Abstract

Objectives

To describe retracted papers originating from paper mills, including their characteristics, visibility, and impact over time, and the journals in which they were published.

Design

Cross sectional study.

Setting

The Retraction Watch database was used for identification of retracted papers from paper mills, Web of Science was used for the total number of published papers, and data from Journal Citation Reports were collected to show characteristics of journals.

Participants

All paper mill papers retracted from 1 January 2004 to 26 June 2022 were included in the study. Papers bearing an expression of concern were excluded.

Main outcome measures

Descriptive statistics were used to characterise the sample and analyse the trend of retracted paper mill papers over time, and to analyse their impact and visibility by reference to the number of citations received.

Results

1182 retracted paper mill papers were identified. The publication of the first paper mill paper was in 2004 and the first retraction was in 2016; by 2021, paper mill retractions accounted for 772 (21.8%) of the 3544 total retractions. Overall, retracted paper mill papers were mostly published in journals of the second highest Journal Citation Reports quartile for impact factor (n=529 (44.8%)) and listed four to six authors (n=602 (50.9%)). Of the 1182 papers, almost all listed authors of 1143 (96.8%) paper mill retractions came from Chinese institutions and 909 (76.9%) listed a hospital as a primary affiliation. 15 journals accounted for 812 (68.7%) of 1182 paper mill retractions, with one journal accounting for 166 (14.0%). Nearly all (n=1083, 93.8%) paper mill retractions had received at least one citation since publication, with a median of 11 (interquartile range 5-22) citations received.

Conclusions

Papers retracted originating from paper mills are increasing in frequency, posing a problem for the research community. Retracted paper mill papers most commonly originated from China and were published in a small number of journals. Nevertheless, detected paper mill papers might be substantially different from those that are not detected. New mechanisms are needed to identify and avoid this relatively new type of misconduct.

Introduction

Scientific misconduct, which includes plagiarism, fabrication, and falsification of data or images, is the most common cause of retraction of biomedical papers.1 2 Fraudulent papers have negative consequences for the scientific community and the general public, engendering distrust in science, false claims of drug or device efficacy, and unjustified academic promotion, among other problems. Moreover, misconduct encompasses other unethical practices that are often difficult to detect, such as undeclared competing interests, authorship issues, and duplicated publication.3

As scientific findings evolve and publication of science is modernised, new types of misconduct and fraud emerge. One example is the use of the so-called paper mills. In scientific publishing, the term paper mill refers to for-profit organisations that engage in the large scale production and sale of papers to researchers, academics, and students who wish to, or have to, publish in peer reviewed journals, both national and international. Many paper mill papers included fabricated data.4 We refer to this process as ghost fabrication to distinguish the process from ghost writing.

According to the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE), these organisations prepare manuscripts and seek to sell them. In some cases, they sell the authorship before publication, they then handle the submission and the peer review process. Other organisations sell the authorship after the manuscript has been accepted for publication in a legitimate scientific journal. When this scenario occurs, the organisation includes the author or authors who bought the authorship on the list of named authors, which amounts to a (sometimes total) change in authorship.4 In addition to selling the authorship of scientific papers, these organisations offer other services, ranging from making available or fabricating a database on which a study can be based, to falsifying a journal peer review so as to enable a paper to be published more easily.5 Paper mills have now broadened their service portfolio, by offering citations to papers already published by researchers on their own studies.6 Some of these organisations claim to have links with scientific journals, thereby ensuring publication of the manufactured manuscript.7 8

Paper mill papers are a growing problem with important potential consequences because they amount to systematic manipulation of the scientific publication process, as well as dissemination of false results. Additionally, publication of paper mill papers artificially inflates researchers’ curriculum without merit and diminishes trust in the scientific enterprise. This type of fraud has already given rise to various retractions and Retraction Watch, a well known organisation with a blog of retractions that dates from 2010, maintains a database of retracted articles that includes paper mill publication as a reason for retraction since 2021.9 As a relatively novel situation, the way of working and characteristics of these paper mills are not very well known, although Retraction Watch has published the results of a research into how the best known paper mill in Russia operates.10 Even so, little is known about what types of authors use the services of paper mills, in what types of journals they publish, in which fields, and the prestige of the journals in which they publish, based on their impact factor.

Thus, our objective was to analyse the trend in papers retracted for originating from paper mills; to characterise the papers retracted for this reason, along with the journals in which they were published; and to analyse their impact and visibility by reference to the number of citations received.

Methods

Study design and data collection

We conducted a cross sectional analysis of all papers retracted for being paper mill papers, from 1 January 2004, the year of publication of the first paper mill paper identified, until 26 June 2022, the date when we last accessed the database. These papers were identified via the Retraction Watch database,9 using the filter “Reason for retraction” and choosing the option “Paper mill.” We included all papers retracted for this reason and excluded papers bearing an expression of concern, where scientific misconduct had not been confirmed.

All the variables of interest were collected and stored in a purposely designed database. To conduct this study, we used three main data sources: the Retraction Watch database, Web of Science, and Journal Citation Reports (both belonging to Clarivate Analytics). Additionally, we consulted the full text of the papers included to record information related to the characteristics of the paper, such as the date of submission and publication, authors’ statement of funding, and competing interests.

Retraction Watch database

Retraction Watch tracks scientific publications, regardless of language, that have been retracted and aggregates them into a publicly available database, including different variables of interest extracted by their staff. This database includes more than 30 000 retractions and expressions of concern.9

The Retraction Watch database has higher coverage of retractions than PubMed and CrossRef because these databases use different sources to detect retracted articles and notices of retraction. The main sources for the identification of retractions are publishers’ and editors’ websites, but reports of scientific integrity investigations, social media sites, and tips from their blog followers are also checked. Staff at Retraction Watch use PubMed and Web of Science to double check the retractions. To identify retractions, staff at Retraction Watch run protocolised manual searches daily using keywords such as “retraction,” “withdrawn,” or “retracted paper.”

Retraction Watch uses mainly the information included in the notice of retraction to classify retractions into different reasons. Retraction Watch also manually checks other sources for clarification of information, such as institutional investigation reports and US Office of Research Integrity reports.

In the specific case of paper mill products, Retraction Watch’s identification is based on several indicators. One is the notice of retraction, some clearly state that the paper is from a paper mill, others use a euphemism for paper mill such as “third party editing service.” In other cases, journals and publishers retract a large number of articles accompanied by an editorial indicating that the retracted papers were from paper mills. These editorials usually use a similar language, stating that the paper “resembles different papers from different authors.” Retraction Watch also uses PubPeer and the list of probable paper mill papers published by Elisabeth Bik and other investigators.11

We sourced the total number of papers retracted for any reason per year and the total number retracted for originating from paper mills per year. For every paper retracted for the reason of originating from a paper mill, we collected the following: title of paper; number of authors; authors’ affiliated country; first author’s institution; type of institution of first author (hospital, university, research centre); and paper’s date of publication and date of retraction. The last access to the database was 26 June 2022.

Web of Science

We retrieved the total number of papers published per year across the study period (1 January 2004 to 26 June 2022) with no exceptions. For every paper included, we collected the total number of citations received, both before and after retraction, from date of publication until 26 June 2022.

Journal Citation Reports

We gathered data for the journal that published each paper and its characteristics, such as its name, Journal Citation Reports impact factor, Journal Citation Reports category, and relative position by Journal Citation Reports quartile (ie, the highest impact factor of journals belonging to the first quartile (or Q1) and the lowest impact factor journals to the fourth quartile (or Q4)), and publication modality (open access or subscription). Where the journal was included in more than one category, we chose the highest position according to the journal impact factor. We categorised hybrid journals as non-Open Access journals.

Statistical analysis

We used a descriptive analysis of the characteristics of the retracted papers identified, by reference to the variables of interest, with continuous variables being expressed as median and interquartile range, and categorical variables as absolute number and relative frequency.

We calculated the publication rate of papers that were retracted because of paper mills per 100 000 papers published in a given year, over the total number of papers published for the same year. Therefore, we assessed the proportion of papers mill publications regarding the total number of publications in each year of the study period. Additionally, we calculated the percentage of paper mill papers retracted per year, with respect to the total number of retractions per year, to ascertain the proportion of paper mill retractions compared with retractions for any other reason.

We described the distribution of this type of papers by Journal Citation Reports category of the journal in which they were published. We created a ranking of journals and publishers based on the number of retracted paper mill papers they published during the study period. We have determined if the journal of publication was reliable, that is, not suspected of being a predatory journal, in the subsample of the scientific journals that published the most retracted paper mill papers. To assess the reliability of a journal, we used the ThinkCheckSubmit checklist (https://thinkchecksubmit.org/journals).

We calculated the time elapsed between the paper’s submission and publication and the time elapsed between the paper’s publication and retraction, in days. Analysis of the times elapsed between submission and publication and the times between publication and retraction were stratified by the Journal Citation Reports quartile of the journal in which the paper was published. Similarly, we analysed the total citations received by the papers, both overall and stratified by quartile. All statistical analyses were done using the Stata version 17.0 computer software programme.

Patient and public involvement

This research was done on agreement with Retraction Watch, where we committed to use a database under specific circumstances, including confidential uses, and to avoid sharing the downloaded database with third parties. We did not test any especific health intervention or drug, therefore, we did not think that patient or public involvement would be helpful in this research.

Results

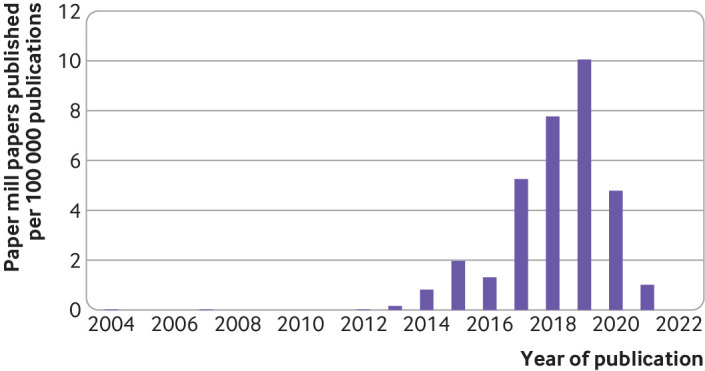

We identified 1182 retractions of paper mill papers from the Retraction Watch database that fulfilled the predefined inclusion criteria. During the study period, 58 278 163 papers were published and 33 741 were retracted for any reason, including being a paper mill product; a rate of 57.9 retractions per 100 000 publications. Figure 1 shows the number of paper mill papers published per year (and then retracted) with respect to the total number of papers published in each year. The year of the first publication of an identified paper mill paper was 2004, and the first retraction for this reason took place in 2016.

Fig 1.

Proportion, per 100 000, of paper mill papers published and then retracted per year with respect to total publications

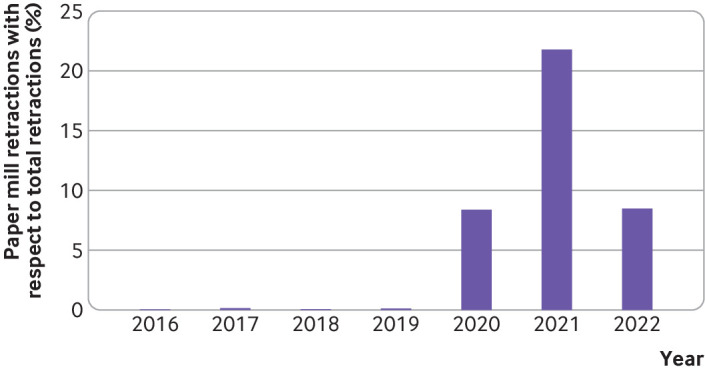

The proportion of paper mill papers published per year in the scientific literature has increased, from 0.04 per 100 000 in 2004 to its peak of 10.6 per 100 000 publications in 2019 (fig 1). After 2020, the number of these papers decreased in comparison with the total number of papers published. The proportion of paper mill retractions to all-cause retractions was low until 2021, the year in which paper mill retractions accounted for 772 (21.8%) of the 3544 retractions (fig 2).

Fig 2.

Percentage of paper mill retractions with respect to total retractions

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of retracted paper mill papers. Just over half of these papers had four to six authors; almost all authors of paper mill retractions came from Chinese institutions, followed by far fewer authors from Indian institutions; and more than three quarters of papers had a first author who was affiliated with a hospital. The papers were mainly published in journals of the second Journal Citation Reports quartile and were mainly asigned to the Journal Citation Reports category of pharmacology and pharmacy.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of papers retracted for originatng from paper mills.

| Variable | No (%) of papers (n=1182) |

| No of authors: | |

| 1-3 | 315 (26.7) |

| 4-6 | 602 (50.9) |

| >6 | 265 (22.4) |

| Authors’ country: | |

| China | 1144 (96.8) |

| India | 17 (1.4) |

| China and USA | 6 (0.5) |

| China and Germany | 2 (0.2) |

| Rest of the world | 13 (1.1) |

| First author’s affiliation: | |

| Hospital | 909 (76.9) |

| University | 176 (14.9) |

| Hospital and University | 66 (5.6) |

| Research centre | 11 (0.9) |

| Other | 20 (1.7) |

| JCR quartile: | |

| Q1 | 350 (29.6) |

| Q2 | 529 (44.8) |

| Q3 | 248 (21.0) |

| Q4 | 25 (2.1) |

| No IF | 30 (2.5) |

| JCR category: | |

| Pharmacology and pharmacy | 265 (22.4) |

| Oncology | 162 (13.7) |

| Biochemistry and molecular biology | 145 (12.3) |

| Education, scientific disciplines | 122 (10.3) |

| Medicine, research, and experimental | 103 (8.7) |

| Other | 356 (30.1) |

| Not indexed in JCR | 29 (2.5) |

Q=quartile of journal in which the paper was published; JCR=Journal Citation Reports; IF=impact factor.

Of the 1182 papers, 609 (51.5%) included a funding statement, and of these, 387 (63.5%) reported to have received external funding. Furthermore, 984 (83.2%) of papers included a declaration of the authors’ competing interests.

Fifteen scientific journals published a total of 812 (68.7%) of all 1182 papers retracted for being paper mill papers, and 166 (14.0%) were published in one journal, the European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. Of these, all journals appear to be non-predatory journals. Of all journals (n=99), 61 (61.6%) were open access journals (table 2): the highest number of papers published belonging to the Wiley publishing group and then Verduci Editore (table 3). Supplementary tables 1 and 2 include information of all journals and publisher houses.

Table 2.

The fifteen journals with the largest number of papers retracted for originating from paper mills, according to their Journal Citation Reports quartile and whether or not they are open access

| Journal | Journal Citation Reports quartile | Open access | No (%) of papers retracted for originating from paper mills (n=1182) |

|---|---|---|---|

| European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences | 2 | Yes | 166 (14.0) |

| Journal of Cellular Biochemistry | 1 | No | 134 (11.3) |

| International Journal of Electrical Engineering and Education | 1 | No | 122 (10.3) |

| RSC Advances | 2 | Yes | 68 (5.8) |

| Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy | 1 | Yes | 50 (4.2) |

| Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry | 1 | Yes | 49 (4.2) |

| Molecular Medicine Reports | 2 | Yes | 42 (3.6) |

| Artificial Cells, Nanomedicine, and Biotechnology | 1 | Yes | 40 (3.4) |

| Oncology Reports | 3 | Yes | 40 (3.4) |

| Journal of Cellular Physiology | 1 | No | 37 (3.1) |

| Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine | 3 | Yes | 34 (2.9) |

| OncoTargets and Therapy | 2 | Yes | 30 (2.5) |

| Bioscience Reports | 3 | Yes | 24 (2.0) |

| Cancer Management and Research | 3 | Yes | 22 (1.9) |

| Anatomical Record: Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology | 3 | No | 21 (1.8) |

| Other journals | NA | NA | 303 (25.6) |

NA=not available.

Table 3.

Publishing houses of the journals in which papers retracted for originating from paper mills were published

| Publishing house | No (%) of papers retracted for originating from paper mills (n=1182) |

|---|---|

| Wiley | 205 (17.3) |

| Verduci Editore | 166 (14.0) |

| SAGE Publications | 153 (12.9) |

| Spandidos | 152 (12.9) |

| Elsevier | 93 (7.9) |

| Royal Society of Chemistry | 70 (5.9) |

| Taylor and Francis | 56 (54) |

| Taylor and Francis-Dove Press | 54 (4.6) |

| Cellular Physiol Biochem Press | 49 (4.2) |

| Portland Press | 24 (2.0) |

| Mary Ann Liebert | 21 (1.8) |

| Springer | 21 (1.8) |

| Other publishing houses | 118 (10.0) |

The time elapsed between the manuscript’s submission to the journal and its publication varied according to journal quartile (table 4), from a median of 115 days (interquartile range 80-144), among journals of the first quartile, 128 (82-189) for journals in the second quartile, 163 (119-288) for those in the third quartile, and 332 (189-447) in fourth quartile journals. Likewise, the time between publication and retraction varied; shorter times were noted in journals of the first and second quartiles, and longer times in journals of the third and fourth quartiles and those with no impact factor.

Table 4.

Time elapsed between publication and retraction of papers retracted for originating from paper mills, both overall and by quartile of journal in which they were published. Data are median (interquartile range)

| Process interval | Overall time elapsed | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | No IF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Submission to publication (in days)* | 140 (93-217) |

115 (80-144) |

128 (82-189) |

163 (119-288) |

332 (189-447) |

225 (158-244) |

| Publication to retraction (in days)† | 891 (0-3229) |

829 (223-1933) |

792 (0-3121) |

1350 (181-2707) |

1564 (676-2130) |

907 (0-2234) |

IF=Impact factor; IQR=interquartile range; Q=quartile of Journal Citation Reports.

Missing values=659.

Missing values=2.

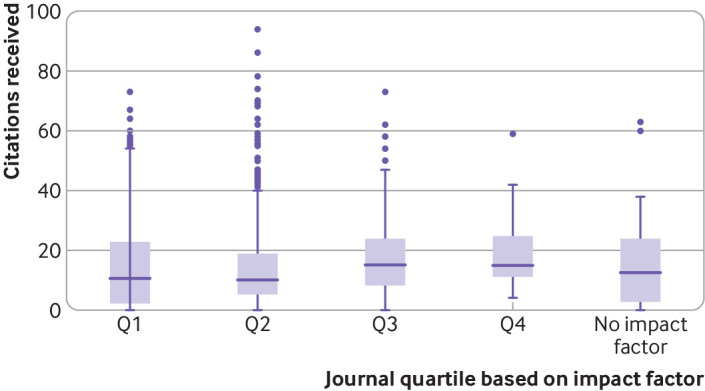

While 1086 (93.8%) of retracted paper mill papers received at least one citation, papers published in third and fourth quartile journals received a higher number of citations (fig 3). The median number of citations received by retracted paper mill papers from the date of publication was 11 (interquartile range 5-22), with the total ranging from 0 to 131 citations.

Fig 3.

Citations received by papers retracted for originating from paper mills, by quartile of journal in which they were published based on the impact factor. 24 values were missing. The box represents the interquartile range of the variable, the horizontal line inside the box indicates the median, the lower whisker indicates the lowest value excluding the outliers and the upper whisker indicates the highest value excluding the outliers. The circles represent the outliers of the variables

Discussion

Principal findings

Our cross sectional analysis of all papers retracted for originating from paper mills until June 2022, identified from the Retraction Watch database, suggests that these paper mill retractions are increasing in frequency. Nearly all authors of these papers came from China and were predominantly affiliated with hospitals. The median time for retraction of a paper mill paper was close to two years and increased with the ranking of the journal in which it was published, so that the higher the Journal Citation Reports impact factor, the shorter the period until retraction. These papers affect legitimate journals and does not seem to be exclusive to predatory journals. Furthermore, this study showed the impact and visibility of these retracted papers because some were highly cited, with the potential consequences that this entails. To our knowledge, this is the first study to analyse the growing phenomenon of paper mill retractions and their characteristics.

Our findings suggest that the publication of paper mill papers increased between 2017 and 2019, when about 5 to 10 were published and eventually retracted for this reason per 100 000 publications. In 2020, the number of identified paper mill papers published in the scientific literature fell sharply. This decrease may have occurred for a number of reasons. Firstly, papers published between 2020 and 2022 that might eventually be identified for retraction have not yet been identified or retracted. Retraction of a paper takes a long time, and more retractions will possibly appear in the future. Secondly, as a result of investigations initiated in early 2020 by a number of editors and researchers,12 the scientific community have become aware of the problem, and guidelines have been published to help editors identify such papers.4 Even though these guidelines do not enable a paper mill paper to be unequivocally recognised, they do make screening and identification of papers originating fom paper mills possible. Hence, numbers might be smaller than would have been because scientific journals have improved methods for their identication during editorial review and peer review, thereby preventing their publication. Thirdly, the increased attention to this type of fraud might also have deterred authors from engaging the services of paper mills, because of the consequences of scientific fraud, especially in some countries such as China.13 Then again, an increased exposure could have caused paper mill organisations to change their mode of operation, thus hindering detection.14

Although this issue is relatively new, particularly in America and Europe, for some years now the use of these types of organisations has been widespread in other countries, such as China.10 15 China encouraged its researchers to publish papers in return for money and career promotions.16 Furthermore, medical students at Chinese universities are required to produce a scientific paper in order to graduate.15 In fact, these organisations openly advertise their services on the Internet and maintain a presence on university campuses, not only in China but also in other countries, such as Russia.8 15

Perhaps unsurprisingly, most papers retracted for being paper mill papers come from that same country. These results are in line with the findings of other researchers and editors of scientific journals, although paper mill papers have been reported in other countries, such as Iran or Russia.8 12 17 The activity of the largest paper mill organisation in Russia named International Publisher has recently been acknowledged.8 10 Although this paper mill has published approximately 1000 papers, its own website announces that more than 5000 authors have bought the coauthorship of at least one paper.8

Also, we note that most authors of identified paper mill papers were hospital affiliated, which is consistent with previous research.15 The main reason for this might be that Chinese doctors are not affiliated with medical schools, but with hospitals. Of note, pressure to publish is greater in biomedical sciences than other specialties and publications are usually needed to get a university degree or a promotion in China.15

Most paper mill papers were published in pharmacy and clinical medicine journals, but many of them were published in basic science journals as well, such as cellular and molecular biology or biochemistry. Therefore, this problem not only affects clinical medicine areas. This research has not focused in analyzing specifically if paper mill papers are published more frequently on clinical medicine topics or basic research. We are of the opinion that this aspect should be further analysed. According to our results, no major variations over time have been observed in the topics covered by the paper mill papers so far. However, the latest COPE report indicates that this pattern could change, for example in topic areas or types of journals, over time.18

The main problem which paper mill papers pose for editors and reviewers of scientific journals is the difficulty of identifying them through the peer review process because the papers appear to be legitimate. Analysis of images in a manuscript has been identified as one of the possible strategies for detecting paper mill papers because most images tend to be manipulated or duplicated, or both.14 Although different softwares are capable of detecting image manipulation, paper mill papers often use duplicated images (or stock images)5 19 because they are more difficult to detect than manipulated ones. At present, no software is capable of detecting image duplication in a reliable way, thus leaving this task to editors and reviewers. That said, however, not all papers contain images that allow for scrutiny. Another strategy for screening questionable papers is the Problematic Paper Screener software. This software identifies so-called “tortured phrases,”—that is, unusual phrases instead of established ones, which might be an indicator of suspected scientific misconduct.20 Also, COPE has published a list of common indicators for paper mill papers that could serve as a screening tool for suspicious articles.18

With the aim of preventing and detecting scientific misconduct, some countries already have offices and specific bodies that address aspects relating to scientific integrity, but many others do not have structures of this type.21 Countries that have no body or policies governing scientific misconduct incur a higher risk of producing fraudulent papers.22 Countries such as Denmark, Sweden, and China, have passed laws against scientific fraud. Ironically, China has the most severe penalties for research fraud. The paucity of consequences that scientific misconduct has historically had in this country might have played an important role in the increase in unethical behaviour, including the use of paper mills.15 In 2018, after a number of scandals in China, the law against scientific fraud was strengthened by imposing sanctions that go beyond the purely academic and occupational sphere.23 This tougher approach appears to have started yielding results and, in December 2021, more than 300 researchers were reportedly penalised for scientific misconduct. Among other things, the penalties included revocation of academic degrees and cancellation of promotions.24 Because practically all paper mill papers come from China, these recent penalties policy might have contributed to the reduction in the number of paper mills since 2020.

Strengths and limitations

This study had limitations. Retractions of paper mill papers continue over time. Because of this, our investigation will need to be updated over time as the conclusions could well vary as the list of retractions grows. The characteristics of retracted and non-retracted paper mill papers can differ, which could explain why some papers were identified but not others, although all represent fraudulent science. Another limitation was the difficulty in assigning the cause of retraction in some cases, hence misclassification is a risk. In this study, we have included formally retracted paper mill papers, not taking into account suspicious papers (ie, those from the list elaborated by EB and others) and this might be a limitation of the present research. However, the inclusion of papers not formally retracted might incur in a risk of misclassification of those papers if they are not finally retracted as paper mill products. A limitation regarding the citation analysis is that citations before and after retraction have not been differentiated in this study and this issue should be considered in future research.

The main strength of this study was the use of the Retraction Watch database to identify retracted paper mill papers because this source is the main database on retractions and should currently be considered as the gold standard for aggregated information on retracted articles. The Retraction Watch database has three times the coverage of PubMed and five times the coverage of CrossRef (Retraction Watch, personal communication, 2022). Taking this into account, we consider that the number of missing retractions should be minimal.

Conclusions

The paper mill papers that we have identified as retracted to date possibly represent only a small number of paper mill papers in total because potentially thousands of these papers could have been published in the scientific literature and not yet identified nor retracted. Some editors of international scientific journals have begun to systematically identify and retract paper mill papers, which has led to mass retractions.25 26 The rise of paper mills is a new ethical problem in research and, more specifically, in publication ethics. Not only does this issue entail the sale of authorship, but these types of papers have also been observed to contain fabricated and manipulated data and images, thus disseminating false results in scientific literature. Efforts must be increased to prevent the use of these paper mill organisations, beginning with improved education in ethics and scientific integrity for editorial committees of scientific journals, students, and researchers.

What is already know on this topic

Evidence regarding paper mills organisations and articles produced by them is scarce

Information is needed about the characteristics of paper mill articles to identify and retract them, thus allowing the scientific literature to be corrected

What this study adds

This study analyses the evolution of paper mill papers, their characteristics, and their visibility in the scientific community

Retractions of paper mill papers are increasing in frequency and some of them are of highly cited papers, with the potential consequences that this entails

Acknowledgments

We thank Retraction Watch for making their data publicly available and Ivan Oransky and Alison Abritis for their constructive comments on the manuscript.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: Online appendix

Contributors: CCP was responsible for conceptualisation, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, and original draft preparation. ARR was responsible for conceptualisation, methodology, review, editing, and supervision. JSR was responsible for methodology, review, and editing. DSE was responsible for methodology, review, and editing. EF was responsible for methodology, review, and editing. MPR was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, review, and editing. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This work is part of the research conducting to the PhD degree of CC-P, who has received a PFIS (Contrato Predoctoral de Formación en Investigación en Salud) fellowship reference number FI21/00149 from the Health Institute Carlos III. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at https://www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: JSR receives research support through Yale University from Johnson and Johnson to develop methods of clinical trial data sharing, from the Medical Device Innovation Consortium as part of the National Evaluation System for Health Technology, the Food and Drug Administration for the Yale-Mayo Clinic Center for Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation program (U01FD005938), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HS022882), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01HS025164, R01HL144644), and from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation to establish the Good Pharma Scorecard at Bioethics International. JSR is also an expert witness at the request of Relator's attorneys, the Greene Law Firm, in a qui tam suit alleging violations of the False Claims Act and Anti-Kickback Statute against Biogen Inc. DSE serves as an expert witness in asbestos, talc, opioid, and concussion litigation at the request of injured people. No other authors declared any potential competing interests.

The lead author affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: We plan to disseminate our findings in public communities. Inmediately after publication we will launch a press release with the help of the press office of our University, and we expect that these findings will be published in mass media including newspapers and radio interviews. We will also use social networks such as Twitter and Linkedin and also communicate our results to Spanish Scientific Societies. Advocacy networks with interest in research integrity will also be contacted.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Ethical approval

Because this study used publicly available materials and did not involve humans, ethics committee approval was not required.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Retraction Watch. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under contract license for this study.

References

- 1. Campos-Varela I, Ruano-Raviña A. Misconduct as the main cause for retraction. A descriptive study of retracted publications and their authors. Gac Sanit 2019;33:356-60. 10.1016/j.gaceta.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fang FC, Steen RG, Casadevall A. Misconduct accounts for the majority of retracted scientific publications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:17028-33. 10.1073/pnas.1212247109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Recommendations for the conduct, reporting, editing and publication of scholarly work in medical journals. 2018. www.equator-network.org. [PubMed]

- 4.COPE Forum. 4 September 2020: paper mills. COPE: Committee on Publication Ethics.. https://publicationethics.org/resources/forum-discussions/publishing-manipulation-paper-mills

- 5. Rivera H, Teixeira da Silva JA. Retractions, fake peer reviews, and paper mills. J Korean Med Sci 2021;36:e165. 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e165 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34155837/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Christopher J. The raw truth about paper mills. FEBS Lett 2021;595:1751-7. 10.1002/1873-3468.14143 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/1873-3468.14143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang W, Pan Y. The gray industry chain of article writing business: starting at 2,000 and up to 150 000 for an SCI-indexed article. China News 2015 Sep 17. https://www.chinanews.com.cn/gn/2015/09-17/7530105.shtml.

- 8.Abalkina A. Publication and collaboration anomalies in academic papers originating from a paper mill: evidence from Russia. 2021. https://arxiv.org/abs/2112.13322

- 9.Retraction Watch. The Retraction Watch Database. New York: The Center for Scientific Integrity; 2018. www.retractiondatabase.org

- 10.Retraction Watch. Revealed: The inner workings of a paper mill – retraction watch. https://retractionwatch.com/2021/12/20/revealed-the-inner-workings-of-a-paper-mill/

- 11.Science Integrity Digest. The Tadpole Paper Mill. https://scienceintegritydigest.com/2020/02/21/the-tadpole-paper-mill/

- 12. Else H, Van Noorden R. The fight against fake-paper factories that churn out sham science. Nature 2021;591:516-9. 10.1038/d41586-021-00733-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cyranoski D. China introduces ‘social’ punishments for scientific misconduct. Nature 2018;564:312. 10.1038/d41586-018-07740-z https://click.endnote.com/viewer?doi=10.1038%2Fd41586-018-07740-z&token=WzM1NTE0MjMsIjEwLjEwMzgvZDQxNTg2LTAxOC0wNzc0MC16Il0.vcvos_Aby5lPiwGn-bv7WYAWwyE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Byrne JA, Christopher J. Digital magic, or the dark arts of the 21st century-how can journals and peer reviewers detect manuscripts and publications from paper mills?. FEBS Lett 2020;594:583-9. 10.1002/1873-3468.13747 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32067229/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu X, Chen X. Journal retractions some unique features of research misconduct in China. J Sch Publ 2018;49:305-19 10.3138/jsp.49.3.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Quan W, Chen B, Shu F. Publish or impoverish: An investigation of the monetary reward system of science in China (1999-2016). Aslib J Inf Manag 2017;69:486-502 10.1108/AJIM-01-2017-0014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stone R. A shady market in scientific papers mars Iran’s rise in science. Science. 2016.https://www.science.org/content/article/shady-market-scientific-papers-mars-iran-s-rise-science

- 18.COPE; STM. Paper mills research report with recommendations. 10.24318/jtbG8IHL [DOI]

- 19. Heck S, Bianchini F, Souren NY, Wilhelm C, Ohl Y, Plass C. Fake data, paper mills, and their authors: The International Journal of Cancer reacts to this threat to scientific integrity. Int J Cancer 2021;149:492-3. 10.1002/ijc.33604 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ijc.33604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cabanac G, Labbé C, Magazinov A. Tortured phrases: a dubious writing style emerging in science. Evidence of critical issues affecting established journals. 2021. https://arxiv.org/abs/2107.06751

- 21.Candal-Pedreira C, Ruano-Ravina A, Pérez-Ríos M. Should the European Union have an office of research integrity?. Eur J Intern Med; 2021. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34362610/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22. Fanelli D, Costas R, Larivière V. Misconduct Policies, Academic Culture and Career Stage, Not Gender or Pressures to Publish, Affect Scientific Integrity. PLoS One 2015;10:e0127556. 10.1371/journal.pone.0127556 https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0127556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nature . China sets a strong example on how to address scientific fraud editorial. Nature 2018;558:162. 10.1038/d41586-018-05417-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China. Notice from the Ministry of Science and Technology on the recent investigation and handling of thesis falsification. https://www.most.gov.cn/zxgz/kycxjs/kycxgzdt/202112/t20211201_178285.html

- 25.Retraction Watch. Publisher retracts nearly 80 articles over three days. https://retractionwatch.com/2021/11/14/publisher-retracts-nearly-80-articles-over-three-days/

- 26.Retraction Watch. Journal retracts 122 papers at once.https://retractionwatch.com/2021/12/15/journal-retracts-122-papers-at-once/#more-123768

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Online appendix

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Retraction Watch. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under contract license for this study.