Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Posterior Cortical Atrophy (PCA) is one of the atypical Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) variants, characterized by predominant visuospatial and visuoperceptual deficits, with established dorsal and ventral subtypes. A third primary occipital (caudal) variant has been suggested. We aimed to determine its demographics, clinical manifestations, and biomarker findings.

METHODS:

Fifty-two PCA patients were investigated. Patients underwent neuropsychological assessment, MRI imaging and FDG-, amyloid- and tau-PET scans. Normalized regional FDG-PET values were represented as z-scores relative to a control population. Patients were divided into “primary occipital” and “other PCA” subgroups according to FDG-PET defined criteria, with primary occipital defined as patients in which the z-scores for occipital subregions were at least one standard deviation lower (i.e., more abnormal) than the z-scores in all other brain regions. Global amyloid-PET, temporoparietal FDG-PET and temporal tau-PET regions-of-interest (ROI) were calculated.

RESULTS:

Nine patients were classified as primary occipital; they were older (p=0.034) and had more years of education (p=0.007) than other PCA patients. Primary occipital group performed worse on the Ishihara test for color perception (p<0.001), while other PCA patients performed worse on the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) praxis scale (p=0.005). Overall neuropsychiatric symptom burden was lower in the primary occipital group (p<0.001). The FDG-PET meta-ROI was higher in the primary occipital subtype (p=0.006), but no differences were observed in amyloid and tau-PET.

CONCLUSIONS:

Our findings suggest primary occipital PCA is characterized by an older age-at-onset, more color perception dysfunction, less severe ideomotor apraxia and less hypometabolism in temporal-parietal meta-ROI compared to established phenotypes.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Posterior Cortical Atrophy, Visuospatial Impairment

Introduction

Considerable heterogeneity is evident among atypical Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) patients, with phenotypes characterized on the basis of dominant presenting clinical manifestations, involving visual, language, behavioral and executive domains1. One of the recognized atypical early-onset AD variants is Posterior Cortical Atrophy (PCA), a clinico-radiological syndrome characterized by progressive visuospatial and visuoperceptual abnormalities2–4 localizing to posterior cortical regions. The majority of PCA patients can be further sub-categorized into right or left dorsal variants5, characterized by prominent spatial impairment and evidence of Balint syndrome with pathology burdening the occipito-parietal regions, and the minority of patients categorized as ventral type, presenting with visual object agnosia and prosopagnosia, pathologically involving the occipito-temporal regions1,6.

In addition to the two above-mentioned variants, case reports suggest a rarer third phenotype of a basic-visual/caudal/primary-occipital variant7–9. However, description of this variant has been limited with little understanding of how it differs from the more well recognized phenotypes. The objective of the current study was to determine whether the primary occipital subtype can be differentiated from other PCA subtypes by clinical and imaging parameters.

Methods

Study subjects and protocol

The PCA cohort consisted of 52 amyloid-positive patients who met clinical diagnostic criteria for PCA4. All patients were prospectively recruited by the Neurodegenerative Research Group (NRG) at Mayo Clinic between March 2013 and December 2021. All patients underwent a comprehensive neurological evaluation by a board-certified behavioral neurologist, neuropsychological testing, 3T volumetric brain MRI, FDG-PET, and Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) amyloid-PET. A sub-set (n=38) also had tau-PET scans using [18F] flortaucipir.

All patients gave informed consent to take part in the project and the project protocol was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Neurological and neuropsychological evaluations

Clinical evaluations were performed as previously described10. One of two Behavioral Neurologists assessed the PCA patients (KAJ, JGR). The neurological evaluation included the Montreal Cognitive Assessment battery (MoCA) to assess general cognitive function, the brief questionnaire version of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI-Q) to assess psychiatric and behavioral features, Ishihara test to assess color-vision11, and the Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) Part III to assess parkinsonism. A visual acuity test was performed at the bedside for every patient and no differences between groups were detected. Simultanagnosia was assessed using images of overlapping line drawings, images of fragmented numbers, and images of objects/letters whose shape was created from smaller items; A 20-point scale was used to determine the score, with scores under 15 considered positive. Detection of oculomotor apraxia, optic ataxia and finger agnosia were documented. A psychometrist administered all neuropsychological tests under the supervision of a board-certified Neuropsychologist (MMM) as previously described10. These tests included the Visual Object and Space Perception (VOSP) Battery incomplete letters test to measure visuoperceptual function, the Rey-Osterrieth (Rey-O) complex figure copy trial to measure visuoconstructional abilities, and the Boston Naming Test (BNT) to assess confrontational word retrieval. The Rey-O score was expressed as the Mayo Older American Normative (MOANS) age-adjusted scale scores which are calculated to have a mean of 10 and a standard deviation of 3.

Imaging measures

All patients underwent a standardized MRI protocol on a 3.0 Tesla MRI (GE) scanner that included a 3D magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE), and FDG-PET, PiB-PET and [18F]flortaucipir PET on a PET/CT scanner, as previously described12. Individual-level patterns of FDG-PET hypometabolism were analyzed using 3D stereotactic surface projections using CortexID suite (GE Healthcare https://www.gehealthcare.co.uk/-/media/13c81ada33df479ebb5e45f450f13c1b.pdf) whereby activity at each voxel is normalized to the pons and z-scored to an age-segmented normative database (consisting of 294 healthy controls, age 31–89 years). To define the primary occipital sub-group, z-scores from four occipital regions-of-interest (ROIs) (left and right lateral occipital and primary visual) were compared to z-scores from all other ROIs across the brain (lateral and medial prefrontal, sensorimotor, anterior and posterior cingulate, precuneus, inferior and superior parietal, lateral and medial temporal and cerebellum). Patients were classified as primary occipital if the z-scores for occipital subregions were at least one standard deviation lower (i.e., more abnormal) than the z-scores in all other brain regions. Patients in which these criteria were not met were classified as “other PCA”. This process resulted in nine primary occipital patients. All patients categorized as “other PCA” had at least one other region affected to a similar degree as the occipital regions, according to FDG-PET z-scores (i.e., at least one region with a z-score within one standard deviation of an occipital region). Patient categorization was visually confirmed by consensus FDG-PET scan review (JGR, KAJ, JLW, DS). All FDG-PET SUVR images were normalized to Mayo Clinic Adult Lifespan Template (MCALT) space and smoothed at 6mm full-width-at-half-maximum to allow voxel-level comparisons.

Summary metrics for the PET scans were also calculated as previously described13. Briefly, a PiB global standardized uptake ratio (SUVR) was generated using cerebellar crus grey matter as the reference region and values greater than 1.48 were used to determine amyloid positivity. An AD-signature FDG-PET meta-ROI was generated by calculating weighted median uptake in angular gyrus, posterior cingulate, and inferior temporal ROIs, normalized to the pons and vermis. An AD-signature tau-PET meta-ROI was generated by calculating weighted median uptake across medial and lateral temporal ROIs, normalized to the cerebellar crus grey matter. The MCALT atlas was used to output regional grey matter volumes for the patients which were corrected for total intracranial volume.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients were summarized using means and SDs for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. Student’s T test and Fisher’s exact test were used to investigate differences in demographics, clinical findings, and imaging biomarkers between the groups. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS statistical software programme (IBM Corp., Version 28.0. Armonk, NY). Statistical significance was established at p<0.05. Voxel-wise t-tests in SPM12 were used for statistical comparisons of baseline FDG-PET for primary occipital versus other PCA including age and sex as covariates.

Data availability statement

Anonymized data will be shared by request from any qualified investigator.

Results

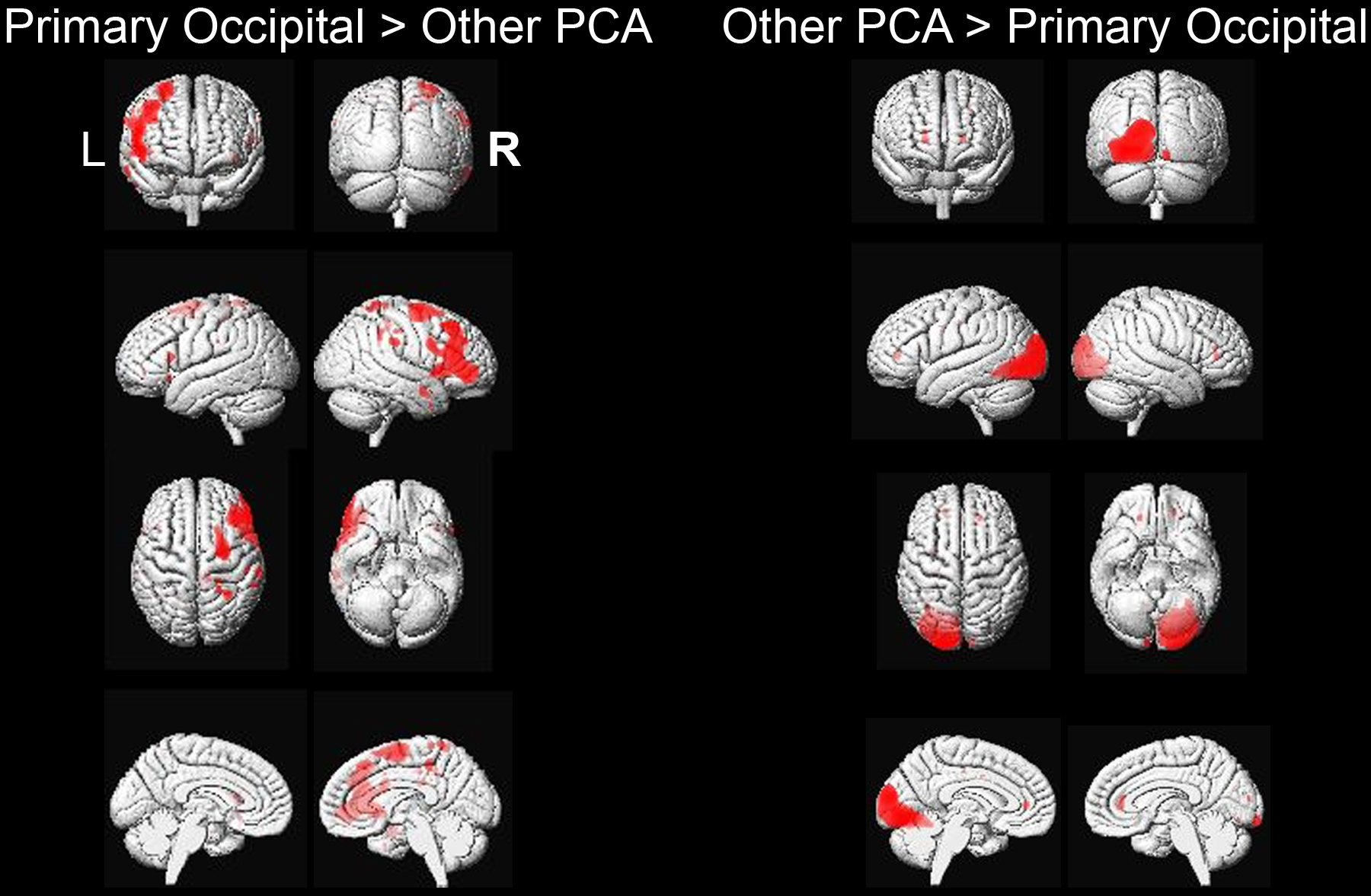

Patients categorized as primary occipital PCA had lower FDG-PET z-scores in occipital lateral or primary visual regions (mean −4.98, ± 0.77) compared to other PCA patients (−4.2 ± 1.2, p=0.039), with results surviving a false discovery rate correction for multiple comparisons at p<0.05 (Figure 1A). The other PCA patients showed lower metabolism predominantly in frontal and parietal regions, particularly on the right, compared to the primary occipital patients, although results did not survive correction for multiple comparisons (Figure 1A). Figure 1B shows single-patient images for each neuroimaging measure across PCA variants.

Figure 1.A.

SPM results comparing FDG-PET hypometabolism of primary occipital versus other PCA patients, uncorrected for multiple comparisons at p<0.001. Results have been overlaid on a 3D brain render that was constructed using averaged brain segmentations from 202 cognitively normal and Alzheimer’s disease patients (https://www.nitrc.org/projects/mcalt/).

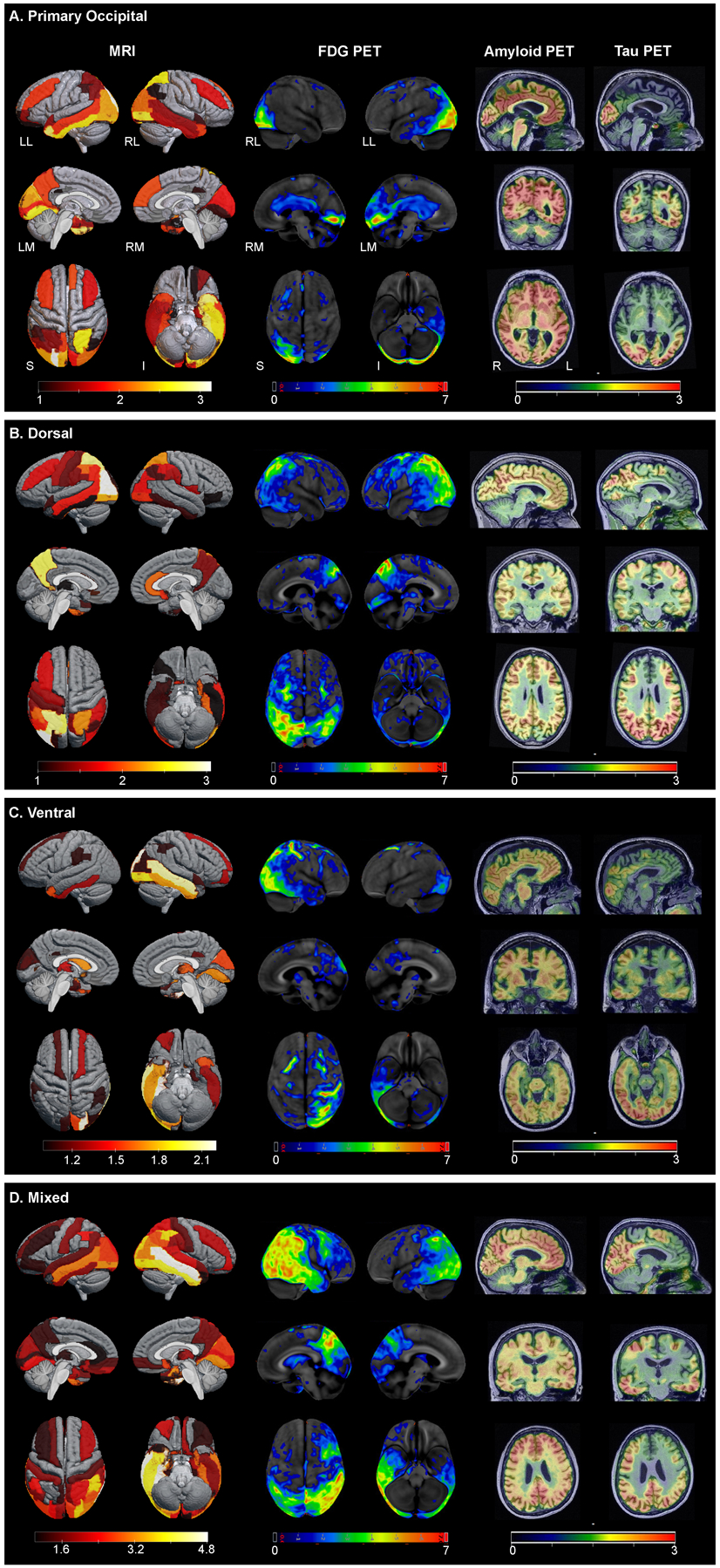

Figure 1.B.

Structural MRI (left), FDG-PET (center), and amyloid- and tau-PET (right) across PCA phenotypes: (A) Primary Occipital; (B) Dorsal; (C) Ventral; (D) Mixed. Representatives of the different phenotypes were selected based on visual inspection and confirmed by consensus FDG-PET scan review (JGR, KAJ, JLW, DS). The left MRI panels show regional Z scores depicting volume loss compared to controls on three-dimensional brain renderings using MRIcroGL Viewer. Grey regions are within the volume range of healthy controls, while colored areas indicate volume loss, white indicating the greatest volume loss. Middle panels show Z-scores, relative to a normative database, of pons intensity normalized FDG-PET scans for each individual displayed on stereotactic surface projections using Cortex ID (GE Healthcare Waukesha, WI, USA). Red color indicates greater hypometabolism. The cerebellar crus intensity normalized Amyloid- and Tau-PET scans are overlaid on the grey matter segmentations of each patient’s own T1 weighted structural MRI scan. Red color indicates higher intensity of tracer.

LL – Left Lateral, RL – Right Lateral, LM – Left Medial, RM – Right Medial, S – Superior, I – Inferior.

Differences in demographics, clinical features and imaging biomarkers are shown in Table 1. Patients classified as primary occipital PCA were older (p=0.034) and had more years of education (p=0.007) compared to the other PCA patients. Behavioral and psychiatric symptomatology evaluation based on the NPI-Q revealed lower severity score for primary occipital patients, (p<0.001). Primary occipital patients performed better on the WAB praxis test (p=0.005). The Ishihara test, however, presented a more severe clinical picture in primary occipital patients compared to other PCA patients (p<0.001). There were no group differences in the frequency of visual field defects or performance on neuropsychological tests. In terms of Lewy Body associated features, MDS-UPDRS assessment revealed worse scores among other PCA patients (p=0.006) in comparison to primary occipital patients. There were no differences in the frequency of hallucinations or REM-behavior sleep disorder between the groups. Comparison of FDG-PET meta-ROI showed higher uptake for primary occipital subtype (p=0.006). There were no significant differences between the groups when comparing amyloid-PET global SUVR, tau-PET temporal meta-ROI, or hippocampal volume.

Table 1.

Comparison of Baseline Data Between Primary Occipital and Other PCA Patients

| Primary Occipital | Other PCA | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 9 | 43 | |

| Female | 7/9 (77.8) | 27/43 (62.8) | 0.47b |

| Age at onset, y | 64.8 ± 6.9 | 59.3 ± 6.8 | 0.034 a |

| Age at FDG PET scan, y | 70.2 ± 5.9 | 63.04 ± 6.6 | 0.004 a |

| Disease duration † , y | 4.84 ± 2.04 | 3.71 ± 2.45 | 0.204a |

| Education, y | 17.7 ± 1.7 | 15.1 ± 2.6 | 0.007 |

| APOE carrier | 2/7 (28.6) | 20/38 (52.6) | 0.414b |

| Hallucinations | 0/3 (0) | 3/11 (27.3) | 1b |

| Oculomotor apraxia | 0/9 (0) | 13/40 (32.5) | 0.089b |

| Optic ataxia | 3/9 (33.3) | 11/40 (27.5) | 0.702b |

| REM sleep behavior disorder | 2/9 (33.3) | 5/25 (20) | 0.596b |

| Rey-O MOANS # | 2.11 ± 0.33 | 2.26 ± 1.31 | 0.731a |

| Ishihara Test score | 0.11 ± 0.33 | 1.5 ± 1.812 | <0.001 a |

| Visual Field Defect | 3/6 (50) | 10/18 (55.6) | 0.653b |

| Simultanagnosia ‡ | 9/9 (100) | 33/39 (84.6) | 0.578b |

| Calculation (/5) | 2.17 ± 1.6 | 1.76 ± 1.56 | 0.573a |

| Finger Agnosia | 3/6 (50) | 13/29 (44.8) | 1b |

| MoCA Score (/30) | 20.33 ± 4.82 | 17.56 ± 6.2 | 0.217a |

| NPI-Q Severity Score | 1.11 ± 1.364 | 4.14 ± 3.51 | <0.001 a |

| WAB Praxis score § | 58.78 ± 2.048 | 55.36 ± 5.876 | 0.005 a |

| VOSP Letters score (/20) | 13.5 ± 6.118 | 10.84 ± 6.778 | 0.319a |

| VOSP Cubes score (/10) | 2.5 ± 2.673 | 2.76 ± 2.911 | 0.822a |

| MDS-UPDRS III score ◊ | 1.11 ± 1.453 | 5.05 ± 8.191 | 0.006 a |

| Boston Naming Test (/15) | 11.5 ± 2.619 | 12.27 ± 2.82 | 0.486a |

| Amyloid-PET Global SUVR | 2.35 ± 0.28 | 2.37 ± 0.37 | 0.883a |

| FDG-PET meta-ROI ‖ | 1.4 ± 0.19 | 1.14 ± 0.2 | 0.006 a |

| Tau PET temporal meta-ROI ¶ | 1.54 ± 0.11 | 1.48 ± 0.28 | 0.62a |

| Total Intracranial Volume | 1432.5 ± 155.1 | 1516.8 ± 152.9 | 0.14a |

| Hippocampal Volume (left) | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.03 | 0.793a |

| Hippocampal Volume (right) | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.891a |

Categorical variables (%), continuous variables (±SD).

Disease duration is time from symptom onset to baseline visit.

Mean 10, standard deviation 3.

Simultanagnosia was measured on a 20-point scale with score below 15 considered positive.

WAB-Praxis scores rank praxis severity as follows: 0–25 is very severe, 26–50 is severe, 51–75 is moderate, and 76–plus is mild.

The Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale III score ranges from 0 to 199 with higher scores indicating more disability.

FDG-PET meta-ROI includes voxel-number weighted average of the median uptake in the angular, posterior cingulum, and temporal regions normalized by the pons and vermis.

Tau temporal meta-ROI includes: Hippocampus, Amygdala, Entorhinal Cortex, Para-hippocampal Cortex.

Abbreviations: PCA, Primary Occipital Atrophy. RBD, REM behavior disorder. MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment. NPI-Q, Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire. WAB, The Western Aphasia Battery. VOSP, Visual object and space perception. UPDRS, Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale. BNT, Boston naming test. TIV, total intracranial volume.

Independent T-test.

Fisher’s exact test.

Discussion

Our study evaluated an underrecognized PCA variant, characterized by focally localized occipital-predominant hypometabolism on FDG-PET. We found that this occipital phenotype is characterized by older age at onset and greater difficulty in color discrimination on the Ishihara test, but less ideomotor apraxia, absence of parkinsonism, and a milder degree overall symptom severity, including fewer neuropsychiatric features compared to the more recognized phenotypes. There were no significant differences in higher-order object and space perception (e.g., simultanagnosia score, visual object and space perception letters or cubes scores). Parkinsonism is not an uncommon finding in the young onset AD population14 and prior research has shown that PCA patients can have features of Lewy body disease such as parkinsonism and hallucinations15. Interestingly, parkinsonism was rare in the primary occipital group compared to the other more well recognized PCA variants, and there were no differences in other features of Lewy body disease.

Our findings showed that the primary occipital phenotype has more localized deficits and milder clinical severity than the dorsal and ventral PCA phenotypes, despite comparable disease duration and a similar degree of amyloid and tau pathology. Additional tests of basic visual function will improve future characterizations of the occipital variant. Whether this data supports the existence of a distinctive phenotype and not merely a different time point on the progressive PCA continuum is unclear. Longitudinal data will determine whether the occipital variant evolves into a ventral, dorsal or mixed phenotype.

DISCLOSURES OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. Lowe receives research support from GE Healthcare, Siemens Molecular Imaging, AVID Radiopharmaceuticals, and the NIH (NIA, NCI) and consults for Bayer Schering, Piramal Life Sciences, Life Molecular Imaging, Eisai, Inc., AVID Radiopharmaceuticals, and Merck Research.

The other authors declare no financial or other conflict of interest.

Dr. Graff-Radford is funded by the NIH and serves on the editorial board for Neurology.

The study was funded by National Institutes of Health grant R01-AG50603 (PI Dr. Whitwell) and the Alzheimer’s Association.

References

- 1.Graff-Radford J, Yong KXX, Apostolova LG, et al. New insights into atypical Alzheimer’s disease in the era of biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20(3):222–234. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30440-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitwell JL, Dickson DW, Murray ME, et al. Neuroimaging correlates of pathologically defined subtypes of Alzheimer’s disease: A case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(10):868–877. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70200-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang-Wai DF, Graff-Radford NR. Looking into posterior cortical atrophy: Providing insight into Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011;76(21):1778–1779. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821ccd4f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crutch SJ, Schott JM, Rabinovici GD, et al. Consensus classification of posterior cortical atrophy. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2017;13(8):870–884. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Townley RA, Botha H, Graff-Radford J, et al. Posterior cortical atrophy phenotypic heterogeneity revealed by decoding 18F-FDG-PET. Brain Commun. 2021;3(4):1–13. doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcab182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nestor PJ, Caine D, Fryer TD, Clarke J, Hodges JR. The topography of metabolic deficits in posterior cortical atrophy (the visual variant of Alzheimer’s disease) with FDG-PET. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(11):1521–1529. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.11.1521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levine DN, Lee JM, Fisher CM. The visual variant of alzheimer’s disease: A clinicopathologic case study. Neurology. 1993;43(2):305–313. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.2.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galton CJ, Patterson K, Xuereb JH, Hodges JR. Atypical and typical presentations of Alzheimer’s disease: A clinical, neuropsychological, neuroimaging and pathological study of 13 cases. Brain. 2000;123(3):484–498. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.3.484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickerson BC, McGinnis SM, Xia C, et al. Approach to atypical Alzheimer’s disease and case studies of the major subtypes. CNS Spectr. 2017;22(6):439–449. doi: 10.1017/S109285291600047X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabere M, Thu Pham NT, Graff-Radford J, et al. Automated Hippocampal Subfield Volumetric Analyses in Atypical Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020;78(3):927–937. doi: 10.3233/JAD-200625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pache M, Smeets CHW, Gasio PF, et al. Colour vision deficiencies in Alzheimer’s disease. Age Ageing. 2003;32(4):422–426. doi: 10.1093/ageing/32.4.422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitwell JL, Tosakulwong N, Weigand SD, et al. Relationship of APOE, age at onset, amyloid and clinical phenotype in Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2021;108:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2021.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jack CRJ, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, et al. Defining imaging biomarker cut points for brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(3):205–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jang H, Jang YK, Park S, et al. Presynaptic dopaminergic function in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease: an FP-CIT image study. Neurobiol Aging. 2020;86:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Boeve BF, et al. Visual hallucinations in posterior cortical atrophy. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(10):1427–1432. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.10.1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be shared by request from any qualified investigator.