Abstract

Despite the exponential growth of crowdfunding in recent years, research on the role it plays in business internationalization is still embryonal. Building on the Resource Based View (RBV) and Knowledge Based View (KBV), this study explores how SMEs can use equity crowdfunding (ECF) and reward crowdfunding (RCF) to internationalize and the related potential limitations. Using an inductive qualitative research design, based on multiple case studies of Italian SMEs, our study showed that ECF and RCF models help SMEs in acquiring the financial resources needed to internationalize and, at the same time, offer significant added value to their internationalization. Our findings support the idea that ECF and RCF play a key role in helping companies to overcome their resource limitations in regard to internationalization, not only in terms of the provision of financial resources but, above all, by compensating for any lack of knowledge on aspects relevant to the internationalization process. Furthermore, our results show the limitations of SMEs use of crowdfunding in order to internationalize (i.e., a lack of ad hoc e-commerce policies in relation to equity crowdfunding and to the regulation of the pre-ordering mechanism in the reward model). This paper concludes by discussing the theoretical and managerial contributions to the international business domain, and highlighting fruitful avenues for future studies.

Keywords: Equity crowdfunding, Reward crowdfunding, Internationalization, SMEs, International business, Financial resources, E-commerce policy

Introduction

Internationalization is a phenomenon that has been explored extensively over the years with a focus on both large and small/medium enterprises (SMEs). The similar international issues faced by both types of companies mean that, for them, “it is no longer possible to act in the marketplace without taking into account the risks and opportunities presented by foreign and/or global competition” (Ruzzier et al., 2006, p. 476).

In general terms, SMEs commonly need to overcome several obstacles to internationalize (e.g., a lack of financial support, partners, and legislative/regulatory prescriptions). Specifically, these criticalities are also faced by European SMEs (European Commission, 2019). In this regard, an increasing body of literature indicates that SMEs – that during the last decade have seen a remarkable development – are of major importance for European macroeconomic growth (e.g., Hervás-Oliver et al., 2021; Mateev et al., 2013). The cause of these criticalities is often identified in a cultural fragmentation that makes it difficult to provide SMEs with a uniform support suited to help them overcome the main barriers – such as a lack of knowledge, capabilities, networks/relationships, specialized personnel, and, above all, adequate resources (Singh et al., 2010). Notably, most SMEs are still tied to traditional forms of financing that do not favor internationalization and do not provide any benefits other than funds (e.g., banks and government support initiatives). Furthermore, compared with large companies, SMEs are characterized by non-negligible resource constraints (Chan et al., 2019) and, often, by a lack of experience (Lu & Beamish, 2001) and knowledge on key aspects (e.g., market strategies), which is a crucial issue for them in this field (Schweizer, 2012).

These limitations are compounded by the uncertainty and complexity that characterize the dynamic international environment (Hagen et al., 2019). This challenging and fast-changing scenario requires companies to be open (Di Pietro et al., 2018) and transformative, and to proactively adopt new technological solutions, such as digital platforms, in order to integrate their traditional competencies with digital knowledge and to develop and sustain key advantages (Schiuma et al., 2021). SMEs, which are increasingly internationalizing their activities, are now considered active players in the related processes (Ruzzier et al., 2006; Schweizer, 2012); hence, they need to embrace change and consider the adoption of new technologies as a valuable opportunity to increase their competitiveness and to foster their internationalization (e.g., Chen et al., 2019; Dabić et al., 2020; Zeng et al., 2019). Digital technologies enable faster internationalization, in particular for their recent advancements and cost reductions (e.g., Fischer & Reuber, 2011; Oviatt & McDougall, 2005; Pergelova et al., 2019). Such technologies facilitate the connection of SMEs with different stakeholders (Fischer & Reuber, 2011), increase the efficiency of information exchange (Mathews & Healy, 2008), and, according to Pergelova et al., (2019, p.14), have the potential to provide “access to international market knowledge and facilitating interactions with customers and partners”, thus disclosing their function of democratizing entrepreneurship. At the same time, such powerful democratizing function plays a key role in lowering traditional market entry barriers, as it enables a multitude of diverse people to engage in international market exchanges (Aldrich, 2014; Nambisan, 2017).

Digital platforms thus have the potential to accelerate the internationalization of companies as well as their expansion and the commercialization of opportunities in foreign countries. Furthermore, it is important to underline that such platforms enable the connection of geographically dispersed entrepreneurs and investors (Maula & Lukkarinen, 2020; Nambisan et al., 2019). In particular, crowdfunding platforms have recently been established in many countries (e.g., Belleflamme et al., 2015; Kraus et al., 2016; Troise and Tani, 2021; Vrontis et al., 2021). Block et al. (2018) defined crowdfunding as a new player in the global arena, one that helps entrepreneurs in overcoming their difficulties in raising funds. Crowdfunding platforms enable entrepreneurs and firms to involve large pools of backers/investors, to connect with different people, and to raise funding from the crowd, rather than from (few) professional investors such as venture capitalists (VCs) and private equity (PE) investment funds (e.g., Belleflamme et al., 2014; Mollick, 2014; Vismara, 2016, 2018).

In this regard, crowdfunding represents an effective alternative to VCs and business angels (BAs); however, unlike the other two, it “has thus far not received attention in the international entrepreneurship literature” (Maula & Lukkarinen, 2020, p.2). For example, some studies have focused on the role VCs play as ‘catalysts’ of company internationalization by providing resources such as knowledge (related to international expansion strategies), as well as by affecting the strategic directions of the firms in which they invest (e.g., Fernhaber & McDougall-Covin, 2009; Mäkelä & Maula, 2005; Park & LiPuma, 2020). Recent studies have shown that these characteristics are shared with crowdfunding, as the crowd also influences the trajectories of the companies in which they invest (Troise et al., 2021b) and provides a new stock of knowledge through crowd inputs (Di Pietro et al., 2018; Troise and Tani, 2021). It is well-known that knowledge plays a fundamental role in company internationalization (Autio et al., 2000) and that investors possess different knowledge bases (Maula et al., 2005). Crowdfunding offers a unique mechanism by enabling companies to gain non-financial benefits and new knowledge from a large number of investors. The crowd of investors, in fact, possesses a variety of experiences and backgrounds, thus ensuring a unique selection mechanism that is superior to that of any single individual, even an expert. Notably, a “crowd displays more wisdom than an individual” (Walthoff-Borm et al., 2018, p.315). Troise and Tani (2021) showed that entrepreneurs approach crowdfunding strategically to obtain additional benefits – other than funds – through crowd engagement. Companies, in fact, can thus leverage the knowledge and skills of a large number of investors/backers. Companies can exploit crowd networks – i.e., by accessing strategic networks (in terms of establishing partnerships or developing relationships with stakeholders) and increasing public awareness – and knowledge (in terms of strategies, products, and markets) (Di Pietro et al., 2018). Di Pietro et al. (2018) highlighted that such exploitation helps companies to internationalize and is crucial to speeding up the international expansion of those companies that have used equity crowdfunding (ECF).

Several scholars of international entrepreneurship have highlighted the importance of decision-makers evaluating and exploiting new opportunities to internationalize (e.g., Lu & Beamish, 2001; Oviatt & McDougall, 1994, 2005; Schweizer, 2012; Wright & Ricks, 1994). Technological advances may open up internationalization opportunities to companies and tap foreign markets (Oviatt & McDougall, 2005). The choice to use crowdfunding is part of the strategic decision-making process of entrepreneurs, as they may decide to approach new technologies and systems to obtain further resources and/or for other purposes (Troise and Tani, 2021). Interestingly, crowdfunding can be strategically adopted to internationalize.

Despite the recent exponential growth of crowdfunding and the potential enabling effect of crowdfunding platforms for SME internationalization (Cai et al., 2021; Martínez-Climent et al., 2018; Mochkabadi & Volkmann, 2018; Moritz & Block, 2016), very little is known on its possible use for purposes other than fundraising and, in particular, to facilitate entrepreneurial internationalization (Cumming & Johan, 2016; Shneor & Maehle, 2020).

Accordingly, scholars presently have limited knowledge of the role played by crowdfunding in business internationalization, and the ways in which this new player can enable them to enhance or initiate this process and/or bypass traditional systems and channels remains unclear. Hence, the lack of prior research in this field represents a major gap in the existing literature. To remedy this state of affairs, there is an ongoing call for further research to be conducted in this research stream (Cumming & Johan, 2016), which has hitherto only been addressed by some sporadic studies (e.g., Di Pietro et al., 2018).

Adding to this, and to the best of our knowledge, little attention has also been paid to SMEs, despite such companies increasingly resorting to crowdfunding, of which they are target (Troise et al., 2020a, b). Unlike multinational corporations, SMEs have traditionally been considered local firms, i.e., companies the activities of which mainly take place within national boundaries (Pleitner, 1997); however, technological advances have facilitated their global access (Dabić et al., 2020) and crowdfunding platforms represent an intriguing opportunity for them to overcome traditional barriers and access key resources – such as any missing knowledge – thus compensating for their shortcomings.

Our study was aimed at filling these gaps in the literature by exploring how SMEs can use ECF (Ahlers et al., 2015; Troise et al., 2020b, 2021b; Vrontis et al., 2021) and reward crowdfunding (RCF) (Davis et al., 2017; Mollick, 2014) to internationalize, and the connected potential limitations (Politecnico of Milan, 2020; Troise et al., 2020b). Our choice of these two types of crowdfunding systems (which is specifically explained in the next section) is related to their nature and utility compared to other models (e.g., lending and donation crowdfunding).

Hence, our study was guided by and aimed at answering the following two research questions:

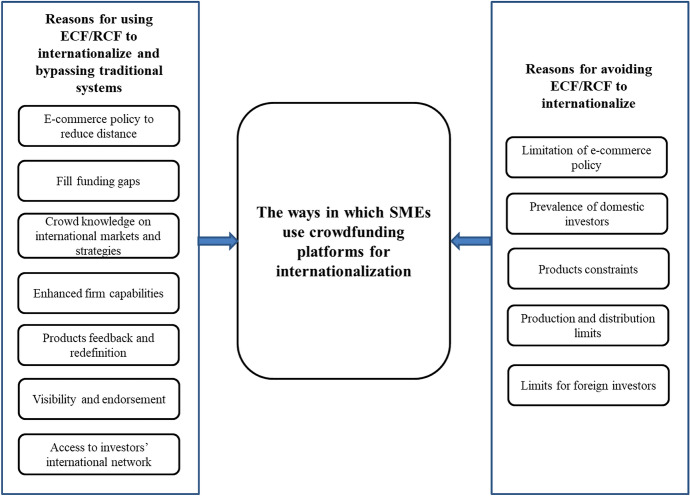

RQ1: How can SMEs use equity and reward crowdfunding to internationalize, and bypass traditional systems/channels?

RQ2: What are the limitations related to the use of equity and reward crowdfunding by SMEs to internationalize?

In order to address these research questions, we adopted an inductive qualitative research design, based on multiple case studies of Italian SMEs. Our primary data were collected through semi-structured interviews conducted with CEOs, while the secondary data were collected through several other sources (such as social media and platform and company websites). In particular, we considered the Italian SMEs as our research context for four main reasons. First, Italy is characterized by the predominance of SMEs (e.g., Perrini, 2006). Second, given the relevance of SMEs for the Italian economy, the Italian government pays attention to their internationalization, and it strives to support this scope through specific actions (e.g., the Law n. 58–2019). Third, researchers emphasized that the internationalization of Italian SMEs represents a remarkable research area and they tried to explore how these specific firms pursue internationalization (e.g., Festa et al., 2020). Fourth, following some prior studies (e.g., D’Angelo et al., 2013), our attention on Italian SMEs is a possible response to appeal of Barney et al. (2011) for more research on firms smaller and different from Multinational Enterprises, by adopting the Resource Based View lens.

In general terms, the findings of our study support the idea that equity and reward crowdfunding play a key role in helping companies to overcome their resource limitations in regard to internationalization but also show the limitations of SMEs use of crowdfunding in order to internationalize.

These results lead to the following theoretical and managerial contributions. First, our study contributes to the current debate to the international business domain on the role of crowdfunding in facilitating company internationalization (Cumming & Johan, 2016). Second, our research highlights the relevance of crowdfunding in compensating for any resource constraints faced by SMEs by providing not only financial resources but also new exploitable knowledge and networks (Di Pietro et al., 2018; Troise and Tani, 2021). Third, our study contributes also to the emerging literature on open innovation (OI), which recently has started to explore crowdfunding platforms (Di Pietro et al., 2018). Finally, our findings can offer valid implications for policymakers, governments, and authorities because these important actors could encourage SMEs to use ECF and RCF to internationalize, while striving to overcome the limitations currently affecting these systems (i.e., a lack of ad hoc e-commerce policies in relation to ECF model and to the regulation of the pre-ordering mechanism in the RCF model).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In the next two sections, we present the literature review and the theoretical considerations followed by the methodology. The fourth section reports the main findings, while the following one provides a discussion of the findings. The last section refers to the theoretical and managerial implications of our study, and states its limitations as well as various avenues for further research.

Literature Review and Theoretical Considerations

SMEs’ Internationalization

Over the years, SMEs assumed a great relevance in most economies and, in fact, they play a key role in the economic development of the countries (La Rovere, 1998; Ormazabal et al., 2018). These companies are essential to the competitiveness, innovativeness and prosperity of countries and contribute significantly to their GDP, as well as creating numerous job opportunities (Paul et al., 2017). Considering the specific European context, SMEs have a significant impact on the EU economy (Triguero et al., 2016; European Commission, 2020), and in this regard the European Commission (2020) highlighted that: “SMEs are the backbone of Europe's economy. They represent 99% of all businesses in the EU. They employ around 100 million people, account for more than half of Europe’s GDP and play a key role in adding value in every sector of the economy. SMEs bring innovative solutions to challenges like climate change, resource efficiency and social cohesion and help spread this innovation throughout Europe’s regions…”.

Given this importance of SMEs, countries pay close attention to increasing the international activities of their SMEs – i.e., to foster the geographical expansion of these activities over the border of the national country – to stimulate economic growth, and to obtain additional benefits such as reducing unemployment (Ruzzier et al., 2006).

Internationalization represents a form of geographic diversification and a strategic behavior of the SME. It is a key and strategic choice of these companies to increase their competitiveness and ensure their survival (Colapinto et al., 2015; Coviello & Martin, 1999). The debate on SMEs and internationalization dates back to more than 40 years ago, and has since been the subject of increasing attention (Dabić et al., 2020). For SMEs – which traditionally have inadequate financial bases, a domestic focus, and restricted geographic scopes – international expansion represents an important and critical decision (Lu & Beamish, 2006). Specifically, internationalization can help entrepreneurial initiatives to develop and increase their performance (Sapienza et al., 2006). Literature shows several drivers to internationalization, such as those linked to the experiences of foreign partners and the customer followership or niche markets (e.g., Bell, 1995). According to the bibliometric and systematic review by Dabić et al. (2020), among the great variety of motivational factors that explain the internationalization of SMEs, the most important is the need for entrepreneurs to have a ‘global mindset’. On the other side, there are different barriers SMEs face to internationalize, particularly of a religious and ethnic nature (Pangarkar, 2008). In this vein, other main factors identified by previous studies are intellectual property rights, telecommunications/digital infrastructures, political risks, competition policy and legislative/regulatory frameworks (Singh et al., 2010).

SMEs face significant challenges and constraints to exporting, such as limited financial resources and incomplete foreign market information and contacts (Paul et al., 2017; Ruey-Jer & Daekwan, 2020). The international entrepreneurship literature relating to SME internationalization has investigated many aspects – such as the timing, the approach, and the intensity and sustainability of internationalization, the influence of the domestic environment on internationalization, the effect of internationalization on performance, and the use of external resources to internationalize (Wright et al., 2007). With reference to the last point, VCs represent a typology of consolidated financial intermediaries that invest in privately held firms that are usually small and young (e.g., Smolarski & Kut, 2011). From this perspective, the traditional resource stocks of VCs, not only in terms of equity-based capital, play an important role in the internationalization process of these companies because these institutional investors can provide the knowledge needed to facilitate internationalization (Park & LiPuma, 2020). For example, the knowledge possessed by foreign VCs facilitates the expansion of the financed firms into their home countries (Park & LiPuma, 2020).

Recently, crowdfunding entered the global arena (Block et al., 2018) and it represents not only an alternative to traditional fundraising systems (e.g., VCs and BAs), but also a strategic choice for SMEs to get additional (financial and non-financial) resources and (missing) knowledge (Troise and Tani, 2021). Aside from the VCs discussed above, BAs are useful sources of finance for SMEs, however Macht and Weatherston (2014) pointed out that crowdfunding has several additional advantages for companies over BAs. Through crowdfunding, companies can launch online calls and quickly reach a large crowd of investors – without geographical constraints – instead of a few of sophisticated investors (Belleflamme et al., 2014; Mollick, 2014). This large pool of investors provide involvement in the businesses in which they invest as well as their knowledge or skills, i.e., the so-called ‘wisdom of the crowd’ (Walthoff-Borm et al., 2018). The use of crowdfunding allows companies to avoid the loss of control or ownership, as they – in the case of the ECF – can decide the amount of equity to sell (Ahlers et al., 2015; Troise and Tani, 2021).

In a constantly evolving context, the Internet is regarded as a crucial innovation for SME internationalization and Internet platforms – including crowdfunding platforms, which allow companies to make online calls to raise funds – offer fast early-stage funding opportunities (Mollick, 2014; Vismara, 2016). Previous studies have highlighted the benefits (e.g., Hamill & Gregory, 1997; Samiee, 1998) and risks (e.g., Houghton & Winklhofer, 2004) related to the use of the Internet. Specifically, recent literature on international business has highlighted the importance of the network effect in explaining the internationalization and cross-border activities of platform-based firms (e.g., Brouthers et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2019; Zeng et al., 2019). In this regard, the role played by digitization in shaping the current business landscape is gaining growing recognition and importance in relation to economic development (Zeng et al., 2019). The study of Eduardsen (2018) highlighted that digitalization influences the internationalization of SMEs and, in fact has shown a higher degree of internationalization from the SMEs using the Internet and that e-commerce can also facilitate this internationalization of SMEs.

Digital platforms are enablers for the internationalization of the SMEs, as they facilitate the interaction with global players and access to their knowledge (Pergelova et al., 2019). Crowdfunding platforms favor the connection for SMEs with crowd-investors from various countries (Maula & Lukkarinen, 2020) and reduce the traditional geographic constraints (Mollick, 2014). The added-value of crowdfunding platforms, in this sense, is that they connect investors with companies, overcoming these limits; at the same time, these platforms act as intermediaries, and the companies make online calls to raise funds, although the virtual environment limits direct interactions between the parties (Troise et al., 2021a).

The use of crowdfunding is currently a strategic choice for SMEs as it allows them both to obtain financial resources for their internationalization process and, at the same time, helps them to acquire new knowledge from a large crowd of backers/investors (Di Pietro et al., 2018; Troise and Tani, 2021). These characteristics make crowdfunding particularly interesting to be studied in relation to the internationalization of SMEs that are characterized by the aforementioned constraints and barriers.

Crowdfunding

The concept of crowdfunding derives from the concept of crowdsourcing and according to Belleflamme et al., (2014, p. 588) it “involves an open call, mostly through the Internet, for the provision of financial resources either in the form of donation or in exchange for the future product or some form of reward to support initiatives for specific purposes”. Crowdfunding is a relatively new outlet for capital acquisition as it allows entrepreneurs to raise funds for their ventures directly from the crowd, i.e., a large audience of unsophisticated investors who supports initiatives with relatively small amounts of funds, through Internet-based platforms without resorting to traditional financial intermediaries or sources (Mollick, 2014).

Crowdfunding is currently booming thanks to the growth in Internet use and the spread of dedicated platforms around the world. To date, it represents a valuable and increasingly important alternative to finance SMEs (Giudici & Rossi-Lamastra, 2018), and plays a vital role in helping companies to overcome funding difficulties and fill their funding gap (i.e., their shortage of capital) (Macht & Weatherston, 2014). This occurs especially when some businesses are not attractive to other sophisticated investors – for example based on financial metrics – given the company’s short track record or the uncertainty surrounding the initiative and its developments.

Several studies have shown that crowdfunding is of great importance for companies as it provides them with significant benefits, in addition to those of a monetary nature (Di Pietro et al., 2018; Estrin et al., 2018; Macht & Weatherston, 2014; Wald et al., 2019). Firstly, it assumes relevance for the ‘provision of contacts’ (Macht & Weatherston, 2014), as the company will benefit from increased publicity resulting from the public exposure of the business and products generated by the crowd of investors (Di Pietro et al., 2018; Estrin et al., 2018). Through crowdfunding, it is possible not only to increase awareness of the company or the product (Estrin et al., 2018), but also access to valuable networks (Troise and Tani, 2021). Network exploitation is a key activity to develop relationships with key stakeholders (Di Pietro et al., 2018). Similarly, the large pool of investors allows companies to leverage and exploit crowd knowledge. Companies benefit from the knowledge of the crowd and obtain non-financial feedback/inputs from large number of individuals, in particular in reference to those related to product, service and market (Di Pietro et al., 2018). Finally, given these exposure and awareness, crowdfunding can facilitate further funding opportunities (Macht & Weatherston, 2014).

More and more SMEs use crowdfunding to raise funds and overcome the unavailability of traditional financing (Giudici & Rossi-Lamastra, 2018; Troise et al., 2021a). Generally, SMEs are known to be less equipped than large companies to address the challenges and barriers to their internationalization discussed above. Both resources constraints and limited knowledge represent critical issues for their internationalization (Chan et al., 2019; Paul et al., 2017; Singh et al., 2010).

According to the Resource Based View (RBV) (Barney, 1986, 1991), the sustainable competitive advantage of companies builds on the resources they can get access to (Dyer & Singh, 1998; Peteraf, 1993). The resources mobilized – or which can be mobilized – by SMEs, as well as their accessibility, have significant effects on their international growth and their ability to enter new markets (Andersen & Kheam, 1998; Westhead et al., 2001).

Companies benefit from the use of external resources (Wright et al., 2007) as well as from external relations to access their resources and their knowledge (Dyer et al, 2018; Ireland et al., 2002). Among the limited resources of SMEs, compared to large companies (Chan et al., 2019), knowledge represents the most critical (Grant, 1996). As highlighted by Knowledge Based View (KBV), knowledge plays a crucial role for companies, which are institutions that mainly integrate knowledge. The exploitation of knowledge enables companies to establish an international competitive advantage (Kundu & Katz, 2003; Zahra et al., 2003) and to overcome any initial and crucial liabilities – e.g., those of smallness (or newness) (Stinchcombe, 1965) and of foreignness (Zaheer, 1995). Any scarcity of resources (or competencies) can thus be overcome and/or compensated by a greater openness to the use of external sources of knowledge (Alvarez & Barney, 2001; Christensen et al., 2005). This openness may be crucial for companies, especially small ones, to access any required or missing key resources (Chesbrough et al., 2006) and to accelerate their internationalization process. Recent studies have found that crowdfunding enables SMEs to become open to the crowd’s knowledge (Di Pietro et al., 2018; Troise and Tani, 2021). Crowdfunding platforms are thus emerging open innovation (OI) tools adopted by companies to address any challenges related, for example, to sustainability, commercialization opportunities, and internal innovation processes (Di Pietro et al., 2018; Troise et al., 2021b). Similarly, we argued that crowdfunding can also help companies to address internationalization challenges. It can represent a strategic option for SMEs to gain resources and knowledge to internationalize.

In the current global scenario, crowdfunding can represent an important source of international capital (Cumming & Johan, 2019) and provide entrepreneurs with a chance to approach and exploit networks across countries and regions to fundraise (e.g., Dejean, 2020; Di Pietro & Masciarelli, 2021). During the last decade, fundraising has also significantly changed thanks to this type of innovative instrument (e.g., Giudici et al., 2013; Zhao & Ryu, 2020), which represents a source of funding that plays a progressively more important role in the financing of entrepreneurial firms (Walthoff-Borm et al., 2018). In crowdfunding platforms, technological innovation overcomes any distance-related resistance through three main features: ease of search, less need for monitoring, and information on what others have done (Agrawal et al., 2015). In recent years, some scholars have explored how and to what extent entrepreneurial internationalization is facilitated by crowdfunding (e.g., Cumming & Johan, 2016, 2019; Shneor & Maehle, 2020). However, in the literature, there is no direct empirical evidence for whether crowdfunding matters for international trade (Cumming & Johan, 2019). Nevertheless, an important indirect evidence is that provided by Suominen and Lee (2015), who showed that the advanced constraints or obstructions faced by smaller companies are associated not only to financing, but also to cultural and language barriers, difficulties in locating sales targets, and finding foreign partner firms. These problems can be mitigated by crowdfunding due to the potential advantage stemming from the global provenance of the investors and entrepreneurs who engage in it. In this regard, Cumming and Johan (2016) highlighted that the exponential development of crowdfunding and its associated growth in trust facilitate the ability of entrepreneurs to use it to internationalize; this is because crowdfunding can facilitate control over adequate resources, which is an important component of entrepreneurial firm internationalization. In particular, crowdfunding enables firms to directly gain traction in consumer markets around the world, even across vast distances. Moreover, crowdfunding platforms can support SMEs with market intelligence and provide local knowledge appropriate to the internationalization of services and products (Cumming & Johan, 2019). However, Agrawal et al. (2015) argued that, although the Internet reduces any distance-related friction, online transactions in crowdfunding campaigns are nevertheless influenced by geographic distance and are more likely to occur between buyers and sellers from the same geographic region. In any case, the chance to gain insights or information about entrepreneurial firms is the same for all investors, independently of geographic distance. In this regard, Guenther et al. (2018) highlighted that geographic distance is negatively correlated with investment possibility for all home country investors. Furthermore, some studies have also highlighted the effect of cultural differences between countries in relation to funding patterns and campaign representation (e.g., Cho & Kim, 2017; Zheng et al., 2014), advocating the need for further studies on crowdfunding and on its potential links to internationalization (Shneor & Maehle, 2020). From this point of view, if, on the one hand, little research has investigated crowdfunding and internationalization (e.g., Cumming & Johan, 2016, 2019), on the other hand, even fewer studies have specifically focused on the role played by ECF and RCF in the context of SMEs (e.g., Di Pietro et al., 2018).

ECF – which, until few years ago, was not accessible to small business entrepreneurs in search of external financing (Johan & Zhang, 2020) – now represents an alternative fundraising tool and an important source of knowledge for SMEs (Troise and Tani, 2021). At the same time, RCF is an interesting tool for SMEs to get feedback on their products (e.g., Belleflamme et al., 2014; Cholakova & Clarysse, 2015; Mollick, 2014). SMEs leverage the ‘wisdom of the crowd’ (Belleflamme et al., 2014; Polzin et al., 2018) (i.e., the skills and knowledge of investors) to obtain benefits such as improved market knowledge, enhanced promotional capabilities, and connections with key stakeholders (e.g., Di Pietro et al., 2018; Estrin et al., 2018; Wald et al., 2019). Through these tools, companies acquire new knowledge on strategy and markets, co-create products/services, foster their public awareness, and exploit crowd networks. In this regard, Di Pietro, et al. (2018) highlighted how crowd inputs can facilitate international expansion of ventures. In particular, the authors suggested that an open approach to heterogeneous crowds of international investors facilitates international exposure, expands geographical reach, and tests any business proposition on a new target audience.

However, apart from Di Pietro et al. (2018), there is a paucity of studies on this topic, which is thus in need of further investigation. Specifically, further evidence is required on the different ways in which SMEs can use crowdfunding (ECF and RCF) to internationalize, and to identify the limitations that govern this relationship.

To shed some light on this, we have adopted the lenses of the RBV (Barney, 1991, 2001) and KBV (Grant, 1996), which over the years have been important reference theories in management and internationalization studies (e.g., Nason & Wiklund, 2018; Pereira & Bamel, 2021).

Current literature has identified five crowdfunding models: RCF, ECF, donation-based, royalty-based and lending-based (Battisti et al., 2020; Miglietta et al., 2019; Vrontis et al., 2021). Although there are three other crowdfunding models besides RCF and ECF, we decide to focus only on these two specific types. The choice to explore RCF and ECF lies in their nature and in their usefulness for the internationalization of SMEs. As previously introduced, recent studies have shown that ECF represents not only a fundraising tool but also a significant source of knowledge that leverages the ‘wisdom of the crowd’ (Battisti et al., 2021; Belleflamme et al., 2014; Polzin et al., 2018;) and a system useful to increase company access to international networks and obtain key benefits (such as improved international market knowledge, enhanced promotional capabilities, and connections with strategic foreign stakeholders) (Di Pietro et al., 2018; Estrin et al., 2018; Wald et al., 2019). Through ECF, SMEs acquire new knowledge on strategy and markets, foster their public awareness, and exploit crowd networks (Di Pietro et al., 2018; Troise and Tani, 2021). These aspects are significant drivers of internationalization and lead SMEs to use ECF; at the same time, it is important to underline that, through ECF, new investors enter the company, therefore becoming more involved in it and interested in proactively helping it in its growth, development, and internationalization (Troise et al., 2021b).

RCF is the best-known and most commonly used crowdfunding system, which helps companies to “garner funds in support of a specific purpose, which often centers on the development or distribution of a new, unfinished, or unproven product” (Davis et al., 2017, p. 90). RCF platforms help companies to raise funds via online campaigns in exchange for currently available or future products (Belleflamme et al., 2014; Cholakova & Clarysse, 2015; Davis et al., 2017; Mollick, 2014). Through RCF campaigns, companies can offer their products as rewards and also test the so-called ‘pre-order’ of new products (Belleflamme et al., 2014). Cumming and Johan (2016, p. 113) highlighted that “reward-based crowdfunding is known to provide proof of concept to innovators, or proof that the service or product offered has a demand and the funds raised are used to meet this demand”.

The features described above show that both ECF and RCF have a high potential and represent ideal systems for SMEs that intend to internationalize. Conversely, the nature of other crowdfunding models makes them less suited to this goal. For example, donation-based crowdfunding is mainly suited to non-profit goals, while the lending-based model is comparable to a bank loan – with backers acting as lenders and receiving a predefined interest rate within a certain period of time – hence, it has different logics compared to RCF/ECF and the role of the crowd is different from that of providing further benefits for companies. Instead, royalty-based crowdfunding is still in its infancy and the number of these specific platforms is still extremely limited.

Table 1 summarizes the key concepts discussed in this section.

Table 1.

Key concepts discussed

| Concepts | Summary |

|---|---|

| Importance of SMEs for countries | Economic development; impact on GDP; employment growth; competitiveness; innovativeness; prosperity |

| Drivers and motivation to internationalize | Strategic behavior; geographic diversification; performance improvement; experiences of foreign partners; customer followership; niche markets; ‘global mindset’ |

| Challenges/barriers to internationalization | Religious, language and ethnic barriers; limited financial resources; incomplete foreign market information and contacts; lack of knowledge |

| Options to gain resources | Venture Capitalists; Business Angels; Crowdfunding |

| Crowdfunding as strategic option | Alternative to traditional fundraising systems; online calls through Internet-based platforms reducing geographical constraints; quickly reach a large crowd of investors; financial and non-financial resources; knowledge and skills of the crowd; sources of knowledge by leveraging the ‘wisdom of the crowd’; crowd involvement in the businesses in which they invest; network effects; digital platforms intermediation; enabling openness to crowd; increased publicity and company/product awareness; enhanced promotional capabilities; connections with key/strategic stakeholders; improved knowledge on product/service, strategy and market; access to international networks; network and knowledge exploitation; test the ‘pre-order’ of new products; proof of concept; proof of demand existence; product feedback |

Methodology

Research Design

Our research design was based on a multiple case study aimed at investigating the ways SMEs use ECF and RCF to internationalize, and the related limitations (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007; Yin, 2009, 2017). As our study explored a recent phenomenon and was aimed at achieving a deep understanding of it, a qualitative research was particularly suitable because it enables the inductive building of theory and, at the same time, a multiple-case study approach enhances the external validation of the findings (on the one hand, it enables a possible replication strategy and, on the other hand, it favors new analysis) (Eisenhardt, 1989; Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007; Gioia & Pitre, 1990). Moreover, such an approach is useful as it provides empirical descriptions of a new phenomenon. Estrin et al., (2018, p. 429) underlined that crowdfunding – and ECF in particular – is a “relatively recent phenomenon … which has novelty and where related scholarly literature is sparse”, and there hence is the need to leverage a study that is “qualitative and inductive in design”. In our case, both RCF and ECF are new phenomena – as SMEs have only recently begun to exploit these systems to internationalize – and their connection with internationalization is still an unexplored field (Cumming & Johan, 2016; Shneor & Maehle, 2020).

In line with prior research in the emerging field of crowdfunding (e.g., Di Pietro et al., 2018; Estrin et al., 2018) and in order to enhance our study’s qualitative rigor (Gioia et al., 2013), we undertook our empirical research following the so-called ‘Gioia methodology’.

Research Setting

Our study investigated a sample of Italian SMEs that had used ECF and RCF to internationalize. We chose to focus on companies that resorted to these systems in order to conduct an in-depth exploration (Cholakova & Clarysse, 2015) and to shed new light on this research field. We specifically opted for Italian SMEs as our research context for several reasons.

First, a large part of the Italian business structure is characterized by SMEs. According to the classification of the European Commission, these ventures have the following characteristics: no more than 250 employees and an annual turnover not in excess of 50 million euros or an annual balance sheet total not exceeding 43 million euros. These companies – which make up most of Italy’s production base and are the main targets (as previously anticipated) of both the ECF and RCF systems – play a key role in the economy of the country. In fact, SMEs employ 82% of Italy’s workforce (a share greater than the European average), represent 92% of the country’s active companies, and contribute significantly to the national GDP.1

Second, given the importance of SMEs for the Italian economy, the Italian government pays particular attention to their internationalization and it strives to support this scope through ad hoc actions. Recently, in fact, it has introduced specific measures to foster the internationalization of SMEs (e.g. Decreto Crescita or, recently, the Law n. 58 – 2019). The goal of supporting business growth was also set in the promulgation of the crowdfunding regulation. In relation to crowdfunding, Italy is a developed country; in fact, it had been the first European country to introduce a specific regulation for ECF – namely, the Decreto Legge n. 179/2012 or “Decreto Crescita Bis” (Battisti et al., 2020; Troise et al., 2020b, 2021b; Vrontis et al., 2021). Moreover, the ‘CONSOB’ (Commissione Nazionale per le Società e la Borsa) Italian authority introduced a registry for ECF operators (Rossi et al., 2019; Rossi & Vismara, 2018; Troise and Tani, 2021). Both ECF and RCF platforms have spread rapidly in the country and are frequently used by SMEs (Politecnico of Milan, 2020), thus representing valuable opportunities for these ventures to raise funds and additional resources.

Third, over the years, scholars highlighted that the internationalization of Italian SMEs represents an interesting research area and they tried to explore how these specific companies pursue internationalization (Colapinto et al., 2015; D’Angelo et al., 2013; Festa et al., 2020). Until recently, the cross-national boundaries of these companies were still mainly focused on their home regions (D’Angelo et al., 2013) and, traditionally, their unique and consolidated presence on the worldwide market lay in the so-called “Made in Italy” products (Festa et al., 2020). Italian SMEs have some typical features (e.g., family-oriented approach to several activities such as the networking and the management of human resources) (D’Angelo et al., 2013), however they are showing a great propensity to digitalization and proactively adopt new digital technologies (Cassetta et al., 2020), including crowdfunding platforms (Troise et al., 2021a; Troise and Tani, 2021). Hence, the study of the internationalization of Italian SMEs by leveraging the potential of crowdfunding represents an important research opportunity.

Finally, following some prior studies (e.g., D’Angelo et al., 2013) our focus on Italian SMEs is a potential response to appeal of Barney et al. (2011) for more research on companies smaller and different from Multinational Enterprises, by adopting the RBV lens.

Sample and Data Collection

Our research was focused on SMEs that had successfully used ECF and RCF – i.e., those that had operated successful campaigns on these platforms, collecting (or exceeding) their funding goals. Our sample of such companies was selected through purposeful approach (Patton, 2014). We had a good knowledge of the companies that had resorted to crowdfunding platforms because two authors had previously developed some studies on the topic (especially on ECF) and had already carried out surveys or interviews with some CEOs as well as examined various crowdfunding campaigns. This enabled us to establish direct connections with several of these ventures. At the same time, we knew several SMEs that had provided information on their internationalization goals within their crowdfunding campaigns, disclosed strategies or future outcomes in this regard, and had highlighted some initial post-campaign results in terms of their internationalization. An additional step in this phase was to further check our sample SMEs’ crowdfunding campaigns to gain knowledge on their internationalization goals – i.e., the companies’ future strategies and use of the funds thus raised – and their websites to get information on their post-campaign performance.

Our two actual examples of ECF campaigns were as follows. A company that produced hi-tech products – with particular attention to environmental issues – had launched a campaign with the goal to internationalize through a network of commercial agents, speed up its international marketing (by means of a high percentage of the funds it had raised), and invest in machinery and R&D. A company that had developed a (patented) easy-to-install technology capable of increasing energy efficiency had run a campaign with the aim of raising the funds needed to finalize the development of a complete marketable module (to be installed in buildings) for the global market, to expand its team with highly skilled and knowledgeable members (investors), to start the pre-industrialization of the production process, and to develop the related marketing/commercial activities needed to offer the product globally. As for the latter company, it was interesting to note that it had carried out two successful ECF campaigns.

Our two actual examples of RCF campaigns were as follows. An SME that had launched a new product based on an innovative technology had run a campaign with the aim of testing it and starting to sell a small number of units (at a low initial price) on the international market, while, at the same time, improving it through customer feedback. A relatively young and small company that had launched a campaign to raise the funds needed to fully complete the development of its product – an online service (based on both websites and mobile apps) – and to be able to offer its final version within the following year. Both these companies had offered their product/service as a reward and had described their goals in their campaigns’ pages.

We first conducted pilot interviews with five CEOs whose SMEs had used the crowdfunding systems under study: three ECF and two RCF. These interviews were useful to ensure the clarity of the questions by making any changes needed to improve it. As mentioned above, two of the authors had a strong relationship with and were close to SMEs that had used ECF and RCF; this enabled us to carry out interviews more easily, facilitating the data collection. Another aspect worth pointing out is that some of the interviewees had facilitated our connection with a number of SMEs pertinent to our study, thus providing new sampling opportunities. This logic is better known as the ‘snowball sampling’ method, which “relies on referrals from initially sampled respondents to other persons believed to have the characteristic of interest” (Johnson, 2014, p.1). In our case, some interviewees were particularly helpful and sensitive to the topic investigated, which facilitated our connections with other CEOs or – in some cases – CFOs, who, in turn, provided us with access to the CEOs. Notably, some companies were connected to each other and others shared their CFOs. All these aspects were useful to establish connections with further companies (in particular those funded through RCF).

Over a period of about five months – from May 2020 to September 2020 – we collected data from various sources, as reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Data sources

| Source | Typology |

|---|---|

| Interviews |

In person = 3 Microsoft Teams = 16 Google Meet = 8 Skype = 7 Phone and VOIP calls = 10 Written = 4 |

| Duration of interviews | On average = 35 min |

| Company social media |

YouTube |

| Websites |

Company official websites Specific blogs SME ecosystem databases and websites |

| Crowdfunding Platforms |

Specific campaign sections (e.g., strategies, use of funds) Post-campaign interviews Company updates |

| Other sources | Dedicated press |

Specifically, we used semi-structured interviews conducted with CEOs as our primary data source, and company websites/social-media and platform dedicated blogs/interviews or campaign pages as our secondary ones, to learn about SME use of ECF/RCF to internationalize and its related limitations. Our secondary sources were relevant as the sampling process we adopted involved the search for cases rich in illustrative information, which, in our specific case, revolved around internationalization. Hence, the additional step to triangulate our data was particularly useful. Through company websites and social media, we were able to collect data on company campaign updates and post-campaign scenarios and developments in relation to internationalization. Some of our sample companies disclosed key information on both their investors/backers and their followers – e.g., new international agreements or partnerships and the launch of new products/services in foreign countries. In some cases, company websites were found to be rich in information about company development, while social media was found to be a valuable channel to update information and photos.2 Some companies posted information on both their websites and social media about the development of new and highly innovative products/services for the international market and on the channels used to distribute them (including the e-commerce ones) or the main countries served.

At the same time, we looked at crowdfunding platforms and, notably, we found interesting updates posted by SMEs. Although the campaigns had ended, the companies were posting information for their investors/backers on dedicated pages in order to provide the crowd with useful details on the post-campaign scenarios, which represented a valuable source of information. Recently, some platforms had started to include specific spaces on these aspects and to require companies to provide periodic updates to investors. An example of this was the ‘CrowdFundMe’ ECF platform, which, in its (closed) campaigns pages, was found to include a specific index – the ‘Completeness index of the KPIs’ – which made it possible to verify, on a quarterly basis, the degree of diligence of the issuer in updating shareholders on business trends.

We conducted 48 semi-structured interviews. Specifically, 25 with CEOs of SMEs that had used ECF and 23 with those of SMEs that had used RCF. Semi-structured interviews conducted with CEOs (i.e., highly knowledgeable informants) provided us with the flexibility to investigate the new topics (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007; Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009), and thus represented the best sources of primary data for our research. Due to the constraints imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, we were only able to conduct three interviews face-to-face, while all the others – apart from four in writing – were conducted through specific platforms (i.e., Microsoft Teams, Skype, and Google Meet) or by means of phone or VOIP calls (including WhatsApp ones). To ensure that they would provide spontaneous answers, our respondent CEOs had not been informed of any specific questions prior to the interviews (Easton, 2010). They were allowed to speak freely about the topics of our research – i.e., the ways in which their companies had used ECF or RCF to internationalize as well as the main related limitations. As an additional step, we probed the interviewees in order to elicit their more in-depth insights into the most relevant aspects and, where possible, to get them to provide practical examples.

All the interviews were conducted by two researchers, so that one of the two could take notes and observe the approach (or any lack of understanding or focus) of each respondent CEO. In a few cases, the interviews were recorded (through the related platform function) and then transcribed. The two researchers involved then carefully transcribed each interview, applying any useful handwritten field notes. The interview protocol – which was standardized – involved open-ended questions. We asked the informants to illustrate the ways in which their SMEs had used ECF or RCF to internationalize, the main motivation for/benefits of bypassing traditional channels/systems, and the limitations they had faced and/or believed to be related to these internationalization systems.

As a last data collection step, we relied on several other useful sources. Most of the crowdfunding platforms were found to disclose valuable information on the post-offering scenarios, such as updates and specific interviews with CEOs describing the benefits of ECF/RCF and what the companies had done once the campaigns had ended or how they had used the funds. These specific data were found to be particularly useful as they provided insights into how some companies had started their internationalization process and how they had leveraged their investors’ international commercial networks (in the case of ECF) or offered products abroad (in the case of RCF). Most of the internationalization strategies adopted were also found to have been disclosed by the SMEs within their crowdfunding campaigns. Some companies, in fact, had explicitly stated that they would use any funds collected to internationalize – i.e., to create international commercial networks, implement export strategies, develop production in foreign countries, or establish international agreements. At the same time, the companies’ websites and their main social networks/media – such as Facebook and LinkedIn – provided interesting information on their international development and growth. Finally, specific press releases and dedicated blogs completed the SMEs’ post-campaign information.

Once the data collection was complete, we obtained a final sample of 48 SMEs that had used a variety of crowdfunding platforms.3 The characteristics of our sample SMEs and of their CEOs are described in Table 3. As our primary source of information on our sample SMEs, we consulted the official Business Register and, through it, we were able to check their respective industry sectors, the years of their establishment, the cities in which they were headquartered, and information related to their CEOs. In regard to this last aspect, we also checked the CEO profiles posted as part of the crowdfunding campaigns, their curricula and their personal web or social media profiles – e.g., on LinkedIn, Facebook, etc. (hypertext links to both the CEOs’ personal websites or social media were found to be almost always included in the campaigns). Most of our sample companies were located in northern Italy, were under 10 years of age, and belonged to the service sector (e.g., information and communication services) or to the industry, manufacturing, or crafts ones.4 In relation to the characteristics of our sample CEOs, they mostly held a level of education above the bachelor’s degree (some of them held a Ph.D. or a master’s degree) and they were quite heterogeneous in terms of age and years of experience (they were distributed quite evenly in this regard). The characteristics of both companies and CEOs were in line with those described in recent dedicated reports (see, among others, Politecnico of Milan, 2020). Therefore, our sample was found to reflect the trends and average characteristics of the population of companies that had used crowdfunding.

Table 3.

Sample characteristics: SMEs and CEOs details

| Company characteristics | Location | North | 67% |

| Center | 21% | ||

| South and Main Islands | 12% | ||

| Company age | < 5 | 56% | |

| 5–10 | 38% | ||

| > 10 | 6% | ||

| Sector | Services | 58% | |

| Industry, crafts, and manufacturing | 25% | ||

| Others | 17% | ||

| CEO characteristics | CEO industry experience | ≤ 5 years | 52% |

| > 5 years | 48% | ||

| CEO age | ≤ 40 | 44% | |

| > 40 | 56% | ||

| CEO education | Bachelor's degree or lower | 35% | |

| Master’s degree or higher | 65% |

Data Analysis

As mentioned above, we used the ‘Gioia methodology’ to examine the qualitative data. We did so because this specific methodology represents a “systematic approach to new concept development and grounded theory articulation that is designed to bring ‘qualitative rigor’ to the conduct and presentation of inductive research” (Gioia et al., 2013, p.15). This qualitative rigor helped us to overcome the wide (and often sparse) range of data, a typical issue of qualitative studies.

First, two researchers carefully reviewed the primary data obtained from the semi-structured interviews in order to identify any common concepts derived from the main themes and to disclose any new insights related to the connections between crowdfunding (ECF or RCF) and internationalization (Punch, 2005). In this first analytical step, we also leveraged our field notes and other data in order to both support and refine our interpretation of any emerging concepts. The other three researchers took a neutral ‘outsider perspective’ – i.e., “the higher-level perspective necessary for informed theorizing” (Gioia et al., 2013, p. 19). As argued by Gioia et al., (2013, p. 19) “the fact that we try to stay so close to the informants’ experience has its downsides. A major one is the risk of ‘going native’, namely, being too close and essentially adopting the informant’s view, thus losing the higher-level perspective necessary for informed theorizing”. Hence, the contributions of these three researchers were highly relevant in overcoming this potential issue and to provide focus in relation to the main emerging concepts. After a discussion between the five researchers – that included the three ‘outsider/neutral’ researchers’ views – the set of codes, and hence the first-order concepts, were defined (Charmaz, 2006; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Then, following the grounded theory approach, we aggregated these first-order concepts into three main second-order themes developed through the analysis of the emerging patterns and relationships (Gioia et al., 2010, 2013). Once we had achieved ‘theoretical saturation’ (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Morse, 1997) and internal validity through different empirical data sources, we combined the second-order themes in two aggregates, one for each crowdfunding model examined – a choice in line with Estrin et al. (2018) – and we discussed the findings accordingly.

The process of analysis and the empirical findings are illustrated below. Two data structures are presented in Figs. 1 and 2. Each figure contains three second-order themes that collapse in aggregate dimensions. Figure 1 is related to ECF and contains 21 first-order concepts, while Fig. 2 is related to RCF and contains 23.5

Fig. 1.

Equity crowdfunding – data structure

Fig. 2.

Reward crowdfunding – data structure

Findings

In the following sub-sections, we discuss the ways in which SMEs use ECF and RCF to internationalize and their related limitations. Our final data structures (Fig. 1 for ECF and Fig. 2 for RCF) summarize the interrelations of our first-order concepts, second-order themes, and aggregate dimensions (Gioia et al., 2013). The first sub-section – Equity crowdfunding and internationalization (4.1) – reports the findings from the interviews conducted with the CEOs of the 25 SMEs that had resorted to ECF, while the second sub-section – Reward crowdfunding and internationalization (4.2) – outlines the results of those conducted with the CEOs of the 23 SMEs that had resorted to RCF.

For both crowdfunding models, the empirical analysis of the aggregate dimensions – i.e., the ways in which the SMEs had used ECF/RCF to internationalize and their limitations – are supported by three second-order themes: the ways to use ECF/RCF to internationalize; bypassing traditional channels and fundraising systems; and the limitations linked to the use of ECF/RCF to internationalize. In line with other studies (e.g., Estrin et al., 2018), we discussed two of the three second order themes – specifically, the ways in which ECF or RCF can be used to internationalize bypassing traditional systems/channels – together within the related findings, which are discussed in the order proposed in Figs. 1 and 2. In addition to the second-order themes, the first-order concepts are also discussed in order of representation (see Figs. 1 and 2).

Equity Crowdfunding and Internationalization

How to Use ECF to Internationalize Bypassing Traditional Channels/Fundraising Systems

Most of the interviewed CEOs pointed out that ECF is an effective and alternative system to raise the funds needed to internationalize that, at the same time, represents a new way to increase the visibility of SMEs and expand their international commercial networks. The primary goal of the SMEs that resort to ECF is to obtain financial resources. In their campaigns, these companies pitch their strategies – including their internationalization ones – and the ways they intend to use any funds raised. Many SMEs specifically highlight their plans to internationalize (in business plans attached to their campaign posts or in dedicated sections such as ‘Strategies’ or ‘How we will invest the capital raised’) and detail each step they intend to take in order to achieve such goal thanks to the financial resources collected. In addition to the business plans (e.g., economic and financial information or projections) and the company value information (e.g., pre-money valuation and equity offered), the other key elements of an ECF campaign that can act as observable and credible signals to induce investors to commit financial resources are: videos, images, updates, comments, company team details, and descriptions of both product and strategies. In regard to these aspects, one of our sample CEOs said that a video – which had been circulated both on the campaign post and on several social media – had caught the attention of a foreign company, which had then contacted them to establish collaborative relationships. Another sample CEO reported that the comments and updates posted during the campaign had signaled the constant presence and attention of the company towards its actual and potential investors. This highlighted the importance of communication and (voluntary) strategic disclosure for companies in the ECF context.

Several CEOs stated that the funds had been used to expand their businesses in strategic foreign markets and to create or develop specific commercial networks. In relation to this aspect, a CEO argued that, through ECF, “we have developed a commercial network that we would not have been able to do with our own resources alone”, while another one said “thanks to ECF, we have created a commercial network and have explored new foreign markets such as that of large retailers”.

As highlighted by many CEOs, the use of ECF represents a significant way for SMEs to gain visibility and to establish contacts with foreign market players. In fact, two CEOs shared interesting experiences in this regard. The first one reported that,

“Our company increased its visibility by participating in the equity crowdfunding mechanism; the crowdfunding campaign allowed us to show our products, innovations and future strategies which attracted many domestic investors but – at the same time – also the attention of foreign companies. The latter found the initiative interesting and aligned with their vision and mission, therefore they contacted us and expressed interest in cooperate with us for the expansion of our business in their country as well as for a future merger or acquisition”.

While the second one said that,

“Even if the equity crowdfunding platform we used is an Italian one, its reputation gave us an international visibility. In fact, our campaign was noticed by foreign companies, in particular two large Chinese and Arabs companies that showed interest in our activities and products”.

This second quote shows that the reputation of the platforms also plays a key role in providing endorsement for SMEs. The interviews also revealed that both the ECF platforms and the campaigns increase a business’s credibility and reputation at both the domestic and international levels, and, at the same time, act as an advertising channel for it. In particular, a CEO argued that “Without the campaign, we would not have received the same publicity and we would not have got in touch with some foreign companies that are still in contact with us”. In this vein, a number of CEOs suggested that ECF had increased their SMEs’ international awareness and promotion through platforms as an alternative channel that is currently both widespread and popular.

Many of the interviewed CEOs cited accessing international networks of investors as one of the main ways to internationalize their companies. Investors in ECF campaigns effectively purchase a company’s shares therefore become directly involved in it. They contribute to the company’s growth and internationalization as they have a vested interest in its positive performance and financial returns. A CEO declared that “One of the crowd investors has contacts with important foreign actors and has shared his international network. Thanks to him, we were able to win contracts both in Dubai and Singapore”. Similarly, a CEO highlighted that “Our new shareholders played a key role in enhancing our company’s international networks and in providing new contacts of distributors and supply chains. We were able to develop international agreements thanks to the contacts provided by the crowd investors and to the funds raised during the campaign”. Another CEO focused on the importance of investor expertise, saying “One of our crowd investors has extensive international experience and skills useful to accelerate the internationalization of our business”. In addition to their expertise, investor knowledge is also an important asset, as suggested by some CEOs. The importance of new (crowd) investors in supporting the internationalization of a company was also confirmed by a CEO whose firm had launched two ECF campaigns and had thus gained valuable knowledge and contacts (as well as consolidated networks) from some investors who possessed extensive knowledge of the international market and showed great commitment to and interest in the initiative.

Some of the campaigns had received funds from thousands of investors, and “many new investors provide more knowledge than a few”. It is critical for SMEs to leverage the knowledge (or wisdom) of the crowd to internationalize their business, as the new investors have “specific knowledge of foreign markets and valuable information suited to expand the business in several foreign countries as well as to improve the export strategies of firms”. A CEO highlighted that the “investors pressured the company to launch a new product on an international reward-based platform through a campaign to test it and get initial feedback”. This proved to be an important suggestion – based on investor knowledge and experience – that enabled the firm to make its product known abroad and to get more financial resources (the campaign raised about 90,000.00 euros).

International expansions strategies are crucial for SMEs; accordingly, a number of CEOs disclosed that, in this regard, the crowd had provided important added value and new opportunities to be seized. A CEO pointed out that even those ECF campaigns that do not have internationalization as their primary goal are an important way to “trigger the process and to internationalize not alone but with a defined logic, thanks to people who know more than we do”.

Two other intriguing aspects that emerged from the interviews were related to the marketing and intellectual property spheres. The first pertained to the creation of an international brand in order to increase a company’s competitiveness and enhance the effects of its marketing activities. On this aspect, a CEO reported that “thanks to the funding raised at the end of the campaign and to the feedback from our investors, as well as their interactions with partners, we decided to develop a specific international brand and registered it”. The second was related to international intellectual property rights protection, and to patents in particular. Three CEOs highlighted that their SMEs had decided to extend their patent protection internationally (i.e., extend the registration of their patents at the international level through the Patent Cooperation Treaty) thanks to the international visibility achieved during the campaign, which had boosted their internationalization as a result of the interest of foreign players and of the suggestions made by new shareholders. In this case, the ECF mechanism had provided the funds needed to register the patents internationally – which is particularly expensive (in addition to the registration taxes, some onerous maintenance fees must also be considered) – and had highlighted the need for SMEs to protect their intellectual property rights in order to compete at the international level and not risk losing the benefits accrued through an invention abroad.

Limitations of the Use of ECF to Internationalize

The interviews also revealed some limitations in the use of ECF to internationalize. The main issues underlined by our sample CEOs were linked to limitations for foreign investors. In fact, due to legal constraints, these investors had faced difficulties in investing in SMEs in Italy through ECF: any foreign entity wishing to invest in an Italian company needed to have an Italian tax code in order to enable the Italian Chamber of Commerce to register it as a new shareholder on the Business Register. This had represented a major obstacle to the internationalization of Italian SMEs. However, the Italian Economic Development Ministry (Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico – MISE) removed this obligation at the end of 2020. In this regard, a CEO pointed out that “until now, only domestic investors [or foreign ones with an Italian tax code] could invest in our company through an ECF campaign”, and that “apart from the tax code, another problem for foreign investors is linked to banks asking for specific requirements and acting as intermediaries for financial flows or transactions”.

Some CEOs reported that, in general, the ECF system, unlike the RCF one, does not allow companies to offer products or services (companies can only offer equity shares). A CEO reported that “we would have liked to offer our products and services to foreign investors through the ECF campaign”. An interesting aspect was revealed by a CEO, who underlined that,

“Our business aims both at increasing its capital and at distributing our products; however, with ECF, it is currently only possible to sell equity shares and not products […]. In our case, this represents a limitation, and we need to think of other systems to sell or distribute our products abroad. A possible future option, in this regard, could be the use of reward crowdfunding”.

However, even if only recently, some ECF platforms have begun to allow the offering of some rewards to new shareholders. Despite this new development, the ability to offer products or services was still reserved to domestic investors in the company. It is important to underline that the interviews were conducted before the MISE’s intervention; therefore, these limitations may be removed in the future.

Two further limitations that emerged from the interviews were related to the restrictions affecting domestic platforms and to the absence of e-commerce policies or dynamics. Some CEOs argued that the lack of dedicated policies represented a limitation to their companies’ internationalization and development. Among them, one claimed that “currently, the absence of e-commerce policies in the ECF represents a limitation for small and medium companies. In this sense, companies remain excluded from the potential of e-commerce and therefore from its strategic potential for their development and internationalization”. At the same time, all our sample SMEs had used domestic ECF platforms, which lacked considerable international impact and, with few exceptions, were completely unknown to foreign investors. For example, a CEO argued that,

“We were contacted by two foreign companies interested in our business; however, as they both told us, these contacts had occurred because they were engaged in activities very similar to ours and were looking for innovative technological solutions […]. Without this kind of affinity, it would have been difficult for them to become aware of our company and our campaign”.

Reward Crowdfunding and Internationalization

How to Use RCF to Internationalize Bypassing Traditional Channels/Fundraising Systems

Unlike ECF, RCF is a valuable tool that enables SMEs to test their products and/or services on crowds around the world. Unlike ECF platforms, which only enable SMEs to sell equity shares, RCF ones make it possible for them to offer their products/services as rewards; thus, RCF campaigns are mainly focused on describing the characteristics of the products/services on offer. Given the virtual nature of crowdfunding platforms and of the campaigns posted on them, companies divulge specific information on the quality of their products to increase crowd knowledge, especially abroad. Companies mitigate their information asymmetries in regard to third-parties by providing detailed descriptions, constant updates, user comments, specific high-quality images, and real-life videos. Other valuable, and less expensive, quality signals that can be sent to international backers involve information on shipping methods and delivery times.

The backers provide small amounts of financial resources in exchange for current or future products/services. All the interviewees highlighted that RCF represents a new channel for companies to both validate their products and receive feedback useful to customize their products to the needs and tastes of specific foreign countries. A CEO argued that,

“We used an international platform, i.e., Kickstarter, and through the reward crowdfunding campaign, several backers provided interesting inputs and feedback. Some backers have tested our product [which was offered as a reward] and we have received positive feedback on its current status, and confirmation that the product could be bought on the market by acquaintances in their sphere. Instead, another backer specifically told us that our product [an electronic product] needed some modifications in order to be functional and usable in his country; he also suggested solutions to make this possible”.

The RCF system enables SMEs to test their products or services without excessive effort and with very low costs. This represents a significant advantage of this tool, as evidenced by several CEOs. For example, a CEO said “We launched a campaign without too many ambitions, not to gain great financial resources, but to get an idea of the opinion of consumers from other foreign countries.” Another said,

“In my opinion, the reward crowdfunding was a win-win mechanism: for us, we received both money and market validation; our consumers had a new and unproven product that would only be launched about six months later with a roughly 40% higher price”.

In these cases, several CEOs suggested that the pre-order mechanism had favored the participation of many foreign consumers and enabled managing orders to satisfy the backers.

Some CEOs highlighted RCF as an alternative way for SMEs to offer their products/services internationally at a lower cost than those involved in traditional systems and, moreover, to overcome any cross-border transactions costs. A CEO underlined that,

“Reward crowdfunding is an attractive option to sell our products not only domestically but also to buyers abroad […]. Based on our experience, I would recommend it to other companies that intend to have a first approach at the international level or that plan to internationalize in the mid-term”.

Another CEO pointed out that,

“We expressly chose to exploit reward crowdfunding for its economic convenience; we decided to offer 900 units of our product through the campaign and, although the price proposed during the campaign was lower than that of the future market launch, the final fee to be paid to the platform was acceptable and affordable. Put simply, it was cheaper compared to the other channels we had in mind”.

Some CEOs declared that RCF was useful for SMEs to compete on a global scale. This system enables companies to offer their products to foreign backers thanks to the platform’s capability to attract international backers and to the lower costs involved. SMEs can leverage the power of the RCF mechanism and of the word-of-mouth effect generated. Another interesting aspect to consider is the unique mechanism featured by RCF whereby backers can test and validate a product. This represents an added value compared to similar tools. Moreover, backers can pre-order a product at a price lower than that of its future market launch. In this regard, companies can thus implement specific price discrimination strategies.

While ECF was found to be affected by several restrictions linked to the specific regulations of each country, the RCF system involved an ‘open door’ mechanism for companies all over the world. The governments of many countries have enacted an open-door policy for global companies that resort to RCF. At the same time, e-commerce regulations reduce distances and favor the purchases of products and services by consumers through RCF campaigns, wherever the SME is located in relation to its backers. In this vein, a CEO argued that “RCF helped our company to reduce the geographical distance with our backers; without this system, this would have been more difficult”.