Abstract

Describe experience of managing paranasal sinus mucoceles, with either endoscopic endonasal approach (EESS) or combined external with EESS approach. Retrospective study done at SDMCMS&H, between 2007 and 2019, on patients undergoing surgical excision of mucocele. Results described as mean, median, mode, percentages. Twenty-one patients were included, with male to female ratio (0.75:1), mean age (42.95 years). Commonest presentation were facial pain (42.85%),visual symptoms (28.57%), headache (23.80%). Signs included, proptosis (52.38%), facial deformity (23.80%). Imaging: showed frontal mucoceles (42.85%), fronto-ethmoid (38.09%), ethmoid (14.28%), sphenoid (4.76%). Orbital extension in 42.85%, sinusitis (33.33%), skull base erosion (23.80%). EESS or combined external and EESS approach (61.90%, 38.09% respectively) were performed. Complete excision of mucocele wall done. Recurrence in two cases(average-2.5 years),revision surgery performed without further recurrences. Either EESS or combined external and EESS approach used based on site and extension of mucoceles. Complete peeling of mucocele wall without obliteration of the sinus cavity was the mode of surgical management in all cases.

Keywords: Mucoceles, Paranasal, Sinus, Frontal

Introduction

Mucoceles are benign pseudo cystic, slow-growing, expansile lesions in the paranasal sinuses that develop at the expense of sinus cavities and contain aseptic mucus, often lined by an epithelium, which is either pseudostratified columnar and less often squamous cell lining with inflammatory cell infiltrate [1–3]. It is the most common benign expansile lesion of the paranasal sinuses [4].

It is often seen in adults and is rare in pediatric population, and necessitates a workup for systemic disease like cystic fibrosis, if present [5]. The most common locations are the frontal and ethmoid sinus. Maxillary and sphenoid sinus are less often affected [6]. The diagnosis is based on the history, physical examination and radiological findings. Computed Tomography (CT) is the preferred imaging modality for mucoceles [7]. Clinical symptoms of sinusitis specifically, headache or facial pain is often seen. If intracranial or orbital extension has occurred, patients may report visual disturbances or exhibit proptosis [8].

The present study describes the clinical profile, intraoperative experience and outcomes of a series of patients who underwent surgical treatment for paranasal sinus mucoceles at the otorhinolaryngology service of our hospital. This article emphasizes the importance of complete excision of mucocele as against simple marsupialization.

Materials and Methods

This was a hospital based retrospective study conducted at SDM College of Medical Sciences and Hospital, Dharwad in the department of otorhinolaryngology. Data was collected from records of patients who underwent surgical treatment for paranasal sinus mucoceles at the facility between December 2007 to December 2019. Information was collected regarding age, sex and their mode of presentation like pain, facial deformity, visual abnormalities (Table 1).

Table 1.

.

| Mode of presentation | Number of cases | Percentage of cases (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Facial pain | 09 | 42.85 |

| Visual symptoms | 06 | 28.57 |

| Headache | 05 | 23.80 |

| Nasal obstruction | 03 | 14.28 |

All patients had undergone computed tomography (CT) which was done to determine the anatomy of paranasal sinuses, location of mucoceles, presence of orbital or intracranial extension, and for surgical planning of the cases. In patients with orbital extension and skull base erosions, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) had been performed (Fig. 1).

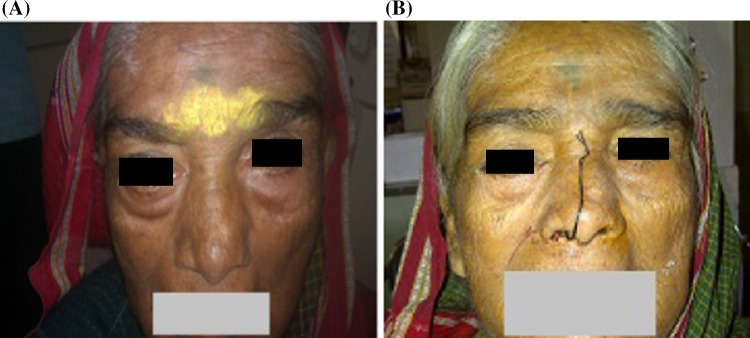

Fig. 1.

a Preoperative and b post-operative picture of patient who presented with right proptosis

Treatment consisted of either endonasal endoscopic sinus surgery (EESS) or combined external and EESS approach. Intraoperative findings and complications were compiled. Patients are followed up for up to 10 years, with the most recent cases being in follow-up till date. Recurrences were noted.

Mean, mode, range, percentages were used to tabulate results.

Results

A total of 21 patients were included in the study. Number of male patients were 9 and females were 12 with male to female ratio of 0.75:1. The mean age of presentation was 42.95 years, median being 50 years and with the youngest case aged 9 years and the oldest was 69 years (Fig. 2).

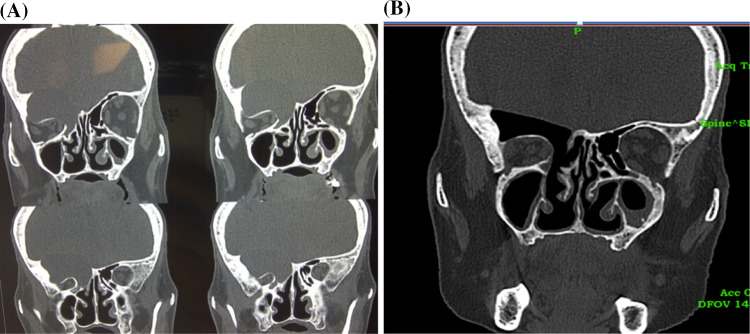

Fig. 2.

a Preoperative CT scan of serial coronal cuts showing right fronto-ethmoidal mucocele with partial erosion of roof of orbit and fovea and compression of orbital structures, b post-operativeCT scan of same patient, with intact dura

The chief complaints in order of frequency are as per Table 1.

Visual symptoms included diplopia in 3 patients, excessive watering in 2 and blurring of vision in 1 patient.

On examination, following signs were documented as per Table 2.

Table 2.

.

| Signs | Number of cases | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Proptosis | 11 | 52.38 |

| Facial deformity | 05 | 23.80 |

| Nasal discharge | 03 | 14.28 |

| Deviated Nasal septum (DNS) | 03 | 14.28 |

| Chemosis of the eye | 01 | 4.76 |

| Restricted eye movements | 01 | 4.76 |

| Discharging fistula | 01 | 4.76 |

CT findings showed the following paranasal sinus involvement in order of frequency with additional findings (Table 3). MRI was done in 10 cases.

Table 3.

.

| Number | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Frontal (exclusively) | 09 | 42.85 |

| Fronto-ethmoid | 08 | 38.09 |

| Ethmoid | 03 | 14.28 |

| Sphenoid | 01 | 4.76 |

| Maxillary | 00 | 00 |

| Additional findings | ||

| Orbital extension | 09 | 42.85 |

| Sinusitis | 07 | 33.33 |

| Skull base erosion | 03 | 14.28 |

Orbital extension included, breach of lamina papyracea in 4 cases, superior orbital erosion in 5 cases with frontal sinus mucoceles. Skull base erosions included erosion of roof of ethmoid/fovea in 2 cases, posterior extension eroding into frontal lobe in 1 case.

In three cases, thickened bony walls and septations of affected sinuses especially in ethmoid mucoceles were noted.

All patients underwent surgery under general anesthesia with EESS performed in 13 cases (61.90%) and combined approach in 08 patients (38.09%). A team comprising of ENT surgeons (primary surgeon and assistant) along with ophthalmologist wherever necessary were involved (Fig. 3).

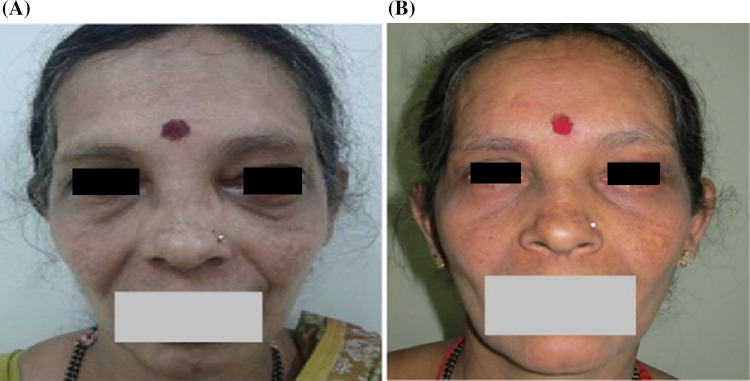

Fig. 3.

Pre-operative (a) and post-operative (b) picture of patient who presented with left proptosis

Endonasal Endoscopic Sinus Surgery

Under aseptic precautions and general anaesthesia, parts were painted and draped. Nasal mucosa decongested and septal correction was done, if necessary. 4 mm zero degree endoscope introduced into nasal cavity. In cases of frontal mucoceles, uncinectomy, middle meatal antrostomy done. Identification of agar nasi followed by anterior ethmoidectomy done. Frontal sinusotomy done and mucocele wall punctured, excision of bony wall of mucocele done after draining its contents. For fronto-ethmoid and ethmoid mucolceles, anterior wall was seen in middle meatus itself. In some cases, uncinate process and maxillary ostium was obscured by the mucocele. And in few cases, bony wall of mucocele was very hard, which had to be drilled/punched with Kerrison’s punch (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

a Preoperative CT-PNS of same patient showing left frontal mucocele with erosion of the superior wall of orbit and compression of orbital structures, b post-operative CT of same patient

Endoscope Assisted External Approach

This procedure had been performed along with endonasal endoscopic approach for the mucoceles extending lateral to orbital midline as accessibility for these lesions was difficult by endonasal endoscopic approach alone (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Preoperative ct scan of patient with left frontal mucocele who presented with left infraciliary discharging fistula

2% Lignocaine with 1:200,000 adrenaline infiltration was given in brow region. Incision was placed over lateral region of brow avoiding the supra-orbital and supra-trochlear nerve and blood vessels. Periosteum was incised and retracted. Opthalmologist’s assistance was taken to retract the eye ball using retractor. 10 mm opening made to enter into the sinus. Size of opening was enough for introduction of endoscope with one instrument at one time. Zero-degree 4 mm endoscope was used to enter through the opening and visualize the sinus cavity with pathology. Zero degree 2.7 mm and 30°. 4 mm scopes were used when appropriate. Mucocele wall was peeled off completely with instruments like freers elevator, suction cannula, double end knife(otology instrument). NO SINUS CAVITY OBLITERATION WAS DONE. Brow incision was sutured in two layers.

For one patient with a discharging fistula, incision was placed, which included the discharging fistula Fig. 6a. Tract was noticed to be attached to the mucocele wall on dissection. The fistulous tract with mucocele wall was removed completely and wound sutured in layers.

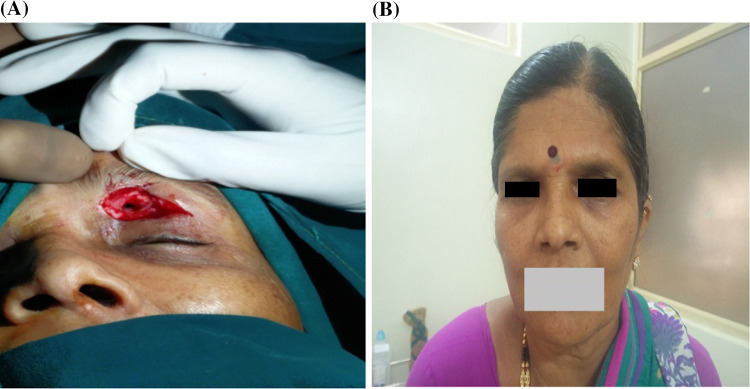

Fig. 6.

a intra operative picture of the same patient showing external approach with incision around the fistulous opening, b post-operative picture of the same patient with healed operative site

Intra operative complications were seen in 2 cases in the form of periorbital fat exposure.

On follow-up, two patients had recurrence, one was with frontal sinus mucocele and the other with fronto-ethmoid mucocele, for which revision surgery was performed. No orbital infections were noted. Recurrences were seen at 2 and 3 years respectively.

Discussion

Mucoceles are known to occur post obstruction of sinus ostia and have fluid accumulation within them, that gradually enlarge resulting in erosion and remodeling of surrounding tissues. Even though benign, they can still cause significant pathology in paranasal sinuses [9]. Cystic development of embryonic residues, cystic dilatation of the glandular structures, and even atypical form of craniopharyngioma are other theories proposed [10, 11]. The present study was a single centre experience of managing 21 patients with paranasal sinus mucoceles.

The usual age of presentation is known to be between the fifth and sixth decades of life [1, 12]. In the present study, mean age of presentation was 42.95 years, median was 50 years, with minimum and maximum ages were 9 years and 68 years respectively, which was in concordance to literature, and study done by Jaswal et al. [4] where mean age was 43.68 years.

There was a small female preponderance noted in the study with male to female ratio of 0.75:1, even though some studies have not demonstrated any gender bias [13, 14]. Series of patients published by Caylakli et al. [9] from Ankara Turkey, demonstrated male preponderance and females were more often affected, similar to our findings in study done by Jaswal et al. [4] reflecting possible female bias in Indian population.

The most common mode of presentation was facial pain (09 cases, 42.85%), visual symptoms in 6 cases (28.57%), headache in 5 (23.80%) and nasal obstruction in 3 (14.28%). Caballero García et al. [15] found fronto orbital headache in 87% cases, oculomotor palsies in 55, nasal symptoms in 38% that included anosmia, nasal discharge and nasal obstruction.

On examination, proptosis was seen in 52.38% patients, followed by facial deformity in 23.80%, nasal discharge, DNS in 14.28% and in 4.76% cases, chemosis of eyes, restricted eye movements and discharging fistula were seen in the current study. Similar to these results, Plantier et al. [5] found, proptosis, to be predominant finding, in 30.4%, and visual disturbance in 13%. Facial swelling, however was the most common observation (81.25%) in study by Jaswal et al. [4].

CT reports were available for all cases, MRI in cases with orbital or skull base extension. The most common type of mucoceles were frontal (42.85%) followed by fronto-ethmoid (38.09), ethmoid (14.28%), sphenoid in one case (4.76%) and none of maxillary sinus. Orbital extension was seen in 42.85%, sinusitis in 33.33% and skull base erosion in 23.80%. Plantier et al. [5] found, frontal mucoceles to be the commonest type, as per the current study. However, in their cohort, most cases had extension into either ethmoid or maxillary sinus, which was not seen here. Rachida et al. [16] found mucoceles in, fronto-ethmoidal complex in 81%, maxillary sinusin 13% and in the sphenoidal sinus in 6%. The maxillary sinus mucoceles are rare and seen in less than 10% of cases, as per literature [9], which is in concordance with our findings.

The only effective treatment for paranasal sinus mucocele is surgery [17].

In this study, two techniques were followed according to requirement, as EESS or combined external and EESS approach (61.90%, 38.09% respectively). Courson et al., did a large meta-analysis with 542 patients (between 2002 and 2014). Of these, 53.9% were treated endoscopically, 37.5% via external access, and 8.8% via a combined approach [18]. Plantier et al. [5] found that only 18.5% required combined access, and others improved with EESS alone. Though traditionally, the treatment may be roughly divided into two categories: radical surgery and conservative surgery. Radical surgery that entailed complete extirpation of the mucus membrane with obliteration of the sinus cavity (with abdominal fat). Conservative surgery involved marsupialization with adequate drainage. Here, the approach comprised of complete excision of mucocele wall. In case of frontal sinus mucoceles, after complete excision of mucocele, the frontal sinus was not obliterated and recess was kept open. The results were comparable to the literature in terms of outcome.

Only two cases had intraoperative complications i.e. exposure of orbital fat. Diogo et found complications in three cases, with one having severe intra-op bleed.

On average, recurrence of paranasal sinus mucocele develops in the fourth year after surgery [1].

The average duration of presentation with recurrence in the current study was 2.5 years (in two cases, 9.52%). Literature dictates, the recurrence rate of mucoceles to be 9–23.5% [1, 19]. Revision surgery was needed in both, and repeat follow up showed no further recurrence in them. Follow up of all operated cases till date have not revealed any orbital complications, visual disturbances with acceptable improvement in proptosis correction.

Conclusion

Paranasal sinus mucoceles, are a group of benign, yet destructive lesions, which need prompt management. This was a single centre experience of managing 21 patients with the same. The mean age of presentation was 42.95 years, there was slight female preponderance. Most common mode of presentation was facial pain, with proptosis being most common examination finding. CT was diagnostic in all cases, with MRI being helpful in erosion/extension of disease. Frontal mucoceles were most common type, with 14 cases demonstrating orbital/skull base erosions.

Either EESS or combined external and EESS approach were used based on the site and extension of mucoceles. Complete peeling of mucocele wall without obliteration of the sinus cavity was the mode of surgical management in all cases. Intra operative complications and recurrence rates were comparable to literature.

Limitation

It was a retrospective study and proptosis was not measured objectively.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of Data and Materials

In house medical records.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Devars du Mayne M, Moya-Plana A, Malinvaud D, Laccourreye O, Bonfils P. Sinus mucocele: natural history and long-term recurrence rate. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2012;129(3):125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Facon F, Nicollas R, Paris J, Dessi P. La chirurgie des mucoceles sinusiennes: notre experience a propos de 52 cas suivi à moyen terme. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol. 2008;129(3):167–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milroy VJ, Lund CM. Fronto-ethmoidalmucocoeles:ahistopathological analysis. J Laryngol Otol. 1991;105(11):921–923. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100117827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaswal A, Jana AK, Sikder B, Jana U, Nandi TK. Paranasal sinus mucoceles: a comprehensive retrospective study in Indian perspective. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;60:117–122. doi: 10.1007/s12070-007-0116-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plantier DB, Neto DB, Pinna FR, Voegels RL. Mucocele: clinical characteristics and outcomes in 46 Operated Patients. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;23:88–91. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1668126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Har-El G. Endoscopic management of 108 sinus mucoceles. Laryngoscope. 2001;111(12):2131–2134. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200112000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saito Y, Hasegawa M, Hiratsuka H, Kern EB. Computed tomography in the diagnosis of mucoceles of sphenoid and ethmoid sinuses. Rhinology. 1980;18:51–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zainine R, Loukil I, Dhaouadi A, et al. Complications ophtalmiques des mucocèles rhino-sinusiennes. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2014;37(02):93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caylakli F, Yavuz H, Cagici AC, Ozluoglu LN. Endoscopic sinus surgery for maxillary sinus mucoceles. Head Face Med. 2006;2:29. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-2-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman A, Batra PS, Fakhri S, Citardi MJ, Lanza DC. Isolated sphenoid sinus disease: etiology and management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133(1):544–550. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hejazi N, Witzmann A, Hassler W. Ocular manifestationsofsphenoidmucoceles:clinicalfeaturesandneurosurgical management of three cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2001;56(1):338–343. doi: 10.1016/S0090-3019(01)00616-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrow EM, DelGaudio JM. In-office drainage of sinus Mucoceles: an alternative to operating-room drainage. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(05):1043–1047. doi: 10.1002/lary.25042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arrue P, Kany MT, Serrano E, et al. Mucoceles of the paranasal sinuses: uncommon location. J Laryngol Otol. 1998;112:840–844. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100141854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobson AL, Lawson W, Biller HF. Bilateral pansinus mucoceles with bilateral orbital and intracranial extension. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1982;90:507–509. doi: 10.1177/019459988209000428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CabarelloGarcia J, Giol Alvarez AM, Morales Perez I, Gonzales Gonzales N, Hidago Gonsales A, Cruz Perez PO. Endoscopic treatment of sphenoid sinus mucocele: case report and surgical considerations. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2017;2017:7567838. doi: 10.1155/2017/7567838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rachida B, Aouf LB, Korbi AE, Kolsi N, Harrathi K, Koubaa J. The role of imaging in the management of sinonasal mucoceles. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;34:3. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2019.34.3.18677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terranova P, Karligkiotis A, Digilio E, et al. Bonere generation after sinonasal mucocele marsupialization: What really happens over time? Laryngoscope. 2015;125(07):1568–1572. doi: 10.1002/lary.25157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Courson AM, Stankiewicz JA, Lal D. Contemporary management of frontal sinusmucoceles: ameta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(02):378–386. doi: 10.1002/lary.24309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scangas GA, Gudis DA, Kennedy DW. The natural history and clinical characteristics of paranasal sinus mucoceles: a clinical review. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3(09):712–717. doi: 10.1002/alr.21178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

In house medical records.