Abstract

Background

The symptoms and signs of schizophrenia have been linked to high levels of dopamine in specific areas of the brain (limbic system). Antipsychotic drugs block the transmission of dopamine in the brain and reduce the acute symptoms of the disorder. An original version of the current review, published in 2012, examined whether antipsychotic drugs are also effective for relapse prevention. This is the updated version of the aforesaid review.

Objectives

To review the effects of maintaining antipsychotic drugs for people with schizophrenia compared to withdrawing these agents.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Study‐Based Register of Trials including the registries of clinical trials (12 November 2008, 10 October 2017, 3 July 2018, 11 September 2019).

Selection criteria

We included all randomised trials comparing maintenance treatment with antipsychotic drugs and placebo for people with schizophrenia or schizophrenia‐like psychoses.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data independently. For dichotomous data we calculated risk ratios (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) on an intention‐to‐treat basis based on a random‐effects model. For continuous data, we calculated mean differences (MD) or standardised mean differences (SMD), again based on a random‐effects model.

Main results

The review currently includes 75 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving 9145 participants comparing antipsychotic medication with placebo. The trials were published from 1959 to 2017 and their size ranged between 14 and 420 participants. In many studies the methods of randomisation, allocation and blinding were poorly reported. However, restricting the analysis to studies at low risk of bias gave similar results. Although this and other potential sources of bias limited the overall quality, the efficacy of antipsychotic drugs for maintenance treatment in schizophrenia was clear. Antipsychotic drugs were more effective than placebo in preventing relapse at seven to 12 months (primary outcome; drug 24% versus placebo 61%, 30 RCTs, n = 4249, RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.45, number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) 3, 95% CI 2 to 3; high‐certainty evidence).

Hospitalisation was also reduced, however, the baseline risk was lower (drug 7% versus placebo 18%, 21 RCTs, n = 3558, RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.57, NNTB 8, 95% CI 6 to 14; high‐certainty evidence). More participants in the placebo group than in the antipsychotic drug group left the studies early due to any reason (at seven to 12 months: drug 36% versus placebo 62%, 24 RCTs, n = 3951, RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.65, NNTB 4, 95% CI 3 to 5; high‐certainty evidence) and due to inefficacy of treatment (at seven to 12 months: drug 18% versus placebo 46%, 24 RCTs, n = 3951, RR 0.37, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.44, NNTB 3, 95% CI 3 to 4).

Quality of life might be better in drug‐treated participants (7 RCTs, n = 1573 SMD ‐0.32, 95% CI to ‐0.57 to ‐0.07; low‐certainty evidence); probably the same for social functioning (15 RCTs, n = 3588, SMD ‐0.43, 95% CI ‐0.53 to ‐0.34; moderate‐certainty evidence).

Underpowered data revealed no evidence of a difference between groups for the outcome ‘Death due to suicide’ (drug 0.04% versus placebo 0.1%, 19 RCTs, n = 4634, RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.12 to 2.97,low‐certainty evidence) and for the number of participants in employment (at 9 to 15 months, drug 39% versus placebo 34%, 3 RCTs, n = 593, RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.41, low certainty evidence).

Antipsychotic drugs (as a group and irrespective of duration) were associated with more participants experiencing movement disorders (e.g. at least one movement disorder: drug 14% versus placebo 8%, 29 RCTs, n = 5276, RR 1.52, 95% CI 1.25 to 1.85, number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) 20, 95% CI 14 to 50), sedation (drug 8% versus placebo 5%, 18 RCTs, n = 4078, RR 1.52, 95% CI 1.24 to 1.86, NNTH 50, 95% CI not significant), and weight gain (drug 9% versus placebo 6%, 19 RCTs, n = 4767, RR 1.69, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.35, NNTH 25, 95% CI 20 to 50).

Authors' conclusions

For people with schizophrenia, the evidence suggests that maintenance on antipsychotic drugs prevents relapse to a much greater extent than placebo for approximately up to two years of follow‐up. This effect must be weighed against the adverse effects of antipsychotic drugs. Future studies should better clarify the long‐term morbidity and mortality associated with these drugs.

Plain language summary

Maintenance treatment with antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia

Antipsychotic drugs are the mainstay of treatment of schizophrenia, not only in the event of acute episodes, but also in the long‐term perspective. While people might want to stop their treatment at some stage, recurrences of psychotic symptoms are known to occur after treatment discontinuation. Relapses can lead to risk of harm, loss of autonomy and substantial distress for individuals and their families.

The current report presents the update version of a systematic review previously published in 2012, and is based on 75 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published over a long period since the 1950s and including more than 9000 participants. The effects of all antipsychotic drugs are here compared to those of placebo ‐ namely drug discontinuation ‐ for maintenance treatment, that is prevention of relapses. The aim is to explore the benefits and risks of each of the two options.

The results of this review show very consistently that antipsychotic drugs effectively reduce relapses and need for hospitalisation. Indeed, in case of treatment discontinuation, the risk of relapse at one year is almost three times higher. Antipsychotic drugs appear to have a positive effect on the ability to engage in activities and relationships, and on the possibility to fulfil remission from symptoms, although less evidence is available in this regard. Though based again on a lower number of reports, people continuing their treatment tend to experience higher satisfaction with their life, which confirms the negative consequences on well‐being of being at higher risk for recurrence. Conversely, antipsychotic drugs are, as a group, associated with a number of side effects such as movement disorders, weight gain and sedation. However, this review allows more understanding of the fact that stopping treatment is far more harmful than thoughtfully maintaining it.

Unfortunately, studies included in this review do generally last up to one year, and this makes difficult to clarify the longer‐term effect of these drugs. It is however true that the longer the study the more likely that other factors ‐ e.g. environmental – may accumulate and complicate the interpretation of results. Most of all, this review supports the advantages of antipsychotic drugs among many different types of participants. The best strategy would be therefore to continue treatment with antipsychotics, eventually discussing and adapting it if any adverse effect occurs.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Maintenance treatment with antipsychotic drugs versus placebo/no treatment for schizophrenia.

| Maintenance treatment with antipsychotic drugs versus placebo/no treatment for schizophrenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: schizophrenia Setting: inpatients and outpatients Intervention: maintenance treatment with antipsychotic drugs Comparison: placebo/no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Maintenance treatment with antipsychotic drugs versus placebo/no treatment | |||||

|

Relapse: 7 to 12 months Follow‐up: 7‐12 months |

606 per 1.000 | 230 per 1.000 (194 to 273) | RR 0.38 (0.32 to 0.45) | 4249 (30 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH1 2 3 4 | |

|

Leaving the study early: due to any reason (acceptability of treatment) Follow‐up: 1‐24 months |

541 per 1.000 | 292 per 1.000 (265 to 330) | RR 0.54 (0.49 to 0.61) | 7001 (56 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH5 6 | |

|

Service use: number of participants hospitalised Follow‐up: 1‐36 months |

177 per 1.000 | 76 per 1.000 (57 to 101) | RR 0.43 (0.32 to 0.57) | 3558 (21 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH6 7 | |

|

Death: due to suicide Follow‐up: 1‐15 months |

1 per 1.000 | 1 per 1.000 (0 to 4) | RR 0.60 (0.12 to 2.97) | 4634 (19 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW6 8 | |

|

Quality of life (various scales; low score=better) Follow‐up: 3‐18 months |

The mean quality of life in the intervention group was 0.32 standard deviations lower (from 0.57 to 0.07 standard deviations lower), with lower scores reflecting a better condition. | ‐ | 1573 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW5 6 9 10 11 | SMD ‐0.32 (‐0.57 to ‐0.07) | |

|

Number of participants in employment Follow‐up: 9‐15 months |

344 per 1.000 | 372 per 1.000 (282 to 486) | RR 1.08 (0.82 to 1.41) | 593 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW6 12 13 | |

|

Social functioning (various scales; low score=better) Follow‐up: 1‐15 months |

The mean social functioning in the intervention group was 0.43 standard deviations lower (from 0.53 to 0.34 standard deviations lower), with lower scores reflecting a better condition. | ‐ | 3588 (15 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE6 14 15 | SMD ‐0.43 (‐0.53 to ‐0.34) | |

| *The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

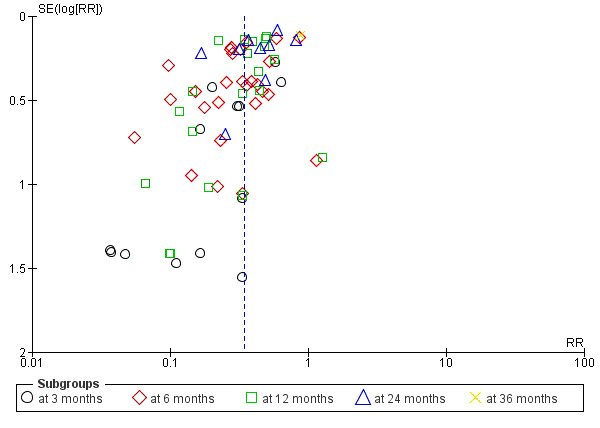

1 Publication bias: rated 'undetected' ‐ although the funnel plot was asymmetrical, the trim and fill test did not change the point estimate and the point estimate was also similar when only large studies were included (Analysis 3.5).

2 Risk of bias: rated 'no' ‐ many studies did not report the methods for sequence generation and/or allocation concealment. However, in subgroup analysis (Analysis 2.8) studies reporting high standards of methods showed a similar effect size as compared to studies with unclear methods. Also, in a sensitivity analysis excluding studies with unclear methods (Analysis 3.10 and Analysis 3.11), the effect sizes did not change substantially. Early terminated studies were not judged to contribute substantial weight to this outcome.

3 Inconsistency: rated 'no' ‐ the P value for heterogeneity was statistically significant and the I2 higher than 50%. However, results of individual studies differed rather in magnitude of effect (which could be partly explained by subgroup analyses) rather than in direction of effect. Therefore, this inconsistency does not challenge the overall results.

4 No indirectness was found in terms of study population nor of interventions. In terms of outcome, we followed the original authors definitions of relapse. These definitions used different criteria, but all addressed symptomatic deterioration related to relapse. Therefore, this was not judged to lead to indirectness.

5 Inconsistency: rated 'no' ‐ the P value for heterogeneity was statistically significant and the I‐square higher than 50%. However, results of individual studies differed rather in magnitude of effect than in direction of effect, which was the same in almost all the studies. Therefore, this inconsistency does not challenge the overall results.

6 Publication bias: it is unlikely that a study was unpublished because of unfavourable data in a secondary outcome. As a possible publication bias had no effect on the results for the primary outcome (relapse at 7 to 12 months), we deem that there was no relevant publication bias for this secondary outcome.

7 Indirectness: hospitalisation due to relapse was our primary interest, but in some studies reasons for hospitalisation were unclearly reported. Overall, we do not deem that this uncertainty was an important source of indirectness.

8 Imprecision: rated 'very serious' ‐ only few studies with few events contributed data to this outcome. The CI was wide, ranging from substantial harm to substantial benefit.

9 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ five out of seven studies were terminated early after interim analyses, possibly leading to overestimation of effect.

10 Indirectness: some rating scales used in the studies have been criticised for eventually not measuring what people understand by quality of life. However, it was decided not to further lower the quality of evidence for this outcome after downgrading for other factors, despite some uncertainty.

11 Imprecise data ‐ only a few studies provided data for this outcome and the confidence interval was large.

12 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ the only three studies included mixed groups of employed and non‐employed participants at baseline, and it is unclear whether employment was supported or competitive employment.

13 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ only three studies contributed to this event which depends on various factors (e.g. the existence of supported employment, rural versus service economy etc).

14 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ eleven out of fifteen studies were terminated early after interim analyses, possibly leading to overestimation of effects.

15 Indirectness: rated 'no' ‐ different rating scales were used in the studies, but this was not judged to challenge the results.

Background

Description of the condition

Schizophrenia is often a chronic and disabling psychiatric disorder. It afflicts approximately 1% of the population worldwide with few gender differences (McGrath 2008). Its typical manifestations are 'positive' symptoms such as fixed, false beliefs (delusions) and perceptions without cause (hallucinations); 'negative' symptoms such as apathy and lack of drive, disorganisation of behaviour and thought; and catatonic symptoms such as mannerisms and bizarre posturing (Carpenter 1994). The degree of suffering and disability is considerable with 80% to 90% of people not employed (Marvaha 2004) and up to 10% dying (Tsuang 1978).

Description of the intervention

Antipsychotic drugs are the mainstay of treatment for schizophrenia. They can be classified according to their biochemical structure (e.g. butyrophenones, phenothiazines, thioxanthenes, etc.), the doses necessary for an antipsychotic effect (high‐potency versus low‐potency antipsychotic drugs), and their risk of producing movement disorders ('atypical' versus 'typical' antipsychotic drugs). What they all have in common is that they block, to a greater or lesser extent, the transmission of dopamine in the brain. Currently there is not a single antipsychotic drug available that is not a dopamine receptor antagonist and the hypothesis that dopamine plays a role in the causation of schizophrenia has been partly derived from the mechanism of action of antipsychotic drugs (Berger 2003). Furthermore, there is no firm evidence that ‐ except for clozapine and possibly some other second‐generation antipsychotic drugs (Kane 1988; Leucht 2009; Leucht 2009a; Leucht 2013; Wahlbeck 1999) ‐ any of these agents is more effective than another (Klein 1969). Early (non‐systematic) reviews (Baldessarini 1985; Davis 1975) have shown that keeping people with schizophrenia on antipsychotic drugs after successful treatment of the acute episode substantially lowers relapse risk, for example, from 53.2% to 15.6% within a period of approximately 9.7 months (Gilbert 1995). Conversely, the side‐effect burden can be considerable, as antipsychotic drugs produce movement disorders, sedation, weight gain and are even related with sudden death. Therefore, clinicians and those with schizophrenia often face a trade‐off between protection against further psychotic episodes and adverse effects.

How the intervention might work

The theory is that schizophrenia is a chronic disorder caused by hyperdopaminergic states in the limbic system (Berger 2003). All antipsychotic drugs block dopamine receptors. Continuous treatment with antipsychotic drugs may be necessary to keep the dopaminergic tone low and to avoid psychotic relapses.

Why it is important to do this review

Although previous reviews had shown that maintenance treatment with antipsychotic drugs reduces relapse rates (Baldessarini 1985; Davis 1975; Gilbert 1995), they did not meet modern systematic review criteria and addressed only one outcome (relapse). The present review is an update of the previous Cochrane Review of Maintenance treatment with antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia (Leucht 2012b). This update is important, because a lot of evidence has emerged since 2012.

Objectives

To review the effects of maintaining antipsychotic drug treatment for people with schizophrenia compared with withdrawing these agents.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We excluded quasi‐randomised trials, such as those where allocation is undertaken on surname. If a trial was described as double‐blind, but it was implied it had been randomised, we included it, but excluded such trials in a sensitivity analysis. Randomised cross‐over studies were eligible but only data up to the point of first cross‐over were used because of the instability of the problem behaviours and the likely carry‐over effects of the treatments (Elbourne 2002).

Types of participants

We included people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia‐like psychoses (schizophreniform and schizoaffective disorders) who had stabilised on antipsychotic medications. There is no clear evidence that the schizophrenia‐like psychoses are caused by fundamentally different disease processes or require different treatment approaches (Carpenter 1994).

Types of interventions

Antipsychotic drugs: any dose or mode of administration (oral or by injection). There is no evidence for large differences in the efficacy of the available antipsychotic drugs (e.g. Davis 1989; Duggan 2005; Leucht 2009; Srisurapanont 2004). All currently available antipsychotic drugs have in common that they act via the blockade of dopamine and their classification according to their chemical properties (e.g. butyrophenones, thioxanthenes or phenothiazines) does not have an important clinical impact. Other classifications into 'low‐ versus high‐potency' or 'typical versus atypical' are continuums, at best (Leucht 2009). We therefore decided to include all antipsychotic drugs that are currently on the market in at least one country.

Active or inactive placebo, or no treatment.

Types of outcome measures

The outcomes were analysed for different lengths of follow‐up: up to three months, four to six months, seven months to one year and more than one year.

Primary outcomes

Relapse at one year (seven to 12 months) as defined by the original studies or by a deterioration in mental state requiring further treatment. Overall relapse and relapse at other time points were considered as secondary outcomes.

Secondary outcomes

The following outcomes were added to the list for this update: number of participants in symptomatic remission, number of participants in sustained remission, number of participants in recovery, social functioning.

1. Relapse

1.1 Across the pre‐specified time periods (please see above). 1.2 Independent of duration

2. Leaving the study early

2.1 Due to any reason (acceptability of treatment) 2.2 Due to adverse events (overall tolerability) 2.3 Due to inefficacy

3. Global state

3.1 Improved (at least minimally) 3.2 In symptomatic remission 3.3 In sustained remission 3.4 In recovery

4. Service use

4.1 Number hospitalised 4.2 Number discharged

5. Death

5.1 Due to any reason 5.2 Due to natural causes 5.3 Due to suicide

6. Suicidal behaviour

6.1 Number with suicide attempts 6.2 Number with suicide ideation

7. Violent/aggressive behaviour

8. Adverse effects

8.1 General: at least one adverse event 8.2 Specific: movement disorders 8.2.1 At least one movement disorder 8.2.2 Akathisia 8.2.3 Akinesia 8.2.4 Dyskinesia 8.2.5 Dystonia 8.2.6 Rigor 8.2.7 Tremor 8.2.8 Use of antiparkinson medication 8.3 Specific: sedation 8.4 Specific: weight gain

9. Satisfaction with care (any published rating scale)

9.1 Participants satisfied 9.2 Carers satisfied

10. Quality of life (any published rating scale)

11. Functioning

11.1 Number in employment 11.2 Social functioning (any published rating scale)

'Summary of findings' table

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2008) and used GRADEPRO to import data from Review Manager to create a 'Summary of findings' table. This table provides outcome‐specific information concerning the overall certainty of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined and the sum of available data on all outcomes that we rated as important to patient care and decision making. We anticipated including the following long‐term main outcomes in a 'Summary of findings' table:

relapse: seven to 12 months;

leaving the study early: due to any reason (acceptability of treatment);

service use: number hospitalised;

death: due to suicide;

quality of life (any published rating scale);

functioning: number in employment;

functioning: social functioning (any published rating scale).

Search methods for identification of studies

No language restriction was applied within the limitations of the search tools.

Electronic searches

Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Study‐Based Register of Trials

On 10 October 2017, the Information Specialist searched the register using the following search strategy which has been developed based on literature review and consulting with the authors of the review:

((*Cessation* OR *Discontinu* OR *Halt* OR *Maintain* OR *Maintenance* OR *Recur* OR *Rehospitali* OR *Re‐Hospitali* OR *Relaps* OR *Stop* OR *Withdr*) in Title OR Abstract Fields of REFERENCE OR (Maintenance Treatment*) in Intervention Field of STUDY) AND ((*Amisulpride* OR *Aripiprazole* OR *Asenapine* OR *Benperidol* OR *Brexpiprazole* OR *Cariprazine* OR *Chlorpromazine* OR *Clopenthixol* OR *Clozapine* OR *Flupenthixol* OR *Fluphenazine* OR *Fluspirilene* OR *Haloperidol* OR *Iloperidone* OR *Levomepromazine* OR *Methotrimeprazine* OR *Loxapine* OR *Lurasidone* OR *Molindone* OR *Olanzapine* OR *Paliperidone* OR *Penfluridol* OR *Perazine* OR *Perphenazine* OR *Pimozide* OR *Quetiapine* OR *Risperidone* OR *Sertindole* OR *Sulpiride* OR *Thioridazine* OR *Thiothixene* OR *Trifluoperazine* OR *Ziprasidone* OR *Zotepine* OR *Zuclopenthixol*) in Intervention Field of STUDY)

In such study‐based register, searching the major concept retrieves all the synonyms and relevant studies because all the studies have already been organised based on their interventions and linked to the relevant topics (Shokraneh 2017).

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major resources (AMED, BIOSIS, CINAHL, ClinicalTrials.Gov, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, WHO ICTRP) and their monthly updates, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses A&I and its quarterly update, Chinese databases (CBM, CNKI, and Wanfang) and their annual updates, handsearches, grey literature, and conference proceedings (see Group’s Module). There is no language, date, document type, or publication status limitations for inclusion of records into the register.

This search was conducted for a broader project and includes studies comparing antipsychotic drugs for relapse prevention (head‐to‐head studies).

On 3 July 2018 first and then on 11 September 2019, a further updated search of the register was performed. The following search strategy, which was also developed consulting with the authors of the review, was used in both cases:

(*{AP}* in Intervention Field of Study) AND ((*Cessation* OR *Discontinu* OR *Halt* OR *Maintain* OR *Maintenance* OR *Recur* OR *Rehospitali* OR *Re‐Hospitali* OR *Relaps* OR *Stop* OR *Withdr*) in Title OR Abstract Fields of REFERENCE OR (Maintenance Treatment*) in Intervention Field of STUDY); {AP} refers to all antipsychotic drugs in the register.

For previous searches, please see Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching

We inspected the references of all included studies and of previous reviews (e.g. Davis 1975; Gilbert 1995) for more trials. The targeted update version of this review performed in 2016 was also inspected (New Reference).

2. Personal contact

We contacted the first author of each included study for missing information and for the existence of further studies.

3. Drug companies

We contacted the manufacturers of antipsychotic drugs and asked them about further relevant studies and for missing information on identified studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For the 2019 search, two review authors (JS, AC) identified and independently inspected citations. For the 2018 search, identified citations were independently inspected by two review authors (AC, JL). For the 2017 search, identified citations were independently inspected by two review authors (among JS, AC and JL). For the original search, two review authors (SL, KK) identified and independently inspected citations. We identified potentially relevant reports and ordered full‐text papers for reassessment. Where disagreements arose we asked a third member of the team for help, and if it was impossible to decide, the full papers were ordered for assessment. This process was repeated for the full papers. If it was impossible to resolve disagreements these studies were added to those awaiting classification and we contacted the authors of the papers for clarification.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

For this update, three review authors (AC, JL, JS) independently extracted data from included studies. For the original review, three review authors (SL, MT, KK) independently extracted data from the included studies. Any disagreement was discussed with another member of the review team, decisions documented and, if necessary, we contacted authors of studies for clarification. The studies included in the original review were closely inspected in order to collect data on the outcomes that were added to the list within the updating process, and to look for potentially new information from eventual recent secondary publications.

2. Management

For the original review, we extracted data onto standard simple forms. For the review update, we extracted data using electronic forms in Microsoft Access.

3. Scale‐derived data

3.1 Valid measures

We included continuous data from rating scales only if: (a) the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000); (b) the measuring instrument was not written or modified by one of the trialists.

3.2 Endpoint versus change data

Since there is no principal statistical reason why endpoint and change data should measure different effects (Higgins 2011, we decided primarily to use scale change data. If change data were not available we used endpoint data. Endpoint and change data were presented in separate subgroups, then pooled in the final analysis.

4. Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, we intended to convert variables that can be reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month).

5. Direction of graphs

Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicates a favourable outcome for maintenance treatment.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Three review authors (AC, JL, JS) for this update and three review authors (SL, MT, KK) for the original review worked independently by using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) to assess trial quality. This set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between overestimate of effect and high risk of bias of the article, such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, other potential sources of bias (i.e. fraud, premature interruption of the studies, baseline clinical imbalances among study groups).

Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted authors of the studies in order to obtain additional information.

We noted the level of risk of bias in the text of the review, the 'Risk of bias' tables and in the Table 1.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Dichotomous data

The review focused on binary data, which are easier to interpret and can be more intuitively understood. For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the random‐effects (Der‐Simonian 1986) risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios (ORs) and that ORs tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). This mis‐interpretation then leads to an overestimate of the impression of the effect. For statistically significant results we calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome/number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome statistic (NNTB/NNTH), and its 95% CI as the inverse of the risk difference (RD).

Where possible, efforts were made to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This could be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. It was generally assumed that if there had been a 20% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, Overall 1962) or the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay 1986), this could be considered as a minimally significant response (Leucht 2005a; Leucht 2005b). If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

2. Continuous data

2.1 Summary statistic

For continuous outcomes we estimated a mean difference (MD) between groups. MDs were based on the random‐effects model as this takes into account any differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. In the case of where scales were judged of such similarity to allow pooling, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD) and, whenever possible, transformed the effect back to the units of one or more of the specific instruments.

All the numbers were entered in a way that a decrease in score should indicate improvement (for change data), and a lower score a better outcome (for endpoint data), in order to provide a similarity to the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, Kay 1986), and make the numbers comparable and easy to interpret. When a rating scale construct provided for a higher score to indicate a better outcome, a minus (‐) was added before the numbers.

2.3 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we applied the following standards to all data before inclusion:

(a) data from studies of at least 200 participants were entered in the analysis irrespective of the following rules, because skewed data pose less of a problem in large studies;

(b) change data: when continuous data are presented on a scale that includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to determine whether data are skewed or not. We entered the study, because change data tend to be less skewed and because excluding studies would also lead to bias, because not all the available information was used;

(c) endpoint data: when a scale starts from the finite number zero, we subtracted the lowest possible value from the mean, and divided this by the standard deviation. If this value was lower than 1, it strongly suggested a skew and the study was excluded. If this ratio was higher than 1 but below 2, there is suggestion of skew. We entered the study and tested whether its inclusion or exclusion substantially changed the results. If the ratio was larger than 2 the study was included, because skew is less likely (Altman 1996; Higgins 2011).

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. First, authors often fail to account for intra‐class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby P values are spuriously low, CIs unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering is not accounted for in primary studies, we presented data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation coefficients (ICCs) for their clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering had been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we present these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the ICCs [design effect = 1 + (m ‐ 1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported it was assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies have been appropriately analysed taking into account ICCs and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies would have been possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in schizophrenia, randomised cross‐over studies were eligible but only data up to the point of first cross‐over.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, especially two appropriate dose groups of an antipsychotic drug, the different dose arms were pooled and considered to be one. Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, we did not reproduce these data.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss to follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). The loss to follow‐up in randomised schizophrenia trials is often considerable calling the validity of the results into question. Nevertheless, it is unclear which degree of attrition leads to a high degree of bias. We did not exclude trials from outcomes on the basis of the percentage of participants completing them. However, we used the 'Risk of bias' tool described above to indicate potential bias when more than 25% of the participants left the studies prematurely, when the reasons for attrition differed between the intervention and the control group and when no appropriate imputation strategies were applied.

2. Dichotomous data

We presented data on a 'once‐randomised‐always‐analyse' basis, assuming an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis. If the authors applied such a strategy, we used their results. If the original authors presented only the results of the per‐protocol or completer population, we assumed that those participants lost to follow‐up would have had the same percentage of events as those who remained in the study.

3. Continuous data

3.1 General

ITT was used when available. We anticipated that in some studies, in order to perform an ITT analysis, the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF) would be employed within the study report. As with all methods of imputation to deal with missing data, LOCF introduces uncertainty about the reliability of the results (Leon 2006). Therefore, where LOCF data have been used in the analysis, they are indicated in the review.

3.2 Missing standard deviations

Where there are missing measures of variance for continuous data but an exact standard error and CI are available for group means, either 'P' value or 't' value are available for differences in mean, we calculated the standard deviation value according to method described in Section 7.7.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). If standard deviations were not reported and could not be calculated from available data, we asked authors to supply the data. In the absence of data from authors, we used the mean standard deviation from other studies.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge clinical heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying people or situations that we had not predicted would arise and, where found, discussed such participant groups or situations.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods, which we had not predicted, would arise and discussed any such methodological outliers.

3. Statistical heterogeneity

3.1. Visual inspection

We inspected graphs visually to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

3.2. Employing the I² statistic

We investigated heterogeneity between studies by considering the I² statistic alongside the Chi² P value. The I² statistic provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance (Higgins 2003). The importance of the observed value of I² statistic depends on both the magnitude and direction of effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from the Chi² test, or 95% CIs for the I² statistic). An I² statistic estimate equal or greater than 50% accompanied by a statistically significant Chi² statistic would be interpreted as evidence of substantial levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2011). When substantial levels of heterogeneity were found in the primary outcome, we explored reasons for heterogeneity (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in Section 10.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar sizes. In other cases, where funnel plots were possible, we sought statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

We employed a random‐effects model for analyses (Der‐Simonian 1986). We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This does seem true to us and the random‐effects model takes into account differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. Therefore, the random‐effects model is usually more conservative in terms of statistical significance, although as a disadvantage it puts added weight onto smaller studies, which can either inflate or deflate the effect size. We examined in a secondary analysis whether using a fixed‐effect model markedly changed the results of the primary outcome.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

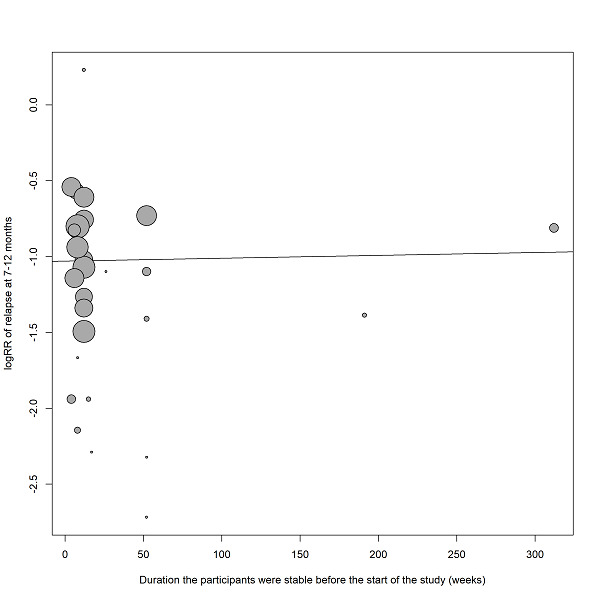

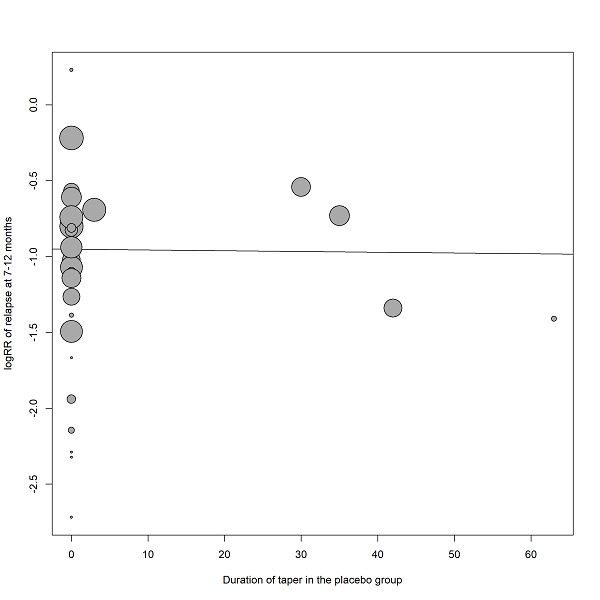

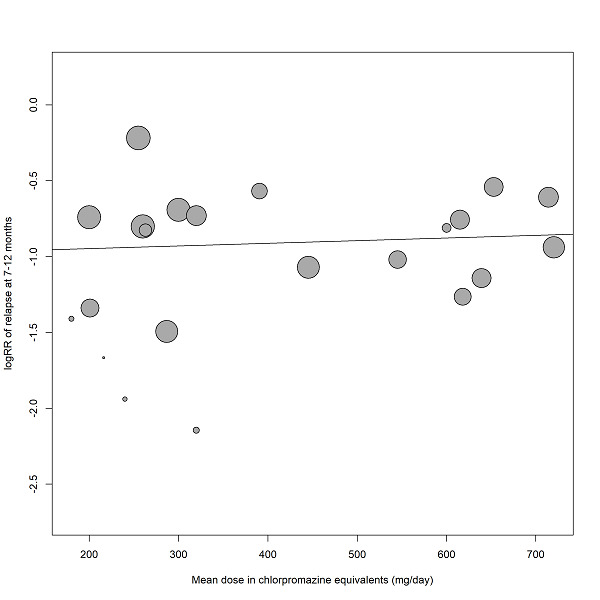

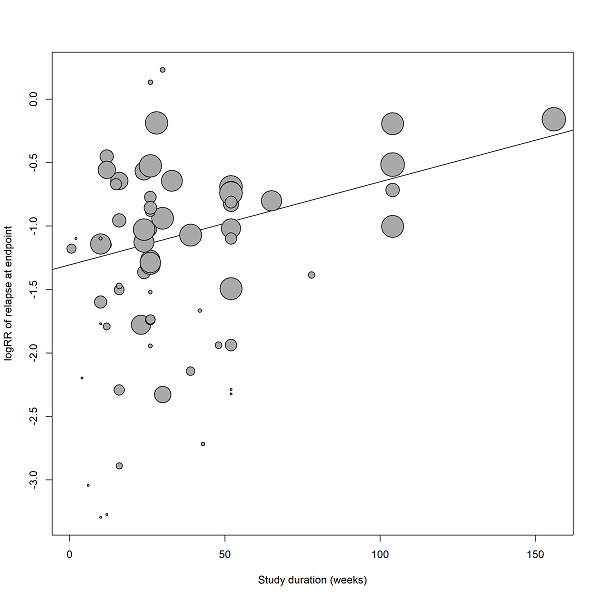

Reasons for heterogeneity in the primary outcome were explored by the following subgroup analyses and restricted‐maximum‐likelihood‐random‐effect meta‐regressions, the latter performed using meta v4.9‐9 (Schwarzer 2007) in R statistical language v3.6.2 (R Core Team 2018). The R code used for meta‐regressions is reported in Appendix 2. Post‐hoc analyses are marked with an asterisk.

Subgroup analyses addressed people with only one episode of schizophrenia and people in remission at baseline, who may both have a better prognosis. We examined people who had been stable for different durations before study entry (at least three, six, nine, 12 and more than 12 months) to find out whether after long‐term stability antipsychotic drugs are no longer necessary. Abrupt versus gradual withdrawal of the pre‐study antipsychotic drug, defined as a minimum taper period of three weeks or depot treatment before the study following Viguera 1997*, was examined because abrupt withdrawal may lead to rebound psychoses. Other subgroup analyses addressed: single antipsychotic drugs*, depot versus oral medication* (depot drugs are thought to be superior due to better compliance), first‐ versus second‐generation antipsychotic drugs* (to address the debate whether the more expensive second‐generation drugs are more efficacious), unblinded versus blinded trials* and studies with appropriate and unclear allocation concealment methods*.

Duration of stability before study entry and duration of taper in the placebo group were also examined by meta‐regressions. Other meta‐regressions addressed severity of illness at baseline, mean dose in chlorpromazine equivalents and study duration. Meta‐regressions were performed only if at least 10 studies per comparison were available (Higgins 2011). For the dose conversion to chlorpromazine equivalents, doses were transferred following the conversion factors provided by available publications (Davis 1974, Gardner 2010, Gopal 2010). Regarding long‐acting injectable drugs, the mean daily dose was obtained by dividing the given dose by the injection interval, and then transferred to chlorpromazine equivalents.

Sensitivity analysis

All sensitivity analyses were made only for the primary outcome. Some of them were performed post‐hoc, due to the fact that reviewers of the original Lancet publication (Leucht 2012a) asked for them.

1. Implication of randomisation

We excluded studies in a sensitivity analysis if they were described in some way as to imply randomisation. If there was no substantive difference when the implied randomised studies were excluded or added to those with better description of randomisation, then all data were employed from these studies.

2. Implication of non double‐blind trials

We excluded trials in a sensitivity analysis if they were not double‐blinded. If there was no substantive difference when the non double‐blind studies were excluded or added to the double‐blind studies, then all data were employed from these studies.

3. Fixed‐effect model

A sensitivity analysis was performed employing a fixed‐effect model for the analysis of data for all the relevant studies, in order to examine whether applying a different approach markedly changed the results of the primary outcome or not.

4. Assumptions for lost binary data

Where assumptions had to be made regarding people lost to follow‐up (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings when we used our assumption compared with completer data only. If there was a substantial difference, we reported results and discussed them but continued to employ our assumption.

5. Inclusion of large studies only

We included trials in a sensitivity analysis only if at least 200 participants were enrolled.

6. Exclusion of studies that used clinical criteria to diagnose the participants

We excluded trials in a sensitivity analysis if either enrolled participants were diagnosed with schizophrenia only on a clinical basis, or no mention to the use of specific operational diagnostic criteria was made.

7. Inclusion of only those participants who had been in the trials without a relapse for specific time intervals

Secondary analyses were performed entering only data of those participants who had not relapsed for various durations after study start (three months, six months, nine months). Relapse risks resulted therefore from the number of relapse events from the beginning at the time interval till the end of a study, divided by the patients at risk of relapse, who had not relapsed before.

8. Exclusion of studies with unclear randomisation/allocation concealment methods

We excluded trials in a sensitivity analysis if a detailed description of the randomisation method used was not provided. In another sensitivity analysis, trials were excluded whether the method of allocation concealment was judged to be inadequately clarified

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Results

Description of studies

For substantive description of studies please see Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Results of the search

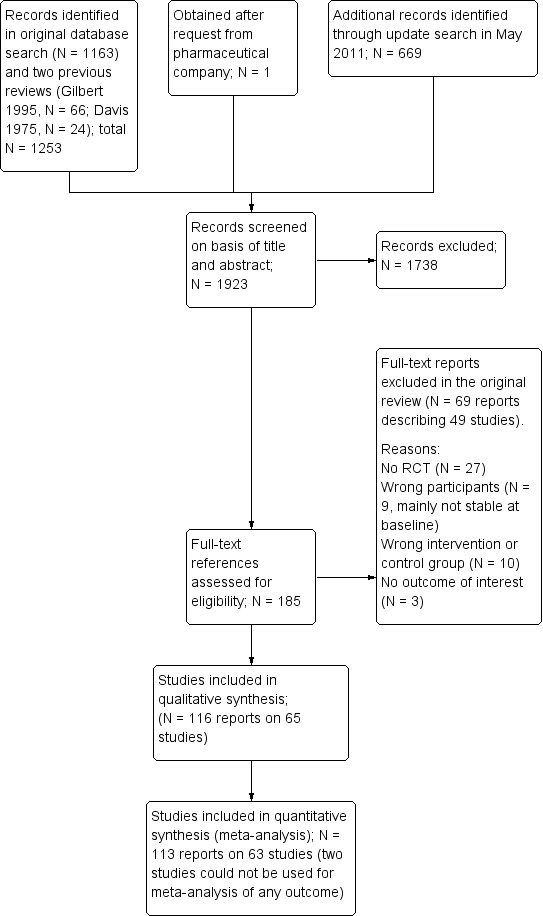

The original search in the CSG register yielded 1163 reports and two previous reviews contained 66 (Gilbert 1995) and 24 studies (Davis 1975). The update search in 2011 identified another 669 reports. Overall, 185 studies were closely inspected. We included 116 publications on 65 studies and we excluded 69 publications on 49 studies. See Study flow diagram (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram (results of the original search)

For the review update in 2018: 3 reports describing the 2 studies originally excluded from quantitative synthesis were moved to excluded studies (no usable data for outcomes of interest); 3 reports on 1 study, originally excluded (short duration of follow‐up), were moved to included studies; one report originally included as independent study was moved as secondary publication of another included study.

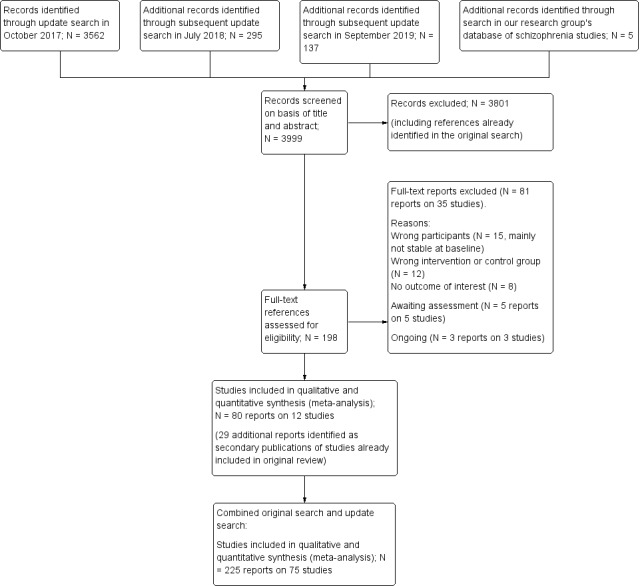

The update search performed in October 2017 yielded 3562 reports; the update search performed in July 2018 yielded 295 reports; the update search performed in September 2019 yielded 137 reports. An additional five reports were identified through other sources (handsearch in our research group's database of schizophrenia trials). Overall, 198 reports were closely inspected within the update process. We included 80 publications on 12 studies, and we excluded 35 studies (81 publications); five reports are still awaiting classification after contacting the corresponding authors, and three reports on three ongoing and potentially relevant trials were also identified. Twenty‐nine reports were moved as secondary publications of already included/excluded studies. See Study flow diagram (Figure 2).

2.

Study flow diagram (results of the 2017/2018/2019 update search and combined results of the original search and the update search)

For this update, one study (originally referenced as 'Pfizer 2000', previously included as an independent study obtained from a pharmaceutical company) was found to be an unpublished report of another included study (Ziprasidone 2002), and was therefore moved into this study; the references reported a slightly different sample size, as one recruiting centre was removed due to protocol deviation, but the reported study ID was the same (128‐303). One study (Olanzapine 1999) was previously excluded due to short duration of follow‐up (one to three days), but was then moved to included studies (a sensitivity analysis of the outcome relapse excluding this study was performed and found no different results); two studies (Gitlin 1988 and Hirsch 1996) were previously included in the qualitative synthesis but not in the meta‐analysis, due to the absence of usable outcome data. For this update, they were moved to excluded studies (see Figure 1).

Overall, 225 publications on 75 studies were included and 150 publications on 85 studies were excluded. See Study flow diagram (Figure 2).

Included studies

Seventy‐five studies (9145 participants) met the inclusion criteria.

1. Length of trials

Of the included studies, 17 had a duration up to three months. Twenty‐six studies lasted up to six months and 25 up to 12 months. Seven studies lasted more than 12 months. The longest study had a duration of three years.

2. Participants

In 33 of the 65 studies, participants were diagnosed according to clinical diagnoses (i.e. specific diagnostic criteria were not mentioned). The others used a variety of tools, combinations of tools and versions of those tools.

| Number of studies | Diagnostic tool | Version | + additional tool |

| 4 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual | II | |

| 5 | III | ||

| 2 | III‐R | ||

| 9 | IV | ||

| 10 | IV‐TR | ||

| 1 | IV Axis I Disorders (Structured Clinical Interview) | ||

| 3 | Present State Examination (PSE) | ||

| 3 | Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) | ||

| 1 | + Schedule for Affective Disorder | ||

| 1 | + PSE + Feighner's criteria | ||

| 1 | Feighner's criteria | ||

| 1 | International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD‐9) | + RDC | |

| 1 | + PSE | ||

The average age of participants was around 45 years old, and the mean duration of illness well over two decades (26.2 years). In 13 studies, participants were in remission at baseline.

3. Setting

Twenty‐nine studies were conducted in hospitals (at least at the start of the trial) and 34 studies in outpatients. Seven studies included both inpatients and outpatients. Several important and [mostly] quite recent studies did not report on setting (Asenapine 2011, Lurasidone 2016, Paliperidone depot1M 2010, Penfluridol 1987, Quetiapine 2007).

4. Study size

The average number of participants was 122 (median 67). Chlorpromazine 1968 was the largest study with 420 participants, while Chlorpromazine 1975 was the smallest, randomising only 14 people. Thirty‐four studies had fewer than 50 participants and 19 randomised more than 200. The oldest trials were some of the largest but, in recent years the size did seem to be increasing (Figure 3).

3.

Size of trial over time

5. Interventions

Seventy‐three studies compared maintenance treatment with antipsychotic drugs and inactive placebo; two open randomised controlled trials (RCTs) compared antipsychotic drugs with no treatment. No data on active placebo as a comparator were available. In most studies flexible doses of antipsychotic drugs were employed although some trials did use fixed doses (see table below). The older trials did have ranges which could have included using doses that would be considered very high now. For example, the doses in Pimozide 1971 and Trifluoperazine 1969 were very high (pimozide 40 mg/day and trifluoperazine 80 mg/day, respectively) and in Various drugs 1982 (chlorpromazine 75 mg/day, haloperidol 3 mg/day) they were very low. However, in most cases most participants would have been given doses of drugs well within the usual ranges employed in current day‐to‐day practice.

| Flexible doses | Fixed doses | ||

| Drug | Dose range | Drug | Fixed doses |

| aripiprazole | 10 mg/day to 30 mg/day | aripiprazole long‐acting | 300 mg or 400 mg four‐weekly |

| brexpiprazole | 1 mg/day to 4 mg/day | haloperidol decanoate | 60 mg four‐weekly |

| cariprazine | 3 mg/day to 9 mg/day | olanzapine | 10 mg/day, 15 mg/day or 20 mg/day |

| chlorpromazine (equivalent) | 50 mg/day to 1000 mg/day | paliperidone depot | 25 mg, 50 mg,100 mg or 150 mg four‐weekly or 175 mg, 263 mg, 350 mg or 525 mg twelve‐weekly |

| flupenthixol depot | 20 mg to 40 mg three‐weekly | zotepine | 300 mg/day |

| fluphenazine decanoate | 1.25 mg to 5 mg twice‐weekly | ||

| fluphenazine depot | 12.5 mg to 25 mg three‐weekly or 25 mg to 50 mg four‐weekly | ||

| iloperidone | 8 mg/day to 24 mg/day | ||

| paliperidone | 3 to mg/day 15 mg/day | ||

| penfluridol | 10 mg/week to 160 mg/week | ||

| perphenazine | 8 mg/day to 24 mg/day | ||

| pimozide | 2 mg/day to 40 mg/day | ||

| prochlorpromazine | 15 mg/day to 150 mg/day | ||

| promazine | 200 mg/day to 400 mg/day | ||

| quetiapine | 500 mg/day to 800 mg/day | ||

| thioridazine | 75 mg/day to 1000 mg/day | ||

| trifluoperazine | 5 mg/day to 50 mg/day | ||

| ziprasidone. | 40 mg/day to 160 mg/day | ||

In a number of studies various antipsychotic drugs could be administered.

6. Sponsor

Most studies had either a neutral sponsor or sponsorship was not indicated. Twenty‐five studies were industry sponsored (Aripiprazole 2003; Aripiprazole 2017; Aripiprazole depot 2012; Asenapine 2011; Brexpiprazole 2017; Cariprazine 2016; Fluphenazine depot 1992; Iloperidone 2016; Lurasidone 2016; Olanzapine 2003; Paliperidone 2007; Paliperidone 2014; Paliperidone depot1M 2010; Paliperidone depot1M 2015; Paliperidone depot3M 2015; Penfluridol 1970; Penfluridol 1974b; Quetiapine 2007; Quetiapine 2009a; Quetiapine 2009b; Quetiapine 2010; Various drugs 1971; Various drugs 1989; Ziprasidone 2002; Zotepine 2000). Frequently medication was provided by the manufacturers of the antipsychotic drugs, but we did not record such studies as primarily 'industry sponsored'.

7. Outcomes

7.1 Relapse

The main relapse criteria in 25 studies was clinical judgement. However, in 24 studies various rating‐scale‐based definitions of relapse were used, in another 16 studies we took relapse as 'need of medication', in four 'admission to hospital', in two 'dropout due to worsening of symptoms', and, finally, in four the criteria used for 'relapse' was not indicated.

7.2 Leaving the study early

The number of participants leaving the study early was recorded by category ('any reason', 'adverse events' and 'lack of efficacy'). In the more recent trials, efficacy‐related adverse events (e.g. exacerbation of psychosis) are often grouped with tolerability‐related adverse events as "Leaving the study early due to adverse events". Where detailed data on leaving early were available, data on 'exacerbation of psychosis' were not entered as 'adverse events'.

7.3 Service use

Service use was described as the number of people re‐hospitalised and the numbers discharged during the trial. When reasons for hospitalisation were provided, we decided to enter data relative to people rehospitalised due to relapse or exacerbation of psychosis.

7.4 Scales

Scales that provided usable data are described below. We had, however, a priori, decided in the protocol to focus on dichotomous outcomes apart from quality of life and social functioning (see Measures of treatment effect). However, a few authors used rating scales to examine extrapyramidal adverse effects and defined cut‐offs to decide whether participants had a particular side effect or not. We used these data and explain below which cut‐offs were used.

7.4.1 Adverse effects scales

7.4.1.1 Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) (Guy 1976) This scale has been used to assess tardive dyskinesia, a long‐term, drug‐induced movement disorder and short‐term movement disorders such as tremor. A low score indicates low levels of abnormal involuntary movements. In Fluphenazine depot 1982, all participants with any positive AIMS score were considered to have tardive dyskinesia. In Olanzapine 2003, the cut‐off was 3 or more on any item, or 2 or more on any two of the items. In Fluphenazine 1980 the cut‐off was any item rated 2. In Quetiapine 2010, the cut‐off was 2 or more on the global severity item.

7.4.1.2 Barnes Akathisia Scale (BAS) (Barnes 1989) The scale comprises items rating the observable, restless movements that characterise akathisia, a subjective awareness of restlessness, and any distress associated with the condition. These items are rated from 0 (normal) to 3 (severe). In addition, there is an item for rating global severity (from 0 (absent) to 5 (severe)). A low score indicates low levels of akathisia. In Olanzapine 2003 all participants with a BAS score of 2 or more were considered to have akathisia. In Quetiapine 2010 the cut‐off was 2 or more on the global severity item.

7.4.1.3 Simpson‐Angus Scale (SAS) (Simpson 1970) The 10‐item scale, with a scoring system of 0 to 4 for each item, measures drug‐induced parkinsonism, a short‐term drug‐induced movement disorder. A low score indicates low levels of parkinsonism. In Olanzapine 2003 all participants with a SAS score of 4 or more were considered to have parkinsonism. In Quetiapine 2010 the cut‐off was 1 or more on the mean SAS score.

7.4.2 Satisfaction with care scales

7.4.2.1 Participant Satisfaction with Medication Questionnaire ‐ Modified (PSMQ‐M) (Kalali 1999)

This self‐administered instrument consists of a 4‐part list of items rated according to 6‐point Likert scales, and measures the patient's satisfaction with current medication (ranging from "extremely satisfied" to "extremely unsatisfied") and the side effects burden (ranging from "no side effects" to "much more side effects"), with respect to previous antipsychotic medications. At the end, the patient is asked to state his preference for "current" versus "previous" medication. This instrument was applied in Aripiprazole depot 2012. The proportion of participants defined by the study authors as "at least very satisfied" was taken into the analysis for the present review.

7.4.2.2 Medication Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) (Vernon 2010)

The instrument consists of a single question, read aloud by the clinician to the patient ("Overall, how satisfied are you with your current antipsychotic medication"). The answer has to be given according to a 7‐point Likert scale, ranging from 1 ("extremely dissatisfied") to 7 ("extremely satisfied). A 1‐point change over time may be considered as clinically meaningful. The proportion of participants defined as "satisfied with medication" according to this instrument was entered into the analysis for the current review, This scale was applied in Paliperidone depot1M 2015.

7.4.3 Quality of life scales

7.4.3.1 Heinrichs‐Carpenter Quality of Life Scale (QLS) (Carpenter 1994) This semi‐structured interview is administered and rated by trained clinicians. It contains 21 items rated on a 7‐point scale based on the interviewer's judgement of patient functioning. A total quality‐of‐life score and four subscale scores are calculated, with higher scores indicating less impairment. This scale was applied in Olanzapine 2003.

7.4.3.2 Symptom Questionnaire of Kellner and Sheffield (SQKS) (Kellner 1973)

The 30‐item self‐completion questionnaire measures subjective well‐being. A total score and four subscale scores are obtainable from the questionnaire. This instrument was applied in Various drugs 1981b.

7.4.3.3 Self‐report Quality of Life Scale (SQLS) (Wilkinson 2000) The scale is a self‐administered rating scale that includes 33 items concerning the patient's symptoms and well‐being over the preceding seven days, on a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (always). Total scores range from 0 to 100, with low scores representing a better outcome. Results based on this rating scale were found in Paliperidone 2007 and Paliperidone depot1M 2010.

7.4.3.4 Schizophrenia Quality of Life (S‐QoL) (Auquier 2003, Boyer 2010)

The scale is a self‐administered questionnaire to assess health‐related quality of life among people with schizophrenia, defined as the discrepancy between expectation and current life experience. The original version is composed of 41 items, and a shortened 18‐item version has been validated, with high degree of comparability with the original one. It is a multidimensional instrument with high reliability, validity and sensitivity to change. It evaluates 8 dimensions (psychological well‐being, self‐esteem, family relationships, relationships with friends, resilience, physical well‐being, autonomy and sentimental life). Each of the items is accompanied by a 5‐point Likert scale (1 = less than expected; 5 = more than expected, with the negatively worded item scores reversed). The score of each of the eight dimensions can be obtained by computing the mean of each item score within the dimension; by summing up every dimension score a total score is obtained. Quetiapine 2009a and Quetiapine 2009b applied this instrument.

7.4.3.5 EuroQol 5 Dimension ‐ Visual Analog Scale (EQ‐5D VAS) (EuroQol 1990)

The EQ‐5D is a self‐administered standardised measure of health status, applicable to a wide range of health conditions, and it is used to evaluate health care from a clinical and economic point of view, as well as in population health surveys. It consists of two parts: the EQ‐5D descriptive system and the EQ 20‐cm visual analogue scale (VAS). The first parts consists of one question in each of five dimensions (mobility, self‐care, pain, usual activities, and anxiety) with five possible response levels per question (level 1= no problem; level 5= extreme problems). The 20‐cm VAS has endpoints labelled "best imaginable health state" (anchored at 100) and "worst imaginable health state" (anchored at 0). Respondents are asked to indicate how they rate their own health by drawing a line from an anchor box to that point on the EQ‐VAS, which best represents their own health on a specified time period (usually that day). This instrument was used in Lurasidone 2016.

7.4.4 Social functioning scales

7.4.4.1 Personal and Social Performance (PSP) (Morosini 2000)

The scale is a validated clinician‐reported instrument that has been widely used in clinical trials to assess personal and social functioning of patients with psychiatric disorders. It is based on four distinct domains: (a) socially useful activities, (b) personal and social relationships, (c) self‐care, (d) disturbing and aggressive behaviour. Each PSP domain is assessed on a 6‐point severity scale ranging from "absent" to "very severe" difficulties in the specified area. After each domain is scored, raters determine one total score by selecting a 10‐point range within a 100‐point scale based on the domain scores following PSP scoring guidelines. The higher the score, the better the functioning. A variation of eight points over time should be classified as clinically significant. This scale was applied in the studies Aripiprazole depot 2012, Brexpiprazole 2017, Cariprazine 2016, Paliperidone 2007, Paliperidone 2014, Paliperidone depot1M 2010, Paliperidone depot1M 2015, Paliperidone depot3M 2015, Quetiapine 2009a and Quetiapine 2009b.

7.4.4.2 Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (American Psychiatric Association 1987)

The scale is a numeric scale (0 to 100 points) used by clinicians to subjectively rate the severity of mental illnesses in terms of their impact on day‐to‐day life. It is a brief and easy‐to‐administer scale, although based on a single global impression. It is broken into 10 sections, so that the higher the score, the better the functioning of the patients. Results derived from this scale were found in Ziprasidone 2002.

7.4.4.3 Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) (Sheenan 1983)

The SDS is a brief, 5‐item self‐administered tool that assesses functional impairment in three areas: work/school, social life and family life. The patient has to rate the extent to which each area is affected by his/her symptoms. Total score is obtained by summing the single dimension score into one measure, and ranges from 0 (unimpaired) to 30 (highly impaired). No cut‐off has been recommended, but a score of 5 or more on any of the three areas could be classified as significant functional impairment. This scale was applied in Iloperidone 2016.

7.4.4.4 Specific Level of Functioning (SLOF) (Schneider 1983)

The scale is a 43‐item multidimensional behavioural survey assessing schizophrenia patients' current functioning and observable behaviour, and it is focused on the person's skills rather than deficits. It can be administered to the patient him/herself or to his/her caregiver. It comprises six subscales: (a) physical functioning, (b) personal care skills, (c) interpersonal relationships, (d) social acceptability, (e) activities of community living and (f) work skills. Each question is rated on a 5‐point Likert scale. Total scores range from 43 to 215, with higher scores representing better overall functioning. This instrument was applied in Lurasidone 2016.

7.4.4.5 Global Assessment Scale (GAS) (Endicott 1976) and Children Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) (Shaffer 1983)

The GAS is a rating scale used to evaluate the overall functioning of a person seeking mental health services, during a specified time period, independently of specific mental health diagnoses. It has proven to have good reliability and high sensitivity to change over time. The scale values range from 1 to 100, with higher scores representing better functioning and scores above 70 indicating good functioning. The CGAS is and adaptation of the GAS, designed to reflect the lower level of functioning of children and adolescents with respect to adults. Fluphenazine depot 1981 reported data from GAS, while the adaptation for children was used in Aripiprazole 2017.

7.5 Other adverse effects

Other adverse events such as death, suicide, suicide attempts, suicidal ideation, violent/aggressive behaviour, at least one adverse event, at least one movement disorder, akathisia, akinesia, dystonia rigor, tremor, use of antiparkinson medication, tardive dyskinesia, sedation and weight gain were reported in a dichotomous manner in terms of the number of participants with a given side effect.

7.6 Global state: number of participants improved (at least minimally)

The number of people who improved at the end of the studies was assessed by the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale (Guy 1976) or similar rating systems. The CGI compares the conditions of the person standardised against other people with the same diagnosis. A 7‐point scoring system is used with low scores showing decreased severity, overall improvement, or both. The outcome was defined as the number of participants 'at least minimally improved' (CGI score of 3 or less). When other scales were used in the original studies (e.g. PANSS, BPRS), data based on the '20% reduction of score' cut‐off were used. If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the numbers presented by the original authors (study‐defined improvement), when available.

7.7 Global state: number of participants in symptomatic remission

The number of participants in symptomatic remission was defined by either 'mild or better' at the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) or similar rating systems, or using the operational criteria for remission in schizophrenia proposed by Andreasen et al (Andreasen 2005), without employing any duration threshold. In this case, a score of 'mild or less' at all eight core symptoms (delusions, hallucinatory behaviour and unusual thought content for the positive dimension, conceptual disorganisation and mannerism/disorders of posture for the disorganisation dimension, blunted affect, social withdrawal and lack of spontaneity/flow of conversation for the negative dimension) constitutes the symptom severity level of remission. If data based on these criteria were not available, other definitions of remission used by the original Authors ‐ with no mention to its duration ‐ were accepted. It should be noted that we defined this outcome as cross‐sectional and representative of the clinical severity level of patients, independent on the fact that the patients were achieving or maintaining it.

7.8 Global state: number of participants in sustained remission

This outcome was defined as either the number of participants achieving and maintaining the aforementioned symptom severity level (symptomatic remission) for a minimum period of six months, as proposed by Andreasen 2005, or the number already in remission at baseline and maintaining the same severity level for the whole duration of the study (if lasting at least six months).

7.9 Global state: number of participants in recovery

At present, more research is needed in order to achieve consensus regarding operational criteria for recovery (Andreasen 2005). Therefore, every definition of recovery provided by the original studies, including symptom severity, social‐occupational functioning and data on subjective recovery, was accepted.

7.10 Number of participants in employment

This outcome was described as the number of participants being employed at the end of the trials.

Excluded studies

We excluded 85 studies. Twenty‐six studies were excluded because they were not (appropriately) randomised. Twenty‐four studies were excluded because they did not examine suitable participants (e.g. participants had not been stabilised on antipsychotic drugs before study start. Twenty‐two studies were excluded because the interventions were not appropriate for this review ‐ most, for example, did not use a placebo control group. Thirteen studies were excluded because they did not report any usable or relevant outcomes.

Risk of bias in included studies

For graphical representations of our judgements of risk of bias please refer to Figure 4 and Figure 5. Full details of judgements are seen in the 'Risk of bias' tables.

4.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

5.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

In 22 studies, random sequence generation was adequate. In the remaining 53 studies this was unclear. Among these, 50 studies were described as "randomised", but 39 of these did not provide any further details about random sequence generation. Eleven studies gave further information about randomisation, but these details were rather superficial and we still had to rate them as 'unclear'. Three further studies (Haloperidol 1973; Penfluridol 1987; Various drugs 1989) did not provide any information about sequence generation, but they were double‐blind and we assumed they were also randomised.

In 26 studies, allocation concealment was rated as adequate. For example, some studies reported that the only people with access to the identity of patients were the hospital pharmacist (e.g. Chlorpromazine 1976; Trifluoperazine 1972), a research assistant (e.g. Fluphenazine depot 1973), a psychiatrist without contact to participants (Various drugs 1962b) or a unit secretary (Various drugs 1971). Aripiprazole depot 2012, Brexpiprazole 2017, Iloperidone 2016Lurasidone 2016, Olanzapine 2003, Paliperidone 2007, Paliperidone 2014, Paliperidone depot1M 2010, Paliperidone depot1M 2015 and Paliperidone depot3M 2015 used an interactive voice‐response system for allocation concealment. One study (Ziprasidone 2002) used treatment cards numbered for each participant and investigators and pharmacists allocated numbers to people. Quetiapine 2010 reported that AstraZeneca prepared individually‐numbered study drugs and packed them according to the randomisation sequence. Two studies mentioned that codes were not broken until the time of the analysis and that the code was unknown to the investigators (Haloperidol depot 1982, Zotepine 2000).

The remaining 49 studies ‐ often undertaken well beyond the period when the need for good reporting was widely recognised (CONSORT) ‐ did not provide any details on allocation concealment. Therefore, it was unclear for most of the studies whether adequate allocation concealment methods were used.

Blinding

Concerning bias related to blinding of participants and personnel, we rated seven studies to have a low risk of bias. In them it was either tested that blinding had worked (Chlorpromazine 1962; Fluphenazine depot 1973; Perphenazine 1963; Various drugs 1971), or the authors had applied specific measures to improve blinding (e.g. prophylactic antiparkinson medication to avoid unmasking by side effects, Fluphenazine 1979; medication was administered by a person distinct from other study personnel, Paliperidone depot1M 2015 and Paliperidone depot3M 2015).

Six studies were rated with a high risk of bias. Various drugs 2011 was an open study, without providing any further information. In Various drugs 1964a, the placebo group received medication only every other day and blinding was not fully maintained. Various drugs 1968 and Various drugs 1981a reported that nurses had made correct guesses as to who was on drug and who was on placebo. In Fluphenazine depot 1982 evaluating psychiatrists and participants were unaware of the contents of the injections, while treating psychiatrists seemed to be aware of it. Various drugs 1993 was an open trial with rating scales being additionally rated by a second blind assessor.

In the other 62 studies, we rated the risk of bias as unclear. All these studies were described as double‐blind, with no further relevant information.

Concerning blinding of outcome assessment, all studies were rated as 'low risk of bias' concerning what we designated as 'more' objective outcomes, because we considered blinding to be less important for these.

As to subjective outcomes, we rated seven studies to have a low risk of bias. In them it was either tested that blinding had worked (Chlorpromazine 1962; Fluphenazine depot 1973; Perphenazine 1963; Various drugs 1971) or the authors had applied specific measures to improve blinding (e.g. prophylactic antiparkinson medication to avoid unmasking by side effects, Fluphenazine 1979; medication was administered by a person distinct from other study personnel, Paliperidone depot1M 2015 and Paliperidone depot3M 2015).

Four studies were rated with a high risk of bias for subjective outcomes. Various drugs 2011 was an open study, without providing any further information. In Various drugs 1964a, the placebo group received medication only every other day and blinding was not fully maintained. Various drugs 1968 and Various drugs 1981a reported that nurses had made correct guesses as to who was on drug and who was on placebo.

In the other 64 studies, we rated the risk of bias for subjective outcomes as 'unclear'. With the exception of Various drugs 1993 (an open trial with rating scales being additionally rated by a second blind assessor), all these 64 studies were described as double‐blind. But as antipsychotic drugs have adverse effects we considered that we should make a conservative judgment about the success of blinding. Many of these reports did not provide any details about how double‐blind conditions were maintained. It was usually just stated that the studies were "double‐blind" or it was simply indicated that "identical capsules" were used. Some studies using depot antipsychotic drugs reported that sesame oil injections were used in the placebo groups (e.g. Fluphenazine depot 1968 and Various drugs 1984a).

Incomplete outcome data

The number of participants leaving the studies early was frequently high leading to a judgement of high risk of bias in 30 included studies. The most frequent reason for leaving the studies early was 'relapse', because many studies had predefined in their protocols that once participants had relapsed they had to discontinue the trial. This had two consequences: the primary outcome relapse was frequently not affected by attrition, because most participants reached this end point. However, there was a risk of bias for other outcomes (e.g. adverse effects), because the reasons for leaving the studies early differed between participants on placebo (mainly relapse/inefficacy) and participants on antipsychotic drugs (other reasons).

Only 19 studies used survival analyses to examine relapse rates, while most others simply counted the numbers of participants who relapsed. We, therefore, had to restrict this review to analysis of relapse rates rather than more sensitive parameters such as 'time to relapse'.

Selective reporting

We judged 63 studies to be free of selective reporting. However, many did not (sufficiently) report on predefined outcomes.

| Studies with insufficient reporting of pre‐defined outcomes |

| Aripiprazole 2003, Haloperidol 1991, Iloperidone 2016, Lurasidone 2016, Olanzapine 2003, Penfluridol 1970, Penfluridol 1974c, Quetiapine 2007, Quetiapine 2009a, Quetiapine 2009b, Various drugs 1962a, Zotepine 2000, |

Other potential sources of bias