Abstract

Recovery of mental health in people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders is essential, thus it is very important to be assessed. One instrument that measures mental health recovery is the Recovery Assessment Scale – Domains and Stages (RAS-DS), developed within the Australian cultural context to facilitate mental health recovery. An instrument based on conceptions of mental health recovery in Indonesia is still needed. This qualitative study aimed to characterise how persons with schizophrenia spectrum disorders in Indonesia define mental health recovery, to develop the Skala Pemulihan Pasien Skizofrenia (SPPS)/Indonesian Recovery Scale for Patient with Schizophrenia (I-RSPS), and to determine the content validity of the I-RSPS. Qualitative data were collected through focus group discussions (n = 11); data were analysed using conventional content analysis and thematic analysis. An inductive approach was used to develop the I-RSPS items. Content validity was evaluated using an item-level content validity index (I-CVI) and a scale-level content validity index (S-CVI). Validity evaluation trials were conducted with ten participants. Perceptions of mental health recovery in people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders in Indonesia were investigated along social, existential, clinical, functional, and physical dimensions. Some perceptions of family, religion, and spirituality are unique to the Indonesian socio-cultural context, as are some stigmas I-RSPS consists of 40 items with good content validity, with an average I-CVI of 0.99 and an average S-CVI of 0.93, and it was rated as easy to use, with 5.4 min (range: 3–10 min) being the average duration required to complete the scale.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Schizophrenia spectrum disorders, Mental health recovery, Personal recovery

Schizophrenia; Schizophrenia spectrum disorders; Mental health recovery; Personal recovery.

1. Introduction

Traditionally, the treatment of mental health problems has focused on a cure, followed by rehabilitation to aid an individual's return to society after hospitalisation. This approach is considered to be an overly narrow biomedical approach. Consequently, the recovery-oriented approach is centred on the individual. It can be adjusted according to an individual's perceptions and values, thusly focusing not on the complete resolution of symptoms but instead on stressing resilience and control over life's problems. This approach is guided by the recovery model of mental illness (Jacob, 2015; Vanderplasschen et al., 2013). The new recovery approach was discussed in the literature for individuals with mental health problems in the 1980s. Recovery is described as a unique and highly personal process aimed at attaining a way of life that is characterised by fulfilment, hope for the future, productivity, and the ability to provide meaningful contributions, despite the limitations caused by illness (Anthony, 1993).

In 2005, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) defined mental health recovery as ‘a journey of healing and transformation enabling a person with a mental health problem to live a meaningful life in a community of his or her choice while striving to achieve his or her full potential’ (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2005). In contrast to other clinical and objective definitions, which emphasise symptom remission and functional recovery, the definition recommended by the SAMHSA emphasises humanistic values and profoundly subjective experiences as contributors to a meaningful life, despite illness (Chan and Mak, 2014). Consequently, the concepts of clinical and personal recovery must be differentiated (Slade et al., 2008; Vanderplasschen et al., 2013). For an individual with mental illness, mental health recovery is a journey of transformation towards a meaningful life within the community, following their own choices to achieve their potential (Kusumawardhani et al., 2015).

There has also been a change in how recovery is assessed, in response to changing perceptions. Over the last decade, many researchers have developed targeted instruments to evaluate mental health recovery (Sklar et al., 2013). One of the most commonly used instruments is the Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS) developed by Giffort et al., in 1995 in the United States; this was further developed by Hancock et al. (2015) into the Recovery Assessment Scale – Domains and Stages (RAS-DS) in 2015 in Australia. Individuals with mental illness were also involved in the development of the RAS-DS. This was important because client involvement in developing a tool for mental health recovery is important for preserving the philosophy of the recovery concept (Sklar et al., 2013).

Social and cultural factors play a role in supporting the recovery process. The impact of mental disorders differs across countries (Davidson et al., 2005). Culture affects how problems are defined, understood, and which solutions are deemed acceptable (Hernandez et al., 2009). Instruments developed in Western countries tend to focus on individualistic values such as self-determination and self-responsibility, with less regard for family involvement in the recovery process (Mak et al., 2018). Southeast Asian countries, including Indonesia, differ from Western countries, especially in terms of stigma, collectivism, and spirituality (Hechanova and Waelde, 2017). The stigma against people with schizophrenia is exemplified by the obstinate phenomenon of shackling or pasung in Indonesia (Human Rights Watch, 2018). The collectivist cultures of Asian countries influence a person's view of well-being, which is related to feelings of acceptance by others and belonging (Fukui et al., 2012). Spirituality and religiosity are fundamental to Indonesian culture, and their importance is emphasised in times of illness. They also affects how people perceive illnesses such as schizophrenia (Rochmawati et al., 2018). Just as recovery is highly individualised and influenced by a person's cultural background (Frese et al., 2009), cultural differences may also lead to different perceptions of mental health, treatment-seeking behaviours, and therapeutic relationships (Gopalkrishnan, 2018). Thus, the RAS, a widely used recovery scale developed in Western countries, fails to account for several elements of Indonesian culture. The only recovery scale available in the Indonesian language (Bahasa Indonesia) is the RAS-DS (Nada, 2018); as it is based on the RAS, the RAS-DS does not capture numerous Indonesian cultural characteristics.

Therefore, the Skala Pemulihan Pasien Skizofrenia (SPPS)/Indonesian-Recovery Scale for Patients with Schizophrenia (I-RSPS) should be developed based on the views of people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders in Indonesia, to better assess recovery progress among members of this population.

2. Material and methods

This qualitative study aimed to evaluate the meaning of mental health recovery in individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders in Indonesia, develop I-RSPS items, and determine the content validity of the I-RSPS. Qualitative data were collected through focus group discussions (FGDs) with patients diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. This study was conducted at the Adult Psychiatry Outpatient Clinic, Dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo General Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, via an online videoconference application, owing to the on-going coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Therefore, participants were given incentive data plan to join the FGDs. Data were collected from November 2020 to June 2021. The research protocol has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine University of Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia.

The study participants were chosen using non-probability purposive sampling. The total number of FGD participants (patients with schizophrenia) was 11 (five in the first FGD session and six in the second FGD session). Two FGD sessions were conducted and potential data saturation was assessed by researchers after the second FGD session. Ten experts were involved in this study. Ten additional participants were chosen, using non-probability consecutive sampling, to complete the I-RSPS, provide ratings of completion difficulty, and share their experiences with scale completion, during a short interview.

The additional participants inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) having schizophrenia spectrum disorders as diagnosed by a psychiatrist; (2) aged 18–59 years; (3) not in an acute condition stated by a score of 1 on all five items of the PANSS-EC; (4) minimum educational level of junior high school; and (5) agreed to participate in the study by provided written informed consent. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) diagnosis with an intellectual disability or (2) having mental disorder that was secondary to a medical illness. The authors had no prior relationships with the participants that could have impacted the research process. The experts inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) a psychiatrist at the Psychiatric Department of dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo General Hospital - Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia; (2) clinical psychiatry for at least two years; and (3) involvement in research or experience in mental health recovery concerning individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

Each FGD session was recorded digitally and transcribed verbatim using Microsoft Word. Microsoft Excel® was used to organise the transcripts and extract participants’ quotations from them. Qualitative data were analysed using the conventional content analysis approach to allow categories to flow from the data instead of fitting data into pre-conceived categories (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). We presented qualitative data using a thematic survey typology to categorise them according to themes (Sandelowski and Barroso, 2003). The I-RSPS items were developed using an inductive method based on the FGD analysis results, which involved the generation of items from the responses of individuals (Boateng et al., 2018). The content validity test was calculated using the content validity coefficient based on inter-rater expert agreement, determined via an item-level content validity index (I-CVI) and a scale-level content validity index (S-CVI).

3. Results

The mean age of all participants (n = 11) was 31.7 years (range, 21–44 years). Most participants were male (72.7%) and unmarried (90.9%). Highest education levels varied from senior high school (36.3%) to associate degree (18.2%) to bachelor's degree (45.5%). Around half of the FGD participants were unemployed (54.5%), while the others were employed (36.4%) or were housewives (9.1%). The participants were Muslim (63.6%), Catholic (27.3%), or Christian (9.1%). FGD participants came from various ethnic backgrounds in Indonesia, including Javanese (36.4%), Chinese (27.3%), Padangnese (18.2%), Minangnese (9.1%), and Bataknese (9.1%). The participants were diagnosed with schizophrenia (63.6%) or schizoaffective disorder (36.4%). The mean duration of diagnosis was nine years (range, 1–17 years). The first FGD session was conducted with five members of the Indonesian Community Care for Schizophrenia and lasted 104 min. The second FGD session was conducted with six patients and lasted 97 min.

‘...[by] the neighbours around us... we are often belittled. Having a mental disorder... we’re seen like we can’t function anymore...’ (Mr. F, 31 years old)

‘... what’s clear for me is that my spirituality is important for my recovery. I feel happy when I worship God, and I can share my burdens with God. Yeah okay, I have schizophrenia. But at least, I have to guide me...’ (Mr. H, 39 years old)

‘In my recovery, my friends is important. So I don’t just grow by myself... I also get involved in a community... in society and in friendship...’ (Mr. P, 21 years old)

‘My family helped me through my recovery... they helped me do every little things until slowly I could do things by myself again... and when I’m healthy, I can cook my children the foods they want...’ (Mrs. L, 44 years old)

From the FGD transcripts, we performed the condensation of meaning units and generated codes based on them (Mahpur, 2017). This procedure yielded 402 codes grouped into 20 categories (Table 1).

Table 1.

Category and number of codes derived from qualitative data analysis.

| No. | Category | Number of Codes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Social Life | 47 |

| 2 | Joy and Satisfaction | 46 |

| 3 | Medical Care | 43 |

| 4 | Self-control | 31 |

| 5 | Happiness and Meaning | 29 |

| 6 | Acceptance | 26 |

| 7 | Family | 24 |

| 8 | Symptoms | 24 |

| 9 | Productivity and Role | 23 |

| 10 | Activities and Routines | 18 |

| 11 | Hope | 15 |

| 12 | Religion and Spirituality | 15 |

| 13 | Stigma | 14 |

| 14 | Independence and Responsibility | 12 |

| 15 | Spouse | 11 |

| 16 | Self-care | 10 |

| 17 | Insight | 6 |

| 18 | Physical Appearance | 4 |

| 19 | Cognitive Function | 2 |

| 20 | Substance Use | 2 |

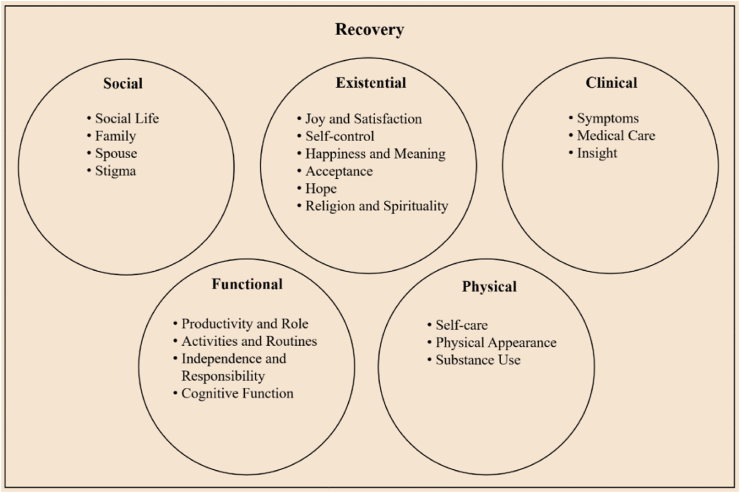

Using the recovery dimension framework developed by Whitley and Drake (2010), the 20 categories obtained from qualitative data analysis were divided into five major themes: social, existential, clinical, functional, and physical (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Components of schizophrenia spectrum disorder patient recovery.

Statements for the items were formulated by two researchers using codes from the qualitative data analysis results (examples: code = good social function → “I am able to socialise well”; code = having community → “I belong in a community”). Of these, 107 reflected aspects of mental health recovery in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. We used the Aiken index (V) (Aiken, 1985). The study was performed by five experts: three neuropsychiatric experts, a child and adolescent psychiatry expert and a psychotherapy expert. The Aiken index V coefficient ranges from 0 to 1, with a higher score indicating better validity. For I-RSPS item development, only those with a V coefficient ≥0.8 were deemed acceptable (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The pathway of I-RSPS item development.

Based on the Aiken index calculation, 37 items had a V value of ≥0.8. Based on the agreement of the researcher team, seven additional statements were included as I-RSPS items, as these items represented a category and were not interchangeable with other items. Resultantly, 44 statements were included as I-RSPS items. Thereafter, another five experts conducted a content validity test, including two community psychiatry experts, a child and adolescent psychiatry expert, a forensic psychiatry expert, and a geriatric psychiatry expert. Content validity analysis was performed using an I-CVI and an S-CVI. The I-CVI score recommended for content validity using five experts was 1.0 (Polit and Beck, 2006). However, several items with I-CVI values of 0.6 and 0.8 were still included, because these items represented an aspect of specific categories and were not interchangeable with other items. Based on the experts’ input, one item was removed because of its similarity to another item. This process resulted in 43 I-RSPS items being tested on ten participants.

Ten participants who went to Adult Psychiatry Outpatient Clinic, Dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo General Hospital from June 10th to 21 June 2021 were recruited for this study, using non-probability consecutive sampling. Participants were required to complete all 43 items of the I-RSPS and score the overall difficulty of the I-RSPS and of each I-RSPS item. Each item was scored on a scale with the following 5 levels: ‘strongly disagree’ (score = 1), ‘disagree’ (score = 2), ‘partly agree’ (score = 3), ‘agree’ (score = 4), and ‘strongly agree’ (score = 5). Higher scores indicated better personal recovery. The difficulty level of the I-RSPS was measured along a scale with the following 4 levels: ‘very difficult = 1’ difficult = 2′, ‘easy = 3’, and ‘very easy = 4’. After participants scored the difficulty level of each I-RSPS item, we performed a short interview to learn about their experiences with completing the I-RSPS.

The mean age of the participants (n = 10) was 30.5 years (range, 18–53 years). Six participants were male (60%) and most were unmarried (80%). The participants' highest educational attainment levels varied between junior high school (20%), senior high school (20%), associate degree (10%), and bachelor's degree (50%). Half of the participants were employed (50%) and the rest were unemployed (40%) or housewives (10%). Most participants were Muslim (80%) and the rest were Christians (20%). The participants' ethnic backgrounds were Javanese (30%), Sundanese (30%), Betawinese (30%), and Bataknese (10%). Participants were diagnosed with schizophrenia (80%) or schizoaffective disorder (20%), and the mean duration of diagnosis was 12.4 years (range, 1–25 years). The mean time required for participants to complete the I-RSPS was 5.4 min (range, 3–10 min). Eight participants (80%) rated the I-RSPS difficulty level as ‘easy’, and two participants (20%) rated it as ‘difficult’. The maximum score for the 43 items of the I-RSPS was 215. The mean I-RSPS score was 164.3 (range 117–197).

Eighteen items were rated as ‘difficult’ or ‘very difficult’ by participants. Of the 18 items, ten were revised without changing the meaning of the items, five were not revised as the word choices were considered appropriate, and three were omitted. After completing the revision process based on the trial results, there were 40 I-RSPS items with mean I-CVI (39.4/40) was 0.99, and mean S-CVI (37/40) was 0.93 (Table 2).

Table 2.

The I-RSPS items.

| No. | I-RSPS Items |

|---|---|

| 1 | I am able to socialise well |

| 2 | I am actively involved in social settings (e.g. participating in social events, community services, social gatherings, etc.) |

| 3 | I belong in a community (e.g. support group community, social community, religious community, etc.) |

| 4 | I have one or more friends (e.g. a friend that is willing to accept, listen to, and support me) |

| 5 | I can enjoy pleasurable activities (e.g. writing, drawing, listening to music, watching TV, etc.) |

| 6 | I can rediscover pleasurable activities (e.g. writing, drawing, listening to music, watching TV, etc.) |

| 7 | I am useful to others |

| 8 | I have personal goals |

| 9 | I put in efforts towards achieving goals |

| 10 | I can enjoy my life |

| 11 | I take my medications regularly |

| 12 | I take benefits from my prescribed medications |

| 13 | I can control my emotions (e.g. anger, sadness, etc.) |

| 14 | I can have better behaviour |

| 15 | I can live my life again |

| 16 | I value my life |

| 17 | I can be a better person |

| 18 | I can learn from my experiences |

| 19 | I can accept my illness |

| 20 | I can accept my life as it is |

| 21 | I can accept myself as I am |

| 22 | I have a good relationship with my family (e.g. supporting, understanding, accepting each other, etc.) |

| 23 | I understand the condition in my family |

| 24 | I can recognise the signs of mental illness relapse |

| 25 | I can think positively |

| 26 | My life is no longer affected by my mental illness |

| 27 | I am able to work |

| 28 | I can play my role in my family (e.g. helping parents, taking care of children, etc.) |

| 29 | I am productive (e.g. cooking, baking, making crafts, repairing things, etc.) |

| 30 | I have a regular lifestyle |

| 31 | I have hopes to recover |

| 32 | I have hope for the future |

| 33 | My religiosity supports my recovery |

| 34 | I am accepted by my neighbours |

| 35 | I can manage my finances independently (e.g. managing monthly income and expenses, etc.) |

| 36 | I can take good care of myself |

| 37 | I have a healthy lifestyle (e.g. exercising, eating healthy foods, having enough rest, etc.) |

| 38 | I have a good understanding of my mental illness |

| 39 | I understand that I need help with my mental illness |

| 40 | I can communicate with others (e.g. family, friends, health workers, new people, etc.) |

4. Discussion

This qualitative analysis resulted in the identification of 20 categories related to the recovery progress of patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Several of these categories, including ‘Social Life’, ‘Joy and Satisfaction’, ‘Happiness and Meaning’, ‘Acceptance’, ‘Self-control’, ‘Productivity and Role’, ‘Activities and Routines’, ‘Independence and Responsibility’, ‘Self-care’, and ‘Hope’, represent recovery components commonly evidenced in studies of mental health recovery (Andresen et al., 2003; Hancock et al., 2013; Leamy et al., 2011). Some of these components are also in line with mental health recovery, as it defined in the 2016 SAMHSA National Consensus Statement on Mental Health Recovery from 2006 (Kusumawardhani et al., 2015).

Hence, it is understandable that several recovery components are universal and are not influenced by ethnicity and/or culture. This understanding is also supported by a study conducted by Whitley in 2016 that compared perceptions of mental health recovery between Caribbean-Canadian and European-Canadian groups. This study reported many similarities regarding concepts, obstacles, and supporting factors for recovery, such as routine, work, social involvement, and community (Whitley, 2016). A systematic review by Leamy et al. found that the five most commonly identified categories, identified across 87 studies on personal recovery, were connectedness (86%), hope and optimism about the future (79%), identity (75%), meaning in life (66%), and empowerment (91%) (Leamy et al., 2011). These five categories were also found in this study's qualitative data, although there were differences in the grouping systems and naming of categories.

As a nation with a collectivist culture, the value and purpose of a group (e.g. a family) are of particular importance to many Indonesian people (Mangundjaya, 2013). This notion is reflected in the ‘Family’ category mentioned by most FGD participants (9 out of 11 participants), especially in statements about support and acceptance. In addition to immediate families, extended families play a significant role. A participant with a Padangnese cultural background mentioned their satisfaction with gaining appreciation from their extended family, which could be attributed to the emphasis placed on a sense of belonging within collectivist cultures (Fukui et al., 2012).

In this study, seven FGD participants identified stigma as an influence on mental health recovery. Five FGD participants explicitly mentioned external stigma. Their experience confirms that the stigmatisation of people with mental illnesses remains a problem in Indonesia (Mamnuah et al., 2017). That stigma is a crucial determinant of recovery has been highlighted in many studies (Hancock et al., 2013; Leamy et al., 2011; Whitley, 2016; Young and Ensing, 1999). Whitley et al. reported that stigma was a significant obstacle to recovery, manifesting in various layers of social life, including interactions with family, friends, clinicians, employers, and society in general (Whitley, 2016). External stigma can be internalised by individuals, causing them to acknowledge the stereotype perceived by the public (self-stigma). Self-stigmatisation may decrease self-esteem and self-efficacy (Corrigan et al., 2010; Corrigan and Rao, 2012).

Six FGD participants mentioned that their religiosity or spirituality contributed positively to their mental health recovery. One Muslim FGD participant conveyed that prayer helped him to accept his illness and that he believed God guided him throughout his recovery process. The role of religiosity and spirituality in recovery is consistent with the findings of a study by Eltaiba et al. which involved 20 Muslim participants with mental illness. The study reported that religious values contributed to recovery and were central to the recovery process. The recovery process also involved the acceptance of their illness as being part of Allah's will (Eltaiba and Harries, 2015). According to a systematic review by Leamy et al. spirituality is the least commonly identified recovery process in the literature (six out of 87 studies) and that spirituality was emphasised more among members of minority ethnicities (Leamy et al., 2011). A study by Whitley found that religion and faith in God are recovery support factors that differ in importance between the Caribbean- and European-Canadian populations (Whitley, 2016). The current results indicate that religion and spirituality are essential factors for people with mental illness in Indonesia.

In this study, clinical characteristics were essential for mental health recovery. Several such characteristics are reflected in the ‘Medical Care’, ‘Symptoms’, and’ Insight’ categories. All participants associated their mental health recovery with at least one medical treatment, including pharmaceutical and psychiatric care. Participants also emphasised the importance of regular medication use. This emphasis is also described in a study by Young and Ensing, reflected in one participant's statement, ‘the medicine is almost 90% of the battle...’ (Young and Ensing, 1999). Eight participants associated several aspects of mental illness symptoms with recovery, including symptom improvement. The specific symptoms mentioned by participants were hallucinations, delusions, and uncontrolled emotions. Several other studies have also reported that symptom improvement is essential to recovery for people with mental illnesses (Young and Ensing, 1999). Considering these ideas, we assert that symptom improvement, measured from a clinical recovery perspective, is inseparable from personal recovery. Van Eck et al. reported an association between clinical and personal recovery (r = −0.21; 95% CI = −0.27, −0.14; P < 0.001) (Van Eck et al., 2018). A study by Nada et al. of 100 adults with schizophrenia in the remission phase also showed a correlation between the Indonesian version of the RAS-DS total score and remission according to the PANSS total score (r = −0.639; P < 0.0001) (Nada, 2018). Therefore, we conclude that clinical recovery could be considered a part of personal recovery in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

This study used the I-RSPS items to evaluate and monitor personal recovery in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. The I-RSPS is self-administered based on clients' views of themselves. In addition to evaluating and monitoring recovery outcomes in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders using the total score, the I-RSPS can be used to identify and develop therapy goals, tailored to clients’ hopes for their recovery processes.

In developing a recovery assessment instrument, the strength of our study lies in the significant involvement of clients in creating and modifying I-RSPS items. Moreover, I-RSPS items were created using an inductive method based on the results of a qualitative data analysis so that the final I-RSPS items were constructed according to perceptions of mental health recovery in Indonesia. To our knowledge, this is the first project to create an instrument for evaluating recovery in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders based on clients’ perceptions, in Indonesia; that reflects the cultural context of Indonesia. The level of difficulty associated with completing the I-RSPS questionnaire was low, and the average duration for completing it was 5.4 min. Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, the FGDs faced some limitations because they were conducted using a videoconference application, which restricted the interaction and discussion between participants. We recommend that future research examine the implementation of I-RSPS in practice and its clinical value in facilitating the recovery of patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Alvin Saputra; Tjhin Wiguna: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Agung Kusumawardhani; Sylvia detri Elvira: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

Prof Tjhin Wiguna was supported by Universitas Indonesia [Hibah PUTI-NKB-4136/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2020].

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Komunitas Peduli Skizofrenia Indonesia (KPSI)/Indonesian Community Care for Schizophrenia and all the participants who supported this study.

References

- Aiken L.R. Three coefficients for analyzing the reliability and validity of ratings. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1985;45:131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Andresen R., Oades L., Caputi P. The experience of recovery from schizophrenia: towards an empirically validated stage model. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatr. 2003;37:586–594. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony W.A. Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc Rehabil. J. 1993;16:11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Boateng G.O., Neilands T.B., Frongillo E.A., Melgar-Quiñonez H.R., Young S.L. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: a primer. Front. Public Health. 2018;6 149 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K.K.S., Mak W.W.S. The mediating role of self-stigma and unmet needs on the recovery of people with schizophrenia living in the community. Qual. Life Res. 2014;23:2559–2568. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0695-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P.W., Rao D. On the self-stigma of mental illness: stages, disclosure, and strategies for change. Can. J. Psychiatr. 2012;57:464–469. doi: 10.1177/070674371205700804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P.W., Morris S., Larson J., Rafacz J., Wassel A., Michaels P., Wilkniss S., Batia K., Rüsch N. Self-stigma and coming out about one’s mental illness. J. Community Psychol. 2010;38:259–275. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L., Borg M., Marin I., Topor A., Mezzina R., Sells D. Processes of recovery in serious mental illness: findings from a multinational study. Am. J. Psychiatr. Rehabil. 2005;8:177–201. [Google Scholar]

- Eltaiba N., Harries M. Reflections on recovery in mental health: perspectives from a Muslim culture. Soc. Work. Health Care. 2015;54:725–737. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2015.1046574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frese F.J., Knight E.L., Saks E. Recovery from schizophrenia: with views of psychiatrists, psychologists, and others diagnosed with this disorder. Schizophr. Bull. 2009;35:370–380. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui S., Shimizu Y., Rapp C.A. A cross-cultural study of recovery for people with psychiatric disabilities between U.S. and Japan. Commun. Ment. Health J. 2012;48:804–812. doi: 10.1007/s10597-012-9513-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalkrishnan N. Cultural diversity and mental health: considerations for policy and practice. Front. Public Health. 2018;6:179. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock N., Bundy A., Honey A., Helich S., Tamsett S. Measuring the later stages of the recovery journey: insights gained from clubhouse members. Community Ment. Health J. 2013;49:323–330. doi: 10.1007/s10597-012-9533-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock N., Scanlan J.N., Honey A., Bundy A.C., O’Shea K. Recovery assessment scale – Domains and stages (RAS-DS): its feasibility and outcome measurement capacity. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatr. 2015;49:624–633. doi: 10.1177/0004867414564084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hechanova R., Waelde L. The influence of culture on disaster mental health and psychosocial support interventions in Southeast Asia. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2017;20:31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez M., Nesman T., Mowery D., Acevedo-Polakovich I.D., Callejas L.M. Cultural competence: a literature review and conceptual model for mental health services. Psychiatr. Serv. 2009;60:1046–1050. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.8.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H.-F., Shannon S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch Indonesia: shackling reduced. But Persists. 2018 https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/10/02/indonesia-shackling-reduced-persists [WWW Document]. URL. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob K.S. Recovery model of mental illness: a complementary approach to psychiatric care. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2015;37:117–119. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.155605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusumawardhani A., Dharmono S., Amir N., Diatri H., Malik K. Centra Communications; Jakarta: 2015. From Curing to Caring: Achieving Patient’s Recovery Rekomendasi Tata Laksana Layanan Skizofrenia. [Google Scholar]

- Leamy M., Bird V., Le Boutillier C., Williams J., Slade M. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2011;199:445–452. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahpur M. Fakultas Psikologi Universitas Islam Negeri Malang; Malang: 2017. Memantapkan Analisis Data Kualitatif Melalui Tahapan Koding. [Google Scholar]

- Mak W.W.S., Chan R.C.H., Yau S.S.W. Development and validation of Attitudes towards Recovery Questionnaire across Chinese people in recovery, their family carers, and service providers in Hong Kong. Psychiatr. Res. 2018;267:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamnuah, Nurjannah I., Prabandari Y.S., Marchira C.R. Literature review of mental health recovery in Indonesia. GSTF. Nurs. Heal. Care. 2017;3 [Google Scholar]

- Mangundjaya W. In: Steering Cultural Dynamics: Selected Papers from the 2010. Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology. Kasima Y., Kashima E.S., Beatson R., editors. International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology; Melbourne: 2013. Is there cultural change in the national cultures of Indonesia? [Google Scholar]

- Nada K. Universitas Indonesia; Jakarta: 2018. Uji Kesahihan Dan Keandalan Instrumen Recovery Assessment Scale - Domains and Stages (RAS-DS) Versi Bahasa Indonesia. [tesis] [Google Scholar]

- Polit D.F., Beck C.T. The content validity index: are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health. 2006;29:489–497. doi: 10.1002/nur.20147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochmawati E., Wiechula R., Cameron K. Centrality of spirituality/religion in the culture of palliative care service in Indonesia: an ethnographic study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2018;20:231–237. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M., Barroso J. Classifying the findings in qualitative studies. Qual. Health Res. 2003;13:905–923. doi: 10.1177/1049732303253488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklar M., Groessl E.J., O’Connell M., Davidson L., Aarons G.A. Instruments for measuring mental health recovery: a systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013;33:1082–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade M., Amering M., Oades L. Recovery: an international perspective. Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc. 2008;17:128–137. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00002827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville: 2005. National Consensus Conference on Mental Health Recovery and Systems Transformation. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck R.M., Burger T.J., Vellinga A., Schirmbeck F., De Haan L. The relationship between clinical and personal recovery in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Bull. 2018;44:631–642. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderplasschen W., Rapp R.C., Pearce S., Vandevelde S., Broekaert E. Mental health, recovery, and the community. Sci. World J. 2013;2013:926174. doi: 10.1155/2013/926174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley R. Ethno-racial variation in recovery from severe mental illness: a qualitative comparison. Can. J. Psychiatr. 2016;61:340–347. doi: 10.1177/0706743716643740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley R., Drake R.E. Recovery: a dimensional approach. Psychiatr. Serv. 2010;61:1248–1250. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.12.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young S.L., Ensing D.S. Exploring recovery from the perspective of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 1999;22:219. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.