Abstract

In order to evaluate the pathological role of verotoxin 2 (VT2), we investigated the effects of VT2 on neutrophil apoptosis in vitro. The results showed that VT2 caused a significant delay in spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis and that the effect was abrogated by a protein kinase C inhibitor. These data indicate that longer survival of neutrophils may aggravate neutrophil-mediated tissue damage in VT2-associated diseases.

Verotoxin (VT)-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC) strains of serotype O157:H7 have been implicated as causes of a wide spectrum of diseases, ranging from bloody diarrhea and hemorrhagic colitis to hemolytic uremic syndrome. A number of studies have shown that production of VTs from VTEC O157:H7 has an essential role in these diseases (1, 3, 5, 10). Two serologically distinct VTs from this microorganism, VT1 and VT2, have been identified. Biological and physical analysis has demonstrated that VT1 and VT2 share biological activities and receptor specificities (7, 19). Infiltration of neutrophils at the inflamed site of VTEC-associated diseases has been well documented, and recent studies suggest an essential role of neutrophils in the pathogenesis of these diseases (4, 5, 13). Neutrophils have the shortest life span among circulating leukocytes. Senescent neutrophils rapidly die, exhibiting the characteristic morphological changes indicative of programmed cell death, or apoptosis. Neutrophils undergoing apoptosis lose their functions and are sequestered from the inflammatory site through phagocytosis by macrophages (2, 17). Therefore, apoptosis may be an important mechanism for regulating the balance between host defense and neutrophil-mediated tissue injury. However, the regulatory effects of VTs on neutrophil apoptosis remain unknown. Thus, we conducted the present study to investigate the effect of VT2 on neutrophil apoptosis.

Inhibition of spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis by VT2.

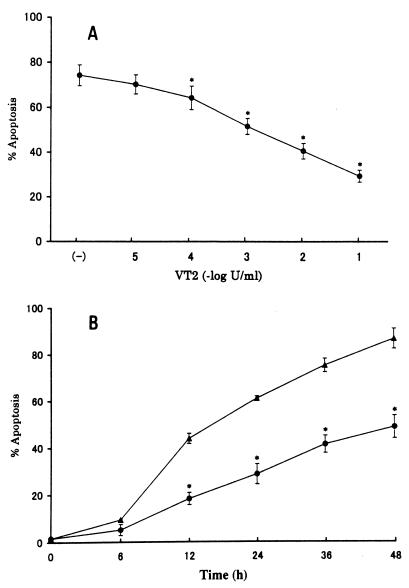

VT2 was purified from VTEC O157:H7 strain KSE-1571 by cation-exchange chromatography and high-performance liquid chromatography (11). Contamination by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the preparation of VT2 was determined to be less than 0.03 EU/ml by Limulus amebocyte lysate assay. Heparinized peripheral blood was obtained from healthy volunteers, and neutrophils were isolated by 3% dextran sedimentation followed by density gradient centrifugation with Ficoll-Paque. In order to determine whether or not VT2 affects spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis, neutrophils (2 × 106 cells) were incubated with culture medium (RPMI 1640, 10% fetal calf serum) containing purified VT2 for 24 h. Subsequently, cells were treated with hypotonic fluorochrome solution (100 μg of propidium iodide per ml in 0.1% sodium citrate and 0.1% Triton X-100) and stored overnight at 4°C. The fluorescence intensity of each individual nucleus was determined by a FACScan flow cytometer (14). As shown in Fig. 1A, 74% of the cells underwent apoptosis spontaneously following 24 h of incubation, which is consistent with previous reports (15, 20). The apoptotic responses of neutrophils were apparently inhibited by VT2 in a dose-dependent manner. Figure 1B illustrates the time kinetics of the effect of purified VT2 on spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis. Cells were incubated with 0.1 U of VT2 per ml at 37°C for up to 48 h. Purified VT2 significantly prevented spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis in a time-dependent manner. Morphological evaluation of cultured neutrophils also revealed an apparent inhibition of spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis by VT2 (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Effect of VT2 on neutrophil apoptosis. (A) Neutrophils (2 × 106 cells) were incubated in triplicate with varying concentrations of VT2 (●) for 24 h. (B) Neutrophils were incubated with medium alone (▴) or with 0.1 U of VT2 per ml (●) for the periods indicated. Cells were subsequently harvested, and cellular apoptosis was determined by flow cytometric analysis. Data are shown as percentages of apoptotic cells; they represent the means and indicated standard deviations of a representative experiment. These results were confirmed in six separate experiments performed with neutrophils isolated from independent donors. Asterisks represent P values of <0.01 compared with controls.

DNA fragmentation.

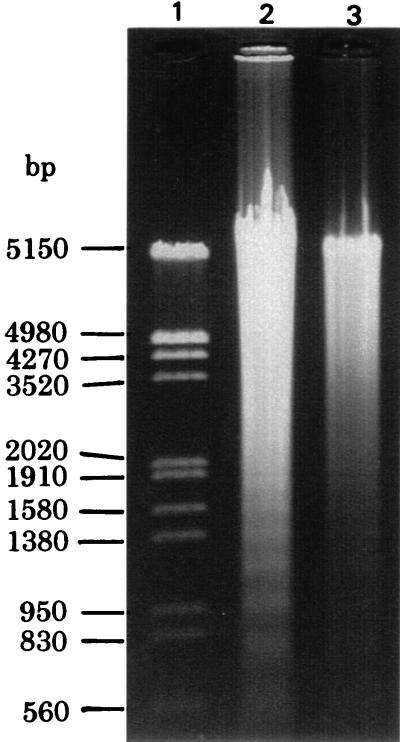

The VT2-induced delay in neutrophil apoptosis was verified by confirming DNA fragmentation. Neutrophils (7 × 106 cells) were incubated with 400 μl of cold hypotonic lysing buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA, and 0.2% Triton X-100) for 20 min on ice, and the lysate was centrifuged. Low-molecular-weight DNA in the supernatant was obtained by phenol extraction. After digesting with RNase, the samples were electrophoresed in a 1% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. As shown in Fig. 2, neutrophils incubated with medium alone for 24 h demonstrated an increased amount of low-molecular-weight DNA, which was electrophoresed in a dense ladder pattern. Neutrophils incubated with 0.1 U of VT2 per ml exhibited low-molecular-weight DNA in lesser quantities without exhibiting a ladder formation.

FIG. 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of low-molecular-weight DNA. Neutrophils were incubated with medium alone (lane 2) or with 0.1 U of VT2 per ml (lane 3) for 24 h. After treatment, low-molecular-weight DNA of the neutrophils was detected by agarose gel electrophoresis. The results are representative of three separate experiments using neutrophils isolated from three different donors.

Elimination of VT2 by anti-VT2 antibody and heat inactivation.

Purified VT2 at a concentration of 0.02 U/ml was treated with latex beads conjugated with anti-VT2 antibody (Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan). This treatment caused a 57% reduction in Vero cell cytotoxic activity of VT2. As shown in Table 1, treatment of VT2 with the antibody promoted a 38% reduction in the effect of VT2 on neutrophil apoptosis (P < 0.01). LPS is well known to be heat resistant, while VT2 is sensitive. Thus, purified VT2 (0.02 U/ml) was treated at 60°C for 15 min, and the inhibitory effect on neutrophil apoptosis was determined. Heat inactivation of VT2 significantly abolished the effect of VT2 on neutrophil apoptosis (P < 0.01). In order to confirm the inhibitory effect of VT2 on neutrophil apoptosis, we evaluated the biological effect of recombinant VT2 (rVT2) on neutrophil apoptosis. rVT2 exerted verocytotoxic activity at 0.08 U/μg of protein, and contamination by LPS was shown to be less than 1.2 × 10−5 EU/μg. As shown in Table 1, rVT2 at 0.1 U/ml significantly inhibited spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis (P < 0.01). These data indicate that the effect of VT2 on neutrophil apoptosis is LPS independent.

TABLE 1.

Effects of anti-VT2 antibody, heat treatment, and metabolic inhibitors on the VT2-induced delay in neutrophil apoptosis

| Expt | Treatmenta | % Apoptosisb |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | 64.2 ± 5.4 |

| VT2 | 25.4 ± 4.8 | |

| rVT2 | 28.2 ± 5.7 | |

| VT2 + anti-VT2 | 49.6 ± 6.8* | |

| Heat-treated VT2 | 60.7 ± 4.3* | |

| 2 | None | 61.8 ± 3.2 |

| VT2 | 27.6 ± 5.6 | |

| VT2 + staurosporine | 56.8 ± 2.6* | |

| VT2 + genystein | 31.7 ± 4.5 | |

| VT2 + H-89 | 29.4 ± 6.1 |

Neutrophils (2 × 106) were incubated with anti-VT2 antibody-treated VT2 or heat-treated VT2 for 24 h. In experiment 2, neutrophils were pretreated with various metabolic inhibitors for 30 min at 37°C and subsequently cells were incubated with VT2 for 24 h. After incubation, apoptotic cells were detected by a FACScan flow cytometer.

Data are percentages of apoptotic cells and represent means and standard deviations (three replicates/group) of a representative of four experiments performed with neutrophils isolated from independent donors. Asterisks represent P values of <0.01 compared with VT2.

Effects of metabolic inhibitors on the VT2-induced delay in neutrophil apoptosis.

In order to evaluate the mechanisms of VT2 action, neutrophils were incubated with VT2 (0.02 U/ml) for 24 h in the presence and absence of various metabolic inhibitors. A potent inhibitor of protein kinase C (PKC), staurosporine at 100 nM, significantly restored the inhibitory effect of VT2 (P < 0.01), indicating possible involvement of the PKC pathway in VT2-treated cells (Table 1). In contrast, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, genystein at 50 μg/ml, and a selective inhibitor of protein kinase A, H-89 at 20 μM, failed to prevent the effect of VT2.

Conclusions.

In the present study, we have provided evidence for the first time that VT2 derived from E. coli O157:H7 inhibits spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis in a time- and dose-dependent manner and that the PKC pathway may be involved in VT2-treated cells.

VT was first identified as a cytotoxin for Vero cells (6, 8, 9). Subsequent studies have demonstrated that VTs are capable of inducing cellular death in various types of cells (12, 21). In contrast, the cytotoxic effect of VT1 on monocytes and macrophages was negligible. Recent studies have shown that VT1 is capable of stimulating macrophages or monocytes to produce various cytokines (16, 18, 22). Increased production of proinflammatory cytokines may contribute to the development of inflammatory responses in VTEC-associated diseases. Based on this evidence and the results of this study, it seems reasonable to suppose that VTs exert stimulatory effects on inflammatory leukocytes and promote longer survival through the prevention of apoptosis. The VT2-induced delay in neutrophil apoptosis may enhance inflammation and result in aggravation of neutrophil-mediated tissue damage in VTEC-associated diseases. We have demonstrated that a specific inhibitor of PKC abrogates the effect of VT2 on neutrophil apoptosis. Although the activation of PKC in VT2-treated neutrophils has not yet been directly demonstrated, our results indicate that PKC may be involved in the VT2-induced delay in neutrophil apoptosis.

Further investigation should be directed toward the in vivo effects of VT2 on neutrophil apoptosis. Elucidation of the precise roles of VTs in VTEC-associated diseases may provide therapeutic advantages against these diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fumio Gondaira (Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan) for providing rVT2.

REFERENCES

- 1.Argyle J C, Hogg R T, Pysher T J, Silva F G, Siegler R L. A clinicopathological study of 24 children with hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 1990;4:52–58. doi: 10.1007/BF00858440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brach M A, deVos S, Gruss H-J, Herrmann F. Prolongation of survival of human polymorphonuclear neutrophils by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor is caused by inhibition of programmed cell death. Blood. 1992;80:2920–2924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandra B, Louis C, Obrig T. Specific interaction of E. coli O157:H7-derived Shiga-like toxin 2 with human renal endothelial cells. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1397–1401. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.5.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forsyth K D, Simpson A C, Fitzpatrick M M, Barratt T M, Levinsky R J. Neutrophil-mediated endothelial injury in haemolytic uremic syndrome. Lancet. 1989;ii:411–414. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90591-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Habib R, Levy M, Gagnadoux M F, Broyer M. Prognosis of the hemolytic uremic syndrome in children. Adv Nephrol. 1982;11:99–128. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inward C D, Willias J, Chant I, Crocker J, Milford D V, Rose P E, Taylar C M. Verotoxin-1 induces apoptosis in vero cells. J Infect. 1995;30:213–218. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(95)90693-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson M P, Neill R J, O'Brien A D, Holmes R K, Newland J W. Nucleotide sequence analysis and comparison of the structural genes for Shiga-like toxin 1 and Shiga-like toxin 2 encoded by bacteriophages from Escherichia coli 933. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;44:109–114. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konowalchuk J, Speirs J I, Stavric S. Vero response to a cytotoxin of Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1977;18:775–782. doi: 10.1128/iai.18.3.775-779.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lingwood C A, Law H, Richardson S, Petric M, Brunton J L, Grandis S D, Karmai M A. Glycolipid binding of purified and recombinant Escherichia coli produced verotoxin in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:8834–8843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louise C B, Obrig T G. Shiga toxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome: combined cytotoxic effects of Shiga toxin, interleukin-1β, and tumor necrosis factor alpha on human vascular endothelial cells in vitro. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4173–4179. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.4173-4179.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macleod D L, Gyles C L. Purification and characterization of an Escherichia coli Shiga-like toxin 2 variant. Infect Immun. 1990;18:775–779. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.5.1232-1239.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahan J D, McAllister C, Karmali M. Verotoxin-1 induction of apoptosis in human glomerular capillary endothelial cells (GCEC) in vitro is dependent on cytokines, cell confluence, and cell cycle. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7:1661. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morigi M, Micheletti G, Figliuzzi M, Imberti B, Karmali M A, Remuzzi A, Zoja C. Verotoxin-1 promotes leukocyte adhesion to cultured endothelial cells under physiologic flow conditions. Blood. 1995;86:4553–4558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicoletti I, Migliorati G, Pagliacci M C, Grignani F, Riccardi C. A rapid and simple method for measuring thymocyte apoptosis by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 1991;139:271–279. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90198-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ottonello L, Gonella R, Dapino P, Sacchetti C, Dallegri F. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits apoptosis in human neutrophils: role of intracellular cyclic AMP levels. Exp Hematol. 1998;26:895–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramegowda B, Tesh V L. Differentiation-associated toxin receptor modulation, cytokine production, and sensitivity of Shiga-like toxin in human monocytes and monocytic cell lines. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1173–1180. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1173-1180.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Savill J S, Wyllie A H, Henson J E, Walport M J, Heson P M, Haslett C. Macrophage phagocytosis of aging neutrophils in inflammation. J Clin Investig. 1989;83:865–875. doi: 10.1172/JCI113970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Setten P A V, Monnerns L A H, Verstraten R G G, van den Heuvel L P W J, van Hinsbergh V W M. Effects of verotoxin-1 on nonadherent human monocytes: binding characteristics, protein synthesis, and induction of cytokine release. Blood. 1996;88:174–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strockbine N A, Marques L R M, Newland J W, Smith H W, Holmes R K, O'Brien A D. Two toxin-converting phages from Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain 933 encode antigenically distinct toxins with similar biologic activities. Infect Immun. 1986;53:135–140. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.1.135-140.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sweeney J F, Nguyen P K, Omann G M, Hinshaw D B. Lipopolysaccharide protects polymorphonuclear leukocytes from apoptosis via tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent signal transduction pathways. J Surg Res. 1998;74:64–70. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1997.5193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taga S, Carlier K, Mishal Z, Capoulade C, Mangeney M, Lecluse Y, Coulaud D, Tetaud C, Pritchard L L, Tursz T, Wiels J. Intracellular signaling events in CD77-mediated apoptosis of Burkitt's lymphoma cells. Blood. 1997;90:2757–2767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tesh V L, Ramegowda B, Samuel J E. Purified Shiga-like toxins induce expression of proinflammatory cytokines from murine peritoneal macrophages. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5085–5094. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.5085-5094.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]