Abstract

To study the various computed tomography (CT) cisternogram findings in idiopathic cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks and the long term treatment modalities after surgical repair of idiopathic CSF leaks. This was a descriptive study conducted among 25 patients in MCV memorial ENT trust hospital, Pollachi between May 2014 and May 2020 amongst patients who underwent CT cisternogram for unilateral or bilateral spontaneous rhinorrhea with or without associated headache, visual disturbances and papilloedema diagnosed to be idiopathic CSF leak by investigations. These patients then underwent CSF leak repair and postoperatively were managed with weight reduction, low salt diet and diuretic therapy. Post surgery these patients were followed up for a period of 12 months and were evaluated on the basis of presence or absence of headache, rhinorrhea and papilloedema at the end of 1st month, 3rd month, 6th month and 1 year and data was collected. CT cisternogram findings were evaluated by proportion method and evaluation of long term management was done using proportion and repeated measures ANOVA for all patients. Evidence of the presence of previously mentioned CT cisternogram or contrast MRI findings at the end of 1 year of post-surgical treatment was recorded where patients were willing for the same. CT Cisternography was done for all patients and 72% patients had empty sella appearance while 28% had partially empty sella. Other findings included perioptic filling, optic blunting and arachnoid pits which were found in 11(44%), 8(32%) and 12(48%) of patients respectively. Only 3(12%) out of 25 patients had an encephalocoele. The commonest site of leak in CT cisternography was the cribriform plate (52%) followed by lateral recess of sphenoid (48%). None of the patients had multiple sites of leak in CT cisternography. On follow up post surgery maximum resolution of symptoms was found at the end of 12 months where 23 out of 25 patients improved. In our study, out of 25 only 5 patients agreed to undergo post diuretic therapy MRI scan out of which 2 patients had partially empty sella and 3 had normal sella indicating resolution of BIH. CT cisternography is an important investigation which aids in the diagnosis of CSF rhinorrhea due to idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH). The medical management of IIH post surgery such as weight reduction, salt restriction and diuretic therapy is also crucial to prevent recurrence of symptoms.

Keywords: Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea, Spontaneous, Idiopathic intracranial hypertension, Computed tomography

Introduction

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is the end product of ultrafiltration of plasma across the epithelial cells in the choroid plexus lining the ventricles of the brain. A basal layer Na+/K+ ATPase is responsible for actively transporting Na+ into epithelial cells, after which water follows across this gradient. Carbonic anhydrase catalyzes the formation of bicarbonate inside the epithelium cell. Another Na+/K+ ATPase lining the ventricular side of the epithelium extrudes Na+ into the ventricle, with water following across this ionic gradient. The resulting fluid is termed cerebrospinal fluid.

CSF rhinorrhea is the leakage of CSF from the subarachnoid space into the nasal cavity due to a defect in the dura, bone and mucosa. The origin of the fluid may be from the anterior, middle or posterior cranial fossa, either via the frontal, ethmoid or sphenoid sinuses or from the cribriform plate. Increased CSF pressure exerted on areas of the anterior skull base such as the lateral lamella of the cribriform or lateral recess of the sphenoid sinus results in bone remodeling and thinning. Ultimately, a defect is formed. At this point, the dura herniates through the defect forming a meningocoele or meningoencephalocoele if it involves brain tissue in addition to dura.

Ommaya et al. classified CSF leaks aetiologically into traumatic and non-traumatic types [1], idiopathic CSF leaks are non traumatic type related to an increase in intracranial pressure (ICP) associated with benign intracranial hypertension (BIH) seen in middle aged obese women demographically [2]. Patients present with history of clear, watery discharge from the nose usually unilateral. Presence of headache and visual disturbances suggests increased intracranial pressure. Papilloedema is found in many cases of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) who present with vision disturbances.

The most commonly used laboratory test is beta2-transferrin test to distinguish CSF from other causes of rhinorrhea. It is a reliable test to diagnose active CSF leak. But in cases of traumatic leaks, where orbit injury is suspected it may show false positive as vitreous humor also contains the same protein. Computed tomography (CT) cisternogram is a radiological investigation for diagnosing the site of CSF leak which is performed after administration of an intrathecal dye prior to the scan. After injecting contrast, the patient is placed in trendelenburg position to opacify the basal cisterns followed by CT images. There are specific findings in CT cisternogram in spontaneous CSF leaks associated with IIH which can aid in diagnosis. Intrathecal fluorescein dye followed by a thorough endoscopic examination is another modality for diagnosis.

Post-surgery, the treatment is on long term basis and depends mainly on medical management to reduce the ICP thereby reducing the BIH in idiopathic CSF leaks. Medical management can be done by weight reduction and diuretics. Decreasing the calorie intake and sodium intake is an effective measure to decrease weight. Diuretics like acetazolamide, furosemide and spironolactone are used to control the postoperative recurrence of idiopathic CSF leaks. Monitoring of serum electrolytes should be performed when diuretics are used.

In this study we plan to elucidate the CT cisternogram findings and emphasize on various long term management options including medical management with different diuretics.

Methodology

The aim of the study was to describe the various CT cisternogram findings in idiopathic CSF leaks and the long term treatment modalities after surgical repair of idiopathic CSF leaks. This was an observational study conducted in MCV memorial ENT trust hospital, Pollachi between May 2014 and May 2020 amongst patients with unilateral or bilateral spontaneous rhinorrhea with or without associated headache, visual disturbances and papilloedema diagnosed to be idiopathic CSF leaks by investigations. After detailed history and investigations those CSF leaks which were associated with trauma, skull base fractures, previous endonasal surgery, neoplasms invading the skull base, intracranial pathologies causing hydrocephalus and erosive lesions like mucocoele, fungal sinusitis etc. were excluded from the study. A total of 25 patients were included in the study after detailed evaluation with nasal endoscopy, fundoscopy for ascertaining presence or absence of papilloedema and CT cisternography. CT scans were acquired using a protocol of less than 1.5-mm slice thickness. The CT cisternography images were evaluated for the presence of:

-

o

Empty sella turcica

-

p

Partially empty sella turcica

-

q

Meningocoele

-

r

Dural ectasia

-

s

Optic nerve sheath abnormalities

-

t

Perioptic filling

-

u

Dilated Meckel’s cave

-

v

Arachnoid pits

The diagnosed cases of idiopathic CSF leak were then the taken up for surgical repair after counselling and obtaining informed consent. Post surgery these patients were started on diuretics such as 20% mannitol 100 ml intravenous t.i.d (not for long term treatment), Tab. acetazolamide 500 mg b.i.d, Tab furosemide 40 mg, o.d/b.i.d or Tab spironolactone 50 mg, o.d. The patients received laxatives and cough suppressants when indicated. Nasal pack was removed on the seventh postoperative day. All patients received postoperative broad-spectrum antibiotics for a period of 1 week. Patients were also started on low salt diet and were advised to decreased weight which would aid in the treatment. These patients were followed up for a period of 12 months and were evaluated at the end of 1st month, 3rd month, 6th month and 1 year and data was collected. Patients were evaluated on the basis of presence or absence of headache, rhinorrhea, papilloedema & evidence of the presence of previously mentioned CT cisternogram or contrast MRI findings at the end of 1 year of post surgical treatment where patients were willing for the same. CT cisternogram findings were evaluated by proportion method and evaluation of long term management was done using proportion and repeated measures ANOVA for all patients.

Results

Our study included 25 patients with diagnosed idiopathic CSF leak. Amongst this there were 18 females (72%) and 7 males (28%). The mean age of females was 46.05 years and that of the males was 45.4 years respectively. Rhinorrhea with or without headache was the commonest presenting symptom and all the patients had an active leak at the time of presentation (Table 1). “Teapot sign” was found to be positive where patient was made to lie down in prone position and active CSF leak was noticed from the nose.

Table 1.

Symptoms in patients with idiopathic CSF leak

| Symptons | Number of patients | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Rhinorrhoea | 25 | 100 |

| Headache + Rhinorrhoea | 22 | 88 |

| Vision disturbances | 0 | 0 |

CT Cisternography was done for all patients and 72% patients had empty sella appearance while 28% had partially empty sella. Other findings included perioptic filling, optic blunting and arachnoid pits which were found in 11(44%), 8(32%) and 12(48%) of patients respectively. Only 3(12%) out of 25 patients had an encephalocoele (Table 2). The commonest site of leak in CT cisternography was the cribriform plate in 13 patients (52%) followed by lateral recess of sphenoid in 12 patients (48%). None of the patients had multiple sites of leak in CT cisternography.

Table 2.

Computed tomography cisternography findings in patients with idiopathic CSF leak

| CT cisternogram findings | Number of patients | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Empty sella | 18 | 72 |

| Partially empty sella | 7 | 28 |

| Perioptic filling | 11 | 44 |

| Optic blunting | 8 | 32 |

| Arachnoid pits | 12 | 48 |

| Encephalocoele | 3 | 12 |

Post-surgical repair patients were started on diuretics which were acetazolamide & furosemide. The overall response irrespective of the drugs used in the 1st, 3rd, 6th and 12th month was observed. We compared the improvement of patients of the overall response to diuretic therapy using repeated measures ANOVA. The mean square was 39.788 and F value was found to be 149.765, p-value was < 0.0001 which was considered significant. Maximum resolution of symptoms was found at the end of 12 months where 23 out of 25 patients improved. During the course of postoperative management with diuretics symptoms such as muscle cramps and increased thirst were reported by some patients during the 1st month of follow up. Malaise and light headedness were the less common side effects. None of the patients complained of tinnitus which is occasionally found with diuretic therapy.

In our study, out of 25 only 5 patients agreed to undergo post diuretic therapy MRI scan out of which 2 patients had partially empty sella and 3 had normal sella indicating resolution of BIH.

Discussion

CSF rhinorrhea was first reported in the seventeenth century [3]. Both Wigand and Stankiewicz described closure of incidental CSF leaks during endoscopic sinus surgery. The presence of active CSF rhinorrhea requires a disruption of the barriers that normally separate the contents of the subarachnoid space from the nose and paranasal sinuses; that is, the leak incorporates defects of the arachnoid and dura mater, mucosa, and the intervening bone. Furthermore, a pressure gradient is also required for idiopathic CSF rhinorrhea.

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension may be attributed to the following factors:

Parenchymal edema

Increased cerebral blood volume

Excessive CSF production

Compromised CSF resorption

Venous outflow obstruction

The pathophysiology of the disease is currently unknown. One common theory behind the association of obesity and elevated ICP is that excess weight in the central compartment of the body leads to high intra-abdominal pressures. An increase in intra-abdominal pressure raises ICP by decreasing cerebral venous return to the heart. This obstructs cerebral venous outflow, thereby raising cerebral blood volume and increasing ICP by preventing normal CSF absorption. The association of obesity with BIH has been reported in many studies [4–6]. Radhakrishnan et al. calculated an increase in incidence to 21.4 per 100,000 for obese females with a BMI of 30 kg/m2, 10- to 20- fold of the incidence in the total population [7].

Patients usually present with unilateral, clear, watery discharge from the nose associated with headache. In our study headache with rhinorrhea was found in 22 (88%) out of 25 patients. Rush JA et al. found 75% of patients presenting with headache in a study conducted among 64 patients [8]. A gush of fluid on forward tilting of the head, classically known as “teapot sign” is characteristic of CSF leak [9].The headache attributed to idiopathic intracranial hypertension is when the headache develops in close temporal relation to the increased intracranial pressure and improves after resolution of CSF pressure. The headache should be progressive with at least two of the following according to International Headache Society’s classification (ICHD-3) of idiopathic intracranial hypertension [10].

Daily occurrence

Diffuse and/or constant non-pulsating pain

Aggravated by coughing or straining

Wall M et al. found monocular or binocular transitory visual obscurations (TVO) ranging from blurring to total loss of light perception in up to 72% of the patients [11]. However none of the patients in our study had visual symptoms or papilloedema on fundus examination. Papilloedema is the cardinal sign of IIH. Optic disc edema is the cause of visual loss of IIH. The higher the grade of the papilloedema, the worse the visual loss. Pulsatile bruit-like tinnitus, either unilateral or bilateral, exists in 8–60% of patients [12]. It is reversible and usually resolves whenever CSF pressure normalizes. None of the patients in our study had pulsatile bruit-like tinnitus which was seen in patients in studies conducted by Bulens C et al. Weisberg et al. and Round R et al. [13–15].

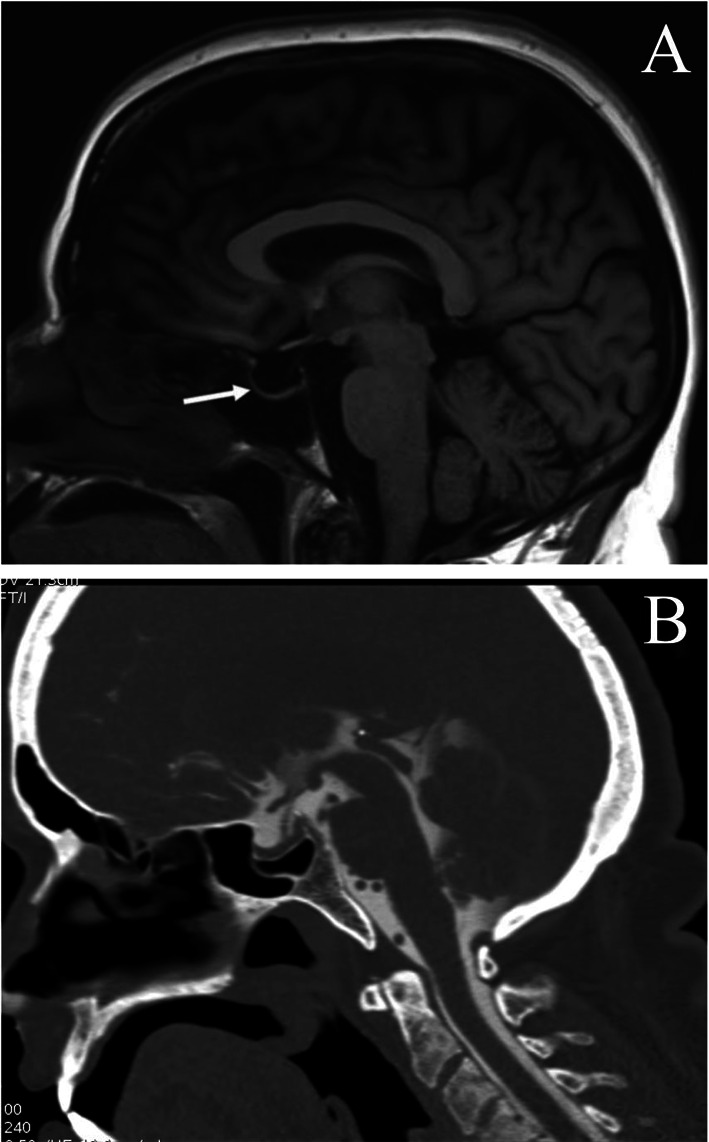

Patients with spontaneous idiopathic CSF leaks have some characteristics findings on CT scan that may aid in their diagnosis. The term empty sella refers to a condition in which the sella turcica is filled mainly with CSF. Pulsatile forces resulting from this increased ICP seek the path of least resistance. One of the sites of inherent structural weakness is the fascia of the sellar diaphragm. Herniation of meninges and CSF through the sellar diaphragm results in the appearance of an empty sella on imaging [16]. Amongst our patients majority had empty sellae (72%) and 7 out of 25 patients (28%) had partially empty sellae (Fig. 1). Shetty et al. reviewed 11 patients with spontaneous sphenoid CSF leaks and noted that 63% had completely empty sellae and an additional 27% had partially empty sellae [17]. Scholsser et al. conducted a study and found it to be 67% and 33% respectively [18]. Approximately 80% of patients with empty sella have obstruction to normal CSF absorption at the arachnoid villi [16]. Brodsky MC et al. conducted a study in 20 patients of peudotumour cerebi with IIH and found 70% patients having empty sella which corroborates with our study [19]. A strong statistical correlation between an empty sella and idiopathic intracranial hypertension has been well established. Zagardo MT et al. suggested that an empty sella may serve as a radiologic indicator of elevated ICP, as reversal of an empty sella has been noted in cases of intracranial hypertension following successful treatment of increased ICP [20].

Fig. 1.

a CT image showing empty sella (white arrow), b CT image showing partially empty sella

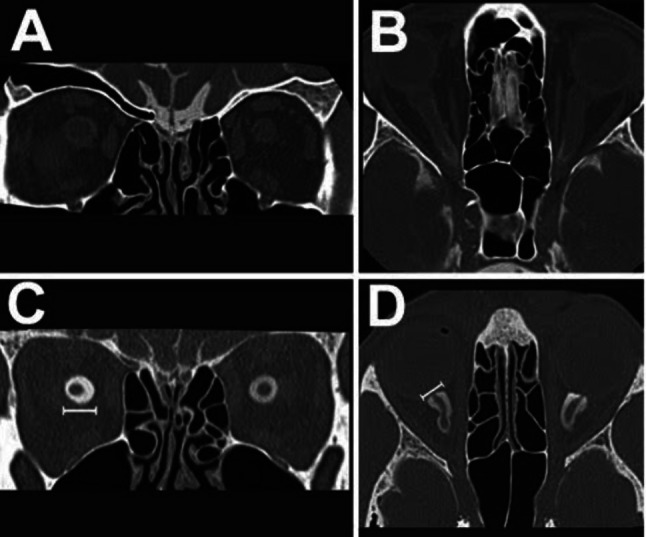

Due to the increased ICP, the skull base of patients with spontaneous idiopathic CSF leaks is often broadly thinned and attenuated [18]. Arachnoid pits are due to bony impressions from arachnoid villi and are usually identified along the bony skull base in 63% of patients with spontaneous idiopathic CSF leak [17]. In our study arachnoid pits were found in 12(48%) patients. B.Schuknecht et al. also reported arachnoid pits in their study of 27 patients [21]. Mahati et al. also noted that sustained increased pressure can also lead to the formation of prominent arachnoid pits at the skull base with areas of overlying dural thinning, as well as the formation of meningoceles and meningoencephaloceles [22]. Only 3(12%) out of 25 patients in our study had encephalocoele. Other findings include optic nerve sheath enlargement and/or tortuosity, optic nerve head protrusion with flattening of the posterior globe, and optic nerve head edema with enhancement (Fig. 2). In our study perioptic filling were found in 11(44%) out 25 patients. Skull base findings include scalloping of the inner table of the calvarium, prominent arachnoid pits, multiple osseous defects along the skull base, and enlargement of the skull base foramina [23]. The most common sites for CSF leak in patients with spontaneous idiopathic CSF leak are the lateral recess of the sphenoid sinus and the ethmoid roof or cribriform plate. Shetty et al. evaluated the degree of sphenoid pneumatization in 11 patients with spontaneous sphenoid CSF leaks. He found 10(91%) of 11 patients had significant pneumatization of the lateral recesses in comparison with 23% of normal controls [17]. In our study the site of CSF leak was found to be cribriform plate or roof of ethmoid in 13(52%) patients while 12(48%) had leak from lateral recess of sphenoid. Schlosser et al. conducted a study in 28 patients in 2003 and found 42% having leak from sphenoid sinus which corroborates with our study. They found 21.4% having leak from cribriform plate and 17% having multiple skull base defects [24]. However there were no patients with multiple skull base defects in our study.

Fig. 2.

a, c, d CT image showing perioptic filling, b CT image showing optic nerve tortuosity

Endoscopic endonasal repair of skull base defects has widely replaced open repair via a craniotomy and has overall success rates of 90% with minimal morbidity [25]. All our patients underwent endoscopic endonasal repair of CSF leak using the same surgical technique and by the same surgeon. After surgical repair, weight loss and diuretic therapy is necessary to control and decrease the symptoms and also to prevent further recurrences. Long term follow up is necessary to validate the effectiveness in the control of idiopathic CSF leaks.

In 1974, Newborg reported remission of symptoms of IIH in all nine patients placed on a low-calorie adaptation of Kempner’s rice diet [26]. Kempner’s rice diet included 400 to 1000 cal per day consisting of fruits, rice, vegetables, and occasionally 1 to 2 oz of meat. Fluids were limited to 750 to 1250 mL/d and sodium to less than 100 mg/d. In addition to lifestyle modifications for weight loss, monotherapy or combination therapy with diuretics plays a crucial role in the management of IIH. The carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, acetazolamide, is usually the first-line drug in treatment and acts by reducing the CSF production and thus ICP. An initial dose of 250 mg twice a day gradually increasing to a daily dose of 1000–1250 mg has been recommended. Side-effects commonly include malaise, paraesthesias, altered taste sensation, fatigue, gastric upset. When acetazolamide is insufficient or intolerable, furosemide (40–120 mg/day) combined with potassium sparing diuretic like spironolactone should be considered [27]. Although the effect of furosemide has never been evaluated in IIH patients, it seems to be much less potent than acetazolamide [28]. Michael Wall et al. started furosemide at a dose of 20 mg orally twice daily and gradually increased the dose to a maximum of 40 mg orally twice daily [29]. Potassium supplementation was given as needed as hypokalemia occurred in a few subjects. McCarthy and Reed assumed that the effects of acetazolamide and furosemide might be additive [30]. Schoeman et al. treated pediatric IIH patients with this combination therapy and found it to be effective than single drug therapy [31]. In a study conducted by M. Usman Khan et al. they found that spironolactone decreases the symptoms of IIH by blocking aldosterone receptors [32]. Topiramate, a relative new anticonvulsant, also inhibits carbonic anhydrase at clinically relevant doses [33]. Symptomatic headache is treated with analgesics such as paracetamol as well as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, but should be prescribed with precaution due to the risk of medication overuse headache.

In a study conducted by Sorensen et al. they reported the cessation of symptoms in 70% of IIH patients within 3 months of medical treatment [34]. Johnston and Paterson in their study described a recovery from headache after diuretic therapy in 78% after 2 months [12]. After 6 months of therapy, 21(84%) out of 25 patients were relieved of the symptoms and 23(92%) were improved after 12 months of therapy. In our study we did the repeated measures ANOVA for all patients on diuretic therapy. This was found to be statistically significant (P value < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Idiopathic CSF leaks are predominantly seen in middle aged obese females and may sometimes be difficult to diagnose. The specific findings in CT cisternography of patients with spontaneous CSF leak associated with IIH is a good diagnostic aid both for the site of leak as well as for confirmation of aetiology although it has the disadvantage of being an invasive procedure. There is no best treatment strategy for the control of IIH which lead to idiopathic CSF leaks, as the recent NORDIC and Cochrane studies of 2014 & 2015 show respectively but, diuretic therapy is the mainstay for the control of symptoms thereby giving us a better approach for long term management of idiopathic CSF leaks.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contribution to this paper and all the authors have approved the version to be published.

Funding

No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Availability of Data and Material

Data transparency has been maintained.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the institution ethics committee.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

The participants have consented to the submission of the case details for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ommaya AK, Di Chiro, et al. Hydrocephalus and leaks. In: Wager H, et al., editors. Principles of nuclear medicine. 2. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woodworth BA, Schlosser RJ. Cerebrospinal fluid leak and encephaloceleCerebrospinal fluid leak and encephalocele. In: Kennedy DW, Hwang PH, editors. Rhinology diseases of the nose, sinuses, and skull base. 1. USA: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2012. p. 591. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aarabi B, Leibrock LG. Neurosurgical approaches to cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea. Ear Nose Throat J. 1992;71:300–305. doi: 10.1177/014556139207100704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugerman HJ, DeMaria EJ, Felton WL, 3rd, Nakatsuka M, Sismanis A. Increased intra-abdominal pressure and cardiac filling pressures in obesity-associated pseudotumor cerebri. Neurology. 1997;49:507–511. doi: 10.1212/WNL.49.2.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugerman HJ, Felton WL, 3rd, Salvant JB, Jr, Sismanis A, Kellum JM. Effects of surgically induced weight loss on idiopathic intracranial hypertension in morbid obesity. Neurology. 1995;45:1655–1659. doi: 10.1212/WNL.45.9.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloomfield GL, Ridings PC, Blocher CR, Marmarou A, Sugerman HJ. A proposed relationship between increased intra-abdominal, intrathoracic, and intracranial pressure. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:496–503. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199703000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radhakrishnan K, Thacker AK, Bohlaga NH, Maloo JC, Gerryo SE. Epidemiology of idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a propective and case-control study. J Neurol Sci. 1993;116(1):18–28. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(93)90084-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rush JA. Pseudotumor cerebri: clinical profile and visual outcome in 63 patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980;55:541–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luotonen J, Jokinen K, Laitinen J. Localisation of a CSF fistula by metrizamide CT cisternography. J Laryngol Otol. 1986;100(8):955–958. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100100398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition (beta version) Cephalalgia. 2013;33(9):629–808. doi: 10.1177/0333102413485658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wall M, Ceorge D. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. A prospective study of 50 patients. Brain. 1991;114:155–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnston I, Paterson A. Benign intracranial hypertension II. CSF pressure and circulation. Brain. 1974;97:301–312. doi: 10.1093/brain/97.1.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bulens C, De Vries WA, Van Crevel H. Benign intracranial hypertension. A retrospective and follow-up study. J Neurol Sci. 1979;40:147–157. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(79)90200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weisberg LA. Benign intracranial hypertension. Medicine (Baltimore) 1975;54:197–207. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197505000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Round R, Keane JR. The minor symptoms of increased intracranial pressure: 101 patients with benign intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 1988;38(9):1461. doi: 10.1212/WNL.38.9.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brismar K, Bergstrand G. CSF circulation in subjects with the empty sella syndrome. Neuroradiology. 1981;21:167–175. doi: 10.1007/BF00367338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shetty PG, Shroff MM, Fatterpekar GM, et al. A retrospective analysis of spontaneous sphenoid sinus fistula: MR and CT findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21(2):337–342. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schlosser RJ, Bolger WE. Significance of empty sella in cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128(1):32–38. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2003.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brodsky MC, Vaphiades M. Magnetic resonance imaging in pseudotumor cerebri. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(9):1686–1693. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)99039-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zagardo MT, Cail WS, Kelman SE, Rothman MI. Reversible empty sella syndrome in idiopathic intracranial hypertension: an indicator of successful therapy? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1981;21:167–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuknecht B, Simmen D, Briner HR, Hozmann D. Nontraumatic skull base defects with spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea and arachnoid herniation: imaging findings and correlation with endoscopic sinus surgery in 27 patients. Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29(3):542–549. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahati Reddy MD, Kristen Baugnon MD. Imaging of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea and otorrhea. Radiol Clin. 2017;55(1):167–187. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bidot S, Saindane AM, Peragallo JH, et al. Brain imaging in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neuroophthalmol. 2015;35(4):400–411. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schlosser RJ, Bolger WE. Nasal cerebrospinal fluid leaks: critical review and surgical considerations. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:255–265. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200402000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papay FA, Maggiano H, Daminquez S, et al. Rigid endoscopic repair of paranasal sinus cerebrospinal fluid fistulas. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:1195–1201. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198911000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newborg B. Pseudotumor cerebri treated by rice reduction diet. Arch Intern Med. 1974;133:802–807. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1974.00320170084007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skau M, Brennum J, Gjerris F, Jensen R. What is new about idiopathic intracranial hypertension? An updated review of mechanism and treatment. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:384–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buhrley LE, Reed DJ. The effect of furosemide on sodium-22 uptake into cerebrospinal fluid and brain. Exp Brain Res. 1972;14(5):503–510. doi: 10.1007/BF00236592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michael Wall MD. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri) Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2008;8:87–93. doi: 10.1007/s11910-008-0015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCarthy KD, Reed DJ. The effect of acetazolamide and furosemide on CSF production and choroid plexus carbonic anhydrase activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1974;189:194–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schoeman JF. Childhood pseudotumor cerebri: clinical and intracranial pressure response to acetazolamide and furosemide treatment in a case series. J Child Neurol. 1994;9(2):130–134. doi: 10.1177/088307389400900205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Usman Khan M, Khalid H, Salpietro V, Weber KT. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension associated with either primary or secondary aldosteronism. Am J Med Sci. 2013;346(30):194–198. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31826e3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dodgson SJ, Shank RP, Maryanoff BE. Topiramate as an inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes. Epilepsia. 2000;41(s5):S35–S39. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb06047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sorensen PS, Krogsaa B, Gjerris F. Clinical course and prognosis of pseudotumor cerebri. A prospective study of 24 patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 1988;77(2):164–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1988.tb05888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data transparency has been maintained.