Abstract

We plan to evaluate the various variables associated with the complications of thyroidectomy performed at our department in the last 5 years. Medical records of the patients who underwent thyroidectomy during 2014–2018 were collected. Complications of hypocalcemia and recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy were analysed in terms of the demography, cytopathology and the extent of surgery. Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U-test, Fisher exact test and chi square test were applied to look for any significant associations. P value < 0.05 was considered significant. 123 patients were analysed (87 females, 38 males). Mean age was 38.3 years (range 11–71 years). Most common cytopathology was papillary carcinoma thyroid (Bethesda VI) − 43/123 (35%). 107 of these 123 patients underwent primary surgery, 10 underwent revision surgery while 6 underwent completion thyroidectomy. Seven patients incurred RLN palsy out of which 3 were temporary. RLN palsy was seen in only malignant cases (p < 0.05). Incidence was higher in T4a stage (p < 0.05). However, it had no association with a simultaneous central or lateral neck dissection. Hypocalcemia was seen in 22 patients (17.8%), out of whom 9 patients developed permanent hypocalcemia. It was seen significantly higher in patients undergoing central neck dissection (p < 0.05) and in malignant thyroid lesions (p < 0.05). Gender, age and the cytopathology had no bearing on RLN palsy and hypoparathyroidism. Malignant thyroid lesions had a significantly higher incidence of RLN palsy and hypoparathyroidism. A thorough anatomical knowledge can reduce the incidence of these complications.

Keywords: Thyroidectomy, Recurrent laryngeal nerve, Hypocalcemia, Hypoparathyroidism

Introduction

The incidence of nodular thyroid disease; benign or malignant is quite high. Detailed clinical assessment, fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) and relevant laboratory investigations are the standard ways to reach a diagnosis [1]. Local compressive symptoms and cosmetic reasons are the leading indications for thyroidectomy in a benign lesion. The type of thyroidectomy is based on the cytological and radiological findings. Recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) palsy and hypocalcemia are the leading non-metabolic and metabolic complications of thyroidectomy respectively. The incidence of permanent RLN paralysis is approximately 1–1.5% for total thyroidectomy. Unilateral nerve injury is usually managed conservatively whereas bilateral nerve injury may necessitate urgent airway control measures. Hypocalcemia is the most morbid complication of thyroidectomy affecting quality of life significantly. Risk factors for complications are size of the nodule, higher staging, malignant cytology, revision surgery, simultaneous neck dissection, and surgeon experience etc. [2].

This five-year audit was done to assess the existing practice in the department and to compare our results with literature.

Methods

AIIMS, New Delhi is the tertiary care high burden centre in northern India. Usually the thyroidectomies are performed in patients with malignant cytology and in patients with high risk features for malignancy. Data of patients with thyroid disease was collected retrospectively dated between January 2014 and December 2018 from hospital’s medical record library. The patients who underwent thyroidectomy via standard trans-cervical incision were included in this study. However, the patients who were proven to be having anaplastic carcinoma, or were operated using the robotic system were excluded. Data pertaining to patient profile, cytology, surgery and patient’s hospital course were extracted from patient’s files. Post-operatively 12 months follow-up data was collected.

Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U test, Fisher exact test and chi square test were applied to check statistical association of RLN palsy and hypocalcemia (hypoparathyroidism) with various factors. Hypocalcemia and RLN palsy were further subdivided into temporary and permanent category. Permanent hypoparathyroidism is defined as persistent clinical symptoms of hypocalcemia even after 12 months that require calcium and vitamin D supplementation [3]. Similarly, vocal cord palsy which persisted even after 12 months of follow-up was categorised as permanent RLN palsy.

Results

One hundred thirty eight thyroid surgeries were performed in the department of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck surgery of AIIMS, New Delhi for the mentioned duration. Five patients diagnosed with anaplastic carcinoma were excluded as no definitive surgical intervention was done in view of local spread or distal metastasis. We were not able to retrieve complete data of ten patients. So, 123 patients were included in the study and we present the findings henceforth.

The age ranged from 11–77 years (mean—38.3 years). Out of 123 patients, 87 were females while 38 were males. 121 patients had presented with persistent neck swelling while in two patients thyroid nodule was diagnosed incidentally. 112 patients were euthyroid. Hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism was found in nine patients and in one patient respectively. History of alcoholism or smoking was found in 11 out of 123 patients. The average size of the thyroid nodule on clinical examination was 4.3 cm, with the maximum size being 30 cm of a benign adenomatous goitre.

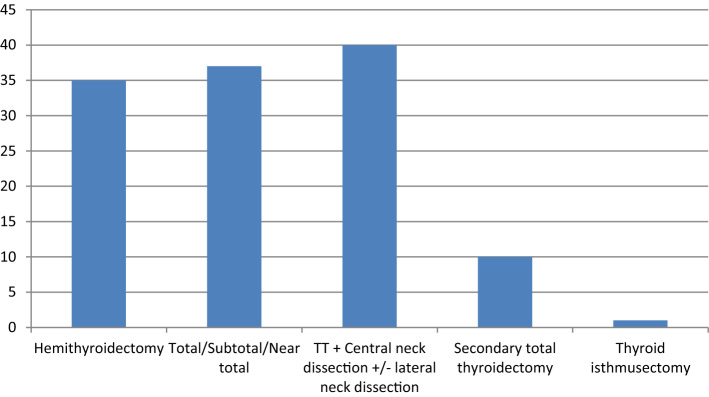

107 patients underwent primary thyroid surgery and 10 patients underwent secondary total thyroidectomy after a previous history of thyroidectomy long back; not related to the current disease. Six remaining patients underwent completion thyroidectomy after undergoing hemithyroidectomy elsewhere for a suspected benign disease which later turned out to be malignant. Out of 117 patients, six patients’ FNAC report could not be traced. Amongst remaining 111 patients, FNAC reported grade VI Bethesda cytology in 43 patients (39%) (Table 1). The distribution of surgeries based on the extent has been tabulated below (Fig. 1). Based on the post-operative histopathology report, 75 patients (including six completion thyroidectomy patients) harboured malignant neoplasm whereas 48 patients had benign nodules.

Table 1.

Cytopathology of the thyroid nodules of the patient population

| Bethesda staging | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Bethesda I | 7 |

| Bethesda II | 8 |

| Bethesda III | 14 |

| Bethesda IV | 25 |

| Bethesda V | 14 |

| Bethesda VI | 43 |

| Report not traced | 6 |

| Completion thyroidectomy | 6 |

| Total patients | 123 |

Figure. 1.

Procedure-wise distribution of thyroidectomies

Table 2 tabulates the surgical complications distribution based on the type of surgery performed. Temporary post-operative hypocalcemia was noticed in 24 patients (19.5%) and permanent hypocalcemia was noticed in nine patients (7.3%). Hypocalcemia was significantly increased when the patients underwent central neck dissection (p < 0.05) or when the post-operative histopathology showed a malignant neoplasm (p < 0.05). No variation was noticed across different age groups, different gender and occurrence of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy. Out of 24 patients, 21 had malignant thyroid swelling out of which 17 belonged to T1 or T2 stage. Hence, higher T-stage was not found to have any impact on the occurrence of hypocalcemia.

Table 2.

Procedure-wise distribution of complications

| Type of surgery | Hypocalcemia (%) | RLN palsy (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Hemithyroidectomy | 0 | 1 (2.8) |

| Sub-total/total thyroidectomy | 10 (27) | 1 (2.7) |

| Total thyroidectomy + Central neck dissection ± lateral neck dissection | 14 (35) | 5 (12.5% |

| Completion thyroidectomy | 0 | 0 |

| Isthmusectomy | 0 | 0 |

Nine patients had preoperatively documented vocal cord palsy. Apart from these nine, seven other patients developed vocal cord palsy in the post-operative period. Temporary and permanent recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy was found in three and two patients respectively, while two patients were lost to follow up. Permanent RLN palsy was documented only in malignant cases (p < 0.05).Two patients of T2, three patients of T3 and three patients of T4a sustained recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy. RLN palsy showed positive association with a higher T stage (T4a), as all the three patients of T4a sustained at least a temporary RLN paresis/palsy.

Sub-group analysis was conducted by dividing the patient population in three groups according to age, that is < 15 years, 15–55 years and > 55 years. We could not find any significant association of a particular age group with either hypoparathyroidism or with recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation of age group with complications. No significant association was seen between a particular age group and any of the surgical complications

| Age group | Hypocalcemia | No hypocalcemia | RLN palsy | No RLN palsy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 15 years | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| 15–55 years | 20 | 84 | 6 | 98 |

| > 55 years | 2 | 13 | 0 | 15 |

Discussion

Detailed anatomical knowledge and emergence of techniques to identify RLN and parathyroid glands have improved surgical results post-thyroidectomy. Our patient profile is in synchrony with the published literature. Across multiple studies, alcohol and cigarette smoke do not appear to increase the risk of thyroid malignancy as seen in our study. Some studies show that alcohol and smoking have an inverse relationship with the risk of thyroid malignancy [4–6].

Temporary and permanent hypoparathyroidism are the most common iatrogenic morbidity following thyroidectomy. It significantly affects quality of life and adds substantial financial burden on family and healthcare system [7, 8]. Hence, it is imperative to analyse the associated factors which increase the risk of hypocalcemia. A meta-analysis showed no association between age and hypocalcemia but incidence of post-operative hypocalcemia was found more in women [9]. We did not find any significant association between age or gender and risk of thyroid malignancy.

Incidence of transient hypocalcemia ranges from 1.6 to 50% while permanent hypocalcemia occurs in 1.5–4% of the patients [7]. In this study, temporary and permanent hypocalcemia was noticed in 24 patients (19.5%) and nine patients (7.3%) respectively. Topographic anatomy of parathyroid, TN staging and surgeon experience are the most important factors influencing parathyroid preservation [10]. Occurrence of hypocalcemia was not documented in any hemithyroidectomy, isthmusectomy and completion thyroidectomy patients in our study. A meta-analysis in this regard evaluating complications in completion thyroidectomy showed that delayed completion thyroidectomy (after 90 days), had a higher rate of vocal cord paresis and hypoparathyroidism than early completion thyroidectomy (7–90 days) [11].

In subgroup analysis, 10 (27%) of the patients undergoing total thyroidectomy (TT) alone; and 14 (30%) of the patients undergoing TT + Central Neck Dissection (CND) suffered from hypocalcemia in the post-operative period. Higher incidence of permanent hypocalcemia can be attributed to the fact that our setup chiefly tends to malignant thyroid neoplasms. We found that the risk of hypocalcemia significantly increases in surgeries of malignant thyroid neoplasms (p < 0.05).

Our data shows significantly increased post-operative hypocalcemia when central neck dissection is performed (p < 0.05). Seo et al. [12], in their analysis of 192,333 patients, show significantly increased incidence of permanent hypocalcemia in patients who underwent TT + CND as compared to patients who underwent TT alone. Ahn et al. [13] evaluated 361 patients, they concluded that performance of CND significantly increased the chances of RLN palsy, post-operative hypocalcemia and prolonged the operative time. Mitra et al. [14] concluded that total thyroidectomy when combined with CND significantly raises the chances of transient and permanent hypoparathyroidism. Giordano et al. [15] in a retrospective study of 1087 patients reported higher rates of transient hypoparathyroidism with ipsilateral or bilateral CND, whereas permanent hypoparathyroidism was significantly higher in bilateral CND. Calò et al. [16] raise questions about the need of CND since it increases the chances of transient hypoparathyroidism in their data but does not significantly decrease the rates of loco-regional recurrence in differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Garcia et al. [17] argue that CND is not a cost-effective procedure to treat low risk papillary carcinoma thyroid (PTC) when compared to TT alone. However, a systematic review in 2012 found no increased incidence of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy or hypoparathyroidism with performance of CND along with TT [18].

In two patients, parathyroids were accidentally removed but were subsequently auto-transplanted. Out of them one patient developed permanent hypoparathyoidism. There are studies that show association of hypocalcemia with topographic anatomy, output of centre, operative time, inter-surgeon variation, re-exploration for complications and auto-transplanted parathyroid [19–22]. We could not find any association with these factors.

The other worrisome complication is recurrent laryngeal nerve injury. Temporary palsy has been found to occur in about 10% while permanent palsy occurs in up to 2.3% of the cases [23]. All patients had their vocal cord status documented during the pre-operative evaluation. Nine patients had vocal cord palsy pre-operatively and showed no improvement in the post-operative period. There were seven patients who developed post-operative recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy. Out of these, three improved, two sustained palsy on 1 year follow up and two patients were lost to follow up. None of these patients had symptoms of aspiration in the immediate and late post-operative period, as well as on 1 year follow up. None of the patients required any surgical intervention on vocal cords. Joliat et al. [24] report data of 451 thyroidectomies, with 63 patients sustaining post-operative vocal cord paresis. Serpell et al. [25] have showed that right RLN is at a significantly higher risk of injury as compared to the left RLN. Their reported incidence of RLN injury was 1.5%. We found no significant difference between the incidences of injury between the two sides.

We found no correlation of RLN injury with previous surgical status, size of the thyroid nodule or simultaneous performance of central neck dissection. However, these seven cases of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy occurred only in malignant cases. Dhillon et al. [26] showed increased risk of RLN injury with larger primary thyroid lesions and CND in their data of 1547 patients. We found that the risk of RLN injury significantly increased when stage T4a tumours were operated (p < 0.05).

Numerous authors have tried different methods to minimise the complication rate in thyroid surgery. The suggested methods like RLN monitoring and frozen section examination for parathyroid are useful. However, it is the thorough knowledge of surgical anatomy, it’s possible variants and meticulous surgical technique that decreases the chances of RLN or parathyroid injury [27, 28].

Our study has some limitations. Our data was heterogenous due to different surgeons involved in the procedure over last 5 years and retrospective nature of the study. Our patient population also suffered from selection bias as our patient population that got operated was primarily afflicted with malignant lesions of thyroid.

Conclusion

Our data shows a significantly higher incidence of RLN palsy and hypoparathyroidism in malignant thyroid lesions as compared to benign lesions, possibly because of a greater extent of surgery and anatomical distortion caused by infiltrative lesions. The RLN palsy was also higher in T4a stage of malignancy further underlying the role of size and anatomical distortion in contributing to complications. Hypoparathyroidism incidence is also higher when central neck dissection was performed due to an insult to vascular supply of parathyroid glands.

These complications can be minimised by the surgeon with his or her thorough anatomical knowledge and careful, meticulous dissection.

Funding

The authors declare no funding source.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

As it was a retrospective observational study, institutional ethical clearance was not obtained.

Consent for Publishing.

As there is no breach in confidentiality all patients consented for publishing their data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Rabia Monga, Email: rabiamonga88@gmail.com.

Anupam Kanodia, Email: kanodiaanupam@gmail.com.

Smile Kajal, Email: smilekajal92@yahoo.com.

David Victor Kumar Irugu, Email: mrkumardav27@yahoo.com.

Kapil Sikka, Email: kapil_sikka@yahoo.com.

Alok Thakar, Email: drathakar@gmail.com.

Rakesh Kumar, Email: winirk@hotmail.com.

Suresh C. Sharma, Email: Suresh6sharma@yahoo.com

Shipra Agarwal, Email: drshipra0902@gmail.com.

Hitesh Verma, Email: drhitesh10@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Unnikrishnan AG, Menon UV. Review Article Thyroid disorders in India : An epidemiological perspective. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2011;15:78–81. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.83329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christou N, Mathonnet M. Complications after total thyroidectomy. J Visc Surg. 2013;150(4):249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stack BC, Bimston DN, Bodenner DL, et al. American association of clinical endocrinologists and american college of endocrinology disease state clinical review: postoperative hypoparathyroidism - definitions and management. Endocr Pract. 2015;21(6):674–685. doi: 10.4158/EP14462.DSC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang H, Zhao N, Chen Y, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of thyroid cancer: a population based case-control study in connecticut. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1032:1–14. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-98788-0_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sawicka-Gutaj N, Gutaj P, Sowinski J, et al. Influence of cigarette smoking on thyroid gland–an update. Endokrynol Pol. 2014;65(1):54–62. doi: 10.5603/EP.2014.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiersinga WM. Smoking and thyroid. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2013;79(2):145–151. doi: 10.1111/cen.12222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grainger J, Ahmed M, Gama R, Liew L, Buch H, Cullen RJ. Post-thyroidectomy hypocalcemia: impact on length of stay. Ear Nose Throat J. 2015;94(7):276–281. doi: 10.1177/014556131509400711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eismontas V, Slepavicius A, Janusonis V, Zeromskas P, Beisa V, Strupas K. Predictors of postoperative hypocalcemia occurring after a total thyroidectomy : results of prospective multicenter study. BMC Surg. 2018;18(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12893-018-0387-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eismontas V, Slepavicius A, Janusonis V, et al. Predictors of postoperative hypocalcemia occurring after a total thyroidectomy: results of prospective multicenter study. BMC Surg. 2018;18(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s12893-018-0387-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abboud B. Topographic anatomy and arterial vascularization of the parathyroid glands practical application. Presse Med. 1996;25(25):1156–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bin Saleem R, Bin Saleem M, Bin SN. Impact of completion thyroidectomy timing on post-operative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gland Surg. 2018;7(5):458–465. doi: 10.21037/gs.2018.09.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seo GH, Chai YJ, Choi HJ, Lee KE. Incidence of permanent hypocalcaemia after total thyroidectomy with or without central neck dissection for thyroid carcinoma: a nationwide claim study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2016;85(3):483–487. doi: 10.1111/cen.13082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahn D, Sohn JH, Park JY. Surgical complications and recurrence after central neck dissection in cN0 papillary thyroid carcinoma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2014;41(1):63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitra I, Nichani JR, Yap B, Homer JJ. Effect of central compartment neck dissection on hypocalcaemia incidence after total thyroidectomy for carcinoma. J Laryngol Otol. 2011;125(5):497–501. doi: 10.1017/S0022215110002471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giordano D, Valcavi R, Thompson GB, et al. Complications of central neck dissection in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma: results of a study on 1087 patients and review of the literature. Thyroid. 2012;22(9):911–917. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calo PG, Conzo G, Raffaelli M, et al. Total thyroidectomy alone versus ipsilateral versus bilateral prophylactic central neck dissection in clinically node-negative differentiated thyroid carcinoma. a retrospective multicenter study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(1):126–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia A, Palmer BJA, Parks NA, Liu TH. Routine prophylactic central neck dissection for low-risk papillary thyroid cancer is not cost-effective. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2014;81(5):754–761. doi: 10.1111/cen.12506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shan C-X, Zhang W, Jiang D-Z, Zheng X-M, Liu S, Qiu M. Routine central neck dissection in differentiated thyroid carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(4):797–804. doi: 10.1002/lary.22162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pattou F, Combemale F, Fabre S, et al. Hypocalcemia following thyroid surgery: incidence and prediction of outcome. World J Surg. 1998;22(7):718–724. doi: 10.1007/s002689900459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arman S, Vijendren A, Mochloulis G. The incidence of post-thyroidectomy hypocalcaemia: a retrospective single-centre audit. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2019;101(4):1–6. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2018.0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orloff LA, Wiseman SM, Bernet VJ, et al. American thyroid association statement on postoperative hypoparathyroidism: diagnosis, prevention, and management in adults. Thyroid. 2018;28(7):830–841. doi: 10.1089/thy.2017.0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chadwick DR. Hypocalcaemia and permanent hypoparathyroidism after total/bilateral thyroidectomy in the BAETS registry. Gland Surg. 2017;6(Suppl 1):S69–S74. doi: 10.21037/gs.2017.09.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeannon J-P, Orabi AA, Bruch GA, Abdalsalam HA, Simo R. Diagnosis of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy after thyroidectomy: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(4):624–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joliat G-R, Guarnero V, Demartines N, Schweizer V, Matter M. Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury after thyroid and parathyroid surgery: incidence and postoperative evolution assessment. Medicine. 2017;96(17):e6674–e6674. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Serpell JW, Lee JC, Yeung MJ, Grodski S, Johnson W, Bailey M. Differential recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy rates after thyroidectomy. Surgery. 2014;156(5):1157–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dhillon VK, Rettig E, Noureldine SI, et al. The incidence of vocal fold motion impairment after primary thyroid and parathyroid surgery for a single high-volume academic surgeon determined by pre- and immediate post-operative fiberoptic laryngoscopy. Int J Surg. 2018;56:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simon D, Boucher M, Schmidt-Wilcke P. Intraoperative avoidance and recognition of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy in thyroid surgery. Chirurg. 2015;86(1):6–12. doi: 10.1007/s00104-014-2816-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Périé S, Aït-Mansour A, Devos M, Sonji G, Baujat B, St Guily JL. Value of recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring in the operative strategy during total thyroidectomy and parathyroidectomy. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2013;130(3):131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]