Abstract

Background

Talaromyces marneffei (T. marneffei) is a temperature‐dependent dimorphic fungus that is mainly prevalent in Southeast Asia and South China and often causes disseminated life‐threatening infections. This study aimed to investigate the clinical features and improve the early diagnosis of talaromycosis marneffei in nonendemic areas.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed the medical records of six cases of T. marneffei infection. We describe the clinical manifestations, laboratory tests, and imaging manifestations of the six patients.

Results

Talaromyces marneffei infection was confirmed by sputum culture, blood culture, tissue biopsy, and metagenomic next‐generation sequencing (mNGS). In this study, there were five disseminated‐type patients and two HIV patients. One patient died within 24 h, and the others demonstrated considerable improvement after definitive diagnosis.

Conclusions

Due to the lack of significant clinical presentations of talaromycosis marneffei, many cases may be easily misdiagnosed in nonendemic areas. It is particularly important to analyze the imaging manifestations and laboratory findings of infected patients. With the rapid development of molecular biology, mNGS may be a rapid and effective diagnostic method.

Keywords: disseminated Talaromyces marneffei infection, laboratory test, metagenomic next‐generation sequencing, Talaromyces marneffei, talaromycosis marneffei

Chest CT images among patients infected with Talaromyces marneffei. (A) The blue arrow indicates enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes (mediastinal window).

1. INTRODUCTION

Talaromyces marneffei is a rare pathogenic thermally dimorphic fungus that grows as mold at 25°C and as yeast at 37°C. 1 The resistance of the host to invasion by T. marneffei may be based on cellular immunity, with the T‐cell‐mediated Thl‐type response pattern playing an important role in the defense of the host against fungal infection. 2 It mainly invades the human monocyte–macrophage system and causes infections in patients with immune dysfunction (e.g., immunosuppressed, immunocompromised, or immunodeficient patients). The disease is predominant in Guangxi, Hong Kong, and Taiwan but rare in the city of Ningbo in Zhejiang Province. 3 , 4 It has become the most common opportunistic fungal infection in Southeast Asia (especially in AIDS patients). 5 However, in recent years, there have been increasing reports of cases among non‐HIV‐infected patients. 6 In this article, we describe the clinical and laboratory features of six patients.

2. METHODS

2.1. Clinical data

This was a retrospective study that used data collected from medical records. Six patients were diagnosed and treated at the Ningbo First Hospital, and the patient's inpatient medical records were reviewed. Related data included demographic information (age and sex), clinical features (with or without underlying disease), laboratory data, imaging findings, treatment, and prognoses. The clinical data of the patients are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Clinical features and laboratory findings of six patients with Talaromyces marneffei infection

| Clinical features | Number of cases (n = 6) | Laboratory findings | Number of cases (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fever | 6 | CRP increase | 6 |

| Cough | 3 | Leukocytosis | 4 |

| Dyspnea | 2 | Achroacytosis | 4 |

| Weight loss | 3 | Hemoglobin decrease | 5 |

| Anemia | 6 | Thrombocytopenia | 3 |

| Hepatomegaly or splenomegaly | 2 | Thrombocytosis | 2 |

| Chest pain | 1 | Elevated creatinine | 2 |

| Skin lesion | 2 | Elevated ALT | 2 |

| Malaise | 4 | Elevated AST | 2 |

| Fungemia | 5 | Albumin decrease | 4 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 1 | Elevated ESR | 6 |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CRP, C‐reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

2.2. Laboratory tests

Routine blood examination, HIV antibody, C‐reactive protein (CRP), blood coagulation, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and blood biochemistry tests were performed with standardized testing equipment and kits.

2.3. Identification methods of T. marneffei

There were three methods used for pathogen examination.

2.3.1. Pathogen culture

Cultures of clinical specimens, including blood, sputum, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, were established on Sabouraud agar medium at 25°C and 37°C. Identification was based upon the morphology of the colonies. At 25°C, T. marneffei grew as a mold and created a soluble red pigment that diffused into the agar. At 37°C, it developed as a yeast.

2.3.2. Microscopy observation

Talaromyces marneffei was identified by cytology and histopathology from clinical specimens by hexamine silver staining and Wright–Giemsa staining.

2.3.3. Metagenomic next‐generation sequencing

The metagenomic next‐generation sequencing (mNGS) method is based on the Illumina sequencing platform and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) free library building technology. In this study, clinical specimens were sent to specialized testing institutions for different sample processing procedures. This approach mainly includes specimen pretreatment, nucleic acid extraction, library preparation, online sequencing, database matching, and interpretation of results.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Clinical manifestation

Six patients were diagnosed and treated at the Ningbo First Hospital, all of whom had lived in Ningbo for a long time. There were two female and four male patients, and all had no epidemiological history and no history of exposure to bamboo rats. The median age of the patients was 60 years.

The most common clinical symptoms of patients infected with T. marneffei were fever and anemia, followed by fungemia, malaise, respiratory symptoms, and weight loss (Table 2). The primary presentation for one patient was gastrointestinal symptoms (such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloody stools). Five patients exhibited disseminated T. marneffei infections; three patients had primary lesions in the lungs, and two patients presented with subcutaneous nodules or abscesses (Table 1). All had various underlying diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, multiple myeloma, diabetes, and HIV. Notably, four cases were initially misdiagnosed as pneumonia or pulmonary tuberculosis.

TABLE 2.

Clinical features of patients with talaromycosis marneffei

| Patient | Gender | Age | Proposed diagnosis | Symptom | Underlying illness | Hormone immunosuppressant use | Imaging findings | Identification methods of TM | Treatments | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case1 | M | 63 | COPD; interstitial pulmonary disease; severe pneumonia; acute respiratory failure; anemia | Cough and sputum; fever; anemia; malaise; occasional chest tightness and shortness of breath | COPD; interstitial pulmonary disease | Inhaled corticosteroids for many years | High‐density mass‐like shadow next to the right hilum; multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the mediastinum; emphysema; fibrosis with interstitial lesions | Culture of sputum and BALF | Tracheal cannula, piperacillin/tazobactam + meropenem prior to diagnosis. Post‐diagnosis voriconazole | Cured |

| Case2 | M | 28 | HIV; hypoproteinemia; anemia; thrombocytopenia | Gastrointestinal bleeding | HIV | No | Normal | Blood smear examination by microscopy | No antifungal medication | Death within 24 h of admission |

| Case3 | M | 80 | Infectious pneumonia; paroxysmal atrial fibrillation; hypertension; type 2 diabetes mellitus; anemia; hypoproteinemia | Recurrent fever; cough and sputum | Diabetes | No | Infectious lesions in both lungs, enlarged left hilar shadow, and mildly enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes | BALF mNGS; sputum culture; Blood mNGS | Piperacillin‐tazobactam + moxifloxacin + empirical anti‐tuberculosis prior to diagnosis; post‐diagnosis voriconazole | Relapsed |

| Case4 | F | 57 | Multiple myeloma; infectious fever; anemia | Fever; dizziness; diarrhea and abdominal pain | Multiple myeloma | Long‐term high‐dose hormone therapy (during bone marrow transplantation) | A little chronic inflammation in both lungs, a small amount of pleural effusion, and an enlarged spleen | Blood mNGS, intestinal lesion mNGS | Imipenem + caspofungin + vancomycin prior to diagnosis; post‐diagnosis amphotericin + voriconazole | Recovered |

| Case5 | M | 48 | HIV; hypertension; chronic kidney disease stage 3; pneumonia (possible Pneumocystis carinii infection) | Fever; cough; coughing sputum | HIV | No | Inflammation of both lungs considered | Blood culture | Ceftriaxone + sulfamethoxazole and transferred to another hospital before diagnosis | Recovered (follow‐up) |

| Case6 | F | 79 | Acute myocardial infarction; acute heart failure; respiratory failure; pulmonary infection; type 2 diabetes; hypertension; anemia | Chest tightness and chest pain with shortness of breath | Diabetes | No | Left pleural effusion and a little inflammation in the left lower lung | Blood culture | Piperacillin‐tazobactam and transferred to another hospital before diagnosis | Cured (follow‐up) |

Note: Cured: the resolution of all symptoms and mycological eradication; Recovered: improvement in most signs and symptoms; Relapsed: no clinical improvement, clinical condition deterioration, or death.

Abbreviations: BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; F, female; M, male; TM, talaromycosis marneffei.

3.2. Laboratory tests

C‐reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were significantly elevated in six patients, and the white blood cell count was increased in four patients and decreased in one patient. In addition, five patients had varying degrees of anemia, all below 100 g/L; four patients had varying degrees of decreased albumin, with the lowest value being 22.4 g/L; and three patients were tested for lymphocyte subpopulation, which reflected low immune function in two patients and normal immune function in the other (Table 3). Two patients tested positive for HIV antibody (primary screening) and were diagnosed with HIV infection by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Three patients had no significant abnormalities in liver and kidney function.

TABLE 3.

Analysis of lymphocyte subsets in three patients with talaromycosis marneffei

| Patients | CD3 | CD4 | CD8 | CD4/CD8 | NK | CD19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P3 | 65.57% | 39.72% | 27.23% | 1.5 | 27.09% | 6.31% |

| P4 | 71.05% | 22.42% | 46.72% | 0.48 | 29.01% | O.31% |

| P5 | 86.83% | 2.14% | 84.05% | 0.03 | 14.21% | 0.36% |

Note: Normal ranges: CD3: 58.4%–81.56%; CD4: 31%–60%; CD8: 13%–41%; CD4/CD8: 0.8–4.2; NK: 14%–40%; CD19: 5%–25%.

3.3. Imaging and other examinations

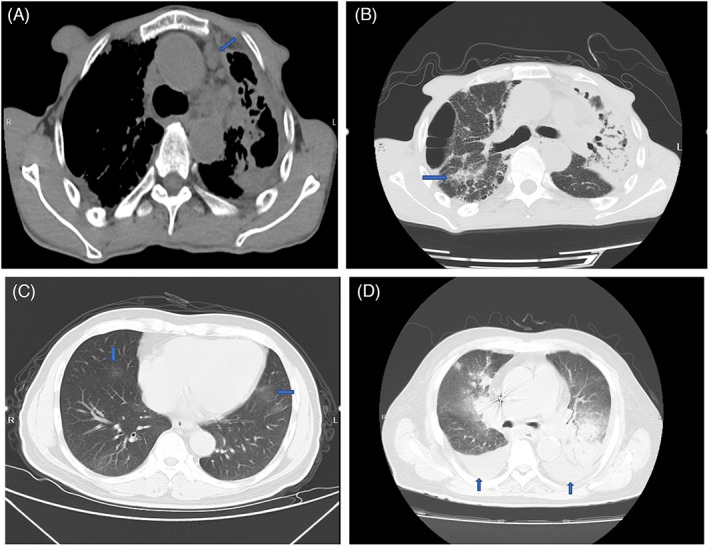

Among six patients, chest imaging showed abnormal lesions in the lungs of five patients for the first time (Table 4). There were multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the mediastinum and pulmonary hila in two patients (Figure 1A), multiple high‐density plaques and strips in two patients (Figure 1B), multiple patchy ground‐glass opacities in one patient (Figure 1C), and bilateral pleural effusion in three patients (Figure 1D).

TABLE 4.

High‐resolution computed tomography among six patients infected with Talaromyces marneffei.

| Items | Number of cases (n = 6) |

|---|---|

| Normal | 1 |

| High‐density plaque/ strip | 2 |

| Interstitial infiltration | 1 |

| Alveolar infiltration | 4 |

| Nodule | 1 |

| Pleural effusion | 2 |

| Hilar/mediastinum lymphadenopathy | 2 |

FIGURE 1.

Chest CT images among patients infected with Talaromyces marneffei. (A) The blue arrow indicates enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes (mediastinal window). (B) The blue arrow indicates high‐density plaque and strip. (C) Blue arrows indicate multiple patchy ground‐glass opacities. (D) Blue arrows indicate bilateral pleural effusion.

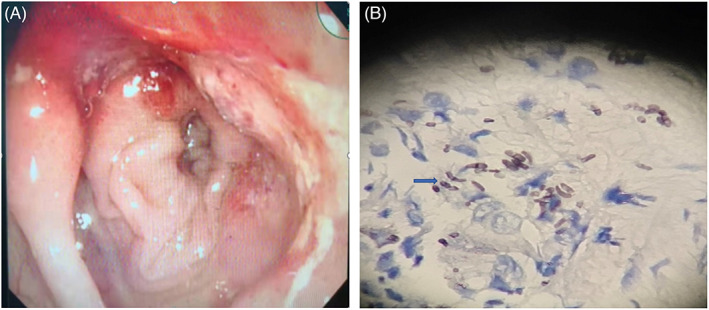

Case 4 was diagnosed with talaromycosis marneffei involving the gastrointestinal tract. A colonoscopy revealed colon erosion, hyperemia, edema, and multiple intestinal mucosal ulcers (Figure 2A). Mucosal biopsy of transverse colon and descending colon tissue was performed (Figure 2B). After a period of antifungal treatment at our hospital, a repeat colonoscopy showed multiple ulcers in the colon in the healing stage, which indicated that the patient's condition had improved.

FIGURE 2.

Colonoscopy and histopathological examination. (A) The mucosa had apparent hyperemia and edema, as well as scattered erosion and ulceration, according to a colonoscopy. (B) Colon mucosa was stained with hexamine silver staining, showing several yeast‐like organisms with septate forms (indicated by the blue arrow).

3.4. Diagnosis of patients with talaromycosis marneffei

Six cases were diagnosed with talaromycosis marneffei by culture of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and sputum specimens, blood microscopy, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid mNGS, intestinal lesion mNGS, and blood mNGS.

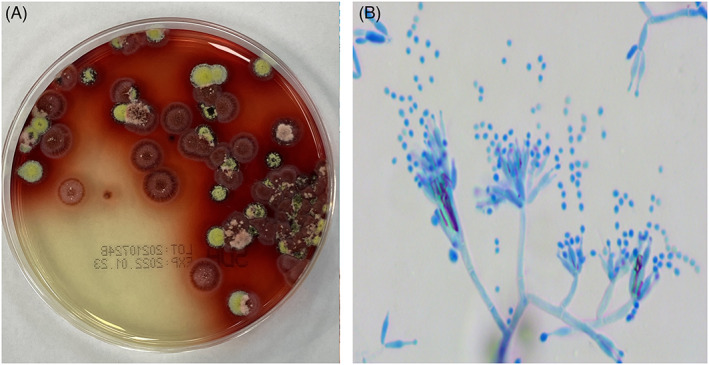

3.4.1. Culture and microscopy observation

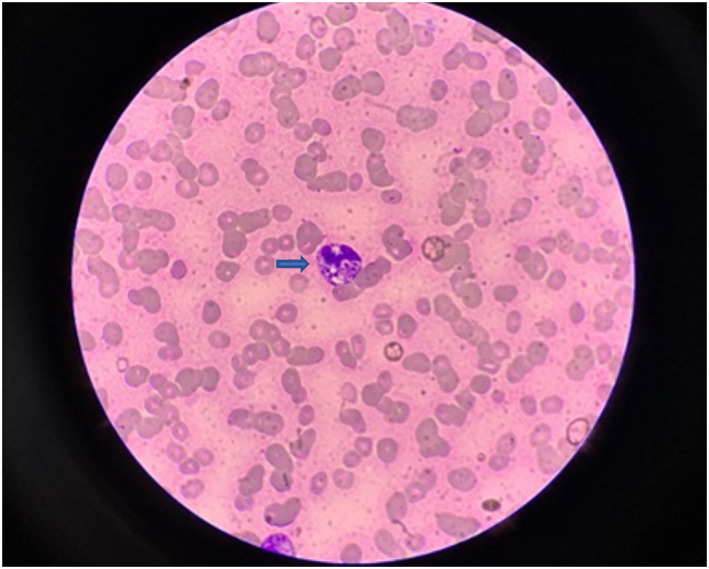

The specimens were inoculated into Sabouraud agar medium and incubated at 25°C and 37°C. The fungus appeared as a mold with red wine pigment at 25°C (Figure 3A), and curved conidial chains were evident under the microscope. The cultures were stained with lactophenol cotton blue, which revealed smooth transparent branched separated mycelia typical of broom‐like branches, with multiple scattered nonparallel peduncle bases with 2–10 vial peduncles on them and narrowed apically with scattered single chains of conidia (Figure 3B). It grew as yeast without pigment yield at 37°C, and fungal cells under the microscope presented as round or oval‐shaped yeast‐like cells with a diameter of 3 μm (Figure 2B). The fungus was identified by its characteristics. Peripheral blood smear was selected for direct microscopic examination after Wright–Giemsa staining. Round, oval, or sausage‐shaped mounded or scattered organisms could be seen in neutrophils and macrophages (Figure 4).

FIGURE 3.

Culture and microscopy observation of Talaromyces marneffei. (A) Morphology and wine pigment of T. marneffei colonies from alveolar lavage fluid culture on Sabouraud agar medium for 7 days at 25°C. (B) Typical broom‐shaped, branching septate hyphae of T. marneffei at 25°C with lactophenol cotton blue staining (×400).

FIGURE 4.

Blood smear examination. Blood smears were stained with Wright‐Giemsa staining, which showed small round‐to‐ovoid yeast cells within the neutrophil cytoplasm. Yeast cells were unevenly stained and showed strong staining at one end (indicated by the blue arrow) (×1000).

3.4.2. Metagenomic next‐generation sequencing

Among six patients, only two patients were diagnosed with talaromycosis marneffei by mNGS. Due to exacerbation of the condition and multiple negative sample cultures, clinicians collected related samples for mNGS. mNGS of the BALF of case 3 revealed 38 T. marneffei reads, and mNGS of the intestinal lesion of case 4 revealed 27,935 T. marneffei reads. In addition, the presence of T. marneffei was also detected in their blood by mNGS (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Microorganism detected by mNGS of two patients

| Sample | Patient | Bacteria | Reads | Fungi | Reads | Virus | Reads |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BALF | P3 | Klebsiella pneumonia | 28 | Talaromyces marneffei | 38 | Human betaherpesvirus 5 | 2 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 20 | Candida albicans | 5 | ||||

| Blood | P3 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 66 | Talaromycesmarneffei | 1 | Human betaherpesvirus 5 | 159 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 4 | Human gammaherpesvirus 4 | 7 | ||||

| Blood | P4 | Cutibacterium acnes | 2 | Talaromyces marneffei | 784 | Human betaherpesvirus 5 | 22 |

| Moraxella osloensis | 1 | ||||||

| Lesion of intestine | P4 | Staphylococcus haemolyticus | 16 | Talaromyces marneffei | 27,935 | ||

| Enterococcus faecalis | 15 | Candida glabrate | 2987 | ||||

| Cutibacterium acnes | 12 | Malassezia globosa | 44 | ||||

| Prevotella melaninogenica | 4 | ||||||

| Moraxella osloensis | 3 |

Abbreviations: BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; mNGS, metagenomic next‐generation sequencing.

4. TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

Amphotericin B, itraconazole, and voriconazole are routinely utilized for talaromycosis marneffei in clinical treatment. In terms of clinical response and fungicidal action, amphotericin B was superior to itraconazole in the initial treatment. 7 Voriconazole was reported to be effective for disseminated T. marneffei infection. 8 Thus, most of the cases in this study were treated with intravenous amphotericin B at a dose of 0.6 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks, followed by intravenous voriconazole at a dose of 200 mg/day for maintenance therapy. One mild case was treated with intravenous voriconazole at a dose of 200 mg q12 h for the first 24 h, followed by oral therapy at 200 mg twice daily. To reduce the incidence of adverse effects, liver function, renal function, and body electrolytes were monitored closely and regularly during treatment.

During the treatment period, adverse drug reactions to amphotericin B were observed. Two cases showed elevated creatinine levels. These patients were treated with lower doses of amphotericin B, or the drug was discontinued and replaced with voriconazole therapy. Only one patient did not receive antifungal medication and died within 24 h of admission due to deterioration of the disease. During the 6‐month follow‐up, most of the cases in this study showed improvement after treatment and had a good prognosis. One case is still under treatment and follow‐up.

5. DISCUSSION

Talaromyces marneffei is a species of penicillium isolated from the liver of bamboo rats that died unnaturally in Vietnam in 1956. In 1959, the fungus was named Penicillium marneffei in honor of Hubert Marneffe, the director of the Pasteur Institute in Indochina. 9 In 2011, based on phylogenetic and phenotypic analysis, the name was changed to T. marneffei. 10 Bamboo rats are currently considered natural hosts or carriers of this pathogen. 11 Regarding the patients' epidemiological history, it was found that no patients had a history of residence in endemic areas or exposure to bamboo rats. The original route of infection is currently unknown, but it could be through skin lesions or conidia inhalation. It has been documented that T. marneffei enters the blood system by invading the reticuloendothelial system and then spreads to other organs through the lymphatic system and blood circulation. 12 , 13 T. marneffei mainly invades organs and sites related to the monocyte–macrophage reticuloendothelial system. T. marneffei infections can be divided into disseminated and focal types; focal type infections are often confined to the site of invasion, and the clinical manifestations are dominated by the symptoms of the original disease. The disseminated type often involves multiple tissues and organs. Common clinical manifestations of disseminated T. marneffei include fever, respiratory signs, anemia, weight loss, skin lesions, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly. 3 In this study, five patients exhibited disseminated T. marneffei infections. These patients presented with fever, cough, lymph node enlargement, anemia, and gastrointestinal symptoms, all of which were nonspecific and led to a misdiagnosis of tuberculosis or other fungal infections. Skin lesions are a clinical feature of disseminated T. marneffei, and characteristic lesions are papules with central necrosis. 9 Two patients in our cohort presented with atypical skin lesions, such as subcutaneous nodules or abscesses. In three cases, the lungs were affected by fungal invasion first. In addition, the possibility of gastrointestinal infection was not excluded. Although lymphoid tissue is extensive throughout the digestive tract, talaromycosis marneffei infection of the intestine is uncommon. 13 The atypical and nonspecific clinical presentation of fungal infections in T. marneffei often adds to the difficulty of early diagnosis, resulting in diagnostic delay and increased mortality.

T lymphocyte cells are critical for controlling T. marneffei infection. 14 Some experiments have indicated that CD4+ T cells mediate significant pulmonary inflammatory infiltration in mice by recruiting macrophages and granulocytes. CD4 deficiency may lead to the loss of Th2 anti‐inflammatory cytokines (IL‐4, IL‐5, and IL‐10). 15 In the innate immune system, activated macrophages can activate some proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. 16 Myeloperoxidase‐dependent neutrophils also have fungicidal activity through the actions of reactive oxygen species. 17 In HIV‐positive individuals, T. marneffei‐activated monocyte‐derived dendritic cells (MDDCs) may further accelerate immunosuppression by promoting HIV‐1 transfection of CD4+ T cells. 18 Overall, the inflammatory and regulatory responses to a fungal infection are significantly modulated by the innate and acquired immune systems. Lymphocyte subpopulation analysis should be performed in clinical work, especially in immunosuppressed or HIV‐positive patients.

The pathogenesis of T. marneffei involves the ability of the fungus to avoid being killed by macrophages and replicate inside them. 19 T. marneffei can produce melanin or melanin‐like compounds to enhance resistance to phagocytosis by macrophages. 20 After phagocytosis by macrophages, T. marneffei (as an intracellular yeast form) induces the production of superoxide dismutase and catalase‐peroxidase in response to oxidative stress. 19 Other factors may also be associated with the pathogenicity of T. marneffei, including heat shock proteins (Hsp70 and Hsp30), 19 secreted galactomannan protein Mp1p 21 and the expression of isocitrate lyase. 22 Subsequently, conidial replication and establishment of infection mediate disseminated infections.

The incidence of infection in HIV‐negative patients is increasing. For example, in 2012, Yongxuan Hu reviewed 668 cases of talaromycosis marneffei in mainland China from January 1984 to December 2009, and there were 82 (12.3%) HIV‐negative infected patients. 3 In 2015, Ye Qiu retrospectively analyzed 109 patients admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University for talaromycosis marneffei from January 1, 2003, to August 1, 2014, 39.45% of whom were HIV‐negative. 23 In HIV‐negative individuals, infection factors are most likely attributed to underlying conditions, including immunodeficiency due to anti‐IFN‐γ autoantibodies, immunosuppressive therapy, malignancy, diabetes mellitus, and organ transplantation. 24 Anti‐IFN‐γ autoantibodies can inhibit STAT1 phosphorylation and IL‐12 production, increasing the risk of fungal infection. 25 Other predisposing factors may be related to lymphocyte depletion and impairment of lymphocyte proliferation. Interestingly, one of our cases was an immunocompetent patient, and the infection factor was most likely attributed to the patient's diabetes (Table 2).

In terms of laboratory tests, all patients had elevated serum CRP levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rates (Table 1). Some patients had liver damage, characterized by elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST), especially severe patients. HIV‐positive patients were more likely to have leukopenia, low platelet counts, elevation of alanine transaminase, and positive blood cultures. In addition, the chest imaging manifestations of patients with T. marneffei infection were diverse, including multiple patches or large consolidations, ground‐glass opacities, pleural effusion, and hilar and mediastinal lymph node enlargement (Table 1). Infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, Aspergillus pneumonia, lymphoma, lung cancer, and others should be ruled out. 26

The traditional methods for diagnosis of talaromycosis marneffei include culture of the pathogen and histopathological examination. 1 However, the culture positivity rate was not high in patients with early infection. These sample culture results were presented as repeated negative, including a blood culture of case 3 and a stool culture of case 4. Among the six cases, two were diagnosed with talaromycosis marneffei by mNGS. One case was diagnosed with talaromycosis marneffei by examination of a peripheral blood smear (Figure 4). Yeast‐like organisms may be seen on the blood smear, especially in patients with heavy fungemia. 27 Blood culture was positive in only two patients in our study (Table 2). Whereas it usually takes 3–10 days for a patient's clinical specimen to be cultured for T. marneffei, the time from admission to diagnosis was long for most patients in our study. During this period, some patients were misdiagnosed with bacterial pneumonia or other diseases. Moreover, they received improper treatment. When none of their conditions improved significantly, physicians began to suspect the initial diagnosis and considered mNGS. Other techniques, such as novel Mp1p enzyme immunoassay and the beta‐D‐glucan test, have a certain role in the auxiliary diagnosis of talaromycosis marneffei. 28 , 29 However, these approaches have the drawbacks of extensive processes and limited sensitivity. Several real‐time PCR techniques to identify T. marneffei have been developed in response to the demand for faster and more sensitive diagnostics, although these are limited to primer and probe design. 30 , 31 Under such circumstances, the implementation of NGS in the clinical field might have some undeniable advantages.

mNGS, a rapid and effective diagnostic approach, can obtain information on microbial species and abundance in samples by high‐throughput sequencing of nucleic acids and bioinformatics analysis. 32 It not only comprehensively identifies pathogens but also offers a significantly reduced time requirement for pathogen identification. In this study, clinicians chose mNGS in the following situations: (1) difficulty identifying fungal pathogens despite repeated cultures and (2) a need for early and precise diagnosis in patients with severe pathogenic infections. Multiple studies have reported the use of mNGS in clinical fungal diagnosis, which also reveals the potential merits of this technique in rapid etiological diagnosis. 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 However, there are some shortcomings in the widespread application of mNGS, such as high cost and a lack of recognized standards in this area.

Talaromycosis marneffei is an uncommon disease that causes high mortality rates. A previous study showed that HIV infection, CD4/CD8 < 0.5, a reduced percentage of CD4+ T cells and late diagnosis were potential risk factors for poor prognosis. 37 Late diagnosis is the leading cause of death in T. marneffei‐infected individuals. 38 It is clear that early and rapid diagnosis is particularly important. Therefore, clinicians should consider talaromycosis marneffei if a patient has suffered recurrent fever; multiple patches, nodules, or masses in the lungs; gastrointestinal symptoms; and characteristic skin lesions, especially if anti‐inflammatory treatment is ineffective. Pathogen cultivation and other relevant laboratory tests are essential. In addition, we recommend the early use of mNGS to reduce mortality and prolong survival time. There are some limitations of this study. First, it is a retrospective cohort study, and the limited number of cases makes it difficult to explore the differences in clinical manifestations between HIV‐positive and HIV‐negative populations. Second, there is a lack of comprehensive analysis of the infection mechanism of T. marneffei in nonendemic areas.

In conclusion, we analyzed six cases of talaromycosis marneffei in nonendemic areas in the hope of promoting awareness and familiarity with this rare disease among more clinicians in nonendemic areas and improving the prognosis of patients.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Lei Peng and Xing‐bei Weng. The first draft of the article was written by Lei Peng, and all authors commented on previous versions of the article. All authors read and approved the final article.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by the Ningbo Natural Science Foundation (2019A610381) and the Ningbo Public Welfare Foundation (2019C50087).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the colleagues in the clinical microbiology laboratory, Ningbo First Hospital, for the suggestions for preparing the article.

Peng L, Shi Y‐b, Zheng L, Hu L‐q, Weng X‐b. Clinical features of patients with talaromycosis marneffei and microbiological characteristics of the causative strains. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022;36:e24737. doi: 10.1002/jcla.24737

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zhou F, Bi X, Zou X, Xu Z, Zhang T. Retrospective analysis of 15 cases of Penicilliosis marneffei in a southern China hospital. Mycopathologia. 2014;177(5–6):271‐279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee PP, Chan KW, Lee TL, et al. Penicilliosis in children without HIV infection—are they immunodeficient? Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(2):e8‐e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hu Y, Zhang J, Li X, et al. Penicillium marneffei infection: an emerging disease in mainland China. Mycopathologia. 2013;175(1–2):57‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shen Q, Sheng L, Zhang J, Ye J, Zhou J. Analysis of clinical characteristics and prognosis of talaromycosis (with or without human immunodeficiency virus) from a non‐endemic area: a retrospective study. Infection. 2022;50(1):169‐178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wong SYN, Wong KF. Penicillium marneffei infection in AIDS. Patholog Res Int. 2011;2011:764293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chan JF, Lau SK, Yuen KY, Woo PC. Talaromyces (Penicillium) marneffei infection in non‐HIV‐infected patients. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2016;5(3):e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Le T, Kinh NV, Cuc NTK, et al. A trial of itraconazole or amphotericin B for HIV‐associated talaromycosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(24):2329‐2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ouyang Y, Cai S, Liang H, Cao C. Administration of voriconazole in disseminated Talaromyces (Penicillium) marneffei infection: a retrospective study. Mycopathologia. 2017;182(5–6):569‐575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cao C, Xi L, Chaturvedi V. Talaromycosis (Penicilliosis) Due to Talaromyces (Penicillium) marneffei: Insights into the clinical trends of a major fungal disease 60 years after the discovery of the pathogen. Mycopathologia. 2019;184:709‐720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Samson RA, Yilmaz N, Houbraken J, et al. Phylogeny and nomenclature of the genus Talaromyces and taxa accommodated in Penicillium subgenus biverticillium. Stud Mycol. 2011;70(1):159‐183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cao C, Liang L, Wang W, et al. Common reservoirs for Penicillium marneffei infection in humans and rodents, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(2):209‐214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang YG, Cheng JM, Ding HB, et al. Study on the clinical features and prognosis of penicilliosis marneffei without human immunodeficiency virus infection. Mycopathologia. 2018;183:551‐558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pan M, Huang J, Qiu Y, et al. Assessment of Talaromyces marneffei infection of the intestine in three patients and a systematic review of case reports. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(6):ofaa128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kudeken N, Kawakami K, Kusano N, Saito A. Cell‐mediated immunity in host resistance against infection caused by Penicillium marneffei . J Med Vet Mycol. 1996;34(6):371‐378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huffnagle GB, Lipscomb MF, Lovchik JA, Hoag KA, Street NE. The role of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the protective inflammatory response to a pulmonary cryptococcal infection. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;55(1):35‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dong RJ, Zhang YG, Zhu L, et al. Innate immunity acts as the major regulator in Talaromyces marneffei coinfected AIDS patients: cytokine profile surveillance during initial 6‐month antifungal therapy. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(6):ofz205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ellett F, Pazhakh V, Pase L, et al. Macrophages protect Talaromyces marneffei conidia from myeloperoxidase‐dependent neutrophil fungicidal activity during infection establishment in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14(6):e1007063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Qin Y, Li Y, Liu W, et al. Penicillium marneffei‐stimulated dendritic cells enhance HIV‐1 trans‐infection and promote viral infection by activating primary CD4+ T cells. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pongpom M, Vanittanakom P, Nimmanee P, Cooper CR Jr, Vanittanakom N. Adaptation to macrophage killing by Talaromyces marneffei . Future Sci OA. 2017;3(3):FSO215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu D, Wei L, Guo T, Tan W. Detection of DOPA‐melanin in the dimorphic fungal pathogen Penicillium marneffei and its effect on macrophage phagocytosis in vitro. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lam WH, Sze KH, Ke Y, et al. Talaromyces marneffei Mp1 protein, a novel virulence factor, carries two arachidonic acid‐binding domains to suppress inflammatory responses in hosts. Infect Immun. 2019;87(4):e00679‐18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pruksaphon K, Nosanchuk JD, Ratanabanangkoon K, Youngchim S. Talaromyces marneffei infection: virulence, intracellular lifestyle and host defense mechanisms. J Fungi. 2022;8(2):200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Qiu Y, Liao H, Zhang J, Zhong X, Tan C, Lu D. Differences in clinical characteristics and prognosis of Penicilliosis among HIV‐negative patients with or without underlying disease in Southern China: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Qiu Y, Feng X, Zeng W, Zhang H, Zhang J. Immunodeficiency Disease Spectrum in HIV‐Negative Individuals with Talaromycosis. J Clin Immunol. 2021;41(1):221‐223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Browne SK, Burbelo PD, Chetchotisakd P, Suputtamongkol Y, Kiertiburanakul S, Shaw PA. Adult‐onset immunodeficiency in Thailand and Taiwan. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(8):725‐734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li X, Hu W, Wan Q, et al. Non‐HIV talaromycosis: Radiological and clinical analysis. Medicine. 2020;99(10):e19185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Othman J, Brown CM. Talaromyces marneffei and dysplastic neutrophils on blood smear in newly diagnosed HIV. Blood. 2018;131(2):269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ly VT, Thanh NT, Thu NTM, et al. Occult Talaromyces marneffei infection unveiled by the novel Mp1p antigen detection assay. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(11):ofaa502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yoshimura Y, Sakamoto Y, Lee K, Amano Y, Tachikawa N. Penicillium marneffei infection with β‐D‐glucan elevation: a case report and literature review. Intern Med. 2016;55:2503‐2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hien HTA, Thanh TT, Thu NTM, et al. Development and evaluation of a real‐time polymerase chain reaction assay for the rapid detection of Talaromyces marneffei MP1 gene in human plasma. Mycoses. 2016;59(12):773‐780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li X, Zheng Y, Wu F, et al. Evaluation of quantitative real‐time PCR and Platelia galactomannan assays for the diagnosis of disseminated Talaromyces marneffei infection. Med Mycol. 2020;58(2):181‐186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen Q, Qiu Y, Zeng W, Wei X, Zhang J. Metagenomic next‐generation sequencing for the early diagnosis of talaromycosis in HIV‐uninfected patients: five cases report. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tsang CC, Teng JLL, Lau SKP, Woo PCY. Rapid genomic diagnosis of fungal infections in the age of next‐generation sequencing. J Fungi. 2021;7(8):636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhu YM, Ai JW, Xu B, et al. Rapid and precise diagnosis of disseminated T.marneffei infection assisted by high‐throughput sequencing of multifarious specimens in a HIV‐negative patient: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang J, Zhang D, Du J, et al. Rapid diagnosis of Talaromyces marneffei infection assisted by metagenomic next‐generation sequencing in a HIV‐negative patient. IDCases. 2021;23:e01055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang W, Ye J, Qiu C, et al. Rapid and precise diagnosis of T. marneffei pulmonary infection in a HIV‐negative patient with autosomal‐dominant STAT3 mutation: a case report. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2020;14:1753466620929225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Qiu Y, Zhang JQ, Pan ML, Zeng W, Tang SD, Tan CM. Determinants of prognosis in Talaromyces marneffei infections with respiratory system lesions. Chin Med J (Engl). 2019;132(16):1909‐1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Le T, Wolbers M, Chi NH, et al. Epidemiology, seasonality, and predictors of outcome of AIDS‐associated Penicillium marneffei infection in Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(7):945‐952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.