Abstract

The relationship between temporal bone pneumatization (TBP) pattern and sinus mucous thickness grading on computed tomography scans of paranasal sinuses was investigated. In this cross-sectional study, a total of 200 temporal bones and paranasal sinuses were evaluated in CT scans of 100 patients with chronic sinusitis (CRS). The mucosal thickness of paranasal sinuses was classified into two groups (0–6 and 7–12) according to the Lund-Mackay (LM) staging system. Also, pneumatization patterns of petrous apex and perilabyrinthine regions were classified according to Jadvah et al. method. Data were analyzed using Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. The most common pneumatization pattern in the petrous apex was pattern A (49.5%) and in the perilabyrinthine region was pattern B (50%). In the petrous apex, the highest frequencies of pattern A (51.7%) and pattern C (24.6%), among other pneumatization patterns, were found in score range of 7–12 and 0–6, respectively, which was statistically significant (P = 0.017). Although in the perilabyrinthine region, the highest frequencies of pattern A (24.1%) and pattern C (32.7%) were in LM score ranges of 7–12 and 0–6, respectively, no significant difference was found (P = 0.589). The petrous apex pneumatization decreases with an increase in the severity of CRS, which can be in response to the eustachian tube dysfunction and common pathogens with CRS. A similar relationship was also found in the perilabyrinthine region, although it was not statistically significant. No significant relationship between TBP and severity of CRS was found in the age and sex groups.

Keywords: Computed tomography, spiral, Sinusitis, Temporal bone

Introduction

Temporal bone pneumatization (TBP) is the process by which the epithelium infiltrates the developing bone, forming epithelial-lined air cells. Some of the proposed functions of temporal bone air cells include sound resonance, skull weight loss, impact protection, and air supply for the middle ear to compensate for changes in the Eustachian tube function [1]. There are different classifications for evaluating TBP patterns [2, 3], including the one proposed by Jadvah et al. [4], in which the petrous segment of internal carotid canal and the superior semicircular canal were used as the references structures to classify TBP in the petrous apex and perilabyrinthine regions.

Several factors, such as environmental factors, genetic and infectious diseases affect TBP [5]. Also, factors, including age and pathological lesions in the Eustachian tube and the middle ear, can cause sclerosis in the mastoid segment of the temporal bone and reduce pneumatization over time [6–8].

Evidence suggests that positive pressure on the nasopharynx through the Eustachian tube, along with the total nasal airflow, can influence the development of temporal bone air cells [9]. According to this,Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) that is a clinical syndrome associated with permanent inflammation of nasal mucosa and paranasal sinuses [10], influences TBP by disrupting the Eustachian tube function and nasal air flow [11, 12].

A simple method for grading the severity of CRS is to score the mucosal thickness of paranasal sinuses radiologically, using Lund-Mackay (LM) staging system. [13] The relationship between TBP and CRS patterns was investigated in part of the study by Al-Esawi et al. [3] studying the relationship between temporal bone hyperphenomenatis and tinnitus, as well as a study by Seifert et al. [2] evaluating the relationship between TBP and development of paranasal sinuses in patients with cystic fibrosis. However, these studies provide limited information regarding the association between TBP patterns and CRS severity. Considering the importance of determining the effects of sinus diseases on the temporal bone and middle ears, this study was specifically designed to examine the relationship between TBP pattern and sinus mucosal thickness grading on the computed tomography (CT) scans of paranasal sinuses.

Materials and Methods

In this cross-sectional study, CT scans of paranasal sinuses were examined in 100 patients with the clinical symptoms of chronic sinusitis from 2017 to 2019. A total of 200 temporal bones and paranasal sinuses were evaluated. The ethics approval number for this study was IR. GUMS.REC.1397.248.The CT scans were acquired using spiral CT machine (Siemens CT machine, Siemens, Philadelphia, USA) and ( Philips CT machine, Philadelphia, USA) devices in 16 slices and with relative exposure conditions of 110 KVP and 147 mAS. We had informed consent of the patients to use from their CT data.

The inclusion criteria in this study were as follows:

Age > 18 years and < 55 years.

CT scans depicting the external ear, middle ear, and perilabyrinthine and petrous apex regions

On the other hand, the exclusion criteria were:

Radiographic evidence of sinus surgery, ear surgery, or paranasal/nasopharynx lesions.

Low-quality CT scans (e.g., motion blurring).

Images without a bone window.

CT scans were studied in medical archive systems (PACS, PACS PLUS, Gyeonggi-do, South Korea) and (PACS, MARCO PACS, Tehran, Iran) viewers. The image thickness was 1 mm in axial images and 2 mm in reconstructed coronal images.

Scan Analysis of Paranasal Sinuses

The reconstructed axial and coronal sections were used to evaluate the paranasal sinuses, as well as the osteomeatal complex.

There are several systems for grading CRS severity, including the Lund-Mackay (LM) staging system, which is widely used for its simplicity. This scale includes radiographic, clinical and endoscopic scoring. Generally, radiological grading is the most extensively used measure of this scale [13].

In radiological LM grading, three scores (0 = no abnormalities, 1 = partial opacification, and 2 = complete opacification) were assigned to each sinus (frontal, anterior ethmoid, posterior ethmoid, maxillary, and sphenoid), and two scores were assigned to the osteomeatal complex (0 = not obstructed; 2 = obstructed). The total score for each side was calculated separately (0–12). Also, the total score was divided into two groups (0–6 and 7–12), according to a study by Ashraf et al. [14].

Scan Analysis for Temporal Bone Pneumatization

This study followed the method of Jadvah et al. [4] in the petrous apex and perilabyrinthine regions to evaluate TBP. To see the greatest area of pneumatization, The Z axis was set up in a manner that malleoincudal complex appeared as an ice-cream-cone-shaped structure on axial images.

Petrous Apex Penumatization

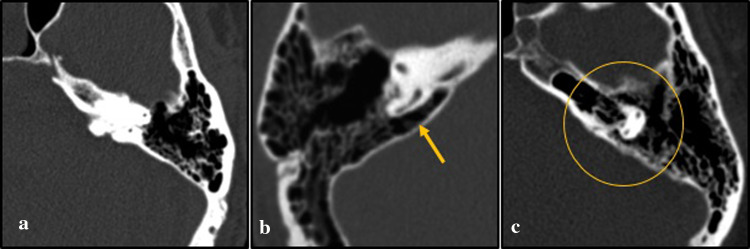

Petrous segment of internal carotid canal in the axial sections was used to classify TBP in the petrous apex as follows (Fig. 1):

-

A.

No pneumatization of the petrous apex. (a)

-

B.

Small numbers of aircells on either side (medial or lateral) of the carotid canal. (b)

-

C.

Pneumatization is surrounding the carotid canal. (c)

Fig. 1.

a–c Axial CT images reveal patterns of petrous apex pneumatization. “cc” refers to the carotid canal, arrow and circle show the area of penumatization

Perilabyrinthine Pneumatization

Perilabyrinthine pneumatization around the superior semicircular canal in the axial sections was classified as follows (Fig. 2):

-

A.

There is no evidence of pneumatization in the inner ear region.(a)

-

B.

Pneumatization can be seen in the medial or lateral parts of the superior semicircular canal.(b)

-

C.

Pneumatization completely surrounds the superior semicircular canal.(c)

Fig. 2.

a–c Axial CT images reveal patterns of Perilabyrinthine pneumatization. Arrow and circle show the area of penumatization

CT scans were investigated for LM grading and TBP evaluation on different days. The collected information was read independently by two maxillofacial radiologists. The two examiners discussed their disagreements and reached a consensus.

Statistical Analysis

Finally, information related to TBP grading in two petrous apex and perilabyrinthine regions was evaluated in SPSS version 24 (Chicago, IL, USA). Data were classified into two groups in terms of age (18–39 and 40–55 years) and sex (female and male). To compare the frequency of TBP patterns in different grades of LM, Chi-square and Fisher's exact tests were used. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In this cross-sectional study, CT scans of paranasal sinuses were studied in 100 patients, including 46 females (46%) and 54 males (54%), with the mean age of 38.37 ± 11.08 years (range, 19–56 years). A total of 200 temporal bones and paranasal sinuses were evaluated.

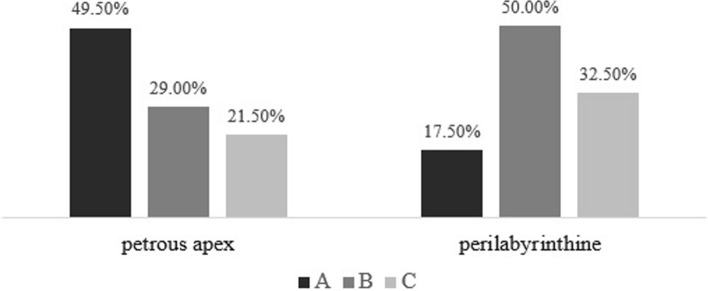

Pneumatization Patterns in the Petrous Apex and Perilabyrinthine Regions

The most common pneumatization pattern in the petrous apex was pattern A (49.5%; no pneumatization around the carotid canal). On the other hand, the most common pneumatization pattern in the perilabyrinthine region was pattern B (50%; pneumatization in the medial or lateral parts of the superior canal) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Frequency of petrous apex and perilabyrinthine pneumatization patterns

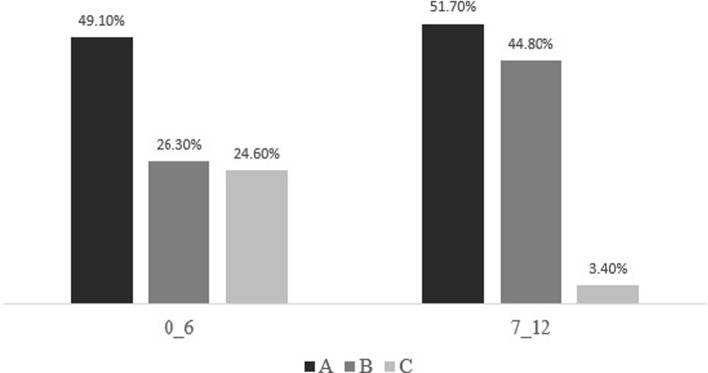

Pneumatization Patterns of the Petrous Apex in Two LM groups

Figure 4 represents the frequency percentage of petrous apex pneumatization patterns, in two LM groups. Among pneumatization patterns, pattern A (51.7%) and pattern B (44.8%) showed the highest frequencies percentage in the petrous apex in the LM score range of 7–12. On the other hand, the highest frequency percentage of pattern C in the petrous apex (24.6%) was found in the LM score range of 0–6. The results of Chi-square test showed that the difference between the groups was significant (P = 0.017).

Fig. 4.

Frequency of petrous apex pneumatization patterns, in two LM groups

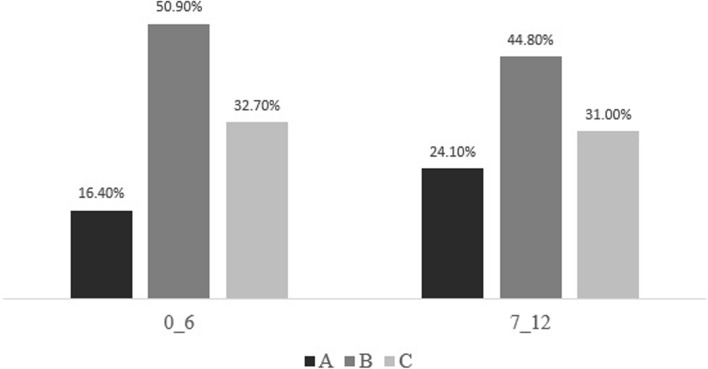

Perilabyrinthine pneumatization patterns in two LM groups

As shown in Fig. 5, the highest percentage frequency of pneumatization pattern A in the perilabyrinthine region (24.1%) was found in the LM score range of 7–12, while the highest frequencies percentage of pattern B (50.9%) and pattern C (32.7%) were found in the LM score range of 0–6. However, Chi-square test showed no significant difference between the groups (P = 0.589).

Fig. 5.

Frequency of petrous apex pneumatization patterns, in two LM groups

Pneumatization Patterns of the Petrous Apex and Perilabyrinthine Regions in Two LM Groups According to Age

In the age group of 18–39 years, the highest frequency percentage of pneumatization pattern A (57.1%) and pattern B (38.1%) in the petrous apex, as well as the highest frequency of pattern A (19%) and pattern B (52.4%) in the perilabyrinthine region, was found in the LM score range of 7–12. Also, the highest frequency of pneumatization pattern C in the petrous apex (25.3%) and perilabyrinthine (39.4%) regions was reported in the LM group of 0–6. According to the Fisher's exact test, there was no significant difference between the petrous apex and perilabyrinthine pneumatization patterns in the two LM groups in this age group (P = 0.101 and P = 0.695, respectively).

In the age group of 40–55 years, the highest frequency percentage of pneumatization pattern A (51.4%), pattern B (62.5%), and pattern C (23.6%), among other pneumatization patterns in the petrous apex, was found in the LM score range of 0–6, 7–12, and 0–6, respectively. However, Fisher's exact test showed no significant difference in this age group (P = 0.071). With regard to the perilabyrinthine pneumatization in this age group, the highest frequencies of pattern A (37.5%), pattern B (61.1%), and pattern C (37.5%), among other pneumatization patterns, were found in the LM score ranges of 7–12, 0–6, and 7–12, respectively. Nevertheless, Fisher's exact test did not show any significant differences in this age group (P = 0.078).

Pneumatization Patterns of the Petrous Apex and Perilabyrinthine Regions in the Two LM Groups According to Gender

The frequency of pneumatization patterns in the petrous apex and perilabyrinthine regions, in the two LM groups according to sex, is presented in Tables 1 and 2. Fisher's exact test showed no significant difference between the petrous apex and perilabyrinthine pneumatization patterns in the two LM groups in terms of sex.

Table 1.

Frequency of pneumatization patterns in the petrous apex in the two LM groups according to gender

| Gender | Petrous apex penumatization pattern | Total | P value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A N(%) |

B N(%) |

C N(%) |

|||||

| Female | Lund-Mackay scoring | 0–6 |

40 50.0% |

20 25.0% |

20 25.0% |

80 100.0% |

0.129 |

| 7–12 |

8 66.7% |

4 33.3% |

0 0.0% |

12 100.0% |

|||

| Total |

48 52.2% |

24 26.1% |

20 21.7% |

92 100.0% |

|||

| Male | Lund-Mackay scoring | 0–6 |

44 48.4% |

25 27.5% |

22 24.2% |

91 100.0% |

0.068 |

| 7–12 |

7 41.2% |

9 52.9% |

1 5.9% |

17 100.0% |

|||

| Total |

51 47.2% |

34 31.5% |

23 21.3% |

108 100.0% |

|||

*P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

Table 2.

Frequency of pneumatization patterns in the perilabyrinthine regions in the two LM groups according to gender

| Gender | Perilabyrinthine penumatization pattern | Total | P value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A N(%) |

B N(%) |

C N(%) |

|||||

| Female | Lund-Mackay scoring | 0–6 |

14 17.5% |

37 46.3% |

29 36.3% |

80 100.0% |

.425 |

| 7–12 |

4 33.3% |

4 33.3% |

4 33.3% |

12 100.0% |

|||

| Total |

18 19.6% |

41 44.6% |

33 35.9% |

92 100.0% |

|||

| Male | Lund-Mackay scoring | 0–6 |

14 15.4% |

50 54.9% |

27 29.7% |

91 100.0% |

1.000 |

| 7–12 |

3 17.6% |

9 52.9% |

5 29.4% |

17 100.0% |

|||

| Total |

17 15.7% |

59 54.6% |

32 29.6% |

108 100.0% |

|||

*P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

Discussion

TBP is the process by which the epithelium infiltrates the developing bone, forming epithelial-lined air cells [11]. It seems that the total nasal airflow and positive pressure on the nasopharynx through the Eustachian tube influence the development of temporal bone air cells [9]. The Eustachian tube is connected to the middle ear through its lateral end and also communicate directly with the petrous apex through peritubal air cells [15]. In this regard, a study by Jadvah et al. [4] showed that there is a significant relationship between TBP grade and presence of peritubal cells.

It has been shown that the process of TBP is completed in women by the age of 10 years and in men by the age of 15 years [11]. On the other hand, Park et al. [6] showed that with advancing age, pneumatization of the mastoid segment of the temporal bone gradually decreases until the seventh decade of life, whereas it follows a rapid decline after this age. These results are similar to those reported by Cinamon et al. [7], who examined the pneumatization of the mastoid segment in adults. Also, in another study, Lee et al. [8] showed that pathological lesions in the middle ear and Eustachian tube cause sclerosis in the mastoid part of the temporal bone, and pneumatization reduces during the period of life older than the period of previous study.

Since CRS, a clinical syndrome associated with permanent inflammation of nasal mucosa and paranasal sinuses, can affect TBP through Eustachian tube dysfunction, in the present study, we examined the relationship between TBP pattern and sinus mucosal thickness grading on CT scans of paranasal sinuses.

Ashraf et al. [14] evaluated a total of 199 patients with the mean age of 47.1 years, without a history of chronic sinusitis. The mean LM score was 4.26 in healthy individuals, which was significantly different from the score expected in healthy cases (score 0). Therefore, an LM score ≥ 5 in individuals without a history of chronic sinusitis can be considered normal; this criterion should be considered, besides clinical findings, in patients with CRS, and also LM score ≥ 6 is a strong radiologic evidence of CRS [14]. In the present study, LM scores were divided into two groups (0–6 and 7–12). It was assumed that subjects with LM scores of 7–12 have strong radiological evidence for CRS.

In the present study, the most common pneumatization pattern in the petrous apex, was pattern A (no pneumatization around the carotid canal) in all LM groups. Also, the most common pneumatization pattern in the perilabyrinthine region, was pattern B (pneumatization in the medial or lateral parts of the canal) in all LM groups. This finding is consistent with the results reported by Tan and colleagues. In their study, which was performed on individuals without any evidence of ear pathology, the labyrinth was used as the reference structure for categorization of pneumatization in the petrous apex. The results showed that group 2 (pneumatization of less than half of the petrous apex medial to the labyrinth), which resembles pattern B in our study, had the highest frequency (58.8%) [16]. The reason for the higher frequency of less pneumatized patterns in the temporal bones in our study is that we evaluated the CT scans of individuals with complaints of sinus problems, while no healthy population was examined.

In the present study, at higher severities of CRS (scores > 6), differences in the frequency percentage of pneumatization patterns A and C and also patterns B and C in the petrous apex were more significant than that reported at lower severities of CRS. The highest frequency of pattern A (no pneumatization) in the petrous apex was found at higher CRS severities (scores > 6), while the highest frequency of pattern C (complete pneumatization) in the petrous apex was reported at lower severities of CRS (0–6). In other words, with an increase in the severity of CRS, pneumatization reduced, which was statistically significant (P = 0.017). These results can be explained by the fact that mucosal edema and sinonasal secretions associated with CRS lead to the closure of the Eustachian tube and dysregulating the middle ear pressure [17].

Aoki et al. [18] showed that any Eustachian tube dysfunction can result in sclerosis in early years of life by preventing the resorption of spongy bone lacunae in the internal metabolic layer of the mastoid part of the temporal bone. Nevertheless, Lee et al. [8] believed that this mechanism also occurs during adulthood, which is in accordance with the results of the present study on adults.

Moreover, in the study by Lemmerling et al. [19], who evaluated the radiographic images of patients with temporal bone infections, it was shown that chronic infection in the middle ear leads to the thickening and reduction of TBP. Since paranasal sinuses and middle ear of the temporal bone have similar epithelia, and the drainage pathway of paranasal sinuses in the nasopharynx is adjacent to the Eustachian tube (ventilation/drainage pathway for the temporal bone), paranasal sinus pathogens can lead to temporal bone dysfunction [20, 21], therefore, through this mechanism, CRS may reduce TBP.

In a study by Gupta et al. [22], investigating the relationship between rhinosinusitis and tympanosclerosis (a condition resulting in calcification and deposition of calcium and phosphorus in the tissues of middle ear and mastoid cavity), a strong correlation was found between the recurrence of sinusitis, blockage of Eustachian tube, and formation of tympanosclerosis, which is similar to the results of the present study. Although in the present study, the highest frequency of pneumatization pattern A (no pneumatization) in the perlabyrinthine region was observed at higher severities of CRS (scores > 6), and the highest frequency of pattern C (complete pneumatization) was found at lower CRS severities (0–6), the perilabyrinthine pneumatization pattern was not significantly associated with CRS severity (P = 0.589).

According to the present study, the petrous segment of the internal carotid canal is a better reference structure for predicting the relationship between TBP and CRS, as confirmed in a study by Nemade et al. [15]. This study showed that the petrous apex of the carotid canal is a simple and reliable anatomical landmark for the study of TBP.

As one of the functions of the temporal bone air system is to adjust the middle ear pressure, it can be said that patients with less pneumatization are more prone to otitis media due to negative pressure on the middle ear [23, 24]. Therefore, based on the present findings, CRS can increase the middle ear’s susceptibility to infection by impairing the function of Eustachian tube and reducing TBP.

Furthermore, in the present study, pneumatization patterns in the petrous apex and perilabyrinthine regions were not significantly associated with the severity of CRS in both age groups. However, the frequency of TBP pattern A (no pneumatization) in the perilabyrinthine region increased as the severity of CRS advanced in both age groups; also, in the petrous apex, this association was reported in the age group of 18–40 years.

In the present study, the petrous apex and perilabyrinthine pneumatization patterns were not significantly associated with the severity of CRS in both sexes. Nevertheless, the frequency of pneumatization pattern A in the perilabyrinthine region increased in both sexes as the CRS severity increased; regarding the petrous apex, this association was observed in the female sex.

Conclusion

The present study showed that with an increase in the severity of CRS, pneumatization in the petrous apex with the carotid canal as the reference structure reduces based on LM radiological observations; this can be due to the temporal bone sclerosis in response to the Eustachian tube dysfunction and common pathogens with CRS. Also, this association was found by using the perilabyrinthine region as the reference structure, although it was not statistically significant. Therefore, the carotid canal is a better reference structure for evaluating the relationship between TBP and CRS. Based on the findings, there was no significant relationship between TBP and severity of CRS in the two sex and age groups.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Elahe Rafiee (Department of Biostatistics, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran) for her assistance in analyzing the statistical data. This study supported financially by Vice Chancellery for Research and Technology and Research center of allergic diseases of nose and sinuses of Guilan University of medical sciences, IR.GUMS.REC.1397.248.

Authors' Contribution Statements

FK: Review of article, Data analysis, Writing and Critical review. ZD: Concept, Design, Data Analysis, Writing and Critical review the paper. MMJ: Concept, Data analysis, Critical review the paper. NK: Data gathering, Writing the paper, Critical review the paper.

Funding

This study was funded by Vice Chancellery for Research and Technology of Guilan University of medical sciences.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. It approved by Vice Chancellery for Research and Technology and Research center of allergic diseases of nose and sinuses of Guilan University of medical sciences, IR.GUMS.REC.1397.248.

Publish Consent

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of the images in Figure(s) 1 and 2.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Farnoosh Khaksari, Email: f.khaksari@gmail.com.

Zahra Dalili Kajan, Email: zahradalili@yahoo.com.

Mir Mohammad Jalali, Email: mmjalali@gmail.com.

Negar Khosravifard, Email: ngkhosravi@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Sozen E, Celebi I, Ucal YO, Coskun BU. Is there a relationship between subjective pulsatile tinnitus and petrous bone pneumatization? J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24(2):461–463. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31826cffe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seifert CM, Harvey RJ, Mathews JW, Meyer TA, Ahn C, Woodworth BA, et al. Temporal bone pneumatization and its relationship to paranasal sinus development in cystic fibrosis. Rhinology. 2010;48(2):233–238. doi: 10.4193/Rhin09.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Esawi SR HA, Takhtani D, Hussain S (2017) Temporal bone hyperpneumatization and tinnitus: clinico-radiological evaluation using CT scan. J Global Radiol. 10.7191/jgr.2017.1034.

- 4.Jadhav AB, Fellows D, Hand AR, Tadinada A, Lurie AG. Classification and volumetric analysis of temporal bone pneumatization using cone beam computed tomography. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;117(3):376–384. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.12.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hindi K, Alazzawi S, Raman R, Prepageran N, Rahmat K (2014) Pneumatization of mastoid air cells, temporal bone, ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses. Any correlation? Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 66(4):429–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Park H, Hong SN, Kim HS, Han JJ, Chung J, Seo MW, et al. Determinants of conductive hearing loss in tympanic membrane perforation. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;8(2):92–96. doi: 10.3342/ceo.2015.8.2.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cinamon U. The growth rate and size of the mastoid air cell system and mastoid bone: a review and reference. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;266(6):781–786. doi: 10.1007/s00405-009-0941-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee DH, Jung MK, Yoo YH, Seo JH. Analysis of unilateral sclerotic temporal bone: how does the sclerosis change the mastoid pneumatization morphologically in the temporal bone? Surg Radiol Anat. 2008;30(3):221–227. doi: 10.1007/s00276-008-0310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gencer ZK, Ozkiris M, Okur A, Karacavus S, Saydam L. The possible associations of septal deviation on mastoid pneumatization and chronic otitis. Otol Neurotol. 2013;34(6):1052–1057. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182908d7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khalmuratova R, Park JW, Shin HW. Immune cell responses and mucosal barrier disruptions in chronic rhinosinusitis. Immune Netw. 2017;17(1):60–67. doi: 10.4110/in.2017.17.1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam K, Schleimer R, Kern RC. The etiology and pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis: a review of current hypotheses. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15(7):41. doi: 10.1007/s11882-015-0540-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuo CL, Yen YC, Chang WP, Shiao AS. Association between middle ear cholesteatoma and chronic rhinosinusitis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143(8):757–763. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopkins C, Browne JP, Slack R, Lund V, Brown P. The Lund-Mackay staging system for chronic rhinosinusitis: how is it used and what does it predict? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(4):555–561. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashraf N, Bhattacharyya N. Determination of the "incidental" Lund score for the staging of chronic rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125(5):483–486. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.119324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nemade SV, Shinde KJ, Rangankar VP, Bhole P. Evaluation and significance of Eustachian tube angles and pretympanic diameter in HRCT temporal bone of patients with chronic otitis media. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;4(4):240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.wjorl.2017.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dexian Tan A, Ng JH, Lim SA, Low DY, Yuen HW. Classification of temporal bone pneumatization on high-resolution Computed Tomography: prevalence patterns and implications. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;159(4):743–749. doi: 10.1177/0194599818778268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tangbumrungtham N, Patel VS, Thamboo A, Patel ZM, Nayak JV, Ma Y, et al. The prevalence of Eustachian tube dysfunction symptoms in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018;8(5):620–623. doi: 10.1002/alr.22056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aoki K, Esaki S, Honda Y, Tos M (1990) Effect of middle ear infection on pneumatization and growth of the mastoid process. An experimental study in pigs. Acta Otolaryngol 110(5–6):399–409 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Lemmerling MM, De Foer B, Verbist BM, VandeVyver V. Imaging of inflammatory and infectious diseases in the temporal bone. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2009;19(3):321–337. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wald ER (2011) Acute otitis media and aacute bacterial sinusitis. Clin Infect Dis 52(suppl_4):S277–S83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Damar M, Dinc AE, Erdem D, Biskin S, Elicora SS, Kumbul YC. The role of the nasal and paranasal sinus pathologies on the development of chronic otitis media and its subtypes: A computed tomography study. Niger J Clin Pract. 2017;20(9):1156–1160. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_124_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta R, Tiwari D. Tympanosclerosis and recurrent sinusitis: an association found in our retrospective study. J Dental Med Sci. 2016;15(12):43–45. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koc A. The role of Mastoid pneumatization in the pathogenesis of Tympanosclerosis. Int Adv Otol. 2012;8(3):426–433. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quesnel AM, Ishai R, McKenna MJ. Otosclerosis: temporal bone pathology. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018;51(2):291–303. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]