Abstract

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Core Factor (CF) is a key evolutionarily conserved transcription initiation factor that helps recruit RNA polymerase I (Pol I) to the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) promoter. Upregulated Pol I transcription has been linked to many cancers, and targeting Pol I is an attractive and emerging anti-cancer strategy. Using yeast as a model system, we characterized how CF binds to the Pol I promoter by electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA). Synthetic DNA competitors along with anti-tumor drugs and nucleic acid stains that act as DNA groove blockers were used to discover the binding preference of yeast CF. Our results show that CF employs a unique binding mechanism where it prefers the GC-rich minor groove within the rDNA promoter. In addition, we show that yeast CF is able to bind to the human rDNA promoter sequence that is divergent in DNA sequence and demonstrate CF sensitivity to the human specific Pol I inhibitor, CX-5461. Finally, we show that the human Core Promoter Element (CPE) can functionally replace the yeast Core Element (CE) in vivo when aligned by conserved DNA structural features rather than DNA sequence. Together, these findings suggest that the yeast CF and the human ortholog Selectivity Factor 1 (SL1) use an evolutionarily conserved, structure-based mechanism to target DNA. Their shared mechanism may offer a new avenue in using yeast to explore current and future Pol I anti-cancer compounds.

Keywords: RNA polymerase I, Core Factor, minor groove, CX-5461, DNA binding, EMSA

1. Introduction

Eukaryotic organisms possess three DNA-dependent RNA polymerases (Pols), Pols I-III, to carry out the essential function of gene transcription [1]. Pol I is responsible for transcribing ribosomal DNA (rDNA) into ribosomal RNA (rRNA), a fundamental step of ribosome biogenesis [2, 3]. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pol I transcribes the rDNA gene into the 35S pre-cursor rRNA that matures into the 18S, 5.8S and 25S rRNAs of the ribosome [3, 4]. Pol I transcription and thus ribosome biogenesis are essential processes as all eukaryotic organisms require ribosomes to facilitate protein synthesis [5, 6]. Consequently, dysregulation of Pol I transcription and subsequent perturbation of ribosome biogenesis plays a role in numerous diseases, including developmental disorders and a wide variety of cancers [7–11].

A critical step of transcription initiation is the formation of the pre-initiation complex (PIC), a protein scaffolding event that occurs at the promoter [12–14]. In S. cerevisiae, two cis-regulatory elements comprise the bipartite rDNA promoter that includes the Upstream Activating Sequence (UAS) and the Core Element (CE) that are each bound by separate Pol I transcription factors [15–17]. Relative to the transcription start site found at the +1 position, the UAS is found approximately between positions −150 to −60 and the CE can be found roughly between positions −40 to +8 [15–17]. The Pol I specific multi-subunit transcription factor complexes that bind the UAS and CE are the Upstream Activating Factor (UAF) and Core Factor (CF), respectively [3, 4, 18]. TATA-box Binding Protein (TBP) is also a component of the Pol I PIC, although its role within the Pol I system is not yet fully understood [19–21]. The final step in PIC formation is recruiting Pol I to the promoter, which is facilitated by the initiation factor Rrn3 that makes contacts with both CF and Pol I [22–26].

Pol I promoters across species are similar in terms of their length and bipartite composition, where they include an Upstream Control Element (UCE) and an Core Promoter Element (CPE) that are analogous to the yeast UAS and CE, respectively [27]. However, there are minor variations in the location and boundaries of these elements within their respective promoters. For example, the human UCE lies approximately from positions −156 to −107, while the CPE resides near positions −47 to +7 [27–29]. In mouse rDNA promoters, the UCE can be found near positions −140 to −111 and CPE near positions −39 to +9 [30, 31], while in the rat rDNA promoter the UCE resides near positions −140 to −60 and the CPE from positions −31 to +6 [32, 33]. To form the human PIC requires interaction of Upstream Binding Factor (UBF) with the UCE through its high-mobility group domains in addition to regions within the CPE and within the rDNA gene locus [34, 35]. In addition, Selectivity Factor 1 (SL1), which includes TBP as a stable complex member, exclusively binds the CPE and is stabilized at the promoter by UBF [36, 37]. Together, UBF and SL1 cooperatively recruit the transcriptionally competent Rrn3 bound Pol I to the rDNA gene promoter [38, 39]. Yeast UAF and human UBF share no apparent sequence homology, whereas yeast CF and human SL1 have been shown to have homology both functionally and structurally [40–42].

CF is a heterotrimer comprised of subunits Rrn6, Rrn7, and Rrn11 and is required for both in vitro and in vivo transcription initiation [43–47]. The recent crystal and cryo-EM structures of CF highlight the bimodular nature of the complex [24, 25, 48]. CF module I includes Rrn11 and the WD40 domain of Rrn6, which makes contact with the upstream end of the Pol I cleft [24, 25, 48]. Module II consists of Rrn7 and the C-terminal headlock domain of Rrn6 and can adopt various orientations during the transcription initiation process due to its intrinsic mobility [24, 48]. A flexible hinge region separates these two modules [24, 25, 48]. Similar to CF, the human SL1 complex is essential for accurate and efficient transcription of rDNA [28]. In addition to TBP, SL1 contains three evolutionarily conserved TBP-associated factors (TAFs), TAF1A (Rrn11), TAF1B (Rrn7) and TAF1C (Rrn6) [40, 49, 50], and two metazoan-specific subunits TAF1D [51] and TAF12 [52]. There are currently no structural data available for the SL1 complex.

Recently, the structure of CF bound to promoter DNA was elucidated using cryo-EM in which CF resembles a right-hand grabbing DNA [48]. In this hand model, Rrn7 forms the fingers, the N-termini of both Rrn6 and Rrn11 form the palm, and the thumb consists of the C-terminus of Rrn11 pointing towards Pol I [48]. These studies revealed that CF associates with the CE of the rDNA promoter using a variety of interactions such as groove and backbone contacts that are mainly mediated by CF subunits Rrn7 and Rrn11 [24, 25, 48]. These structures provide near-atomic detail of the CF-CE interaction and suggest that contacts fall within the −40 to −15 positions as reported by three independent research groups [24, 25, 48]. Although no direct binding assays of SL1 have been published, it is likely that SL1 binds to a region within the human rDNA promoter similar to the yeast CE from positions −43 to −9 as this region has been shown to be important for transcriptional activity as identified by linker scanning mutagenesis [27].

Pol I promoters and the transcription factors that bind to them have a degree of species-specificity [30]. For example, human (h) SL1 and the orthologous mouse (m) factor, TIF-1B, are unable to promote transcription of heterologous DNA templates unless re-engineered [28, 53–55]. The remaining mouse and human Pol I factors, including UBF, hRrn3/mTIF-1A, and Pol I are interchangeable [22, 34, 56, 57]. In the Pols II/III systems, this phenomenon has not been observed in part due to their well-conserved promoter sequences [58, 59]. The observed Pol I species-specificity is the result of concerted evolution [30, 60–62]. Due to the tandem, repetitive nature of the rDNA gene loci coupled with the specialized transcription machinery that bind the promoter sequences, Pol I promoter DNA and its transcription factors evolve at a faster rate and are more divergent than those of other transcription systems [30, 62].

Even though the rDNA promoters among eukaryotes have a similar bipartite arrangement of cis-regulatory elements, it is difficult to find a conserved consensus sequence within these elements [63]. Alignment of rDNA promoter sequences across a wide range of species reveals a lack of sequence conservation within the essential CE [63]. Although the promoter sequences themselves do not share homology, analysis of rDNA promoters from species encompassing the prominent kingdoms of life have been shown to share conserved structural features [64, 65]. Studies have shown that rDNA promoters share intrinsic curvature and kinks [63–67] and that these structural signatures are important for transcription factor promoter recognition [68]. This has been further supported in recent cryo-EM structures of the Pol I promoter that revealed several structural features within the CF binding site [48]. For instance, the CF binding site contains two kinks of ~45° and ~35° near positions −16 and −21, respectively [48]. DNA structure analysis of rDNA promoters from other species predicted similar curvature and bending [64, 66]. Based on these findings, current models propose that CF and its orthologs likely use structural features rather than a precise DNA sequence during promoter recognition [63, 64, 67, 68].

Here we describe the DNA binding preferences of the yeast Pol I initiation factor, CF. Our results reveal unique features of the CF complex binding to the rDNA promoter, such as its preference for the GC-minor groove, and we define the minimal CE necessary and sufficient for CF binding. Despite a lack of DNA sequence conservation, we show that yeast CF can bind to the human CPE in vitro and that the human anti-cancer drug CX-5461 inhibits CF binding. Finally, we show that the human CPE can functionally replace the yeast CE in vivo. Overall, these studies provide new insights into the promoter features required for CF binding and suggest the possibility of a conserved binding mechanism across species from yeast to humans.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Expression and Purification of recombinant Core Factor

Core Factor (CF) was expressed as previously described [46, 48] with the following modifications. Briefly, CF was expressed from the pET-Duet CF vector containing His6-Rrn7-Rrn11-His6-Rrn6 in LOBSTR-BL21(DE3)-RIL Escherichia coli cells. Recombinant CF protein was expressed in Autoinducing Terrific Broth (0.024% w/v tryptone, 0.048% yeast extract w/v, 0.4% v/v glycerol, 17 mM KH2PO4, and 72 mM K2HPO4) supplemented with 20 ml per liter ZY-5052 (25% v/v glycerol, 2.5% w/v glucose, and 10% w/v alpha lactose monohydrate) and 2mM MgSO4. Inoculated media was grown to an OD600 of 0.6 then shifted to 18°C overnight. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, pellets were washed in Tris-buffered saline (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl) supplemented with 1X PMSF and 1mM DTT and stored at −80°C. Approximately 50 grams of cells were thawed and resuspended in 5 ml per gram of Extraction Buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 500 mM KCl, 10 mM Imidazole, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol) and supplemented with 1X PMSF and 1 mM DTT. Lysozyme was added to resuspended cells at 1mg/mL and incubated on ice for 30 min. The cells were lysed by sonication using a Branson Sonifier 450 (VWR Scientific). The extract was clarified by centrifugation at 4°C for 30 min at 20,000 × g. The clarified extract was added to washed Ni-NTA Sepharose beads (Biotool) and incubated at 4°C overnight in batch. Protein bound beads were washed two times with high salt Wash Buffer (Extraction Buffer but with 1 M KCl) and two times with low salt Wash Buffer (Extraction Buffer but with 200 mM KCl). Bound proteins were eluted with 24 ml of Elution Buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 200 mM KCl, 200 mM Imidazole, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol). Eluted CF was then further purified over a HiTrap Heparin HP column (GE Healthcare) using a linear gradient of Buffer A (50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 200 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol) to Buffer B (Buffer A with 1 M KCl) over 10 column volumes. CF was eluted between 800–1000 mM KCl. Peak fractions were pooled, desalted in Buffer C (50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol) and concentrated using Amicon Ultra-100K filters (Millipore). Concentrated CF was then further purified over a HiTrap Q HP column (GE Healthcare) using a linear gradient of Buffer A to Buffer B (as described above). Protein eluted between 400–600 mM KCl. Peak fractions were pooled and concentrated using Amicon Ultra-100K filters (Millipore). CF was diluted in Buffer D (50mM HEPES pH 8.0, 200mM KCl, 5% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Tween-20) to 0.0135mg/mL, aliquoted and stored at −80°C.

2.2. PCR synthesis of Infrared-labeled EMSA probes

Infrared-labeled DNA probes were synthesized by PCR using KODX Hot Start polymerase (Millipore). Forward primer- EMSA-Cy55-IR-F: GGAAAAAAAATATACGCTAAGATTTTTGGAGAAT, reverse primer- UAS minus R: AAATTTTGTAAACTATTGTATTACTATTACACAG, pWT PI Pro used for Wild Type template, pCE PI Pro use for ΔCE template and pUAS PI Pro used for ΔUAS template. pHCE PI Pro used for hCPE template with forward primer: hCPE F2: CGGCGTGGTCGGTGACGCTGG and reverse primer- UASminus-Cy55-IR-R: AAATTTTGTAAACTATTGTATTACTATTACACAG. The human probe contains the entire CPE with flanking promoter regions on each side from −83 to +28 relative to the start site of transcription found at +1. PCR was carried out as follows: 94°C for 2 min, [98°C for 10 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, 68°C for 25 seconds] for 30 cycles, followed by a 68°C final extension for 2 min. Amplified products were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis using 4% TAE (40 mM Tris, 20 mM acetic acid, 1 mM EDTA) Certified™ Low Range Ultra agarose (BioRad) supplemented with Gel Red nucleic acid stain (Biotium). Electrophoresed PCR products were visualized using the LiCOR Odyssey FC scanner. Bands of interest were excised using a UV illuminator and gel purified using the E.Z.N.A Gel Extraction Kit (Omega Bio-Tek) following the manufacturers protocol.

2.3. Infrared labeling of EMSA probes

Complementary oligonucleotides were synthesized with the top strand containing a 5’ C6 amino ester modification (Sigma). We mixed the top oligo with an equal molar ratio IR-800 dye (LiCOR) in Phosphate buffered saline (10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl pH 7.4) and incubated for 6 hours protected from light. Next, we combined the labeled top strand with the complementary bottom strand and annealed them. Free dye and unannealed strands were removed by gel purification on a 4% Certified Low Range Ultra agarose gel (BioRad) in TAE buffer. The annealed strands were excised from the gel and extracted with a Nebulizer (Millipore) following the manufacturers protocol. The extracted probe was purified by ethanol precipitation and the DNA pellet was resuspended in EB buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5).

2.4. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays (EMSA)

Samples were prepared with 30 ng of infrared-labeled DNA probe and 0.05 total ug of CF protein in Gel Shift Buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 60 mM KCl, 5% Glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2) with a total reaction volume of 20 uL. CF titrations contained 0, 0.025, 0.05, and 1 ug of total protein. Recombinant CF and DNA probe were incubated at 25°C for 40–45 min shaking at 300 RPM in an Eppendorf Thermomixer F1.5. 15 uL of reaction was run on a 5% TBE gel (BioRad) in 1X TBE (0.089M Tris, 0.089M Boric acid, and 0.002M EDTA) and imaged on a LiCOR Odyssey FC imaging system. 0.025ug of Poly(dI:dC) was used as a non-specific competitor where indicated.

2.5. DNA competitor EMSAs.

Two annealing protocols were used to anneal complementary DNA competitor oligos. First, top and bottom strands were combined in equimolar amounts in Annealing Buffer (10mM Tris, pH 7.5–8.0, 50mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA) and placed in boiling water. Reactions were allowed to cool at ambient temperatures for at least 8 hours. Second, top and bottom strands were combined in equimolar amounts in Annealing Buffer (same as above) and placed in a thermocycler. Reactions were heated to 95°C for 3 mins, followed by a temperature decrease of 1°C/min until the reactions reached 12°C. EMSA were performed as described above with the following modifications. DNA probe was pre-incubated with competitor for 30 min prior to addition of CF. In a 15 uL reaction, 15 ng of probe and 30 pM of annealed competitor oligo (referred to as 1X) in Gel Shift buffer were mixed and incubated for 30 min with all components except CF, followed by 45 min after CF addition. Synthetic alternating DNA copolymers (InvivoGen) that include Poly(dG:dC), Poly(dA:dT), and Poly(dI:dC) were resuspended in EB buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5) to a stock centration of 1 mg/mL. Poly(dA:dT), Poly(dG:dC) and Poly(dI:dC) copolymers used in this study are approximately 200 base pairs, 400 base pairs and 75 base pairs, respectively.

2.6. DNA binding agent EMSAs.

A 1 M stock of Hoechst 33258 (Abcam) and Hoechst 33342 (Abcam) were prepared in deionized H2O and diluted to a working concentration of 1 mM. A 1 M stock of Methyl Green (Sigma) was prepared in deionized H2O and diluted to a working concentration of 1 mM. A 2 M stock of Chromomycin A3 (Abcam) was prepared in DMSO and diluted to a working concentration of 1 mM. CX-5461 powder (Adooq Bioscience) was resuspended in 50mM NaH2PO4 to a stock concentration of 10 mM.

2.7. Determining CF Binding Affinities

Binding affinities (Kd) were calculated using a previously described method [69]. Briefly, samples were prepared with 3 ng of infrared-labeled 800 DNA probe in Gel Shift Buffer (see section 2.4) with a final reaction volume of 30 uL. The yCE probe consists of the following 20 base pair annealed DNA oligonucleotides: top strand 5’-AGTGTGAGGAAAAGTAGTTG-3’, bottom strand 5’-CAACTACTTTTCCTCACACT-3’. The hCPE probe consists of the following 20 base pair annealed oligonucleotides: top strand 5’-CGAGTCGGCATTTTGGGCCG-3’, bottom strand 5’-CGGCCCAAAATGCCGACTCG-3’. CF titrations contained 0, 0.02, 0.04, 0.06, 0.08, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1 ug of total protein for the yCE probe while titrations for the hCPE probe contained 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 6.0, 8.0, and 10 ug of total protein. Recombinant CF and DNA probe were incubated at 25°C for 45min shaking at 300 RPM in an Eppendorf Thermomixer F1.5. 20 uL of reaction was run on a 5% TBE gel (BioRad) in TBE (see section 2.4) and imaged on a LiCOR Odyssey FC imaging system. Kd was calculated using the ratio of the bound band intensity (CF+DNA) to the total DNA intensity in each lane plotted against the concentration of CF for each sample. Best fit lines were generated using Prism 8 software, and the Kd calculated as the CF concentration in which the best fit line was valued at 0.5 on the Fraction Bound variable (Y-axis). Experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.8. In silico prediction and modeling of DNA structural features

The bendability and curvature plots were calculated using the bend.it® server [70] (http://pongor.itk.ppke.hu/dna/bend_it.html#/bendit_intro) with a window size of 3 base pairs . The curvature parameter was derived from DNaseI digestion. DNA models were generated using the model.it® server [70, 71] (http://pongor.itk.ppke.hu/dna/model_it.html#/modelit_intro) under the consensus (trinucleotide) parameter [72]. Base pairs were colored in PyMOL based on their bendability (orange) and curvature (blue) values derived from bend.it analysis. Darker colors correspond to higher values (more curved or flexible) while lighter colors correspond to lower values (more straight or rigid).

2.9. Yeast growth assays.

All rDNA reporter yeast strains used in this study were derived from KAY-488/NOY-890 (MATa ade2–1 ura3–1 trp1–1 leu2–3,112 his3–11 can1–100 rdnΔΔ::HIS3 carrying pRDN-hyg1 URA3) [73, 74]. We modified this strain to disrupt the HIS3 marker and replaced it with the TRP1 marker by PCR amplifying the TRP1 marker from a pRS304 vector with primers flanking the HIS3 open reading frame to create the following strain BAK-494 (MATa ade2–1 ura3–1 trp1–1 leu2–3,112 his3–11 can1–100 rdnΔΔ::TRP1 carrying pRDN-hyg1 URA3). The BAK-494 strain was transformed with various high copy number HIS3 marker Pol I reporter plasmids. Yeast cell viability assays were performed on glucose complete (GluC) lacking histidine (H) and tryptophan (W) plates with or without 1g/liter 5-fluoroorotic acid (FOA). Cells were spread onto plates in three-phase streaks and grown at 30°C to examine yeast cell growth.

CX-5461 growth assays were performed with yeast strain W3031a (MATa leu2–3,112 trp1–1 can1–100 ura3–1 ade2–1 his3–11,15) [75]. Cells were cultured overnight in YPAD (1% w/v yeast extract, 2% w/v peptone, 2% v/v glucose, 0.002% v/v adenine) at 30°C until saturated. Approximately 1 mL of saturated overnight culture was pelleted and washed two times in sterile, deionized H2O. Cells were resuspended in 1mL of fresh sterile, deionized H2O and prepared using 5-fold serial dilutions. It is worth noting that multiple attempts were made to prepare plates with CX-5461 in the media, but the drug consistently precipitated out of solution. Therefore, the drug was added directly to the cells in solution prior to spotting. Each dilution was supplemented with 0uM, 250uM or 500uM CX-5461. The 0uM dilution contained vehicle (50mM NaH2PO4) only. Cells were spotted onto YPAD plates and grown at 30°C to examine yeast cell growth.

3. Results

3.1. DNA Groove preference of CF binding

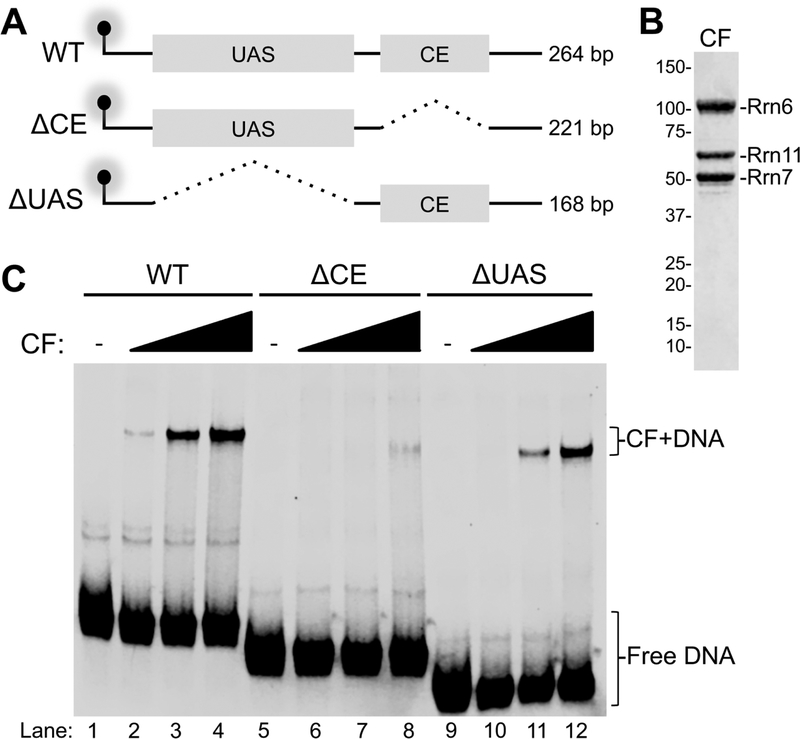

We studied the rDNA binding properties of yeast Core Factor (CF) by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). We synthesized infrared (IR) labeled rDNA promoter segments by PCR using an IR-labeled forward primer and unlabeled reverse primer. Three different IR probes were generated that include the entire wild type (WT) promoter from positions −189 to +75 and two promoter variants either lacking the CE (−38 to +5) or the UAS (−156 to −60) (Fig. 1A). We incubated our WT IR probe with increasing amounts of recombinant CF (Fig. 1B) and observed a shifted CF-DNA complex (Fig. 1C). Removal of the CE from the IR probe resulted in a significant reduction of the CFDNA complex (Fig. 1C), while CF still readily bound the IR probe lacking only the UAS (Fig. 1C). These results show that CF binding to the rDNA promoter is dependent on the presence of the CE. The ΔUAS probe was used hereafter to further examine CF DNA binding properties, as this smaller probe is sufficient for CF binding and has been previously shown to be sufficient for basal transcription initiation [47].

Figure 1. Yeast RNA polymerase I promoter elements necessary for CF DNA binding.

A. Representation of Pol I promoter templates used in this study. Pointed dashed lines indicate deleted regions of DNA. UAS, upstream activating sequence; CE, core element; WT, wild type; bp, base pairs. The glowing lollipops represent the location of the infrared label (IR). B. Representative Coomassie blue stained SDS-PAGE gel of purified CF protein used in this study. Molecular weight standards (kDa) depicted on the left. CF subunits Rrn6, Rrn11 and Rrn7 are indicated. C. Titration of CF with indicated IR-labeled EMSA probes. Poly(dI:dC) was used as a non-specific competitor.

Next, we characterized the groove binding preferences of CF. Using our EMSA system, we performed two types of competitor assays. We first tested the influence of different types of double-stranded, alternating copolymer competitor DNAs on CF-rDNA binding. We used three unlabeled competitor DNAs that include Poly(dA:dT), Poly(dG:dC) and Poly(dI:dC). Poly(dA:dT) contains a repetitive AT base pair sequence [76], and likewise Poly(dG:dC) contains a repetitive GC base pair [77] (Fig. 2A). Poly(dI:dC) is a hybrid copolymer containing the synthetic nucleotide inosine and mimics an AT-minor groove and GC-major groove [78, 79] (Fig. 2A). We preincubated our IR probe with the unlabeled competitor DNA before the addition of CF (Fig. 2B). We observe that CF binding is modestly competed away with Poly(dA:dT) and is nearly insensitive to Poly(dI:dC), if not slightly enhanced (Fig. 2C, D). Poly(dG:dC) exhibited the most dramatic response and completely competed away CF binding (Fig. 2C, D). These results suggest that the GC-minor groove may be important for CF binding. We reason this based on a process of elimination as Poly(dI:dC), containing a GC-major groove, does not inhibit CF binding, leaving only the Poly(dG:dC) minor groove as the potential source of competition.

Figure 2. Effect of various DNA copolymers on yeast CF DNA binding.

A. Synthetic DNA competitors used in this study. Red circles indicate hydrogen bond acceptors. Blue circles indicate hydrogen bond donors. A, Adenine; T, Thymidine; I, Inosine; C, Cytosine; G, Guanine. B. Workflow of copolymer competitor EMSA. DNA copolymers and ΔUAS IR-labeled DNA were pre-incubated together for 30 minutes prior to addition of recombinant CF. C. Effect of titration of indicated DNA copolymers on CF DNA binding. Representative EMSA results are shown. An asterisk indicates non-specific DNA band. D. Line graph depicting the relative CF DNA binding quantitation after copolymer competition. All values shown are relative to CF DNA binding in the absence of copolymer, which is set at 100%. Error bars denote standard deviation of triplicate experiments.

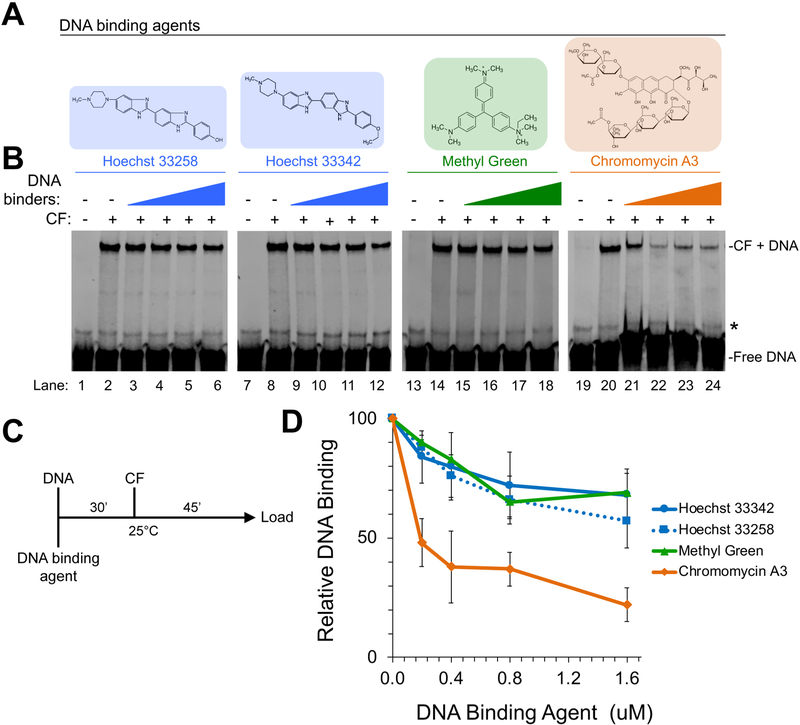

To test this model further, we used four different groove-binding chemical agents and assessed their effects on CF binding. These drugs include the GC-minor groove binding reagent Chromomycin A3 [80], the AT-minor groove binding agents Hoechst 33258 [81] and Hoechst 33342 [80], and the AT-major groove binding agent Methyl Green [82] (Fig. 3A) employing a similar binding scheme used for the copolymer competitor DNAs (Fig. 3C). We observed that Methyl Green and both Hoechst 33258 and Hoechst 33342 had very minimal impact on CF binding (Fig. 3B, D), but increasing amounts of Chromomycin A3 inhibited CF rDNA binding (Fig. 3B, D). Taken together, we can infer that the GC-minor groove plays a vital role in CF rDNA binding. These results are in agreement with previous studies that demonstrate the orthologous CF complex of Acanthamoeba castellani, TIF-1B, primarily interacts with the minor groove of promoter DNA [68].

Figure 3. Effect of various DNA binding agents on yeast CF DNA binding.

A. Structures of DNA binding agents used in this study. B. Effect of titration of the indicated DNA binding agents on CF DNA binding. Representative EMSA results are shown. An asterisk indicates non-specific DNA band. C. Workflow of DNA binding agent EMSA assay. DNA binding agent and ΔUAS IR-labeled DNA were pre-incubated together for 30 min prior to addition of recombinant CF. D. Line graph depicting the relative CF DNA binding quantitation after DNA binding agent competition. All values shown are relative to CF DNA binding in the absence of DNA binding agent, which is set at 100%. Error bars denote standard deviation of triplicate experiments.

3.2. Minimal CF binding region within the yeast CE

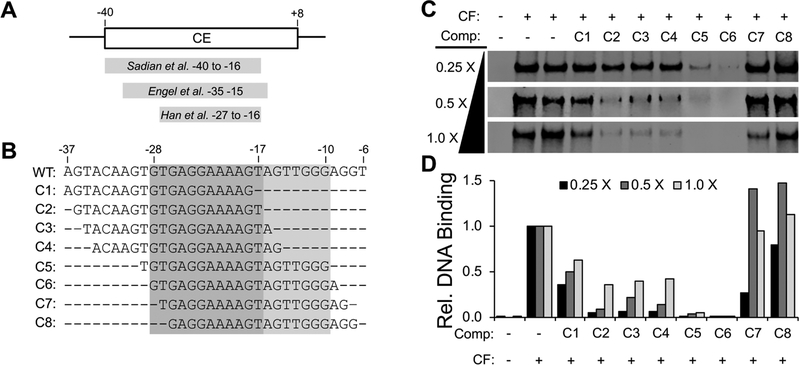

To determine the minimal CF binding region within the CE, we used our EMSA-based competitor approach. Available cryo-EM structures of the CF-DNA complex suggest that a region between −40 and −15 may be necessary for CF binding [24, 25, 48] (Fig. 4A). In addition, previous biochemical studies defined a region within the yeast CE between −28 to +8 is necessary for Pol I promoter activity [15–17]. However, the minimal region of the CE essential for CF binding remains unclear. We designed a series of 20 base pair unlabeled competitors (C1–C8) that incrementally scan the length of the CE to resolve the 5’ and 3’ boundaries necessary for CF binding (Fig. 4B). We tested three different concentrations of our competitors to assess their effect on CF binding to our IR-labeled promoter probe. We note that incubating DNA with CF before or after addition of competitor yields similar results, suggesting that order of addition of competitor does not matter (Fig. S1). At the two highest competitor concentrations, five competitors (C2–C6) reduced CF binding to the IR probe, with C5 and C6 showing the strongest competition (Fig. 4C, D). At the lowest competitor concentration, both C5 and C6 continued to compete away CF from our IR-probe, whereas C2–C4 exhibited reduced competition (Fig. 4C, D). Our results indicate a defined 5’ boundary at the −28 position given the dramatic loss in competition between competitors C6 and C7. The 3’ boundary is less defined compared to the 5’ boundary. For instance, there is loss in competition between C4–C5 and again between C1 and C2, suggesting the boundary lies between the −10 to - 17 position, thereby narrowing down the CF binding site within a 19 base pair window spanning from −28 to −10.

Figure 4. Defining the boundaries of the yeast CE.

A. Diagram of the yeast CE along with the regions experimentally shown to contact CF in three independent cryo-EM structures. B. Sequences of competitors used to define the boundaries of the Core Element (CE). WT, wild type sequence in which competitors are based upon. Dashed lines indicate excluded base pairs. Position within Pol I promoter relative to the transcription start site are listed above respective base pairs. Gray shaded area the region most important for CF binding and the lighter gray area to a lesser extent. C. Effect of indicated yeast CE competitors on CF DNA binding to the yeast ΔUAS IR-labeled promoter. Representative EMSA results are shown using a range of competitor concentrations. D. Bar graph below the EMSA results depict the relative CF DNA binding (R.B.) quantitation after unlabeled competition experiments. All values shown are relative to CF DNA binding in the absence of competitor oligos which is set at 1.0.

To further refine the boundaries of CF binding, we designed a series of mini competitors (mC1-mC20). Using the 19 base pair window elucidated above, we progressively removed base pairs from the 5’ or 3’ end (Fig. 5A). For the series of mini competitors that removed base pairs from the 5’ end (mC1–8), we observed a complete loss in competition upon removal of the −28 base pair (Fig. 5B). These results are in agreement with our larger competitors that showed a well-defined 5’ boundary at the −28 position. For mini competitors that removed base pairs at the 3’ end (mC9–20), mC9–15 retained a significant level of competition with 3’ boundaries spanning from −10 to −17, respectively (Fig. 5B). We observed a markedly reduced level of competition with mC16 followed by complete loss of competition for mC17–20 (Fig. 5B). Together these findings further refine the minimal CF binding site to a 12 base pair window between positions −28 and −17.

Figure 5. Defining the minimal yeast CE.

A. Sequence of competitors used to define the minimal yeast CE. Dashed lines indicate excluded base pairs. Position within Pol I promoter relative to the transcription start site are listed above respective base pairs. Gray shaded area indicates the minimal CE. B. Effect of indicated mini competitors on CF ΔUAS IR-labeled DNA binding. Representative EMSA results are shown. C. CF binding to the indicated mini IR-labeled EMSA probes. The 5’ and 3’ boundaries of these probes are indicated. D. Effect of removing the minimal CF binding site (−28 to - 17) in the ΔUAS IR probe on CF DNA binding. Poly(dI:dC) was used as a non-specific competitor for panels C and D. Bar graph below the EMSA results depict the relative CF DNA binding (R.B.) quantitation in which all values shown are relative to CF DNA binding in the absence of competitor oligos which is set at 1.0.

To test the minimal CF binding site more directly, we IR-labeled several mini probes spanning the −29 to −17 position. We detected maximal CF binding to the mini probes spanning the −28 to −17 and −29 to −18 (Fig. 5C), whereas we observe markedly reduced CF binding to all the remaining IR-labeled mini probes (Fig. 5C). For instance, the mini probe −27 to −17 exhibited a significantly lower level of CF binding, while the −26 to −17 mini probe showed nearly undetectable CF binding (Fig. 5C). Likewise, we observed a similar pattern in the mini probes that pass the 3’ boundary, which include the −29 to −19 and −29 to −20 probes (Fig. 5C). Finally, we designed an IR-labeled EMSA probe devoid of the −28 to −17 base pairs to test whether this minimal 12 base pair element is necessary for CF binding. As expected, CF binding to the EMSA probe lacking the minimal CE was significantly reduced compared to the WT probe (Fig. 5D). Our findings show that CF targets a minimal 12 base pair segment within the larger CE. Furthermore, these results parallel previous yeast Pol I studies that used linker scanning mutagenesis to demonstrate that transcriptional activity is completely abolished in promoters lacking the −28 to −17 region of the CE [17]. Taken together, these studies highlight the importance of this 12 base pair region of the CE that is required for both CF binding and Pol I promoter activity [15–17].

3.3. Yeast CF binds to the human promoter

Yeast and human rDNA promoters are very divergent at the sequence level [63], but they have similar structural signatures in terms of their intrinsic bendability and curvature (Fig. 6). For instance, the yeast and human core elements center around a highly curved and rigid region, denoted by a conspicuous peak in the curvature plot and valley in the bendability plot, which is flanked by more flexible and straight segments on either side (Fig. 6). However, relative to the transcription start sites in each organism, this curved and rigid region is located further downstream in the human promoter compared to the yeast promoter. Spacing between promoter elements and the transcription start site is often vital for transcriptional activity [27, 29, 83] but it is unclear if this may play a role in the species-specific differences between yeast and human Pol I promoters.

Figure 6. DNA structural features of the yeast CE and human CPE.

A-B. Curvature and bendability values of the (A) yeast and (B) human promoters. Gray shaded area indicates the minimal CE or CPE. C-D. Generated structures of the (C) yeast and (D) human promoters. Position within Pol I promoter relative to the transcription start site are listed above respective base pairs. Base pairs colored by curvature (blue) and bendability (orange) values shown in Panels A and C for respective promoters. Darker colors correspond to higher bendability and curvature vales.

CF and its human ortholog SL1 may target a conserved DNA structure rather than a precise sequence [63, 64]. If the yeast and human promoters shared a conserved structure, it is possible that yeast CF could target the human promoter and vice versa. To test this, we first designed a series of human competitor probes spanning the entire CPE that is analogous to the yeast CE. A titration of unlabeled human rDNA promoter containing the entire CPE competes away CF from our IR-labeled yeast rDNA promoter in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7A). Likewise, yeast CF can bind directly to an IR-labeled human promoter probe (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, CF binding to human promoter probe was dependent on the human CPE as deletion of this element substantially reduced binding (Fig. 7C). Together these results show that even with different core promoter sequences, the yeast CF can recognize and bind to the human promoter. Earlier reports localize the region crucial for human Pol I promoter activity to reside within positions −43 and +8 [27, 29]. We designed a series of 20 base pair human CPE competitors that span from −35 to −3 to further refine the region important for CF binding and competition (Fig. 7D). Among this series of competitors, H8 and H9 inhibited CF binding the most, as evident by the near absence of detectable CF-DNA complex (Fig. 7E). Human competitors H8 and H9 contain CPE base pairs −28 to −9 and −27 to −8, respectively, and they both encompass the shared bendability and curvature signature seen in the yeast and human promoters. The 3’ boundary is less defined, but there is an apparent reduction in competition between human competitors H4 and H5 corresponding to base pairs −32 to −13 and −31 to −12 (Fig.7E). Together, these competition studies would place the CF binding site between positions −27 to −12 within the human CPE.

Figure 7. Yeast CF binds to the human CPE.

A. Effect of human CPE competitor titration on yeast CF ΔUAS IR-labeled DNA binding. An asterisk indicates non-specific DNA band. B. Titration of yeast CF with the IR-labeled human rDNA promoter probe. C. Effect of removal of the CPE from the human rDNA promoter probe on CF DNA binding. Poly(dI:dC) was used as a non-specific competitor for panels B and C. D. Sequence of competitors used in this study. WT, wild type sequence in which competitors are based upon; Dashed lines indicate excluded base pairs. Position within human Pol I promoter relative to the transcription start site are listed above respective base pairs. Gray shaded area indicates minimal CPE. E. Effect of indicated human CPE competitors on CF DNA binding to the IR-labeled human rDNA promoter. Representative EMSA results are shown. Bar graphs below the EMSA results depict the relative CF DNA binding (R.B.) quantitation. All values shown are relative to CF DNA binding in the absence of competitor oligos which is set at 1.0.

Next, we further refined the human CPE boundaries for CF binding. We designed a series of mini human competitors (mH1-mH20). Using the 19 base pair window starting from the −27 position and ending with the −9 position, we progressively removed base pairs from the 5’ or 3’ ends (Fig. S2A). The most effective competitor was mH1 which contained the entire 19 base pair sequence (Fig. S2B). We observed a loss in competition as we removed base pairs from the 5’ end downstream of the −27 position (Fig. S2B). For the 3’ boundary, we observe a loss in competition between mH15 and mH16 that corresponds to the −27 to −13 and −27 to −14 base-pairs, respectively (Fig. S2B). These results agree well with our larger competitors and refine the minimal CF binding site within the human CPE between the −27 to −13 positions.

Since CF binds both the yeast and the human rDNA core elements, we next compared the binding affinity of CF to these elements. We employed our EMSA system to determine the ratio at which approximately 50% of the probe is bound by CF, referred to as the binding affinity (Kd) [69]. We show that CF has an apparent Kd of ~0.4 pM for the yeast promoter (Fig. S3A, C) and ~3 pM for the human promoter (Fig. S3B, D). The differences in Kd are not surprising as one would anticipate a yeast protein will bind its own promoter better than that of heterologous species. Therefore, we conclude that CF has a very high affinity for its cognate yeast promoter and a slightly lower, yet still quite high, binding affinity for the human promoter.

3.4. CX-5461 inhibits CF binding to yeast CE and human CPE

CX-5461 is an anti-cancer drug proposed to inhibit Pol I transcription initiation by destabilizing PIC formation [84, 85]. Specifically, CX-5461 binds to GC-rich sequences in the human rDNA promoter, and may stabilize G-quadruplex structures found in this region and elsewhere [86, 87]. Stabilization of G-quadruplex structures may directly interfere with SL1 DNA binding activity by preventing recognition of the CPE. Since CF binds to the human promoter, we asked if CX-5461 could also impact yeast CF function. Recent studies have shown that yeast cell growth is sensitive to CX-5461, suggesting that CX-5461 may also inhibit yeast Pol I transcription [86]. We treated yeast cells with CX-5461 and found that cell growth was sensitive to CX-5461 in a dose-dependent manner, as previously described (Fig. 8A). To test if a similar mechanism of action is employed by CX-5461 in the yeast system, we tested whether CX-5461 could directly inhibit CF binding in our EMSA conditions. We preincubated our IR-labeled EMSA probe with increasing amounts of CX-5461 (Fig. 8B) and found that CF binding to the yeast promoter was severely inhibited at all concentrations tested (Fig. 8C, D). Likewise, CF binding to the human promoter was similarly inhibited (Fig. 8C, D). These findings are consistent with CX-5461 blocking SL1’s DNA binding through a fundamental feature that is conserved in CF.

Figure 8. CX-5461 inhibits CF binding to the yeast CE and human CPE.

A. Spot assays of yeast treated with increasing amounts of CX-5461. B. Workflow of CX-5461 binding assays. C. Effect of CX-5461 titration on CF DNA binding to indicted yeast ΔUAS and human IR-labeled promoter probes. Representative EMSA results are shown. D. Relative CF DNA binding quantitation of EMSA results. All values shown are relative to CF DNA binding in the absence of CX-5461, which is set at 100%. Error bars denote standard deviation of duplicate experiments.

3.5. The human CPE functions in yeast

To examine the functional conservation between yeast and human core elements more closely, we employed a yeast strain containing a complete deletion of the chromosomal rDNA repeats [74]. This strain subsists on a high copy number plasmid containing a copy of the rDNA locus and a URA3 marker, allowing its use in plasmid shuffle assays [74]. We used this strain to test various high copy number Pol I reporter plasmids containing the rDNA locus under control of the yWT Pol I promoter or mutant variants. When this strain is transformed with the yWT Pol I reporter plasmid, growth is rescued on the FOA-containing plates (Fig. 9B), unlike the empty vector (EV) or mutant Pol I reporter variants lacking the entire CE (yΔCE) region or minimal CF binding site (yΔmCE) (Fig. 9B). These results complement our in vitro EMSA studies, further showing that the minimal CF binding site is essential in the context of yeast in vivo.

Figure 9. The human CPE functionally replaces the yeast CE.

A. Diagram of the Pol I promoter reporter constructs used in this study. Pointed dashed lines indicate deleted regions of DNA. The UAS and CE are depicted as gray boxes and human CPE is shown as a dark gray box. B. The indicated Pol I reporter constructs were transformed into the rDNA deletion shuffle strain and streaked onto Glucose complete (GluC) plates lacking histidine (H) and tryptophan (W) with or without FOA to select for cells having lost the Pol I URA3 marked plasmid. Bendability (C) and curvature (D) values for promoter constructs. Position within Pol I promoter relative to the transcription start site listed below respective base pairs. Gray shaded area in yWT indicates the minimal CE region bound by yeast CF. The gray boxes for yhCPE1 and yhCPE2 denote the location where the human CPE sequence was inserted into each construct. E-F. Modeled structures of promoter constructs. Numbers designate the position of the base pairs relative to the transcription start site. Base pairs colored by derived (E) bendability (orange) and (F) curvature (blue) values, respectively.

We then humanized the yeast Pol I promoter by designing hybrid promoters the yeast CE was replaced with the human CPE. As previously indicated, the human CPE is closer to the transcription start site compared to the yeast promoter [27, 29]. Using the minimal human CF binding site we defined above, we inserted the minimal human CPE in two positions: one resembling the human CPE position (yhCPE1) and the other more similar to the yeast CE position (yhCPE2) (Fig. 9A). The predicted curvature and bendability profiles showed that yhCPE2 more closely follows the profiles of the yWT promoter than yhCPE1 (Fig. 9C–D). In particular, the highly rigid region in yhCPE2 is located in the same position and patterns near identically to the yWT promoter. In contrast, the equivalent structural features of yhCPE1 are shifted two base pairs downstream. Modeling the DNA structures of these promoters and coloring their bendability and curvature values at the base pair level visually highlights the overlapping peaks of rigidity and curvature in all three promoter constructs and demonstrates the preserved spacing between the CE and the transcription start site in our yWT and yhCPE2 promoter constructs compared to yhCPE1 (Fig. 9E–F).

When these humanized Pol I reporters were transformed into the rDNA deletion strain and grown on FOA-containing plates, only the yhCPE2 cells were viable (Fig. 9B). These results show that the human CPE can functionally replace the yeast CE in a position-dependent manner. This positional-dependence may help explain the difference in species-specificity, as Pol I promoters from other organisms may have different promoter element positioning [88]. Additionally, our findings suggest that using the structural profiles rather than sequence is a much better means to align Pol I promoters. More broadly, these in vivo findings further suggest that the yeast CF and human SL1 likely use a conserved binding mechanism despite the lack of sequence conservation.

4. Discussion

Here, we characterized the DNA binding properties of yeast RNA polymerase I CF. We found that CF has a preference for GC-rich DNA, with particular affinity to the GC-minor groove. We also found that the yeast CF was able to bind to the human rDNA promoter in a CPE-depenedent manner. In addition, we show that the human anti-cancer drug CX-5461 inhibits CF from binding to both the yeast and human rDNA promoters, which further shows that CF and SL1 share common features in their binding mechanisms. Finally, we show that the human CPE can functionally replace the yeast CE in vivo in a positional-dependent manner, suggesting a potential mechanism of species-specificity between CF and SL1.

Few DNA binding proteins target the minor groove and even less target the GC-minor groove [89, 90]. One reason for this is that the GC-minor groove is more narrow than the AT-minor groove [89]. However, localized bending and kinking of DNA can widen the GC-minor groove, exposing more points of contact for protein interactions [91]. In agreement with our findings, previous studies in A. castellani showed that the CF ortholog in this system also exhibited a preference for the GC-minor groove [64]. Interestingly, the A. castellani CF ortholog is more similar to SL1 than CF, as it contains TBP as a stable member of its complex [92]. TBP is an AT-minor groove binding protein and could contribute to the minor groove binding activity of the A. castellani CF ortholog [64, 90, 93]. However, since yeast TBP is not a stable CF subunit [3, 4] and is absent in our CF binding assays, we propose that the GC-minor groove binding activity is not attributed to TBP but rather CF and its orthologous SL1 subunits. Furthermore, the unique path of Pol I promoter DNA in the PIC with its associated bends and kinks likely contributes to the ability of CF to target the GC-minor groove [24, 25, 48]. Higher resolution structures of CF bound to DNA will be necessary to explore the groove preference in promoter recognition. Although not commercially available, future studies employing the synthesis of pyrrole-imidazole polyamides engineered to target the minor groove DNA in a sequence-specific manner [94] would more precisely identify which minor groove(s) of the promoter are required for CF binding.

Targeting the GC-minor groove may be a shared feature among CF and its Pol II and III paralogs, TFIIB and Brf1, respectively [95–97]. For instance, TFIIB recognizes two GC-rich elements flanking the TATA box called the TFIIB recognition elements (BRE) [97]. TFIIB contacts the upstream BRE via the major groove and contacts the downstream BRE via the minor groove [96]. Based on current Pol I PIC structures, CF contacts both the major and minor groove of the CE [24, 25, 48], but it is more likely that the GC-minor groove plays a more significant role in CF binding. These observed commonalities could imply that CF and its related Pol II and III paralogs utilize a more structure-based DNA binding mechanism to bind their respective target DNAs. The Pol I core elements contain several GC base pairs, but it is presently unclear in the current near atomic structures which nucleotides make contact with CF and play an essential role in binding. Understanding these precise contacts and their functional relevance will be critical for the development of new strategies to target these interactions in disease.

Our studies are consistent with a model in which DNA structural features play a defining role in CF, and likely SL1, promoter recognition [24, 64, 65, 67]. The rDNA promoters across eukaryotic species are poorly conserved at the sequence level [63]. Strikingly, pairwise alignment of the core elements between yWT and yhCPE2 only show conservation of two guanines at the −26 and −18 positions on the non-template strand. However, the bendability and curvature profiles of both promoter elements share key structural patterns. For example, the highly rigid region in the rDNA promoters is the result of the poly-A and poly-T tracts in the yeast CE and human CPE, respectively [72]. Our studies are also consistent with previous domain swapping studies that showed that the DNA binding regions of CF and SL1 are functionally compatible in the context of yeast [40]. Specifically, the N-terminal half of yeast Rrn7, containing the zinc ribbon through the DNA binding cyclin folds, can be replaced by the orthologous domains of human TAF1B [40]. These findings demonstrate that Rrn7 and TAF1B, while only sharing 14% protein sequence identity, are functionally similar [40, 41, 50]. Together our findings help explain how CF recognizes the human CPE despite low sequence identity between both CF and SL1 and their target promoters.

Humanization of the yeast rDNA promoter presented here suggests that the position of the promoter elements may explain the species-specific differences observed in cross-organismal Pol I studies [30, 54, 55]. By experimentally and computationally defining the precise boundaries of the yeast CE and human CPE, we were able to rationally design a transcriptionally active yeast Pol I promoter with a human CPE. Functional activity of the human CPE in the yeast Pol I promoter exhibited a positional-dependence, requiring a shift of two base pairs upstream from the yeast transcription start site compared to its natural position in the human promoter. These findings suggest that pairwise comparison of Pol I core promoter elements by DNA sequence alone will likely lead to misalignment, while DNA structural features serve as better guides for accurate promoter alignment and comparison.

This positional-dependence suggests differences in the stereospecific placement of promoter elements contributes to Pol I promoter species-specificity [64, 88], rather than the Pol I factors themselves. Previous studies in mice found that guanines (G’s) located at −7, −16, and −25 are important for in vitro transcription [98]. What makes these particular G’s interesting is their conservation between mammalian systems and their positions on the same helical-face of the promoter. In yeast, only the −7 position contains a G. However, 1–2 base pairs upstream from each of these positions in yeast lies a G, suggesting their helical face is maintained and agrees well with our humanized yeast rDNA promoters that require a 2 base pair upstream shift for functional activity in yeast.

Another example of Pol I species stereospecificity are studies comparing mouse and frog rDNA promoters. Mouse Pol I factors efficiently transcribe frog rDNA, but initiate transcription at the −4 position [99]. Deletion or insertion of half a helical turn between the UCE and CPE in the frog rDNA promoter ameliorates the downstream shift in the transcription initiation site, allowing the mouse factors to transcribe efficiently at the correct +1 position [88], Similar observations were noted in the rat model system, where full helical turn insertions and deletions between the UPE and CPE were tolerated [83].

Future experiments focused on understanding the compatibilities between the Pol I transcription systems of yeast, humans, and other species are needed to test this model further. However, it will be necessary to devise a more robust method to isolate functionally active SL1. Ultimately, understanding the structural aspects of the Pol I system in humans and other higher eukaryotes will likely reveal more clues on the mechanisms that control species-specificity. Likewise, further exploration of rDNA promoter conservation within the fungi kingdom may reveal clues into the sequence and structural features CF uses to recognize the CE.

The ability of CX-5461 to inhibit CF binding to DNA closely resembles previous results for human SL1 [84]. Coupled with the shared binding mechanism between these orthologous factors, our findings suggest yeast could serve as a valid model in studying how to target dysregulated Pol I transcription in cancer. With its tractable genetics and screens, the yeast model system offers a powerful means to investigate the mechanisms of Pol I based anti-cancer compounds. We anticipate that our findings presented here will help initiate future studies in the yeast system to discover novel approaches and to improve upon existing strategies targeting aberrant Pol I transcription in cancer.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Yeast CF binds preferentially to the GC-minor groove.

A minimal 12 base pair sequence of the yeast CE is required for CF DNA binding.

Yeast CF can bind the human rDNA promoter in a CPE-dependent manner.

CX-5461 inhibits yeast CF from binding to yeast and human rDNA promoters.

The human CPE can functionally replace the yeast CE in vivo.

Acknowledgements

We thank Knutson lab members for their critical review of this manuscript. We also thank the Asano laboratory (Kansas State Univ.) for kindly providing the Δrdn deletion yeast strain. This work was supported by B.A.K. grants from the US National Institutes of Health NCI (5K22CA184235), a Sinsheimer Scholar award from the Alexandrine and Alexander L. Sinsheimer Fund, Central New York Community Foundation, Joseph C. George Fund, Virginia Simons & Dr. C. Adele Brown, and Carol Baldwin Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Roeder RG and Rutter WJ, Multiple forms of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase in eukaryotic organisms. Nature, 1969. 224(5216): p. 234–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodfellow SJ and Zomerdijk JC, Basic mechanisms in RNA polymerase I transcription of the ribosomal RNA genes. Subcell Biochem, 2013. 61: p. 211–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneider DA, RNA polymerase I activity is regulated at multiple steps in the transcription cycle: recent insights into factors that influence transcription elongation. Gene, 2012. 493(2): p. 176–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reeder RH, Regulation of RNA polymerase I transcription in yeast and vertebrates. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol, 1999. 62: p. 293–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moss T, et al. , A housekeeper with power of attorney: the rRNA genes in ribosome biogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2007. 64(1): p. 29–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woolford JL Jr. and Baserga SJ, Ribosome biogenesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics, 2013. 195(3): p. 643–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williamson D, et al. , Nascent pre-rRNA overexpression correlates with an adverse prognosis in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer, 2006. 45(9): p. 839–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dauwerse JG, et al. , Mutations in genes encoding subunits of RNA polymerases I and III cause Treacher Collins syndrome. Nat Genet, 2011. 43(1): p. 20–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker-Kopp N, et al. , Treacher Collins syndrome mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae destabilize RNA polymerase I and III complex integrity. Hum Mol Genet, 2017. 26(21): p. 4290–4300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bywater MJ, et al. , Dysregulation of the basal RNA polymerase transcription apparatus in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer, 2013. 13(5): p. 299–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hannan KM, et al. , Dysregulation of RNA polymerase I transcription during disease. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2013. 1829(3–4): p. 342–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahn S, Structure and mechanism of the RNA polymerase II transcription machinery. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2004. 11(5): p. 394–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu X, et al. , Structure of an RNA polymerase II-TFIIB complex and the transcription initiation mechanism. Science, 2010. 327(5962): p. 206–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kostrewa D, et al. , RNA polymerase II-TFIIB structure and mechanism of transcription initiation. Nature, 2009. 462(7271): p. 323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choe SY, Schultz MC, and Reeder RH, In vitro definition of the yeast RNA polymerase I promoter. Nucleic Acids Res, 1992. 20(2): p. 279–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musters W, et al. , Linker scanning of the yeast RNA polymerase I promoter. Nucleic Acids Res, 1989. 17(23): p. 9661–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulkens T, et al. , The yeast RNA polymerase I promoter: ribosomal DNA sequences involved in transcription initiation and complex formation in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res, 1991. 19(19): p. 5363–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aprikian P, Moorefield B, and Reeder RH, New model for the yeast RNA polymerase I transcription cycle. Mol Cell Biol, 2001. 21(15): p. 4847–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steffan JS, et al. , The role of TBP in rDNA transcription by RNA polymerase I in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: TBP is required for upstream activation factor-dependent recruitment of core factor. Genes Dev, 1996. 10(20): p. 2551–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siddiqi I, et al. , Role of TATA binding protein (TBP) in yeast ribosomal dna transcription by RNA polymerase I: defects in the dual functions of transcription factor UAF cannot be suppressed by TBP. Mol Cell Biol, 2001. 21(7): p. 2292–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackobel AJ, et al. , Breaking the mold: structures of the RNA polymerase I transcription complex reveal a new path for initiation. Transcription, 2018. 9(4): p. 255–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moorefield B, Greene EA, and Reeder RH, RNA polymerase I transcription factor Rrn3 is functionally conserved between yeast and human. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2000. 97(9): p. 4724–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peyroche G, et al. , The recruitment of RNA polymerase I on rDNA is mediated by the interaction of the A43 subunit with Rrn3. Embo j, 2000. 19(20): p. 5473–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engel C, et al. , Structural Basis of RNA Polymerase I Transcription Initiation. Cell, 2017. 169(1): p. 120–131.e22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadian Y, et al. , Structural insights into transcription initiation by yeast RNA polymerase I. Embo j, 2017. 36(18): p. 2698–2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blattner C, et al. , Molecular basis of Rrn3-regulated RNA polymerase I initiation and cell growth. Genes Dev, 2011. 25(19): p. 2093–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haltiner MM, Smale ST, and Tjian R, Two distinct promoter elements in the human rRNA gene identified by linker scanning mutagenesis. Mol Cell Biol, 1986. 6(1): p. 227–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Learned RM, Cordes S, and Tjian R, Purification and characterization of a transcription factor that confers promoter specificity to human RNA polymerase I. Mol Cell Biol, 1985. 5(6): p. 1358–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones MH, Learned RM, and Tjian R, Analysis of clustered point mutations in the human ribosomal RNA gene promoter by transient expression in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1988. 85(3): p. 669–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heix J and Grummt I, Species specificity of transcription by RNA polymerase I. Curr Opin Genet Dev, 1995. 5(5): p. 652–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller KG, Tower J, and Sollner-Webb B, A complex control region of the mouse rRNA gene directs accurate initiation by RNA polymerase I. Mol Cell Biol, 1985. 5(3): p. 554–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cassidy B, Haglund R, and Rothblum LI, Regions upstream from the core promoter of the rat ribosomal gene are required for the formation of a stable transcription initiation complex by RNA polymerase I in vitro. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1987. 909(2): p. 133–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith SD, et al. , Transcription from the rat 45S ribosomal DNA promoter does not require the factor UBF. Gene Expr, 1993. 3(3): p. 229–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bell SP, Jantzen HM, and Tjian R, Assembly of alternative multiprotein complexes directs rRNA promoter selectivity. Genes Dev, 1990. 4(6): p. 943–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Sullivan AC, Sullivan GJ, and McStay B, UBF binding in vivo is not restricted to regulatory sequences within the vertebrate ribosomal DNA repeat. Mol Cell Biol, 2002. 22(2): p. 657–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hempel WM, et al. , The species-specific RNA polymerase I transcription factor SL-1 binds to upstream binding factor. Mol Cell Biol, 1996. 16(2): p. 557–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedrich JK, et al. , TBP-TAF complex SL1 directs RNA polymerase I preinitiation complex formation and stabilizes upstream binding factor at the rDNA promoter. J Biol Chem, 2005. 280(33): p. 29551–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bell SP, et al. , Functional cooperativity between transcription factors UBF1 and SL1 mediates human ribosomal RNA synthesis. Science, 1988. 241(4870): p. 1192–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller G, et al. , hRRN3 is essential in the SL1-mediated recruitment of RNA Polymerase I to rRNA gene promoters. Embo j, 2001. 20(6): p. 1373–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knutson BA and Hahn S, Yeast Rrn7 and human TAF1B are TFIIB-related RNA polymerase I general transcription factors. Science, 2011. 333(6049): p. 1637–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knutson BA and Hahn S, TFIIB-related factors in RNA polymerase I transcription. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2013. 1829(3–4): p. 265–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boukhgalter B, et al. , Characterization of a fission yeast subunit of an RNA polymerase I essential transcription initiation factor, SpRrn7h/TAF(I)68, that bridges yeast and mammals: association with SpRrn11h and the core ribosomal RNA gene promoter. Gene, 2002. 291(1–2): p. 187–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin CW, et al. , A novel 66-kilodalton protein complexes with Rrn6, Rrn7, and TATA-binding protein to promote polymerase I transcription initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol, 1996. 16(11): p. 6436–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lalo D, et al. , RRN11 encodes the third subunit of the complex containing Rrn6p and Rrn7p that is essential for the initiation of rDNA transcription by yeast RNA polymerase I. J Biol Chem, 1996. 271(35): p. 21062–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bedwell GJ, et al. , Efficient transcription by RNA polymerase I using recombinant core factor. Gene, 2012. 492(1): p. 94–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knutson BA, et al. , Architecture of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNA polymerase I Core Factor complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2014. 21(9): p. 810–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keener J, et al. , Reconstitution of yeast RNA polymerase I transcription in vitro from purified components. TATA-binding protein is not required for basal transcription. J Biol Chem, 1998. 273(50): p. 33795–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han Y, et al. , Structural mechanism of ATP-independent transcription initiation by RNA polymerase I. Elife, 2017. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Comai L, Tanese N, and Tjian R, The TATA-binding protein and associated factors are integral components of the RNA polymerase I transcription factor, SL1. Cell, 1992. 68(5): p. 965–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naidu S, et al. , TAF1B is a TFIIB-like component of the basal transcription machinery for RNA polymerase I. Science, 2011. 333(6049): p. 1640–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gorski JJ, et al. , A novel TBP-associated factor of SL1 functions in RNA polymerase I transcription. Embo j, 2007. 26(6): p. 1560–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Denissov S, et al. , Identification of novel functional TBP-binding sites and general factor repertoires. Embo j, 2007. 26(4): p. 944–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Safrany G, et al. , Structural determinant of the species-specific transcription of the mouse rRNA gene promoter. Mol Cell Biol, 1989. 9(1): p. 349–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rudloff U, et al. , TBP-associated factors interact with DNA and govern species specificity of RNA polymerase I transcription. Embo j, 1994. 13(11): p. 2611–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eberhard D and Grummt I, Species specificity of ribosomal gene transcription: a factor associated with human RNA polymerase I prevents transcription of mouse rDNA. DNA Cell Biol, 1996. 15(2): p. 167–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hannan R, et al. , Cellular regulation of ribosomal DNA transcription:both rat and Xenopus UBF1 stimulate rDNA transcription in 3T3 fibroblasts. Nucleic Acids Res, 1999. 27(4): p. 1205–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pikaard CS, et al. , rUBF, an RNA polymerase I transcription factor from rats, produces DNase I footprints identical to those produced by xUBF, its homolog from frogs. Mol Cell Biol, 1990. 10(7): p. 3810–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cavallini B, et al. , A yeast activity can substitute for the HeLa cell TATA box factor. Nature, 1988. 334(6177): p. 77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miesfeld R and Arnheim N, Species-specific rDNA transcription is due to promoter-specific binding factors. Mol Cell Biol, 1984. 4(2): p. 221–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dover GA and Flavell RB, Molecular coevolution: DNA divergence and the maintenance of function. Cell, 1984. 38(3): p. 622–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ganley AR and Kobayashi T, Highly efficient concerted evolution in the ribosomal DNA repeats: total rDNA repeat variation revealed by whole-genome shotgun sequence data. Genome Res, 2007. 17(2): p. 184–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carter R and Drouin G, The evolutionary rates of eukaryotic RNA polymerases and of their transcription factors are affected by the level of concerted evolution of the genes they transcribe. Mol Biol Evol, 2009. 26(11): p. 2515–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marilley M and Pasero P, Common DNA structural features exhibited by eukaryotic ribosomal gene promoters. Nucleic Acids Res, 1996. 24(12): p. 2204–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marilley M, et al. , DNA structural variation affects complex formation and promoter melting in ribosomal RNA transcription. Mol Genet Genomics, 2002. 267(6): p. 781–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smircich P, Duhagon MA, and Garat B, Conserved Curvature of RNA Polymerase I Core Promoter Beyond rRNA Genes: The Case of the Tritryps. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics, 2015. 13(6): p. 355–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roux-Rouquie M and Marilley M, Modeling of DNA local parameters predicts encrypted architectural motifs in Xenopus laevis ribosomal gene promoter. Nucleic Acids Res, 2000. 28(18): p. 3433–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kownin P, Bateman E, and Paule MR, Eukaryotic RNA polymerase I promoter binding is directed by protein contacts with transcription initiation factor and is DNA sequence-independent. Cell, 1987. 50(5): p. 693–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Geiss GK, Radebaugh CA, and Paule MR, The fundamental ribosomal RNA transcription initiation factor-IB (TIF-IB, SL1, factor D) binds to the rRNA core promoter primarily by minor groove contacts. J Biol Chem, 1997. 272(46): p. 29243–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Heffler MA, Walters RD, and Kugel JF, Using electrophoretic mobility shift assays to measure equilibrium dissociation constants: GAL4-p53 binding DNA as a model system. Biochem Mol Biol Educ, 2012. 40(6): p. 383–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vlahovicek K, Kajan L, and Pongor S, DNA analysis servers: plot.it, bend.it, model.it and IS. Nucleic Acids Res, 2003. 31(13): p. 3686–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Munteanu MG, et al. , Rod models of DNA: sequence-dependent anisotropic elastic modelling of local bending phenomena. Trends Biochem Sci, 1998. 23(9): p. 341–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gabrielian A, Simoncsits A, and Pongor S, Distribution of bending propensity in DNA sequences. FEBS Lett, 1996. 393(1): p. 124–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nemoto N, et al. , Random mutagenesis of yeast 25S rRNA identify bases critical for 60S subunit structural integrity and function. Translation (Austin), 2013. 1(2): p. e26402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wai HH, et al. , Complete deletion of yeast chromosomal rDNA repeats and integration of a new rDNA repeat: use of rDNA deletion strains for functional analysis of rDNA promoter elements in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res, 2000. 28(18): p. 3524–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thomas BJ and Rothstein R, Elevated recombination rates in transcriptionally active DNA. Cell, 1989. 56(4): p. 619–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vorlickova M and Kypr J, Conformational variability of poly(dA-dT).poly(dA-dT) and some other deoxyribonucleic acids includes a novel type of double helix. J Biomol Struct Dyn, 1985. 3(1): p. 67–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ramstein J and Leng M, Salt-dependent dynamic structure of poly(dG-dC) × poly(dG-dC). Nature, 1980. 288(5789): p. 413–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xuan JC and Weber IT, Crystal structure of a B-DNA dodecamer containing inosine, d(CGCIAATTCGCG), at 2.4 A resolution and its comparison with other B-DNA dodecamers. Nucleic Acids Res, 1992. 20(20): p. 5457–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Krepl M, et al. , Effect of guanine to inosine substitution on stability of canonical DNA and RNA duplexes: molecular dynamics thermodynamics integration study. J Phys Chem B, 2013. 117(6): p. 1872–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.White CM, et al. , Evaluation of the effectiveness of DNA-binding drugs to inhibit transcription using the c-fos serum response element as a target. Biochemistry, 2000. 39(40): p. 12262–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Latt SA and Wohlleb JC, Optical studies of the interaction of 33258 Hoechst with DNA, chromatin, and metaphase chromosomes. Chromosoma, 1975. 52(4): p. 297–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kim SK and Norden B, Methyl green. A DNA major-groove binding drug. FEBS Lett, 1993. 315(1): p. 61–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xie WQ and Rothblum LI, Domains of the rat rDNA promoter must be aligned stereospecifically. Mol Cell Biol, 1992. 12(3): p. 1266–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Drygin D, et al. , Targeting RNA polymerase I with an oral small molecule CX-5461 inhibits ribosomal RNA synthesis and solid tumor growth. Cancer Res, 2011. 71(4): p. 1418–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Haddach M, et al. , Discovery of CX-5461, the First Direct and Selective Inhibitor of RNA Polymerase I, for Cancer Therapeutics. ACS Med Chem Lett, 2012. 3(7): p. 602–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xu H, et al. , CX-5461 is a DNA G-quadruplex stabilizer with selective lethality in BRCA1/2 deficient tumours. Nat Commun, 2017. 8: p. 14432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Maizels N, Dynamic roles for G4 DNA in the biology of eukaryotic cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2006. 13(12): p. 1055–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pape LK, Windle JJ, and Sollner-Webb B, Half helical turn spacing changes convert a frog into a mouse rDNA promoter: a distant upstream domain determines the helix face of the initiation site. Genes Dev, 1990. 4(1): p. 52–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rohs R, et al. , Origins of specificity in protein-DNA recognition. Annu Rev Biochem, 2010. 79: p. 233–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bewley C, Gronenborn AM., Clore GM., Minor Groove-Binding Architectural Proteins: Structure, Function, and DNA Recognition. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct, 1998. 27: p. 105–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Harteis S and Schneider S, Making the bend: DNA tertiary structure and protein-DNA interactions. Int J Mol Sci, 2014. 15(7): p. 12335–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Radebaugh CA, et al. , TATA box-binding protein (TBP) is a constituent of the polymerase I-specific transcription initiation factor TIF-IB (SL1) bound to the rRNA promoter and shows differential sensitivity to TBP-directed reagents in polymerase I, II, and III transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol, 1994. 14(1): p. 597–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kim JL, Nikolov DB, and Burley SK, Co-crystal structure of TBP recognizing the minor groove of a TATA element. Nature, 1993. 365(6446): p. 520–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dervan PB and Edelson BS, Recognition of the DNA minor groove by pyrroleimidazole polyamides. Curr Opin Struct Biol, 2003. 13(3): p. 284–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tsihlis ND and Grove A, The Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNA polymerase III recruitment factor subunits Brf1 and Bdp1 impose a strict sequence preference for the downstream half of the TATA box. Nucleic Acids Res, 2006. 34(19): p. 5585–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tsai FT and Sigler PB, Structural basis of preinitiation complex assembly on human pol II promoters. Embo j, 2000. 19(1): p. 25–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Deng W and Roberts SG, A core promoter element downstream of the TATA box that is recognized by TFIIB. Genes Dev, 2005. 19(20): p. 2418–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kishimoto T, et al. , Presence of a limited number of essential nucleotides in the promoter region of mouse ribosomal RNA gene. Nucleic Acids Res, 1985. 13(10): p. 3515–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wilkinson JK and Sollner-Webb B, Transcription of Xenopus ribosomal RNA genes by RNA polymerase I in vitro. J Biol Chem, 1982. 257(23): p. 14375–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.