Abstract

Capnocytophaga canimorsus (C. canimorsus) is an emerging pathogen in critical care. C. canimorsus is a Gram-negative bacillus, commonly isolated as a commensal microorganism of the oral flora of healthy dogs and cats. A 63-year-old woman came to the emergency department with fever, chills, and malaise 2 days after a minor dog bite. After admission to the medicine ward, she developed respiratory failure and livedo reticularis. In the intensive care unit (ICU), she presented full-blown septic shock with thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, severe acute kidney injury, and liver injury. We describe the first case of septic shock with Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome related to Capnocytophaga canimorsus infection in Sardinia and its treatment in a tertiary hospital ICU. We also review recent literature on the relevance of C. canimorsus in human disease and critical illness.

Keywords: Capnocytophaga, septic shock, acute kidney injury, renal replacement therapy, Zoonosis, case report, ischemia

Introduction

In 1976 Bobo and Newton published a case report describing the isolation of a new Gram-negative bacillus in a cerebrospinal fluid sample from a man who developed meningitis and sepsis after bites of dogs.1 A subsequent report of 17 cases confirmed the causative role of this Gram-negative rod in human disease.2 Due to its slow growth, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classified it in group DF-2 as a “dysgonic fermenter.” In 1989 Brenner et al. proposed to reclassify the DF-2 group as a new species called Capnocytophaga canimorsus.3 This suggestive name refers to the specific requirement of a carbon dioxide-enriched environment for growth and its main way of transmission in human disease, that is, dog bite.3

After these case reports, Capnocytophaga canimorsus has been recognized as an uncommon but increasingly significant pathogen associated with severe sepsis and septic shock.

We present the first case of septic shock related to Capnocytophaga canimorsus in Sardinia and its management in a tertiary hospital intensive care unit (ICU) and review the recent literature on the pathogenesis and critical illness caused by C. canimorsus.

Case report

A 63-year-old woman came to the emergency department with a chief complaint of acute onset fever (tympanic temperature 39.9°C) with chills and malaise. She was beclouded and tachypnoeic. Her history was notable for cigarette smoking and a previous breast cancer resection.

She suffered a recent dog hand bite 2 days before presentation. Laboratory values at arrival showed: creatinine 1.22 mg/dl, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 298, AST 115, ALT 54 U/l, hyponatremia 130 mmol/l, hyposmolality 265 mOsm/kg, PaO2/FiO2 ratio (P/F) 246 mmHg. Computerized tomography showed bilateral basal hyperdensities of the lungs. Two sets of peripheral blood were collected for microbiological diagnosis.

She was admitted to the medicine department with a diagnosis of pneumonia and began empirical antibiotic therapy with levofloxacin (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score, SOFA 5).

The following day, she developed thrombocytopenia, acute kidney injury (AKI), livedo reticularis, arterial hypotension, and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure with high serum procalcitonin (79.7 ng/ml). The Gram staining of the blood culture showed thin and slender Gram-negative rods, so she started an empirical course of meropenem (Figure 1). The patient was admitted to the ICU and intubated. Her condition rapidly worsened to full-blown septic shock (SOFA 21) with severe lactic acidosis (pH 6.7, lactate 17 mmol/l). She required high-dose inotropic support (norepinephrine 0.5–1 μg/kg/min) and continuous mandatory mechanical ventilation (P/F 90). She was also administered hydrocortisone 200 mg/die. Her AKI stage was 3 according to Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes classification due to anuria and a serum creatinine of 3.91 mg/dl, so she underwent renal replacement therapy using continuous venovenous hemodialysis (CVVHD) with a high cutoff and high flux hemofilter (Ultraflux EMiC2, Fresenius, Germany) under citrate anticoagulation. After 72 h, this strategy improved hemodynamics, gas exchange, and level of consciousness.

Figure 1.

Direct Gram stain of blood culture. This picture shows the Gram-negative slender rods isolated from our patient culture bottle.

On the fourth day of ICU stay, she developed rhabdomyolysis and liver injury (Figure 2). Severe thrombocytopenia (Figure 2) and coagulopathy required fresh frozen plasma and platelet transfusion under thromboelastographic guidance. Livedo reticularis worsened to a frank purpura, with ischemia of the limbs (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Main laboratory findings during ICU stay. This picture shows six plots that illustrate serum creatinine (panel A), serum alanine aminotransferase (panel B), blood urea nitrogen (panel C), platelets count (panel D), serum creatine phosphokinase (panel E), seru m procalcitonin (panel F) on the y axis and the day of ICU stay on the x-axis.

Abbreviations: ICU: Intensive Care Unit; mg: milligram; dl: deciliter; U: international units; L: liter; ng: nanograms.

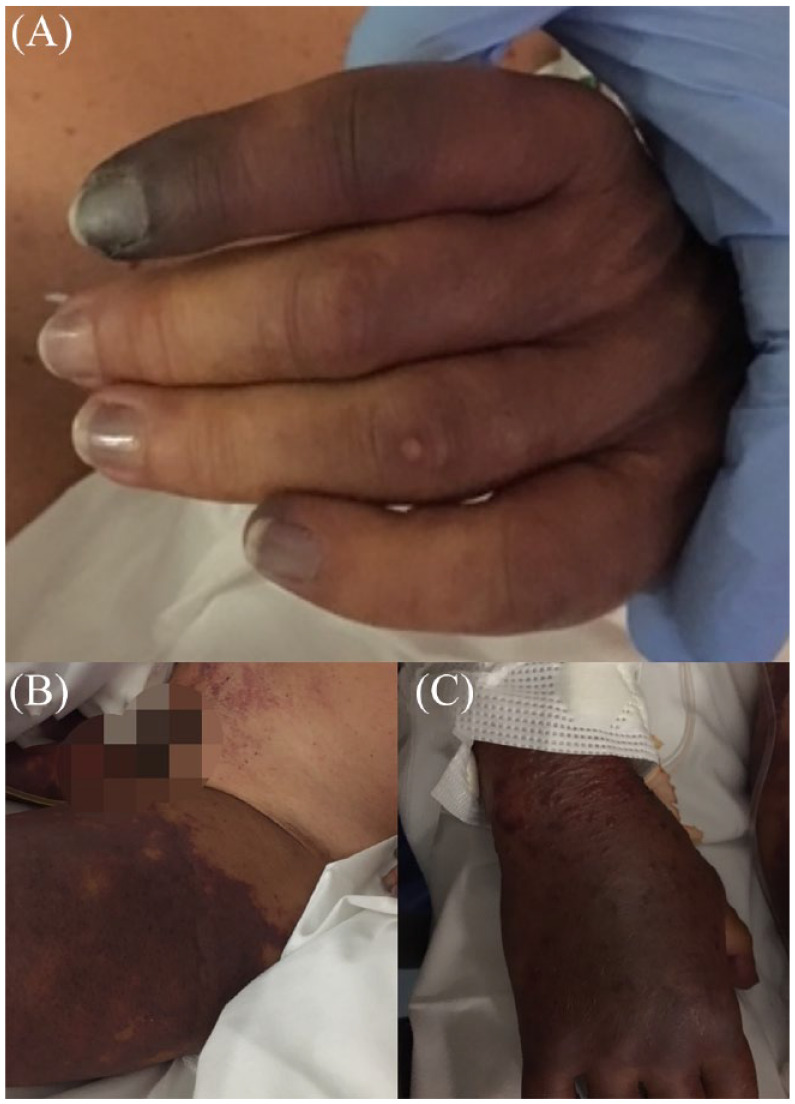

Figure 3.

Physical findings. This picture shows the purpuric skin lesions in different anatomic locations: left hand (panel A), thighs (panel B), right hand (panel C).

The microbiological diagnosis of this case began with the analysis of blood cultures using the automated BacT / ALERT system (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France).

A sample of blood was then plated on blood agar and chocolate agar. After 1 week, the culture became positive. A sample from a direct smear of bacterial colonies was then analyzed by the MALDI Biotyper (Bruker, Germany). The MALDI biotyper provided a specific proteomic spectrum fingerprint for C. canimorsus. On the seventh day, she started ampicillin-sulbactam and ceftriaxone. After the resolution of the critical illness, we received the antibiogram. The isolated strain was sensitive to amoxicillin with clavulanic acid, ticarcillin with clavulanic acid, piperacillin, imipenem, cefoxitin, moxifloxacin, rifampin, chloramphenicol, while it was resistant to penicillin G, amoxicillin, clindamycin, vancomycin, metronidazole.

After 2 weeks of stay in the ICU, she was transferred to a facility near her hometown, where she underwent surgical amputation of her finger in the hand, ie, the site of the dog bite, and both inferior limbs below the knees. Eight months after her critical illness, she still required intermittent hemodialysis for end-stage renal disease.

The microbiological diagnosis of this case began with the analysis of blood cultures using the automated BacT/ALERT system (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France).

A sample of blood was then plated on blood agar and chocolate agar. After 1 week, the culture became positive. A sample from a direct smear of bacterial colonies was then analyzed by the MALDI Biotyper (Bruker, Germany). The MALDI Biotyper provided a specific proteomic spectrum fingerprint for C. canimorsus.

Review of the literature

We searched the MEDLINE® database using the medical subject headings term Capnocytophaga to retrieve pertinent studies on the microbiology, pathogenesis, and clinical manifestation of C. canimorsus in human patients. We did not enforce any language restriction. The genus Capnocytophaga was originally isolated from the human oral cavity and is made of Gram-negative, nonflagellated, fermentative, and capnophilic bacteria (5%–10% of carbon dioxide in growth medium) that exhibit glide motility. C. canimorsus appear as long, thin, filamentous, spindle-shaped cells in blood Agar plates.3

It is a common commensal species of the oral flora of dogs and cats and can be isolated in 21%–73% of oropharyngeal swabs from dogs.4,5

C. canimorsus feeds on N-acetyl glucosamine and N-acetyl galactosamine from host cell glycoproteins (epithelial and macrophage cells), and the presence of macrophages increases bacterial growth.6 –8 The same surface N-glycan glycoprotein deglycosylation complex can also deglycosilate human immunoglobulin G (IgG) and modify the affinity of IgG for its Fc receptor.8,9

C. canimorsus can also prevent effective secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as nitric oxide, IL-1 α, IL-6, or TNFα, maybe through active production of a factor capable of complete dephosphorylation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and a peculiar lipopolysaccharide structure.8,10

Evidence of resistance to phagocytic killing and feeding on macrophage glycoproteins may represent an essential factor not only for commensalism, but also for pathogenesis.6,8

Host factors can determine the vulnerability to C. canimorsus infection, such as asplenia, hyposplenism, alcohol abuse, and malignancy, supported by the disproportionately low incidence of C. canimorsus sepsis despite widespread exposure to dog or cat saliva in the general population.11

Butler’s comprehensive review included all microbiologically confirmed cases of C. canimorsus infection and an estimated 484 clinical cases with a lethality rate of 26%.11

The same review listed 30 cases of septic shock and 18 cases of digital or limb gangrene in the period.11

In Supplemental Table and Figure 4 we summarized (1990–2022, up to April 25, 2022) case reports and case series describing C. canimorsus infection in human patients, with a focus on clinical course, outcome, organ failure, risk factors for C. canimorsus infection (i.e. bites, scratching, or close contacts with dogs or cats), immunosuppressed status (i.e. alcohol abuse, asplenia, corticosteroid therapy, methotrexate, immunosuppression malignancy).

Figure 4.

Bar chart of organ failures described in published case reports and series. This graph shows how many papers described each type of organ injury or failure.

In the period 1990–2022, 125 articles described 207 cases of C. canimorsus infection (Supplemental Table).12 –137

Forty-seven studies described 73 cases of severe sepsis or septic shock, with 31% case fatality (see Supplemental Table). Despite the importance of risk factors for the development of severe C. canimorsus infection, 33 patients were not immunocompromised.

Treatment of organ failures was not always described in detail in case reports, probably for editorial reasons and also because some patients died briefly after the first clinical manifestations of infection.57,63,78,90,91

Furthermore, septic shock from C. canimorsus does not appear to require other specific treatments than those reported in current septic shock guidelines.

The most severe cases showed a high prevalence of acute kidney injury (60 reports). Renal replacement therapy was the most described therapy.52,55,67,70,80,89

Feige et al. reported the use of renal replacement therapy with regional anticoagulation, to manage the rapid development of severe AKI with significant metabolic derangement, hemodynamic instability, and coagulopathy.89

Coagulopathy is common in the setting of severe sepsis or septic shock of C. canimorsus (67 reports).

Furthermore, two case reports described the atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and the Shwartzman reaction related to septic shock of C. canimorsus with their specific treatments, eculizumab (humanized monoclonal IgG anti-C5), and nebacumab (antilipid A IgG), respectively.55,80

Irreversible limb or digit ischemia was described in association with severe sepsis or septic shock (22 reports), suggesting significant microcirculation injury as one of the main pathophysiological mechanisms of systemic C. canimorsus infection.

We suppose that the published literature provided an underestimation of the relevance of this pathogen, due to its difficult microbiological diagnosis and fulminant course in the most severe cases, which can misleadingly suggest a more common etiologic agent, such as Neisseria meningitidis. The published literature offers some descriptions of purulent cases of meningitis caused by C. canimorsus, whose identification was possible by broad-range polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or 16S ribosomal RNA amplification from blood and CSF samples72,128,138

Capnocytophaga canimorsus is a rare cause of endocarditis and it is particularly rare in immunocompetent hosts.85,92,122 These cases of endocarditis share a common factor: the difficult process of microorganism isolation that occurred after many blood cultures or after PCR analysis of valvular tissue.

C. canimorsus infection can cause direct macrovascular damage, including single or multiple mycotic aneurysms.69,109,124,139 These aneurysms may present with rupture and hemodynamic instability or have a quite indolent course, resolving after surgical, and antibiotic treatment.

C. canimorsus infection may also display nonspecific skin changes, such as multiple erythematous macules, erythema annulare centrifugum, or urticaria.111,127

C. canimorsus has also been isolated in conjunction with Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection.110,126

These case studies are important reminders to consider co-infection or super-infection by less common pathogens in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19). Furthermore, in the pandemic era, the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection is straightforward and has important consequences, such as that it may prompt significant changes in allocation and management, such as isolation wards and immunomodulatory therapies.

In this setting, the diagnosis of Covid-19 may overshadow rarer infections, including C. canimorsus.

As a confirmation of this, a case of C- canimorsus fulminant septic shock in a SARS-CoV-2 positive patient was diagnosed postmortem.126

Conclusions

The case we presented is the first description of a septic shock with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome in an immunocompetent patient caused by C. canimorsus in Sardinia.

According to the data presented, both healthy and immunosuppressed hosts can rapidly develop a severe septic syndrome characterized by a high incidence of AKI, coagulopathy, and cardiovascular instability. C. canimorsus infection should always be suspected in the differential diagnosis of Gram-negative sepsis, and risk factors, such as immunocompromised status and exposure to pets, should not be overlooked. Despite the absence of a specific therapy or the limited relevance of antibiotic resistance in C. canimorsus, the clinical suspect of this infection must induce to treat aggressively in the ICU due to its rapid course. According to our experience and the published literature, the most alarming signs, such as purpura, rapid worsening of respiratory and renal failure, should be interpreted as the clinical manifestation of systemic microvascular damage due to C. canimorsus.

No other case report described the use of a high cutoff filter in septic shock from C. canimorsus, but in our experience, it could be the best option to address AKI and the accumulation of myoglobin, cytokines, and interleukins.140,141 Considering the frequent occurrence of severe coagulopathy, we suggest early placement of a large-bore hemodialysis catheter in a compressible site.

Furthermore, we believe that a more widespread adoption of antibiotic prophylaxis after high-risk bite injuries could contribute significantly to reducing the incidence of C. canimorsus infection.

Our case report and review of the literature confirm the role of Capnocytophaga canimorsus as an emerging cause of septic shock and multiorgan failure. Our article aims to add a little piece to the enormous amount of collective experience on this increasingly important pathogen and to raise awareness of this uncommon species among intensivists. Given the proteiform manifestations of Capnocytophaga canimorsus, as demonstrated by the published literature, this pathogen should be on the differential diagnosis list of every clinician, even during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. This experience was so important to our group that we correctly identified a second case the following year, which resulted in an early diagnosis (data are not presented because we did not obtain patient consent to add this case to our report). Our take-home messages for intensivists are always suspect C. canimorsus in rapidly evolving sepsis/septic shock, proactively investigate its presence, and consider early renal replacement therapy, especially in those patients who show clinical signs of microvascular damage.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-phj-10.1177_22799036221133234 for The Great pretender: the first case of septic shock due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus in Sardinia. A Case report and review of the literature by Salvatore Sardo, Claudia Pes, Andrea Corona, Giulia Laconi, Claudia Crociani, Pietro Caddori, Maria Luisa Boi and Gabriele Finco in Journal of Public Health Research

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: SS, designed the study, collected and managed the review data, wrote the original draft, reviewed and edited; CP, collected the review data, wrote the original draft, reviewed and edited; AC, collected the review data, wrote the original draft, reviewed and edited; GL, collected the review data, reviewed and edited; CC, reviewed and edited; PC, reviewed and edited; MLB reviewed and edited; GF, reviewed and edited.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: The authors declare that approval from a Human Research Ethics Committee was not required for this study. The patient and her relatives gave their consent to the publication of this case report. The authors sent them the manuscript draft and images to receive explicit approval before submission.

Significance for public health section: Capnocytophaga canimorsus is a rare cause of rapidly progressive septic shock with a significant derangement of the function of the main organs and tissue ischemia due to microcirculation obstruction. As this microorganism eludes traditional microbiologic investigations, it is of paramount importance to include this species in the differential diagnosis of overwhelming septic shock and meningitis, especially in patients with close contact with dogs and cats. The presentation of C. canimorsus septic shock might be easily confused with meningococcal septic shock. The case described in this report served as an important reminder to accelerate the correct diagnosis in a subsequent case of C. canimorsus shock admitted the following year to the same intensive care unit (case not described because the patient did not give consent).

ORCID iD: Salvatore Sardo  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7664-8928

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7664-8928

References

- 1. Bobo RA, Newton EJ. A previously undescribed gram-negative bacillus causing septicemia and meningitis. Am J Clin Pathol 1976; 65: 564–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Butler T, Weaver RE, Ramani TK, et al. Unidentified gram-negative rod infection. A new disease of man. Ann Intern Med 1977; 86(1): 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brenner DJ, Hollis DG, Fanning GR, et al. , . Capnocytophaga canimorsus sp. nov. (formerly CDC group DF-2), a cause of septicemia following dog bite, and C. cynodegmi sp. nov., A cause of localized wound infection following dog bite. J Clin Microbiol 1989; 27: 231–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dilegge SK, Edgcomb VP, Leadbetter ER. Presence of the oral bacterium Capnocytophaga canimorsus in the tooth plaque of canines. Vet Microbiol 2011; 149: 437–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Dam AP, van Weert A, Harmanus C, et al. Molecular characterization of Capnocytophaga canimorsus and other canine Capnocytophaga spp. and assessment by PCR of their frequencies in dogs. J Clin Microbiol 2009; 47: 3218–3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mally M, Shin H, Paroz C, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus: a human pathogen feeding at the surface of epithelial cells and phagocytes. PLoS Pathog 2008; 4: e1000164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Manfredi P, Renzi F, Mally M, et al. The genome and surface proteome of Capnocytophaga canimorsus reveal a key role of glycan foraging systems in host glycoproteins deglycosylation. Mol Microbiol 2011; 81: 1050–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shin H, Mally M, Kuhn M, et al. Escape from immune surveillance by Capnocytophaga canimorsus. J Infect Dis 2007; 195: 375–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ittig S, Lindner B, Stenta M, et al. The lipopolysaccharide from capnocytophaga canimorsus reveals an unexpected role of the core-oligosaccharide in MD-2 binding. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8: e1002667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zähringer U, Ittig S, Lindner B, et al. NMR-based structural analysis of the complete rough-type lipopolysaccharide isolated from Capnocytophaga canimorsus. J Biol Chem 2015; 290: 25273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Butler T. Capnocytophaga canimorsus: an emerging cause of sepsis, meningitis, and post-splenectomy infection after dog bites. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2015; 34: 1271–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hantson P, Gautier PE, Vekemans MC, et al. Fatal Capnocytophaga canimorsus septicemia in a previously healthy woman. Ann Emerg Med 1991; 20: 93–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scarlett JD, Williamson HG, Dadson PJ, et al. A syndrome resembling thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura associated with Capnocytophaga canimorsus septicemia. Am J Med 1991; 90: 127–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Howell JM, Woodward GR. Precipitous hypotension in the emergency department caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus sp nov sepsis. Am J Emerg Med 1990; 8: 312–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Evans RJ. DF2 septicaemia. J R Soc Med 1991; 84: 749–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bateman JM, Rainford DJ, Masterton RG. Capnocytophaga canimorus infection and acute renal failure. J Infect 1992; 25: 112–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Malnick H, Adhami ZN, Galloway A. Isolation and identification of Capnocytophaga canimorsus (DF-2) from blood culture. Lancet Lond Engl 1991; 338: 384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gallen IW, Ispahani P. Fulminant Capnocytophaga canimorsus (DF-2) septicaemia. Lancet Lond Engl 1991; 337: 308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kullberg BJ, Westendorp RG, van’t Wout JW, et al. Purpura fulminans and symmetrical peripheral gangrene caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus (formerly DF-2) septicemia—a complication of dog bite. Medicine 1991; 70: 287–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ndon JA. Capnocytophaga canimorsus septicemia caused by a dog bite in a hairy cell leukemia patient. J Clin Microbiol 1992; 30: 211–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pletschette M, Köhl J, Kuipers J, et al. Opportunistic Capnocytophaga canimorsus infection. Lancet Lond Engl 1992; 339: 308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Decoster H, Snoeck J, Pattyn S. Capnocytophaga canimorsus endocarditis. Eur Heart J 1992; 13: 140–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Blanchard G, Boulet E, Martres P, et al. Infections à capnocytophaga canimorsus : à propos de trois cas. Médecine Mal Infect 1996; 26: 596–598. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mirza I, Wolk J, Toth L, et al. Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome secondary to Capnocytophaga canimorsus septicemia and demonstration of bacteremia by peripheral blood smear. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000; 124: 859–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rintala E, Kauppila M, Seppälä OP, et al. Protein C substitution in sepsis-associated purpura fulminans. Crit Care Med 2000; 28: 2373–2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yu RK, Shepherd LE, Rapson DA. Capnocytophaga canimorsus, a potential emerging microorganism in splenectomized patients. Br J Haematol 2000; 109: 679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mulder AH, Gerlag PG, Verhoef LH, et al. Hemolytic uremic syndrome after capnocytophaga canimorsus (DF-2) septicemia. Clin Nephrol 2001; 55: 167–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chodosh J. Cat’s tooth keratitis: human corneal infection with Capnocytophaga canimorsus. Cornea 2001; 20: 661–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Papadaki TG, Moussaoui RE, van Ketel RJ, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus endogenous endophthalmitis in an immunocompetent host. Br J Ophthalmol 2008; 92: 1566–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Macrea MM, McNamee M, Martin TJ. Acute onset of fever, chills, and lethargy in a 36-year-old woman. Chest 2008; 133: 1505–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Coutance G, Labombarda F, Pellissier A, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus endocarditis with root abscess in a patient with a bicuspid aortic valve. Heart Int 2009; 4: e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hayani O, Higginson LA, Toye B, et al. Man’s best friend? Infective endocarditis due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus. Can J Cardiol 2009; 25: e130–e132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rossi P, Oger A, Bagneres D, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus septicaemia in an asplenic patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. BMJ Case Rep 2009; 2009: bcr0520091840–bcr0520091840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Handrick W, Schwede I, Steffens U. [Fatal sepsis due to capnocytophaga canimorsus after dog bite]. Med Klin Munich Ger 2010; 105: 739–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eefting M, Paardenkooper T. Capnocytophaga canimorsus sepsis. Blood 2010; 116: 1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stiegler D, Gilbert JD, Warner MS, et al. Fatal dog bite in the absence of significant trauma: Capnocytophaga canimorsus infection and unexpected death. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2010; 31: 198–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kourelis T, Kannan S, Foley RJ. An unusual case of septic shock in a geriatric patient. Conn Med 2010; 74: 133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Joshi M, Reddy S, Ryan C, et al. Septicemia due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus following dog bite in an elderly male. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2011; 54: 368–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. O’Rourke GA, Rothwell R. Capnocytophaga canimorsis a cause of septicaemia following a dog bite: a case review. Aust Crit Care 2011; 24: 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hawkins J, Wilson A, McWilliams E. ‘Biting the hand that feeds’: fever and altered sensorium following a dog bite. BMJ Case Rep 2011; 2011. DOI: 10.1136/bcr.08.2010.3265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Band RA, Gaieski DF, Goyal M, et al. A 52-year-old man with malaise and a petechial rash. J Emerg Med 2011; 41: 39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Brichacek M, Blake P, Kao R. Capnocytophaga canimorsus infection presenting with complete splenic infarction and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: a case report. BMC Res Notes 2012; 5: 695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ganguli I, Pierce C, Sharpe B, et al. The hand that feeds you. J Hosp Med 2012; 7: 590–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Christiansen CB, Berg RM, Plovsing RR, et al. Two cases of infectious purpura fulminans and septic shock caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus transmitted from dogs. Scand J Infect Dis 2012; 44: 635–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Matulionytė R, Lisauskienė I, Kėkštas G, et al. Two dog-related infections leading to death: overwhelming Capnocytophaga canimorsus sepsis in a patient with cystic echinococcosis. Med Kaunas Lith 2012; 48: 11–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sacks R, Kerr K. A 42-year-old woman with septic shock: an unexpected source. J Emerg Med 2012; 42: 275–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Popiel KY, Vinh DC. ‘Bobo-Newton syndrome’: an unwanted gift from man’s best friend. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol J Can Mal Infect Microbiol Medicale 2013; 24: 209–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rougemont M, Ratib O, Wintsch J, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus prosthetic aortitis in an HIV-positive woman. J Clin Microbiol 2013; 51: 2769–2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yamamoto U, Kunita M, Mohri M. Shock following a cat scratch. BMJ Case Rep 2013. DOI: 10.1136/bcr-2012-007892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ma A, Goetz MB. Capnocytophaga canimorsus sepsis with associated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Med Sci 2013; 345: 78–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fent GJ, Kamaruddin H, Garg P, et al. Hypertensive emergency and type 2 myocardial infarction resulting from pheochromocytoma and concurrent capnocytophaga canimorsus infection. Open Cardiovasc Med J 2014; 8: 43–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hloch O, Mokra D, Masopust J, et al. Antibiotic treatment following a dog bite in an immunocompromized patient in order to prevent Capnocytophaga canimorsus infection: a case report. BMC Res Notes 2014; 7: 432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tuuminen T, Viiri H, Vuorinen S. The Capnocytophaga canimorsus isolate that caused sepsis in an immunosufficient man was transmitted by the large pine weevil Hylobius abietis. J Clin Microbiol 2014; 52: 2716–2717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shahani L, Khardori N. Overwhelming Capnocytophaga canimorsus infection in a patient with asplenia. BMJ Case Rep 2014; 2014: bcr2013202768. DOI: 10.1136/bcr-2013-202768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tan V, Schwartz JC. Renal failure due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus generalized Shwartzman reaction from a dog bite (DF-2 nephropathy). Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent 2014; 27: 139–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chiappa V, Chang CY, Sellas MI, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 10-2014. A 45-year-old man with a rash. New Engl J Med 2014; 370: 1238–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bastida MT, Valverde M, Smithson A, et al. [Fulminant sepsis due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus: diagnosis by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry]. Med Clin 2014; 142: 230–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ugai T, Sugihara H, Nishida Y, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus sepsis following BMT in a patient with AML: possible association with functional asplenia. Bone Marrow Transplant 2014; 49: 153–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sotiriou A, Sventzouri S, Nepka M, et al. Acute generalized livedo racemosa caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus identified by MALDI-TOF MS. Int J Infect Dis IJID 2015; 33: 196–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Cooper JD, Dorion RP, Smith JL. A rare case of Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus in an immunocompetent patient. Infection 2015; 43: 599–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Nishioka H, Kozuki T, Kamei H. Capnocytophaga canimorsus bacteremia presenting with acute cholecystitis after a dog bite. J Infect Chemother 2015; 21: 215–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Joswig H, Gers B, Dollenmaier G, et al. A case of Capnocytophaga canimorsus sacral abscess in an immunocompetent patient. Infection 2015; 43: 217–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kovalev DV, Putintsev VA, Bogomolov DV, et al. [Postmortem forensic medical diagnostics of fulminant sepsis caused by Gram-negative bacterium (Capnocitophaga canimorsus) following a dog bite]. Sud Med Ekspert 2015; 58: 49–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Dobosz P, Martyna D, Stefaniuk E, et al. [Severe sepsis after dog bite caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus]. Pol Merkur Lek Organ Pol Tow Lek 2015; 39: 219–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wilson JP, Kafetz K, Fink D. Lick of death: Capnocytophaga canimorsus is an important cause of sepsis in the elderly. BMJ Case Rep 2016; 2016. DOI: 10.1136/bcr-2016-215450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hästbacka J, Hynninen M, Kolho E. Capnocytophaga canimorsus bacteremia: clinical features and outcomes from a Helsinki ICU cohort. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2016; 60: 1437–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Maezawa S, Kudo D, Asanuma K, et al. Severe sepsis caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsuscomplicated by thrombotic microangiopathy in an immunocompetent patient. Acute Med Surg 2017; 4: 97–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Jordan CS, Miniter U, Yarbrough K, et al. Urticarial exanthem associated with Capnocytophaga canimorsus bacteremia after a dog bite. JAAD Case Rep 2016; 2: 98–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Evans TJ, Lyons OT, Brown A, et al. Mycotic aneurysm following a dog bite: the value of the clinical history and Molecular Diagnostics. Ann Vasc Surg 2016; 32: 130.e5–130.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Dedy NJ, Coghill S, Chandrashekar NKS, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus sepsis following a minor dog bite to the Finger: case report. J Hand Surg 2016; 41: 81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. van Samkar A, Brouwer MC, Schultsz C, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsusMeningitis: three cases and a review of the literature. Zoonoses Public Health 2016; 63: 442–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Beernink TM, Wever PC, Hermans MH, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus meningitis diagnosed by 16S rRNA PCR. Pract Neurol 2016; 16: 136–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Thommen F, Opota O, Greub G, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus endophthalmitis after cataract surgery linked to salivary dog-to-human transmission. Retin Cases Brief Rep 2020; 14: 183–186. DOI: 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Tamura S, Koyama A, Yamashita Y, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus sepsis in a methotrexate-treated patient with rheumatoid arthritis. IDCases 2017; 10: 18–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Morandi EM, Pauzenberger R, Tasch C, et al. A small ‘lick’ will sink a great ship: fulminant septicaemia after dog saliva wound treatment in an asplenic patient. Int Wound J 2017; 14: 1025–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Orth M, Orth P, Anagnostakos K. Capnocytophaga canimorsus – An underestimated cause of periprosthetic joint infection? Knee 2017; 24: 876–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Brunet J, Lhermitte D, Seguin A, et al. [Capnocytophaga canimorsus: A cause of multi-organ failure accompanied by livedo]. Med Mal Infect 2017; 47: 370–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Taquin H, Roussel C, Roudière L, et al. Fatal infection caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17: 236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Beltramone M, Moreau N, Martinez-Almoyna L. Capnocytophaga canimorsus, a rare cause of bacterial meningitis. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2017; 173: 74–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Sokol KA, Veluswamy RR, Zimmerman BS, et al. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with Capnocytophaga canimorsus. Am J Hematol 2017; 92: 322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. El-Battrawy I, Ansari U, Behnes M, et al. Dyspnoe und Hautausschlag bei einem 49-jährigen Patienten. Internist 2017; 58: 282–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Salvisberg C, Bartkowicki W, Imschweiler T, et al. Knieprotheseninfekt mit Capnocytophaga canimorsus: Prothesenerhalt oder -wechsel? Praxis 2017; 106: 483–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Marmo M, Villani R, Di Minno RM, et al. Cave canem: HBO2 therapy efficacy on Capnocytophaga canimorsus infections: a case series. Undersea Hyperb Med J Undersea Hyperb Med Soc Inc 2017; 44: 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Taki M, Shimojima Y, Nogami A, et al. Sepsis caused by newly identified Capnocytophaga canis following cat bites: C. canis is the third candidate along with C. canimorsus and C. cynodegmi causing zoonotic infection. Intern Med Tokyo Jpn 2018; 57: 273–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Barry M. Double native valve infective endocarditis due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus: first reported case caused by a Lion Bite. Case Rep Infect Dis 2018; 2018: 4821939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Bertin N, Brosolo G, Pistola F, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus: an emerging pathogen in immunocompetent patients-experience from an emergency department. J Emerg Med 2018; 54: 871–875. DOI: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.01.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Hettiarachchi I, Parker S, Singh S. ‘barely a scratch’: Capnocytophaga canimorsus causing prosthetic hip joint infection following a dog scratch. BMJ Case Rep 2018; 2018: bcr-2017–221185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Abreu-Salinas F, Castelló-Abietar C, Ameijide Sanluis E, et al. [Capnocytophaga canimorsus as a cause of sepsis and meningitis in immunosuppressed patient]. Rev Espanola Quimioter Publicacion 2018; 31: 70–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Feige K, Hartmann P, Lutz JT. [Fulminant sepsis after Capnocytophaga canimorsus infection]. Anaesthesist 2018; 67: 34–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Piccinelli G, Caccuri F, De Peri E, et al. Fulminant septic shock caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus in Italy: case report. Int J Infect Dis 2018; 72: 3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Vignon G, Combeau P, Violette J, et al. [A fatal septic shock due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus and review of literature]. Rev Med Interne 2018; 39: 820–823. DOI: 10.1016/j.revmed.2018.03.384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Jalava-Karvinen P, Grönroos JO, Tuunanen H, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus: a rare case of conservatively treated prosthetic valve endocarditis. APMIS Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand 2018; 126: 453–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Elliott J, Donaldson E. Acute cholecystitis secondary to dog bite. Int J Surg Case Rep 2019; 55: 230–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Tsutsumi R, Yoshida Y, Suzuki M, et al. Image Gallery: annular erythema related to Capnocytophaga canimorsus bacteraemia after a dog bite. Br J Dermatol 2018; 179: e196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Mantovani E, Busani S, Biagioni E, et al. Purpura fulminans and septic shock due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus after Dog Bite: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Crit Care 2018; 2018: 7090268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Smeets NJL, Fijnheer R, Sebastian S, et al. Secondary thrombotic microangiopathy with severely reduced ADAMTS13 activity in a patient with Capnocytophaga canimorsus sepsis: a case report. Transfusion 2018; 58: 2426–2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Cabrol M, Le Bars H, Bailly P, et al. [Capnocytophaga canimorsus bacterial meningitis]. Med Mal Infect 2018; 48: 419–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Cardoso RM, Rodrigues J, Garcia D, et al. Tricuspid valve endocarditis due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus. BMJ Case Rep 2019; 12: e233721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Hopkins AM, Desravines N, Stringer EM, et al. Capnocytophaga bacteremia precipitating severe thrombocytopenia and preterm labor in an asplenic host. Infect Dis Rep 2019; 11: 8272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Mader N, Lührs F, Herget-Rosenthal S, et al. Being Licked by a dog can Be fatal: capnocytophaga canimorsus sepsis with Purpura Fulminans in an immunocompetent man. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med 2019; 6: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Sakai J, Imanaka K, Kodana M, et al. Infective endocarditis caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus; a case report. BMC Infect Dis 2019; 19: 927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Sabia L, Marchesini D, Pignataro G, et al. Beware of the dog – capnocytophga canimorsus septic shock: a case report. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2019; 23: 7517–7518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Bialasiewicz S, Duarte TPS, Nguyen SH, et al. Rapid diagnosis of Capnocytophaga canimorsus septic shock in an immunocompetent individual using real-time nanopore sequencing: a case report. BMC Infect Dis 2019; 19: 660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Tani N, Nakamura K, Sumida K, et al. An immunocompetent case of Capnocytophaga canimorsus infection complicated by secondary thrombotic microangiopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Intern Med Tokyo Jpn 2019; 58: 3479–3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Hundertmark M, Williams T, Vogel A, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus as cause of Fatal sepsis. Case Rep Infect Dis 2019; 2019: 3537507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Tanabe K, Okamoto S, Hiramatsu Asano S, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus peritonitis diagnosed by mass spectrometry in a diabetic patient undergoing peritoneal dialysis: a case report. BMC Nephrol 2019; 20: 219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Kelly BC, Constantinescu DS, Foster W. Capnocytophaga canimorsus periprosthetic joint infection in an immunocompetent patient: a case report. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2019; 10: 2151459318825199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Ahmad S, Yousaf A, Inayat F, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus-associated sepsis presenting as acute abdomen: do we need to think outside the box? BMJ Case Rep 2019; 12: e228167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Barry I, Sieunarine K, Bond R. Ruptured mycotic common iliac aneurysm due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus, acquired from dog saliva: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2021; 78: 12–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Wendt R, Schauff C, Lübbert C. An asplenic with life-threatening Capnocytophaga canimorsus sepsis. IDCases 2020; 21: e00828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Klein C, Mahé A, Goussot R, et al. [Multiple erythema annulare centrif ugum associated with knee monoarthritis revealing capnocytophagacanimorsus infection]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2020; 147: 373–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Prasil P, Ryskova L, Plisek S, et al. A rare case of purulent meningitis caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus in the Czech Republic – case report and review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis 2020; 20: 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Ashley PA, Moreno DA, Yamashita SK. Capnocytophaga canimorsus aortitis in an immunocompetent host. Hawaii J Health Soc Welf 2020; 79: 324–325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Knabl L, Mango M, Stögermüller B, et al. Cluedo – source identification in a case of septicemia fatality caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2020; 24: 7151–7154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Mori J, Oshima K, Tanimoto T. Cat rearing: A potential risk of fulminant sepsis caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus in a hemodialysis patient. Case Rep Nephrol Dial 2020; 10: 51–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Woźniak P, Szymczak R, Piotrowska A. A case of fulminant sepsis caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus after a dog bite. IDCases 2020; 21: e00798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Bering J, Hartmann C, Asbury K, et al. Unexpected pathogen presenting with purulent meningitis. BMJ Case Rep 2020; 13: e231825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Squire G, Hetherington S. First reported case of lead-related infective endocarditis secondary to Capnocytophaga canimorsus: ‘Dog Scratch’ endocarditis. BMJ Case Rep 2020; 13: e233783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Igeta R, Hsu H-C, Suzuki M, et al. Compartment syndrome due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus infection: a case report. Acute Med Surg 2020; 7: e474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Liapis K, Delimpasis S. Worth a careful look at the blood film. Eur J Intern Med 2020; 73: 94–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Sri A, Droscher E, De Palma R. Capnocytophaga canimorsus and infective endocarditis-making a dog’s dinner of the aortic valve: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep 2021; 5: ytab278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. McNicol M, Yew P, Beattie G, et al. A case of Capnocytophaga canimorsus endocarditis in a non-immunosuppressed host: the value of 16S PCR for diagnosis. Access Microbiol 2021; 3: 000235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Lindén S, Gilje P, Tham J, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus tricuspid valve endocarditis. IDCases 2021; 24: e01083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Westenfield K, Glogoza M, Tierney D, et al. Mycotic aortic aneurysm due to Capnocytophaga species infection treated non-surgically. IDCases 2021; 25: e01235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Ducours M, Leitao J, Puges M, et al. An infected arterial aneurysm and a dog bite: Think at Capnocytophaga canimorsus! Infect Drug Resist 2021; 14: 2397–2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Meyer EC, Alt-Epping S, Moerer O, et al. Fatal septic shock due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus bacteremia masquerading as COVID-19 pneumonia – a case report. BMC Infect Dis 2021; 21: 736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Goetzinger JC, LaGrow AL, Shibib DR, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus bloodstream infection associated with an urticarial exanthem. Case Rep Infect Dis 2021; 2021: 9932170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. O’Riordan F, Ronayne A, Jackson A. Capnocytophaga canimorsus meningitis and bacteraemia without a dog bite in an immunocompetent individual. BMJ Case Rep 2021; 14: e242432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Tsunoda H, Nomi H, Okada K, et al. Clinical course of Capnocytophaga canimorsus bacteremia from acute onset to life crisis. Clin Case Rep 2021; 9: 266–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Rizk M-A, Abourizk N, Gadhiya KP, et al. A bite so bad: septic shock due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus following a dog bite. Cureus 2021; 13: e14668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Oliveira P, Figueiredo M, Paes de, Faria V, et al. Septic shock due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus infection in a splenectomized patient. Cureus 2021; 13: e13815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Amacher SA, Søgaard KK, Nkoulou C, et al. Bilateral acute renal cortical necrosis after a dog bite: case report. BMC Infect Dis 2021; 21: 231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Bjørkto MH, Barratt-Due A, Nordøy I, et al. The use of eculizumab in Capnocytophaga canimorsus associated thrombotic microangiopathy: a case report. BMC Infect Dis 2021; 21: 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Nakayama R, Miyamoto S, Tawara T, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus infection led to progressively fatal septic shock in an immunocompetent patient. Acute Med Surg 2022; 9: e738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Nisi F, Dipasquale A, Costantini E, et al. Surviving Capnocytophaga canimorsus septic shock: intertwining a challenging diagnosis with prompt treatment. Diagn Basel Switz 2022; 12: 260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Harrigan A, Murnaghan K, Robbins M. Double valve infective endocarditis due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus. IDCases 2022; 27: e01448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. El-Battrawy I, Ansari U, Behnes M, et al. [Dyspnea and skin rash in a 49-year-old male patient]. Internist 2017; 58: 282–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Gottwein J, Zbinden R, Maibach RC, et al. Etiologic diagnosis of Capnocytophaga canimorsus meningitis by broad-range PCR. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2006; 25: 132–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Tierney DM, Strauss LP, Sanchez JL. Capnocytophaga canimorsus mycotic abdominal aortic aneurysm: why the mailman is afraid of dogs. J Clin Microbiol 2006; 44: 649–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Haase M, Bellomo R, Morgera S, et al. High cut-off point membranes in septic acute renal failure: a systematic review. Int J Artif Organs 2007; 30: 1031–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Naka T, Haase M, Bellomo R. ‘Super high-flux’ or ‘high cut-off’ hemofiltration and hemodialysis. Contrib Nephrol 2010; 166: 181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-phj-10.1177_22799036221133234 for The Great pretender: the first case of septic shock due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus in Sardinia. A Case report and review of the literature by Salvatore Sardo, Claudia Pes, Andrea Corona, Giulia Laconi, Claudia Crociani, Pietro Caddori, Maria Luisa Boi and Gabriele Finco in Journal of Public Health Research