Abstract

Eagle’s Syndrome is a much discussed yet controversial and debatable diagnosis of exclusion which is treated by many specialities with often unsatisfactory results. Due to entrapment/impingement on surrounding neurovascular structures by elongated styloid process patient may present with multitude of symptoms. Treatment is controversial and opinions are divided on choice of conservative and surgical management. Aim was to study outcomes of conservative and surgical modalities of treatment of Eagle’s Syndrome and bring some clarity on management, what to offer, to whom and when. This prospective observational descriptive study included 15 patients of Eagle’s Syndrome, 7 were treated with conservative method and 8 underwent resection of styloid process with intraoral approach. With objectives in mind to study efficacy of both management modalities, pain visual analogue scale (VAS) scores were recorded pre-intervention, post-intervention and during follow up on 1, 3 and 6 months and compared. Conservative management resulted in up to 70% reduction in pain VAS scores till 3 months of therapy (mean pre-intervention score being 3.71, 3 months—1, 6 months—1.29), while surgical modality resulted in nearly 99% reduction in mean pain VAS scores up to 3 months and even improved after 6 months (mean pre-intervention score being 6.75, 3 months–0.5, 6 months–0.13). With this we can conclude that conservative management provide satisfactory short-term (up to 3 months) results but recurrences are known, while surgical resection of elongated styloid process gives better long-term results (6 months and beyond).

Keywords: Eagle’s syndrome, Stylalgia, Elongated styloid process, Resection of styloid process

Introduction

Eagle’s syndrome also known as Stylalgia or Stylohyoid syndrome consists of myriad of symptoms occurring due to elongated/ abnormally angulated styloid process or calcified stylohyoid ligament entrapping one or many neuro-vascular components of stylohyoid complex present within maxillo-vertebro-pharyngeal space [1]. Symptoms which result are due to entrapment/impingement on cranial nerves like hypoglossal, glossopharyngeal, vagus or branches of trigeminal and sometimes carotid vessels. Common presentation is persistent pain in throat radiating to ipsilateral hemiface, ipsilateral referred otalgia, pharyngeal foreign body sensation, odynophagia, dysphagia, or cervicofacial pain [1]. This pain is known to get exacerbated or triggered with rotation of head, tongue movements, deglutition, or mastication. Classically described by Watt W. Eagle in 1937, exacerbation of pain/tenderness and/or palpable bony prominence during palpation of ipsilateral tonsillar fossa in a symptomatic patient should indicate toward possibility of Eagle’s syndrome [2]. Diagnosis can be confirmed with help of Orthopantomogram (OPG) or Non-Contrast Computed Tomography (NCCT) scan of face and neck, which enable clinician to measure elongated styloid process or observe calcification of stylohyoid ligament. Treatment options available are (a) conservative, with oral steroids, carbamazepine, and/or local anaesthetic blocks, and (b) surgical excision of styloid process, which is generally more preferred. Surgery can be performed via intraoral or extra-oral approach, each having its own merits and demerits.

Described more than a century ago, this condition remains an enigma and patients are usually found being cross-referred from outpatient departments of neurology, dentistry, surgery and otorhinolaryngology. With myriad of literature present advocating different modalities of treatment, clinicians need to be very much aware about its plethoric presentation as well as management modalities, so that patients can be counselled and offered appropriate, adequate, and holistic treatment. Aim of this study is to observe different presentations of Eagle’s Syndrome and discuss various modalities of treatment, their success rate, and in turn, find some clarity of what management to offer, to whom and when.

Materials and Methods

After taking approval from Institutional ethics committee, this prospective observational descriptive study was conducted over a period of 30 months between June 2017 to December 2019 in two tertiary care centres in West Bengal and Madhya Pradesh, India. 20 patients who presented or got referred to Department of Otorhinolaryngology with various symptoms, worked up and eventually diagnosed with Eagle’s Syndrome were included in this study as per its inclusion and exclusion criteria. Informed consents were taken, and patients were made free to choose the modality of treatment, change it during study, and to exit from it as and when they wish so. Five patients were excluded from study due to either loss of follow up or their refusal for further treatment. All patients were counselled regarding nature of their ailment, treatment choices available, their success rate as per current literature and follow up duration of 6 months. They were offered treatment, either conservative or surgical, as per their choice.

With objectives to observe and study different presentations of Eagle’s Syndrome and efficacy of both conservative and surgical modality of management in terms of subjective assessment of pain on visual analogue scale (VAS, a 10 point scoring system, evaluated as 0 = no pain and 10 = maximum pain, measured pre and post intervention and 1, 3 and 6 months thereafter), we included adult patients diagnosed with Eagle’s Syndrome and excluded those who were suffering from malignancies, bleeding diathesis or seizure disorders.

Most of the patients presented with pharyngeal pain with hemifacial radiation, referred otalgia, odynophagia and pharyngeal foreign body sensation. Few reported exacerbations of symptoms on neck movement, swallowing or mastication. All cases were subjected to complete head and neck examination which revealed common findings of either tenderness on digital palpation over tonsillar fossa (which, in few cases precipitated/exaggerated symptoms) or palpable styloid process. One case presented with giddiness and blackouts on turning head to left in addition to odynophagia. While otoneurological tests negated any evidence of peripheral vestibulopathies, oropharyngeal examination revealed palpable styloid process over left tonsillar fossa. A CT Angiogram was also performed which ruled out Carotid Artery Syndrome. All patients, including this case, were subjected to NCCT scan of face and neck with three-dimensional reconstruction to visualise and measure styloid processes. Patients were diagnosed with Eagle’s Syndrome in setting of presence of symptoms with tenderness or palpable styloid process over ipsilateral tonsillar fossa and NCCT finding of ipsilateral styloid process longer than 30 mm. All patients were then counselled in detail regarding nature of disease, treatment options available and follow up duration of up to 6 months.

Patients who opted for conservative management, were administered with Tab Gabapentin 300–600 mg/day and Tab Carbamazepine, started as 100 mg single daily dose and gradually increased up to 800 mg/day in divided doses for 3–4 weeks. Para-tonsillar resection of styloid process with intraoral approach was offered as surgical management for those who opted for it. Under general anaesthesia, an incision was given over superior pole of tonsillar fossa with cold steel method and with carefully sparing surrounding tonsillar tissue, styloid process was exposed and reduced. Post-operative period for all patients was largely uneventful saving pain and trismus in few cases, which was successfully managed with oral analgesics. All patients were followed up on 1, 3- and 6-months post intervention, their pain VAS scores were recorded pre and post intervention and during each follow up visit and statistically analysed using SPSS ver 25.0.

Results

In this study, total of 15 subjects participated (9 females and 6 males, Male: Female ratio 3:2), with mean age of 41.6 years and range of 26–70 years. The duration of symptoms was in range of 7–24 months with mean duration of 12.27 months. Symptoms with which they presented were throat pain with hemifacial radiation, pharyngeal foreign body sensation, referred otalgia, odynophagia and in one case, giddiness. 47% subjects were found suffering from two or more symptoms, most common being throat pain with hemifacial radiation and pharyngeal foreign body sensation followed by odynophagia (details are as per Table 1). On palpation of tonsillar fossa, peculiar findings of tenderness or palpable styloid process or both were found in 100% of cases, with few cases (statistically non-significant) reporting exacerbation of symptoms as well.

Table 1.

Distribution of symptoms among study subjects

| s. no | Symptoms of Eagle’s syndrome | Frequency (n = 15) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Throat pain with hemifacial radiation | 53% |

| 2 | Pharyngeal foreign body sensation | 53% |

| 3 | Odynophagia | 20% |

| 4 | Referred otalgia | 27% |

| 5 | Giddiness | 0.07% |

On NCCT scan of face and neck, mean length of right styloid process was 32.60 mm with range of 55–11 mm and standard deviation of 11.40 mm, mean length of left styloid process was 34 mm with range of 47–22 mm and standard deviation of 6.3 mm. Mean length of styloid process of affected side was 39 mm with range of 55–32 mm and standard deviation of 6 mm (n = 15).

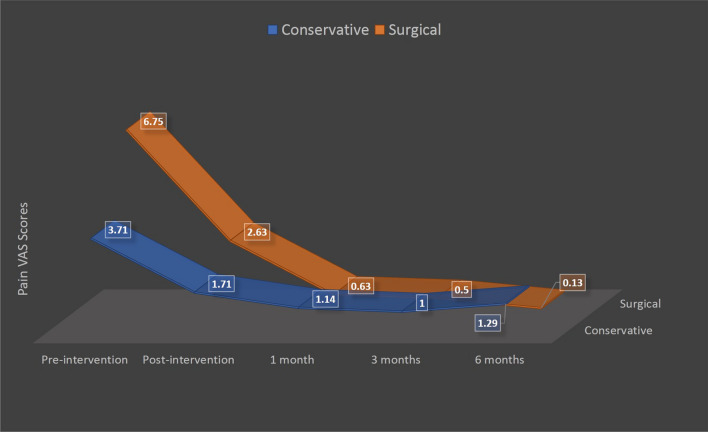

Conservative management was choice of 46.7% (7 out of 15) patients where they were administered with medications as per study protocol. 53.3% (8 out of 15) patients chose to undergo para-tonsillar resection of styloid process with intraoral approach as definitive management and all patients were followed up till 6 months post intervention. Pain VAS scores of all patients were recorded pre-intervention, post-intervention (on completion of 4th week of treatment in case of conservative management group and on 2nd post-operative day in surgical management group), and on follow up visits on 1,3 and 6 months. Mean pain VAS scores of conservative management group on pre-intervention, post-intervention and follow up visits of 1,3 and 6 months were 3.71, 1.71, 1.14, 1 and 1.29 respectively, and that of patients in surgical management group were 6.75, 2.63, 0.63, 0.5 and 0.13 respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mean pain VAS scores of patients managed with conservative and surgical modalities

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS 25.0 and p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Among patients in conservative treatment group, on comparison of pre-intervention mean pain VAS scores with that of 6 months follow up visit using 95% confidence interval (CI) and 6 degrees of freedom (df), p value was 0.012 (Student’s paired t test) which was statistically significant. When mean scores of similar durations were compared among patients of surgical management group, p value came out to be < 0.0001, which was statistically extremely significant (using 95% CI and df = 7, Student’s paired t test) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of pain VAS scores—pre-intervention vs 6 months follow up visit

| Treatment group | Mean | SD | p value * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative management (n = 7) | |||

| Pre-intervention | 3.71 | 0.95 | 0.012 |

| 6 months follow up | 1.29 | 1.7 | |

| Surgical management (n = 8) | |||

| Pre-intervention | 6.75 | 1.16 | < 0.0001 |

| 6 months follow up | 0.13 | 0.35 | |

*Student’s paired t test

On comparison of end of follow up visit mean pain VAS scores (at end of 6 months) among two groups, using 95% CI and df = 13, p value was 0.05 which was statistically significant in favour of surgical management group (Student’s unpaired t test) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of pain VAS scores of 6 months follow up visit among conservative and surgical management group

| Pain VAS scores | Conservative management | Surgical management | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 1.29 | 0.13 | 0.05 |

| SD | 1.7 | 0.35 |

*Student’s unpaired t test

Subgroup Analysis

On comparison of mean pain VAS scores of 3 months follow up visit (0.5) with that of 6 months (0.13) in case of surgical management group, using 95% CI and df = 7, in spite of its decreasing trend (as depicted in Fig. 1), results were statistically insignificant with p = 0.07 (Student’s paired t test). When similar analysis was performed in cases of conservative management group and mean pain VAS scores of 3 months (1.00) with that of 6 months (1.29), there was an increase in mean scores (as seen in Fig. 1) with statistically insignificant results (95% CI, df = 6, p value = 0.35, Student’s paired t test). We then tried to analyse which management modalities gave better results in 3 months and compared their mean pain VAS scores and found results comparable and statistically insignificant using 95% CI, df = 13 and p value = 0.2 (Student’s unpaired t test) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis of mean pain VAS scores of 3 months and 6 months follow up visit

| Management group | 3 months follow up | 6 months follow up | p value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Conservative management | 1.00 | 1.15 | 1.29 | 1.7 | 0.35 |

| Surgical management | 0.5 | 0.53 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.07 |

| p value** | 0.2 | 0.05 | |||

*Student’s paired t test

**Student’s unpaired t test

Discussion

Chronicled in mid-seventeenth century by Demanchetis, an Anatomist, as ossification of stylohyoid ligament; first clinically recorded by Weinlecher in 1872 and classically described by Dr Watt Weems Eagle, an American Otorhinolaryngologist in 1937, this eponymous syndrome is one of the diagnostic intrigues caused by elongated styloid process (normal length being 25–30 mm with range from 17.2–47.7 mm) and resulting in multitude of symptoms [2–5]. As described by Dwight in his landmark article in 1907, styloid process has four components, tympanohyal, stylohyal, ceratohyal and hypohyal (from proximal to distal). He described occasional ossification which was found at junction of ceratohyal and hypohyal parts, possibly leading to ossification of stylohyoid ligament (later described as ectopic calcification) and elongation of styloid process leading to this syndrome [6, 7]. Rare and difficult to diagnose and manage, even after three centuries of documented experiences, this syndrome may present as persistent nagging and stabbing throat pain, particularly in tonsillar fossa, with or without ipsilateral hemifacial radiation or/and referred ipsilateral otalgia. Patient may experience a pharyngeal foreign body sensation, odynophagia, dysphagia or chronic pain similar to glossopharyngeal neuralgia with possible exacerbation during neck movement, mastication and deglutition. There may be cervical pain and painful restriction on neck movement and jaw movement associated with temporary hypersalivation and hoarseness [1, 2, 8]. There are reports on elongated styloid process impinging on carotid artery, causing giddiness and blackouts on turning head laterally, mimicking Carotid artery syndrome or Carotidynia and called Stylocarotid syndrome [9, 10].

Due to its rarity, incidence of Eagle’s Syndrome quoted in literature varies, from 1.4–30% and as is in our study, female preponderance is known [1, 11, 12]. Similar is its pathophysiology, which is quite varied and makes its presentation so multidimensional. Elongated/angulated styloid process can impinge on glossopharyngeal nerve, branches of trigeminal nerve or vagus itself. Damage to styloid process during rather overenthusiastic tonsillectomy surgery can result in insertion tendinitis or rheumatoid styloiditis; or the fractured bony fragment may medialise and compress adjoining neurovascular structures [13–16]. Very rarely it may even cause generalised tonic clonic seizures due to glossopharyngeal neuralgia [17] or may even contribute secondarily in failure in emergency intubation and resulting in death [18]. Clinical examination may reveal findings which may differ strikingly, but tenderness or palpable bony prominence of elongated styloid process on digital palpation of tonsillar fossa with or without exacerbation of symptoms may direct clinician’s suspicion. Objective imaging evidence is must, preferably a NCCT scan with three-dimensional reconstruction with coronal and sagittal reformatting, which may just not enable one to visualise ossified stylohyoid ligament or elongated styloid process but also to measure it [10]. Despite of the multitude of presentations, criteria for clinical diagnosis remains same as was described by Eagle in 1937, i.e. combination of this examination finding with radiological evidence in a symptomatic patient, which was followed in our study [2].

With such contrasting features, this condition may have many differential diagnoses, viz., glossopharyngeal neuralgia, carotid artery syndrome, trigeminal neuralgia, temporal arteritis, temporo-mandibular joint disorders, chronic tonsillitis or pharyngitis or even submandibular sialadenitis or mastoiditis [19]. Sharp clinical acumen, knowledge of this condition and its varied presentations and availability of imaging modalities may assist a young Otorhinolaryngologist with finding correct diagnosis.

Once diagnosed, Eagle’s syndrome can be treated both conservatively as well as well as surgically. While many experienced Otorhinolaryngologists may prefer surgical management, there is plethora of literature with conservative school of thought, which include a complex combination of medications. As the basic pathology is neuralgia, Carbamazepine (started as low dose, 100 mg single dose daily and increased up to 600–800 mg/day in divided doses for 3–4 weeks) in combination of Gabapentin (300–600 mg/day) or Pregabalin (75 mg/day) with or without injecting tonsillar fossa with 2–4% lignocaine and hydrocortisone or stellate ganglion blocks (once per week) are considered very effective therapy [20] which was followed in this study. Many authors also prefer to give supportive therapy with antihistaminic, neuroleptics, anti-depressants, vasodilators and sodium valproate [20, 21]. Conservative management, as mentioned in literature, lasts for 2–4 weeks, and is known to give good short-term results [20, 22]. There seems to be paucity of literature on long term follow up of patients on conservative management but recurrences of symptoms shortly after completion of treatment regimen is known necessitating replication of therapy. In a study by Gervickas et al., with conservative management, initial betterment with recurrence was seen in 52.6%, overall improvement was observed in 16.5% and failure of treatment was noticed in 30.9% of study population [20]. In this study, there was statistically significant improvement immediately after conservative management finished, which lasted for 3 months for most of the subjects, but recurrence of symptoms was seen after that.

Surgical management includes resection of styloid process with intra or extraoral approach, intraoral being preferred by most of Otorhinolaryngologists as mentioned in literature, possibly due to better surgical and tissue knowledge. Intraoral approach includes exposing tip of styloid process after tonsillectomy, either with cold-steel or laser/coblation method or with a para-tonsillar approach (which was followed in this study), followed by resection of styloid process. An incision is given over superior pole of tonsillar fossa, and using blunt dissection surrounding tonsillar tissue is spared and tip of styloid process is exposed using curved artery forceps., periosteum incised and subperiosteal dissection continued till the base of styloid process while keeping muscles and soft tissue retracted with either vein loop or broad artery forceps. Styloid process is then fractured with a bone nibbler or rongeur while stabilising tip with firm hold with Allis or straight artery forceps preventing muscular retraction of fractured segment, and removed carefully in toto [1, 23, 24]. Postoperative period includes severe pain and trismus which may last for 2–3 days and can easily be managed with oral analgesics and muscle relaxants. Extra-oral or transcervical approach has been advocated by few authors but not without its demerits which include visible scar, possible facial nerve damage and deep neck space infection [1, 15, 23]. Preferred by most authors, surgical management, although giving difficult time to patients for few immediate post-operative days, provides with enough, lasting and statistically significant results as was seen in this study.

Conclusions

Eagle’s Syndrome is a controversial, much debated but irrefutable condition once diagnosed and patients are known to be running pillar to post, from General Physicians. Neurologists, Dental and Oral-Maxillofacial Surgeons, Otorhinolaryngologists and even Psychiatrists, and thus, as was felt by Watt W. Eagle, knowledge of its presentation, clinical examination and treatment is essential for all doctors and surgeons. A combination of its peculiar tonsillar fossa palpatory finding with objective evidence of elongated styloid process in a symptomatic patient generally clinches the diagnosis. Conservative management gives good enough results in short term, but recurrences are known after 3 months of therapy. Intraoral resection of styloid process remains the preferred surgical management notwithstanding the pain and trismus which are known immediate surgical complications, but easily manageable and provide long-term relief (6 months and beyond), much better than conservative management.

Limitations

This study, although could bring some clarity on management of Eagle’s Syndrome, however, remains weak due to being observational in nature, lack of large sample size and no randomisation resulting in unequivocal distribution of subject in study groups. There is a felt need of large scaled multicentric randomised controlled trials/meta-analyses for more objective comparison between conservative and surgical management for truer generalisation and to form guidelines for conservative management for larger applicability.

Funding

Nil.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chrcanovic BR, Custódio ALN, de Oliveira DRF. An intraoral surgical approach to the styloid process in Eagle’s syndrome. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;13(3):145–151. doi: 10.1007/s10006-009-0164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eagle WW. Elongated styloid processes: report of two cases. Arch Otolaryngol. 1937;25(5):584–587. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1937.00650010656008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rechtweg JS, Wax MK. Eagle's syndrome: a review. Am J Otolaryngol. 1998;19(5):316–321. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(98)90005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufman SM, Elzay RP, Irish EF. Styloid process variation: radiologic and clinical study. Arch Otolaryngol. 1970;91(5):460–463. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1970.00770040654013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russel T. Eagle’s syndrome: diagnostic consideration and report of case. J Am Dent Assoc. 1977;94(3):548–550. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1977.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dwight T. IX. Stylo-hyoid ossification. Ann Surg. 1907;46(5):721–735. doi: 10.1097/00000658-190711000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gokce C, Sisman Y, Sipahioglu M. Styloid process elongation or eagle’s syndrome: is there any role for ectopic calcification? Eur J Dent. 2008;2:224. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1697384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beder E, Ozgursoy OB, Ozgursoy SK. Current diagnosis and transoral surgical treatment of Eagle’s syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63(12):1742–1745. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eagle W. Elongated styloid process: symptoms and treatment. Arch Otol. 1958;67(2):172–176. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1958.00730010178007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demirtaş H, Kayan M, Koyuncuoğlu HR, Çelik AO, Kara M, Şengeze N. Eagle syndrome causing vascular compression with cervical rotation: case report. Pol J Radiol. 2016;81:277. doi: 10.12659/PJR.896741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Correll RW, Jensen JL, Taylor JB, Rhyne RR. Mineralization of the stylohyoid-stylomandibular ligament complex: a radiographic incidence study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1979;48(4):286–291. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(79)90025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keur J, Campbell J, McCarthy J, Ralph W. The clinical significance of the elongated styloid process. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;61(4):399–404. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Härmä R. Stylalgia: clinical experiences of 52 cases. Acta Oto-laryngol. 1967;63(sup224):149–155. doi: 10.3109/00016486709123570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moffat D, Ramsden R, Shaw H. The styloid process syndrome: aetiological factors and surgical management. J Laryngol Otol. 1977;91(4):279–294. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100083699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strauss M, Zohar Y, Laurian N. Elongated styloid process syndrome: intraoral versus external approach for styloid surgery. Laryngoscope. 1985;95(8):976–979. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198508000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frommer J. Anatomic variations in the stylohyoid chain and their possible clinical significance. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1974;38(5):659–667. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(74)90382-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malik Y, Dar JA, Almadani AAR (2015) Seizures with an atypical aetiology in an elderly patient: Eagle's syndrome—how does one treat it? BMJ Case Rep 2015:bcr2014206136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Gupta A, Aggrawal A, Setia P. A rare fatality due to calcified stylohyoid ligament (Eagle syndrome) Med Leg J. 2017;85(2):103–104. doi: 10.1177/0025817217695139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fini G, Gasparini G, Filippini F, Becelli R, Marcotullio D. The long styloid process syndrome or Eagle's syndrome. J Cranio Maxillofac Surg. 2000;28(2):123–127. doi: 10.1054/jcms.2000.0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gervickas A, Kubilius R, Sabalys G. Clinic, diagnostics, and treatment peculiarities of Eagle's syndrome. Stomatol Balt Dent Maxillofac J. 2004;6:11–13. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawasaki M, Hatashima S, Matsuda T. Non-surgical therapy for bilateral glossopharyngeal neuralgia caused by Eagle’s syndrome, diagnosed by three-dimensional computed tomography: a case report. J Anesth. 2012;26(6):918–921. doi: 10.1007/s00540-012-1437-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han MK, Do Wan Kim JYY. Non surgical treatment of Eagle's syndrome-a case report. Korean J Pain. 2013;26(2):169. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2013.26.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al Weteid A, Miloro M. Transoral endoscopic-assisted styloidectomy: how should Eagle syndrome be managed surgically? Int J Oral Max Surg. 2015;44(9):1181–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scheller K, Eckert AW, Scheller C. Transoral, retromolar, para-tonsillar approach to the styloid process in 6 patients with Eagle's syndrome. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2014;19(1):e61–66. doi: 10.4317/medoral.18749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]