Abstract

The study aims to compare the outcomes of endonasal endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) with and without nasolacrimal stents. A prospective randomized comparative study involving fifty patients, divided into two groups of 25 patients each. Group A consists of patients who underwent endoscopic DCR with silicon stent and group B consists of patients who underwent endoscopic DCR without stent. Patients were regularly followed up at 1st week, 6th week, 10th week and at the end of 5th month postoperatively. The silicone stents were removed at 6th postoperative week. Using statistical analysis results between the two groups were compared. Post-operative improvement in nasolacrimal duct obstruction and epiphora was seen in both the groups. Age of the patients ranged from 18 to 69 years with most of the patients in the age group of 40 to 49 years (46% N = 23, 12 in group A and 11 in group B). 88% of the patients were females. (N = 44, 21 in group A and 23 in group B) and 12% were males (N = 6, 4 in group A and 2 in group B). The disease was more commonly observed on the left side with 72% of the cases (N = 36, 19 in group A and 17 in group B) and 28% (N = 14, 6 in group A and 8 in group B) on the right side. In group A, (En DCR with silicone stent) 96% of the cases were successful while 4% resulted in failure whereas in group B (En DCR without stent) 92% of the cases were successful while 8% resulted in failure. Endoscopic DCR is simple and safe method. It is minimally invasive procedure as it is a direct approach to the sac. Cosmetically it is acceptable as there is no external scar. Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy with canalicular silicone intubation for shorter duration (6 weeks) is a safe and successful procedure for the treatment of nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Close follow up immediately after surgery is needed to reduce the failure rate. Regular post-operative follow up is necessary and any defect like synechia and granulation tissue formation can be released at follow up period thus increasing the success rate. En DCR has a good success rate with and without stenting of 96% and 92% respectively.

Keywords: Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR), Silicon stent, Epiphora, Nasolacrimal duct obstruction, Comparative study, Endo DCR

Introduction

Epiphora or tearing eye is a socially and functionally bothersome symptom. Dacryocystitis, an inflammatory condition of the lacrimal sac is one of the common causes of epiphora [1]. A Dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) is a surgical procedure that aims to restore drainage of tears by bypassing an obstruction in the nasolacrimal duct through creation of a bony ostium that allows communication between the lacrimal sac and the nasal cavity[2].

Closure of the rhinostomy opening is a common factor responsible for surgical failure following endonasal endoscopic DCR. The commonest cause of surgical failure in endonasal endoscopic DCR is very high or very low mucosal incision, neo-ostium obstruction by granulation tissue, infolding of flap or development of synechiae between middle turbinate and the neo-ostium site post-operatively [3]. Several methods such as mitomycin c application to the rhinostomy opening, silicon tube intubation, suturing of the mucosal flaps have been suggested to maintain a permanent opening. Stenting has been the preferred method to prevent rhinostomy closure [4]. Silicon intubation is the most common stenting method used today for endonasal endoscopic DCR. It not only prevents closure of the rhinostomy opening but also prevents scarring and stenosis of the common canaliculus after endoscopic DCR [5].

From the previous studies there have been controversial results on whether the benefits of use of stents to improve the outcome of DCR outweighs the complications sometimes associated with the stents [4]. Silicone stent improves surgical outcomes following endonasal endoscopic DCR as claimed by some studies. On the contrary, some studies reveal that silicone stent itself is a reason for surgical failure due to granulation tissue formation and complications like punctal erosion and slitting of canaliculi [6].

There is a need of studies to conclude whether the use of stents routinely is advisable. Hence it was decided to take up this study in our hospital with a 5 months follow up.

Aims and Objective

To compare the success rates of endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy with and without silicone stents.

To study the outcome of endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy.

Methods

The study was conducted over a period of one year from April 2018 to march 2019 in the department of Otorhinolaryngology at Silchar medical college and hospital, Assam, India. Ethical clearance was taken from institutional ethical committee. Written and informed consent was obtained from the patients.

50 patients of either sex having symptoms and signs suggestive of chronic dacryocystitis and fulfilling the inclusion criteria were included in the study. Detailed assessment of the patients including thorough history and complete ophthalmic examination including sac syringing was done. Detailed clinical assessment of the nose and paranasal sinuses was carried out to rule out any obvious nasal and paranasal causes for the duct obstruction. Investigations like routine blood (Hb%, TC, DC, ESR) and urine examination, X-ray PNS, diagnostic nasal endoscopy were done. Systemic assessment and fitness for the surgery was obtained. The patients were randomly divided into two groups, i.e. group A & B. The procedure of Endoscopic DCR with bicanalicular silicone stenting was done in Group A patients, & in group B patients Endoscopic DCR was done without any stenting comprising of 25 patients each. All the patients were taken up for surgery under General Anaesthesia. Patients younger than 15 years were not included in the study. Patients were followed up for a period of 5 months.

The procedure

Position: Supine with head turned towards the right, infected eye of the patient was not draped.

Packing and Infiltration: The nasal cavity was packed with 4% Xylocaine with 1:30,000 adrenaline half an hour before the start of operation. With the help of 0° 4 mm nasal endoscope, the area of the lateral wall of the nasal cavity like atrium, uncinate process and anterior part of the middle turbinate and adjacent part of the nasal septum was infiltrated with 2% Xylocaine with 1:80,000 adrenaline (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Infiltration of the lateral nasal wall using 2% xylocaine with 1:80,000 adrenaline

I. Incision and Flap ElevationIncision was made in the lateral wall of the nose with the assistance of a sickle knife, beginning at 5 mm posterior to the insertion of the middle turbinate and 10 mm above the axilla, and then proceeding vertically downwards. The inferior limit of the flap was 10 mm anterior to the uncinate and just at the superior margin of the inferior turbinate and so posteriorly based flap elevated from maxillary bone extending up to the uncinate process (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

Incision over the lateral nasal wall for elevation of posteriorly based mucosal flap

II. Bone RemovalUsing Kerrison’s punch forceps frontal process of Maxilla was nibbled for the entire length of the lacrimal sac. The Lacrimal bone was removed and the lacrimal sac exposed from fundus to the origin of Nasolacrimal duct.

III. Incision and Marsupialization of the Lacrimal SacAt the lacrimal sac region, the bony dehiscence was felt. The assistant was asked to put pressure over the lacrimal sac and by the aid of endoscope movement of the sac was confirmed. A punctum dilator was used to dilate the punctum. A lacrimal probe was passed through the punctum and endoscopically the sac was confirmed by the tenting effect of the probe on the sac and then a sickle knife was used to open the sac vertically from top to bottom. To allow both anterior and posterior flaps to be laid open without tension, the posterior flap was released at its superior and inferior margins with Belucci scissors, and the anterior flap was released with a lacrimal mini-sickle knife. The size of rhinostome varies between 5 and 8 mm approximately. Lacrimal syringing was done to determine the patency.

IV. Flap ReinsertionThe lateral nasal wall flap elevated at the beginning was trimmed to accommodate the opened lacrimal sac. A square segment was removed from the anterior portion of the flap commensurate with the size of the opened sac. This was done using a sharp through-cutting Blakesley forceps. A ball probe was used to manipulate all flaps into their final position.

V. Lacrimal Intubation: (done only in group A patients)Silicone stent was inserted into the new rhinostomy opening through both the upper and lower canaliculi. Both ends of the silicone stents are then fastened with multiple knots in the nasal cavity. Nasal packing was done & the pack removed the subsequent day (Fig. 3)

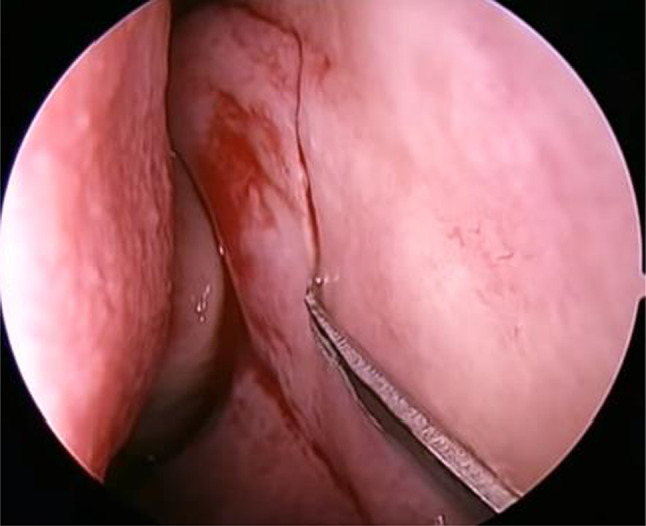

Fig. 3.

Bicanalicular silicone stent seen in the nasal cavity through the Lacrimal sac opening

Post-operative EvaluationPatients were evaluated both clinically and endoscopically for the subjective and objective relief of symptoms at 1st week, 6th week, 10th week and at the end of 5th month postoperatively.

Outcome was evaluated in terms of:

•Complete resolution of all symptoms.

•Free flow of saline on lacrimal syringing.

•Presence of a patent stoma as confirmed by nasal endoscopy (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Post operative Rhinostomy opening (left side)

Inclusion Criteria

Patients above the age of 15 years presenting with recurrent epiphora or dacryocystitis with nasolacrimal duct obstruction not fulfilling the exclusion criteria were included in the study.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients with the following conditions were excluded from the study:-

Cases of congenital dacryocystitis.

Patients with suspected presaccal obstruction including canalicular obstruction and punctual stenosis.

Coexisting nasal pathologies which could influence the outcome of the surgery like atrophic rhinitis, chronic granulomatous diseases of the nose, any nasal tumours, etc.

History of previous lacrimal surgery; failed cases.

Post traumatic and post radiation epiphora.

Immunocompromised patients, uncontrolled systemic diseases.

Unwillingness for endoscopic surgery and those not fit for anaesthesia.

Patients younger than 15 years of age.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of the study was done using the software Graphpad prism 8 for windows.

Results

50 consecutive patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria underwent endonasal endoscopic DCR with and without silicon stents between April 2018 to March 2019. The following are the findings in the study:

Age Distribution

Age of the patients ranged from 18 to 69 years with most of the patients in the age group of 40 to 49 years (46% N = 23, 12 in group A and 11 in group B). The overall mean age of presentation was 42.38 years (Tables 1, 2 and Fig. 5).

Table 1.

Age distribution in both the groups

| Age in years | Group A | Group B | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| 10–19 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| 20–29 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 5 | 10 |

| 30–39 | 5 | 20 | 3 | 12 | 8 | 16 |

| 40–49 | 12 | 48 | 11 | 44 | 23 | 46 |

| 50–59 | 5 | 20 | 5 | 20 | 10 | 20 |

| 60–70 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

Table 2.

Mean age and standard deviation in both the groups

| Group A | Group B | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 43.56 ± 11.4 | 41.2 ± 11.6 |

Fig. 5.

Scatter chart showing the age distribution in both the groups

Sex Incidence

In our study 88% of the patients were females. (N = 44, 21 in group A and 23 in group B) and 12% were males (N = 6, 4 in group A and 2 in group B) (Table 3)

Table 3.

Sex incidence

| Sex | Group A | Group B | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of males | 4 (16%) | 2 (8%) | 6 (12%) |

| No. of females | 21 (84%) | 23 (92%) | 44 (88%) |

Laterality

The disease was more commonly observed on the left side with 72% of the cases (N = 36, 19 in group A and 17 in group B) and 28% (N = 14, 6 in group A and 8 in group B) on the right side (Table 4)

Table 4.

Laterality

| Side | Group A | Group B | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Right | 6 | 24 | 8 | 32 | 14 | 28 |

| Left | 19 | 76 | 17 | 68 | 36 | 72 |

Mode of Presentation

Majority of the patients presented with chronic dacryocystitis (N = 43, 86%) and 8% (N = 4, 2 in group A,2 in group B) presented with mucocele and 6% (N = 3, 2 in group A, 1 in group B) presented with pyocele.

Chi-square test p = 0.836 NS, the presence of pyocele or mucocele did not affect the results.

Ancillary procedures

In our study, along with the standard EnDCR, 8 patients (16%) underwent Septoplasty for DNS, ( 3 in group A, 5 in group B) and 1 patient in group A underwent Turbinoplasty for inferior turbinate hypertrophy.

Fishers exact test p = 0.444 NS, the ancillary procedures did not affect the final result.

Post-Operative Period

(a) Objective Assessment

During the follow up period objective analysis was done by syringing in all the patients.

At 1st week: Syringing in group B patients was found to be patent in 92% (N = 23) and non-patent in 8% of the cases (N = 2). Syringing was not done in group A patients due to the presence of the stent (Table 5)

Table 5.

Post-operative assessment

| SYR | 1st week | 6th week | 10th week | 5th month | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | Groups | Groups | Groups | |||||

| A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | |

| Objective Assessment | ||||||||

| P | 0 |

23 (92%) |

25 (100%) |

23 (92%) |

24 (96%) |

23 (92%) |

24 (96%) |

23 (92%) |

| NP | 0 |

2 (8%) |

0 |

2 (8%) |

1 (4%) |

2 (8%) |

1 (4%) |

2 (8%) |

| Subjective Assessment | ||||||||

| SR | 1st week | 6th week | 10th week | 5th Month | ||||

| Groups | Groups | Groups | Groups | |||||

| A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | |

| R | 0 |

23 (92%) |

25 (100%) |

23 (92%) |

24 (96%) |

23 (92%) |

24 (96%) |

23 (92%) |

| NR | 0 |

2 (8%) |

0 |

2 (8%) |

1 (4%) |

2 (8%) |

1 (4%) |

2 (8%) |

SYR Syringing, P Patent, NP Not Patent, SR Symptomatic relief, R Relieved, NR Not relieved

At 6th week: In group A patients, syringing was patent in all the cases (N = 25, 100%). In group B patients, syringing was patent in 92% (N = 23) and non-patent in 8% (N = 2) of the cases (Table 5)

At 10th week: Syringing in group A was patent in 96% (N = 24) and non-patent in 4% of the cases (N = 1). In group B syringing was patent in 92% (N = 23) and was non patent in 8% of the cases (N = 2) (Table 5)

(b) Subjective Assessment

At 1st week: In group B, 92% of the patients (N = 23) reported a complete symptomatic relief, however in 8% of the case (N = 2) no relief of symptom was reported. Symptomatic assessment for group A during the first week follow up could not be assessed due to the presence of the stent (Table 5)

At 6th week: In group A, during the 6th week of follow up 100% (N = 25) of cases reported complete relief of symptom. In group B complete relief was reported by 92% (N = 23) of cases and in 8% (N = 2) there was no relief of symptom (Table 5)

At 10th week: Complete relief of symptom was reported by 96% (N = 24) of patients in group A and in 4% (N = 1) there was no relief of symptom. In group B, 92% (N = 23) of patients reported complete relief of symptom while in 8% (N = 2) there was no relief of symptom (Table 5)

Overall Result

Group A: Out of the total 25 patients who underwent En DCR with silicone stent 96% of the cases were successful while 4% resulted in failure (Table 6)

Table 6.

Overall result

| Results | Group A | Group B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | % | Cases | % | |

| Success | 24 | 96% | 23 | 92% |

| Failure | 1 | 4% | 2 | 8% |

| Chi-square test value p = 0.372, p > 0.05 is statistically not significant | ||||

Group B: Out of the total 25 patients who underwent En DCR without stent 92% of the cases were successful while 8% resulted in failure (Table 6)

Complications

(a) Intra Operative

There were no major surgical complications in our study. Intra-operatively 2 patients in group A had punctal trauma and in 1 patient there was difficulty in stent intubation. (Fisher's exact test, p > 0.999, Not significant) (Table 7).

Table 7.

Complications (Intra-operative)

| Complications | Group A | Group B |

|---|---|---|

| Punctal Trauma | 2 | 0 |

| Difficult stent Intubation | 1 | 0 |

(b) Post-Operative

Post-operatively in group A, 3 patients had minor complications which were Lid edema, prolapse of stent and Granulation Tissue formation. In group B, 2 cases of synechia, 2 cases of Rhinostomy closure and 2 cases of minor post-operative bleed was observed. (Chi square test, p = 0.1091, Not significant) (Table 8).

Table 8.

Complications (Post-operative)

| Complications | Group A | Group B |

|---|---|---|

| Lid Edema | 1 | 0 |

| Prolapse of stent | 1 | 0 |

| Granulation tissue formation | 1 | 0 |

| Synechia | 0 | 2 |

| Rhinostomy closure | 0 | 2 |

| Minor bleed | 0 | 2 |

Discussion

A total number of 50 Cases of chronic dacryocystitis who qualified our inclusion criteria underwent Endo DCR with and without silicon stenting and were evaluated in our present study. The following observations were noted during the course of our study:

(a) Age Incidence

Age of the patients ranged from 18 to 69 years with most of the patients in the age group of 40 to 49 years (46% N = 23, 12 in group A and 11 in group B), which is similar to the findings of H.Basil Jacobs (1959) where he found that the maximum incidence of this condition is between 40–55 years of age [7]. Duke Elder found that the disease preferentially affects adults over middle age, being relatively rare in children and adolescents. The highest incidence quoted by him was in the 4th decade of life [8].

(b) Sex Incidence

The disease was predominantly seen in females (88%). In a study done by H.Basil Jacobs (1959), female to male ratio of 3:1 was found in his series of patients. He found that females were more affected by chronic dacryocystitis as they had a higher vascular congestive factor and a narrower bony canal [7].

Chronic dacryostitis is observed to be common in women of low socio-economic group. It might be due to their bad personal habits, long duration of exposure to smoke in kitchen and dust in external environment. Other possible cause could be congenital anatomical narrowing of nasolacrimal drainage system in females as compared to males[9].

(c) Laterality

Most of the cases presented with the disease on the left side accounting for 72% of the total cases (N = 36, 19 in group A and 17 in group B) and 28% (N = 14, 6 in group A and 8 in group B) had disease on the right side, hence showing that left side is more commonly affected than the right side.

It is observed that nasolacrimal duct and lacrimal sac formed a greater angle on right side than left side [10]. It increases the chance of stasis and obstruction of nasolacrimal duct and lacrimal sac on left side. It is, therefore, attributed as the cause for preponderance of chronic dacryocystitis on the left side (Arisi 1960).

(d) Mode of Presentation

In our study majority of the patients presented with chronic dacryocystitis 86%, 8% presented with mucocele and 6% presented with pyocele. Epiphora was present in all the patients and it is consistent with other studies [11–14].

(e) Associated Rhinological Conditions

In our study, Deviated nasal septum is by far the commonest rhinological condition associated with dacryocystitis accounting for 16% of the cases which is similar to the findings of Mallampalli et al. [15]. In another study done by Arun Kumar et al. [16] DNS was seen in 12% of cases which is consistent with our finding.

Along with the standard En DCR, 8 patients (16%) underwent Septoplasty for DNS, and 1 patient underwent Turbinoplasty for inferior turbinate hypertrophy. Associated rhinological conditions did not affect the results in our study which similar to other studies [15, 16].

(f) Results of our Study in Comparison with other Studies

| Study | No. of cases | Follow up (months) | With stent (%) | Without stent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harugop et al. (2008) | 50 | 16.3 | 96 | 93 |

| Smirnov et al. (2008) | 23 | 6 | 78 | 100 |

| Kakkar et al. (2008) | 20 | 2.5 | 85 | 90 |

| Unlu et al. (2009) | 19 | 9.7 | 84 | 94.7 |

| Shashidhar et al. (2014) | 32 | 6 | 93 | 86.7 |

| Reddy et al. (2015) | 10 | 6 | 90 | 80 |

| Fayers et al. (2016) | 152 | 12 | 94.7 | 87.8 |

| Rao et al. (2016) | 25 | 6 | 92 | 84 |

| Ahmad et al. (2016) | 15 | 12 | 93 | 86.6 |

| Smitha et al. (2016) | 30 | 6 | 85 | 90 |

| Chong et al. (2013) | 63 | 12 | 96 | 95.3 |

| Al-Qahtani et al. (2012) | 92 | 12 | 96 | 91 |

| Our present study | 50 | 5 | 96 | 92 |

In our study the success rates of En DCR with and without silicone stenting is 96% and 92% respectively. Overall complete symptomatic relief was seen in 47 (94%) cases, & 3 (6%) reported no symptomatic relief out of the total 50 cases. (1 in group A and 2 in group B).

Silicone stenting was first introduced in the 1950s for external DCR and the 1960s for endoscopic DCR [17, 18]. Thereafter, stents rapidly became favored by surgeons who perform lacrimal surgery.

Many variations of endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy with little modifications like the use of stents, laser and mitomycin-C have been described in the last decade, with equally good results. A bicanalicular silicone tube is the stent most often used in DCR procedures to prevent obliteration of the rhinostomy opening after DCR.

Although Epiphora resolution rate was more in stent group but it was not statistically significant which is in concordance with Acharya et al. [19], Harvinder et al. [20]and Feng et al. [21] studies. Also Kakkar et al. [22] and Unlu et al. [23] did not find any significant differences between silicon stent DCR and conventional DCR. Dortzbach et al. [24] reported that using silicon tubes in children is associated with complications.

In a recently published study done by Moscato et al. [25] it was found that silicone intubation has good, long-term success for relief of epiphora in patients with presumed functional NLDO. Claudio A.C et al. [26] advocate a selective stenting approach, to reserve stenting for cases with tight common canaliculus opening as noted in surgery, and in treating failures. Thus, the success rate with stent in our study is 96% which is found to correlate well with studies of Weidenbacker et al. [27], Zhou et al. [28],Yung et al. [29], Bambule et al. [30], PJ Wormland et al. [31]. The procedure was a failure in 4% (N = 1) in group A due to granulation tissue formation around the stent.

In our study, the stent was removed on the 6th post operative week. In a meta analysis done by Min Gyu Kang et al. from 2007 to 2016, it was found that the optimal duration of silicone stenting is controversial, with the reported duration ranging from 4 weeks to 4 months [4, 32, 33].

Most of the study suggests that the stent has to be kept for approximately 3 months, removal before this time is often the cause of failure. Granulation tissue may be detected after 3 months of stenting [34–36] but we suggest keeping the stent for 6 weeks postoperatively to prevent complications like granulations, slitting of canaliculi and punctual erosion, fibrosis, and with good success rates of 96%, which is comparable with other studies.

The success rate in group B without stent is 92%. 23 patients reported a complete symptom relief and 2 cases reported no relief in the symptoms. The procedure was a failure in 8% (N = 2) cases. Closure of the rhinostomal opening was seen in both the cases which led to failure. Similarly, Ressionitis et al. [37] found obstruction of neo-ostium by granulation tissue or fibrosis as the most common cause of failure. Adhesion may also form between the flaps of nasal mucosa, flaps of lacrimal sac and sometimes between the nasal mucosa at the margins of ostium and nasal septum if there is damage to the nasal mucosa covering the nasal septum [37].

S.H.Mohamad et al.[38] reported that DCR without a stent has the advantage of a shortened operative time as well as avoidance of the complications associated with stents and the inconvenience to the patient of having the stents removed.

During our study no major complications were observed. Post-operatively in group A, 3 patients had minor complications which were Lid edema, prolapse of stent and Granulation Tissue formation. In group B, 2 cases of synechia, 2 cases of Rhinostomy closure and 2 cases of minor post operative bleed was observed. In none of the patients was the stent needed to be removed before 6 weeks. The silicone stenting material did not cause either punctal stenosis or canalicular laceration in any of the cases.

In a recent meta analysis study done by Min Gyu Kang et al. [4] it was found that common complications after endoscopic DCR included synechia, granulation tissue formation, postoperative bleeding, and other complications associated with the silicone tube, including discomfort from stenting, stent extrusion, difficulty in stent removal, and punctal laceration. They concluded that there was no significant difference in the surgical complication rate between endoscopic DCR with silicone intubation and that without silicone intubation, suggesting that the use of silicone stents does not increase the risk of synechia, granulation tissue formation, and postoperative bleeding which is similar to the findings in our study.

Conclusion

In the present study, we compared the results of En DCR with and without stenting in 50 cases of chronic dacryocystitis where silicone material was used as stent in 50% of the randomly divided cases. Based on the available data and from literature, we conclude that:

Endoscopic DCR is simple and safe method.

It is minimally invasive procedure as it is a direct approach to the sac.

Can be performed safely in cases of pyocele and mucocele.

Cosmetically it is acceptable as there is no external scar.

Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy with canalicular silicone intubation for shorter duration (6 weeks) is a safe and successful procedure for the treatment of NLDO.

Nasal and paranasal pathology can be corrected at the same sitting.

Close follow up immediately after surgery is needed to reduce the failure rate.

Regular post-operative follow up is necessary and any defect like synechia and granulation tissue formation can be released at follow up period thus increasing the success rate.

En DCR has a good success rate with and without stenting of 96% and 92% respectively.

Funding

No funding sources.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kumar D. Lacrimal sac infections and microbial analysis. TNOA J Ophthalmic Sci Res. 2017;55(4):293–297. doi: 10.4103/tjosr.tjosr_23_18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jawaheer L, MacEwen CJ, Anijeet D (2017). Endonasal versus external dacryocystorhinostomy for nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Prakash M, Viswanatha B, Rasika R. Powered endoscopic endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy with mucosal flaps and trimming of anterior end of middle turbinate. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;67(4):333–7. doi: 10.1007/s12070-014-0807-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang MG, Shim WS, Shin DK, Kim JY, Lee J-E, Jung HJ. A systematic review of benefit of silicone intubation in endoscopic Dacryocystorhinostomy. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;11(2):81–88. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2018.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim DH, Kim SI, Jin HJ, Kim S, Hwang SH. The Clinical Efficacy of silicone stents for endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy: a meta-analysis. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;11(3):151–157. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2017.01781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jyothi A, Kumar A, Chiluveru P. Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy: our experience. Int J Contemporary Surg. 2016;2(4):254–257. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobs HB. Symptomatic epiphora. British J Ophthalmol. 1959;43(7):415. doi: 10.1136/bjo.43.7.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duke Elder S MPA. Diseases of lacrimal passages. Chapter X. In: The Ocular Adnexa in System of Ophthalmology, Duke Elder S (ed). St. Louis: C V Mosby Company. 1974:675–773.

- 9.Naik S, Naik S. Comparative study of prolene wire stent & silicon tube stent used in 150 cases of endonasal dacryocystorhinostomies. Pakistan J Otolaryngol. 2011;27:42–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sood NN, Ratnaraj A, Balaraman G, Madhavan HN. Chronic dacryocystitis-a clinico-bacteriological study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1967;15(3):107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh M, Jain V, Gupta SC, Singh SP. Intranasal endoscopic DCR (END-DCR) in cases of dacryocystitis. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;56(3):177–183. doi: 10.1007/BF02974345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brook I, Frazier EH. Aerobic and anaerobic microbiology of dacryocystitis. American J Ophthalmol. 1998;125(4):552–554. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)80198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vishwakarma R, Singh N, Ghosh R. A study of 272 cases of endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;56(4):259–261. doi: 10.1007/BF02974382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sprekelsen MB, Barberan MT. Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy: surgical technique and results. Laryngoscope. 1996;106(2):187–189. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199602000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mallampalli VB, Erra R. A CLINICAL AND BACTERIOLOGICAL STUDY OF CHRONIC DACRYOCYSTITIS.

- 16.Arun Kumar BKR. Post operative outcomes in endonasal dacrocystorhinostomy. MedPulse Int J ENT, Print ISSN. 2018;6(1):2579–854. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fayers T, Dolman PJJO. Bicanalicular silicone stents in endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy: results of a randomized clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(10):2255–2259. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madge SN, Selva D. Intubation in routine dacryocystorhinostomy: why we do what we do. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2009;37(6):620–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2009.02094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acharya K, Pradhan B, Thapa N, Khanal S. Comparison of outcome following endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy with external dacryocystorhinostomy. Nepalese J ENT Head Neck Surg. 2011;2(2):2–3. doi: 10.3126/njenthns.v2i2.6791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gurdeep S. Powered endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy with mucosal flaps without stenting. Med J Malaysia. 2008;63(3):237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng Y-f, Cai J-q, Zhang J-y, X-hJCjoo H. A meta-analysis of primary dacryocystorhinostomy with and without silicone intubation. Canadian J Ophthalmol. 2011;46(6):521–527. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kakar V CJ, Sachdeva S, Sharma N. Ramesh. Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy with and without silicone stent: A comparative study. Internet J Otorhinolaryngol. 2009; 9:1.

- 23.Unlu HH, Aslan A, Toprak B, Guler C. Comparison of surgical outcomes in primary endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy with and without silicone intubation. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;111(8):704–709. doi: 10.1177/000348940211100809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dortzbach RK, France TD, Kushner BJ, Gonnering RS. Silicone intubation for obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct in children. American J Ophthalmol. 1982;94(5):585–590. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(82)90001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moscato EE, Dolmetsch AM, Silkiss RZ, Seiff SR. Silicone intubation for the treatment of epiphora in adults with presumed functional nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Ophthalmic Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2012;28(1):35–39. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e318230b110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Callejas CA, Tewfik MA, Wormald PJ. Powered endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy with selective stenting. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(7):1449–1452. doi: 10.1002/lary.20916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weidenbecher M, Hosemann W, Buhr W. Endoscopic endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy: results in 56 patients. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1994;103(51):363–367. doi: 10.1177/000348949410300505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou W, Zhou M, Li Z, Wang T. Endoscopic Intranasal dacryocystorhinostomy in forty-five patients. Chinese Med J. 1996;109(10):747–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yung MW, Hardman-Lea S. Endoscopic inferior dacryocystorhinostomy. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1998;23(2):152–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1998.00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bambule G, Chamero J. Endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) Revue medicale de la Suisse romande. 2001;121(10):747–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wormald PJJTL. Powered endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy. 2002;112(1):69–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Al-Qahtani AS. Primary endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy with or without silicone tubing: a prospective randomized study. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26(4):332–334. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2012.26.3789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yeon JY, Shim WS. Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy without silicone stent. Acta Otolaryngol. 2012;132(Suppl 1):S77–81. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2012.659754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Machín JS, Laguarta JC, Ariza MDG, Medrano J, Bescós JC. Lacrimal duct obstruction treated with lacrimonasal stent. Archivos de la Sociedad Espanola de Oftalmologia. 2003;78(6):315–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bogdănici C, Lupaşcu C, Halunga M. Complications after catheterization of nasolacrimal duct. Oftalmologia. 2002;55(4):39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beloglazov VG, At'kova EL, Malaeva LV, Nikol'skaia GM, Azibekian AB. Intubation granulomas of the lacrimal ducts in patients with silicone implants. Vestnik oftalmologii. 1998;114(5):29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ressiniotis T, Voros GM, Kostakis VT, Carrie S, Neoh C. Clinical outcome of endonasal KTP laser assisted dacryocystorhinostomy. BMC Ophthalmol. 2005;5:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohamad SH, Khan I, Shakeel M, Nandapalan V. Long-term results of endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy with and without stenting. Ann Royal College Surgeons England. 2013;95(3):196–199. doi: 10.1308/003588413X13511609957939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]