Abstract

Symptomatic myocarditis is classically featured by a flu-like prodrome, dyspnea on exertion, palpitations, substernal chest pain, and abnormal electrocardiogram (ECG). The clinical diagnosis has often been challenging due to its similarities to acute coronary syndrome. Our case involved a patient who presented with claudication of bilateral lower extremity and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in the inferior leads. On cardiac catheterization, nonobstructed coronary arteries with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 30% were demonstrated. His clinical presentation was consistent with suspected myocarditis, and he improved with immunosuppression. In addition, his thrombocytopenia and severe symptoms of peripheral neuropathy responded to both immunotherapy and anticoagulation. This case highlights the interplay between history taking, physical examination, and multimodal diagnostic imaging.

Keywords: cardiology, pulmonary critical care, myocarditis

Introduction

Myocarditis is an inflammatory disease of the myocardium secondary to acute injury and inflammation. Clinical presentation can range from fatigue to fulminant congestive heart failure.1 Although the definitive diagnosis is made based on pathological findings, patients are usually treated based on clinical presentation, ECG changes and elevated cardiac biomarkers.2 We present the case of a patient who presented with claudication of the lower extremities and acute STEMI.

Case Presentation

A 57-year-old-male with a history of hyperlipidemia and chronic tobacco use presented with bilateral foot pain associated with blue discoloration and coolness over 1 day. He denied trauma to lower extremities and acute back injury. However, he did report eating abnormal tasting prosciutto 2 days prior to his arrival and was concerned regarding salmonella infection as the particular manufacturer had issued a recall. After eating this, the patient developed fever, fatigue, abdominal discomfort with associated 5 episodes of nonbloody diarrhea. He had lost his appetite for 2 days as a result. Additionally, the patient recalled that he had been bitten by his domesticated dog on his left index finger 7 days prior to symptoms. The patient was not vaccinated for SARS-CoV-2 and asymptomatic. He worked as a manager of a restaurant.

The patient’s initial vital signs were within normal limits. He was afebrile, blood pressure 93/54 mm Hg, heart rate 85 beats/min, respiration 16 breaths/min, and saturation 98% on ambient air. Physical examination revealed regular heart rhythm, without jugular venous distention and clear breath sounds in all lung fields. There was a small left finger lesion with surrounding erythema and discoloration. His lower extremities were slightly cyanotic, had palpable pulses, and were extremely sensitive to touch.

Laboratory values were significant for white blood cell count 18.8 × 103/µL with neutrophilic bands of 40.8%. His hemoglobin was 17.1 gm/dL without helmet cells, and platelets were 72 × 103/µL. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were 28 mm/hr and 42 mg/dL, respectively.

Additional laboratory values included sodium 130 mmol/L, carbon dioxide 21 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 47 mg/dL, and creatinine 3.41 mg/dL. Aspartate transaminase 502 IU/L, alanine transaminase 257 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 136 IU/L, NT-Pro-B Natriuretic peptide 5846 pg/mL, troponin 26.2 ng/dL, creatine kinase 1246 IU/L, PT 12.4 seconds, INR 1.08, PTT 43 seconds, fibrinogen 380 mg/dL, and D-dimer greater than 128 mg/dL. The patient’s multiple nasopharyngeal swabs for SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test returned negative. Urinalysis was negative for infection. Interestingly, microbiology reported his initial blood culture as positive for gram-negative rods, but subsequently changed the results to no organisms shown.

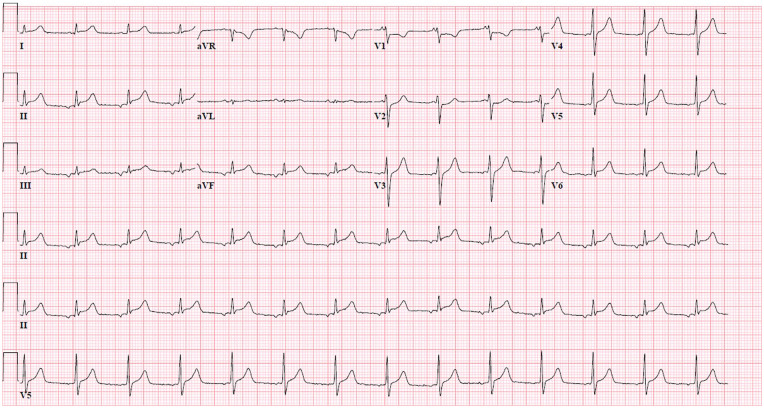

Initial ECG showed ST-segment elevation in the inferior leads (Figure 1), and his repeat ECG obtained 20 minutes after continued to show persistent inferior STEMI as well as borderline ST elevation in lead I. At this time, the patient started to endorse chest discomfort. Emergent cardiac catheterization revealed diffuse mild luminal irregularities with no focal stenosis or occlusion. His left ventricular end-diastolic pressure was noted to be elevated at 25 mm Hg. Subsequent to his arrival in the intensive care unit, transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed LVEF of 30% with diffuse hypokinesis and grade I diastolic dysfunction. He was supportive on low-dose norepinephrine a few hours after his diagnostic catheterization.

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram recorded at admission showed ST-segment elevation in the inferior wall leads II, III, and aVF.

Our patient then underwent computed tomography of chest and abdomen, which revealed bilateral peripheral septal thickening of the lungs with no evidence of pulmonary emboli or lymphadenopathy. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed a small acute punctate infarct of the left parietal lobe. His bilateral lower extremity arterial Doppler and ankle/brachial indices revealed no evidence of stenosis or occlusion.

We prescribed our patient intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone and heparin infusion for suspected clinical diagnosis of myocarditis, cefepime and doxycycline for sepsis, and gabapentin and morphine for neuropathic pain. Causes of myocarditis were thoroughly investigated. Autoimmune panel was negative for ANA, RNP, scleroderma, anti-Smith, and SSA/B antibodies. Stool cultures were negative for salmonella, shigella, campylobacter, and Escherichia coli 0157:H7. Serology for syphilis, Lyme, diphtheria, viral hepatitis, and parvovirus also returned negative. In our patient, positive results included IgG for mycoplasma pneumoniae, Epstein-Barr Virus capsid and nuclear antigen, toxoplasma, coxsackievirus, and influenza A and B.

Thirteen hours after admission, the patient’s troponin peaked at 119 ng/mL. His ECG at that time showed sinus rhythm with worsening ST elevation in leads I, aVL, II, III, aVF, and V4-6. By hospital day (HD) 2, renal function had recovered, yet his platelet count fell to nadir of 28 × 103/µL. He was evaluated for probable diagnosis of heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) by our hematologist. Extensive diagnostic workup did not yield any positive results. During this time, he developed bluish discoloration to the skin of the toes (Figure 2). He was empirically treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and argatroban, which resulted in platelet count recovery by HD 6. On the same day, the patient also had repeat TTE, which showed improved LVEF of 45%. Repeat ECG showed normalized ST-segments and incomplete right bundle branch block (RBBB) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Physical exam revealed acral areas of punctate erythema and blue discoloration on plantar surface and digits of feet.

Figure 3.

Review of the electrocardiogram on the sixth day of hospitalization demonstrated ST-segment normalization without Q waves in prior elevated leads I, aVL, II, III, aVF, and V4-6.

An incomplete right bundle branch block was present.

Discussion

Myocarditis is myocardial inflammation in response to acute injury resulting in necrosis and degeneration of myocytes.3 Endomyocardial biopsy is not often performed given the invasiveness of the procedure and the likelihood of sampling errors secondary to characteristic patchy inflammation.4,5 Therefore, most cases are diagnosed clinically while many remain subclinical due to nonspecific signs. On presentation, our patient reported lower extremity pain without cardiac discomfort. It is possible that his subtle cardiac signs and symptoms were overshadowed by the initial flu-like symptoms of fever, myalgias, and muscle tenderness, which were apparent prior to hospital admission. These symptoms could be attributable to myositis induced by a myotropic virus such as coxsackievirus A. An alternative explanation could have been his underlying gram-negative bacteremia resulted in disseminated intravascular coagulopathy that triggered an inflammatory cascade that ultimately injured the myocardium and peripheral nerves causing vasculitic neuropathy. His initial serum ESR and CRP further supported the above postulation.

Clinical myocarditis mimicking STEMI has an estimated clinical diagnostic incidence of 0.17 per 1000 man-years.6 The ST changes seen on ECG are likely due to pericardial involvement. In addition, cell membrane leakage and decrease in myocardial tissue oxygenation may also contribute to ST-segment elevation.7 Our patient underwent necessary cardiac catheterization to evaluate for occlusive coronary artery disease or spasm. This led us to consider diagnosis of clinical myocarditis in the setting of his presenting history. Our patient responded well to the treatment IV methylprednisolone, demonstrated improvement in his hemodynamic profile, ECG abnormalities, and TTE findings. His ECG on HD 6 showed an incomplete RBBB. Commonly, left bundle branch block and prolonged QRS duration have been associated with severe left ventricular dysfunction and sudden cardiac death.8

Given our patient’s initial platelet count of 72 × 103/µL, combined with leukocytosis and bandemia, sepsis was deemed the most likely cause of his initial thrombocytopenic state. His worsening platelet count led to the investigation of other probable causes, including HIT, ITP, HUS, and TTP. Although initial HIT antibody by enzyme-linked immunoassay was negative, there was concern for HIT due to the capillary (toes) and arterial (stroke) thromboses. His clinical symptoms and platelet counts responded to both IVIG and argatroban infusion, which suggested HIT as the more plausible diagnosis.

Conclusion

In conclusion, clinical myocarditis can be challenging to diagnose especially when patients present with atypical symptoms. ECG findings can mimic acute STEMI, and other findings can be constitutional and nonspecific. Patients may have multiple organ system involvement as a result of this systemic disease.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported (in whole or in part) by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA-Healthcare-affiliated entity. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA Healthcare or any of its affiliated entities.

Ethics Approval: Our institution did not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient(s) for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

ORCID iD: Blerina Asllanaj  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7640-6320

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7640-6320

References

- 1. Testani JM, Kolansky DM, Litt H, Gerstenfeld EP. Focal myocarditis mimicking acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction: diagnosis using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Tex Heart Inst J. 2006;33(2):256-259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wu S, Yang YM, Zhu J, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with myocarditis mimicking ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: analysis of a case series. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dec GW, Waldman H, Southern J, Fallon JT, Hutter AM, Palacios I. Viral myocarditis mimicking acute myocardial infarction. J AM Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:85-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chow LH, Radio SJ, Sears TD, McManus BM. Insensitivity of right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy in the diagnosis of myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;14:915-920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Angelini A, Calzolari V, Calabrese F, et al. Myocarditis mimicking acute myocardial infarction: role of endomyocardial biopsy in the differential diagnosis. Heart. 2000;84:245-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nozari Y, Tajdini M, Mehrani M, Ghaderpanah R. Focal myopericarditis as a rare but important differential diagnosis of myocardial infarction; a case series. Emerg (Tehran). 2016;4:159-162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen J, Chen S, Li Z, et al. Role of electrocardiograms in assessment of severity and analysis of the characteristics of ST elevation in acute myocarditis: a two-centre study. Exp Ther Med. 2020;20:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morgera T, Di Lenarda A, Dreas L, et al. Electrocardiography of myocarditis revisited: clinical and prognostic significance of electrocardiographic changes. Am Heart J. 1992;124:455-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]