Abstract

Malignant melanoma of nose and paranasal sinus is a rare and devastating disease. The incidence of intranasal malignant melanomas varies from 0.6 to 3.8%. Extensive local invasion, tumor recurrence, distant metastasis accounts for the poor prognosis with advanced stage having mean survival time of 3.5 years. Here we report 2 cases of malignant melanoma of the left nasal cavity with extensive local invasion to paranasal sinuses and destroying medial orbital wall in both cases along with one eroding cribriform plate and extending intracranially. Both the patient presented with almost similar complaints of unilateral nasal obstruction progressing to bilateral with intermittent episodes of epistaxis and unilateral epiphora. Biopsy from the lesion was proved out to be Malignant melanoma in both the cases. All preliminary radiological investigations including metastatic workup was done. Though there was no evidence of distant metastasis in both the cases, because of extensive local destruction and patient’s preference, both opted for non-surgical management

Keywords: Epistaxis, Malignant melanoma, Paranasal sinus

Introduction

Melanomas arising from the nasal cavity or paranasal sinus is a rare entity [1]. They most commonly involve sun-exposed areas such as head and neck and lower extremities. These tumors arise from melanocytes located in basal layers of skin and mucosal membrane. Majority of these tumors contain melanin pigment with one-third of tumors approximately being weakly pigmented or amelanotic. The incidence of primary head and neck melanomas constitutes 25–30% of all melanomas [2]. Clinically, the most common symptom include progressive nasal obstruction or epistaxis [1]. Mucosal melanomas have poorer prognosis because of local invasion, recurrences, distant metastasis and second primary. Here we report 2 cases of primary malignant melanoma of nasal cavity locally invading paranasal sinuses and eroding medial orbital wall with the second case eroding cribriform plate with intracranial extension but without distant metastasis in a 57-year-old male patient.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 57 year old male patient presented with complaints of left-sided nasal obstruction with intermittent episodes of epistaxis for 6 months. The nasal obstruction was insidious in onset, gradually progressive, with patient complaining of complete nasal block on the left side and intermittent episodes of nasal block on the right side at presentation. It was also associated with intermittent episodes of frank nasal bleed precipitated during exertion. There is also a history of watering from the left eye for the past 2 months. There was no history of difficulty in vision, diplopia, ear, or throat complaints. He was a chronic smoker for the past 20 years but no history of any comorbid illness.

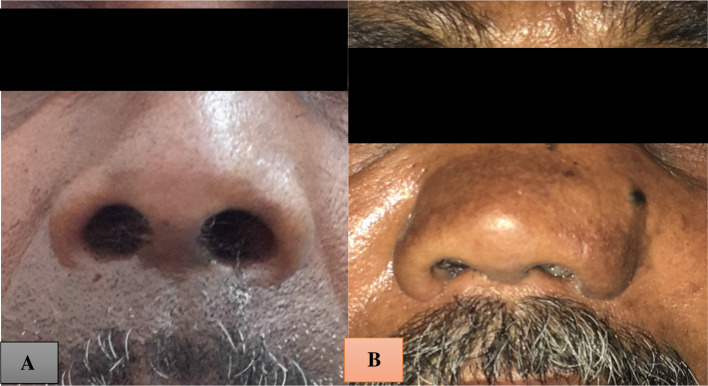

On examination, the vitals and systemic examination were within normal limits. External framework showed fullness of the dorsum of the nose (Fig. 1a). Local examination of the left side nose showed a greyish friable mass completely involving the left nasal cavity extending anteriorly 0.5 cm short of the vestibule (Fig. 2a). Right-sided nasal cavity showed a gross deviation of septum anteriorly.

Fig. 1.

a and b Widening of dorsum of nose with second patient having tumor extending superficially medial to medial canthus of eye

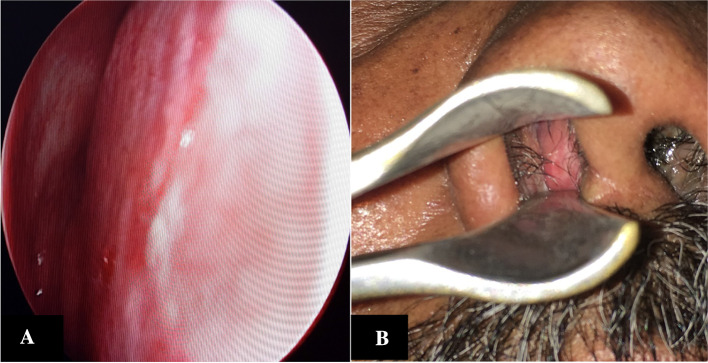

Fig. 2.

a and b Greyish friable mass filling the left nasal cavity and bleeding on touch of the first and second case

On probing the mass was firm in consistency, tender and bleeding on touch. There was no evidence of any regional lymphadenopathy, or any other pigmented lesions elsewhere in the body. In view of epiphora left side, ophthalmological evaluation was done which revealed all extraocular muscle movements and fundus examination to be normal. Examination of oral cavity and oropharynx were also within normal limits.

Preliminary blood investigations were found to be normal. Diagnostic nasal endoscopy revealed a greyish friable mass with irregular surface on left nasal cavity,bleeding on touch involving the whole of the left middle meatus, posteriorly extending up to choana and displacing the septum to the opposite side (Figs. 3, 4). At the same sitting, a biopsy of the lesion was taken and sent for histopathological examination.

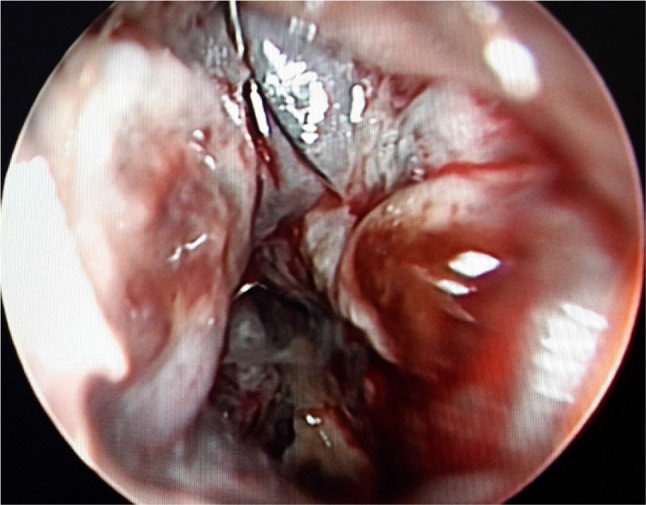

Fig. 3.

DNE: Greyish mass filling whole of left middle meatus and extending till choana posteriorly

Fig. 4.

a and b Septum pushed to right side due to mass effect of left side tumor in both the first and second cases

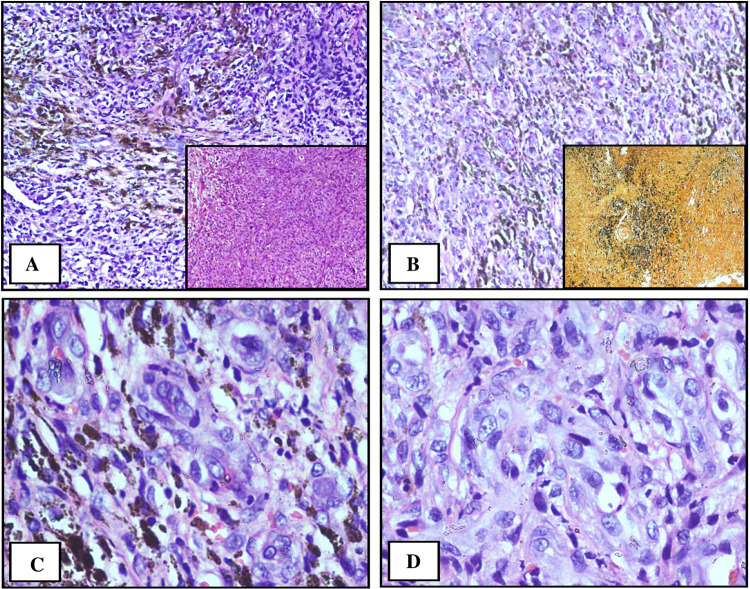

On microscopy, sections revealed oval to spindle appearing tumor cells with vesicular spindly nuclei and prominent nucleoli along with melanin pigment extracellular and in the cytoplasm suggestive of malignant melanoma (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Oval to spindle appearing tumor cells with vesicular spindly nuclei and prominent nucleoli along with melanin pigment extracellular and in the cytoplasm

A contrast-enhanced CT scan of nose and paranasal sinuses was taken and revealed a polypoidal heterogeneously enhancing mass lesion filling entire left nasal cavity pushing the septum to the right side with thinning in inferior aspect and extending into adjacent maxillary infundibulum causing maxillary ostial widening and thinning of the medial wall of the maxillary sinus of the left side. Superiorly, the lesion was found to extend to left ethmoid air cells and left fronto ethmoid recess with bony erosion. Superolaterally, there was destruction of adjacent medial wall of left orbit with mild extension into inferomedial wall and loss of fat planes with medial rectus and posteriorly lesion was extending to choana (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

CT scan showing heterogeneously enhancing mass lesion filling entire left nasal cavity pushing the septum to right side with thinning in inferior aspect and extending into adjacent maxillary infundibulum causing maxillary ostial widening and thinning of the medial wall of the maxillary sinus of left side. Superiorly, lesion was found to extend to left ethmoid air cells and left fronto ethmoid recess with bony erosion. Superolaterally, there was destruction of adjacent medial wall of left orbit with mild extension into inferomedial wall and loss of fat planes with medial rectus and posteriorly lesion was extending to choana

Metastatic workup was done including abdominal echography and whole-body bone scan and was found to be normal. He was planned for Total Maxillectomy with orbital enucleation with intraoperative frozen planned to achieve margins, however, he opted for nonsurgical treatment and was referred to radiation therapy.

Case 2

A 55 year old male, coolie worker by profession, presented to opd with nasal block of left side for 3 years gradually progressing in nature to bilateral nasal obstruction since the past 6 months from presentation. It was also associated with intermittent nasal bleeds and watering form the left eye for the past 6 months. Patient also complained of double vision with associated vision disturbances for 6 months. There was no history of headache, ear, or throat complaints. Much similar to our first patient, there was no history of any medical or comorbid illness, with the patient being a chronic smoker since the past 10 years.

On examination, vitals and systemic examination was within normal limits. External framework showed fullness of dorsum with swelling medial to the medial canthus of the eye (Fig. 1b). Anterior rhinoscopy revealed a greyish friable mass completely obscuring the left nasal cavity extending anteriorly just short of vestibule with a deviation of the septum right side (Figs. 2b, 3b). On probing, the mass was firm, tender and bleeding on touch. Much like our first case there was no other regional lymphadenopathy or pigmentation elsewhere over body. Biopsy was taken during diagnostic nasal endoscopy which was later reported as malignant melanoma.

CECT scan revealed a contrast enhanced mass lesion in the left side of nasal cavity measuring 65 × 28 mm × 43 mm extending anteriorly into left nares, superiorly eroding cribriform plate with minimal intracranial soft tissue component, medially showing displacement and remodeling of the bony septum, laterally showing mass effect over the medial wall of maxillary sinus with fluid retention and mucosal thickening. Superolaterally mass is involving left ethmoid sinuses with rarefaction of bones of sinuses, and superomedially showing erosion and rarefaction of medial wall of left orbit resulting in minimal intraorbital soft tissue component abutting medial rectus posteriorly. Anterosuperiorly, there is erosion of left nasal bone with soft tissue component in the left medial canthus of the eye and posteriorly mass involves left compartment of the sphenoid sinus (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

CT Scan showing a contrast enhanced mass lesion in left side of nasal cavity measuring 65(AP) × 28 mm (tra) × 43 mm (cc) extending anteriorly into left nares, superiorly eroding cribriform plate with minimal intracranial soft tissue component, medially showing displacement and remodeling of bony septum, laterally showing mass effect over medial wall of maxillary sinus with fluid retention and mucosal thickening. Superolaterally mass is involving left ethmoid sinuses with rarefraction of bones of sinuses, and superomedially showing erosion and rarefraction of medial wall of left orbit resulting in minimal intraorbital soft tissue component abutting medial rectus posteriorly. Anterosuperiorly, eroding left nasal bone with soft tissue component in left medial canthus of eye and posteriorly mass involves left compartment of sphenoid sinus

Metastatic workup was done and found to be normal. In view of extensive local invasion of the tumor making surgery difficult and considering poor prognosis, the patient was referred for palliative therapy.

Discussion

Mucosal malignant melanoma is a rare and lethal disease to patients with poor prognosis. The incidence of intranasal malignant melanoma varies from 0.6 to 3.8% [3]. The incidence of melanomas in the upper aerodigestive tract ranges from 0.4 to 4% majority of which involves nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses [4, 5]. In nasal cavity most common area of involvement is nasal septum followed by middle and inferior turbinates [6–8]. Among sinus involvement most common site is maxillary antrum followed by ethmoid air cells. Most common age presentation ranges from 50 to 80 years with males more affected than females, however, age and sex do not affect the prognosis of the disease [9, 10].

The most common symptom include progressive nasal obstruction, epistaxis, or both presenting together. Most of the patients present with advanced stage in addition to its poor prognosis, with a mean survival time of 3.5 years. Because of the extensive local destruction and large size of the tumor in advanced cases, it is often difficult to localize the precise site of tumor origin [11]. The incidence of regional lymph node metastasis varies between 5 and 15% with the submandibular group most commonly involved [12]. Clinically majority of them appear as large, bulky friable masses which bleeds on touch making them indistinguishable from benign polyposis [13]. Local invasion of the tumor into the brain, skull base, carotid artery makes the tumor unresectable contributing to poor prognosis [14].

Diagnostic nasal endoscopic evaluation using flexible or rigid endoscopes along with thorough physical examination of head and neck is required before biopsy of the lesion. Imaging including CT or MRI of the nose and paranasal sinuses is obtained before nasal biopsy to evaluate the extent of primary tumor and presence of nodal metastasis. MRI is better to evaluate tumors extending into skull base or exhibiting neurotropic spread. Also to evaluate distant metastasis additional investigations like chest CT, Bone scan, MRI brain and /or PET scan is useful [15].

Tissue biopsy remains an accurate means of diagnosis. Also certain immunohistochemical markers such as S-100 and HMB-45 can be done to provide completeness of diagnosis.S100 is highly sensitive whereas HMB-45 is highly specific for melanoma. Melanin A is considered highly specific to differentiate melanoma from other malignancies in cases where these markers yield nonspecific results [16]. Yu et al. study yielded a high positive rate on the expression of these 3 markers in primary oral and nasal mucosal melanomas.

Early-stage (stage 1 and 2) lesions of the nasal cavity were proved to give better outcomes (32%) than late stages of 3 and 4 (0%) according to Loree et al. [17]. Owing to rarity of sinonasal tumors their treatment plan remains controversial. Those with localized tumors, the definitive treatment is surgery followed by postoperative radiotherapy. Surgery followed by post-op radiation provides better local control of disease in large bulky tumors and those with incomplete resection. Also prophylactic neck irradiation is recommended for large tumors with or without node. Though surgery and post-op radiation therapy is accepted as the standard goal in patients without distant metastasis, more than 50% of patients may develop distant metastasis later to liver lungs, bones, or brain being the cause of death in most of the patients. The 5 year survival is estimated to be 5–15% because of the aggressive nature of these tumor accounting for its poor prognosis [18].

Though mucosal melanomas were historically considered as radioresistant, recent observations prove them to be useful. Radiotherapy alone is proved to show a 50–75% initial response but long term survival remains an issue [19]. Patients with locally advanced disease or those unwilling for surgery should be considered for radiotherapy as a palliative measure. The role of chemotherapy is considered in those cases with distant metastasis, however the usefulness of concomitant chemoradiation remains controversial.

Conclusion

Malignant melanomas of the nose and paranasal sinus is a rare and lethal disease. The etiology and pathogenesis of these tumors remains unknown. They may remain quiescent for several years making the initial diagnosis several years later. The incidence of regional lymph node metastasis is 10–20% and less than 10% may have distant metastasis. Surgery followed by postoperative radiation therapy is treatment of choice for localized tumors. Local recurrences, distant metastasis may occur even after treatment accounting for its poor prognosis.

Funding

This study was supported by the Manipal University after ethical committee approval.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Huang SF, Liao CT, Kan CR, Chen IH. Primary mucosal melanoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses: 12 years of experience. J Otolaryngol. 2007;36:124–129. doi: 10.2310/7070.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldsmith HS. Melanoma: an overview. CA Cancer J Clin. 1979;29:194–215. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.29.4.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lund V. Malignant melanoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. J Laryngol Otol. 1982;96:347–355. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100092586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKinnon JG, Kokal WA, Neifeld JP, Kay S. Natural history and treatment of mucosal melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 1989;141:222–225. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930410406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stern SJ, Guillamondegui OM. Mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 1991;13:22–27. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880130104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wenig BM (2007) Tumors of the upper respiratory tract, Part A—Nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, and nasopharynx. In: Fletcher CD (ed) Diagnostic histopathology of tumors, vol 1, 3rd edn. Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone, pp 83–149.

- 7.Brandwein MS, Rothstein A, Lawson W, Bodian C, Urken ML. Sinonasal melanoma: A clinicopathologic study of 25 cases and literature meta-analysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:290–296. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1997.01900030064008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jayaraj SM, Hern JD, Mochloulis G, Porter GC. Malignant melanoma arising in the frontal sinuses. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111:376–378. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100137363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Batsakis JG, Suarez P, El-Naggar AK. Mucosal melanomas of the head and neck. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1998;107(626):30. doi: 10.1177/000348949810700715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snow GB, van der Waal I. Mucosal melanomas of the head and neck. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1988;19:549–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson AC, Morgan DA, Bradley PJ. Malignant melanoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Clin Otolaryngol. 1993;18:34–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1993.tb00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Batsakis JG (1999) Pathology of tumors of the nasal cavity and. Paranasal sinuses and neck cancer. WB Saunders Company, Philadelphia, pp 522.39.

- 13.Sil A, Chatrath P, Warwick-Brown N. Malignant melanoma of the nose. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;56:59–62. doi: 10.1007/BF02968779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Popović D, Milisavljević D. Malignant tumors of the maxillary sinus: a ten-year experience. Med Biol. 2004;11:31–34. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goerres GW, Stoeckli SJ, Schulthess GK, et al. FDG PET for mucosal malignant melanoma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:381–385. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200202000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel SG, Prasad ML, Escrig M, Singh B, Shaha AR, Kraus DH, Boyle JO, Huvos AG, Busam K, Shah JP. Primary mucosal malignant melanoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2002;24:247–257. doi: 10.1002/hed.10019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loree TR, Mullins AP, Spellman J, North JH, Jr, Hicks WL., Jr Head and neck mucosal melanoma: a 32-year review. Ear Nose Throat J. 1999;78:372–375. doi: 10.1177/014556139907800511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conley JJ. Melanomas of the mucous membrane of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 1989;12(1248):54. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198912000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harwood AR, Cummings BJ. Radiotherapy for mucosal melanomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1982;8:1121–1126. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(82)90058-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]