Abstract

We assessed the frequency of the parotid gland tumor entities and correlated sex and age in different tumor types. Retrospective data were obtained from three major otorhinolaryngology clinics in Karlsruhe and Pforzheim, Germany within a 10-year period. In total, 1020 cases of parotidectomy for benign and malignant lesions were identified. We found 864 (84.7%) and 156 (15.3%) patients with benign and malignant tumors of the parotid gland, respectively. The most common benign parotid tumor was Warthin’s tumor, followed by pleomorphic adenoma. The most common primary malignant tumor types were acinic cell carcinoma and mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Secondary malignant tumors of the parotid gland included lymphoma and metastatic, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. The frequency of Warthin’s tumors was higher than that of pleomorphic adenomas. A large proportion of the malignant parotid tumors represent metastases from squamous cell carcinoma of the skin of the head and neck.

Keywords: Parotid gland, Benign tumors, Malignant tumors, Warthin’s tumor, Salivary gland tumors

Introduction

Salivary gland neoplasms represent a complex and diverse group of neoplasms of the head and neck region. Approximately 60–80% of salivary gland tumors are located in the parotid gland [1, 2]. Parotid gland tumors are considered to be benign in > 80% of cases [1, 2]. The World Health Organization classification system (2005; modified in 2017) describes 19 and 21 types of benign and malignant salivary gland tumors, respectively, indicating their histomorphological complexity [3]. Epidemiological studies are useful for clinicians to facilitate decision-making for treating patients with salivary gland tumors. Detailed knowledge of epidemiology (e.g., incidence of disease, age and sex of patients, and populations at risk) helps direct the diagnostic and therapeutic procedure. For example, the knowledge of the probable histology of a parotid gland tumor, based on epidemiological characteristics, may lead to a different surgical approach or preoperative diagnostic work-up. This study aimed to analyze the distribution of benign and malignant (primary and metastatic) parotid gland tumors in three institutions over a 10-year period. Secondary goals were to evaluate the influence of patient characteristics (age, sex) on the different histological entities.

Methods

Setting and Patients

Retrospective data analysis was conducted using the data obtained from three otorhinolaryngology clinics in Karlsruhe and Pforzheim, Germany. The available records of patients who underwent parotidectomy at three otorhinolaryngology clinics within a 10-year period (2009–2019) were assessed, and the following parameters were evaluated: sex, age, surgical site, and histological diagnosis of the parotidectomy specimens. The tumors were classified according to the histological categorization of salivary gland tumors established by the World Health Organization. Bilateral cases were included one by one. Data of patients who underwent revision surgery were included in the study only once.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software, version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). For the analysis of potential differences between independent groups, we performed an unpaired t test for quantitative variables. Correlations were calculated using Pearson’s correlation test. A p-value of < 0.05 denoted statistical significance. Quantitative variable data are presented as means ± standard deviations, whereas qualitative labels are presented as absolute numbers and percentages.

Results and Analysis

Overall, 1020 cases of parotidectomy for benign and malignant lesions were identified within the 10-year investigation period. The overall mean age of the patients with parotid gland tumors was 60 ± 15 (range: 1–94) years, with a slight male predominance (565 males vs. 455 females). The tumors were equally distributed between both sides (520 and 500 cases on the left and right side, respectively).

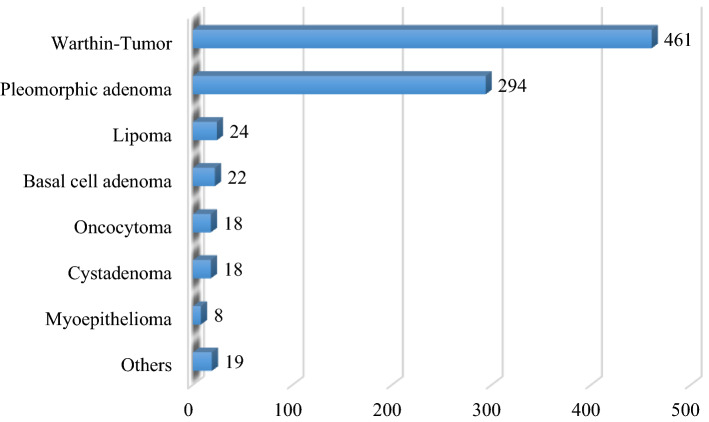

Subsequently, we grouped the cases into benign and malignant lesions and performed additional statistical analysis. Patients’ age and sex distribution for benign and malignant tumors are presented in Tables 1 and 2 and Figs. 1 and 2. We found 864 patients with benign (84.7%) and 156 (15.3%) with malignant tumors of the parotid gland. The mean age of the patients with benign parotid tumors was 58.5 ± 14.5 years. Males were more commonly affected (N = 494) than females (N = 370). However, the Pearson’s Chi squared test did not identify a significant statistical difference between the two groups (p = 0.28). Both sides were equally affected. Overall, the most common benign parotid tumor was Warthin’s tumor (N = 461, 53.4%), followed by pleomorphic adenoma (N = 294, 34%), lipoma (N = 24, 2.8%), and basal cell adenoma (N = 22, 2.5%) (Table 3, Fig. 3). After classifying the patients into their respective sex groups, the most common benign parotid tumor among males was Warthin’s tumor (62.1%), followed by pleomorphic adenoma (26.1%). In the female group, pleomorphic adenoma and Warthin’s tumor were almost equally distributed (44.62 vs. 41.6%, respectively). Concentrating only on the patients with pleomorphic adenoma and Warthin’s tumor, we performed a cross-tabulation and observed that Warthin’s tumor was statistically significantly more common among males than females (Pearson’s Chi squared test, p = 0.000).

Table 1.

Mean age distribution among benign and malignant tumors

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | 864 | 1 | 92 | 58.50 | 14,449 |

| Malignant | 156 | 13 | 94 | 69.03 | 15,790 |

Table 2.

Sex distribution among benign and malignant tumors

| Sex | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||

| Benign tumors | 494 | 370 | 864 |

| Malignant tumors | 71 | 85 | 156 |

| Total | 565 | 455 | 1020 |

Fig. 1.

Age distribution of benign parotid gland tumors

Fig. 2.

Age distribution of malignant parotid gland tumors

Table 3.

Benign tumors of the parotid gland in our study

| Histologic type | Frequency | Percent % |

|---|---|---|

| Warthin’s tumor | 461 | 53.4 |

| Pleomorphic adenoma | 294 | 34.0 |

| Lipoma | 24 | 2.8 |

| Basal cell adenoma | 22 | 2.5 |

| Cystadenoma | 18 | 2.1 |

| Oncocytoma | 18 | 2.1 |

| Myoepithelioma | 8 | 0.9 |

| Canalicular Adenoma | 5 | 0.6 |

| Salivary duct cyst | 5 | 0.6 |

| Lymphoepithelial cyst | 3 | 0.3 |

| Arteriovenous malformation | 1 | 0.1 |

| Cystic lymphangioma | 1 | 0.1 |

| Lymphadenoma | 1 | 0.1 |

| Oncocytic lipoadenoma | 1 | 0.1 |

| Retention cyst | 1 | 0.1 |

| Schwannoma | 1 | 0.1 |

| Total | 864 | 100.0 |

Fig. 3.

Benign tumors of the parotid gland

Concerning primary malignant tumors (N = 77), the most common types were acinic cell carcinoma (N = 15, 19.5%), mucoepidermoid carcinoma (N = 14, 18.2%), adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified (N = 11, 14.3%), and primary squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (N = 9, 11.7%) (Table 4). Females were more commonly affected (42 females vs. 35 males). The secondary malignant tumors of the parotid gland (N = 79) mainly included lymphoma (N = 37, 46.8%) and metastatic, cutaneous SCC (N = 35, 44.3%) (Table 5). The Pearson’s Chi squared test showed that malignant tumors (primary and secondary) were more common in female patients (p = 0.009).

Table 4.

Primary malignant tumors of the parotid gland in our study

| Histologic type | Frequency | Percent % |

|---|---|---|

| Acinic cell carcinoma | 15 | 19.5 |

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma | 14 | 18.2 |

| Adenocarcinoma (NOS) | 11 | 14.3 |

| Primary squamous cell carcinoma | 9 | 11.7 |

| Salivary duct carcinoma | 8 | 10.4 |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 6 | 7.8 |

| Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma | 4 | 5.2 |

| Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma | 3 | 3.9 |

| Undifferentiated Carcinoma | 2 | 2.6 |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 1 | 1.3 |

| Lymphoepithelial carcinoma | 1 | 1.3 |

| Oncocytic carcinoma | 1 | 1.3 |

| Sialoblastoma | 1 | 1.3 |

| Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma | 1 | 1.3 |

| Total | 77 | 100.0 |

Table 5.

Metastatic malignant tumors of the parotid gland in our study

| Frequency | Percent % | |

|---|---|---|

| Lymphoma | 37 | 46.8 |

| Metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma | 35 | 44.3 |

| Metastatic Melanoma | 4 | 5.1 |

| Metastatic squamous cell cancer with unknown primary origin | 3 | 3.8 |

| Total | 79 | 100.0 |

Discussion

This study aimed to analyze the epidemiological data of patients who underwent surgery for a parotid gland tumor. Benign tumors of the parotid gland were found in approximately 85% of the procedures performed, which is consistent with other published data (range: 75–85%) [4, 5]. According to the current literature concerning parotid lesions, pleomorphic adenoma is the most common type of benign tumor [4, 6], accounting for approximately 70% of all salivary gland neoplasms, 80% of all parotid gland tumors, and 53.3–68.6% of benign parotid tumors [4, 6]. The mean age at presentation is 46 years; however, cases have been reported for all ages [2]. Notably, there is a slight female predominance [2]. These data are in accordance with our data. Malignant transformation can occur in 3–15% of cases [4]. Despite its benign nature, cases of metastatic pleomorphic adenoma with distant spread to regular lymph nodes, lungs, or bones have been reported, usually after local recurrence [4]. Warthin’s tumor is the second most common benign neoplasm, accounting for approximately 25% of all parotid lesions and 25–32% of benign parotid tumors [2, 4]. They almost exclusively occur in the parotid gland and periparotid lymph nodes (98.3%). They show a male predominance relative to other benign tumors, with a male–female ratio of 1.6–10:1. These tumors can occur bilaterally (synchronously or metachronously) in approximately 4–10% of cases [2, 4]. Warthin’s tumors appear in an older population (mean age: 59.5 years) [2, 4]. In our study, bilateral Warthin’s tumor incidence was 2.4% (N = 11), with all cases occurring metachronously. Nevertheless, a possible bias should be noted because patients may have decided to be treated in another clinic due to several reasons. We observed a clear predominance of Warthin’s tumor over pleomorphic adenoma (461 vs. 294 cases). From our data and recent publications, there might be a shift in Warthin’s tumor incidence. Generally, a significant change in the incidence ratio of pleomorphic adenoma/Warthin’s tumor has been encountered in the previous 10 years. Similar evidence was shown in a study conducted by Mantsopoulos et al. involving a series of 1624 benign parotid tumors [7]. Another retrospective study conducted in Germany included 165 patients with Warthin’s tumor of 806 patients with parotid tumors over 42 years and showed that Warthin’s tumor was the most frequent type of tumor after 1996, accounting for 42% of all benign lesions. Pleomorphic adenoma accounted for 35% of benign tumors [8]. Analysis of the underlying risk factors of these tumors may explain this shift. To our knowledge, there are no established risk factors for pleomorphic adenoma. However, epidemiological studies have demonstrated a strong association between cigarette smoking and Warthin’s tumor, with smokers being at an eightfold higher risk of developing the tumor than non-smokers [2]. In a study of 149 patients with Warthin’s tumors, approximately 90% were smokers [9]. However, smoking in Germany has decreased following the implementation of anti-smoking campaigns. The proportion of current smokers in the adult population has markedly decreased since 2002–2003 [10]. Particularly in southwestern Germany, tobacco use has substantially decreased in the last 15 years. Τhe proportion of smokers has decreased among men from 31% in 2003 to 25.1% in 2017 and among women from 20.4% in 2003 to 17.4% in 2017 [10]. The decreasing number of smokers observed in the previous decade might result in a reduced incidence of Warthin’s tumors in the next 20 years. Another retrospective study conducted in Austria evaluated 197 cases with Warthin’s tumor and assessed the body mass index and comorbidities related to metabolic disease. The results showed that patients with Warthin’s tumors had a significantly higher body mass index than those with other benign parotid tumors [11]. The percentage of severe obesity cases has increased in recent years [12]. This may explain the increase in Warthin’s tumor in our patients. However, further studies are needed to confirm this association.

Another interesting finding of our study is that the third most common benign parotid tumor was lipoma, which is of mesenchymal origin. Lipomas of the parotid gland are relatively rare, comprising only 0.6–4.4% of the reported benign parotid neoplasms [13]. As the preoperative clinical presentation mimics that of Warthin’s tumor or pleomorphic adenoma, one should consider lipoma in the differential diagnosis of a parotid mass. The parotid gland is generally the most common salivary gland in which lipomas develop (95%) [6]. However, lipomas are rare, although the literature has many case reports [13–15]. Our study showed a higher incidence in male patients (21 males vs. three females) and a mean age of 60 years (59.8 ± 15.3 years). The right parotid gland is more likely to be affected (2:1). These findings are consistent with the current literature [14].

Basal cell adenomas are rare benign tumors, accounting for approximately 2.4–7.1% of benign parotid tumors and more commonly occurring in females [4]. In our study, basal cell adenoma comprised 2.5% of benign parotid tumors (i.e., 22 patients), with a mean age of 68 ± 10 years and a female predominance (13 females vs. 9 males). Oncocytomas account for approximately 1% of all salivary gland tumors and 0.6–1.1% of benign parotid tumors [2]. A possible connection with head and neck irradiation has been suggested [2, 4]. Our study results (18 cases, 2.1% of benign parotid tumors, no sex predilection, mean age: 70 ± 14 years) are consistent with those reported in previous studies [2, 16]. Bilateral lesions were not reported in our study, although the incidence of bilateral oncocytomas in the literature is approximately 7% [2]. We observed the same frequency of 2.1% (18 cases) for cystadenoma. Cystadenomas mostly occur in the minor salivary glands and rarely in the parotid gland. They are rare benign neoplasms, in which the epithelial proliferation is characterized by the formation of multiple cystic structures [4]. They represent 3.1% of major salivary gland benign tumors, with almost 58% occurring in the parotid gland. Literature describes a female preponderance and an age at presentation of approximately 57 years [2, 17]. A mean age of 66 ± 9 years and no sex predilection was observed in our study.

According to our results, for benign parotid tumors, the most common parotid tumor among males is Warthin’s tumor, followed by pleomorphic adenoma. Among females, Warthin’s tumor and pleomorphic adenoma are expected with almost identical incidence.

Regarding malignant parotid tumors, our study showed that acinic cell carcinoma is the most common primary malignant parotid tumor, accounting for approximately 19.5% of all primary malignant parotid tumors (15 cases). Females are more likely to be affected (N = 10 cases, 66.6% females vs. N = 5 cases, 33.3% males). The mean age of occurrence was 54 ± 16 years. Our data are consistent with the current, international literature [2, 18]. We had almost the same number of cases with mucoepidermoid carcinoma (N = 14 cases), like that reported in previous studies. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma is the most common primary salivary gland malignancy in both adults and children, accounting for 4–9% of the major salivary gland tumors. More than 90% of mucoepidermoid carcinoma cases occur in the parotid gland. It has a wide age distribution, with lower rates in pediatric patients and the elderly [2, 18]. The youngest and oldest patients in our study were aged 23 and 89 years, respectively. The mean age of the patients was approximately 64 years, with a relatively high standard deviation of 18 years. Based on the histopathological features, these tumors can be divided into low-, intermediate-, and high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinomas. Histologically, they comprise mucus-secreting, intermediate, and epidermoid (squamous cells) tumors in varying proportions. Low-grade carcinomas contain more cystic spaces lined with mucous cells, whereas high-grade carcinomas contain more squamous cells [19]. Generally, higher grade is associated with male sex, older age, and higher rates of nodal and distal metastases [19]. In our study, we observed that until the age of 60 years, all patients had low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma, whereas intermediate- and high-grade carcinomas occurred after the age of 71 years. Of the 14 patients with this type of tumor, 8 were males and 6 were females.

Adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS) was the third most common primary, parotid, and malignant tumor in our study. By definition, this type of malignant salivary tumor exhibits ductal differentiation but does not resemble other well-defined salivary gland malignancies. Owing to this imprecise definition, the reported incidence of adenocarcinoma is fairly variable, rendering this type of tumor prevalent in some series and less common in other series. Generally, men and women of any age are considered to be equally affected; Adenocarcinoma NOS is one of the most common tumors occurring in children [2, 18, 19]. We reported an incidence of 14.3% of the primary parotid malignancies (N = 11), and age distribution of 41–88 years (mean: 67 ± 17 years). We did not observe any sex preference.

The fourth most common primary salivary parotid malignancy was SCC. Primary SCC represents < 1% of salivary gland tumors [2]. SCC is the predominant histological type of head and neck tumors, although it is rarely reported in the parotid gland. It usually occurs as an intraparotid or periparotid lymph node metastasis from a skin malignancy of the face or scalp region, or another primary mucosal tumor. Therefore, in the case of SCC in the parotid gland, a careful examination (including imaging procedures) must be conducted to rule out metastatic lesions from another site. In all our nine patients (11.7% of the primary, malignant tumors), the involvement of another primary site was excluded through meticulous endoscopy of the upper aerodigestive tract, an examination of the regional skin, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the head and neck, computed tomography of the thorax and upper abdomen, and in some patients positron emission tomography. Males were more commonly affected (males: N = 8, 88.9% vs. females: N = 1, 11.1%). The mean age of the patients was 78 ± 8.7 years. The relatively older age of these patients was also found in other studies [2]. We cannot explain the high frequency of this tumor in our study. Later in this article, we will discuss the metastatic SCC and question this frequency.

We observed a high incidence of non-primary malignant tumors in the parotid gland. The complex structure of the parotid gland, including the associated lymphatic tissue, renders it susceptible to many tumors. On average, the superficial lobe contains 8–9 lymph nodes, whereas the deep lobe contains 1–3 nodes. Lymph nodes are also present superficial to the parotid fascia, in the preauricular region, postauricular region, and immediately inferior in the area of the external jugular region. Parotid nodes are the primary site of drainage from the scalp, forehead, cheek, eye, and auricle [20]. In our series, we noticed a high frequency of non-primary malignancies in the parotid gland because they represented approximately 50% of all malignant parotid tumors. Patients with non-primary salivary malignant tumors may be divided into three major subgroups: those with proximal skin cancer, those with remote, distant solid tumors, and those with systemic hematological disease [21]. The most common origin of squamous cell metastases in the parotid gland are cutaneous SCCs of the skin of the scalp, face, and neck [22, 23]. Their frequency varies according to geographic location and exposure to the sun. It is difficult to differentiate SCC of the parotid gland as a primary parotid malignancy and metastatic disease from a cutaneous or mucosal SCC at a cellular level. Histopathology, clinical examination, and imaging together assist in the diagnosis of a primary lesion. We believe that the high frequency of primary SCC of the parotid gland in our data does not reflect the real proportion of these tumors. The aforementioned diagnostic procedures have a significant but limited sensitivity in diagnosing small tumors. Another possibility is that they represent carcinomas of unknown primary origin, considering the high lymphatic drainage in the parotid gland. We found a percentage of 22.4% (N = 35) of metastatic SCC in the parotid gland in patients with primary tumors in the periauricular region, cheek, or scalp. Other studies reported that metastatic, cutaneous SCC represents approximately 20% and 15% of malignant parotid tumors in males and females, respectively [24]. The mean age of diagnosis in our study was 76 ± 13 years, and males were more frequently affected (N = 20 males, 57%, N = 15 females, 43%).

Another common tumor that metastasizes to the parotid gland is cutaneous, malignant melanoma, although mucosal melanoma should also be considered as a primary lesion, even if its occurrence is rare [23]. In our case series, we reported four cases with metastatic melanomas in the parotid gland. One patient was 39 years, whereas the other patients were > 70 years. The proportion of primary cutaneous malignant melanoma metastasizing into the parotid gland is higher than that of SCC [23]. Owing to the relatively high incidence of metastatic skin tumors in the parotid gland, we strongly advise clinicians to perform a thorough clinical examination of the regional skin of patients presenting with a parotid mass.

We observed a high proportion of patients with hematological lymphocyte-related diseases. Overall, 37 patients had non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and its subtypes (i.e., marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, follicular lymphoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma). Primary parotid gland lymphoma is a small subset of head and neck NHL. The overall incidence is approximately 0.3% of all tumors, 2–5% of salivary gland neoplasms, and 5% of extranodal lymphomas. In contrast to other extranodal locations of NHL, parotid gland involvement is more likely to be of low grade, and patients are associated with a better prognosis than those with other extranodal NHL [25]. A large study of 2,140 patients with parotid gland lymphoma showed a median age of 69 years and a female to male ratio of 1.3:1 [26]. Our data confirmed this finding. The mean age was 68 ± 13 years, and the female to male ratio was 1.5:1 (22 females vs. 15 males). Although Hodgkin lymphoma accounts for 3.5% of overall parotid gland lymphoma cases, in the present study, we did not have any patients [26]. Previous studies also reported parotid metastases from distal primary tumors, such as the upper aerodigestive tract, lungs, kidneys, and breast [20, 21]. We did not observe such metastatic activity in our series.

Because the analyzed data represent material from three clinics within 50 km, the study data may be geographically biased. A nationwide epidemiological study is warranted to verify the incidence of benign and malignant parotid tumors in Germany.

We found a higher incidence of Warthin’s tumors over pleomorphic adenomas. Furthermore, a large proportion of the malignant parotid tumors represent metastases from SCC of the skin of the head and neck. In these cases, a thorough preoperative clinical examination of the regional skin is highly advisable. The findings of this large study of parotid gland tumors conducted in southwest Germany may help our understanding of the differences in the global distribution of salivary gland tumors that have been previously reported.

Funding

No funding was secured for this study.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethics Approval

All methods applied in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Financial Disclosure

There are no financial relationships that could be broadly relevant to the work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lewis JE, McKinney BC, Weiland LH, Ferreiro JA, Olsen KD. Salivary duct carcinoma. Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review of 26 cases. Cancer. 1996;77:223–230. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960115)77:2<223::AID-CNCR1>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradley PJ, Guntinas-Lichius O. Salivary gland disorders and diseases: diagnosis and management. Stuttart: Georg Thieme Verlag; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seethala RR, Stenman G. Update from the 4th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of head and neck tumours: tumors of the salivary gland. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11:55–67. doi: 10.1007/s12105-017-0795-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhan KY, Khaja SF, Flack AB, Day TA. Benign parotid tumors.parotid tumors. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2016;49:327–342. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thielker J, Grosheva M, Ihrler S, Wittig A, Guntinas-Lichius O (2018) Contemporary management of benign and malignant parotid tumors. Front Surg 5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Reinert S. Benigne Speicheldrüsentumoren. Der MKG-Chirurg. 2015;8:142–150. doi: 10.1007/s12285-015-0017-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mantsopoulos K, Koch M, Klintworth N, Zenk J, Iro H. Evolution and changing trends in surgery for benign parotid tumors. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:122–127. doi: 10.1002/lary.24837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franzen AM, Kaup Franzen C, Guenzel T, Lieder A. Increased incidence of Warthin tumours of the parotid gland: a 42-year evaluation. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275:2593–2598. doi: 10.1007/s00405-018-5092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinkston JA, Cole P. Cigarette smoking and Warthin’s tumor. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:183–187. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mikrozensus - Fragen zur Gesundheit, Statistisches Bundesamt, Zweigstelle Bonn. In: Mikrozensus 2017, Statistisches Landesamt Baden-Württemberg

- 11.Kadletz L, Grasl S, Perisanidis C, Grasl MC, Erovic BM. Rising incidences of Warthin’s tumors may be linked to obesity: a single-institutional experience. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276:1191–1196. doi: 10.1007/s00405-019-05319-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein S, Krupka S, Behrendt S, Pulst A, Bleß HH. Bleß Weißbuch Adipositas. Berlin: MWV Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houle A, Mandel L. Diagnosing the parotid lipoma.parotid Lipoma. Case report. NY State Dent J. 2015;81:48–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Starkman SJ, Olsen SM, Lewis JE, Olsen KD, Sabri A. Lipomatous lesions of the parotid gland: analysis of 70 cases. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:651–656. doi: 10.1002/lary.23723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tong KN, Seltzer S, Castle JT (2019) Lipoma of the parotid gland. Head Neck Pathol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Capone RB, Ha PK, Westra WH, Pilkington TM, Sciubba JJ, Koch WM, Cummings CW. Oncocytic neoplasms of the parotid gland: a 16-year institutional review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;126:657–662. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2002.124437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ananthaneni A, Kashyap B, Prasad VVSR, Srinivas V. Cystadenoma: a perplexing entity with subtle literature. J Dr NTR Univ Health Sci. 2012;1:179. doi: 10.4103/2277-8632.102448. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sood S, McGurk M, Vaz F. Management of salivary gland tumours: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines. J Laryngol Otol. 2016;130:S142–S149. doi: 10.1017/S0022215116000566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis AG, Tong T, Maghami E. Diagnosis and management of malignant salivary gland tumors of the parotid gland. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2016;49:343–380. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badlani J, Gupta R, Smith J, Ashford B, Ch’ng S, Veness M, Clark J. Metastases to the parotid gland: a review of the clinicopathological evolution, molecular mechanisms and management. Surg Oncol. 2018;27:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Israel Y, Rachmiel A, Gourevich K, Nagler R. Non-primary salivary malignancies: a 22-year retrospective study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2019;47:1351–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2019.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ying YL, Johnson JT, Myers EN. Squamous cell carcinoma of the parotid gland. Head Neck. 2006;28:626–632. doi: 10.1002/hed.20360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franzen A, Buchali A, Lieder A. The rising incidence of parotid metastases: our experience from four decades of parotid gland surgery. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2017;37:264–269. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boukheris H, Curtis RE, Land CE, Dores GM. Incidence of carcinoma of the major salivary glands according to the WHO classification, 1992 to 2006: a population-based study in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2009;18:2899–2906. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dispenza F, Cicero G, Mortellaro G, Marchese D, Kulamarva G, Dispenza C. Primary non-Hodgkins lymphoma of the parotid gland. Braz J Orl. 2011;77:639–644. doi: 10.1590/S1808-86942011000500017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feinstein AJ, Ciarleglio MM, Cong X, Otremba MD, Judson BL. Parotid gland lymphoma: prognostic analysis of 2140 patients. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:1199–1203. doi: 10.1002/lary.23901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]