Abstract

To assess the benefit of adjunctive alginate therapy in the treatment of laryngopharyngeal reflux disease (LPRD) in a rural population in south India, by comparing the outcome of alginate plus proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy versus PPI monotherapy. 100 consenting adults of both sexes, with LPRD symptoms for ≥ 1 month, with both Reflux Symptom Index (RSI) > 13 and Reflux Finding Score (RFS) > 7, were included in a randomised prospective analytical clinical study. Patients were randomised into two treatment groups for 8 weeks. Group A received oral pantoprazole (40 mg, twice a day),and Group B received oral pantoprazole (40 mg) and oral alginate (500 mg/10 ml) twice a day each. Treatment outcome was assessed with RSI and RFS at 4 and 8 weeks. On follow-ups, both groups showed significant improvement in RSI. At 4 weeks, significant improvement in RFS was seen in Group B, but not in Group A; both groups showed improvement at 8 weeks. The improvement was significantly better in Group B RSI and RFS on both follow ups. On analysis of each RSI item at 8 weeks, choking sensation showed no significant improvement in Group A. All other items showed significant improvement in both groups, with all items except difficulty swallowing and choking sensation showing significantly better improvement in Group B. Analysis of each RFS item at 8 weeks, showed significant improvement in Group B but not in Group A. The addition of alginate to PPI shows greater definitive improvement in both symptoms and signs of LPRD within a short period of 8 weeks, compared to PPI monotherapy, making it a feasible treatment option with good results in routine practice in a rural set-up. Adjunctive alginate therapy enhances the resolution of clinical features of LPRD and is thus beneficial in its routine treatment in all populations

Keywords: Laryngopharyngeal reflux/drug therapy, Pepsin, Alginates/therapeutic use, Proton pump inhibitors/therapeutic use

Introduction

According to the Montreal Consensus Conference, the manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) have been classified into either oesophageal or extraesophageal syndromes [1]. Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease (LPRD) is the most common extraesophageal manifestation of GERD [2]. The growing prevalence of laryngopharyngeal symptoms in up to 60% of GERD patients establishes the existence of an association between LPRD and GERD [1].

Laryngopharyngeal Reflux (LPR) is the backflow of stomach contents into the throat, causing laryngeal inflammation and symptoms such as chronic irritative cough, excessive throat clearing, globus sensation, sore throat and dysphonia [2].It is a significant etiological factor in the development of benign and malignant neoplastic laryngeal growths. In otorhinolaryngological patients with gastroesophageal related disorders, heartburn and other digestive symptoms are present in 6–43% of cases and therefore differs from classic GERD where this is a cardinal symptom [3].

In daily otolaryngologic practice, the diagnosis of LPRD is based on the recognition of associated reflux symptoms and findings through endoscopic examination of the larynx. The Reflux Symptom Index (RSI) and Reflux Finding Score (RFS),developed by Belafsky et al.have been widely used for the diagnosis of LPRD, as they are simple, inexpensive and noninvasive [2]. Laryngopharyngeal pH testing can be used to define LPR, but is not used universally and lacks a gold standard criteria [4].

The mechanisms of GERD associated LPRD are considered to be the acid stimulation of distal oesophageal vagal afferent nerves mediating throat clearing and coughing responses and consequent physical laryngeal injury, or direct laryngeal contact with erosive gastric refluxate. Compared to oesophageal mucosa, laryngeal/pharyngeal mucosa is less resistant to the effects of gastric acid. Thus, small amounts of acid, insufficient to cause esophageal symptoms, may be sufficient to cause laryngeal symptoms [3, 4].Suppression of gastric reflux should therefore be effective against both of these mechanisms [3].

In the case of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, reflux is only modified by removal of its acid component, rather than prevented completely. Other more damaging gastric reflux components such as pepsins and bile acids, may still be present and active even in the absence of strong acid. Liquid alginate, by producing a mechanical anti-reflux barrier within the fundus of the stomach, thereby reducing reflux of gastric contents into the oesophagus and larynx, has been used in the treatment of symptoms of reflux disease for many years [3].Further trials are needed to focus on whether there is an adjunctive benefit to adding alginate for those already on acid suppression [5].

It has been estimated that 4–10% of the patients referred to an otolaryngology clinic have symptoms and/or signs related to LPRD [2]. Reflux has been described as an underlying etiology in 40–60% of patients with various voice and swallowing disorders [6].The high prevalence of GERD in Southern India (22.2%) is comparable with the range found in Western countries(8.8–27.8%).Significant association between GERD and increasing age and BMI, urban environment, lower educational level and paan masala chewing has been found in south India [7].With this high prevalence,70% of India’s population being rural, the paucity of relevant data in this population and inconclusive population based studies on the benefit of alginate therapy (majority of clinical studies on alginates are European) [5], this study was undertaken in a rural population in South India to assess the benefit of adjunctive alginate therapy, by comparing the outcome of alginate plus PPI therapy versus PPI monotherapy in the treatment of LPR.

Materials and Methods

In accordance with ethical standards, a randomised prospective analytical clinical study was conducted from June 2017 to May 2018 in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, in a rurally located hospital in Karnataka, India. 100 consenting adults(≥ 18 years)of both sexes with LPR symptoms for ≥ 1 month, and with both Reflux Symptom Index(RSI) > 13 (self administered questionnaire)and Reflux Finding Score (RFS) > 7 (70° videolaryngoscopic examination),were included in the study. Patients with allergy to the proposed medication, on other medication, taken antireflux medication in the past 1 month, history of upper aerodigestive tract surgery, premalignant or malignant laryngeal diseases, upper aerodigestive or oesophageal neoplasm, chronic pulmonary or sinonasal infections, acute laryngitis, psychiatric disorders, pregnant/lactating women and/or attrition to follow up, were excluded from the study.

Patients were randomised into 2 groups of 50 each, ie. Group A receiving oral pantoprazole 40 mg twice a day half an hour before meals for 8 weeks and Group B receiving oral pantoprazole 40 mg twice a day half an hour before meals and 10 ml oral alginate (formulation containing sodium alginate 250 mg, sodium bicarbonate 133.5 mg and calcium carbonate 80 mg per 5 ml) twice a day after meals for 8 weeks. All patients received relevant vocal hygiene, dietary and lifestyle advice and were reassessed using RSI and RFS (ie. primary efficacy parameters) at the end of 4 weeks and 8 weeks. The change in RSI and RFS from the pre-treatment to the post-treatment assessment, were assessed both within patients for each treatment group and between treatment groups. Descriptive and inferential statistical analysis was conducted. Results on continuous measurements are presented as Mean ± Standard deviation (SD). Parametric data was analysed using unpaired ‘t’ test and non-parametric data was analysed using Mann–Whitney U test or Chi χ2 analysis. P < 0.05 was considered as significant. Statistical software SPSS 20.0, Stata 10.1 and MedCalc 9.0.1were used for data analysis, and Microsoft word and Excel were used to generate graphs and tables.

Results

42 males and 58 females met the inclusion criteria (male:female ratio = 1:1.4). Mean age was 45.62 ± 5.21 years, ranging from 26 to 73 years, with 65% aged between 40 and 50 years. Subjects suffered from symptoms for a duration ranging from 6 to 32 weeks, with a mean of 10.4 ± 3.73 weeks. Both study groups were age, gender, body mass index, symptom duration, mean pre treatment RSI and RFS matched.

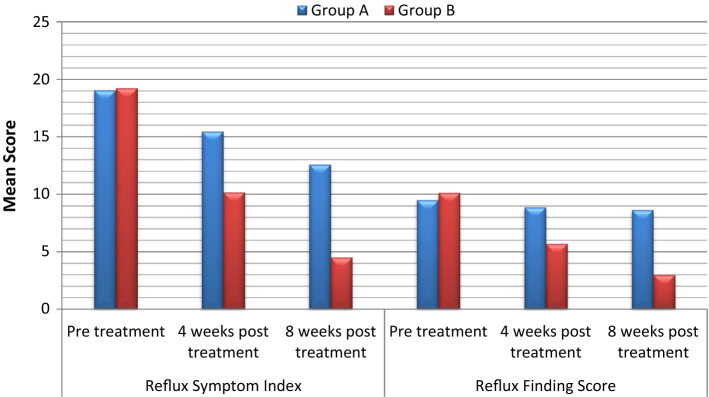

At both 4 and 8 weeks of treatment, both groups showed a significant improvement in total RSI. At 4 weeks, total RFS failed to show significant improvement in Group A, but Group B showed significant improvement; at 8 weeks, significant improvement was observed in both groups. The degree of improvement was significantly better in Group B for both total RSI and RFS, on both follow ups (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of treatment outcome on RSI and RFS at follow up

| Clinical manifestations of LPR | Group A | Group B | Significance of difference between Group A and B mean (P value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Significance of difference between Group A pre and post treatment mean (P value) | Mean ± SD | Significance of difference between Group B pre and post treatment mean (P value) | ||

| Reflux symptom index (RSI) | |||||

| Pre treatment | 19.08 ± 5.16 | – | 19.26 ± 5.37 | – | – |

| 4 weeks post treatment | 15.48 ± 4.92 | 0.0006b | 10.18 ± 4.22 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

| 8 weeks post treatment | 12.60 ± 4.60 | < 0.0001b | 4.52 ± 2.74 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

| Reflux finding score (RFS) | |||||

| Pre treatment | 9.50 ± 2.04 | – | 10.14 ± 2.31 | – | – |

| 4 weeks post treatment | 8.9 ± 1.84 | 0.1257 | 5.72 ± 1.21 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

| 8 weeks post treatment | 8.66 ± 1.72 | 0.0283a | 3.00 ± 1.03 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

aModerately significant (P value:0.01 < P < 0.05)

bStrongly significant (P value: P < 0.01)

Fig. 1.

Comparative analysis of treatment outcome on RSI and RFS

At the end of the study, on analysis of each item constituting the RSI, hoarseness of voice, throat clearing, throat mucus, difficulty swallowing, cough after eating, troublesome cough, lump in the throat and heartburn showed significant improvement in both groups. Choking sensation failed to improve significantly in Group A, but improved significantly in Group B. All items of the RSI except difficulty swallowing and choking sensation showed significantly greater improvement in Group B than in Group A (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of treatment outcome on symptoms of laryngopharyngeal reflux

| Reflux symptom index (RSI) | Group A | Group B | Significance of difference between Group A & B post treatment mean (P value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre treatment mean ± SD | 8 weeks post treatment mean ± SD | Significance of difference between pre and post treatment mean (P value) | Pre treatment mean ± SD | 8 weeks post treatment mean ± SD | Significance of difference between pre and post treatment mean (P value) | ||

| Hoarseness of voice | 0.86 ± 1.14 | 0.32 ± 0.62 | 0.0041b | 0.68 ± 0.77 | 0.06 ± 0.24 | < 0.0001b | 0.0068b |

| Throat clearing | 3.00 ± 0.92 | 1.96 ± 0.86 | < 0.0001b | 2.64 ± 0.96 | 0.74 ± 0.63 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

| Throat mucus | 2.50 ± 1.01 | 1.64 ± 0.94 | < 0.0001b | 2.16 ± 1.25 | 0.36 ± 0.56 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

| Difficulty swallowing | 0.26 ± 0.53 | 0.08 ± 0.27 | 0.0349a | 0.64 ± 1.06 | 0.04 ± 0.19 | 0.0002b | 0.3937 |

| Cough after eating | 2.18 ± 1.04 | 1.36 ± 0.85 | < 0.0001b | 2.06 ± 0.86 | 0.22 ± 0.46 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

| Choking sensation | 0.22 ± 0.46 | 0.09 ± 0.30 | 0.0974 | 0.34 ± 0.55 | 0.02 ± 0.14 | 0.0001b | 0.1381 |

| Troublesome cough | 3.32 ± 1.22 | 2.60 ± 1.11 | 0.0026b | 3.90 ± 1.44 | 1.36 ± 0.72 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

| Lump in the throat | 3.36 ± 1.02 | 2.64 ± 0.94 | 0.0004b | 3.88 ± 0.87 | 1.20 ± 0.57 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

| Heartburn, dyspepsia | 3.18 ± 1.18 | 1.90 ± 0.97 | < 0.0001b | 2.94 ± 0.95 | 0.54 ± 0.54 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

aModerately significant (P value:0.01 < P < 0.05)

b Strongly significant (P value: P < 0.01)

Similar analysis of each item in the RFS showed no significant improvement in all items in Group A. Significant improvement was observed in all items in Group B. Improvement was significantly better in Group B compared to Group A for all items, except thick endolaryngeal mucus (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparative analysis of treatment outcome on laryngoscopic findings of laryngopharyngeal reflux

| Reflux finding score (RFS) | Group A | Group B | Significance of difference between Group A & B post treatment mean (P value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre treatment mean ± SD | 8 weeks post treatment mean ± SD | Significance of difference between pre and post treatment mean (P value) | Pre treatment mean ± SD | 8 weeks post treatment mean ± SD | Significance of difference between pre and post treatment mean (P value) | ||

| Pseudosulcus vocalis | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Ventricular obliteration | 1.08 ± 1.08 | 0.92 ± 1.01 | 0.4460 | 1.04 ± 0.92 | 0.16 ± 0.54 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

| Erythema/hyperemia | 3.28 ± 1.05 | 3.24 ± 1.06 | 0.8500 | 3.04 ± 1.22 | 0.48 ± 0.86 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

| Vocal fold oedema | 0.78 ± 0.93 | 0.54 ± 0.73 | 0.1544 | 0.884 ± 0.71 | 0.16 ± 0.37 | < 0.0001b | 0.0014b |

| Diffuse laryngeal oedema | 1.56 ± 1.07 | 1.34 ± 1.02 | 0.2952 | 1.76 ± 0.71 | 0.54 ± 0.57 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

| Posterior commissure hypertrophy | 2.40 ± 0.63 | 2.26 ± 0.72 | 0.3033 | 2.42 ± 0.61 | 1.48 ± 0.73 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

| Granuloma/granulation | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Thick endolaryngeal mucus | 0.40 ± 0.80 | 0.36 ± 0.77 | 0.7995 | 0.60 ± 0.92 | 0.20 ± 0.61 | 0.0119a | 0.2522 |

aModerately significant (P value:0.01 < P < 0.05)

bStrongly significant (P value: P < 0.01)

Discussion

There are numerous synonyms for LPRD in medical literature: reflux laryngitis, laryngeal reflux, gastropharyngeal reflux, pharyngoesophageal reflux, supraesophageal reflux, extraesophageal reflux, atypical reflux; the most accepted term is extraesophageal reflux [6]. In LPR, oesophageal acid clearance is often normal, with brief ‘flashes’ of reflux reaching the upper oesophageal sphincter and beyond, into the laryngopharynx. These reflux episodes may consist of mainly gas carrying an aerosol of gastric contents, rather than a large volume of liquid bolus. The upper aerodigestive tract, lacking oesophageal acid clearance mechanisms, is more sensitive to the presence of refluxate than the oesophagus. Thus, majority of patients with LPR do not have oesophagitis, the diagnostic sin qua non of GERD. Refluxate contains both hydrochloric acid and enzymes, notably pepsin. Activated pepsin is probably the causative agent for mucosal inflammation in LPR, rather than acid alone. While LPRD and GERD may exist independently, evidence is growing that as severity increases, it is more likely that features of both will be present [6, 8].

Research into early detection and diagnosis of LPR with a simple, economical and non invasive instrument led Belfasky et al. to develop the RSI and RFS, which correlate and are complementary to each other; thus used in our study [2, 6].RSI is a validated, 9-item self-administered questionnaire to assess the severity and response to treatment of upper aerodigestive tract symptoms associated with LPR. Each item is scored between 0 (no problem)and 5 (severe problem), with a maximum total score of 45.An RSI of greater than 13 indicates LPRD [3].The RFS is an 8-item,validated,reliable,easily administered clinical severity scale used to interpret the most common laryngoscopic findings related to LPRD. The scale ranges from 0 (no abnormal findings) to a maximum of 26 (worst score possible).As subtle findings of LPR are present in most individuals, RFS > 7 indicates that the patient has LPRD with 95% certainty [2, 9].

Further tests are reserved for those who do not respond well to treatment, or in whom the diagnosis is unclear. Barium swallow is no longer routinely used to diagnose reflux disease, except if a pharyngeal pouch is suspected. The Bernstein acid perfusion test is mainly of historical interest, but has been used recently in research into reflux-related cough. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is valuable in the diagnosis of GERD, but is often normal in LPR [8]. It is invasive, costly and unnecessary in patients with controllable symptoms [10]. Oesophageal manometry may not be directly helpful in the diagnosis of LPR, but is useful in the assessment of oesophageal dysmotility, which may contribute to symptoms [8]. Twenty-four-hour ambulatory dual-probe pH monitoring is currently the gold standard for the objective diagnosis of LPR, but the presence of abnormal acid reflux on pH monitoring did not predict response to therapy [1, 2].Multichannel intraluminal impedance measurement has been added to pH monitoring (MII-pH) and may improve diagnostic accuracy. Both techniques are invasive, expensive, and are poorly tolerated by some patients [8]. Triple-probe pH monitoring and pepsin immunoassay detection have recently been introduced, but none of these tests are currently appropriate for routine clinical practice [2], and were thus not performed in our rural study.

The treatment options available to patients with LPRD include combinations of dietary and behavior modification, antacids, histamine(H2)-receptor antagonists, PPIs, and fundoplication surgery [9]. As LPRD is one of many extra-oesophageal manifestations of GERD, medical treatment is recommended. The most common class of drugs prescribed for LPR is PPI, which has become the treatment of choice in-spite of conflicting results regarding their response [3, 4, 6]. Empiric antireflux treatment with PPI, according to RSI and RFS is an effective method and an alternate for the 24 h double probe pH monitoring for the diagnosis of LPR [6, 11]. PPIs irreversibly block the final enzyme pathway of acid production, which is why they are the most effective acid suppressant [10]. PPIs act for 12–14 h and need to be taken twice daily to give full 24hours protection given the sensitivity of the upper aerodigestive tract to refluxate. A period of 2–3 months is necessary to establish benefit from the medication [8], and was thus prescribed for 2 months in our study.

Controversies remain about the efficacy of PPI in the treatment of patients with LPR. Certain studies have shown similar effect of PPI and placebo on clinical features in LPR [12, 13]. This placebo effect is however limited to improvements in LPRD symptoms and not clinical findings [3]. Noordzij et al. demonstrated that PPI is ineffective in improving symptoms in patients with LPRD; only hoarseness and throat clearing improved [14]. Bilgen et al. demonstrated an improvement in laryngitis symptoms with PPI [15]. Lam et al. showed that with PPI, there was a significant improvement in symptoms but not laryngeal findings in LPR [16]. In our study, Group A demonstrated a significant decrease in RSI beginning at 4 weeks, but RFS began to show significant improvement at only 8 weeks. The reduction in mean RSI and RFS in our Group A was comparable with a study on the effect of PPIs in LPR by Patigaroo et al. who found obvious improvement symptoms and laryngeal signs in 8 weeks and 16 weeks of therapy respectively [6].

Liquid alginate preparations have been shown to be effective in the treatment of LPRD symptoms, either alone or in combination with PPIs. They have the advantage of being a nonsystemic medication [8]. Alginates do not interfere with PPI absorption. The concept of rebound hyperacidity is an important factor contributing to PPI dependence, which is preventable by weaning PPIs by reducing the dose over 4–6 weeks and using alginates which may prevent ‘rebound relapse’ [10]. PPIs are at best an indirect treatment for LPR, helping to reduce the activation of pepsin; at present there are no drugs which directly oppose the action of pepsin [8]. Alginates have a barrier function by forming a raft in the stomach in combination with gastric acid or gelling agent such as bicarbonate in the formulation, and may also trap pepsin and bile within the raft [10]. Alginates reduce PPI resistant reflux by targeting the acid pocket [17]. Adding an alginate after meals with a late-night dose is helpful if there are breakthrough symptoms on PPIs [10]. In view of these facts, advantages, and the lack of effectiveness of alginates alone [5], both oral alginate and PPI was prescribed in Group B our study.

Tseng et al. observed improvement in RSI and RFS with alginate, but failed to establish it’s superiority over placebo [18]. Leiman et al. found a statistically significant treatment benefit with alginate based therapy [5]. McGlashan et al. inferred that alginate containing Gaviscon is well tolerated in LPR and is effective in improving both symptom scores and clinical findings compared with a control group. It can quickly show symptom improvement that is lacking with even high doses of PPI monotherapy over similar durations [3]. These findings concurred with those in our study in which mean RSI showed a difference of 3.6 and 6.48 in Group A at 4 and 8 weeks respectively, while Group B showed a greater difference of 9.08 and 14.74 over the same duration from the pre-treatment score. Similarly, mean RFS showed a difference of 0.6 and 0.84 in Group A at 4 and 8 weeks respectively, while Group B showed a much greater difference of 4.42 and 7.14 over the same duration from the pre-treatment score These results indicate that alginate reflux suppression can form an effective alternative to management of LPRD patients with PPIs [3]. However, in contrast to our study, McGlashan et al. concluded that RFS improvement under treatment with Gaviscon only achieves statistical significance after 6 months of therapy, indicating that the resolution of clinical findings takes longer than that of patient symptoms [3]. Our study showed statistical improvement in RFS in Group B from 4 weeks itself.

Following successful symptom control, step down to the lowest effective maintenance PPI dose should be tried [10]. Unlike GERD, patients with LPRD require higher doses and longer trial of PPIs to achieve improvement in laryngeal findings [1]. Belfasky et al. noted a lack of association of physical findings with symptoms, indicating that treatment with Gaviscon should continue for at least 6 months, or until complete resolution of clinical findings [19]. In the longer term, most patients can manage their condition by dietary and lifestyle modification, supplemented by a liquid alginate at night. Some patients also find it helpful to have an ‘as required’ PPI [8]. Failure of optimised therapy after 4–8 weeks should suggest secondary-care referral [10]. These were followed in our patients following the end of the study.

The following are the limitations of our study :(1) Oral translation of the validated English RSI questionnaire into the local/regional language, (2) Inter observer variation(between both authors)in laryngoscopic findings and RFS thereof [2], (3) Belfasky’s validated RFS used a flexible endoscope, but a rigid 70° endoscope was used for laryngeal assessment in our study, (4) Presence of findings of laryngeal irritation in over 80% of healthy individuals [1], (5) Lack of actual confirmation of LPRD due to absence of 24hour pH monitoring [2], (6) Non blinded study.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the addition of alginate to PPI shows definitive greater improvement in both symptoms and signs of LPRD within a short period of 8 weeks, compared to PPI monotherapy, thus making it a feasible treatment option with good results in routine practice in rural populations.

Clinical Significance

Adjunctive alginate therapy enhances the resolution of clinical features of LPRD and is thus beneficial in its routine treatment in all populations.

Author contributions

Each author listed in the manuscript has contributed to the study, has seen and approved the submission of this version of the manuscript and takes full responsibility for the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that they have no funding source or financial relationships.

Availability of data and material

Compiled and archived.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in this study on human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the affiliated Institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments and comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

All participants consented to inclusion.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Martinucci I, de Bortoli N, Savarino E, Nacci A, Romeo SO, Bellini M, et al. Optimal treatment of laryngopharyngeal reflux disease. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2013;4(6):287–301. doi: 10.1177/2040622313503485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karakaya NE, Akbulut S, Altıntaş H, Demir MG, Demir N, Berk D. The reflux finding score: reliability and correlation to the reflux symptom index. J Acad Res Med. 2015;5(2):68–74. doi: 10.5152/jarem.2015.698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGlashan JA, Johnstone LM, Sykes J, Strugala V, Dettmar PW. The value of a liquid alginate suspension (Gaviscon Advance) in the management of laryngopharyngeal reflux. Eur Arch Oto Rhino Laryngol. 2009;266(2):243–251. doi: 10.1007/s00405-008-0708-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu C, Wang H, Liu K. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of proton pump inhibitors for the symptoms of laryngopharyngeal reflux. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2016;49(7):e5149. doi: 10.1590/1414-431x20165149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leiman DA, Riff BP, Morgan S, Metz DC, Falk GW, French B, et al. Alginate therapy is effective treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30(2):1–8. doi: 10.1093/dote/dow020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patigaroo SA, Hashmi SF, Hasan SA, Ajmal MR, Mehfooz N. Clinical manifestations and role of proton pump inhibitors in the management of laryngopharyngeal reflux. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;63(2):182. doi: 10.1007/s12070-011-0253-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang HY, Leena KB, Plymoth A, Hergens MP, Yin L, Shenoy KT, Ye W. Prevalence of gastro-esophageal reflux disease and its risk factors in a community-based population in southern India. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12876-016-0452-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watson MG. Review article: laryngopharyngeal reflux-the ear, nose and throat patient. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(1):53–57. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. The validity and reliability of the reflux finding score (RFS) The Laryngoscope. 2001;111(8):1313–1317. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basu KK. Concise guide to management of reflux disease in primary care. Prescriber. 2012;23:19–28. doi: 10.1002/psb.944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naiboglu B, Durmus R, Tek A, Toros SZ, Egeli E. Do the laryngopharyngeal symptoms and signs ameliorate by empiric treatment in patients with suspected laryngopharyngeal reflux? Auris Nasus Larynx. 2011;38(5):622–627. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wo JM, Koopman J, Harrell SP, Parker K, Winstead W, Lentsch E. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with single-dose pantoprazole for laryngopharyngeal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(9):1972. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karkos PD, Wilson JA. Empiric treatment of laryngopharyngeal reflux with proton pump inhibitors:a systematic review. The Laryngoscope. 2006;116(1):144–148. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000191463.67692.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noordzij JP, Khidr A, Evans BA, Desper E, Mittal RK, Reibel JF, Levine PA. Evaluation of omeprazole in the treatment of reflux laryngitis:a prospective, placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind study. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:2147–2151. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200112000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bilgen C, Ogüt F, Kesimli-Dinç H, Kirazli T, Bor S. The comparison of an empiric proton pump inhibitor trial vs 24-hour double-probe pH monitoring in laryngopharyngeal reflux. J Laryngol Otol. 2003;117:386–390. doi: 10.1258/002221503321626438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lam P, Ng M, Cheung T, Wong B, Tan V, Fong D, et al. Rabeprazole is effective in treating laryngopharyngeal reflux in a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(9):770–776. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahrilas PJ, Boeckxstaens G, Smout AJ. Management of the patient with incomplete response to PPI therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;27(3):401–414. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tseng WH, Tseng PH, Wu JF, Hsu YC, Lee TY, Ni YH, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study with alginate suspension for laryngopharyngeal reflux disease. The Laryngoscope. 2018 doi: 10.1002/lary.27111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms improve before changes in physical findings. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:979–981. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200106000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Compiled and archived.