Abstract

The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and outcome using the maxillary swing approach for the management of extensive nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. A retrospective case series analysis in a tertiary care centre revealed eighteen cases with extensive nasal angiofibroma operated using the maxillary swing approach between 2011 and 2017. All patients had tumour extension to the lateral most portions of the infratemporal fossa with complete occupation and destruction of the lateral wall of the sphenoid sinus causing abutment to the cavernous sinus and complete involvement of the pterygopalatine fossa and pterygoid base. One patient displayed full occupancy of the maxillary sinus as a consequence of erosion of the posterior and medial walls of the maxillary sinus. All patients underwent tumour excision using the maxillary swing approach. Patients were followed up for a minimum period of 1 year after surgery. The maxillary swing approach gave optimal exposure of the entire central skull base including the infratemporal fossa and its extreme lateral and superior aspects. Adequate tumour exposure and vascular control could be achieved in all cases resulting in complete tumour excision. The mean operative time was 3 h 15 min. Post-operative healing was satisfactory with palatal fistula formation in four cases and all patients remaining disease-free up to the present time. One had minimal misalignment of the halves of the upper jaw and two had epiphora, of which one required dacryocystorhinostomy. The maxillary swing is an effective approach in the management of extensive nasopharyngeal angiofibroma and leads to optimal anatomical exposure with minimal morbidity.

Keywords: Angiofibroma, Maxillary swing, Infra temporal fossa, Advanced stage

Introduction

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas are rare, highly vascular, non-encapsulated tumours accounting for 0.05% of all head and neck neoplasms [1]. They most commonly occur in young males, between the ages of 14 and 25 years [2].

Classically, JNAs become symptomatic with unilateral nasal obstruction and epistaxis [2, 3]. Advanced lesions may cause facial swelling, proptosis, cranial neuropathy, and massive haemorrhage [2].

Regardless of the site or the origin, these tumours are locally invasive (20%–30% of the cases have an intracranial extension [4]) and grow beyond the maxillary sinus, extending into the ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses, the nasopharynx, and laterally into the infratemporal fossa [5, 6]. In extreme cases, JNAs invade the orbit via either direct extension through the lamina papyracea or superior wall of the maxillary sinus, or via the orbital fissures [5, 7]. Intracranial invasion at the middle fossa commonly occurs through the pterygomaxillary space and Meckel cave or by extension into the sphenoid and ethmoid sinuses and erosion into the sella turcica, planum sphenoidale, and anterior skull base [8].

Treatment options for JNAs include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and surgery, the latter being the gold standard [9]. The decision regarding approach is usually made after reviewing radiographic studies to assess tumor extent, blood supply, and presence or absence of intracranial extension. There are several surgical approaches described in the past each having its advantage and disadvantage.

While the limited nasopharyngeal angiofibromas can be removed endoscopically, a number of surgical approaches have been described for the excision of advanced and extensive nasopharyngeal angiofibromas: infratemporal fossa type C approach [10], craniofacial approaches [1, 11], maxillary swing approach [12] and, more recently, the endoscopic endonasal approach [13–15]. The maxillary swing technique was first described to be used in cases with carcinoma of the nasopharynx. The requirement for excellent exposure of the cranial base and relevant neurovascular structures is crucial in any of these approaches.

The purposes of the current study were to review cases of advanced or extensive nasopharyngeal angiofibromas operated in a tertiary care referral institute using the maxillary swing technique and to report the outcomes, complications and feasibility of this unique approach.

Methods

A retrospective review was carried out on the clinical and operative records of 18 cases of Fisch IIIb/IV nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (NPA) operated between 2011–2017, where the ‘maxillary swing’ approach was used for tumor removal and where other surgical approaches were not feasible due to the extent of disease as assessed by pre-operative clinical and radiological findings. All patients who had tumour extension to the lateral-most portions of the infratemporal fossa (Fig. 1) with or without occupation and destruction of the lateral wall of the sphenoid sinus causing abutment to the cavernous sinus and complete involvement of the pterygopalatine fossa and destruction of the pterygoid root were included in the study.

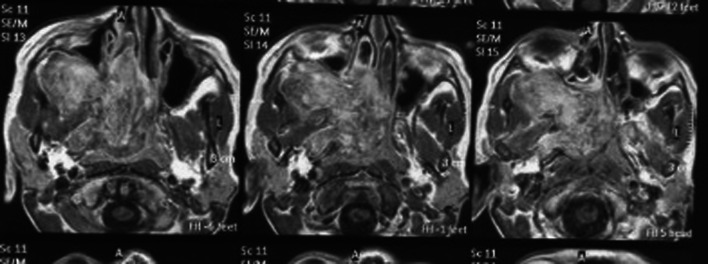

Fig. 1.

MRI image showing enhancing lobulated soft tissue epicentered in spheno palatine foramen reaching up to right infratemporal fossa

We used Modified Fisch’s classification as proposed by Andrews et al. [16] and cases included in the study were Stages IIIb and IVa.

Patients with radiographic evidence of intracranial extension were excluded from study. Patients and relatives were informed about nature of the disease, extent, possible surgical options with their advantages and disadvantages. Written informed consents were taken from all patients before embolization and surgery. Pre-operative embolization of feeding vessels was planned 48 h before surgery. A 4-week course of flutamide (10 mg/kg/day) was administered to two patients where embolization was not feasible or possible. All patients were operated on using the maxillary swing approach. Intra-operative variables recorded were operative time, intra-operative blood loss, and blood transfusion details.

Technique

All patients were operated under general anaesthesia with orotracheal intubation. Bilateral tarsorrhaphy was performed. A Weber–Ferguson–Longmire incision was made over the ipsilateral hemiface and midline palate, extending in between the hard and soft palate on the ipsilateral side, and then curving around the maxillary tuberosity and ending there without extending it sub labially (Fig. 2). The incision was deepened over the face to divide the periosteum and expose the bone. A minimal amount of periosteum was elevated to expose bone for relevant osteotomies leaving the rest and cheek flap attached to the anterior wall of the maxilla. A miniplate was positioned on the bilateral alveolar processes and appropriate holes were drilled for positioning screws later. Osteotomies were performed at the frontal process of the maxilla, inferior orbital rim, maxillo-zygomatic suture, midline palate and finally to separate the maxilla from the pterygoid process. The entire maxilla including the hard palate was then swung and reflected laterally while attached to the cheek flap, exposing the entire nasopharynx, infratemporal fossa and central cranial base. This lateral reflection of maxilla leads to a superior exposure encompassing the entire nasopharynx, oropharynx and oral cavity whereby much larger angle of vision is achieved because of inclusion of oral cavity in the surgical exposure (Fig. 3). The tumour was removed in toto.(Fig. 5) The specimen was inspected closely on all surfaces for completeness. The pterygoid process, sphenoid sinus and the vidian canal were inspected for any possible tumour remnants (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Intra op picture showing Weber–Ferguson–Longmire incision without sublabial extension

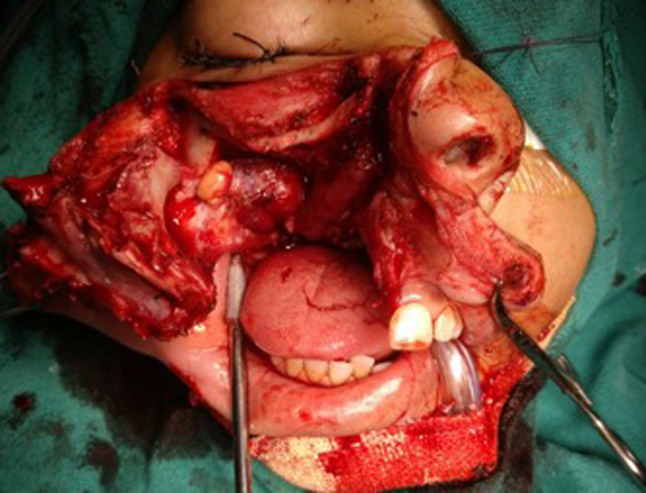

Fig. 3.

Intra op picture showing wide exposure achieved with maxillary swing technique

Fig. 5.

Postoperative specimen of the tumor in toto

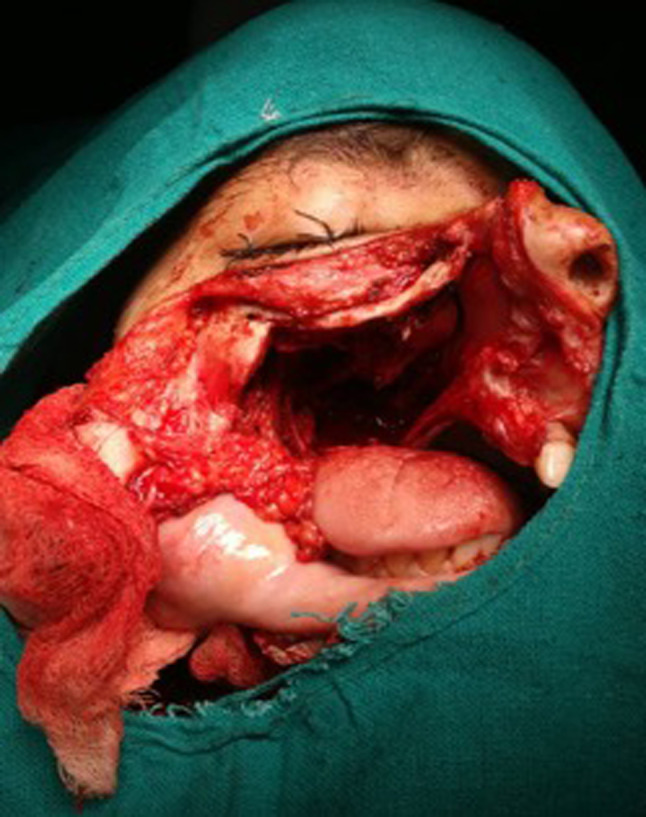

Fig. 4.

Intra operative picture following complete removal of tumor

The maxilla was repositioned and realigned using miniplates and screws at the osteotomy sites(frontal process of the maxilla, maxillo-zygomatic suture and alveolar process)(Fig. 5) The wound was closed primarily after placement of packs (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Postoperative picture following realignment of the maxilla

Patients were followed up post-operatively for a minimum period of 3 year using computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging and diagnostic nasal endoscopy to detect any residual or recurrent disease.

Results

All patients were adolescent males with an age range of 15–20 years and with a mean age of 16.4 years. All patients were primary cases with no history of previous surgery or radiation therapy. Most common presenting complaints were nasal obstruction and recurrent epistaxis, followed by proptosis, trismus and facial swelling.

Contrast enhanced computed tomography with angiography revealed that, in 16 cases, the feeding vessel was the internal maxillary branch of the external carotid artery and in 2 cases the ophthalmic branches of the internal carotid artery were seen to supply the intracranial portion of the lesion. In 16 cases, selective embolization of the feeding vessels was performed 48 h before surgery using gelfoam. However, the embolization procedure could not be performed in two cases due to inability to insert an adequately sized catheter into the feeding vessel. Both of these patients were administered a 4-week course of flutamide at a 10-mg/kg/ day dosage after evaluation and monitoring of serum testosterone levels and liver function tests. One patient reported significant resolution of symptoms during this period. No significant adverse effects were observed in either case except for mild temporary breast tenderness. Surgery in both of these cases was commenced in the week following completion of drug therapy. Intra-operative tumor removal was complete in all cases with no remnants of disease. The exposure provided by swinging the maxilla was excellent in all cases, enabling thorough inspection and assessment of the cranial base and infratemporal fossa with adequate vascular control. No difficulty was reported in swinging the maxilla attached to the cheek flap. All patients had their vision preserved in the postoperative period and no one experienced any CSF leakage. No significant cosmetic deformity was noted.

The average duration of surgery was 3 h 15minutes with a mean intra-operative blood loss of 900 ml. All patients required intra- operative blood transfusions. No transfusion- associated adverse effect was observed in any case.

Post-operative recovery was complicated by the formation of palatal fistulas in four patients. Two patients had spontaneous closure of the fistula by the 14th post-operative day, whereas two required surgical closure under local anaesthesia 2 months after surgery. Two patients developed epiphora with one patient requiring dacryocystorhinostomy for relief. One patient had minimal but cosmetically acceptable mal-alignment of the upper incisors. During the minimum follow-up period of 1 year, no case showed any residual or recurrent lesion, as viewed on computed tomography, MRI and diagnostic nasal endoscopy.

Discussion

Surgical management of nasopharyngeal angiofibromas with intracranial extension has traditionally been associated with incomplete removal, uncontrollable haemorrhage, neurological deficits and recurrence [17, 18]. Involvement or extension to the infratemporal fossa, sphenoid sinus, pterygoid base, cavernous sinus, foramen lacerum and anterior cranial fossa has been associated with increased risk of recurrence and incomplete tumor removal [18]. All patients in our series had extreme lateral involvement of the infratemporal fossa abutting the mandibular ramus, erosion of the pterygoid base and complete occupation of the sphenoid sinus.

Radiotherapy has been advocated as an alternative treatment modality in angiofibromas with intracranial or significant extracranial extension or as an adjunct to surgery where there has been incomplete excision of lesions [19]. However, radiotherapy should preferably be avoided because of confirmed risks of secondary malignancies, retarded facial growth, malignant transformation of the tumor and increased chances of bone flap osteomyelitis and necrosis after surgery [19, 20].

Wei and colleagues [21] first described the maxillary swing as an approach to surgical management of recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinomas post-radiotherapy and for placement of brachytherapy tubing. Bone flap osteomyelitis and necrosis are minimal with this technique, as the maxilla is attached to the facial artery supplying the cheek flap. This has a significant advantage when compared to other approaches for the management of extensive lesions such as maxillary removal and re-insertion and complex craniofacial approaches where bone flap necrosis can be a complication, more so in post-radiotherapy cases [11, 22].

One of the most crucial aspects of all craniofacial approaches in the management of angiofibromas is adequate exposure of the anterior and middle cranial base [23].

The maxillary swing approach allows complete exposure of the midline and lateral skull base, with possibilities of further exposure of the temporal and infratemporal fossa by performing a lateral osteotomy at the zygomatic bone, and enabling an infratemporal craniotomy by elevation and retraction of the temporalis muscle [12]. This effectively provides comprehensive exposure of the clivus down to the fourth cervical vertebra. In their series, Dubey and colleagues [12] operated extensive angiofibromas using the total maxillary swing technique and achieved complete excision in all cases with acceptable cosmetic outcomes and temporary neural palsies in cases with significant intracranial extension.

Another significant advantage of the maxillary swing technique is the near-complete preservation of both the anterior and posterior walls of the maxilla as careful realignment maintains the entire anatomy of the central cranial base and maxilla.

Mid facial degloving once initiated cannot be converted to maxillary swing thus making both the procedures mutually exclusive.

Although providing adequate exposure of the extreme lateral cranial base and infratemporal fossa, the infratemporal fossa approach used by Andrews and colleagues [10] does not achieve adequate midline exposure. Midline and contralateral exposure, however, is excellent in the maxillary swing approach and can be increased by incising the posterior septum and retracting it downwards [12]. The infratemporal approaches use a subtotal petrosectomy with blind sac closure and hence result in conductive hearing loss along with temporal region defects. No such complication is observed with the maxillary swing technique.

Other complex craniofacial approaches that have been used recently for management of extensive angiofibroma are the orbito-zygomatic with trans basal approach [11], the infratemporal fossa with facial translocation approach11, and the expanded endoscopic approach with staged resections [13]. Most otolaryngologists and head and neck surgeons are familiar with the procedure for total maxillectomy and most steps in this procedure are similar to the maxillary swing approach except for re-alignment of the maxilla attached to the cheek flap, making this procedure technically less challenging and time consuming than the above-mentioned approaches. Endoscopic staged operations often require lasers [13] and coblation devices [24], which incur a significant cost to the procedure and patient, and this is often a limiting factor in a resource limited set-up, which may ultimately have to resort to radiation therapy for complete tumor eradication [24].

In the present study, the maxilla was swung even in a case with complete destruction of the posterior and medial walls and with partial destruction of the anterior wall of the maxilla. We did not observe any difference in intra-operative blood loss in cases that could be embolized and those who were given flutamide and were not embolised. Follow-up imaging does not show any evidence of tumour recurrence or tumour remnant in any of the cases (Table 1).

Table 1.

Andrew’s (modified Fisch) classification [16]

| I | Limited to the nasopharynx and nasal cavity, bone destruction negligible, or limited to the sphenopalatine foramen |

|---|---|

| II | Invades the pterygopalatine fossa or the maxillary, ethmoid or sphenoid sinus with bone destruction |

| III a | Invades the infratemporal fossa or the orbital region without intracranial involvement |

| III b | Invades the infratemporal fossa or orbit with intracranial extradural (parasellar) involvement |

| IV a | Intracranial intradural tumour without infiltration of the cavernous sinus, pituitary fossa, or optic chiasm |

| IV b | Intracranial intradural tumour with infiltration of the cavernous sinus, pituitary fossa, or optic chiasm |

Conclusions

The maxillary swing is an effective approach in the management of extensive nasopharyngeal angiofibromas and leads to an optimal anatomical exposure with minimal morbidity. It provides optimum exposure of the central, anterior and antero-lateral cranial base, leading to complete surgical excision of extensive juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas with acceptable cosmetic outcomes and minimal morbidity. In cases where Endoscopic excision is not possible or the extension is too extensive for the surgeon to be confident of complete excision, Maxillary Swing approach is a safe and effective alternate. The only limitation of this approach is that one cannot convert the once initiated midfacial degloving approach to it. Hence, these two approaches are mutually exclusive.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declare that they don’t have conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Neena Chaudhary, Email: drneenachaudhary@hotmail.com.

Shweta Jaitly, Email: jaitly_shweta@yahoo.com.

Rajeev Kumar Verma, Email: drrajeevkumar85@gmail.com.

Shashank Gupta, Email: sha2nkgupta@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Bales C, Kotapka M, Loevner LA, Al-Rawi M, Weinstein G, Hurst R, et al. Craniofacial resection of advanced juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:1071–1078. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.9.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fagan JJ, Snyderman CH, Carrau RL, Janecka IP. Nasopharyngeal angiofibromas: selecting a surgical approach. Head Neck. 1997;19:391–399. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199708)19:5<391::AID-HED5>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bremer JW, Neel HB, III, DeSanto LW, Jones GC. Angiofibroma: treatment trends in 150 patients during 40 years. Laryngoscope. 1986;96:1321–1329. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198612000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harwood AR, Cummings BJ, Fitzpatrick PJ. Radiotherapy for unusual tumors of the head and neck. J Otolaryngol. 1984;13:391–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danesi G, Panciera DT, Harvey RJ, Agostinis C. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: evaluation and surgical management of advanced disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:581–586. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sennes LU, Butugan O, Sanchez TG, Bento RF, Tsuji DH. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: the routes of invasion. Rhinology. 2003;41:235–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruz AA, Atique JM, Melo-Filho FV, Elias J., Jr Orbital involvement in juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: prevalence and treatment. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;20:296–300. doi: 10.1097/01.IOP.0000132163.00869.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lloyd G, Howard D, Phelps P, Cheesman A. Juvenile angiofibroma: the lessons of 20 years of modern imaging. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:127–134. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100143373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleier BS, Kennedy DW, Palmer JN, Chiu AG, Bloom JD, O’Malley BW., Jr Current management of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: a tertiary center experience 1999–2007. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23:328–330. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrews JC, Fisch U, Valavanis A, Aeppli U, Makek MS. The surgical management of extensive nasopharyngeal angiofibromas with the infratemporal fossa approach. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:429–437. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198904000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherekaev VA, Golbin DA, Kapitanov DN, Roginsky VV, Yakovlev SB, Arustamian SR. Advanced craniofacial juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Description of surgical series, case report and review of literature. Acta Neurochir. 2011;153:499–508. doi: 10.1007/s00701-010-0922-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubey SP, Molumi CP, Apaio ML. Total maxillary swing approach to the skull base for advanced intracranial and extracranial angiofibroma. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:1671–1676. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31822f3c96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hackman T, Synderman CH, Carrau R, Vescan A, Kassam A. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: the expanded endonasal approach. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23:95–99. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Synderman CH, Pant H, Carrau RL, Gardner P. A new endoscopic staging system for angiofibromas. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136:588–594. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Douglas R, Wormald PJ (2006) Endoscopic surgery for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: where are the limits. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 14:1–5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Andrews JC, Fisch U, Valavanis A, et al. The surgical management of extensive nasopharyn- geal angiofibromas with the infratemporal fos- sa approach. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:429–437. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198904000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radkowski D, McGill T, Healy GB, Ohlms L, Jones DT. Angiofibroma: changes in staging and treatment. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:122–129. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1996.01890140012004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herman P, Lot G, Chapot R, Salvan D, Huy P. Long-term analysis of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas: analysis of recurrence. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:141–147. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199901000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JT, Chen P, Safa A, et al. The role of radiation therapy in the treatment of advanced juvenile angiofibroma. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1213–1220. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200207000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reddy KA, Mendenhall WM, Amdur RJ, et al. Long-term results of radiation therapy for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Am J Otolaryngol. 2001;22:172–175. doi: 10.1053/ajot.2001.23458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei WI, Ho CM, Yuen PW, Fung CF, Sham JS, Lam KH. Maxillary swing approach for resection of tumors in and around the nasopharynx. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:638–642. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1995.01890060036007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suarez C, Llorente JL, Munoz C, Garcia LA, Rodrigo JP. Facial translocation approach in the management of central skull base and infratemporal fossa tumors. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1047–1051. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200406000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Origitano TC, Petruzzelli GJ, Leonetti JP, Vandevender D (2006) Combined anterior and anterolateral approaches to the cranial base: complication analysis, avoidance and management. Neurosurgery 58(4 Suppl 2):ONS 327–ONS 336 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Pierson B, Powitzky R, Digoy GP. Endoscopic coblation for the treatment of advanced juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Ear Nose Throat J. 2012;9:432–438. doi: 10.1177/014556131209101007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]