Abstract

Random fusions of genomic DNA fragments to a partial gene encoding a signal sequence-deficient bacterial alkaline phosphatase were utilized to screen for exported proteins of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in Escherichia coli. Twenty-four PhoA+ clones were isolated and sequenced. Membrane localization signals in the form of signal sequences were deduced from most of these sequences. Several of the deduced amino acid sequences were found to be homologous to known exported or membrane-associated proteins. The complete genes corresponding to two of these sequences were isolated from an A. actinomycetemcomitans lambda phage library. One gene was found to be homologous to the outer membrane lipoprotein LolB. The second gene product had homology with a Haemophilus influenzae protein and was localized to the inner membrane of A. actinomycetemcomitans.

Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, a gram-negative bacterium, is strongly implicated as a causative agent of juvenile and adult periodontitis (21, 22, 27). Colonization of the oral cavity by A. actinomycetemcomitans and other oral pathogens may result in bleeding, loss of tissue matrix components, and ultimately tooth loss. A. actinomycetemcomitans expresses a number of virulence factors that are important in the disease process (7). Many of these virulence factors are proteins that are exported from the cytoplasm to the bacterial surface. These proteins may initially be directed to the surface of the bacterium by molecular information encoded in the signal sequence (26). The signal sequence is a transient extension of the NH2 terminus of the protein and is removed by enzymes following the translocation of the protein across the inner membrane.

A genetic system that identifies genes coding for exported proteins by using a truncated gene for alkaline phosphatase (phoA) that lacks a functional signal sequence has been developed (15). The system takes advantage of the fact that the translocation of alkaline phosphatase (PhoA) across the cytoplasmic membrane is required for enzymatic activity. Gene fusions between the coding region of heterologous signal sequences and phoA result in the expression of PhoA activity. We have utilized this genetic system to identify genes that code for exported proteins of A. actinomycetemcomitans.

Construction and screening of an A. actinomycetemcomitans DNA signal sequence library.

Cesium chloride-purified chromosomal DNA of A. actinomycetemcomitans SUNY 465 was restricted with Sau3A and separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA fragments corresponding to 300 to 600 bp were excised and purified by electroelution. The vector containing the truncated phoA (pHRM 104), provided by H. R. Masure (St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, Tenn.), was restricted with BamHI and ligated with the 300- to 600-bp Sau3A DNA fragments. Escherichia coli CC118 (phoA mutant) cells were transformed by electroporation with the ligation mixture and incubated in SOC medium (20) for 1 h. The cells were then plated on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates containing 500 μg of erythromycin per ml and 80 μg of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (XP) per ml.

Translocation of alkaline phosphatase across the bacterial inner membrane resulted in the hydrolysis of XP and the development of a blue colony phenotype. Approximately 2,500 individual colonies were screened, and 28 colonies were found to be PhoA+. These results indicate that fusion proteins were derived from plasmids containing an A. actinomycetemcomitans DNA sequence harboring a promoter, a translational start site, and a functional signal sequence. The presence of these sequences is based on the absence of an intrinsic promoter and signal sequence upstream from the phoA in the original plasmid (15). In addition, PhoA activity was indicative of the heterologous DNA sequence being in frame with the phoA for the translation of a functional protein.

Sequencing and protein homologs of PhoA+ colonies.

Plasmids from the PhoA+ colonies were isolated using Midi columns (Qiagen, Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.). An oligonucleotide primer (5′-AATATCGCCGTGAGC-3′) which hybridizes to the negative strand of phoA was used for sequencing the A. actinomycetemcomitans DNA contained on these plasmids. Plasmids were sequenced with a dideoxy terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif.) and analyzed with an Applied Biosystems automated DNA sequencer. DNA sequencing was performed in the Vermont Cancer Center DNA Analysis Facility. Unique sequences were determined for 24 of the 28 clones. The amino acid sequences deduced from selected DNA sequences are presented in Table 1. Most of the sequences contain a start methionine followed by amino acids that have features characteristic of prokaryotic signal sequences. A signal sequence typically has three distinct domains: an NH2-terminal positively charged region (1 to 5 amino acids), a central hydrophobic region (7 to 15 amino acids), and a more polar COOH-terminal domain (3 to 7 amino acids) adjacent to the mature protein. Most of the predicted sequences contain lysine residues followed by a run of amino acids rich in leucine and in other hydrophobic amino acids. Following the polar amino acids, a putative signal peptidase cleavage site can be predicted by the (−3,−1) rule of von Heijne (25, 26). Some plasmids (pVT1049 and pVT1057) contained sequences that did not fit the domain structure of typical signal sequences. These sequences may represent alternative secretory signals utilized for protein translocation.

TABLE 1.

Deduced amino acid sequences from selected PhoA+ clones

| Clone | Deduced amino acid sequencea |

|---|---|

| pVT1049 | AACHNKKLLMRCSPLVRISKSTSGSTNFIIWRNTMTNKSYSVAIVGLGAMGMGAAQSCIRAGLTTYGVD |

| pVT1051 | KLFMKKLKSYVLLVLAVLFLLTACVTD |

| pVT1057 | ATLRLIFKIRLNKERKMAYTIEEEQELTAIKAWWNENYKFIIVCFVIAFGGVFGWNYWQSHQIQKMHKASAEYEQALFNYQKD |

| pVT1063 | RTYCMKKSALALGVVVALGATWTGGAWYTGKVAETEFARQVDIANKD |

| pVT1064 | EDVLMTMKKTLLKHTALFAATLLAFSVQAKIITDVDGNQVDIPD |

| pVT1065 | VTKTKRRQRKQTMPQKVISSLNLKGARGMLKIKFKNWLTKTLVIFTALFAMQQVMAEDNPQTLTQQVSDKLFSDIKANQSRIKQD |

| pVT1067 | LTGKLFTMKPFLIKQSVIMKTQKLLAALLLGSVLAGCSAGCSSTID |

| pVT1068 | AIYQLAKGWLMKKFMLGMALGLGITLNANADIGTVKEGSGKILQGD |

| pVT1069 | TEFAISTLPTFGTMKKHLKKSPHFFCLTATILALAGCTPTIQLDTPKEGI |

Predicted amino-terminal positively charged regions of the signal sequence and mature protein sequences are in bold type. Predicted hydrophobic regions of the signal sequence are in bold type and italics. Predicted polar amino acid regions of the signal sequence are in bold type and underlined.

The deduced amino acid sequences were analyzed for protein homologs in the SwissProt database. High sequence homology or similarity to known proteins was found for 5 of the 24 clones analyzed (Table 2). The deduced proteins share sequences that are associated with precursors for surface or outer membrane proteins.

TABLE 2.

Protein homolog of PhoA+ clones

| Strain | % IDa | % SIMb | Homolog |

|---|---|---|---|

| pVT1051 | 52 | 76 | E. coli colicin precursor (24) |

| 52 | 71 | Saliva-binding protein of S. sanguis (6, 9) | |

| pVT1057 | 52 | 76 | Hypothetical transmembrane protein of H. influenzae HI0370 (8) |

| 66 | 66 | S. sanguis salivary-agglutinin receptor (5)c | |

| pVT1063 | 70 | 75 | Hypothetical protein of H. influenzae HI1236 (8) |

| 58 | 76 | Outer membrane protein A precursor of Serratia marcescens (4) | |

| pVT1064 | 64 | 68 | H. influenzae chaperone protein precursor HFB2 (GenBank no. P45991) |

| 38 | 63 | E. coli outer membrane porin protein precursor (2) | |

| pVT1067 | 60 | 85 | Murein lipoprotein precursor of E. coli (14) |

ID, identity.

SIM, similarity.

Based on a 15-amino-acid sequence in this protein.

Isolation of A. actinomycetemcomitans genes coding for exported proteins.

The genes corresponding to the DNA sequences identified on the PhoA+ clones were isolated from a λ EMBL3 A. actinomycetemcomitans DNA library with an average insert size of 15 kb. The library was generated by restriction of chromosomal DNA with Sau3A followed by separation by agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA fragments corresponding to 14- to 23-kbp fragments were isolated by electroelution, and the eluted fragments were ligated with λ EMBL3 arms restricted with BamHI. Phage was packaged with the Packagene in vitro system (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wis.) following the manufacturer's instructions. Phage containing A. actinomycetemcomitans DNA inserts was propagated by infection of E. coli LE392 grown in TYN medium (per liter, 10 g of tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract, 5 g of NaCl, NaOH to pH 7.2, 10 mM Tris [pH 7.2]) supplemented with 0.2% maltose and 0.01 M MgSO4.

Phage containing A. actinomycetemcomitans DNA was transferred to Hybond-N+ nylon membranes (Amersham Life Science, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, England). Following denaturation and neutralization, phage DNA was UV cross-linked to the membranes by using the Stratalinker 1800 (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and probed with signal sequence DNA. The library was screened using DNA probes labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by linear PCR. PCR products were generated using a primer corresponding to the start of the deduced signal sequence, with template DNA obtained by restriction of the PhoA+ clones with KpnI, which released the entire A. actinomycetemcomitans fragment. The PCR products were then purified by electroelution. The reaction was carried out in the presence of 200 μM (each) dTTP, dATP, and dGTP, with a limiting concentration of [α-32P]dCTP (3.4 μM). The reaction was allowed to proceed for 10 cycles in a thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.). The labeled probe was separated from unincorporated label by using Stratagene NucTrap probe purification columns. The 32P-probe was added to hybridization solution (20) and incubated with the membranes at 60°C. Membranes were washed in solutions of decreasing ionic strength at 60°C and exposed to X-ray film. Positive plaques were selected and purified by two additional rounds of plaque screening.

Recombinant phage DNA was isolated by the method of Sambrook et al. (20). DNA fragments containing signal sequences, as determined by Southern analysis, were isolated and cloned into the low-copy-number plasmid pHSG756 (23) or sequenced directly. Two of the five genes listed in Table 2 (pVT1051 and pVT1057) were isolated and sequenced. These genes were chosen based on sequence similarities to an adhesion molecule or receptor protein. The sequence of pVT1057 had limited sequence homology with the sequence for salivary-agglutinin receptor found on Streptococcus sanguis (5).

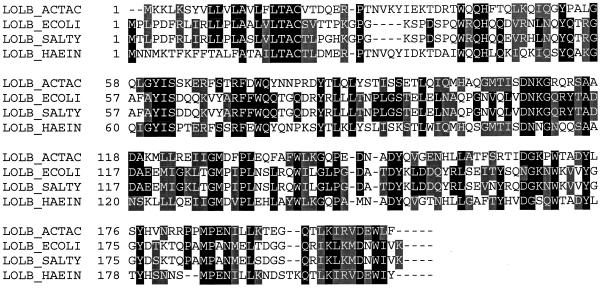

The complete gene sequence (corresponding to pVT1051), for which the initial deduced amino acid sequence demonstrated homology with either an E. coli colicin (24) or a saliva-binding protein from S. sanguis (6, 9), coded for a 207-amino-acid protein (23 kDa) that had protein homology with the outer membrane lipoprotein LolB (12). LolB is identical to the delta-aminolevulinate synthase (hemM) gene product (11). Protein homologs of LolB are found in several gram-negative organisms (Fig. 1). The Haemophilus influenzae protein is most similar to the LolB of A. actinomycetemcomitans, which displayed 60% identity and 72% similarity. The protein sequence contained a typical signal sequence with a putative signal peptidase cleavage site at amino acid 19. In addition to the signal sequence, the Leu-Thr-Ala-Cys sequence fits the consensus sequence for a lipoprotein box [Leu-(Ala,Ser)-(Gly,Ala)-Cys] (10). In this consensus sequence, which appears in all of the sequences in Fig. 1, the cysteine residue is covalently modified with diacylglycerol, and it becomes the amino terminal residue after cleavage of the signal peptide (17). The modified lipid probably intercalates the lipid bilayer. Biochemical studies have determined that the LolB of E. coli is synthesized as a precursor with a signal sequence that is subsequently processed to a lipid-modified mature form. In addition, evidence indicates that LolB (HemM) is involved in the localization of lipoproteins to the outer membrane of E. coli (12). The conservation of this protein across multiple species suggests that the protein has an important role in membrane formation.

FIG. 1.

Sequence alignment of LolB protein from A. actinomycetemcomitans. Identical residues are indicated by black shading, while conservative substitutions are indicated by gray shading. Alignment was determined by using Vector NTI software from InforMax, Inc., North Bethesda, Md. ACTAC, A. actinomycetemcomitans; ECOLI, E. coli (11); SALTY, Salmonella typhimurium (16); HAEIN, H. influenzae (8).

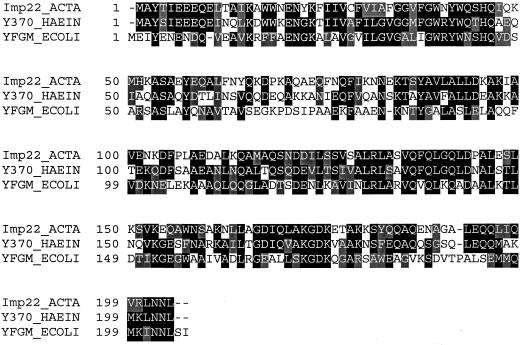

The complete A. actinomycetemcomitans gene corresponding to pVT1057 has 52% identity and 75% similarity at the amino acid level with a hypothetical transmembrane protein of H. influenzae HI0370 (8) (Fig. 2). This gene product is also predicted in E. coli. The gene codes for a 204-amino-acid protein (22.6 kDa), and the function of the protein has not been determined. Based on the predicted protein sequence, the protein lacks an apparent N-terminal signal sequence. Although there is a cysteine residue (amino acid 28) located at the amino terminus, the surrounding sequence does not conform to the lipoprotein consensus sequence as found in the LolB homolog. A transmembrane region has been identified between amino acids 24 (F) and 40 (W). A predicted coiled-coil region at the carboxyl terminus of the protein (18, 19) suggests that this protein may participate in specific binding interactions. Mutagenesis of this gene indicates that this protein is associated with the inner or cytoplasmic membrane of A. actinomycetemcomitans (13). Therefore, this 22-kDa protein has been designated Imp22 (inner membrane protein).

FIG. 2.

Sequence alignment of Imp22 protein from A. actinomycetemcomitans. Identical residues are indicated by black shading, while conservative substitutions are indicated by gray shading. Alignment was determined by using Vector NTI software from InforMax, Inc., North Bethesda, Md. ACTA, A. actinomycetemcomitans; YFGM_ECOLI, hypothetical 22.2-kDa protein of E. coli (3); Y370_HAEIN, hypothetical protein (HI0370) of H. influenzae (8).

In summary, gene fusion technology based on translational fusions with a signal sequence-deficient E. coli alkaline phosphatase that becomes active following passage across the cytoplasmic membrane has been used to identify exported proteins of A. actinomycetemcomitans. This approach has also been used to identify secreted and exported proteins from Streptococcus pneumoniae (15) and Helicobacter pylori (1). Most of the deduced amino acid sequences derived from the PhoA+ clones conformed to the three-domain organization of signal peptides. The remaining sequences may represent undefined signals for protein translocation in E. coli and A. actinomycetemcomitans. Based on the limited sequences, two complete A. actinomycetemcomitans genes that coded for potential inner or outer membrane proteins were isolated. In this study, genetic sequences that code for proteins that are postulated to be translocated across the cytoplasmic membrane are presented. It is our hypothesis that these proteins may be important in the pathogenesis of A. actinomycetemcomitans in human diseases. The generation of bacteria that are mutant for these gene products will help elucidate the role of these proteins in the biology of A. actinomycetemcomitans.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The complete DNA sequences for the genes represented by pVT1051 and pVT1057 can be obtained through GenBank under accession no. AF045460 and AF045461, respectively.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant RO1-DE09760.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bina J E, Nano F, Hancock R E. Utilization of alkaline phosphatase fusions to identify secreted proteins, including potential efflux proteins and virulence factors from Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;148:63–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blasband A J, Marcotte W R, Jr, Schnaitman C A. Structure of the lc and nmpC outer membrane porin protein genes of lambdoid bacteriophage. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:12723–12732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blattner F R, Plunkett III G, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D J, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun G, Cole S T. DNA sequence analysis of the Serratia marcescens ompA gene: implications for the organisation of an enterobacterial outer membrane protein. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;195:321–328. doi: 10.1007/BF00332766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demuth D R, Golub E E, Malamud D. Streptococcal-host interactions. Structural and functional analysis of a Streptococcus sanguis receptor for a human salivary glycoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:7120–7126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenno J C, LeBlanc D J, Fives-Taylor P. Nucleotide sequence analysis of a type 1 fimbrial gene of Streptococcus sanguis FW213. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3527–3533. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3527-3533.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fives-Taylor P, Meyer D, Mintz K. Virulence factors of the periodontopathogen Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J Periodontol. 1996;67:291–297. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.3s.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J F, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, et al. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganeshkumar N, Hannam P M, Kolenbrander P E, McBride B C. Nucleotide sequence of a gene coding for a saliva-binding protein (SsaB) from Streptococcus sanguis 12 and possible role of the protein in coaggregation with actinomyces. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1093–1099. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.3.1093-1099.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayashi S, Wu H C. Lipoproteins in bacteria. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1990;22:451–471. doi: 10.1007/BF00763177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikemi M, Murakami K, Hashimoto M, Murooka Y. Cloning and characterization of genes involved in the biosynthesis of delta-aminolevulinic acid in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1992;121:127–132. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90170-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuyama S, Yokota N, Tokuda H. A novel outer membrane lipoprotein, LolB(HemM), involved in the LolA (p20)-dependent localization of lipoproteins to the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1997;16:6947–6955. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.6947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mintz K P, Fives-Taylor P M. Construction and characterization of a strain of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans mutant for an inner membrane protein. J Dent Res. 1999;78:S133. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura K, Inouye M. DNA sequence of the gene for the outer membrane lipoprotein of E. coli: an extremely AT-rich promoter. Cell. 1979;18:1109–1117. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearce B J, Yin Y B, Masure H R. Genetic identification of exported proteins in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:1037–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Post D A, Hove-Jensen B, Switzer R L. Characterization of the hemA-prs region of the Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium chromosomes: identification of two open reading frames and implications for prs expression. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:259–266. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-2-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pugsley A P. The complete general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:50–108. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.50-108.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rost B, Sander C. Combining evolutionary information and neural networks to predict protein secondary structure. Proteins. 1994;19:55–72. doi: 10.1002/prot.340190108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rost B, Sander C. Prediction of protein structure at better than 70% accuracy. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:584–599. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slots J, Listgarten M A. Bacteroides gingivalis, Bacteroides intermedius and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in human periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 1988;15:85–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1988.tb00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slots J, Reynolds H S, Genco R J. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in human periodontal disease: a cross-sectional microbiological investigation. Infect Immun. 1980;29:1013–1020. doi: 10.1128/iai.29.3.1013-1020.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takeshita S, Sato M, Toba M, Masahashi W, Hashimoto-Gotoh T. High-copy-number and low-copy-number plasmid vectors for lacZ alpha-complementation and chloramphenicol- or kanamycin-resistance selection. Gene. 1987;61:63–74. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90365-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toba M, Masaki H, Ohta T. Primary structures of the ColE2-P9 and ColE3-CA38 lysis genes. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1986;99:591–596. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Heijne G. A new method for predicting signal sequence cleavage sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:4683–4690. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.11.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Heijne G. The signal peptide. J Membr Biol. 1990;115:195–201. doi: 10.1007/BF01868635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zambon J J. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in human periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1985.tb01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]