Abstract

Pneumosinus dilatans is an abnormal expansion of the air-filled paranasal sinuses. Usually found incidentally on radiology, it does rarely present in the form of cosmetic, neurological, ocular or rhinological pathologies. We report a case of a young male with complaints of bilateral gradual vision loss, diagnosed as pneumosinus dilatans with optic nerve atrophy. He underwent bilateral optic nerve decompression. A review of all cases of pneumosinus dilatans, reported over the last 100 years in English literature is presented.

Keywords: Pneumosinus dilatans, Hypersinus, Pneumatocele, Optic nerve atrophy

Introduction

Pneumosinus dilatans (PSD) is a rare, benign pathology of the paranasal sinuses. It refers to the abnormal dilatation of a paranasal sinus, due to hyperpneumatisation [1]. Meyes in the year 1898 described enlargement of the paranasal sinuses for the first time and named it pneumatocoele [2]. The term- ‘pneumosinus dilatans’ was first given in 1918 by Benjamin [2]. Incidence is most frequent in the frontal sinus (63%), followed by sphenoidal sinus (25%), maxillary sinus (19%), and ethmoidal sinus (18%), usually affecting only a single sinus cavity, however, multiple or all sinuses maybe involved [3]. This condition has a variable range of presentation, from asymptomatic patients to those with nasal obstruction, facial deformities, pain or visual changes.

Materials and Methods

A case of pneumosinus dilatans with bilateral optic nerve atrophy is reported. A systematic search of the English literature was conducted with the keywords- pneumosinus dilatans, dilated pneumosinus, hyperpneumatization and pneumatocele, through the PubMed database. All reported cases and review articles on the subject were studied. Individual reports already included in the review articles were excluded to remove duplication. Reports with inadequate information or uncertain diagnosis were excluded.

Case Report

A 15-year-old male, presented to the hospital with complaints of decreased vision in both eyes, which was gradual in onset and progressing over the last 2 months. There was no history of trauma, facial pain, nasal bleeding, nasal obstruction, headache, or any ocular complaints. Visual acuity was restricted to perception of light bilaterally. Pupils were mildly reactive. Fundus examination revealed a pale disc with peripapillary atrophy and tessellated fundus. There were no significant findings on anterior rhinoscopy. Computerized tomography (CT) of nose and paranasal sinuses revealed diffuse and marked enlargement of all paranasal sinuses (hyper-pneumatization), suggestive of PSD (Fig. 1). Narrowing of bilateral optic canals was identified. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also showed enlarged hyper-pneumatized sinuses with thinning of cortical margins and calvarial plate in the region of frontal sinuses (Fig. 2). Routine investigations and pre-anaesthetic evaluation were insignificant. After a detailed written consent, the patient was taken up for bilateral optic nerve decompression under general anaesthesia. Bilateral middle meatal antrostomy, ethmoidectomy and sphenoidotomy was performed. Lamina papyracea was delineated. Optic tubercle was identified.180 degrees of bone over the optic canals was removed, decompressing the optic nerves bilaterally. There were no post-operative complications. At 2 year follow up, there was no subjective improvement in the patient’s symptoms.

Fig. 1.

Coronal CT images showing extreme pneumatization of the paranasal sinuses with bony remodelling

Fig. 2.

MRI Coronal and Sagittal images revealing pan-sinus expansion

Discussion

PSD is a rare condition usually found in young men in their 20 s to 40 s, but can affect both sexes at any age [4]. It is characterised by progressive expansion of one or more paranasal sinuses beyond the normal margins without any changes in the mucous membrane. The expansion may involve either a part of the sinus or the whole sinus [5]. Urken et al. [6] proposed a classification system, dividing these enlarged and aerated sinuses into 3 categories, namely:

Hypersinus: extends beyond the upper limit of normal boundaries of the sinus but within the normal range of the affected bone and with normal sinus walls; usually asymptomatic

Pneumatocoele: extends beyond normal anatomic boundaries of the sinus. Displaced sinus walls and focal/generalized thinning of the bony sinus wall. Local pressure symptoms maybe present

PSD: extends beyond the normal anatomic boundaries of the sinus and affected bone. Displaced sinus walls and normal bony thickness. May present clinically with some local pressure symptoms.

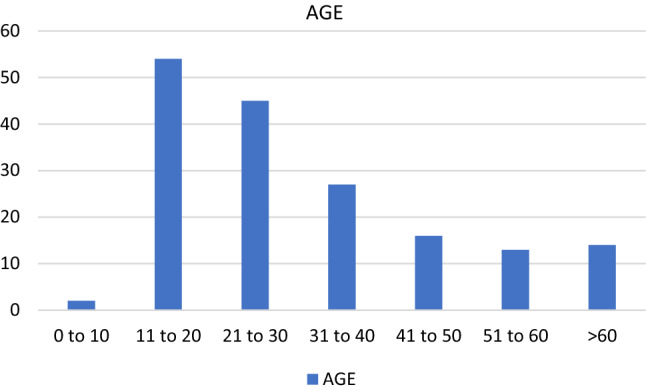

A total of 90 articles were identified in relation to PSD. 15 of those were review articles. Only the case reports not already a part of a review article were included in the analysis. A total of 171 cases of PSD have been documented in literature, including this case, from the year 1918–2020. Of 171 patients, 119 (69.5%) were males. 31.5% of the patients belonged to the 11–20 years age bracket (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Incidence of PSD by age of the patients in 10 year intervals (n = 171)

Individual sinus involvement (80.1%) was more common than multi-sinus involvement, of which, frontal sinus and ethmoid sinus were the most and least commonly involved, respectively. The most common presentation was swelling over the forehead. 19.3% of the patients presented only with cosmetic concerns. Table 1 shows the different symptoms of presentation. 85 (49.7%) cases had an associated pathology with PSD, of which meningioma and arachnoid cyst were the most common. Other associated conditions are enlisted in Table 2. The other half with no associated pathology were considered as isolated PSD.

Table 1.

Presenting symptoms and their prevalence

| Presenting symptom/s | Number of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Swelling on forehead | 37 |

| 2 | Decrease in vision | 34 |

| 3 | Headache | 28 |

| 4 | Swelling over cheek | 22 |

| 5 | Incidental finding | 20 |

| 6 | Proptosis | 18 |

| 7 | Pain/ pressure | 15 |

| 8 | Neurological / psychiatric symptoms | 14 |

| 9 | Diplopia | 6 |

| 10 | Others | 21 |

Table 2.

Conditions associated with PSD

| Associated conditions | No. of patients |

|---|---|

| Meningioma | 32 |

| Arachnoid cyst | 14 |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis | 11 |

| Fibrous dysplasia/osteitis fibrosa localista/osteoma/ossifying fibroma | 6 |

| Hydrocephalus ± meningitis | 5 |

| Others | 17 |

| None | 86 |

74 reported patients with PSD were found to have complaints regarding vision (diplopia, decrease in vision or complete loss of vision). While there is no available data on treatment for 44 of these patients, 30 patients underwent surgery for their condition. Of those patients who underwent surgery, 20 patients showed subjective as well as objective improvement in their symptoms, 2 documented a further deterioration in vision and 8 had no improvement post operatively.

Although a considerable number of cases have been recorded, the true incidence as well as the aetiology of the condition have not been clearly established. Since a significant proportion of patients only present with cosmetic concerns or are diagnosed on radiology alone, it is safe to assume that the true incidence may be much higher than anticipated. PSD can be classified into primary (idiopathic) and secondary types. Various hypothesis has been postulated for primary PSD, including hormonal imbalance, infection with gas forming organisms, spontaneously discharging mucocele [7]. A popular theory is of one-way (ball) valve effect, which is supported by presence of polypoid mucus in drainage pathway of the sinus involved [8]. Osteogenic diseases were suggested as the aetiology by Jankowsky et al. [9].

Desai et al. concluded that sphenoid PSD had a 24% and frontal PSD had a 22% chance of having a meningioma or arachnoid cyst associated with it. Those with ethmoidal involvement had a 17% arachnoid cyst incidence [10]. The association of PSD with meningiomas and arachnoid cysts, both intracranial pathologies, have directed a theory that a disruption in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) dynamics may result in dilatation of the paranasal sinuses via alterations in the intracranial pressure [4, 11]. Arachnoid cysts and meningiomas may disrupt CSF dynamics via compression of cerebral blood flow. The compression of the cerebral arteries can impair CSF flow within the ventricular system while the compression of the cerebral veins can result in inhibited CSF absorption.

The secondary type of PSD is usually syndromic, due to over development of sinuses to compensate for association with agenesis of brain, as in cranio-cerebral hemiatrophy [12] or due to decreased intracranial pressure [11].

Usually, the patients are asymptomatic, however, if present, the clinical features depend on the sinus involved [12]. Clinical presentations of PSD entail different types of facial deformities in the form of proptosis or exophthalmos, cheek mass, alveolar swelling, and prominence of nasolabial fold, nasal obstruction, and impairment in visual acuity [13]. Frontal bossing is the most common presentation in case of involvement of frontal sinus [14]. Sphenoidal and ethmoidal PSD have been linked to ocular symptoms varying from blurred vision to temporal field defects, or acute loss of vision [15]. 52% of PSD patients with sphenoid sinus involvement also report vision loss and 22% of ethmoidal PSD have exophthalmos [10]. Involvement of maxillary sinus is also associated with cosmetic deformities. Maxillary PSD must be differentiated from other pathologies of maxillary sinus like neoplastic lesions, mucoceles, and acute complicated rhinosinusitis [13]. The association of PSD with fibro-osseous lesions and other disorders of osteogenesis may be explained by the abnormal bone formation. Since it is associated it syndromic diseases as well, it may be prudent to investigate a genetic association in these patients.

CT scans and MRI play an important role in the diagnosis of this condition by giving information about the bony deformities and erosions as well as to rule out any associated intracranial abnormality, respectively [10]. The width and height of the involved sinus can be measured in millimetre on a coronal section of a CT scan, whereas the volume can be measured in cubic metre [16]. PSD needs radiological assessment for diagnosis, establishing extent, causality and discovering associated conditions.

Facial swelling due to frontal sinus involvement is the most common presentation. Treatment in these will depend on the size of swelling and may be purely cosmetic. The treating surgeon must rule out involvement of other sinuses and associated conditions and the patients must be counselled accordingly. Regarding the best course of action in patients that present with changes in visual acuity, no consensus can be achieved at present. Visual impairment can be severe and may need early surgical intervention. Although there is little evidence in favour of surgery, optic atrophy on radiology would suggest decompression to be the best course of action. Our patient did not have any improvement in vision after surgery, but decompression may have halted further deterioration of vision which has remained the same for the last 24 months. In cases where radiological evidence of optic nerve canal involvement is evident, we recommend an early surgical decompression for preservation of vision.

Conclusion

The true incidence and etiology of PSD remain uncertain, but meningiomas, arachnoid cysts and vision loss have been irrefutably linked to it. Where sphenoid sinus is involved the incidence of vision loss has been reported in more than half the patients and meningiomas are found in a fifth of all patients. Therefore, all patients with PSD must be further investigated, and at-risk patients identified and counselled according to the degree and location of involvement. A high index of suspicion is also necessary to identify PSD as the cause of deteriorating vision and once identified a prompt surgical intervention should be undertaken.

Funding

None.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alatar AA, AlSuliman YA, Alrajhi MS, Alfawwaz FS. Maxillary pneumosinus dilatans presenting with proptosis: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Med Insights Ear Nose Throat. 2019;12:1179550618825149. doi: 10.1177/1179550618825149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thimmasettaiah NB, Chandrappa RG, Sukumari S (2014) Pneumosinus dilatans frontalis: a case report. Transl Biomed 5(1)

- 3.Ricci JA. Pneumosinus dilatans: over 100 years without an etiology. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75:1519–1526. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sweatman J, Beltechi R. Pneumosinus dilatans: an exploration into the association between arachnoid cyst, meningioma and the pathogenesis of pneumosinus dilatans. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2019;185:105462. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2019.105462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walkeec JL, Jones NS. Pneumosinus dilatans of the frontal sinuses: two cases and a discussion of its aetiology. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116:382–385. doi: 10.1258/0022215021910852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Urken ML, Som PM, Lawson W, Edelstein D, Weber AL, Biller HF. Abnormally large frontal sinus. II. Nomenclature, pathology, and symptoms. Laryngoscope. 1987;97:606–611. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198705000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vlckova I. White PS rapidly expanding maxillary pneumosinus dilatans. Rhinology. 2007;45(1):93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teh BM, Hall C, Chan SW. Pneumosinus dilatans, pneumocoele or air cyst? A case report and literature review. J Laryngol Otol. 2012;126(01):88–93. doi: 10.1017/S0022215111002283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jankowski R, Kuntzler S, Boulanger N, Morel O, Tisserant J, Benterkia N, Vignaud JM. Is pneumosinus dilatans an osteogenic disease that mimics the formation of a paranasal sinus? Surg Radiol Anat. 2014;36(5):429–437. doi: 10.1007/s00276-013-1222-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desai NS, Saboo SS, Khandelwal A, Ricci JA. Pneumosinus dilatans: is it more than an aesthetic concern? J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25(2):418–421. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000000694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Schayck R, Niedeggen A. Pneumosinus dilatans after prolonged cerebrospinal fluid shunting in young adults with cerebral hemiatrophy. A report of two cases and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev. 1992;15:217–223. doi: 10.1007/BF00345938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dyke CG, Davidoff LM, Masson CB. Cerebral hemiatrophy with homolateral hypertrophy of the skull and sinuses. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1933;57:588–600. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi EC, Shin HS, Nam SM, Park ES, Kim YB. Surgical correction of pneumosinus dilatans of maxillary sinus. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22(3):978–981. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31820fe30e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Appelt EA, Wilhelmi BJ, Warder DE, Blackwell SJ. A rare case of pneumosinus dilatans of the frontal sinus and review of the literature. Ann Plast Surg. 1999;43(6):653–656. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199912000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aryan A, Thakar S, Jagannatha AT, Channegowda C, Rao AS, Hegde AS. Pneumosinus dilatans of the spheno-etmoidal complex associated with hypovitamonosis D causing bilateral optic canal stenosis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2017;33(6):1005–1008. doi: 10.1007/s00381-017-3373-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tatlisumak E, Asirdizer M, Bora A, Hekimoglu Y, Etli Y, Gumus O, Keskin S. The effects of gender and age on forensic personal identification from frontal sinus in a Turkish population. Saudi Med J. 2017;38(1):41. doi: 10.15537/smj.2017.1.16218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]