Thus, especially the increase in difficulties falling asleep and getting up at the desired time the next morning may have been partly influenced by insufficient daylight exposure.

Further, our data show a positive correlation between sleeping problems and COVID-19 related anxiety with the strongest effects being detected in the youngest participants (6–10 years). This is concerning since the co-occurrence of sleeping problems and anxiety/depression during childhood and adolescence is indicative of long-term psychological difficulties in adulthood78–81. For example, a longitudinal study examining sleeping problems in childhood (mean age 10.3 years) and 18 years later showed that subjects with sleeping problems during childhood were 4.51 times more likely to have persistent internal symptoms (depression, anxiety, somatic complaints) in adulthood82. Apart from long-term effects, anxiety can also have immediate effects on sleep, e.g., making it more difficult to fall asleep and/or stay asleep due to nighttime fears and nightmares. Persistent rumination, worrying and negative thoughts can lead to heightened levels of physiological arousal, thus potentially delaying/ disturbing sleep and leading to a perpetual cycle of lack of sleep, daytime fatigue, impaired academic and social functioning as well as an impaired ability to regulate mood and emotional responses83. Our results also fit well with reports from adult studies showing that reduced sleep quality during COVID-19 was most prevalent in people with elevated symptoms of anxiety and depression44,83–87 as well as with low social support88. Interestingly, females and males did not show significant differences for COVID-19 related anxiety and sleeping problems thus indicating that both sexes were equally affected.

Lastly, our data should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, we used a self-designed, thus not validated, questionnaire and our data was not derived from a randomized sample. Hence, there might be potential biases regarding sample composition, e.g., motivation to finish both parts of the survey which may not allow for direct comparisons to a norm or other studies. Nevertheless, we think our approach was highly justified given the unprecedented COVID-19 situation which necessitated specific questions related to the COVID-19 burdens children and adolescent may have suffered from. Third, the online survey could only reach participants being able to use electronic devices. However, due to COVID-19 restrictions (e.g., lockdown, social distancing), online recruitment represented a unique way of accessing a large number of participants within a limited time window. Furthermore, we used retrospective questions to compare the situation during COVID-19 with the time before lockdowns. Although this method seems to be sufficiently reliable89, we cannot rule out the occurrence of recall bias, especially in our youngest participants (6 years). Additionally, they may not have been able to understand all of the questions correctly. Thus, although 6-year-olds should be able to answer questions about their sleep25–29, these data need to be interpreted with caution. However, excluding the 6-year-olds from the analyses would not have affected the overall results in the respective age group. Data further seemed to be valid since they were in line with the patterns observed in the other age groups (11–14 years, 15–18 years). Finally, we want to highlight that the sample size, including a larger number of very young children, is a strength of the study, together with the interesting findings that (i) not only sleeping problems alarmingly increased across age groups, but also that (ii) daily life habits changed to maladaptive responses such as moving less and spending less time in natural daylight, as well as an increased media device usage.

In conclusion, our data show considerable changes in sleep patterns and behavior during COVID-19 as compared to before the pandemic. Overall, a reduced sleep quality marked by an increase in sleeping problems, irregular bedtimes as well as increased daytime sleepiness and daytime sleep was observed. Furthermore, a stronger COVID-19 related anxiety was correlated with more sleeping problems especially in the youngest (6–10 years). Since sleep disturbances can be an indicator for psychological impairments/ distress, caregivers and clinicians should pay special attention to the behavior of children and adolescents during the pandemic and beyond. Furthermore, sleeping problems during childhood and adolescence can have long-lasting negative effects90. Thus, health ministries around the world would be wise to increase their efforts in the implementation of prevention and intervention programs and expand the visibility and accessibility of existing health services for children and adolescents.

Methods

Survey design and participants

The online survey91 was conducted for a limited time window from February 21, 2021 to April 19, 2021 and targeted 6- to 18-year-old children and adolescents (cross-sectional design). In order to collect nationwide data, the survey was promoted via the Austrian Press Agency (APA), national television (ORF, Austrian Broadcasting Corporation), children and youth organizations, as well as via word of mouth (e.g., WhatsApp groups, Facebook, emails). The recipients of the survey questionnaire link were encouraged to disseminate the invitation to other people.

The survey was divided into two parts: (1) questions about feelings, fears, worries, and thoughts regarding COVID-19 (reported here17,30), (2) questions about changes in sleep habits, activity levels and usage of media devices (e.g., smartphone, PC, TV, game console) during COVID-19 and, retrospectively, before the pandemic. After finishing part 1, participants could decide whether they wanted to continue to part 2 or end the survey. Data were organized per age groups: 6–10 years, 11–14 years, and 15–18 years.

Participants entering their email address or phone number at the end of the survey (double chance to win for completing both questionnaire parts) had the chance to win one of 35 vouchers (20€, 30€ or 50€) for tickets from an online ticket platform or a cinema. In agreement with the Ethics Committee of the Austrian Society of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine (ÖGKJ) and the legal department of the University of Salzburg, separate informed parental consent was skipped due to the anonymous nature of the survey. Thus, implied consent was obtained when participants completed the (voluntary and anonymous) questionnaire. Furthermore, participants were provided with a link where they could find more detailed information regarding the aim of the survey, privacy policy as well as data processing and results. The survey was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Salzburg (EK-GZ 122013) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Since the time course and extent of COVID-19 related measures is specific to each country, Fig. 8 displays information about the main measures implemented in Austria. During the study period, most parts of Austria were in a reopening phase after about 3.5 months of strict lockdown—except for Vienna, lower Austria and Burgenland which went back into strict lockdown (i.e., “East Lockdown”) between end of March and the end of the study period on April 19th, 2021. During reopening phase, schools operated in a shift system, i.e., classes were divided into two groups: group 1 went to school on Mondays and Tuesdays, group 2 on Wednesdays and Thursdays. On Fridays all students were taught via homeschooling. Leisure activities, e.g., sports clubs, museums, zoos, libraries, private meetings with other families, were possible to a limited degree. Students affected by the “East Lockdown” were taught entirely via homeschooling and were not allowed to leave their homes for non-essential activities.

Outcome measures

An 18-item investigator-created questionnaire was used to assess changes in sleep habits and behavior of children and adolescents during, and retrospectively, before the COVID-19 pandemic (for the full questionnaire, please refer to Supplementary Information). Participants were asked to indicate how they perceived their sleep and associated behavior as having changed for the better or the worse. In most cases, this was measured as a binary “yes” or “no” item, followed by a rating of the degree to which sleep/behavior had changed (e.g., (1) a lot worse, (2) worse, (3) better, (4) a lot better). However, for some items, the question asked for an immediate rating without a previous “yes”/”no” decision (e.g., (1) a lot worse, (2) worse, (3) no change, (4) better, (5) a lot better).

Demographic data

For demographic purposes, gender, age, region of Austria, and school type were assessed (see Supplementary Information Q 1–4).

Bed- and wake times

The survey first asked whether participants’ typical bed- and wake times on both weekdays and weekends changed during COVID-19 compared to before. If the answer was “yes” they were asked to indicate in which direction their bed- and wake times changed (e.g., 1 h later) (Q 5–8).

General sleep quality, sleeping problems and COVID-19 related anxiety

Furthermore, questions regarding general sleep quality (i.e., change during COVID-19 compared to before; Q 11) and the occurrence of sleeping problems (type, duration and degree of burden) before and during COVID-19 were asked (Q12-17).

To see whether general sleep quality and sleeping problems were reported more frequently in COVID-19 anxious participants, a question from the first part of the survey regarding COVID-19 related anxiety was used (Q 23).

Regular bedtimes, time in bed and daytime sleepiness/napping

The survey also asked participants (1) whether there was a change in the regularity of bedtimes during COVID-19 compared to before (Q 10), (2) how their time spent in bed changed during COVID-19 compared to before (Q 9), (3) whether they generally sleep during the day and if so, how often they usually nap (Q 18). Furthermore, nappers were asked whether there were any changes in the frequency of napping during COVID-19 compared to before (Q 19).

Physical activity, daylight exposure, usage of media devices

The last part of the survey was devoted to factors that are known to have an impact on sleep and sleeping problems, i.e., (1) physical activity (Q 20), (2) daylight exposure (Q 21), and (3) usage of media devices (Q 22).

Data analysis

Data was analyzed with jamovi version 1.6.23.092. Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, 95% confidence intervals) were applied to characterize sociodemographic variables, bed- and wake times, general sleep quality, sleeping problems, COVID-19 related anxiety, regular sleep times, time in bed, and daytime sleepiness/napping as well as physical activity, daylight exposure and usage of media devices. Furthermore, nonparametric analyses (Kruskal–Wallis with post-hoc Dwass–Steel–Critchlow–Fligner (DSCF)93 test, Mann–Whitney-U test) were conducted to determine differences between age groups as well as between males and females. For changes in the occurrence of sleeping problems before and during COVID-19, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were calculated. Moreover, effect sizes (rank biserial correlation r, ε2) were calculated to indicate the strength of the observed effects94. Kendall’s Tau correlation coefficients (τb) were calculated to test for a relation between COVID-19 related anxiety and (1) general sleep quality and (2) sleeping problems94–98. Correlations were designated as small (0.07–0.19), medium (0.20–0.33), and large (> 0.34)98–102. For all calculations, p-values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

K.B. (P32028) and E-S. E. (Y777) were funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF).

Author contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analyses, and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Data availability

Supplementary Information is provided with the paper to support the current results. Additional data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kathrin Bothe, Email: kathrin.bothe@plus.ac.at.

Kerstin Hoedlmoser, Email: kerstin.hoedlmoser@plus.ac.at.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-24509-7.

References

- 1.Brown WJ, et al. A review of sleep disturbance in children and adolescents with anxiety. J. Sleep Res. 2018;27:e12635. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ordway MR, et al. A systematic review of the association between sleep health and stress biomarkers in children. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021;59:101494. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore M. Behavioral sleep problems in children and adolescents. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings. 2012;19:77–83. doi: 10.1007/s10880-011-9282-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ernst M, et al. Pubertal maturation and sex effects on the default-mode network connectivity implicated in mood dysregulation. Transl. Psychiatry. 2019;9:103. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0433-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.İçer S. Functional connectivity differences in brain networks from childhood to youth. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 2020;30:75–91. doi: 10.1002/ima.22366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baum KT, et al. Sleep restriction worsens mood and emotion regulation in adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2014;55:180–190. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregory AM, O'Connor TG. Sleep problems in childhood: A longitudinal study of developmental change and association with behavioral problems. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2002;41:964–971. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200208000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hysing M, Sivertsen B, Garthus-Niegel S, Eberhard-Gran M. Pediatric sleep problems and social-emotional problems. A population-based study. Infant Behav. Dev. 2016;42:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gregory AM, Sadeh A. Sleep, emotional and behavioral difficulties in children and adolescents. Sleep Med. Rev. 2012;16:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts RE, Ramsay Roberts C, Ger Chen I. Impact of insomnia on future functioning of adolescents. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002;53:561–569. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McMakin DL, et al. The impact of experimental sleep restriction on affective functioning in social and nonsocial contexts among adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2016;57:1027–1037. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bothe K, Hahn MA, Wilhelm I, Hoedlmoser K. The relation between sigma power and internalizing problems across development. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021;135:302–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker SP, Gregory AM. Editorial Perspective: Perils and promise for child and adolescent sleep and associated psychopathology during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2020;61:757–759. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altena E, et al. Dealing with sleep problems during home confinement due to the COVID-19 outbreak: Practical recommendations from a task force of the European CBT-I Academy. J. Sleep Res. 2020;29:e13052. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chawla N, Tom A, Sen MS, Sagar R. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on children and adolescents: A systematic review. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2021;43:294–299. doi: 10.1177/02537176211021789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panchal U, et al. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: Systematic review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01856-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schabus M, Eigl E-S. Jetzt Sprichst Du! Pädiatr. Pädol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00608-021-00909-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarrin DC, Chen IY, Ivers H, Morin CM. The role of vulnerability in stress-related insomnia, social support and coping styles on incidence and persistence of insomnia. J. Sleep Res. 2014;23:681–688. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alvaro PK, Roberts RM, Harris JK. A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. Sleep. 2013;36:1059–1068. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baradaran Mahdavi S, et al. Association of sunlight exposure with sleep hours in iranian children and adolescents: The CASPIAN-V study. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2020;66:4–14. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmz023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarnig G, Jaunig J, van Poppel MNM. Association of COVID-19 mitigation measures with changes in cardiorespiratory fitness and body mass index among children aged 7 to 10 years in Austria. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4:e2121675–e2121675. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.21675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greier K, et al. Physical activity and sitting time prior to and during COVID-19 lockdown in Austrian high-school students. AIMS Public Health. 2021;8:531–540. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2021043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hale L, Guan S. Screen time and sleep among school-aged children and adolescents: A systematic literature review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2015;21:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma M, Aggarwal S, Madaan P, Saini L, Bhutani M. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on sleep in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2021;84:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holzhausen EA, et al. A comparison of self- and proxy-reported subjective sleep durations with objective actigraphy measurements in a survey of Wisconsin children 6–17 years of age. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2021;190:755–765. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwaa254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meltzer LJ, et al. The Children's Report of Sleep Patterns-Sleepiness Scale: A self-report measure for school-aged children. Sleep Med. 2012;13:385–389. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaina A, Sekine M, Chen X, Hamanishi S, Kagamimori S. Validity of child sleep diary questionnaire among junior high school children. J. Epidemiol. 2004;14:1–4. doi: 10.2188/jea.14.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conijn JM, Smits N, Hartman EE. Determining at what age children provide sound self-reports: An illustration of the validity-index approach. Assessment. 2019;27:1604–1618. doi: 10.1177/1073191119832655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riley AW. Evidence that school-age children can self-report on their health. Ambul. Pediatr. 2004;4:371–376. doi: 10.1367/A03-178R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eigl E-S, Widauer SS, Schabus M. Burdens and psychosocial consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic for Austrian children and adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2022;13:97124. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.971241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cellini N, Di Giorgio E, Mioni G, Di Riso D. Sleep and psychological difficulties in Italian school-age children during COVID-19 lockdown. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2021;46:153–167. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsab003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cachón-Zagalaz J, Zagalaz-Sánchez ML, Arufe-Giráldez V, Sanmiguel-Rodríguez A, González-Valero G. Physical activity and daily routine among children Aged 0–12 during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:703. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lim MTC, et al. School closure during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: Impact on children's sleep. Sleep Med. 2021;78:108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Becker SP, et al. Prospective Examination of Adolescent Sleep Patterns and Behaviors Before and During COVID-19. Sleep. 2021;44:zsab054. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsab054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burkart S, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on elementary schoolers' physical activity, sleep, screen time and diet: A quasi-experimental interrupted time series study. Pediatr. Obes. 2022;17:e12846. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Illingworth G, Mansfield KL, Espie CA, Fazel M, Waite F. Sleep in the time of COVID-19: Findings from 17000 school-aged children and adolescents in the UK during the first national lockdown. SLEEP Adv. 2022;3:zpab021. doi: 10.1093/sleepadvances/zpab021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao J, Xu J, He Y, Xiang M. Children and adolescents’ sleep patterns and their associations with mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Shanghai, China. J. Affect. Disord. 2022;301:337–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bruni O, et al. Changes in sleep patterns and disturbances in children and adolescents in Italy during the Covid-19 outbreak. Sleep Med. 2022;91:166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaditis AG, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on sleep duration in children and adolescents: A survey across different continents. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2021;56:2265–2273. doi: 10.1002/ppul.25367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramos Socarras L, Potvin J, Forest G. COVID-19 and sleep patterns in adolescents and young adults. Sleep Med. 2021;83:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Randler C, Bilger S, Díaz-Morales JF. Associations among sleep, chronotype, parental monitoring, and pubertal development among German adolescents. J. Psychol. 2009;143:509–520. doi: 10.3200/JRL.143.5.509-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hagenauer MH, Perryman JI, Lee TM, Carskadon MA. Adolescent changes in the homeostatic and circadian regulation of sleep. Dev. Neurosci. 2009;31:276–284. doi: 10.1159/000216538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carskadon MA, Tarokh L. Developmental changes in sleep biology and potential effects on adolescent behavior and caffeine use. Nutr. Rev. 2014;72(Suppl 1):60–64. doi: 10.1111/nure.12147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Florea C, et al. Sleep during COVID-19 lockdown: A cross-cultural study investigating job system relevance. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021;191:114463. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2021.114463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blume C, Schmidt MH, Cajochen C. Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on human sleep and rest-activity rhythms. Curr. Biol. 2020;30:R795–R797. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Viner R, et al. School closures during social lockdown and mental health, health behaviors, and well-being among children and adolescents during the First COVID-19 wave: A systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176:400–409. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.5840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Touitou Y, Touitou D, Reinberg A. Disruption of adolescents’ circadian clock: The vicious circle of media use, exposure to light at night, sleep loss and risk behaviors. J. Physiol.-Paris. 2016;110:467–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Komada Y, Aoki K, Gohshi S, Ichioka H, Shibata S. Effects of television luminance and wavelength at habitual bedtime on melatonin and cortisol secretion in humans. Sleep Biol. Rhythms. 2015;13:316–322. doi: 10.1111/sbr.12121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chang A-M, Aeschbach D, Duffy JF, Czeisler CA. Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:1232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418490112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crowley SJ, Cain SW, Burns AC, Acebo C, Carskadon MA. Increased sensitivity of the circadian system to light in early/mid-puberty. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015;100:4067–4073. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Drescher AA, Goodwin JL, Silva GE, Quan SF. Caffeine and screen time in adolescence: Associations with short sleep and obesity. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2011;7:337–342. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scott H, Biello SM, Woods HC. Social media use and adolescent sleep patterns: Cross-sectional findings from the UK millennium cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e031161. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liao S, et al. Bilateral associations between sleep duration and depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sleep Med. 2021;84:289–293. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dellagiulia A, et al. Early impact of COVID-19 lockdown on children’s sleep: A 4-week longitudinal study. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2020;16:1639–1640. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Foundation, N. S. Sleep in America Poll: Teens and Sleep. (National Sleep Foundation, 2006).

- 56.Meltzer LJ, et al. COVID-19 instructional approaches (in-person, online, hybrid), school start times, and sleep in over 5,000 U.S. adolescents. Sleep. 2021 doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsab180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barbieri V, et al. Mental Health in, children adolescents after the first year of the covid-19 pandemic: A large population-based survey in south Tyrol, Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:5220. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19095220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wearick-Silva LE, Richter SA, Viola TW, Nunes ML. Sleep quality among parents and their children during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pediatr. (Rio J.) 2022;98:248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2021.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ustuner Top F, Cam HH. Sleep disturbances in school-aged children 6–12 years during the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2022;63:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2021.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bauer, R. et al. Vol. 17(1) of scientific reports (Austrian Health Promotion Fund, 2020).

- 61.Carson V, et al. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth: An update. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016;41:S240–S265. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2015-0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scandiffio JA, Janssen I. Do adolescent sedentary behavior levels predict type 2 diabetes risk in adulthood? BMC Public Health. 2021;21:969. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10948-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Panday SL. The growing problem of pediatric obesity. Nurs. Made Incred. Easy. 2017;15:24–30. doi: 10.1097/01.NME.0000525550.29409.0a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Costigan SA, Barnett L, Plotnikoff RC, Lubans DR. The health indicators associated with screen-based sedentary behavior among adolescent girls: A systematic review. J. Adolesc. Health. 2013;52:382–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Suchert V, Hanewinkel R, Isensee B. Sedentary behavior and indicators of mental health in school-aged children and adolescents: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2015;76:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brand S, et al. High exercise levels are related to favorable sleep patterns and psychological functioning in adolescents: A comparison of athletes and controls. J. Adolesc. Health. 2010;46:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang Y, Shin JC, Li D, An R. Sedentary behavior and sleep problems: A Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2017;24:481–492. doi: 10.1007/s12529-016-9609-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim Y, Umeda M, Lochbaum M, Sloan RA. Examining the day-to-day bidirectional associations between physical activity, sedentary behavior, screen time, and sleep health during school days in adolescents. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0238721–e0238721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brunetti VC, O'Loughlin EK, O'Loughlin J, Constantin E, Pigeon É. Screen and nonscreen sedentary behavior and sleep in adolescents. Sleep Health. 2016;2:335–340. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.da Silveira MP, et al. Physical exercise as a tool to help the immune system against COVID-19: An integrative review of the current literature. Clin. Exp. Med. 2021;21:15–28. doi: 10.1007/s10238-020-00650-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pedersen BK, Hoffman-Goetz L. Exercise and the immune system: Regulation, integration, and adaptation. Physiol. Rev. 2000;80:1055–1081. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.3.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Besedovsky L, Lange T, Born J. Sleep and immune function. Pflugers Arch. 2012;463:121–137. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-1044-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dimitrov S, et al. Gαs-coupled receptor signaling and sleep regulate integrin activation of human antigen-specific T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2019;216:517–526. doi: 10.1084/jem.20181169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Knoop M, et al. Daylight: What makes the difference? Light. Res. Technol. 2019;52:423–442. doi: 10.1177/1477153519869758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Boubekri M, et al. The impact of optimized daylight and views on the sleep duration and cognitive performance of office workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:3219. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hébert M, Martin SK, Lee C, Eastman CI. The effects of prior light history on the suppression of melatonin by light in humans. J. Pineal Res. 2002;33:198–203. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079X.2002.01885.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smith KA, Schoen MW, Czeisler CA. Adaptation of human pineal melatonin suppression by recent photic history. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;89:3610–3614. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chang A-M, Scheer FAJL, Czeisler CA. The human circadian system adapts to prior photic history. J. Physiol. 2011;589:1095–1102. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.201194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chorney DB, Detweiler MF, Morris TL, Kuhn BR. The interplay of sleep disturbance, anxiety, and depression in children. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2008;33:339–348. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gregory AM, et al. Prospective longitudinal associations between persistent sleep problems in childhood and anxiety and depression disorders in adulthood. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2005;33:157–163. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-1824-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bai S, et al. Longitudinal study of sleep and internalizing problems in youth treated for pediatric anxiety disorders. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2020;48:67–77. doi: 10.1007/s10802-019-00582-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Touchette E, et al. Prior sleep problems predict internalising problems later in life. J. Affect. Disord. 2012;143:166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dahl, R. E. & Lewin, D. S. Sleep Disturbance in Children and Adolescents with Disorders of Development: Its Significance and Management. Clinics in Developmental Medicine, No. 155. 161–168 (Cambridge University Press, 2001).

- 84.Ulrich AK, et al. Stress, anxiety, and sleep among college and university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Health. 2021 doi: 10.1080/07448481.2021.1928143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang X, et al. Anxiety and sleep problems of college students during the outbreak of COVID-19. Front. Psych. 2020;11:588693–588693. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.588693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cellini N, Canale N, Mioni G, Costa S. Changes in sleep pattern, sense of time and digital media use during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. J. Sleep Res. 2020;29:e13074. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Casagrande M, Favieri F, Tambelli R, Forte G. The enemy who sealed the world: Effects quarantine due to the COVID-19 on sleep quality, anxiety, and psychological distress in the Italian population. Sleep Med. 2020;75:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Grey I, et al. The role of perceived social support on depression and sleep during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113452. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hipp L, Bünning M, Munnes S, Sauermann A. Problems and pitfalls of retrospective survey questions in COVID-19 studies. Surv. Res. Methods. 2020 doi: 10.18148/srm/2020.v14i2.7741. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Casement MD, Keenan KE, Hipwell AE, Guyer AE, Forbes EE. Neural reward processing mediates the relationship between insomnia symptoms and depression in adolescence. Sleep. 2016;39:439–447. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.LimeSurvey: An Open Source Survey Tool (LimeSurvey Project, 2012).

- 92.The jamovi project v. jamovi (1.6.23.0). (The jamovi project, 2021).

- 93.Critchlow E, Fligner MA. On distribution-free multiple comparisons in the one-way analysis of variance. Commun. Stat. 1991;20:127–139. doi: 10.1080/03610929108830487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kerby DS. The simple difference formula: An approach to teaching nonparametric correlation. Compr. Psychol. 2014 doi: 10.2466/11.IT.3.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Boone HN, Boone DA. Analyzing likert data. J. Ext. 2012;50:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Clason DL, Dormody TJ. Analyzing data measured by individual likert-type items. J. Agric. Educ. 1994;35:31–35. doi: 10.5032/jae.1994.04031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Croux C, Dehon C. Influence functions of the Spearman and Kendall correlation measures. Stat. Methods Appl. 2010;19:497–515. doi: 10.1007/s10260-010-0142-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Howell DC. Statistical Methods for Psychology. 4. Duxbury Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gilpin AR. Table for conversion of Kendall'S Tau to Spearman'S Rho within the context of measures of magnitude of effect for meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1993;53:87–92. doi: 10.1177/0013164493053001007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cohen, J. The effect size. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences 77–83 (1988).

- 102.Rosenthal JA. Qualitative descriptors of strength of association and effect size. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 1996;21:37–59. doi: 10.1300/J079v21n04_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Supplementary Information is provided with the paper to support the current results. Additional data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.