Abstract

Fibrous dysplasia, specially of anterior and central skull base region, is a rare disorder. This article discusses about our experience in this pathology. A tertiary care institute based retrospective type study was conducted over a period of 12 years. Demographics, radiology, intraoperative details, pathology and follow up were taken into consideration and the data was analysed. Sixteen patients with complaints of proptosis, diplopia, nasal obstruction and/or facial deformity, underwent endoscopic sinus surgery. Subtotal resection was done in 5 patients. Ethmoid bone involvement was seen in 12 patients. Post operatively, diplopia persisted in one patient and one patient had epistaxis. All patients were followed up for 2–10 years with no other complications reported. Anterior and central skull base involvement is rare in fibrous dysplasia. However, it can be removed effectively by endoscopic approach. Overall safety of patient has more concern rather than complete removal of disease.

Keywords: Fibrous dysplasia, Anterior and central skull base

Introduction

Fibrous dysplasia (FD) is an uncommon developmental bony disorder characterized by replacement of normal bone by fibrous bone. Any bone in the body can be affected however, skull is involved in up to 25% of patients with monostotic FD and almost 50% of patients with polyostotic FD [1].

The third subtype is McCune-Albright syndrome which is usually found in females and characterized by polyostotic FD with precocious puberty (and other endocrine disorders), short stature and pigmentary anomalies [2]. This paper presents our experience over last 12 years and discusses various clinic-pathological aspects of FD.

Material and methods

A retrospective study was conducted in Departments of ENT and Pathology of SMS Medical College, Jaipur, India, a tertiary care institute. Records of patients with craniofacial FD were studied and analyzed. Patient’s age of presentation to our institute, duration of history, complaints, radiology, surgery details, histopathology and follow up were included for analysis. Those with inadequate data were excluded from the study.

Results

A total of 16 patients with anterior skull base FD were included for this study. Average age at presentation was 26.7 years. This comparatively higher average age was skewed, because of one patient who presented at an age of 67 years (age range: 18–67 years). The anatomical location of FD is described in Table 1. Ethmoid bone was the most commonly involved bone.

Table 1.

Location of FD in anterior and central skull base

| Location of FD | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Ethmoid | 12 |

| Frontal | 9 |

| Sphenoid | 7 |

| Maxillary | 4 |

| Orbital | 7 |

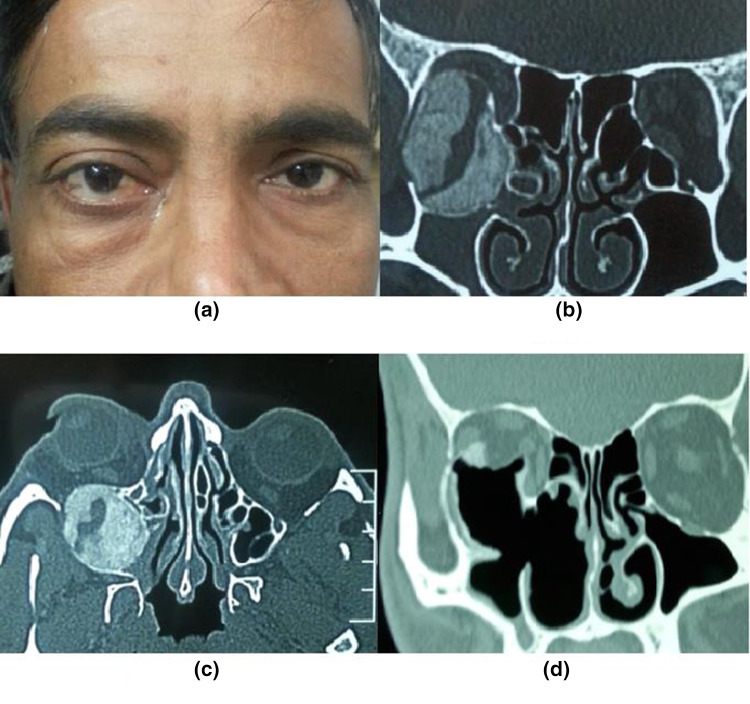

Presenting symptoms included proptosis (14) (Figs. 1 and 2), facial deformity (10) (Fig. 2), diplopia (5) (Fig. 2) and nasal obstruction (4). One of the patients had a secondary frontal mucocele, due to blockage of osteum by the FD involving ethmoids (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

a A male patient of fibrous dysplasia having right eye proptosis. b Coronal view NCCT scan of the same patient showing ground-glass appearance opacity involving right orbit and right maxillary sinus. c The axial cut of NCCT scan showing FD lesion located posterolateral to the right orbit. d post-op NCCT coronal view showing endoscopic excision of the lesion and its adjacent parts

Fig. 2.

a Preoperative photograph of a female patient with Fibrous Dysplasia and right eye proptosis. b, c Demonstrating involvement of the ethmoid region, also involving frontal sinus with secondary mucocele formation lateral to FD lesion as shown in the coronal section. d Post-operative photograph of the same patient with correction of facial deformity. e, f Shows imaging results after endoscopic removal of disease

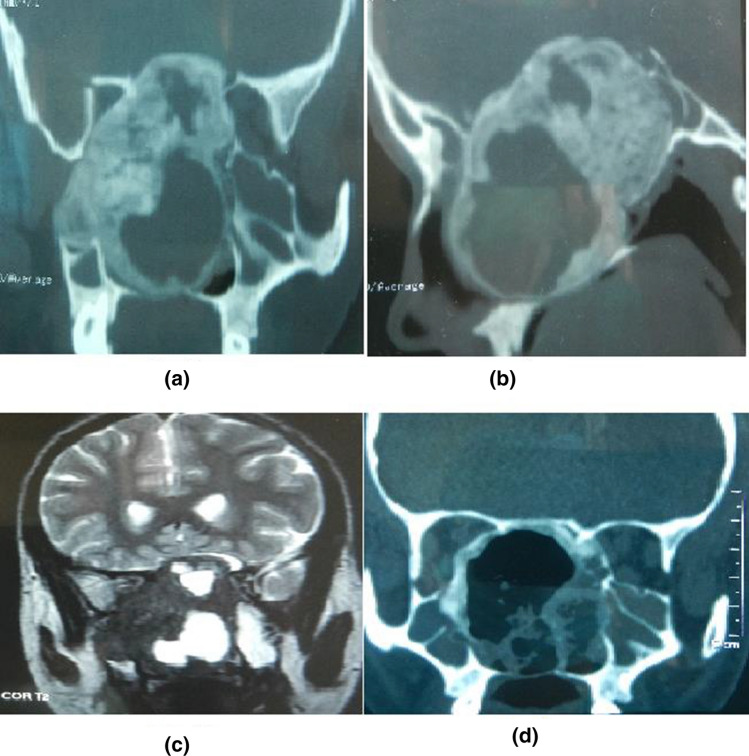

All patients underwent surgery by endoscopic approach. Surgery was done from inside out and diseased bone was removed piecemeal. Kerrison’s punch and Blakesley forceps were used to remove majority of the disease and drill was used near vital areas. It is like opening an eggshell (capsule of the lesion) and removing the contents of the egg from inside. Tissue was sent for histopathology. The aim of the surgery was to remove as much as possible without doing any harm to the patient. A subtotal resection was done in 5 patients, however it was not symptomatic in any (Fig. 3). Apart from one patient in whom diplopia persisted and one who had an episode of epistaxis in postoperative period there were no other major complications. The patients were followed up for any complications and recurrence of the disease.

Fig. 3.

a, b Another case of Fibrous Dysplasia with CT images showing the involvement of sphenoid sinus, intracranial extension along with cystic cavity. c T2 MRI image showing the presence of an extradural FD lesion. d NCCT scan after endoscopic removal of FD with the periphery of the lesion still remaining in-situ

Microscopically, the lesions showed irregularly shaped trabeculae of woven bone with no conspicuous osteoblastic rimming, lying in a fibrous stroma composed of cytologically bland spindle cells. (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Microscopic appearance of Fibrous dysplasia: irregular bony trabeculae without osteoblastic rimming, in a fibrous stroma comprised of spindle cells (H&E stain, 40X)

Discussion

FD is an entity of benign fibro-osseous lesion having characteristic dysplastic changes because of altered osteogenesis leading to the replacement of normal bone and marrow by disorganized fibro-chondro-osseous tissue, resultant of overgrowth of primitive mesenchymal cells [3]. It can occur either within a single bone (monostotic), multiple bones (polyostotic), or in association with McCune Albright syndrome (MAS) [4].

The monostotic form is commonly seen in the 20–30 age group, mildest of the three variants of FD, and as these lesions often remain asymptomatic. Its incidence may be even higher than the quoted figure of 70% thereby often diagnosed incidentally after radiographic evaluation for other reasons. However, the polyostotic form (30%) have an earlier onset in childhood leading to more severe involvement of skeletal and craniofacial region. Histologically monostotic and polyostotic variants share similarities however, these two manifest with different frequencies and severity toward spontaneous fractures, deformities. Therefore, clinically there is no evidence suggesting that the monostotic variant is a precursor of polyostotic [5].

MAS, the most severe form of FD comprise of polyostotic fibro-osseous lesions typical for FD, café –au-lait skin pigmentation along with associated endocrinopathy (e.g. gonadotropin-independent precocious puberty, hyperthyroidism, acromegaly, and Cushing syndrome). The presence of at least two of the three symptoms is sufficient for the diagnosis of MAS [6].

Various theories have been proposed towards the etiology of FD. In 1942, Bony abnormalities due to abnormal mesenchymal differentiation have been proposed by Lichenstein and Jaffe. In 1957, Changus quoted that FD can occur due to osteoblastic hyperplasia. Some other theories given in the 1960s stated the arrest of bone at an immature woven stage and a disturbance of postnatal cancellous bone maintenance [5].

Now attempts have been made to understand its underlying genetics and molecular biology. FD occurs due to mutation in gene GNAS1, which has been implicated for GTPase disturbances leading to prolonged Gs-alpha activation, and increased intracellular cAMP in bone marrow osteoprogenitor cells triggering cellular proliferation with differentiation defects. A possible reason for the fact that not all the bones impaired in polyostotic disease can be attributed to its genetic process i.e. postzygotic, resulting in cellular mosaicism4. Another association of FD seen in Mazabraud syndrome, a rare sporadic disorder of middle age group (mean age 46; range 17–82) and most frequently seen in women (70%), is symbolic of polyostotic FD, multiple soft tissues (intramuscular) myxomas of large muscle groups having increased risk of osseous malignant transformation [7].

To diagnose FD, standard craniofacial NCCT is used which shows characteristic “ground glass” or homogenous appearance and a thin cortex without distinct borders [8]. As the patient’s age advances, CT findings may vary from ground glass to mixed radiodense/radiolucent lesion. If the lesion is around the dentition, then dental radiographs (i.e. panorex and dental films) or a cone-beam CT are to be done [9].

The gross appearance of the FD lesion has been described as a bony expansion with thinned out cortex and the marrow is replaced by nonencapsulated, rubbery, compressible, grayish-white tissue with scattered hemorrhagic flecks giving a gritty texture to the tissue. Its histologic feature is the overgrowth of fibrous tissue within the cancellous bone with stroma having abundant spindle cells in a loose, whorled arrangement, or it may be relatively acellular thus resulting in the poorly formed membranous bone which is irregularly dispersed within the fibrous tissue [10].

The classical histological picture of fibrous dysplasia comprises of irregularly shaped trabeculae of immature woven bone, scattered in a loosely arranged hypercellular fibrous stroma. The trabeculae, are not rimmed by osteoblasts and often attain curvilinear shapes to appear like chinese letters [11].

FD is a slow-growing lesion resulting in facial deformity and distortion of adjacent structures. However, in the young age group and pre-pubertal adolescents, it can show rapid growth. Cortical bone expansion may associate with aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC) or mucoceles and rarely transform into malignancy [9]. In FD, the rate of malignant transformation is seen in less than 1% of the cases. Typically, the malignancy is a sarcomatous lesion, most often osteosarcoma but fibrosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and malignant fibro-histiocytoma have also been reported [12].

A study done by Van Tilburg in 1972, on 144 patients with skull base lesions concluded that the frontal bones were most commonly involved, followed by sphenoid, ethmoid, parietal, temporal, and occipital bones. While another study by Lustig et al. [5] proposed that ethmoid bone was the most frequent to be involved in skull base lesions of FD, with sphenoid, frontal, maxilla, temporal, parietal, and occipital bones to be involved after that in the same order. Our experience has been similar to the latter study.

Amongst paranasal sinuses, the sphenoid sinus is maximally affected by FD, followed by the ethmoid and maxillary sinuses as the anterior cranial base is often affected in patients with craniofacial PFD [13].

Management of FD is guided by the patient’s clinical presentation. Asymptomatic incidental cases are to be routinely followed up by serial CT/MRI scans. Medical management by bisphosphonates inhibiting osteoclast-mediated resorption is used for the treatment of patients with osteodystrophies with limited use in FD [14]. Other medications including aromatase inhibitors (testolactone) and tamoxifen citrate are used for the treatment of precocious puberty in MAS [15]. In radiological unclassified lesions, surgery is determined to be the best course of action. However, complete resection of the lesion may not be required if vital structures (cranial nerves/carotid artery) are involved. In that case, subtotal resection with close follow-up is preferred. Radiotherapy is contraindicated in these cases because of the possibility of malignant transformation [5]. Till few years back surgery for craniofacial FD was usually by external approach.

Lei et al. [16], studied neuroimaging of 12 patients with skull fibrous dysplasia and accordingly surgery was done (like cranioplasty and/or reestablishment of the skull base). 9 out of 12 cases had excellent post-operative outcome, 3 had good outcome with no poor case results. They followed up the patients for 1 to 9 years (mean5.8 years) and reported no recurrence of lesion.

However, with advent of better technology, endoscopic surgery is now being taken up as a preferred approach specially when skull base is being involved. Not only is endoscopic approach cosmetically better, but many times the disease may not be so easily approachable via external approach. There have been few articles in literature supporting endoscopic approach even for bigger lesions [17, 18].

Endoscopic approach has specially been used for optic nerve decompression associated with optic neuropathy due to compression by fibrous dysplasia and literature also mentions that only subtotal removal may be possible/required in many patients with skull base FD [19]. In our experience, endoscopic approach was used for all these patients with successful results. Subtotal removal was done in 5 patients out of 16, however the residual disease was not significant and not symptomatic and did not require revision surgery.

Conclusion

Anterior and central skull base FD is an uncommon disease. Its treatment might be challenging. However, with more experience and better technology, majority of them can be handled well endoscopically. It should be remembered that it is a benign disease and the principle of ‘Primum non nocere’ (First, do no harm) should be followed here. Also leaving behind some residual disease should not be worrisome as it is a very slow growing pathology. Overall, endoscopic approach is a safe and effective approach to treat these lesions.

Author contribution

All the authors have contributed equally in all aspects of the research.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not for profit sectors.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mohnish Grover, Email: drmohnish.aiims@gmail.com.

Anjali Gupta, Email: dranjaligupta.ent@gmail.com.

Sunil Samdhani, Email: sunilsamdhani@gmail.com.

Shruti Bhargava, Email: shrutibhargavapath@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Chong VFH, Khoo JBK, Fan Y-F. Fibrous dysplasia involving the base of the skull. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178(3):717–720. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.3.1780717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCune DJ, Bruch H. Osteodystrophia Fibrosa: report of a case in which the condition was combined with precocious puberty, pathologic pigmentation of the skin and hyperthyroidism, with a review of the literature. Am J Dis Child. 1937;54(4):806–848. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1937.01980040110009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riminucci M, Fisher LW, Shenker A, Spiegel AM, Bianco P, Gehron RP. Fibrous dysplasia of bone in the McCune-Albright syndrome: abnormalities in bone formation. Am J Pathol. 1997;151(6):1587–1600. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eversole R, Su L, ElMofty S. Benign fibro-osseous lesions of the craniofacial complex. A review. Head Neck Pathol. 2008;2(3):177–202. doi: 10.1007/s12105-008-0057-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lustig LR, Holliday MJ, McCarthy EF, Nager GT. Fibrous dysplasia involving the skull base and temporal bone. Arch Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2001;127(10):1239–1247. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.10.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khattab DM, Mohamed S, Barakat MS, Shama SA. Role of multidetector computed tomography in assessment of fibro-osseous lesions of the craniofacial complex. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med. 2014;45:723–734. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrnm.2014.04.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faivre L, Nivelon-Chevallier A, Kottler ML, et al. Mazabraud syndrome in two patients: clinical overlap with McCune-Albright syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2001;99(2):132–136. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(2000)9999:999<00::AID-AJMG1135>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y-R, Wong F-H, Hsueh C, Lo L-J. Computed tomography characteristics of non-syndromic craniofacial fibrous dysplasia. Chang Gung Med J. 2002;25(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JS, FitzGibbon EJ, Chen YR, et al. Clinical guidelines for the management of craniofacial fibrous dysplasia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S2–S2. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-7-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambert PR, Brackmann DE. Fibrous dysplasia of the temporal bone: the use of computerized tomography. Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 1984;92(4):461–467. doi: 10.1177/019459988409200416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeyaraj P. Histological diversity, diagnostic challenges, and surgical treatment strategies of fibrous dysplasia of upper and mid-thirds of the craniomaxillofacial complex. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2019;9(2):289–314. doi: 10.4103/ams.ams_219_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sadeghi SM, Hosseini SN. Spontaneous conversion of fibrous dysplasia into osteosarcoma. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22(3):959–961. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31820fe2bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JS, FitzGibbon E, Butman JA, et al. Normal vision despite narrowing of the optic canal in fibrous dysplasia. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(21):1670–1676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devogelaer J-P (2000) Treatment of bone diseases with bisphosphonates, excluding osteoporosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 12(4). https://journals.lww.com/co-rheumatology/Fulltext/2000/07000/Treatment_of_bone_diseases_with_bisphosphonates,.17.aspx [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Eugster EA, Shankar R, Feezle LK, Pescovitz OH. Tamoxifen treatment of progressive precocious puberty in a patient with McCune-Albright syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 1999;12(5):681–686. doi: 10.1515/JPEM.1999.12.5.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lei P, Bai H, Wang Y, Liu Q. Surgical treatment of skull fibrous dysplasia. Surg Neurol. 2009;72(Suppl 1):S17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2008.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shkarubo AN, Lubnin AY, Bukharin EY, et al. Endoscopic transnasal surgery for giant fibrous dysplasia of the skull base, spreading to the right orbital cavity and nasopharynx (a case report and literature review) Zh Vopr Neirokhir Im N N Burdenko. 2017;81(1):81–87. doi: 10.17116/neiro201780781-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.AlMomen AA, Molani FM, AlFaleh MA, AlMohisin AK (2020) Endoscopic endonasal removal of a large fibrous dysplasia of the paranasal sinuses and skull base. J Surg Case Rep 2020(1):rjz404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.DeKlotz TR, Stefko ST, Fernandez-Miranda JC, Gardner PA, Snyderman CH, Wang EW. Endoscopic endonasal optic nerve decompression for fibrous dysplasia. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2017;78(1):24–29. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1584078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]