Abstract

To study the clinical presentation, management and mechanism of fractured outer metallic tracheostomy tube presenting as tracheobronchial foreign body. A retrospective chart review patients with fracture outer metallic tracheostomy tube. Data regarding the patients’ demographic data, diagnosis, clinical presentation, type of tracheostomy tube and site of fracture were analyzed. Total 4 cases of fracture outer metallic tracheostomy tube were found. There were 3 males and 1 female, average age 52.75 years, range 31–76 years. The common presentation were dyspnea, intolerable cough and decreased breath sound in 4(100%), 2(50%) and 2(50%) cases. The most serious presentation was cardiac arrested 1 case. The dislodged tube were retrieved by flexible and rigid bronchoscopy. The most common site of fracture were outer tube at mid shaft 3 cases (75%). All of this site had corrosion. Only 1 case (25%) was fracture at junction between neck plate and tube without corrosion. The average time of usage metallic tracheostomy tube was 24 days, range 3–34 days. Fracture tracheostomy tube is rare and serious medical emergency. The patients, caregivers and physicians should recognition and prompt action. Flexible or rigid bronchoscopy via tracheostoma can successfully removal the dislodge part. The mechanism of fracture may come from several factors. The defective manufacturer, stagnation of alkaline bronchial secretion, recurrence process of removal, cleaning and boiling of the tube can cause mechanical stress and degradation of passive film of the tubes. The patient education regarding the maintenance and regular checked up can possibly extinguish this complication.

Keywords: Foreign bodies, Fracture, Respiratory aspiration, Tracheostomy

Introduction

Airway tracheostomy is a common form of life support. The procedure is safe and the mortality rate < 5% [1]. Complications may be classified as early or late. The early complications are hemorrhage during or after operation, pneumothorax, obstruction of the tracheostomy tube, tube displacement, and wound infection. The late complications are granuloma formation, erosion of the innominate artery, tracheal stenosis, and development of a tracheo-esophageal fistula [2, 3]. Fracture of the metallic tracheostomy tube in the acute phase is an extremely rare complication. It is unlikely that a tracheostomy tube per se can obstruct the airway. We report four instances of fracture of metallic tracheostomy tubes. One case was severe, associated with cardiac arrest. The clinical presentations of such fractures, appropriate interventions and management, and the fracture mechanisms are discussed.

Methods

We reviewed fractures of metallic tracheostomy tubes that presented as tracheobronchial foreign bodies over a 3-year period at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand between January 2014 and Febuary 2017. This study was approved by Ethics Committee and Institutional Review Board No. 207/60. We recorded demographic data including age, sex, indications for tracheostomy, clinical presentations, and durations of intubation. We reviewed chest radiographs to define the locations of the dislodged tubes, and we discuss the interventions used to remove the tubes.

Results

The patient male:female ratio was 3:1 and the average patient age 52.75 years (range 31–76 years). Half of the patients underwent tracheostomy for suction of secretions and the others to bypass obstructions. Two tubes (50%) were placed to manage secretions in a patient with a pontine hemorrhage and a patient with a ruptured arteriovenous malformation. One tube (25%) was placed to bypass a subglottic stenosis that developed secondary to prolonged intubation after a motorcycle accident, and one (25%) because of bilateral, true vocal fold paralysis developing after total thyroidectomy. All patients experienced sudden-onset dyspnea (100%) and two an intolerable cough (50%). The most serious presentation was cardiac arrest in one patient in a neurology ward (case 1). This was promptly detected and managed. The time to admission of the other three cases ranged from 2 h to 2 days. The most common physical feature was reduced breath sounds (50%). The dislodged tubes were in the right tracheobronchial tree, right main bronchus, and left main bronchus in two (50%), one (25%), and one (25%) patient(s), respectively. The average intubation time with the metallic tube prior to fracture was 24 days (range 3–34 days). Rigid endoscopy was used to remove the dislodged tubes in three cases (75%), and flexible endoscopy (employing a balloon catheter technique under local anesthesia) was performed in the other case. The details of all patients are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details of all patients

| No. | Age (years) | Diagnosis | Indication for TT | Type of TT | Duration of wearing TT (days) | Fracture site of outer TT | Site of dislodged part | Character of tube | Method of removal | Anesthesia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51 | Pontine hemorrhage | Suction secretion | Silver | 3 | Junction between tube and neck plate | Right tracheo bronchus | No debris | Rigid bronchoscope via stoma | GA |

| 2 | 76 | Rupture AVM | Suction secretion | Stainless | 34 | Mid shaft | Left main bronchus | Debris | Flexible bronchoscopy | LA |

| 3 | 53 | Bilateral VF paralysis | Bypass obstruction | Stainless | 29 | Mid shaft | Right tracheo bronchus | Debris | Rigid bronchoscope via stoma | GA |

| 4 | 31 | SGS secondary to prolong intubation from trauma | Bypass obstruction | Stainless | 30 | Mid shaft | Right main bronchus | Debris | Rigid bronchoscope via stoma | GA |

TT tracheostomy tube, LA local anesthesia, GA general anesthesia, AVM arteriovascular malformation, VF vocal fold, SGS subglottic stenosis

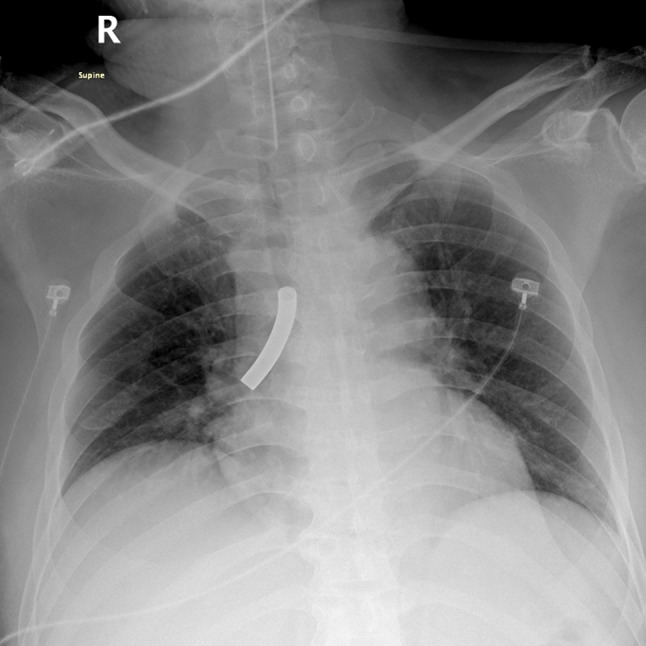

The most common signs were sudden dyspnea and a severe cough. Physical examination revealed reduced breath sounds in two cases but not the other two cases. All chest radiographs revealed dislodged tubes in the tracheobronchial tree. Rigid endoscopy was performed under general anesthesia, using a tracheostoma. The dislodged tubes were grasped with alligator forceps. One tracheostoma was revised by electrocauterization (case 1) to allow passage of the dislodged tube. The most common tube material was stainless steel (three cases; 75%). The fracture sites were the mid-shaft of the outer tube (three cases; 75%) and the junction between the outer tube and the neck plate (one case; 25%). All mid-shaft fractures had sharp edges and debris was evident inside the tubes. The fracture at the junction between the outer tube and neck plate had dull edges and lacked debris. The radiographs and the fracture tube of case 1 are shown in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively. The fracture tube of case 2 are shown in Fig. 3, respectively.

Fig. 1.

A chest radiograph showing fracture outer metallic tracheostomy tube shown in right tracheobronchus (case 1)

Fig. 2.

Photograph showing the fractured at the junction of silvers tracheostomy tube with dull edge without debris (case 1)

Fig. 3.

Photograph showing the fractured at the mid shaft of stainless tracheostomy tube with sharp edge and extensive debris (case 2)

The endoscopies were successfully removed the dislodged tubes. All of the patients were recovery to their prior status. The chest radiographs were serial monitored and returned to normal.

Discussion

A fractured tracheotomy tube presenting as a foreign body in the tracheobronchial tree is a rare complication. The first case was reported in 1960 by Bassoe and Boe [4]. Since that time, fractures of tracheotomy tubes have been reported occasionally. Atypically, we encountered four cases over 3 years. The incidence was very low, but the presentations were serious. All four patients had been intubated with metallic tubes for only short periods (3–34 days); we encountered three fractures of stainless steel tubes and one of a silver tube. The most common fracture site was the mid-shaft of the outer tube.

Today, metallic tracheostomy tubes are discarded in developed countries. Meanwhile, they are widespread used in Middle East, South and Southeast Asia. Modern metallic tracheostomy tubes are made from metal alloys containing some or all of the following materials: silver, stainless steel, nickel, copper, and zinc [5, 6]. The silver tracheostomy tube was a prototype tube that seemed free of corrosion on electron microscopic examination [7]. It was thus recommended that only pure silver tubes be placed in patients requiring long-term tracheostomy [6]. However, the literature suggested that on prolonged use, silver tubes might fracture [8]. Because of the high cost of silver tubes, modern metallic tracheostomy tubes are universally made from stainless steel and do not easily stain, corrode, or rust, unlike ordinary steel [2, 9]. In metallurgy, stainless steel can corrosion. There are numerous grades of stainless steel with varying chromium and molybdenum contents. Their corrosive resistance can increase with increasing percentage of chromium content. While, additional molybdenum increases corrosion resistance in reducing acids and against pitting attack. The advantages of metallic tubes are that they can be used for long periods and are easily maintained via repeated washing and sterilization. However, corrosion may be an issue.

The causes of metallic tube fracture include:

Prolonged wear-and-tear; aging [9];

Patient loss to tube-changing follow-up (patients did not visit us at the times when their tubes required changing) [10];

Repeated tube removal and re-insertion, associated with mechanical stress and early erosion [10];

Corrosion caused by repeated sterilization (exposure to oxygen, moisture and temperature can induce oxidation, in turn causing corrosion. Also, prolonged use creates internal stresses triggering alkali-mediated corrosion); [4, 9–11] and

We found that the most common fracture site differed from those described by others even though we had limitation of numbers [2, 9, 18, 19]. Fractures were more common at the mid-shaft of the outer tube than at the junction between the neck plate and the tube. The mid-shaft fracture sites of cases 2–4 featured extensive debris, and early corrosion and rusting. We suspect that the stainless steel was of poor quality and we discarded all tracheotomy tubes of this type. In case 1, the fracture occurred at the junction of the neck plate and the tube; we found no debris or corrosion. We suspect a manufacturing defect in the melting step. We also discarded all silver tracheostomy tubes. Today, we use only polyvinylchloride tubes instead of metallic tubes.

Fractured tracheostomy tubes in the tracheobronchial tree can trigger many complications. The most serious complication was cardiac arrest followed by airway obstruction. After brief cardiac resuscitation, the vital signs returned. We considered whether secretions had obstructed the dislodged tube, closing the airway. However, the tube was hollow and ventilation remained possible after dislodgement into the tracheobronchial tree. Although rare, a fractured tracheostomy tube should be considered during the differential diagnosis of a patient with a tube who presents with dyspnea or an intolerable cough. Tube inspection should be performed immediately to avoid a delay in diagnosis and further complications. Chest radiography assists in diagnosis and defines the position of the dislodged tube.

Rigid or flexible endoscopy can be used to access and retrieve a dislodged tube. Revision tracheostoma may be required if the original tracheostoma is small.

Medical staff should check tracheostomy tubes prior to use to identify any manufacturing defects [17]. Regular follow-up is required and tube changes should be scheduled. Also, education of patients and caregivers in terms of tube maintenance is very important. As evidently reported, alternate type of tracheostomy tube such as silicone, polyvinyl chloride, polyurethane, or a combination can also be replaced due to this complication.

Conclusion

A tracheostomy tube fracture is a rare but serious medical emergency. Patients, caregivers, and physicians must recognize fractures and act promptly. Flexible or rigid bronchoscopy via a tracheostoma can be used to remove a dislodged tube. Several mechanisms of fracture may be in play. Manufacturing defects, stagnant alkaline bronchial secretions, and repeated removal, cleaning, and boiling of the tube can cause mechanical stress and degrade the passive film that coats the tube. Medical staff should check all tubes before first use. Patient education in terms of tube maintenance, and regular check-ups, is very importance and may eliminate the problem. In term of avoidance the serious complication, other types of tracheostomy tube should also be used as alternative.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that there are no known conflict of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome. This manuscript and the data it contain have not been previously published or submitted for simultaneous consideration to this or another journal.

Ethical Approval

The Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand has approved this study by IRB No. 207/60.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Stauffer JL, Olson DE, Petty TL. Complication and consequences of endotracheal tube intubation and tracheotomy. A prospective study of 150 critically ill adult patients. Am J Med. 1981;70:65–76. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90413-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piromchai P, Lertchanaruengrit P, Vatansapt P, Ratanaanekchai T, Thanaviratananich S. Fracture metallic tracheosotmy tube in a child: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:234–237. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-4-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radpay B, Pejhan S, Dabir S, Parsa T, Radpay MZ. Fracture and aspiration of tracheostomy tube. Tanaffos. 2009;8:75–78. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassoe HH, Boe J. Broken tracheotomy tube as a foreign body. Lancet. 1960;1:1006–1007. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(60)90890-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kemper BL, Rosica N, Myers EN, Sparkman T. Inner migration of the inner cannula: an unusual foreign body. Eye Ear Nose Throat Mon. 1972;51:257–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alvi A, Zahtz GD. Fracture of a synthetic fenestrated tracheotomy tube: case report and review of the literature. Am J Otolaryngol. 1994;15:63–67. doi: 10.1016/0196-0709(94)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brockhurst PJ, Feltoe BE. Corrosion and fracture of a silver tracheotomy tube. J Laryngol Otol. 1990;104:48–49. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100114811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ming CC, Ghani SA. Fractured tracheotomy tube in the tracheobronchial tree. J Laryngol Otol. 1989;103:335–336. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100108874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parida PK, Kalaiarasi R, Gopalakrishman S, Saxena SK. Fractured and migrated tracheotomy tube in the tracheobronchial tree. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78:1472–1475. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhargava SK, Bhat N, Bhargava KB. Broken tracheostomy introducer—an unusual tracheobronchial foreign body. J Laryngol Otol. 1993;107:463–464. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100123461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynrah ZA, Goyal S, Goyal A, Lyngdoh NM, Shunyu NB, Baruah B, Dass R, Yunus M, Bhattacharyya P. Fractured tracheostomy tube as foreign body bronchus: our experience with three cases. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;7:1691–1695. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Majid AA. Fractured silver tracheostomy tube: a case report and literature review. Singap Med J. 1989;30:602–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gana PN, Takwoingi YM. Fractured tracheostomy tubes in the tracheobronchial tree of a child. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;53:45–48. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(00)00291-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srirompotong S, Kraitrakul S. Fractured inner tracheostomy tube: an unusual tracheobronchial foreign body. Srinagarind Med J. 2001;16:223–225. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krempl GA, Otto RA. Fracture at fenestration of synthetic tracheostomy tube resulting in a tracheobronchial airway foreign body. South Med J. 1999;92:526–528. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199905000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kakar PK, Saharia PS. An unusual foreign body in the tracheo-bronchial tree. J Laryngol Otol. 1972;86:1155–1157. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100076349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Momani HM, Alzaben K, Mismar A. Upper airway obstruction by a fragmented tracheostomy tube: case report and review literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;17:146–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta SL, Swaminathan S, Ramya R, Parida S. Fractured tracheostomy tube presenting as a foreign body in a paediatric patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2016 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-213963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krishnamurthy A, Vijayalakshmi R. Broken tracheostomy tube: a fractured mandate. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2012;5:97. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.93098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]