Abstract

Ubiquitin and its relatives are major players in many biological pathways, and a variety of experimental tools based on biological chemistry or protein engineering is available for their manipulation. One popular approach is the use of linear fusions between the modifier and a protein of interest. Such artificial constructs can facilitate the understanding of the role of ubiquitin in biological processes and can be exploited to control protein stability, interactions and degradation. Here we summarize the basic design considerations and discuss the advantages as well as limitations associated with their use. Finally, we will refer to several published case studies highlighting the principles of how they provide insight into pathways ranging from membrane protein trafficking to the control of epigenetic modifications.

Abbreviations: βgal, β-galactosidase; CAF-1, chromatin assembly factor 1; C-, carboxy-; DD, destabilising domain; DHFR, dihydrofolate reductase; DSB, double-strand break; DUB, deubiquitylation enzyme; E3, ubiquitin protein ligase; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FA, Fanconi Anaemia; FKBP, FK506-binding protein; FRB, FKBP-rapamycin-binding domain; GFP, green fluorescent protein; GG, di-glycine; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HP1γ, Heterochromatin protein 1γ; MVB, multivesicular body; N-, amino-; NEMO, NF-kappa-B essential modulator; NF-κB, nuclear factor 'kappa-light-chain-enhancer' of activated B-cells; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance; PIP, PCNA-interacting peptide; rapa, rapamycin; S. cerevisiae, Saccharomyces cerevisiae; SIM, SUMO interaction motif; SNARE, SNAP receptor; SUMO, small ubiquitin-like modifier; SURF, split ubiquitin for the rescue of protein function; TAD, transcriptional activation domain; TShld, traceless shielding; TLS, translesion synthesis; Ub, ubiquitin; UBD, ubiquitin-binding domain; UFD, ubiquitin fusion degradation; VCP, valosin-containing protein. Amino acids are designated by their one-letter code

Keywords: Ubiquitin, SUMO, Protein engineering, Protein stability, UFD, Degron technology, Endocytosis, Mitophagy, Genome maintenance, Transcriptional regulation

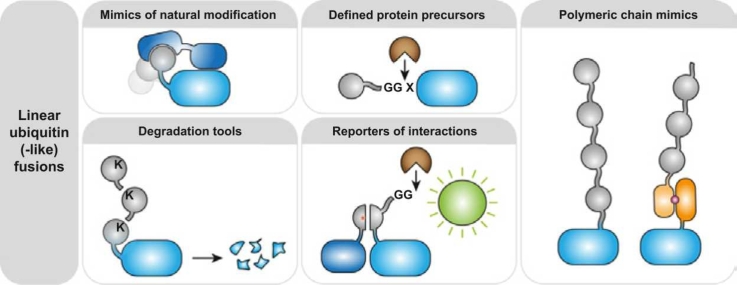

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Flexible tethering facilitates the use of ubiquitin-like proteins in linear fusions.

-

•

Linear fusions are widely used to study the functions of ubiquitin-like modifiers.

-

•

Linear ubiquitin fusions can be used to control protein stability and degradation.

1. Introduction

Posttranslational protein modifications are essential regulatory devices that contribute to signal transduction by modulating protein function, interactions and localization. As they do not require de novo protein synthesis, they are well suited for rapid adaptations to changes in the cellular environment. Among the many posttranslational modifiers, the small protein ubiquitin is one of the most versatile because it can adopt a variety of structures when conjugated to its target proteins [1], [2], [3]. Conjugation is mediated by a complex ensemble of enzymes (‘writers’) and usually involves a linkage between the carboxy (C)-terminal glycine of ubiquitin and the ɛ-amino group of a lysine (K) residue within the target protein. Conjugation to a protein’s amino (N)-terminus or to serine, threonine or cysteine residues has also been reported [4], [5]. When attached as a single unit, known as monoubiquitylation, ubiquitin plays a role in diverse processes such as endocytosis and intracellular vesicle transport, chromatin structure, DNA repair and autophagy [6], [7]. However, key to ubiquitin’s versatility as a signalling molecule is its ability to form polymeric chains via one of its seven lysine residues or its N-terminus. Depending on the linkage of these chains, polyubiquitylation can target proteins for degradation by the 26 S proteasome or activate a variety of alternative pathways [8], [9]. The biological effects of ubiquitylation are mediated by effector proteins (‘readers’) that recognize the conjugates via dedicated ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) [10]. Finally, a set of deubiquitylation (DUB) enzymes (‘erasers’) contributes to ubiquitin regulation by removing the modification from its target proteins or modulating polyubiquitin chain length [11], [12]. Together, this intricate system of writers, readers and erasers constitutes the ‘ubiquitin code’ [2], [3]. Related modifiers of the ubiquitin family follow a similar principle of signalling, although their ability to form chains appears less critical for their function [1].

A plethora of experimental tools is available to investigate the members of the ubiquitin family and their functions, ranging from mass spectrometry-based techniques and in vitro ubiquitylation assays to linkage-selective DUBs, UBDs and affinity probes [8], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. In this review, we will describe an alternative approach based on engineered, linear fusions of the modifier, designed to mimic posttranslational modification by ubiquitin or its relatives. Such fusions have been used to directly address the functional consequences of the modification for the target but have also served as reporter constructs to monitor protein interactions, stability or DUB activity. Here we will discuss relevant design principles, advantages and limitations of the strategy and survey cases illustrating how this approach can provide valuable mechanistic information about the signalling function of the modifier in proteolytic and non-degradative contexts or be exploited to control protein homeostasis in vivo. We will mainly focus on ubiquitin itself but highlight other members of the ubiquitin family where similar principles apply.

2. The ubiquitin fusion strategy

2.1. Advantages and limitations

Functional studies of posttranslational protein modifications are often limited by the low abundance of the modified form of a protein of interest. Permanent fusion of a ubiquitin-like modifier in place of the physiological modification overcomes this problem, thus greatly facilitating the investigation of biophysical properties, protein-protein interactions or enzymatic activities and avoiding the need to generate enzymatically modified proteins in vitro. This is particularly helpful in cases where the modification sites or the cognate conjugation factors are unknown. Permanent fusions also allow the consequences of the modification to be examined in isolation from the physiological signal responsible for inducing the modification, thus eliminating interference from other aspects of the respective biological pathway. Moreover, stable fusions allow a greater control over the exact structure of the modification, for example by using variants of the modifier unable to form chains or engage in specific interactions. Finally, the exquisite selectivity of the cognate proteases can be exploited for controlled cleavage and release of fusion constructs in vivo or in vitro. This approach has been extensively used in tools controlling protein stability (see Section 4).

Several drawbacks must be weighed against these advantages. First and foremost, a linear fusion will be structurally different from a substrate modified at the native attachment site and will thus always be considered artificial. Any result obtained with such construct should therefore be verified in a physiological setting. Beyond the notion that some proteins do not tolerate modifications of their N- or C-termini, a non-native attachment site may not always provide functionality or accessibility to relevant interaction partners. The fusion constructs might also compete with the endogenous form of the protein, thus interfering with its function by dominant-negative effects. Moreover, permanent fusions will fail if deconjugation of the modifier is important for functionality. Finally, employing fusions to investigate the signalling functions of a modifier is a risky strategy in the sense that experiments yielding negative results are inconclusive as the failure of a fusion partner to complement the lack of the native modification could result from problems unrelated to the biological function.

2.2. General design considerations

Strategies involving ubiquitin or ubiquitin-like fusion constructs involve engineered linear arrangements of the modifier and a fusion partner, for example a modification target, in a head-to-tail fashion. Polyubiquitin or poly-SUMO chains can be mimicked by linear arrays of several moieties, either directly adjacent or separated via a peptide linker. Several important features need to be considered when designing fusions to avoid problems related to the non-physiological nature of these artificial constructs.

2.2.1. Non-physiological attachment site of the modifier

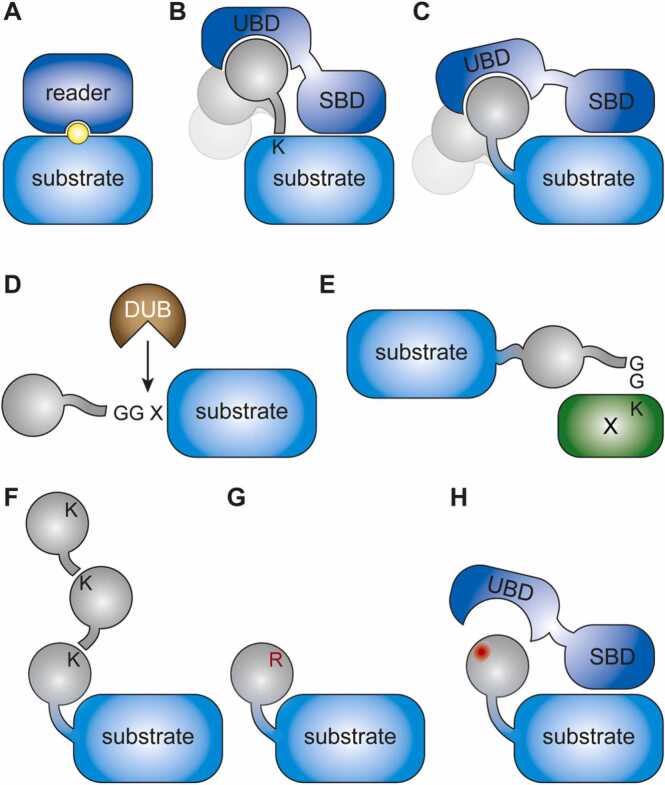

Small posttranslational modifications, such as phosphorylation, methylation and acetylation, are usually recognized by effector domains in the context of the modified substrate protein itself (Fig. 1A). Prominent examples of such composite recognition sites are histone modifications, where both the type of modification and its precise position are important for the functional outcome [18], [19]. In contrast, conjugates of ubiquitin, SUMO and other ubiquitin-like modifiers are generally bound by their readers via a combination of separate substrate- and modifier-binding domains [8], [10], [13] (Fig. 1B). Moreover, the extended unstructured C-terminus of all the members of the ubiquitin family allows for significant flexibility in the positioning of the modifier on the substrate. For example, molecular simulation and X-ray scattering experiments have demonstrated high conformational flexibility of ubiquitylated and sumoylated PCNA [20] and interaction of ubiquitylated PCNA with its reader protein, Polymerase η, involves significant rotation of the ubiquitin moiety (see Section 6.1.1. below). X-ray crystallography and NMR studies of SUMO conjugated to UBC9 and PARP-1, respectively, support the model of a flexible tethering between the modifier and its target [21], [22]. Fusion of the modifier to the N- or C-terminus of a protein as a mimic of a natural, branched conjugate exploits this principle by assuming that the conformational flexibility will allow recognition by a natural effector protein (Fig. 1C). Additional flexibility may be incorporated by means of a peptide spacer between the modifier and the substrate. At the N-terminus of ubiquitin, a spacer may help to increase the distance between the C-terminus of the substrate and the folded modifier domain. For SUMO, a linker is likely less important in this arrangement because of its extended N-terminus. If placed behind the C-terminus of the modifier, glycine residues – often used to provide maximal flexibility – might pre-dispose the linker to cleavage by DUBs. However, a systematic study of the effects of linkers is lacking, and their importance may largely depend on the conformation and exposure of the respective terminus of the fusion partner.

Fig. 1.

Design of ubiquitin fusion constructs. (A) Small posttranslational modifiers (yellow) are often recognized in conjunction with the substrate. (B) Ubiquitin and related modifiers (grey) are generally recognized by separate modifier-binding (UBD) and substrate-binding (SBD) domains. (C) Recognition of linear fusions is facilitated by the flexible tethering via ubiquitin’s C-terminus. (D) N-terminal ubiquitin fusions with native C-termini are substrates of endogenous DUBs. (E) C-terminal ubiquitin fusions with native C-termini are subject to conjugation to cellular proteins. (F) Fusions to wild-type ubiquitin can engage in polyubiquitin chain formation. (G) K-to-R mutations prevent chain formation. (H) Mutation of ubiquitin’s hydrophobic patch (red) can prevent recognition by UBDs. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2.2.2. C-terminal di-glycine motif of the modifier

The C-terminal di-glycine (GG) motif of ubiquitin or related modifiers should be deleted or mutated to a bulky amino acid such as valine or leucine at position 76 in both C- and N-terminal fusions for expression in eukaryotic cells. Failure to do so in N-terminal fusions will result in removal of the fusion protein by cellular DUBs (Fig. 1D) and – depending on the expression level of the construct – an increase in the overall cellular concentration of the modifier itself, with potentially unwanted consequences. However, cleavability can also be exploited to generate proteins with a defined N-terminus differing from the native methionine [23], [24]. C-terminal fusions may be subject to charging by the endogenous conjugation machinery and thus attached to other cellular proteins with unpredictable consequences [25] (Fig. 1E). For instance, Qin et al. [26] demonstrated that expression of a PCNA-Ub fusion inhibits cell proliferation and causes a checkpoint response. This effect was fully dependent on the C-terminal GG motif of ubiquitin but independent of ubiquitin’s lysine residues and therefore likely a result of unspecific attachment of the fusion to cellular proteins rather than linear chain assembly as proposed by the authors. In other situations, conjugation of the fusion protein may be desired, for example when using N-terminal fusions of GFP to tag ubiquitin for visualization purposes [25] or in the context of the yeast two-hybrid system, where fusions of SUMO to the Gal4 DNA-binding domain either containing or lacking the C-terminal GG motif were used as baits to differentiate between covalent and non-covalent SUMO interactors [27].

2.2.3. Properties of the fused modifier

Further enzymatic modification of a fused monoubiquitin moiety can provide insight into the pathway triggered by the polyubiquitylation of the protein of interest (Fig. 1F). Hence, abolishing chain formation by mutation of relevant lysine residues on the ubiquitin moiety allows for a differentiation between effects induced by mono- versus polyubiquitylation (Fig. 1G). Additionally, mutation of residues involved in the interaction of the modifier with its readers, such as the hydrophobic patch of ubiquitin around isoleucine 44 [28], may shed light on the type of UBD involved in its recognition (Fig. 1H). Finally, it is important to rule out non-specific effects, such as steric hindrance by the fused modifier, by showing that they cannot be recapitulated by fusion of an unrelated protein to the target of interest. Such phenomenon was reported for a histone variant, H2AX [29], where an N-terminal fusion of ubiquitin bypassed the requirement of RNF8 for the formation of radiation-induced 53BP1 foci. The notion that the same effect was observed for SUMO1, SUMO2 and even GFP suggested that the functional consequences were unrelated to ubiquitin but mediated merely by the bulky N-terminal extension.

2.2.4. Avoiding endogenous modification of the target

When assessing the consequences of an engineered fusion of a modifier to a protein of interest, it is necessary to simultaneously abolish the endogenous modification of that protein either by mutating known acceptor sites or by depleting or inactivating the cognate cellular conjugation factors. This will prevent interference from physiological modification signals and allow the observation of any downstream consequences in isolation.

3. Split ubiquitin as a reporter for protein-protein interactions

A special manifestation of ubiquitin fusion technology is the split-ubiquitin system [30]. It builds on the notion that many proteins, when divided into two disconnected fragments, can still adopt a near-native structure by non-covalent interactions. When ubiquitin is split after amino acid 34, neither of the two halves in isolation is recognized or cleaved by DUBs or triggers a ubiquitin-like physiological response (Fig. 2A). A single point mutation in the N-terminal half (I13A) lowers the basal affinity of the two parts for each other, thus avoiding spontaneous re-assembly. This feature is exploited by the classical split-ubiquitin interaction assay, where the two halves are fused at the separation sites to two proteins of interest. In addition, a reporter protein is fused to ubiquitin’s C-terminus. Interaction between the two proteins of interest brings the ubiquitin halves into proximity, leading to their refolding into a native-like structure, recognition and cleavage by an endogenous DUB and release of the reporter protein [30], [31], [32] (Fig. 2B). Several reporters have been developed to detect protein-protein interactions in split-ubiquitin assays for yeast and mammalian cells [30], [33], [34], including assays designed for membrane proteins, which are poorly amenable to other reporter-based systems such as the yeast two-hybrid assay [35].

Fig. 2.

The split-ubiquitin system. (A) Ubiquitin can be separated into two self-associating domains at G35. (B) Protein-protein interactions are detected by DUB-mediated release of a reporter upon re-assembly of the ubiquitin structure (red: I13A mutation). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Ubiquitin fusions as tools to study and manipulate protein stability

4.1. The N-end rule pathway

Ubiquitin genes naturally encode linear fusions to ribosomal proteins that are rapidly processed upon translation [36]. This notion formed the basis of a series of seminal experiments by Varshavsky and co-workers in the 1980 s leading to the discovery of the first major ubiquitin-dependent degradation system, the ‘N-end rule pathway’ [23], [37] (Fig. 3A). Fusing a cleavable N-terminal ubiquitin moiety to a model protein, β-galactosidase (βgal), allowed them to replace the N-terminal methionine by any of the other 19 amino acids in budding yeast. They found that the half-life of the resulting protein depended on the identity of the exposed N-terminal residue. While some amino acids afforded metabolically stable proteins, others destabilized the model proteins significantly [23]. Degradation of these unstable proteins was found to be initiated via formation of a K48-linked polyubiquitin chain by the ubiquitin protein ligase (E3), Ubr1, also called N-recognin, at a lysine situated in spatial proximity to the N-terminus [37], [38], [39]. Similar degradation patterns were observed for other model proteins such as X-DHFR, provided that a suitable acceptor site was available nearby [37].

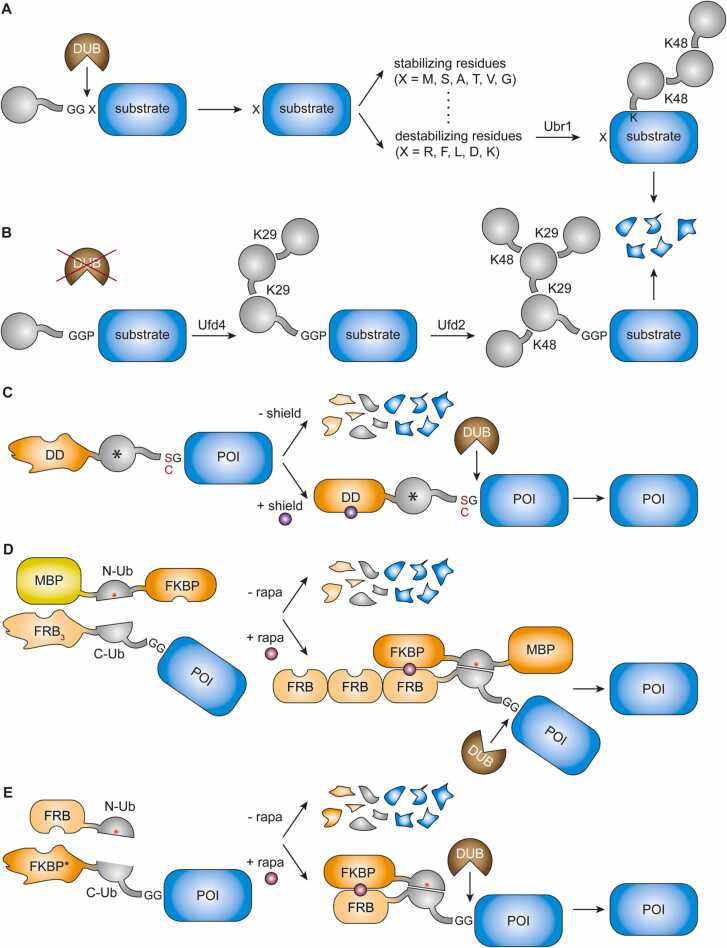

Fig. 3.

Ubiquitin fusions in proteasome-mediated degradation. (A) The N-end rule pathway. (B) The UFD pathway. (C) The LIBRON system. * : Ub(K0). (D) The SURF system. MPB: maltose-binding protein; rapa: rapamycin. (E) The TShld system. FKBP* : F36V, L106P.

4.2. The UFD pathway

In the series of Ub-βgal or -DHFR fusions above, exchange of methionine for proline proved an exception as the construct was rapidly degraded without involving a cleavage of the N-terminal ubiquitin moiety [23]. The short half-live was independent of lysine residues in βgal or DHFR, but dependent on selective lysines within the ubiquitin moiety itself [40]. Thus, an N-terminal ubiquitin fused to a protein of interest was found to serve as an autonomous, cis-acting degradation signal, or degron (Fig. 3B).

The pathway responsible for degrading non-cleavable ubiquitin fusion proteins has been dubbed the ubiquitin fusion degradation (UFD) pathway [40]. Genetic analysis revealed a set of five genes, termed UFD1 to UFD5, as contributing to degradation, among them the genes encoding the cognate E3, Ufd4, and a chain elongation factor, or E4, Ufd2 [40], [41]. Mutational analysis of the N-terminal ubiquitin moiety also revealed that two lysine residues, K29 and K48, were important for ubiquitylation and degradation. While the need for K48 varied with the substrate, K29 was found to be critical for all substrates tested. Accordingly, further biochemical analysis revealed that Ufd4 assembles a short K29-linked ubiquitin chain on the N-terminal ubiquitin moiety, which is subsequently branched by K48-linkages, catalyzed by Ufd2, and the resulting structure is required for efficient degradation [41], [42]. Intriguingly, placement of the ubiquitin moiety at the C-terminus of a model substrate did not trigger efficient ubiquitylation or degradation, irrespective of the presence or absence of the GG motif, whereas placement in between two domains afforded ubiquitylation and degradation via the UFD pathway [25]. Although few physiological substrates have been identified yet, the E3s of the N-end rule pathway and the UFD pathway work partially together and can enhance the efficiency of degradation [43].

4.3. Fluorescent ubiquitin reporter constructs

Based on the original N-end rule and UFD substrates, N-terminal fusions of ubiquitin to fluorescent proteins have been widely used to study and quantify proteasome-mediated protein degradation in cells and whole organisms (reviewed in [44], [45], [46], [47]). In one approach, N-end rule-based fluorescent protein sensors are designed for cleavage by DUBs and release of the fluorescent protein whose half-life is determined by its exposed N-terminal residue [23]. Thus, the introduction of destabilizing amino acids such as arginine or leucine allows monitoring of changes of ubiquitin proteasome-mediated protein turnover [48]. Alternatively, UFD-based fluorescent protein sensors are designed as non-cleavable ubiquitin fusions by mutation of G76 of ubiquitin to valine, subject to ubiquitylation and degradation by the UFD pathway [48].

N-end rule- and UFD-based fluorescent protein sensors highlight advantages and limitations of ubiquitin fusion proteins. On the one hand, recognition and cleavage of ubiquitin by endogenous DUBs in combination with the N-end rule is an elegant approach to release a fusion protein with a controlled half-life in cells. On the other hand, expression of a stable N-terminal ubiquitin fusion with a DUB-resistant mutant of ubiquitin such as Ub(G76V) can trigger proteasomal degradation via chain extension, but potentially also unwanted monoubiquitin-dependent signalling events by the fused ubiquitin moiety itself.

4.4. Degron technology

4.4.1. N-end rule-based degrons

Understanding the N-end rule has allowed the design of a tool not only for manipulating the half-life of a protein of interest, but also for its inducible degradation. This so-called degron technology is based on the temperature-dependent, differential exposure of a destabilizing N-terminal amino acid (arginine) of a temperature-sensitive, thermally labile mutant of dihydrofolate reductase, DHFR [49]. The mutant R-DHFR is fused N-terminally to a protein of interest and further extended by a cleavable N-terminal monoubiquitin unit. The latter is constitutively cleaved by endogenous DUBs, but the resulting destabilizing N-terminus remains cryptic at low temperature and only becomes exposed at the non-permissive temperature of 37 °C, thus inducing ubiquitylation and degradation of the fusion protein.

4.4.2. Ubiquitin variant fusions as tools to control protein stability

The principle of exploiting DUB cleavage in combination with an unfolded domain to induce degradation has been further refined by the recent development of a ‘liberation-prone degron’, or LIBRON [50] (Fig. 3C). Here, a lysine-less ubiquitin variant is used as cleavage tag between a destabilising domain (DD) and the protein of interest. The DD is stably maintained by a small cell-permeable ligand, which results in cleavage of the DD-ubiquitin moiety and release of the stable, untagged protein of interest. In the absence of the ligand, however, the DD unfolds and causes rapid degradation of the entire fusion construct by the proteasome. The big advantage of this approach is its applicability to proteins whose N-termini cannot be modified without loss of function, and several DDs have been created and characterized by Wandless and colleagues [51], [52], [53], [54].

4.4.3. Split ubiquitin as a tool to control protein stability

In a similar manner to LIBRON, the split-ubiquitin system has been employed to control protein stability and fusion protein release in an inducible manner. The SURF (split ubiquitin for the rescue of protein function, Fig. 3D) and TShld technologies (traceless shielding, Fig. 3E) build on destabilizing mutants of the dimerizing domains of FRB or FKBP12, respectively, which are stabilized via heterodimerization in the presence of rapamycin [55], [56]. These DDs are fused to the N-termini of the two halves of split ubiquitin, and the protein of interest is appended to the C-terminus of the half-ubiquitin moiety. Hence, addition of rapamycin induces the re-folding of ubiquitin and the DUB-mediated release of the protein of interest from ubiquitin’s C-terminus, while in the absence of rapamycin the latter is degraded along with the DD.

4.5. SUMO fusion technology

Contrary to the degron approach, SUMO can serve as a protein stabilizer. This feature of SUMO, based on empirical observations, is sometimes exploited in recombinant protein production, where an N-terminal SUMO fusion often boost the expression and solubility of the partner protein [57]. As a bonus, controlled cleavage of the SUMO moiety by SUMO-specific protease as part of the purification process allows for a production of recombinant proteins with a free N-terminus.

5. Ubiquitin fusions as tools to study membrane protein trafficking

5.1. Endocytosis

An important proteolytic system alternative to the 26 S proteasome is the lysosome or vacuole [58], [59]. Internalization of membrane proteins and transport to the lysosome via the multivesicular body (MVB) pathway depend on multiple ubiquitylation events [60], [61] and ubiquitin fusion proteins have been instrumental in elucidating the mechanistic basis of protein trafficking in this pathway.

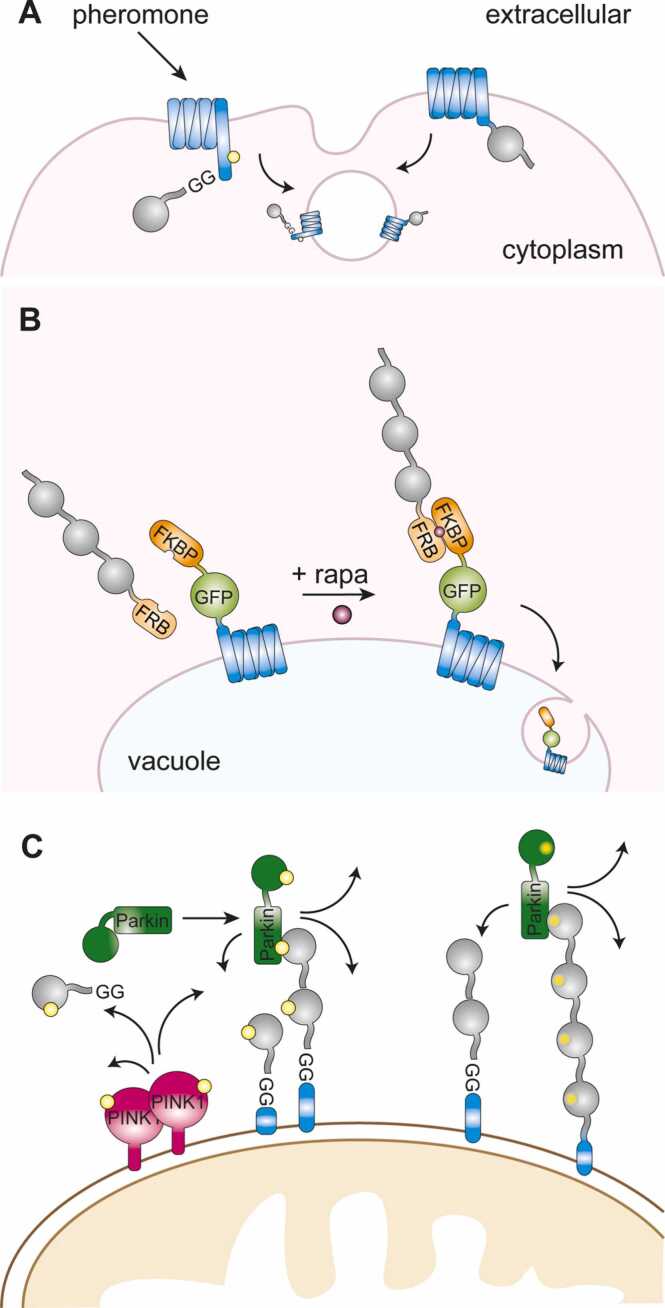

5.1.1. Ubiquitin fusions to cargo proteins

Modification of plasma membrane proteins by ubiquitin had been recognized to initiate their endocytosis [62]. Definitive evidence that a single ubiquitin moiety is sufficient for rapid internalization and vacuolar degradation was provided by fusing ubiquitin to the C-terminus of a G-protein coupled receptor, Ste2, in budding yeast [63]. Truncation of the receptor to remove its physiological signalling properties and mutation of the lysine residues within the ubiquitin moiety revealed that phosphorylation of the receptor or polyubiquitin chain formation were dispensable for internalization [64] (Fig. 4A). Moreover, activation of endocytosis of a normally stable protein, the plasma membrane ATPase, Pma1, by fusion of a C-terminal ubiquitin moiety demonstrated that ubiquitin itself can act as an internalization signal [64].

Fig. 4.

Ubiquitin fusions in membrane protein trafficking. (A) Internalization of a membrane receptor by endogenous signal-induced ubiquitylation (left) or via permanent fusion of ubiquitin (right). (B) Vacuolar targeting via RapiDeg. (C) Ubiquitylation of outer mitochondrial membrane proteins via PINK1 activation and phosphorylation (yellow) of ubiquitin and Parkin (left) or in the absence of PINK1 by a linear phosphomimetic tetraubiquitin fusion as a receptor for phosphomimetic Parkin (right).

The E3 responsible for the modification of plasma membrane proteins in yeast was identified as Rsp5, the yeast homolog of human NEDD4 [65], [66]. However, Rsp5 was found to modify not only cargo proteins, but also several components of the endocytic machinery [67]. Moreover, Rsp5 promotes the conjugation of short, K63-linked polyubiquitin chains that significantly enhance the efficiency of endocytosis [68]. Teasing apart the relevant ubiquitylation substrates and conjugate structures has again been facilitated by ubiquitin fusion constructs. Stringer et al. [69] fused DUB enzymes to multiple components of the endocytic machinery to prevent ubiquitin-dependent protein sorting along the MVB pathway. Cleavage-resistant fusion of ubiquitin to some cargo proteins such as Mup1, Fur4 or Ste3 restored entry into the MVB pathway, indicating that Rsp5-dependent ubiquitylation of non-cargo components was not required. Interestingly, this approach did not extend to all cargo proteins, indicating important differences between the various cargoes with respect to their requirement for internalization. Use of a genetic background in which K63 of endogenous ubiquitin is mutated to arginine demonstrated the importance of K63-polyubiquitylation for endocytosis; yet the notion that a Mup1-GFP-Ub(K63R) fusion was sorted to the vacuole indicated that K63-chains – although important – did not necessarily have to reside on the cargo itself [69].

Ubiquitylation is important not only for internalization of plasma membrane proteins, but also as a sorting signal late in the endocytic pathway [70]. A study involving a special type of polyubiquitin mimic demonstrated ubiquitin-dependent cargo sorting directly at the vacuolar membrane. In an approach dubbed RapiDeg, Emr and coworkers targeted a linear head-to-tail fusion of three ubiquitin moieties to a vacuolar amino acid transporter, Ypq1, via a rapamycin-inducible dimerization system [71]. This non-covalent ‘modification’ induced vacuolar uptake and degradation, demonstrating that linear polyubiquitin chains can mediate delivery to the vacuole when associated with the cargo (Fig. 4B).

Ubiquitin-mediated membrane protein sorting is highly conserved between yeast and mammalian cells. Accordingly, ubiquitin fusion constructs have also served to investigate the endocytic pathway in human cells. A well-studied model cargo is the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), whose ligand-induced activation causes internalization via endocytosis, followed by either recycling to the plasma membrane or degradation in lysosomes [72], [73]. Fusion of a ubiquitin to EGFR is sufficient to trigger internalization in the absence of the ligand, EGF, or the cognate E3, Cbl [74], [75], [76]. A polyubiquitin mimic, comprising a head-to-tail fusion of four ubiquitin moieties fused to the C-terminal domain of full-length EGFR, bypassed the need for ligand stimulation and kinase activation and triggered constitutive internalization via a clathrin-dependent pathway [76].

The strategy of overcoming DUB-mediated inhibition of ubiquitylation by means of cleavage-resistant fusion of ubiquitin to selected cargo proteins described above has also been applied in mammalian cells. During proliferation of retroviruses, the viral envelope protein, Gag, utilizes the endocytic machinery to afford membrane fission during virus budding [77]. Cleavage-resistant fusion of ubiquitin to the HIV-1 Gag protein restored virus release in a background where physiological ubiquitylation was inhibited by DUB fusions, thus demonstrating the critical role of the modification of the viral protein [78].

5.1.2. Ubiquitin fusions to mediators of membrane trafficking

Efficient endocytosis involves the ubiquitylation of additional factors beyond the cargo proteins. One of these is EEA1, a component of the endosomal fusion machinery. EEA1 is monoubiquitylated at several sites in an E3-independent manner [79]. Permanent fusion to a ubiquitin moiety caused a constitutively activated protein that triggered uncontrolled endosome fusion, resulting in giant endosomes and a defect in the recycling of a plasma membrane receptor.

Ubiquitin fusion constructs were even applied in a transgenic mouse model, where non-cleavable ubiquitin was fused to two SNARE proteins, Synaptobrevin-2 and Syntaxin-1, which mediate the fusion of synaptic vesicles. Although intended as UFD-like reporters of proteasomal degradation, ubiquitin-tagged Synaptobrevin-2 (but not Syntaxin-1) turned out to progressively impair synaptic transmission at the neuromuscular junctions due to a reduction in the endocytosis of synaptic vesicles and membrane trafficking [80]. This striking dominant effect of the fusion construct may have been caused by an abnormal sorting of the SNARE protein and its associated vesicles in the endocytic pathway; however, the mechanistic basis of the phenotype has not been elucidated.

5.2. Mitophagy

Ubiquitin controls membrane trafficking and cargo sorting not only in the context of the endocytic pathway, but also during autophagy, where ubiquitin-binding autophagic receptors select ubiquitylated protein aggregates, organelles or other structures for lysosomal degradation [81]. A special form of autophagy is mitophagy, i.e., the selective elimination of damaged mitochondria as a means of quality control [82]. Depolarization of mitochondria leads to the stabilization of a kinase, PINK1, at the outer membrane, where it activates an E3, Parkin, in a feed-forward process involving phosphorylation of a ubiquitin-like N-terminal domain of Parkin, ubiquitylation of mitochondrial outer membrane proteins as well as phosphorylation of ubiquitin itself [83] (Fig. 4C, left). The ubiquitylated mitochondrial surface is then recognized by autophagic receptors.

Insight into the nature of the receptor responsible for recruitment of phosphorylated Parkin came from a linear, non-cleavable tetraubiquitin construct harbouring phosphomimetic mutations (S65D) and fused to a mitochondrial targeting domain (Fig. 4C, right). In contrast to an analogous wild-type ubiquitin chain, this construct effectively recruited a phosphomimetic Parkin to energized mitochondria in the absence of PINK1 [84]. Importantly, ubiquitin coating of the mitochondrial surface by means of linear, lysine-less di-, tetra- or hexaubiquitin chains fused to the transmembrane domain of an outer mitochondrial membrane protein was sufficient to induce mitophagy independently of PINK1 and Parkin [85]. Intriguingly, a monoubiquitin unit targeted by an FKBP-FRB dimerization system [86] and a linear non-cleavable chain mimic containing wild-type tetraubiquitin that was in principle susceptible to branching by endogenous E3s [87] were ineffective in inducing mitophagy, suggesting that ubiquitin chain branching might interfere with mitophagy. Clearly, the structure of the mitochondrial ubiquitin coat deserves further investigation.

6. Probing nuclear functions with ubiquitin and SUMO fusions

6.1. Regulation of DNA damage bypass

A paradigmatic example of non-degradative ubiquitin function has been the regulation of DNA damage bypass by ubiquitylation of the trimeric replication clamp protein, PCNA. In response to replication stress, PCNA is modified at an invariant lysine residue, K164, by monoubiquitylation and K63-linked polyubiquitylation, which in turn facilitates the replication of damaged templates via two distinct pathways, translesion synthesis (TLS) and template switching. While the details of these pathways have been reviewed elsewhere [88], [89], we will highlight here how fusion constructs have contributed to elucidating ubiquitin signalling functions in this context.

6.1.1. PCNA monoubiquitylation

Monoubiquitylation enhances the affinity of PCNA for a series of damage-tolerant DNA polymerases, thus activating TLS [90], [91] (Fig. 5A). Substituting this modification by fusing ubiquitin to the N- or C-terminus of PCNA enhanced interactions with the TLS Polymerase η in the yeast two-hybrid system in a manner dependent on a UBD in the polymerase, thus demonstrating the modularity of the interaction [92] (Fig. 5B, C). Moreover, expression of the fusion proteins in S. cerevisiae partially substituted for the loss of endogenously monoubiquitylated PCNA, indicating that the precise location of ubiquitin on PCNA is not relevant for functionality. Similar observations were made in mammalian cells, although here an alternative TLS polymerase, REV1, rather than Polymerase η was found to be responsible for the rescue of DNA damage bypass [93]. Later studies in fission and budding yeast largely confirmed the model of TLS polymerase recruitment via independent interaction sites for PCNA and ubiquitin, although some disagreement remained over the question of whether the linear PCNA fusions supported viability in the absence of endogenous PCNA [94], [95].

Fig. 5.

Ubiquitin and SUMO fusions on PCNA. (A) Endogenous monoubiquitylation of PCNA at K164 facilitates recruitment of damage-tolerant TLS polymerases via UBD and PIP motifs. (B, C) Fusions of ubiquitin to the N- or C-terminus of PCNA support recruitment of TLS polymerases when co-expressed with unmodifiable PCNA. (D) Split PCNA facilitates fusion of ubiquitin proximal to its native attachment site, which supports viability and damage bypass in the absence of endogenous PCNA. (E) Endogenous modification of PCNA with Smt3/SUMO1 facilitates recruitment of anti-recombinogenic Srs2/PARI via SIM and PIP motifs. (F) Linear fusions between PCNA and Smt3/SUMO1 support recruitment of Srs2/PARI. (G, H) N-terminal fusion of SUMO2 to PCNA supports recruitment of CAF1 and SSRP1 via SIM and PIP motifs.

An alternative approach to mimic monoubiquitylated PCNA that closely reflects the natural arrangement was devised by Freudenthal and colleagues [96]. Here, PCNA was separated into two parts between residues 163 and 164 and a ubiquitin moiety was fused to the N-terminus of the second, C-terminal fragment. The two PCNA fragments successfully self-assembled, thus reconstituting a mimic of PCNA monoubiquitylated at K164. The constructs formed stable trimers, stimulated Polymerase η in vitro and supported TLS in S. cerevisiae (Fig. 5D). Crystallographic analysis confirmed the native conformation of the PCNA trimer and revealed a significant rotation of the ubiquitin unit when in complex with a C-terminal peptide of Polymerase η compared to its positioning on the surface of PCNA in the absence of the peptide. These structures suggested a high conformational flexibility of ubiquitin on its target protein and an engagement in protein-protein contacts largely dictated by its hydrophobic patch [97].

6.1.2. PCNA polyubiquitylation

The conformation of head-to-tail arrangements closely resembles that of K63-linked polyubiquitin chains [98], suggesting that they might be used to generate mimics of polyubiquitylated PCNA and thus give some insight into how this modification activates template switching. Indeed, interaction of PCNA with the ATPase Mgs1, a putative reader of polyubiquitylated PCNA, was stimulated by a series of non-cleavable linear fusions of 2, 3 or 4 ubiquitin moieties to PCNA, assembled seamlessly or separated by short peptide linkers in the two-hybrid system and in vitro [99]. However, genetic evidence argued against an involvement of yeast Mgs1 in the template switching pathway. Moreover, the constructs failed to support template switching in vivo [100]. Variations of the linker sequence or modification of ubiquitin’s C-terminus to alanine or serine to render the chains partially cleavable did not afford activity either, arguing that the flexibility or cleavability of the junction was unlikely to be important for template switching [101]. These data suggest a yet unidentified reader of polyubiquitylated PCNA capable of discriminating between K63-linked and linear polyubiquitin chains.

Irrespective of their failure to activate template switching, the linear polyubiquitin fusions to PCNA supported TLS when containing linker peptides in between the ubiquitin units, but not when arranged seamlessly [100], [101]. This observation agrees with a model where polyubiquitylated PCNA exerts an inhibitory effect on TLS by sequestering TLS polymerases away from PCNA via the distal ubiquitin units in the chain [102]. However, polyubiquitylated PCNA provides resistance to DNA-damaging agents even in the absence of TLS polymerases, indicating that the inhibition of TLS cannot be the only function of this modification.

Finally, the use of ubiquitin fusions has given insight into the relevance of polyubiquitin chain length in template switching. By means of expressing a fusion of PCNA to a ubiquitin moiety that can be further modified at K63 in a strain background carrying a K63R mutation of its endogenous ubiquitin, the ‘chain’ assembled on PCNA in response to replication stress was limited to a single K63-junction. This arrangement supported substantial template switching activity, highlighting the relevance and functionality of the K63-linkage even in a non-native location [101].

6.1.3. PCNA sumoylation

In budding yeast, PCNA is subject to DNA damage-independent sumoylation during DNA replication. This modification was shown to recruit an anti-recombinogenic helicase, Srs2, to suppress unscheduled homologous recombination at replication forks [103], [104] (Fig. 5E). Hishida et al. [105] demonstrated that an N-terminal fusion of SUMO to PCNA recapitulates the consequences of native PCNA sumoylation and the dependence on Srs2 in genetic assays (Fig. 5F). At the same time, the fusion protein conveyed an increased damage sensitivity in wild type, but not in srs2Δ cells, indicating that constitutive recruitment of Srs2 interferes with correct DNA damage processing.

In contrast to yeast, human cells express three SUMO isoforms, SUMO1–3. Analogous to the situation in budding yeast, a PCNA-SUMO1 fusion strongly inhibits spontaneous and DSB-induced homologous recombination in human cells [106]. Moldovan et al. identified the PCNA-interacting helicase-like protein, PARI, as a putative mammalian analogue of Srs2 by means of its preferential interaction with the PCNA-SUMO1 fusion [107] (Fig. 5F). At the same time, modification of PCNA with SUMO1 was proposed to promote template switching in the context of immunoglobulin diversification in chicken and human B cells, as defects in these reactions – induced by abolishing endogenous PCNA sumoylation – were compensated by expression of a PCNA-SUMO1 chimeric fusion [108].

Modification of PCNA by SUMO2 has been observed in a transcription- and replication-dependent manner and appears to mark the sites of transcription-replication conflicts [109]. Intriguingly, modification with the almost identical SUMO3 was not observed in this study. Two components of histone chaperones, CAF1A and SSRP1, a subunit of the FACT complex, were identified as possible readers of the modification by means of their interaction with a SUMO2-PCNA fusion (Fig. 5G, H). In both cases, interaction was mediated by a combination of a PCNA-interacting peptide (PIP) and a SUMO interaction motif (SIM). Consistent with CAF1’s ability to decrease chromatin accessibility by depositing repressive marks, overexpression of SUMO2-PCNA resulted in reduced chromatin association of RNA polymerase II and in fewer transcription-induced DNA double-strand breaks [109]. Similarly, upon depletion of the factors responsible for SUMO2 modification of PCNA, TRIM28 and RECQ5, expression of the SUMO2-PCNA fusion suppressed the enhanced formation of transcription-induced double-strand breaks [110].

6.1.4. Ubiquitylation of Rad18

Rad18, the E3 responsible for PCNA monoubiquitylation, is itself monoubiquitylated in cells. Its deubiquitylation is important during the mammalian DNA damage response, possibly because of an inhibitory effect of ubiquitylated Rad18 on the activity of the non-ubiquitylated protein via dimerization involving a UBD [111]. Rad18 is ubiquitylated at multiple lysine residues, which has precluded the generation of a ubiquitylation-deficient mutant [112], [113], [114]. Therefore, fusion constructs of Rad18 to ubiquitin have been instrumental in confirming this model. Fusing ubiquitin to the N- or C-terminus of Rad18 promoted its interaction with non-ubiquitylated Rad18 and inhibited its interaction with another E3, SHPRH, responsible for PCNA polyubiquitylation [111]. Mutation of the hydrophobic patch on the ubiquitin moiety abolished the effect, suggesting that ubiquitin and SHPRH compete for binding to Rad18’s UBD and ruling out a mere steric interference of the fusion. Unlike Rad18 itself or the fusion construct bearing the hydrophobic patch mutation, Rad18-Ub does not form foci in response to DNA damage and does not rescue the PCNA ubiquitylation defect and elevated mutation frequency of Rad18-/- cells, thus confirming the dominant negative effect of the ubiquitin moiety on Rad18 functionality.

6.2. The Fanconi Anaemia pathway

Ubiquitin fusions have also contributed to unravelling the role of monoubiquitylation in the Fanconi Anaemia (FA) pathway, involved in the repair of DNA inter-strand crosslinks and bulky DNA adducts. A key event in this genome maintenance pathway is the damage-induced monoubiquitylation of the FANCD2 protein at K563 as a trigger for its localization to chromatin [115]. In the chicken DT40 cell line, a FANCD2(K563R)-Ub fusion – unlike mutant FANCD2 alone – correctly localizes to chromatin and rescues the sensitivity of FANCD2 null cells to crosslinking agents [116]. This rescue depended in part on the hydrophobic patch of ubiquitin, but not on ubiquitin’s lysine residues, indicating that no further ubiquitylation was necessary. At the same time, tethering the non-modifiable FANCD2 mutant directly to chromatin by means of a fusion to histone H2B afforded DNA damage resistance, suggesting that the primary function of FANCD2 monoubiquitylation during the DNA damage response is to target the protein to chromatin.

In mammalian cells, Rad18 has been also implicated in the FA pathway, but the role of PCNA ubiquitylation in this pathway has been debated [117], [118]. Ectopic expression of a PCNA-Ub fusion in Rad18-deficient cells afforded efficient recruitment of FANCD2 to chromatin, suggesting that activation of the FA pathway may occur downstream of PCNA ubiquitylation [119].

6.3. DNA damage-induced signalling pathways

Irreparable DNA damage can lead to cell senescence or apoptosis [120]. Two independent apoptotic pathways are controlled by the transcription factor p53 and by cytokine signalling via ATM and the NF-κB system, respectively [121]. Both pathways involve modification of key players by ubiquitin or SUMO, and linear fusions have been applied to unravel some of their functions.

The pathway regulating the stability of p53 is critical for cell survival upon DNA damage and other stress conditions. It is mediated via mono- and polyubiquitylation of p53 by Mdm2 and other E3s, which drives translocation of the protein to the cytoplasm where it is degraded by the 26 S proteasome. To dissect the role of p53 monoubiquitylation in this process, Li et al. created a linear fusion of ubiquitin to the C-terminus of p53 [122]. Whereas native p53 predominantly localizes to the nucleus, p53-Ub resided in the cytoplasm independently of Mdm2. As a control, fusion of ubiquitin to the C-terminus of an unrelated transcription factor, Max, did not affect its subcellular localization. In contrast, fusion of p53 to SUMO1 only weakly promoted transport to the cytoplasm and fusion to the ubiquitin-like NEDD8 had no effect on p53 localization [123]. The mechanism of how monoubiquitylation destines p53 for export from the nucleus remains to be elucidated, however.

Independently of p53, DNA damage can trigger apoptotic caspase activation via the sensor kinase ATM and the NF-κB pathway, involving a complex crosstalk between modifications of the NF-κB essential modulator, NEMO, by SUMO1 and ubiquitin [124]. Sumoylation of NEMO in the cytoplasm drives its translocation to the nucleus, where it is ubiquitylated in an ATM-dependent manner to promote survival. Accordingly, a linear fusion of SUMO1 to wild-type or sumoylation-deficient NEMO was shown to be sufficient to induce nuclear localization without compromising its functionality in NF-κB signalling [125]. In a later study, it was shown that in cells expressing SUMO1-NEMO, but not NEMO alone, activation of ATM even in the absence of genuine DNA damage caused an activation of the NF-κB pathway, implying that NEMO sumoylation and ATM activation are two separate requirements for activation of the pro-survival pathway in cells experiencing genotoxic stress [126]. Of note, modification of NEMO with SUMO2/3 has also been described, and linear fusion of SUMO3 to the C-terminus of NEMO impaired its interaction with the DUB, CYLD, a negative regulator of NK-κB signalling, without affecting association with IKKβ, a known NEMO interactor [127].

The cytosolic response to genotoxic insult also involves modification of the RIP1 kinase, another signalling factor in the NF-κB pathway, with SUMO and ubiquitin, presumably as K63-linked chains. Yang et al. generated a sumoylation-deficient mutant, RIP1(4KR), and reconstituted RIP1 null cells either with RIP1(4KR) or a SUMO1-RIP1(4KR) fusion. While expression of the kinase mutant had no effect, the SUMO fusion was polyubiquitylated upon doxorubicin treatment and partially rescued NF-κB signalling and the damage sensitivity of the RIP1-deficient cells [128].

Taken together, these examples illustrate how permanent linear fusions can help elucidate the complex interplay between different posttranslational modifiers of the ubiquitin family.

6.4. Regulation of chromatin structure by histone modifications

In the context of the nucleosome, histone tails are abundantly decorated with posttranslational modifications, including methylation, phosphorylation, acetylation, ubiquitylation and sumoylation, thus generating the so called ‘histone code’, responsible for many aspects of chromatin dynamics [18]. Importantly, for the small modifications not only the type, but also the precise position of the modifier within the histone tails is crucial [19].

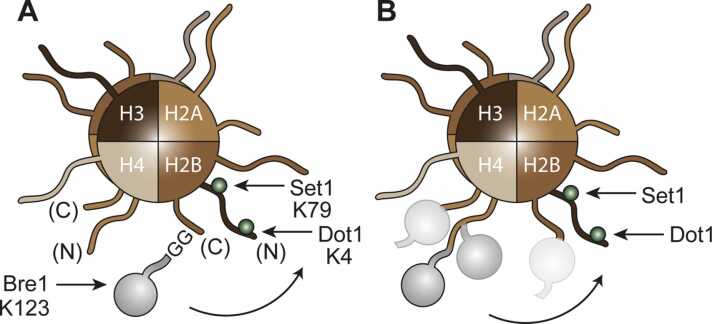

In contrast, the use of linear fusion constructs has revealed a remarkable plasticity with respect to the positioning of ubiquitin on the nucleosome. In S. cerevisiae, histone H2B ubiquitylation at K123 is a prominent modification that triggers ‘trans-histone crosstalk’: ubiquitylation by Bre1 activates methylation of K4 and K79 of histone H3 by Dot1 and the Set1 complex [129], [130] (Fig. 6A). Vlaming et al. [131] generated a series of linear fusions of ubiquitin to various positions at the N- or C-termini of histones H2A or H2B to probe whether these constructs would mediate crosstalk to H3 in a bre1Δ mutant background. They found that many of the non-physiological attachment sites provided at least partial H3 methylation, with an efficiency approximately proportional to the distance of the attachment site to K123 of H2B, but also dependent on the orientation of the ubiquitin moiety relative to the nucleosome structure (Fig. 6B). Polyubiquitylation was irrelevant in this context, as demonstrated using a lysine-less ubiquitin mutant. Importantly, the series of constructs revealed overlapping but also distinct structural features required for activation of Dot1 and Set1, respectively. Moreover, permanent attachment of ubiquitin did not interfere with H3K79-dependent activation of the DNA damage checkpoint, indicating that ongoing ubiquitylation and deubiquitylation are dispensable for functionality. Taken together, these experiments have provided strong support for a flexible tethering of ubiquitin on the surface of the nucleosome, where it is recognized by dedicated readers, and argue against a ‘wedge’ model where the modifier provides access to effectors by disrupting chromatin compaction [132].

Fig. 6.

Trans-histone crosstalk between H2B ubiquitylation and H3 methylation. (A) Bre1-mediated ubiquitylation at H2BK123 stimulates Dot1-/Set1-dependent H3 methylation at K4 and K79 (green). Relevant N- and C-terminal tails are labelled in brackets. (B) Linear fusions of ubiquitin to the N- or C-terminal tails of H2A or H2B stimulate H3 methylation with different efficiencies, depending on distance and orientation of the ubiquitin moiety. For clarity, modifications are shown on only one each of the two histone subunits within the histone octamer. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure, the reader is referred to the web version of this article)

In mammalian cells, regulation of chromatin-associated pathways by histone ubiquitylation is generally well conserved but involves additional writers, such as the BRCA1-BARD1 complex involved in heterochromatin maintenance via H2A monoubiquitylation [133]. While loss of BRCA1 compromises global heterochromatin integrity and induces genome instability and growth arrest, expression of an H2A-Ub fusion restored heterochromatic centres, homologous recombination and proliferation of BRCA1-deficient human cells [134]. As expected, the ability of the fusion to bypass the BRCA1 defects depended on the hydrophobic patch of the ubiquitin moiety. The relevance of H2A monoubiquitylation for homologous recombination received further support from the observation that a H2A-Ub fusion restored proper DSB resection and resistance towards the topoisomerase I inhibitor camptothecin and the PARP-1 inhibitor olaparib in BARD1-depleted cells [135]. A steric hindrance effect was excluded by the notion that fusing an alternative globular protein in place of ubiquitin did not afford any rescue. Again, the position of ubiquitin on the nucleosome was found to be of some importance, as fusion to the N-terminus was much less effective than to the C-terminus, i.e., close to its physiological attachment site.

Linear fusions have also been applied to investigate the consequences of histone sumoylation. Generally, sumoylation in the context of a nucleosome is associated with transcriptional silencing [136]. In S. cerevisiae, ectopic expression of SUMO-H4 or SUMO-H2B fusions caused a dramatic decrease in transcription, estimated by the abundance of GAL1 transcripts upon switching to galactose medium [137]. Importantly, mutation of two SUMO residues that had previously been shown to be important for silencing, K37E and R46E [138], completely abolished the effect, indicating a selective action of the SUMO moiety. In human cells, fusion of either SUMO1 or SUMO3 to the N-terminus of histone H4 enhanced interaction with the histone deacetylase HDAC1 and the heterochromatin protein HP1γ, consistent with a role of histone sumoylation in gene repression [139]. Given the promiscuity of many SUMO interactions and the tendency of SUMO to cover large surfaces or complexes in the manner of ‘molecular glue’ [140], [141], [142], the degree of target selectivity remains to be verified for SUMO modification of chromatin components.

Finally, special consideration should be given to the centromere-specific histone H3 variant, CENP-A, as its ubiquitylation on K124 by a cullin-based E3 complex, CUL4A-RBX1-COPS8, is an absolute requirement for cell viability. Ubiquitylation triggers interaction of CENP-A with the histone chaperone HJURP and leads to CENP-A localization to centromeres. Fusion of monoubiquitin carrying a K48R mutation to the C-terminus of a ubiquitylation-deficient CENP-A mutant, K124R, restored centromeric localization and interaction with HJURP under conditions of CUL4A depletion and viability to the CENP-A(K124R) mutant [143], [144].

6.5. Regulation of transcription factor activity

Modulating chromatin structure via the modification of nucleosomes represents one of several ways in which ubiquitin and SUMO impinge on transcription. An alternative and more selective mode is the direct modification of transcription factors [145].

Many transcription factors are short-lived proteins, subject to ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation. In some cases, the responsible degron overlaps with their transcriptional activation domain (TAD), suggesting an intimate link between activation and degradation [146]. In fact, Tansey and coworkers have suggested that ubiquitylation serves as a ‘licensing’ signal that activates the transcription factor and at the same time marks it for rapid degradation [147]. This model derived from experiments with a heterologous transcriptional activator in budding yeast, a fusion of the viral VP16 TAD to the bacterial LexA repressor. Ubiquitylation of the TAD by an E3, Met30, was found to serve as a dual signal, triggering both transcriptional activation and proteasomal degradation. While fusion of a ubiquitin (G76A) moiety to the N-terminus of LexA-VP16 fully restored transcriptional activation in met30Δ mutants, it did not promote degradation, thus clearly indicating that the activating signal conferred by ubiquitylation can be separated from the degradation signal [147]. Intriguingly, it was later found by Ndoja et al. [148] that activation of LexA-VP16 by fusion to ubiquitin depended on the – albeit inefficient – removal of the ubiquitin moiety, thus implicating deubiquitylation in the activation process. In contrast, fusion of a completely cleavage-resistant ubiquitin mutant, G76V, afforded a stable fusion protein that was transcriptionally inactive due to its extraction from the chromatin by the ubiquitin segregase, Cdc48, the yeast homologue of mammalian VCP/p97. Surprisingly, this did not require polyubiquitylation, as a lysine-less ubiquitin mutant was likewise extracted, but it did involve ubiquitin’s hydrophobic patch. A similar ubiquitin-dependent, but proteolysis-independent inhibitory effect on transcription via Cdc48/p97-dependent promoter clearance was also observed for the endogenous yeast transcription factor Met4 and for receptor-activated R-Smad2/3 complexes in human cells [148]. Of note, monoubiquitylation of Smad4, a co-activator of the R-Smads, was shown to disrupt interaction with Smad2, and a Smad4-Ub fusion construct localized preferentially to the cytoplasm, suggesting a role of ubiquitylation in the turnover of Smad complexes at promoters [149]. Hence, ubiquitylation can have either positive or negative effects on transcription.

In contrast, SUMO has mainly been associated with transcriptional repression. A well-studied example is the transcription factor Sp3, whose sumoylation at K539 within an inhibitory domain close to Sp3’s C-terminus interferes with its activity [150]. Covalent attachment of SUMO1 to the N-terminus of Sp3(K539R) likewise causes a dramatic reduction of its transcriptional activity, indicating that the fusion mimics naturally sumoylated Sp3 despite a drastically different position of the modifier on the Sp3 protein [151]. Similarly, sumoylation of Smad4 at K113 and K159 has been linked to the inhibition of its transcriptional activity. However, Smad4 had been shown to also undergo polyubiquitylation at K113 and K159 [152]. In fact, the negative correlation between Smad4 sumoylation and its stability suggested a possible competition between SUMO and ubiquitin. However, a stable N-terminal fusion of SUMO1 to an otherwise non-modifiable Smad4(K113R/K159R) mutant reproduced the repressive effect of native sumoylation, thus clearly indicating a role of SUMO1 in transcriptional repression not mediated via inhibition of Smad4 degradation [153].

7. Fusions of other ubiquitin-like modifiers

Many of the principles described above for ubiquitin and SUMO also apply to other ubiquitin-like modifiers. For example, heterologous, inducible expression of a NEDD8-specific protease in combination with linear, cleavable NEDD8 fusions to a degron domain has allowed to engineer a system for targeted proteolysis in prokaryotes [154], similar to an analogous approach with ubiquitin that served to study the bacterial N-end rule [155]. Surprisingly, in mammalian cells N-terminal fusions of NEDD8 to GFP cause a ubiquitin-dependent destabilization resembling analogous ubiquitin fusions [156]. Degradation was mediated by the proteasome as well as autophagy, but the responsible targeting mechanism has not been elucidated. Likewise, the inflammation-associated modifier, FAT10, can destabilize GFP and other long-lived proteins as an N-terminal fusion [157]. In fact, FAT10 is thought to directly target proteins to the proteasome in the context of antigen presentation by MHC class I molecules. Accordingly, fusion to a viral antigen induced proteasomal docking and presentation on MHC-I [158]. Antigen presentation via MHC-I is also enhanced by fusion to the anti-viral ISG15; however, this modifier does not induce proteasomal degradation of its fusion partners [159]. On the contrary, ISG15 engages with ubiquitin in mixed chains to inhibit proteasomal degradation, as demonstrated by means of linear ISG15-Ub hybrid constructs [160]. Fusions of ISG15 versus other ubiquitin-like modifiers have also been instrumental in elucidating the selectivity of an ISG15-selective isopeptidase, USP18 [161], and an involvement in the MVB pathway has been postulated based on the localization of an ISG15-GFP fusion [162]. Although certainly incomplete, this catalogue of examples illustrates the widespread use of fusion technology among the members of the ubiquitin family.

8. Conclusions and outlook

Given the artificial nature of permanent modifier fusions, the number of successful case studies in the literature is surprisingly high. While we do not know about the failed experiments, the studies discussed here give cause for optimism regarding the general applicability of the fusion technology for ubiquitin-like proteins. The properties of the modifiers with their C-termini acting as flexible tethers for the respective folded ubiquitin-like domains justify non-native attachment sites wherever the fusion does not interfere with the function of the target protein and within the spatial boundaries set by the size of the target itself. Nevertheless, the permanent nature of the fusion imposes severe limitations to the fusion approach, as discussed above (Section 2.2.). Hence, systems for the inducible enzymatic modification of selected cellular proteins would be highly desirable for a manipulation of posttranslational modifications with higher precision. PROTACs – small molecules designed to induce ubiquitin-mediated degradation via the hijacking of an endogenous E3 – and related techniques relying on the recruitment of engineered E3s are special cases where this approach has been successfully applied [163]. However, they do not account for non-proteasomal functions. An alternative strategy, ProxE3, has employed an engineered E3 to decorate the surface of mitochondria with K63-linked polyubiquitin chains [164]. Site-specific ubiquitylation and sumoylation have been accomplished in mammalian cells by the incorporation of a lysine derivative via genetic code expansion and the use of a sortase-mediated transpeptidation reaction with a ubiquitin or SUMO mutant [165]. However, it remains to be seen how practicable this approach will be in its application. Given the variety of tools already available for the engineering of ubiquitin-related reactions [14], rapid progress toward a full control over substrate- and linkage-selective modifications in vivo is to be anticipated.

Funding sources

The authors’ work was supported by a Research Training Network (UbiCODE, #765445) from the European Commission and a Proof-of-Concept Grant (Ubiquiton, #786330) from the European Research Council to H.D.U.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cappadocia L., Lima C.D. Ubiquitin-like protein conjugation: structures, chemistry, and mechanism. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:889–918. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heride C., Urbe S., Clague M.J. Ubiquitin code assembly and disassembly. Curr. Biol. 2014;24:R215–R220. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwon Y.T., Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin code in the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2017;42:873–886. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciechanover A. N-terminal ubiquitination. Methods Mol. Biol. 2005;301:255–270. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-895-1:255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McClellan A.J., Laugesen S.H., Ellgaard L. Cellular functions and molecular mechanisms of non-lysine ubiquitination. Open Biol. 2019;9 doi: 10.1098/rsob.190147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramanathan H.N., Ye Y. Cellular strategies for making monoubiquitin signals. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2012;47:17–28. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2011.620943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sigismund S., Polo S., Di Fiore P.P. Signaling through monoubiquitination. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2004;286:149–185. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69494-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kliza K., Husnjak K. Resolving the complexity of ubiquitin networks. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020;7:21. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendes M.L., Fougeras M.R., Dittmar G. Analysis of ubiquitin signaling and chain topology cross-talk. J. Proteom. 2020;215 doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2020.103634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Husnjak K., Dikic I. Ubiquitin-binding proteins: decoders of ubiquitin-mediated cellular functions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012;81:291–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051810-094654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clague M.J., Urbe S., Komander D. Breaking the chains: deubiquitylating enzyme specificity begets function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019;20:338–352. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reyes-Turcu F.E., Ventii K.H., Wilkinson K.D. Regulation and cellular roles of ubiquitin-specific deubiquitinating enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:363–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.082307.091526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mattern M., Sutherland J., Kadimisetty K., Barrio R., Rodriguez M.S. Using ubiquitin binders to decipher the ubiquitin code. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2019;44:599–615. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2019.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao B., Tsai Y.C., Jin B., Wang B., Wang Y., Zhou H., Carpenter T., Weissman A.M., Yin J. Protein engineering in the ubiquitin system: tools for discovery and beyond. Pharm. Rev. 2020;72:380–413. doi: 10.1124/pr.118.015651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henneberg L.T., Schulman B.A. Decoding the messaging of the ubiquitin system using chemical and protein probes, Cell. Chem. Biol. 2021;28:889–902. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2021.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mulder M.P.C., Witting K.F., Ovaa H. Cracking the ubiquitin code: the ubiquitin toolbox. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2020;37:1–20. doi: 10.21775/cimb.037.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Tilburg G.B., Elhebieshy A.F., Ovaa H. Synthetic and semi-synthetic strategies to study ubiquitin signaling. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2016;38:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berger S.L. Histone modifications in transcriptional regulation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2002;12:142–148. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Husmann D., Gozani O. Histone lysine methyltransferases in biology and disease. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2019;26:880–889. doi: 10.1038/s41594-019-0298-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powers K.T., Lavering E.D., Washington M.T. Conformational flexibility of ubiquitin-modified and SUMO-modified PCNA shown by full-ensemble hybrid methods. J. Mol. Biol. 2018;430:5294–5303. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knipscheer P., Flotho A., Klug H., Olsen J.V., van Dijk W.J., Fish A., Johnson E.S., Mann M., Sixma T.K., Pichler A. Ubc9 sumoylation regulates SUMO target discrimination. Mol. Cell. 2008;31:371–382. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zilio N., Williamson C.T., Eustermann S., Shah R., West S.C., Neuhaus D., Ulrich H.D. DNA-dependent SUMO modification of PARP-1. DNA Repair. 2013;12:761–773. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bachmair A., Finley D., Varshavsky A. In vivo half-life of a protein is a function of its amino-terminal residue. Science. 1986;234:179–186. doi: 10.1126/science.3018930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunter A.M., Kottachchi D., Lewis J., Duckett C.S., Korneluk R.G., Liston P. A novel ubiquitin fusion system bypasses the mitochondria and generates biologically active Smac/DIABLO. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:7494–7499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200695200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qian S.B., Ott D.E., Schubert U., Bennink J.R., Yewdell J.W. Fusion proteins with COOH-terminal ubiquitin are stable and maintain dual functionality in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:38818–38826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qin Z., Bai Z., Sun Y., Niu X., Xiao W. PCNA-Ub polyubiquitination inhibits cell proliferation and induces cell-cycle checkpoints. Cell Cycle. 2016;15:3390–3401. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2016.1245247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hannich J.T., Lewis A., Kroetz M.B., Li S.J., Heide H., Emili A., Hochstrasser M. Defining the SUMO-modified proteome by multiple approaches in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:4102–4110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413209200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beal R., Deveraux Q., Xia G., Rechsteiner M., Pickart C. Surface hydrophobic residues of multiubiquitin chains essential for proteolytic targeting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:861–866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kocylowski M.K., Rey A.J., Stewart G.S., Halazonetis T.D. Ubiquitin-H2AX fusions render 53BP1 recruitment to DNA damage sites independent of RNF8 or RNF168. Cell Cycle. 2015;14:1748–1758. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1010918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnsson N., Varshavsky A. Split ubiquitin as a sensor of protein interactions in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:10340–10344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller J., Johnsson N. Split-ubiquitin and the split-protein sensors: chessman for the endgame. Chembiochem. 2008;9:2029–2038. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reichel C., Johnsson N. The split-ubiquitin sensor: measuring interactions and conformational alterations of proteins in vivo. Methods Enzym. 2005;399:757–776. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)99050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moreno D., Neller J., Kestler H.A., Kraus J., Dünkler A., Johnsson N. A fluorescent reporter for mapping cellular protein-protein interactions in time and space. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2013;9:647. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petschnigg J., Groisman B., Kotlyar M., Taipale M., Zheng Y., Kurat C.F., Sayad A., Sierra J.R., Mattiazzi Usaj M., Snider J., Nachman A., Krykbaeva I., Tsao M.S., Moffat J., Pawson T., Lindquist S., Jurisica I., Stagljar I. The mammalian-membrane two-hybrid assay (MaMTH) for probing membrane-protein interactions in human cells. Nat. Methods. 2014;11:585–592. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stagljar I., Korostensky C., Johnsson N., te Heesen S. A genetic system based on split-ubiquitin for the analysis of interactions between membrane proteins in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:5187–5192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozkaynak E., Finley D., Solomon M.J., Varshavsky A. The yeast ubiquitin genes: a family of natural gene fusions. EMBO J. 1987;6:1429–1439. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02384.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bachmair A., Varshavsky A. The degradation signal in a short-lived protein. Cell. 1989;56:1019–1032. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90635-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bartel B., Wunning I., Varshavsky A. The recognition component of the N-end rule pathway. EMBO J. 1990;9:3179–3189. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07516.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chau V., Tobias J.W., Bachmair A., Marriott D., Ecker D.J., Gonda D.K., Varshavsky A. A multiubiquitin chain is confined to specific lysine in a targeted short-lived protein. Science. 1989;243:1576–1583. doi: 10.1126/science.2538923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson E.S., Ma P.C., Ota I.M., Varshavsky A. A proteolytic pathway that recognizes ubiquitin as a degradation signal. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:17442–17456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koegl M., Hoppe T., Schlenker S., Ulrich H.D., Mayer T.U., Jentsch S. A novel ubiquitination factor, E4, is involved in multiubiquitin chain assembly. Cell. 1999;96:635–644. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80574-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu C., Liu W., Ye Y., Li W. Ufd2p synthesizes branched ubiquitin chains to promote the degradation of substrates modified with atypical chains. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14274. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hwang C.S., Shemorry A., Auerbach D., Varshavsky A. The N-end rule pathway is mediated by a complex of the RING-type Ubr1 and HECT-type Ufd4 ubiquitin ligases. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12:1177–1185. doi: 10.1038/ncb2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Wijk S.J., Fulda S., Dikic I., Heilemann M. Visualizing ubiquitination in mammalian cells. EMBO Rep. 2019;20 doi: 10.15252/embr.201846520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gierisch M.E., Giovannucci T.A., Dantuma N.P. Reporter-based screens for the ubiquitin/proteasome system. Front. Chem. 2020;8:64. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Menendez-Benito V., Heessen S., Dantuma N.P. Monitoring of ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis with green fluorescent protein substrates. Methods Enzym. 2005;399:490–511. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)99034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matilainen O., Jha S., Holmberg C.I. Fluorescent tools for in vivo studies on the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016;1449:215–222. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3756-1_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dantuma N.P., Lindsten K., Glas R., Jellne M., Masucci M.G. Short-lived green fluorescent proteins for quantifying ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent proteolysis in living cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:538–543. doi: 10.1038/75406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dohmen R.J., Wu P., Varshavsky A. Heat-inducible degron: a method for constructing temperature-sensitive mutants. Science. 1994;263:1273–1276. doi: 10.1126/science.8122109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miyamae Y., Chen L.C., Utsugi Y., Farrants H., Wandless T.J. A method for conditional regulation of protein stability in native or near-native form. Cell Chem. Biol. 2020;27:1573–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2020.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Banaszynski L.A., Chen L.C., Maynard-Smith L.A., Ooi A.G., Wandless T.J. A rapid, reversible, and tunable method to regulate protein function in living cells using synthetic small molecules. Cell. 2006;126:995–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iwamoto M., Bjorklund T., Lundberg C., Kirik D., Wandless T.J. A general chemical method to regulate protein stability in the mammalian central nervous system. Chem. Biol. 2010;17:981–988. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miyazaki Y., Imoto H., Chen L.C., Wandless T.J. Destabilizing domains derived from the human estrogen receptor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:3942–3945. doi: 10.1021/ja209933r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Navarro R., Chen L.C., Rakhit R., Wandless T.J. A novel destabilizing domain based on a small-molecule dependent fluorophore. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016;11:2101–2104. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pratt M.R., Schwartz E.C., Muir T.W. Small-molecule-mediated rescue of protein function by an inducible proteolytic shunt. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:11209–11214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700816104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lau H.D., Yaegashi J., Zaro B.W., Pratt M.R. Precise control of protein concentration in living cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2010;49:8458–8461. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Butt T.R., Edavettal S.C., Hall J.P., Mattern M.R. SUMO fusion technology for difficult-to-express proteins. Protein Expr. Purif. 2005;43:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knop M., Schiffer H.H., Rupp S., Wolf D.H. Vacuolar/lysosomal proteolysis: proteases, substrates, mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1993;5:990–996. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Trivedi P.C., Bartlett J.J., Pulinilkunnil T. Lysosomal biology and function: modern view of cellular debris bin. Cells. 2020;9 doi: 10.3390/cells9051131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Piper R.C., Dikic I., Lukacs G.L. Ubiquitin-dependent sorting in endocytosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014;6 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.MacGurn J.A., Hsu P.C., Emr S.D. Ubiquitin and membrane protein turnover: from cradle to grave. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012;81:231–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060210-093619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hicke L., Riezman H. Ubiquitination of a yeast plasma membrane receptor signals its ligand-stimulated endocytosis. Cell. 1996;84:277–287. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80982-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Terrell J., Shih S., Dunn R., Hicke L. A function for monoubiquitination in the internalization of a G protein-coupled receptor. Mol. Cell. 1998;1:193–202. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shih S.C., Sloper-Mould K.E., Hicke L. Monoubiquitin carries a novel internalization signal that is appended to activated receptors. EMBO J. 2000;19:187–198. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Galan J.M., Moreau V., Andre B., Volland C., Haguenauer-Tsapis R. Ubiquitination mediated by the Npi1p/Rsp5p ubiquitin-protein ligase is required for endocytosis of the yeast uracil permease. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:10946–10952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Springael J.Y., Andre B. Nitrogen-regulated ubiquitination of the Gap1 permease of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1998;9:1253–1263. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.6.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]