Abstract

The aim is to compare two commonly performed surgical techniques, lateral resection and crushing for Concha Bullosa (CB) as auxiliary management in patients who underwent septoplasty. In Patients diagnosed with DNS and CB, using endoscopy and Computerized Tomography, NOSE score was calculated. All patients underwent septoplasty and depending upon the surgical method followed for CB, patients allotted in two groups. In group A, crushing of middle turbinate was performed using Blakesley forceps and in group B, lateral resection of CB was done. Postoperative NOSE scores were calculated at 6 months and outcomes were compared. Both the surgical methods were highly effective in the management of CB. All patients had significant improvement in the NOSE score when compared with the preoperative values. Two patients in group B developed synechia between the turbinate and lateral wall. However, the superiority of one method over the other could not be established statistically. CB is a common anomaly in anatomy of nose and paranasal sinus. It frequently coexists with DNS and may cause sinus problems if it is over-pneumatised. In such cases, surgical correction is warranted. Crushing of MT and lateral resection are two commonly performed methods, both are equally effective, but the crushing technique has an advantage of mucosal preservation and less postoperative complications.

Keywords: Concha bullosa, Lateral resection, Crushing technique, NOSE score, Septoplasty

Introduction

Concha bullosa (CB), pneumatization of the middle turbinate (MT), is one of the most common anatomical variants associated with the nose and paranasal sinus. The incidence of this sinonasal anatomy variation is reported to be between 14 and 53% [1]. Though it is mostly asymptomatic, it can cause serious problems in the case of over-pneumatization. Infection from the ethmoid and frontal sinus can involve the CB, resulting in mucocele formation [2] The CB may be so enlarged that it can fill the gap between the septum and lateral wall, creating mucosal contact and narrowing the middle meatus resulting in obstruction of sinus drainage, leading to sinusitis [3].

Controversies exist between authors regarding the association of CB with Deviated Nasal Septum [4]. However, some authors have demonstrated a strong relationship between the presence of large CB and contralateral DNS [1, 5].

There are various methods reported to correct the anatomical defect surgically such as partial resection of the lateral part of the middle turbinate, total resection of MT, crushing, and Submucosal resection. But, there is no clear consensus about the procedure of choice with the best results [6]. Previously a study has been conducted to evaluate the effect of the two surgical procedures (lateral turbinectomy and crushing method) on olfactory function, using the Brief Smell Identification Test (BSIT) [7]. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first comparing the effect of these two most common auxiliary procedures performed for CB with septoplasty, focusing its effect on nasal obstruction.

NOSE Scale (Nasal obstruction and symptom evaluation) is a well-validated, reliable instrument for evaluation of nasal obstruction. It consists of brief and easy to complete five self-answered questions by the patient. Each question is graded using a Likert scale from 0 (Asymptomatic) to 4 (Severe problem), the scores are summed up and multiplied by 5 to obtain a final score. It is used to compare the health-specific outcomes of the disease [8]. The scale has been extensively used in international literature for objective assessment of nasal obstruction in post septoplasty and FESS patients [6, 9, 10].

Materials and Methods

The prospective study was conducted at a tertiary care center in South India, after obtaining permission from hospital authority. Patients presenting to the Out-Patient Department with unilateral or bilateral nasal obstruction underwent detailed ENT examination including anterior rhinoscopy and Diagnostic Nasal Endoscopy (DNE) after careful history taking and noting the demographic profile. Computerized Tomography of Nose and Paranasal sinus (CT PNS) was carried out using 0.6 mm cuts (GE Optima) in patients with a deformed septum and middle turbinate hypertrophy. The preoperative NOSE score for patients with a diagnosis of Deviated Nasal Septum (DNS) with Concha bullosa was calculated (Table 1).

Table 1.

NOSE Scale (8)

| Characteristic | Asymptomatic | Very mild | Moderate | Fairly bad | Severe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal blockage/obstruction | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Trouble breathing through the nose | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Trouble sleeping | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Unable to get enough air through during exertion | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Mouth breathing | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

P value: NS = Non-significant (P-value > 0.05), S = significant (P-value ≤ 0.05 HS = highly significant (P-value ≤ 0.001)

A total of 24 participants were selected for the study. After taking written informed consent, patients were posted for elective surgery under general anaesthesia. All of them underwent a septoplasty. Based on the adjunct surgical procedure for Concha Bullosa, the cases were divided into two equal groups. Patients in which middle turbinoplasty was done by crushing technique were included in group A, whereas those who underwent lateral laminectomy were placed in group B. In patients with bilateral disease, the side which had severe nasal obstruction was considered for turbinate surgery.

Inclusion criteria

Patients operated with septoplasty and middle turbinate surgery (crush or lateral laminectomy) were included in the study.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients with bilateral surgery, any other adjunct procedures like inferior turbinate surgery, other surgical methods followed for the management of Concha Bullosa, and patients who were not available for follow-up were excluded from the study.

Surgical Method

After proper positioning, local infiltration with 2% xylocaine and 1:200,000 adrenaline was done. Septoplasty was performed in all cases followed by middle turbinoplasty. After local infiltration, the middle turbinate was gently crushed using a Blunt Blakesley forceps with minimal or no damage to overlying mucosa. In the lateral laminectomy technique, a Sickle knife or blade was used to give deep incision in the anterior part of the middle turbinate; the lateral bony part of the turbinate was gently separated till the posterior end. The lateral part was then removed using a thru-cut instrument. Nasal packing was done on the operated side. The pack was removed on 1st postoperative day. Nasal douching was done with saline and the patient was followed up after 1 week,1 month, and after 6 months.

At 6 months postoperatively, patients were assessed using the NOSE Scale (Nasal obstruction and symptom evaluation) and results were compared between the two techniques with the preoperative scores.

Statistical Method

Statistics and data analysis related to the study was done using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS V 16). Mean value and Standard Deviation (SD) were used for quantitative data and Frequency and percentage for qualitative data. Paired and Unpaired Student t-test was used to compare the mean between related and independent groups in quantitative data respectively.

Results

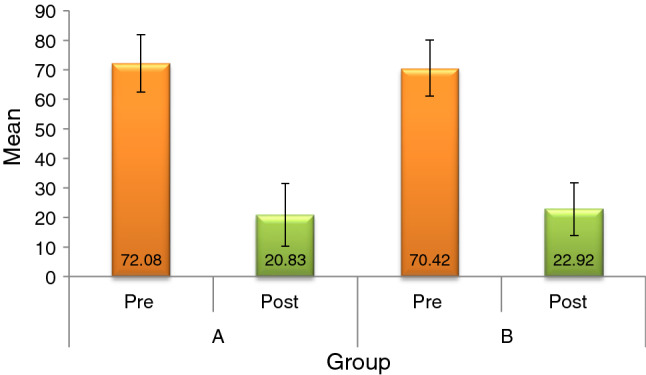

Twenty-four patients were selected to present in this article after evaluating the study criteria. Twelve patients were included in Group A, out of which five patients (41.66%) were female. Group B comprised of three (25%) females. All patients were between 18 and 65 years of age. Both the groups were comparable according to the demographic characteristics (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Mean Score, SD and P-value

| Status | Group | N | NOSE Score (Mean) | Std. Deviation (SD) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-operative | A | 12 | 72.08 | 9.64 | < 0.001 HS |

| B | 12 | 70.41 | 9.40 | ||

| Postoperative | A | 12 | 20.83 | 10.62 | < 0.001 HS |

| B | 12 | 22.91 | 8.90 |

P value: NS = Non-significant (P-value > 0.05), S = significant (P-value ≤ 0.05 HS = highly significant (P-value ≤ 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Comparing the preoperative and postoperative NOSE scores in both the groups

In our study, all patients had significant improvement in the NOSE score after 6 months postoperatively (p value < 0.001). Comparing the scores of the two groups preoperatively, the mean value was 72.8 in group A and 70.42 in group B. postoperative mean values were 20.83 ± 10.62 and 22.91 ± 8.90 in group A and Group B respectively. Both of the procedures were highly effective (p < 0.001). Two patients developed postoperative synechia in group B. However, the superiority of the two surgical procedures over one another was not established statistically in the study.

Discussion

Concha bullosa is mainly seen in the middle turbinate due to its pneumatization. In the lamellar type, the pneumatization is limited to vertical lamella; the bulbous type is the pneumatization of the inferior bulbous portion, and those in which is the pneumatization of both the lamellar and bulbous parts of the middle turbinate is called extensive Concha bullosa [11]. It was also observed that large CB, specifically bullous type can cause narrowing of the middle meatus and infundibulum causing recurrent sinusitis. There are various techniques followed to correct the anatomical defect, but there is no clear consensus regarding the procedure of choice. The most common surgical methods followed are lateral laminectomy, submucosal resection, and crushing of MT [12]. In this study, we compared the postoperative outcome of lateral laminectomy and crushing of MT as an adjunct procedure in septoplasty. The effectiveness of the two methods was done by using the NOSE instrument, which is an extensively tested and validated set of questionnaires for nasal obstruction developed by Stewart et al. [6].

In this study, five patients (41.66%) were female in group A. Group B comprised of three (25%) females. Similar findings of male predominance were found in the study conducted by Mehta et al. [13]. However, another study states that CB is more common in females [14]. The disparity may be due to the small sample size and selection criteria of the study. The chief complaint of patients in both the groups was unilateral or bilateral nasal obstruction. On endoscopic and radiological investigation, all patients had DNS with unilateral or bilateral CB. All patients underwent septoplasty and turbinate surgery. In bilateral CB cases, the side having large CB was preferred for surgery. We found out that in seven (29%) cases the DNS was contralateral to the large CB. This is in congruence with the study done by Stallman et al. [1]. Both surgeries were highly successful in the respective groups (P-value < 0.001 HS). Though Group B patients who underwent lateral laminectomy of MT had slightly better subjective improvement than Group A patients (Crushing technique), the difference was not statistically significant. Similar results were obtained in the study by Andaloro et al. [15]. Nevertheless, lateral resection of MT was associated with more intra-operative bleeding and synechia formation was noted between the turbinate and lateral wall in two (16.66%) patients on the follow-up visit. Early endoscopic release of the synechia was performed in the out-patient department. In group B patients no such complications were seen as the crushing procedure causes minimal mucosal damage and both the anatomy and physiology of middle turbinate are well preserved. It is also expected that the intact turbinate mucosa in the crushing method can cause rapid healing as compared to the lateral resection of MT [16].

Conclusion

CB is a common finding in ENT practice. Most cases of CB do not require any surgical intervention. It is sometimes necessary to correct the defect when it is large and bullous and causes obstruction. Many studies have demonstrated the coexistence of CB with DNS. Common surgical methods for CB are the crushing of MT and resection technique. There is no statistical difference in the effectiveness of both the surgeries as an adjunct to septoplasty. However, the crushing of the turbinate has the advantage of preserving the mucosa and less post-operative complications. Though many surgeons prefer lateral resection over crushing in the case of large CB, more complications are anticipated in the resection technique. So, in our opinion, the choice of surgical procedure should be individualized based on patient findings.

Funding

No funding was received from any source.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Ethics Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from Institute ethical committee.

Consent to Participate

Written informed consent from the participants were taken.

Consent for Publication

Verbal consent for publication from each participant was obtained.

Availability of Data and Material

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Code Availability

Code availability not applicable to this article as no new codes were created.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Stallman JS, Lobo JN, Som PM. The incidence of concha bullosa and its relationship to nasal septal deviation and paranasal sinus disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25(9):1613–1618. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lidov M. Inflammatory Disease Involving a Concha Bullosa (Enlarged Pneumatized Middle Nasal Turbinate): MR and CT Appearance. :3. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Stammberger H, Wolf G. Headaches and sinus disease: the endoscopic approach. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;97(5_suppl):3–23. doi: 10.1177/00034894880970S501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhandary SK, Kamath PSD. Study of relationship of concha bullosa to nasal septal deviation and sinusitis. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;61(3):227–229. doi: 10.1007/s12070-009-0072-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Senior Resident in Deptt. Of Radiodiagnosis & Imaging, Government Medical College, Srinagar., Shiekh Y, Ali A, Resident in deptt. of ENT, Head & Neck Surgery , Government Medical College, Srinagar., Lone A, Specialist in ENT ,Head & Neck Surgery, District Hospital Baramulla., et al. CONCHA BULLOSA AND ITS ASSOCIATION WITH DNS AND SINUSITIS. IJAR. 2017 Oct 31;5(10):362–7.

- 6.Stewart MG, Smith TL, Weaver EM, Witsell DL, Yueh B, Hannley MT, et al. Outcomes after nasal septoplasty: results from the Nasal Obstruction Septoplasty Effectiveness (NOSE) study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(3):283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Comparison of the Effects of 2 Surgical Techniques Used in the Treatment of Concha Bullosa on Olfactory Functions - Özlem Akkoca, Arzu Tüzüner, Ceren Ersöz Ünlü, Gökçe Şimşek, Selda Kargın Kaytez, Gülay Aktar Uğurlu, 2020 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Aug 18]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0145561319881061 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Stewart MG, Witsell DL, Smith TL, Weaver EM, Yueh B, Hannley MT. Development and validation of the Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) scale. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(2):157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tiwari D, Surianarayanan G, Sundararajan V, Virtual KP. Follow-up T, for patients undergone Septoplasty Amid the COVID pandemic. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12070-020-01916-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrews PJ, Poirrier A-L, Lund VJ, Choi D. Outcomes in endoscopic sinus surgery: olfaction, nose scale and quality of life in a prospective cohort study. Clin Otolaryngol. 2016;41(6):798–803. doi: 10.1111/coa.12665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolger WE, Butzin CA, Parsons DS. Paranasal sinus bony anatomic variations and mucosal abnormalities: CT analysis for endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 1991;101(1 Pt 1):56–64. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199101000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resident, Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Okmeydanı Training and Research Hospital, Darulaceze Cad. No: 25 Posta Kodu: 34400 Okmeydanı, Sisli, Istanbul, Turke, Ahmed EA, Hanci D, Specialist, Okmeydanı Training and Reseacrh Hospital ENT Clinic, Sisli, Istanbul, Turkey, Üstün O, Resident, Okmeydanı Training and Reseacrh Hospital ENT Clinic, Sisli, Istanbul, Turkey, et al. Surgıcal Techniques for the Treatment of Concha Bullosa: A Systematic Review. Otolaryngol Open J. 2018 Aug 2;4(1):9–14.

- 13.Mehta R, Kaluskar SK. Endoscopic turbinoplasty of Concha Bullosa: long term results. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;65(Suppl 2):251–254. doi: 10.1007/s12070-011-0368-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatipoglu HG, Cetin MA, Yuksel E. Nasal septal deviation and concha bullosa coexistence: CT evaluation. B-ENT. 2008;4(4):227–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andaloro C, La Mantia I, Castro V, Grillo C. Comparison of nasal and olfactory functions between two surgical approaches for the treatment of concha bullosa: a randomised clinical trial. J Laryngol Otol. 2019;30:1–5. doi: 10.1017/S0022215119001968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koçak İ, Gökler O, Doğan R. Is it effective to use the crushing technique in all types of concha bullosa. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273(11):3775–3781. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-4097-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]