Abstract

Adenoid tissue is considered as first line immunological defence mechanism in childhood. Adenoid hypertrophy in children is a common cause of nasal obstruction. It usually gets atrophied by puberty. Adenoid hypertrophy persisting in adults is a cause of nasal obstruction. A randomized prospective study was conducted on adult patients aged above 20 years of age presenting with bilateral nasal obstruction at a tertiary care hospital, for duration of 20 months from January 2018 to August 2019.The differential diagnosis of adenoid hypertrophy was evaluated and role of endoscopic adenoidectomy was studied. The various associated causes of adenoid hypertrophy in adults showed previous history of adeno-tonsillectomy, allergy, deviated nasal septum and smoking. In all cases endoscopic assisted adenoidectomy was performed. Post adenoidectomy patients were asymptomatic in 21 cases, partial improvement in 6 cases and failure in 3 cases. Enlarged adenoid in adults should be considered in the differential diagnosis of cases suffering from bilateral nasal obstruction, or presenting as a nasopharyngeal mass with aural problems. Endoscopic adenoidectomy is safe and reliable. The nasal endoscope aids in removal of adenoid completely with good haemostasis, without any injury to Eustachian tube.

Keywords: Adenoid hypertrophy, Endoscopic adenoidectomy, Adults, Nasal endoscopy

Introduction

Santorini described the nasopharyngeal lymphoid aggregates or Luschka’s tonsil in 1724. Wilhelm Meyer coined the term adenoid in 1870. Adenoid tissue is one of the first line immunological defence mechanisms of the upper aero-digestive tract and reaches its maximal size between 3 to 7 years of age. Adenoids start to atrophy by the age of 10 years & the process is completed by the age of 20 years [1−4]. Although adenoid hypertrophy is considered as a childhood condition to our knowledge there is no study which accurately determines incidence of adenoid hypertrophy in adults. In the current era of nasal endoscopy used as part of routine clinical nasal examination, adenoid tissue is increasingly found in adults. However it is not clearly possible to distinguish neoplastic adenoidal tissue from benign hypertrophy based on the macroscopic appearance alone. Our study aims to assess the adenoid hypertrophy in adults, in patients with bilateral nasal obstruction with respect to clinical features and investigation findings and to assess the effectiveness of trans-nasal endoscopic adenoidectomy.

Materials and Methods

The prospective study conducted on adult patients aged above 20 years of age presenting with bilateral nasal obstruction along with enlarged adenoids after taking informed written consent. At a tertiary care hospital, for duration of 20 months from January 2018 to August 2019. Out of which 30 cases of enlarged adenoids were found. There were 20 males and 10 females. Inclusion criteria included patients with age group more than 20 years, Adenoid hypertrophy in patient with previous adenotonsillectomy and in patients in whom there is endoscopically and radiologically confirmed evidence of adenoid hypertrophy. Exclusion criteria included patients with age group less than 20 years, benign and malignant lesions of the nasopharynx and those patients who are not willing for endoscopic adenoidectomy.

Routine blood investigations, urine for albumin, sugar and microscopy were undertaken. Radiology included X-ray lateral nasopharynx and Computed tomography scan of nose and paranasal sinus. Patients with aural symptoms also underwent pure tone average and impedance audiometry.

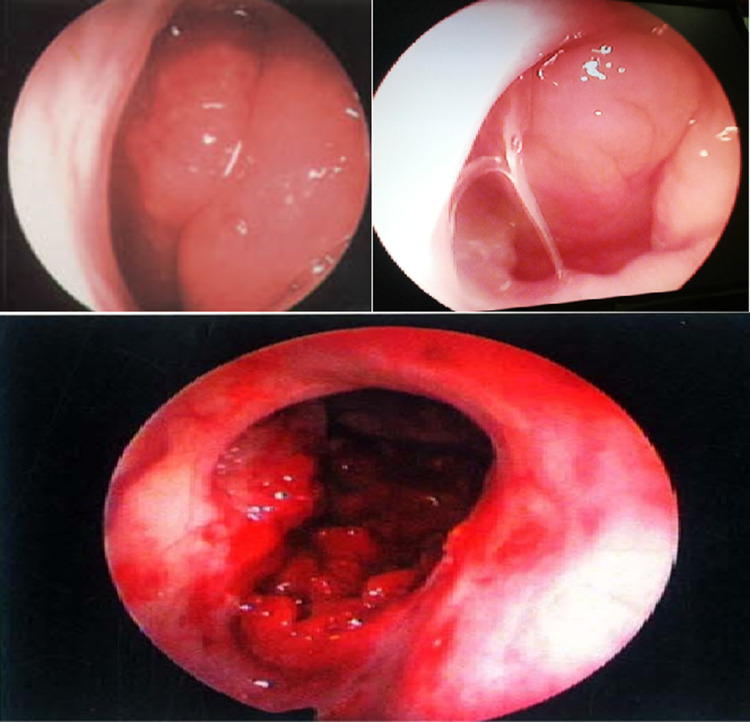

The 0 degree, 4 mm nasal endoscope was utilized to identify the nasopharyngeal mass. Mass either had smooth or an irregular surface. The origin of the masses was from the vault and /or posterior wall of the nasopharynx. Profuse retained secretions were found in front of the adenoid mass at the posterior aspect of the inferior meatus and nasal cavity in 7 cases. Associated chronic sinusitis was found in 7 cases, secretory otitis media in 2 cases and bilateral chronic suppurative otitis media in 1 case.

The patients were operated under general anaesthesia in a supine position with the neck extended. The nasal cavities and nasopharynx were examined with a zero-degree nasal endoscope (4 mm) without any vasoconstrictor packing. If the nasal cavity was congested, ribbon gauze soaked with 4% xylocaine or 0.05% oxymetazoline with adrenaline solution was used to pack nasal cavity for 5 min to shrink the nasal mucosa. A throat pack was also inserted to prevent any blood from entering the trachea. A Boyle-Davis mouth gag was inserted to open the mouth widely as during the classic adenoidectomy. A suitably sized St Claire Thompson adenoid curette with cage was placed transorally into the nasopharynx.

Under nasal endoscopic guidance, the blade of the adenoid curette was placed just above the superior border of the adenoid (Fig. 2b). The nasal endoscope was then taken out from the nose and the adenoid tissue was curetted using sustained force as described in conventional adenoid curettage. Any bleeding was controlled using transoral packing gauze for 3 to 5 min, cauterization was not needed at the adenoid area. Post operatively patients were given oral antibiotics, analgesics and antihistamines. Nasal packing was removed in patients with septoplasty after 48 h. Endoscopic follow up for a period of 6 to 18 months (average of 12 months) was done.

Fig. 2.

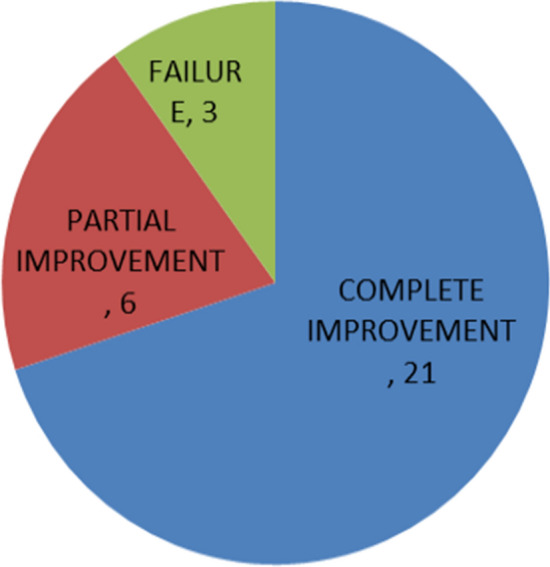

Effectiveness of endoscopic adenoidectomy in adults with adenoid hypertrophy

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics was used for polating results. All symptoms and signs were calculated in percentage. All tables were computed using Microsoft word 2010 and charts using Microsoft Excel 2010.

Results

This study was conducted on adult patients aged above the age of 20 years with bilateral nasal obstruction, 30 such cases of enlarged adenoids were found. There were 20 males and 10 females. The patients studied for a period of 20 months. All patients had bilateral nasal obstruction along with headache in eight cases, nasal tone in four cases and snoring in three cases, postnasal discharge in seven cases, decreased hearing in four cases and rhinorrhoea in four cases. The duration of the symptoms ranged between two and ten years with average of 6 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Symptoms of Adult with Adenoid hypertrophy

| Sr No | Symptoms | No. of subjects | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nasal obstruction | 30 | 100 |

| 2 | Headache | 08 | 26.67 |

| 3 | Postnasal discharge | 07 | 23.33 |

| 4 | Rhinorrhea | 05 | 16.67 |

| 5 | Decreased hearing | 04 | 13.33 |

| 6 | Nasal tone | 04 | 13.33 |

| 7 | Snoring | 03 | 10 |

| 8 | Tinnitus | 04 | 13.33 |

Associated conditions in our series were four patients with history of previous adenotonsillectomy in childhood with one patient having history of septal surgery with partial turbinectomy, five patients with smoking history, two patients with immunocompromised state (HIV), nine patients had nasal allergy. Eleven patients had associated deviated nasal septum, and nine patients had inferior turbinate hypertrophy.

All of the cases reported previous medical treatments in the form of antibiotics, antihistamines and/or decongestants (local or systemic). Most common symptom was nasal obstruction while most common otological sign was retracted tympanic membrane. In all the cases endoscopic assisted adenoidectomy was performed under general anaesthesia. All 30 patients underwent endoscopic adenoidectomy and postoperative period was uneventful. Endoscopic follow for a period of 6 to 18 months was done (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pre op and post op endoscopic view of adenoid hypertrophy

Subjectively, patients became asymptomatic in 21 cases; partial improvement was seen in six cases, whereas three patients showed no improvement at the end of follow-up (Fig. 2).

Endoscopic grading showed patients who were having large adenoids (Grade 3 or 4) as per grading scale (Table 2) and with persistent symptoms of allergic rhinitis were having the recurrences or partial improvement in symptoms.

Table 2.

Endoscopic grading of Adenoid hypertrophy

| Grade | Grade of Adenoid Hypertrophy | Number of subjects |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | No anatomic structure in contact with adenoid | 7 |

| 2 | Adenoid in contact with Torus tubarius | 7 |

| 3 | Adenoid in contact with Vomer | 10 |

| 4 | Adenoid in contact with soft palate at rest | 6 |

Discussion

Obstructive adenoid hypertrophy is usually associated with childhood. Adult form of adenoid hypertrophy is having very few references in literature, possibly due to its under diagnosis as a result of incomplete nasopharyngeal examination, although it has also been overshadowed by accompanying rhino-pharyngeal disorders.

Alaa A-Wahab [1] studied 18 cases (aged 27–59 years) with nasal obstruction and/or serous otitis media in past 3 years (2000 to 2002). All had computerized tomography scan and endoscopic examination and were treated by endoscopic nasopharyngeal mass resection. Histopathology was used to confirm diagnosis by using immunohistochemical staining. All had benign lymphoid hyperplasia on histopathology; using immunohistochemistry it showed predominance of B cell lineage cellular proliferation with IgA and IgG defect, and production of IgM, IgE indicated infection and type I hypersensitivity and surface barrier immunodeficit. Transnasal adenoidectomy provided a complete removal of adenoid without any complications.

Hamdan et al. [2] did a prospective study which was conducted on 55 patients above the age of 17 years who presented with nasal obstruction and 49 patients with no history of nasal obstruction. The overall prevalence of adenoid hypertrophy was 63.6%. The presence of purulent nasal discharge should encourage the treating doctor to do nasal endoscopy for proper diagnosis.

Park SK et al. [3], did a retrospective study on 18 adult patients who had undergone adenoidectomy due to adenoid vegetation. The adenoid to nasopharyngeal ratio in these patients was from 7.5 to 9.0. The main symptom of these patients was snoring; other symptoms were nasal obstruction, postnasal drip, and frequent upper respiratory infection. The prominent pathological findings were squamous metaplasia in surface epithelium and parenchymal fibrosis.

Reda H. Kamel et al. [4] studied on enlarged adenoid and adenoidectomy in 35 adults in Cairo University, Egypt. The nasal endoscopy was utilized to identify the adenoid mass. Adenoidectomy under transnasal endoscopic control was performed and sent for histopathological examination. Surgery resulted in marked improvement in 94% of patients without major complication & 43% had non-specific inflammatory reaction, 6% had follicular hyperplasia, 51% had mixed pattern. Endoscopic follow up in 17 months identified recurrences in 2 cases. It was concluded that enlarged adenoid tissue in adults has some histopathological difference from that in children and transnasal endoscopy was safe and reliable.

Tarek S Jamal [5] in a prospective study of 100 adult patients with nasal obstruction as the main complaint and found that enlarged adenoid were found in 7%. They were visualized with the help of endoscope, shown radiologically and were confirmed by histopathology. Adenoidectomy relieved these patient symptoms successfully without any recurrences.

N Yildrim et al. [6] in a study comparing etiology and pathological features of adult and childhood adenoid hypertrophy found that, both had similar symptoms and associated inflammation. Children had more otitis media with effusion rate. 25% of adults had associated septal deviation. Histopathological features in children were numerous lymph follicles with prominent germinal centers, whereas in adults chronic inflammation with secondary metaplastic changes dominated the picture. This result considers adenoid hypertrophy as a cause or a contributing factor in nasal obstruction in adults and supports the theory that it represents a long standing inflammatory process rather than being a novel benign entity.

Yuce et al. [7] in a study of 12 adults presenting with nasal obstruction due to adenoid vegetation found that 5 had bilateral serous otitis media and 8 had postnasal drip. All patients were subjected to adenoidectomy under general anaesthesia with transnasal endoscopic control. Histopathological examination revealed lymphoid hyperplasia. It was concluded that adenoid hypertrophy may present as the chief cause of nasal obstruction in adults too.

Roy F Nelson [8] did a study on adenoid in adults and found that out of the 19 cases 12 patients were having definitive pathological importance and possible significance was found in 3. In 6 patients tonsillectomy was performed previously without any attention to the adenoids.

James E Mitchell et al. [9] did a retrospective study on 110 adult patients who had biopsies of post nasal tissue. Primary symptoms of patients were Otitis media with effusion in 42%, snoring or nasal obstruction in 43% of cases, cervical lymphadenopathy in 11%, 2 cases of bleeding in post nasal space, 2 were having post nasal drip, 2 cases were incidental and 1 was of facial pain. Biopsies were reported benign in 92 (84%) of patients. Malignant biopsy was found in 18 cases (16%).

Nasal endoscopic examination is a major breakthrough in the diagnosis of sino-nasal disease, it could accurately diagnose the nasopharyngeal adenoid, its size, shape and degree of encroachment on the airway and Eustachian tube [10–13].

In a survey of 15,000 adults (aged > 16 years), the adenoid was resent in 2.5%. Various etiopathogenetic mechanisms have been postulated to explain the presence of lymphoid hyperplasia in the adult nasopharynx, including the persistence of childhood adenoids or re-proliferation regressed adenoidal tissue in response to irritants like smoke, dust or infections. Finkelstein et al. [14] reported the presence of obstructive adenoids in 30% of heavy smokers. Adenoid hypertrophy caused by viruses in adults with compromised immunity, especially those receiving organ transplants and those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), is a well-known phenomenon.

Deviation of nasal septum during its development manifests after adolescence, affecting nasal physiology and predisposing the person to chronic sinonasal inflammation and post-nasal drip [16]. Nasal septal deviation may also indirectly cause low grade chronic inflammation of the adenoids, interfering with their physiological regression. The inhaled air stream, after passing through the narrow nasal cavity is suddenly released and changes direction down wards. As a result, the speed of the air stream becomes slower and the dust, bacilli or poisonous gases adhere or stimulate the nasopharyngeal wall more easily (Horiguti and Yasuo, 1973). A considerable percentage (15%) of the adult patients in the present study gave a history of past adeno-tonsillectomy. This suggests that there was inadequate removal of the adenoidal tissue at the previous surgery [17]. In addition, it is noteworthy that a higher percentage of children with adenoid hypertrophy were reported to suffer from snoring compared with adults in the present study. Snoring is highly prevalent in childhood and is attributable to various causes, among which adenoid hypertrophy is predominant [18]. It is possible that snoring is more frequently reported in children than in adults due to close monitoring by the parents.

In the present study, malignancy was considered in the differential diagnosis. The significant association between adenoid hypertrophy & otitis media with effusion in the childhood group is unsurprising [10]. It is well known that children are more susceptible to middle ear inflammation owing to their shorter and less tortuous Eustachian tubes [20]. The co-existence of obstructive adenoid hypertrophy and obstructive nasal septum deviation in 25% of the adult group is noteworthy.

Although some investigators attributed the enlargement of the nasopharyngeal tonsil in allergic disorders [23]. Enlarged nasopharyngeal tonsils in adults have some differences from that in children. Macroscopically the mass have smooth or irregular surface. The histological features of adenoids in childhood are consistent with hyperplasia marked by increase in volume and abundance of germinal centres [21, 22].

The presence of a lymphoid mass in an adult nasopharynx is suspicious, especially when accompanied by unilateral middle-ear effusion nasopharyngeal cancer should always be ruled out in such cases. Ultra structural changes in lymphocytes in lymphocytes have been demonstrated in smoking induced adenoid hypertrophy and in malignant transformation associated with HIV [15, 17].

Mere presence of adenoid enlargement cannot explain the severity of symptoms. In order to categories adenoid hypertrophy one grading system proposed by Parikh et at. [24] was used, which classify adenoid hypertrophy into grade 1 to 4 on basis of structures in contact with the adenoid tissue. Severity of symptoms and clinical findings were consistent with the grading system.

In our study etiopathogenic mechanisms for adenoid hypertrophy are previous tonsillo-adenoidectomy in 4 cases, allergy in 9 cases, smoking in 5 cases, and with associated deviated nasal septum in 11 cases.

Conclusion

Enlarged adenoid in adults should be considered in the differential diagnosis of cases suffering from bilateral nasal obstruction, or presenting as a nasopharyngeal mass with aural problems. Enlarged adenoid in adults has some macroscopic and microscopic differences from that in children. Histo-pathologically it could be termed as chronic hypertrophic nasopharyngitis or chronic adenoiditis.

Endoscopic adenoidectomy is safe and reliable. The nasal endoscope helps to remove the adenoid completely with good haemostasis, without any injury to Eustachian tube.

Funding

None.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interests.

Ethical Approval

Permission taken from the institutional ethical committee for doing this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alaa A, Wahab H. Endoscopic adenoidectomy in adults. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:271–276. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(03)01275-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamdan AL, Sabra O, Hadi U. Prevalence of adenoid hypertrophy in adults with nasal obstruction. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;37:469–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park SK, Choi ES, Choi JB, Kang MS. The clinical and pathological study of the adenoid vegetation above the age of 20. Korean J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;47:437–443. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamel R, Ishak E. Enlarged adenoid and adenoidectomy in adults: endoscopic approach and histopathological study. J Laryngol Otol. 1990;104(12):965–967. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100114495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jamal TS (1995–1997) Adenoids in adults. JKAU Med Sci 5: 29–34.

- 6.Yildirim N, Şahan M, Karslioğlu Y. Adenoid hypertrophy in adults: clinical and morphological characteristics. J Int Med Res. 2008;36:157–162. doi: 10.1177/147323000803600120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuce I, Somdas M, Ketenci I, Caqli S, Unlu Y. Adenoidal vegetation in adults: an evaluation of 100 cases. Kulak Burun Boqaz Ihtis Derg. 2007;17(3):130–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson RF. Adenoidectomy under local anesthesia. Arch Otolaryngol. 1931;13(6):834–835. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1931.04230040050005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell J, Pai I, Pitkin L, Moore-Gillon V. A case for biopsying all adult adenoidal tissue. Internet J Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;9:2. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fergie N, Bayston R, Pearson JP, Birchall JP. Is otitis media with effusion a biofilm infection? Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2004;29:38–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2004.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho JH, Lee NS, Yoo HR, Such BD. Size assessment of adenoid and nasopharyngeal airway by acoustic rhinomanometry in children. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:899–905. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100145530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chisholm EJ, Lew-Gor S, Hajjoff D. Caulifeild H Adenoid size: a comparison of palpation, nasoendoscopy and mirror examination. Clin Otolaryngol. 2005;30:39–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2004.00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minnigerode B, Blass K. Persistent hypertrophy. HNO. 1974;22:357–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finkelstein Y, Malik Z, Kopolovic J, et al. Characterization of smoking induced nasopharyngeal lymphoid hyperplasia. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:1635–1642. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199712000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.France AJ, Kean DM, Douglas RH, et al. Adenoidal hypertrophy in HIV infected patients. Lancet. 1988;2:1076. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(88)90092-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elahi MM, Frenkiel S, Fagech N. Paraseptal structural changes and chronic sinus disease in relation to the deviated nasal septum. J Otolaryngol. 1997;26:236–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barcin c, Tapan S, Kursakloglu H, , et al. Turkiye de sag likli genceris kinlerde koroner risk faktorlerinin incelenmesi: Kesitel biranaliz. TurkKardiyoloji Dern Ars. 2005;33:96–103. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng DK, Chow PY, Chan CH, et al. An update on childhood snoring. Acta Pediatr. 2006;95:1029–1035. doi: 10.1080/08035250500499432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kieserman SP, Stern J. Malignant transformation of nasopharyngeal lymphoid hyperplasia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;113:474–476. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(95)70088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gates GA, Muntz HR, Gaylis B. Adenoidectomy and otitis media. Ann Otolorhinol Suppl. 1992;155:24–32. doi: 10.1177/00034894921010s106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Passali D, Damaini V, Passali GC, et al. Structural and immunological characteristics of chronically inflamed adenotonsillar tissue in childhood. Clin Diag Lab Immunol. 2004;11:1154–1157. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.6.1154-1157.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright I. Tonsils and adenoids: What do we find? J R Soc Med. 1978;71:112–116. doi: 10.1177/014107687807100206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(2001) Management of Allergic rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 108: S147–S334. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Parikh SR, Coronel M, Lee JJ, Brown SM. Validation of a new grading system for endoscopic examination of adenoid hypertrophy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135:684–687. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]