Abstract

Tuberculosis is a highly contagious granulomatous disease which is endemic in South East Asia. Most common presentation is pulmonary tuberculosis which is spread by droplets inhalation of mycobacterium tuberculosis bacterium. Nasopharyngeal tuberculosis is a rare entity which poses a diagnostic difficulty as its presentation is greatly similar to that of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Herein, we describe two cases of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis which mimics nasopharyngeal malignancy leading to diagnostic difficulties.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Nasopharyngeal tuberculosis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Introduction

The most common site of extrapulmonary tuberculosis includes lymph nodes, pleural and bone [1]. Upper respiratory tract remains one of the least common sites for tuberculosis. Rohwedder et al. reported that only 0.1% of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis has nasopharyngeal involvement [2]. Nasopharyngeal tuberculosis has a range of clinical presentation from being asymptomatic to neck swelling, loss of weight, night sweats and hearing loss. A study by Waldron et al. demonstrated that nasopharyngeal tuberculosis commonly occurs as primary infection with lymph nodes involvement without active pulmonary disease [3]. Patients with fungating and rapidly growing lesion of tuberculosis over the roof of nasopharynx may present with cranial nerve palsy should the growth invade the cavernous sinus. Similarly, nasopharyngeal carcinoma typically presents with a nasopharynx mass, neck swelling and hearing loss. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is prevalent in the Bidayuh and Chinese ethnicity in Malaysia. The identical presentations of both identities should alert the treating surgeon regarding the differential diagnosis of nasopharyngeal mass especially in a tuberculosis endemic region.

Case Report 1

A 23 years old gentleman presented with bilateral neck swelling for 6 months. It was gradually increasing in size but painless. It was associated with productive cough with whitish sputum, loss of appetite and loss of weight of 7 kg in 1 month. He denied any haemoptysis, fever, night sweats, tuberculosis contact, or family history of malignancy. He was an active smoker of 10 pack years. Upon examination, there was a right sided neck swelling over the right level III measuring 3 cm x 3 cm which was firm, non-tender, fixed, irregular, matted with normal overlying skin. There was a second swelling over left level II measuring 2 cm x 2 cm with the similar characteristics. On flexible nasopharyngoscopy, there was a nasopharyngeal reddish mass abutting bilateral posterior choanae and occluding bilateral Fossa of Rosenmuller and eustachian tube opening (Fig. 1). Lung examination showed decreased vocal resonance, dull on percussion and decreased air entry over the left lower zone. Based on the presentation of nasopharyngeal mass with neck and lung lesion, our provisional diagnosis was nasopharyngeal carcinoma with cervical nodal and lung metastasis. We proceeded with computed tomography of neck, thorax and abdomen which showed bilateral cervical supraclavicular lymphadenopathies and large lower lobe lung mass. Biopsies taken from the nasopharynx, cervical node and lung came back as chronic granulomatous inflammation with positive acid-fast bacilli consistent with tuberculosis. A final diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis with extrapulmonary spread to nasopharynx and cervical nodes was made. He was started on anti-tuberculosis drugs consisting of ethambutol, isoniazid, rifampicin and pyrazinamide immediately and upon last follow up, he was well with resolution of nasopharynx mass and cervical swelling.

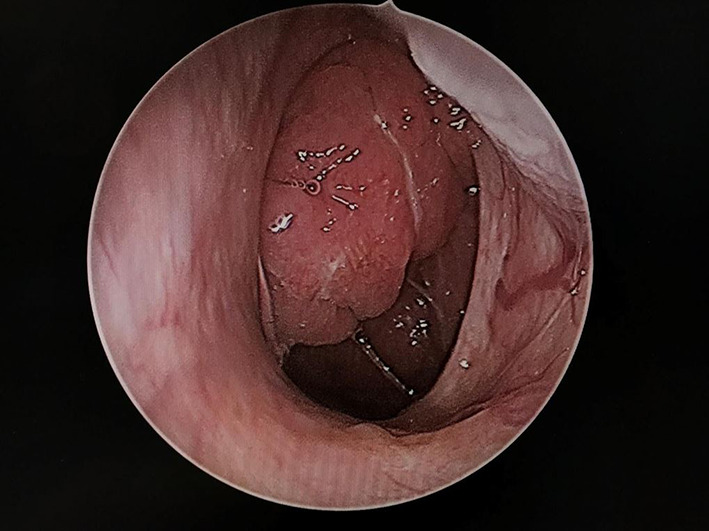

Fig. 1.

Endoscopic image of nasopharynx with an irregular mass extending up to posterior choanae

Case Report 2

A 42 years old gentleman presented with bilateral nasal blockage for six months with associated cacosmia and anosmia. Patient had loss of weight of 5 kg within 6 months duration. Otherwise no other nasal symptoms and no symptoms suggestive of tuberculosis. General and systemic examination were unremarkable. Rigid nasal endoscopy findings revealed reddish mass at nasopharynx with glandular posterior pharyngeal wall (Fig. 2). Examination of the larynx was normal. Histopathology report from the nasopharyngeal mass biopsy sent revealed caseating granuloma with Langhans giant cells and acid-fast bacilli. Mantoux test was positive (25 mm). Routine blood investigations sent were normal. Sputum sent for acid fast bacilli were negative for all samples. He was started on anti-tuberculosis regime and his subsequent follow up showed gradual resolution of nasopharyngeal mass.

Fig. 2.

Endoscopic image of the nasopharynx with an ill-defined mass over the right Fossa of Rosenmuller

Discussion

Tuberculosis is commonly caused by mycobacterium tuberculosis. Easily spread via inhalation of air droplets, tuberculosis is common in areas of overpopulated unvaccinated communities with poor hygiene. In developing countries, poor sanitation, malnutrition, and overcrowding has propagated the rise of tuberculosis [4]. Low socioeconomic status and smoking are also known risk factors. Pulmonary tuberculosis presents with prolonged cough, hemoptysis and loss of weight. Although pulmonary tuberculosis is the most encountered, extrapulmonary tuberculosis may occur even in healthy individuals.

In Othorhinolarygology setting, the most common presentation of extrapulmonary tuberculosis is tuberculosis lymphadenitis of the cervical nodes. A clinical analysis done by Sririmpotong et al. revealed majority of cervical lymphadenopathy secondary to tuberculosis were located in the upper and middle cervical levels [5]. Patient may also present with nasal discharge, nasal obstruction and epistaxis. A review of literature showed a range of uncommon presentations. Bath et al. has reported otological symptoms of otalgia and hearing loss as the only presentation of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis [6]. Interestingly, Aktan et al. has reported snoring as the only symptom [7]. Therefore, a through otorhinology and head and neck examination are crucial to prevent misdiagnosis. Nasopharyngeal mass has a differential diagnosis of enlarged adenoids, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, lymphoma or Castleman’s disease. It has been postulated that nasopharyngeal tuberculosis may be due to reactivation of mycobacterium tuberculosis in the adenoids during episodes of immunosuppression or via droplet inhalation of airborne acid-fast bacilli [8]. Ennouri et al. reported two possible routes of infection. The first being inhalation via airway or canalized bacillary expectoration. The second mode is via lymphatic or hematogenous spread from pulmonary tuberculosis [9]. With the huge prevalence rate of nasopharyngeal carcinoma and its immensely similar clinical symptoms with nasopharyngeal tuberculosis, it is not uncommon to misdiagnose. Furthermore, nasopharyngeal tuberculosis may only present with minor nasal symptoms as seen in the second case without pulmonary manifestation. With this case report, we hope to highlight nasopharyngeal tuberculosis as a provisional diagnosis in patients with nasopharyngeal mass and highly recommend tuberculosis screening in the investigations notably in high risk patients who are exposed to tuberculosis. Tuberculosis screening should include a blood investigation of erythrocyte sedimentation rate, sputum samples for acid fast bacteria, chest radiography and Mantoux testing.

The gold standard for diagnosis is a biopsy from the nasopharynx. Histopathology shows granulomatous inflammation with caseous necrosis and giant cells with acid fast bacilli. It is not uncommon for biopsy to be negative of tuberculosis initially. Percodani et al. suggested for multiple repeat biopsies should there be a high index of suspicion to obtain diagnosis. He also recommended deep biopsy under general anaesthesia to increase accuracy of biopsy [10]. Imaging is not compulsory in making a diagnosis. However, we recommend magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the neck should there be a diagnosis dilemma. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma presents with soft tissue invasion and bony erosion especially base of skull in advanced cases whereas a nasopharyngeal tuberculosis may show a polypoidal mass or mucosa thickening. Sithinamsuwan et al. presented a case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis with abducens nerve palsy due to it’s invasion into cavernous sinus [11]. As per the first case whereby the presentation was indistinguishable from a nasopharyngeal carcinoma with cervical and lung metastasis, we recommend obtaining a fine needle aspiration cytology of neck and an ultrasound guided biopsy of lung lesion for confirmation of diagnosis and to rule out malignancy. In a nutshell, we advocate nasopharyngeal biopsy and tuberculosis screening notably in patients who stay in or travel to tuberculosis endemic regions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for the permission to publish this paper.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.PHE. Tuberculosis in the UK: 2012 report. Public Health England, 2012 (accessed 5 November 2013). http://www.hpa.org.uk/webw/ HPAweb&HPAwebStandard/HPAweb_C/1317134916916.

- 2.Rohwedder JJ. Upper respiratory tract tuberculosis: sixteen cases in a general hospital. Ann Intern Med. 1974;80(6):708–713. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-80-6-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waldron J, Van Hasselt CA, Skinner DW, Arnold M. Tuberculosis of the nasopharynx: clinicopathological features. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1992;17(1):57–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1992.tb00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossi-Espagnet A, Goldstein GB, Tabibzadeh I. Urbanization and health in developing countries: a challenge for health for all. World Health Stat Q. 1991;44(4):186–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srirompotong S, Yimtae K, Jintakanon D. Nasopharyngeal tuberculosis: manifestations between 1991 and 2000. Otolaryngol—Head Neck Surg. 2004;131(5):762–4. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bath AP, O'Flynn P, Gibbin KP. Nasopharyngeal tuberculosis. J Laryngol Otol. 1992;106(12):1079–1080. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100121802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aktan B, SelimoĞlu E, Üçüncü H, Sütbeyaz Y. Primary nasopharyngeal tuberculosis in a patient with the complaint of snoring. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116(4):301–303. doi: 10.1258/0022215021910609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gnanapragasam A. Primary tuberculosis of the naso-pharynx. Med J Malaya. 1972;26:194–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ennouri A, Maamouri M, Bouzouaïa N, Hajri H, Bouzouita K, Ferjani M, Marrakchi H. Tuberculosis of the upper digestive and respiratory tract. Revue de Laryngologie- Otologie-Rhinologie. 1990;111(3):217–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Percodani J, Braun F, Arrue P, Yardeni E, Murris-Espin M, Serrano E, Pessey JJ. Nasopharyngeal tuberculosis. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113(10):928–931. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100145621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sithinamsuwan P, Sakulsaengprapha A, Chinvarun Y. Nasopharyngeal tuberculosis: a case report presenting with diplopia. J med Assoc thai. 2005;88(10):1442–1446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]