Abstract

Evidence from research and literature suggest that Eagle’s syndrome may present with a variety of symptoms creating diagnostic predicament amongst clinicians. We describe a detailed clinical review of symptomatology, diagnosis and management of hundred and one cases of stylalgia. The aim of our study was to asses effectiveness of intraoral styloidectomy as a definitive modality of treatment in stylalgia. A prospective clinical study was conducted in a tertiary referral centre and included 101 patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of stylalgia. The diagnosis of stylalgia was confirmed by history and clinical examination supplemented by orthopentomogram. All patients underwent intra oral styloidectomy following adequate trial of medical treatment. The success rate of intraoral styloidectomy was found to be 80. 19% i.e. 81 out of 101 patients were considered as cured based on pain assessment using visual analogue scale pre and post operatively. Though medical treatment can provide short term relief of symptoms, styloidectomy is the proven definitive modality of treatment for stylalgia.

Keywords: Eagle’s syndrome, Styloidectomy, Orthopentomogram, Visual analogue scale, Elongated styloid process

Introduction

Eagle’s syndrome refers to constellation of neuropathic and vascular occlusive symptoms caused by a pathological elongation of styloid process [1]. It was 1st described by Watt W. Eagle, an otolaryngologist at Duke University in 1937. The styloid process is a slender outgrowth at the base of the temporal bone, immediately posterior to the mastoid apex. It lies caudally, medially, and anteriorly towards the maxillovertebro pharyngeal recess which contains carotid arteries, internal jugular vein, facial nerve, glossopharyngeal nerve, vagus nerve, and hypoglossal nerve [2].

With the stylohyoid ligament and the small horn of the hyoid bone, the styloid process forms the stylohyoid apparatus, which arises embryonically from the Reicherts cartilage of the second branchial arch. Mineralisation or calcification of the styloid complex can cause elongated styloid process in 2–28% of general population [3].

Eagle defined the length of a normal styloid process as 2.5–3.0 cm. In 1937, Eagle described 2 possible clinical expressions attributable to elongated styloid process, as follows: the “classic Eagle syndrome” which is typically seen in patients after pharyngeal trauma or tonsillectomy, and it is characterized by ipsilateral dull and persistent pharyngeal pain, centred in the ipsilateral tonsillar fossa, that can be referred to the ear and exacerbated by rotation of the head. A mass or bulge may be palpated in the ipsilateral tonsillar fossa, exacerbating the patient’s symptoms. Other symptoms include dysphagia, sensation of foreign body in the throat, tinnitus, or cervicofacial pain [3].

The “second form” of syndrome (“stylocarotid syndrome”) is characterized by the compression of internal or external carotid artery (with their perivascular sympathetic fibres) by a laterally or medially deviated styloid process. It is related to a pain along the distribution of the artery, which is provoked and exacerbated by rotation and compression of the neck. It’s not correlated with tonsillectomy. In case of impingement of the internal carotid artery, patients experience referred supraorbital pain and parietal headache. In case of external carotid artery irritation, the pain radiates to the infraorbital region. Occasionally, it manifests as odynophagia, dysphonia, increased salivation, and headache [3].

Eagles syndrome is characterised by recurrent throat pain, sensation of foreign body in the pharynx, limitation of mouth opening, dysphagia, ipsilateral otalgia, tinnitus, trismus, cervical pain, reduced mobility particularly while moving the head to affected side, visual disturbances and recurrent syncope [1, 4–6]. These symptoms occurring due to an elongated styloid process can be attributed to various factors such as compression of glossopharyngeal, vagus or ramus of trigeminal nerve, impact on carotid vessels—carotidynia, degenerative changes in insertion of stylohyoid ligament, rheumatic styloiditis, fracture of ossified stylohyoid ligament or abnormal angulations of styloid process [4].

Diagnosis of Eagles syndrome is guided by clinical history, physical examination and radiographic evaluation. Intraoral palpation of styloid process is a very useful and specific test in clinical evaluation of stylalgia. This palpation recreates the specific neuralgic pain; a particular face and neck pain can be exacerbated by neck flexion, extension and contralateral rotation and helps in differentiating from temporomandibular joint arthralgias and other dysfunctions [7–9].

Various imaging techniques such as orthopentomogram, townes view, plain computed tomography, three dimensional computed tomography are used for confirming diagnosis of stylalgia. These offer a more objective parameter for evaluation of patients presenting with cervicofacial pain. Studies have estimated that in 2–28% of the general population there is radiographic evidence of an elongated styloid process, although symptoms are present in only some individuals [10].

Eagles syndrome can be treated pharmacologically, surgically or both. Though trial with anti inflammatory steroidal, antiepileptic drugs is given at initial presentation; however surgical shortening of styloid process is the proven definitive modality of treatment. Two major approaches for surgical excision of styloid are known: the extra oral approach and the classical transoral approach through fossa tonsillaris [4, 11–13]. Both have considerable advantages and disadvantages and should be performed individually in respect to the patient’s clinical profile and expertise of surgeon.

The diagnosis of stylalgia is likely to be missed due to the varied and non specific characteristics of symptoms and patients search for treatment within various specialities such as otolaryngology, dentistry, psychiatry and neurology. In present study we present our clinical and surgical experience with 101 cases of stylalgia treated by intraoral styloidectomy.

Materials and Methods

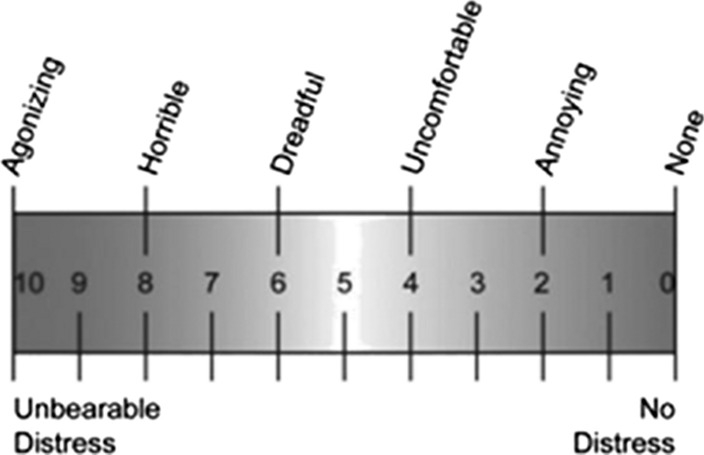

Hundred and one patients with symptomatic elongated styloid processes underwent surgical treatment between July 2006 and July 2016. A detailed medical history and clinical examination of the head and neck were undertaken on all patients. Physical examination included careful palpation of the tonsillar fossa, lateral pharyngeal wall, and the area between mastoid apex and mandibular angle in an attempt to precipitate the patient’s discomfort. Pain assessment was done using visual analogue scale, a numerical pictograph objective tool often employed for measurement of pain severity as shown in Fig. 1. Patients were asked to indicate the severity of pain felt according to a scale ranging from 0 to 10 Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Showing visual analogue scale used for the study

The diagnostic criteria established for surgical intervention were: palpable styloid process with tenderness, orthopentomogram showing styloid length > 2.5 cm or > 2/3rd of length of ramus of mandible Fig. 2 and cervicofacial pain radiating to ear. All patients received either gabapentine or carbamazepine at least for 2 months prior to considering surgery.

Fig. 2.

Orthopentomogram showing bilaterally enlarged styloid processes

An intraoral approach of styloidectomy was used for all patients. The operation was performed under general anaesthesia with patient in Roses position. Unilateral tonsillectomy was performed first, the tonsillar bed was palpated and tip of styloid process was identified. The superior constrictor muscle was separated longitudinally. Meticulous dissection was done in parapharyngeal space in order to avoid any neurovascular injury. After defining styloid process in entire length, its periosteum was incised and stripped from tip to base Fig. 3. The styloid process was fractured at base using rongeur and removed in toto. The tonsillar bed was sutured with absorbable suture material to prevent contaminaton by oropharyngeal secretions. All patients were hospitalized for at least 2 days post operatively. Patients were followed up for at least 3 months postoperatively and visual analogue scale was used for comparing pain before surgery and 3 months post surgery. The criteria to consider improvement was 50% reduction in pain on visual analogue scale in post operative period. All the patients who did not adhere to the follow up protocol were excluded from the study.

Fig. 3.

Intra oral exposure of styloid process

Results

A total of hundred and one patients with clinically and radiologically established diagnosis of elongated styloid process were included in this study. All these patients had undergone styloidectomy by intraoral trans-tonsillar approach. There were 90 females and 11 males within age range of 23–60 years (mean = 40 years).

Forty-two patients (41.5%) had bilateral symptomatic elongated process and underwent bilateral styloid process resection. Eighteen patients (17.8%) had unilateral symptomatic styloid, and underwent unilateral styloid process resection. Thirty-nine patients (38.6%) had bilateral palpable but unilaterally symptomatic styloid process; they underwent bilateral styloid process resection. Two patients (1.9%) had bilateral symptoms but unilateral resection was done as styloid was palpable only unilaterally during surgery. Thus total of 182 styloid processes were resected.

On Orthopentomogram the length of styloid processes ranged from 2.1 to 5.0 cm (mean 3.3 cm) and 166 out of 202 styloids had a length more than 2/3rd of the ramus of mandible Fig. 2. Pain on swallowing was the most common complaint present in 97 out of 101 patients (96%). The distribution of symptoms is illustrated in Table 1. Duration of patients’ symptoms ranged from 1 month to 48 months (mean-15 months). The postoperative follow up period ranged from 3 to 12 months.

Table 1.

Distribution of symptoms in current study

| Symptoms | Number and percentage of cases |

|---|---|

| Pain on swallowing | 97 (96%) |

| Radiation of pain to ear | 43 (42%) |

| Foreign body sensation in throat | 29 (28%) |

| Difficulty in swallowing | 12 (11%) |

Out of 101 patients operated 81 were considered improved on the basis of visual analogue scale for pain. If there was more than 50% decrease in intensity of pain post operatively, then patient was considered improved. Out of 42 patients having bilateral symptoms and operated for bilateral styloids, 27 showed improvement (64.2%). Out of 18 patients having unilateral symptoms and operated for unilateral styloid, 15 improved (83.3%), out of 39 patients having unilateral symptoms and operated for bilateral styloid 37 showed improvement (94.8%) and 2 patients having bilateral symptoms and operated for unilateral styloid both showed improvement (100%).

The data was analysed using statistical software SPSS version 20.0. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and/or median and range, and analyzed for normality by the Shapiro–Wilk test. The difference in pre and post test scores was expressed in terms of percentage reduction in post intervention scores. The comparison of scores was done using paired sample t test for data with normal distribution and if the data was not normally distributed, Wilcoxon signed rank test was used. All tests were two-tailed and a p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of pre and post operative scores

| Parameters | Mean | Standard deviation | Median | Interquartile range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre intervention Scores | 7.93 | 1.85 | 8 | 2 |

| Post intervention Scores | 2.73 | 2.35 | 2 | 3 |

| % difference in post to pre intervention scores | 65.23 | 31.47 | 71.43 | 37.5 |

| P value | < 0.001 |

The median pre intervention scores were 8 (2 IQR), while the median post intervention scores were 2. The median percentage reduction from pre to post intervention score was 71.43% and this difference was statistically significant (p = 0.001) suggesting that the intervention was highly effective in reducing the post operative scores compared to pre operative scores.

Discussion

The term styloid process is derived from the word ‘stylos’ meaning a pillar. The styloid process is a cylindrical bone which arises from the temporal bone in front of stylomastoid foramen. It is derived embryologically from second branchial arch along with stylohyoid ligament and lesser cornu of hyoid. The stylohyoid apparatus is formed by styloid process with its various attachments which include stylopharyngeus, styloglossus, stylohyoid muscles; stylohyoid and stylomandibular ligaments; and lesser cornu of hyoid [4]. It lies in the parapharyngeal space between internal and external carotid artery. The internal jugular vein, accessory nerve, glosspharyngal nerve, hypoglossal nerve, vagus nerve, internal carotid artery and sympathetic chain lie medial to it. The entire stylohyoid apparatus is derived from 4 segments: (1) Tympanohyal base of styloid process, (2) Stylohyal—shaft of styloid process, (3) Ceratohyal—stylohyoid ligament, and (4) Hypohyal—lesser cornu of hyoid [14].

The elongation of styloid process is not uncommon, but the true Eagles syndrome is a rare disease. Eagle reported the incidence of elongated styloid process as 4% out of which only 4% were found to be symptomatic [15]. Similarly, Bozkir et al. [10] reported incidence of elongated styloid process as 4% and Kauffman reported incidence of 28%.

Majority of patients with an elongated styloid process are asymptomatic and do not need any treatment. When symptoms exist the severity often doesn’t correlate with the length of styloid process [8]. Steinman et al. [16] has proposed three theories for elongation of styloid process: theory of reactive metaplasia which states that it is a part of post traumatic healing process, theory of reactive hyperplasia which explains that trauma can cause such ossification and theory of anatomical variance which considers it to be normal anatomical variation.

The normal length of the styloid process varies greatly, as follows: ~ 2.5 cm according to W W Eagle [15], from 1.52 to 4.77 cm according to Moffat et al. [17], Less than 3 cm according to Kaufman et al. [18], from 2 to 3 cm, according to Lindeman [19], Less than 2.5 cm according to Correl et al. [20], Langlais et al. [21] and Montalbetti et al. [22], Less than 4 cm according to Monsour and Young [23]. In our study the length of styloid process was measured in a similar method as described by Ilguy et al. [24], as the distance from the point where the styloid process left the tympanic plate to the tip of styloid process irrespective of whether or not the styloid process was segmented. We measured elongated styloid processes in 101 patients using OPG and the mean length of styloid process was found to be 3.3 cm. No correlation was found between the length of styloid process and severity of symptoms. [3, 7].

In panoramic view the styloid process is visualised posterior to the external acoustic meatus, with a descendant and anterior trajectory. When elongated it attains over one-third of the length of mandibular ramus [25]. In our study 166 out of 202 of styloid processes were more than 1/3rd of length of the ramus of mandible. Various theories have been proposed to explain the causes of styloid process elongation, such as trauma (amygdalectomy, coughing, epileptic attack), secondary ossification of an embryonic shoot after segmentation of reichters cartilage, stylohyoid ligament calcification and early menopause [26, 27].

The incidence of Eagle’s syndrome has been reported to be higher in females [28]. In present study 89 patients out of 101 were females. The exact cause of female predominance is not known. It could be related to the endocrine changes occurring in peri-menopausal period accompanied by ossification of ligaments elsewhere like iliolumbar ligament, thyrohyoid ligament etc. [29].

In a study conducted by Alper Ceylan et al. (2008) on 61 cases of Eagles syndrome 23 (37.7%) had bilateral while 38 patients (62.3%) had unilateral symptoms [30]. In the present study, 44% and 56% patients presented with bilateral and unilateral symptomatic styloid enlargement respectively. Although styloid process elongation is seen bilaterally in most cases, patients are usually symptomatic unilaterally for stylalgia despite of bilateral elongation [31].

Clinically stylalgia is known to occur commonly after 30 years of age [3]. Some studies report it to be more common in elderly, which could be due to age related calcification of ligaments and processes due to reactive hyperplasia or metaplasia or anatomical variance. [16] In our study the mean age of presentation was found to be 40 years.

Stylalgia is characterised by dull constant nagging recurrent pain in the oropharynx sometimes radiating to ear, cheek, eye, jaw, neck, infraorbital, infratemporal, occipital area. Other common symptoms include dysphagia, globus pharyngis, odynophagia or pain with rotation of head [13, 32]. In a review of 61 cases of Eagles syndrome by Ceylan et al. [30], 52 patients presented with throat pain, 47 with otalgia, 37 with foreign body sensation in throat, 35 with cervical pain and 22 with facial pain. In another review of 52 cases by Harma et al. [33], 22 reported pain in the neck and 19 reported pain in the throat. In present study, pain while swallowing was most common complaint [97% cases] followed by throat pain radiating to ear [42%], foreign body sensation in throat [28%] and difficulty in swallowing [24%].

An elongated styloid process causes its spectrum of symptoms by various mechanisms as follows: [28, 34]

(1) Compression of glossopharyngeal nerve and sometimes lower branches of trigeminal and chorda tympani nerve, (2) fracture of the ossified stylohyoid ligament, (3) impingement on the carotid artery and its sympathetic plexus, (4) insertion tendinosis, (5) Post Tonsillectomy fibrotic entrapment neuropathy of neighbouring cranial nerves.

Eagle described two types of stylalgia: classic styloid syndrome and stylocarotid syndrome. The former resulted from compression of cranial nerves mainly glossopharyngeal nerve resulting in pain in throat and neck. Pain may be due to proliferation of granulation tissue secondary to trauma leading to subsequent ossification as suggested by Murtagh et al. [35]. However we differ with this theory of formation of granulation tissue as in none of our cases granulations were encountered. Also, researchers have not found any correlation between degree of ossification and severity of symptoms and, most cases of stylalgia do not give history of tonsillectomy or any cervicofacial trauma [3, 36]. In a clinical study conducted by Prasad et al. [37] on 58 patients with stylalgia none had any positive history of trauma or surgery. In our study too, none of the patients had any significant history of trauma. It’s now believed that such trauma is not likely cause for ossification of stylohyoid apparatus [36].

In the stylocarotid syndrome, styloid process causes compression of internal or external carotid artery leading to transient ischaemic attacks, parietal cephalgia etc. [38]. It should be remembered that carotidynia can be caused by styloid process which is not elongated but deviated too medially or laterally [39].

Eagle’s syndrome is diagnosed clinically by digital palpation of tonsillar fossa whereby a sharp elongated hard structure is felt directed antero-medially. The diagnosis can be further confirmed by injection of 2% lignocaine in tonsillar fossa, following which patient reports decrease in pain [37]. Though different imaging techniques are available to asses’ elongated styloid process, the conventional panoramic view is the preferred radiological examination in our department as it demonstrates elongated styloid process clearly and effective dose of radiation is low (0.002 mSv) [40, 41]. A spiral CT can illustrate anatomy of styloid process in more detail and is the most advanced diagnostic imaging technique as it gives detailed information about the course and relations of stylohyoid chain and important adjacent structures; length and angulations [34]. However the effective dose of radiation is much higher (1.890.2 mSv) than OPG [1] and slight movement can degrade the images [7]. Reported radiographic prevalence of elongated styloid process varies from 2 to 30% [10, 42–44].

Eagles syndrome can be managed conservatively, surgically or both. Non surgical modalities of treatment include reassurance, NSAIDS, steroids, gabapentine, carbamazepine, pregabaline, tianeptine, amitrypyline, physiotherapy, injection of long acting local anaethetic and/or stellate ganglion block [16, 45]. Clinical research has revealed that there is no consistent long term relief with conservative treatment and symptoms recur within 6 to 12 months after conservative treatment [8, 46]. The most satisfying and effective method to eliminate the symptoms caused by an elongated styloid process is its surgical shortening [13, 15]. Different types of transoral and extra-oral surgical approaches are described which includes retromolar, paratonsillar, trans-tonsillar approach, transcervial, preauricular and endoscopic assisted styloidectomy with or without navigation [47].

The main advantage of extra-oral approach is the adequate exposure of styloid process and adjacent structures which help avoid any neurovascular injury. Also this sterile surgical technique decreases the possibility of surgical site infection [48]. However major disadvantage of this approach is cosmetic deformity resulting from scar. Other drawbacks include extensive facial dissection, uncomfortable paraesthesia of cutaneous nerves such as greater auricular nerve and longer duration of surgery [4, 9, 17, 19, 37].

On the contrary intraoral approach is easy to perform, leaves no external scar, its operating and recovery time is shorter. However some otolaryngologist find this approach more challenging as poor visualisation increases the chances of iatrogenic injury to nerves. This procedure involves dissection in the pharynx up to deep cervical fascia which may increase chances of deep neck space infection. Rare disadvantages of this technique include poor haemorrhage control, alterations of speech and swallowing, postoperative edema, decreased jaw opening and short lasting mucosal edema at the operative site [48]. However in our study all styloidectomies were performed by intraoral approach and all cases were uneventful during intra and post operative period.

Prasad et al. [37] reported 58 cases of eagles syndrome treated by transoral styloidectomy without any complication. Similarly Ghosh et al. [49] reported series of 35 cases treated successfully with intraoral approach. In our review of 101 patients treated by transoral styloidectomy none were found to have any intraoperative or post operative complication. The success rate of surgery in our study was found to be 80% [81 out of 101 patients improved] which was statistically significant with p value = 0.001. Cure rates in literature have been reported to be between 80 and 100% [50]. Hence we advocate transoral styloidectomy as an efficient technique for surgical treatment of Eagles syndrome.

We recommend simple precautions which if followed intra-operatively can prevent complications which include maintenance of clear field by cauterisation of small vessels by using bipolar cautery which will facilitate better visualisation and minimise neurovascular trauma, longitudinal dissection in the tonsillar bed and suturing of tonsillar bed postoperatively with absorbable suture to prevent deep neck space infection. The possible cause of recurrence of symptoms in 20% patients could be entrapment of adjoining nerves in fibrous tissue. Thorough knowledge of anatomy and surgeons expertise also influences the outcome of surgery.

Conclusion

Eagle’s syndrome is often misdiagnosed and treated for a long duration as functional temporomandibular joint dysfunction or non specific glossopharyngeal, occipital or sphenopalatine neuralgia. The other common differential diagnosis include salivary gland disease, chronic tonsillitis, tumors of pharynx and tongue base, laryngopharyngel reflux, atypical migraine, carotidynia, otitis externa, temporal arteritis etc. Moreover patients may be apprehensive about possibility of malignancy in this region. Given to the variations of clinical presentation of Eagles syndrome, a careful recording of patient’s history and current clinical symptoms aided by radiological evaluation is necessary. Shortcomings of pharmacotherapy are well known in literature hence once diagnosed, resection of styloid process by appropriate surgical approach is necessary. Intraoral approach is a safe surgical alternative for management of stylalgia and provides significant relief from troublesome symptoms.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not for profit sectors.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guidelines [Goa Medical College Ethical committee guidelines] on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was taken from all participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Valerio CS, Peyneau PD, de Sousa AC, Cardoso FO, de Oliveira DR, Taitson PF, Manzi FR. Stylohyoid syndrome: surgical approach. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23(2):138–140. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824cdb46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagoji I, Hadimani G, Patil B, et al. Bilateral elongated styloid process its anatomical embryological and clinical implications. Int J Med Res Health Sci. 2013;2(2):273–276. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grossman JR, Tarsitano JJ. The styloidstylohyoid syndrome. J Oral Surg. 1977;35:555–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chrcanovic BR, Custódio AL, De Oliveira DR. An intraoral surgical approach to the styloid process in Eagle’s syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;13(3):145–151. doi: 10.1007/s10006-009-0164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blythe JN, Matthews NS, Connor S. Eagle’s syndrome after fracture of the elongated styloid process. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;47(3):23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kay DJ, HarEl G, Lucente FE. A complete stylohyoid bone with a stylohyoid joint. Am J Otolaryngol. 2001;22(5):358–361. doi: 10.1053/ajot.2001.26497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yetiser S, Gerek M, Ozkaptan Y. Elongated styloid process: diagnostic problems related to symptomatology. Cranio. 1997;15(3):236–241. doi: 10.1080/08869634.1997.11746017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fusco DJ, Asteraki S, Spetzler RF. Eagle’s syndrome: embryology, anatomy, and clinical management. Acta Neurochir. 2012;154:1119–1126. doi: 10.1007/s00701-012-1385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diamond LH, Cotrell DA, Hunter MJ, Papageorge M. Eagle’s syndrome: a report of 4 patients treated using a modified extraoral approach. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:1420–1426. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.28276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bozkir MG, Boga H, Dere F. The evaluation of styloid process in panoramic radiographs in edentulous patients. Turk J Med Sci. 1999;29(2):481–485. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fini G, Gasparini G, Filippini F, Becelli R, Marcotullio D. The long styloid process syndrome or Eagle’s syndrome. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2000;28(2):123–127. doi: 10.1054/jcms.2000.0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin TJ, Friedland DR, Merati AL. Transcervical resection of the styloid process in Eagle syndrome. Ear Nose Throat J. 2008;87(7):399–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strauss M, Zohar Y, Laurian N. Elongated styloid process syndrome: intraoral versus external approach for styloid surgery. Laryngoscope. 1985;95(8):976–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rathwa A, Dharati M, Kumar S. Study of styloid process: anatomical variation in length, angulation and distance between two styloid processes. Int J Recent Trends Sci Technol. 2013;8(2):109–112. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eagle WW. Elongated styloid process report of two cases. Arch Otolaryngol. 1973;25(5):584–587. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1949.03760110046003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinman EP. Styloid syndrome in absence of an elongted process. Acta Otolaryngol. 1968;66:347–356. doi: 10.3109/00016486809126301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moffat DA, Ransden RT, Shaw HJ. The styloid process syndrome: aetiological factors and surgical management. J. Larygol Otol. 1977;91(4):279–294. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100083699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaufman SM, Elzay RP, Irish EF. Styloid process variation. Radiologic and clinical study. Arch Otolaryngol. 1970;91:460–463. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1970.00770040654013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindeman P. The elongated styloid process as a cause of throat discomfort. Four case reports. J Laryngol Otol. 1985;99(5):505–508. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100097139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Correll RW, Jensen JL, Taylor JB, Rhyne RR. Mineralization of the stylohyoidstylomandibular ligament complex. A radiographic incidence study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1979;48(4):286–291. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(79)90025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langlais RP, Miles DA, Van Dis ML. Elongated and mineralized stylohyoid ligament complex: a proposed classification and report of a case of Eagle’s syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;61:527–532. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90400-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montalbetti L, Ferrandi D, Pergami P, Savoldi F. Elongated styloid process and Eagle’s syndrome. Cephalalgia. 1995;15(2):80–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1995.015002080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monsour PA, Young WG. Variability of the styloid process and stylohyoid ligament in panoramic radiographs. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;61(5):522–526. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90399-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Igluy M, Igluy D, Guler N, Bayirli G. Incidence of the type and calcification patterns in patients with elongated styloid process. J Int Med Res. 2005;33(1):96–102. doi: 10.1177/147323000503300110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.More CB, Asrani MK. Evaluation of the styloid process on digital panoramic radiographs. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2010;20(4):2615. doi: 10.4103/0971-3026.73537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mortellaro C, Biancucci P, Picciolo G, Vercellino V. Eagle’s syndrome: importance of a corrected diagnosis and adequate surgical treatment. J Craniofac Surg. 2002;13(6):7558. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim E, Hansen K, Frizzi J. Eagle syndrome: case report and review of the literature. Ear Nose Throat J. 2008;87(11):6313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singhania AA, Chauhan NV, George A, Rathwala K. Lidocine infiltration test: an useful test in the prediction of results of styloidectomy for Eagle’s syndrome. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;65(1):20–23. doi: 10.1007/s12070-012-0577-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epifanio G. Long styloid processes and ossification of stylohyoid chain. Rad Prat. 1962;12:127–132. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ceylan A, Köybaioğlu A, Çelenk F, Yilmaz O, Uslu S. Surgical treatment of elongated styloid process: experience of 61 cases. Skull Base. 2008;18(5):289–295. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1086057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malik JN, Monga S, Sharma AP, Nabhi N, Naseeruddin K. Stylalgia revisited: clinical profile and management. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;30(6):335–340. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun CK, Mercuri V, Cook MJ. Eagle syndrome: an unusual cause of head and neck pain. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(2):294–295. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hӓӓrma R. Stylalgia: clinical experiences of 52 cases. Acta Otolaryngol. 1966;224:149–155. doi: 10.3109/00016486709123570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naik SM, Naik SS. Tonsillo styloidectomy for Eagle’s syndrome: a review of 15 cases in KVG Medical College Sullia. Oman Med J. 2011;26(2):1221–1226. doi: 10.5001/omj.2011.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murtagh RD, Caracciolo JT, Fernandez G. CT findings associated with Eagles syndrome. Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(70):1401–1402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Camarda AJ, Deschamps C, Forest D. Stylohyoid chain ossification: a discussion of etiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:508–514. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(89)90264-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prasad KC, Kamath MP, Reddy KJ, Raju K, Agarwal S. Elongated styloid process (Eagle’s syndrome): a clinical study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:171–175. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.29814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakagawa D, Ota T, Lijima A, Saito N. Diagnosis of Eagles syndrome with 3 dimensional angiography and near infrared spectroscopy: case report. Neurosurgery. 2011;68:E847–E849. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318207ac74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farhat HI, Elhammady MS, Ziayee H, Aziz Sultan MA, Heros RC. Eagle syndrome as a cause of transient ischemic attacks. J Neurosurg. 2009;110(1):90–93. doi: 10.3171/2008.3.17435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorenzen M, Wedegartner U, Weber C, Lockemann U, Adam G, Lorenzen J. Dose optimisation for multislice computed tomography protocols of the mid-face. Diagn Intervent Radiol. 2005;177:2651. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-813951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sadaksharam J, Singh K. Stylocarotid syndrome: an unusual case report. Contemp Clin Dent. 2012;3(4):5036. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.107456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gokce C, Sisman Y, Tarim Ertas E, Akgunlu F, Ozturk A. Prevalence of styloid process elongation on panoramic radiography in the Turkey population from Cappodocia region. Eur J Dent. 2008;2(1):18–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keur JJ, Campbell JP, McCarthy JF, Ralph WJ. The clinical significance of the elongated styloid process. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;61:399–404. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Erol B. Radiological assessment of elongated styloid process and ossified stylohyoid ligament. J Marmara Univ Dent Fac. 1996;2:554–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scheller K, Eckert AW, Scheller C. Transoral, retromolar, paratonsillar approach to the styloid process in 6 patients with Eagle’s syndrome. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2014;19(1):e61–e66. doi: 10.4317/medoral.18749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gervickas A, Kubilius R, Sabalys G. Clinic, diagnostics and treatment peculiarities of Eagle’s syndrome. Stomatol Bal Dent Maxillofac J. 2004;6:11–13. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maru YK, Patidar K. Stylalgia and its surgical management by intra oral route clinical experience of 332 cases. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;55(2):8790. doi: 10.1007/BF02974610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chase DC, Zarmen A, Bigelow WC, McCoy JM. Eagle’s syndrome: a comparison of intraoral versus extraoral surgical approaches. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;62(6):625–629. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90253-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ghosh LM, Dubey SP. The syndrome of elongated styloid process. Auris Nasus Larynx. 1999;26(2):169–175. doi: 10.1016/s0385-8146(98)00079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Colby CC, Del Gaudio JM. Stylohyoid complex syndrome: a new diagnostic classification. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137(3):248–252. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2011.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]