Abstract

BACKGROUND

Telemedicine uses technology to deliver medical care remotely and has been shown to provide similar patient satisfaction and care outcomes compared with in-person visits.

OBJECTIVE

This study aimed to assess the gynecologic oncology patient telehealth experience.

STUDY DESIGN

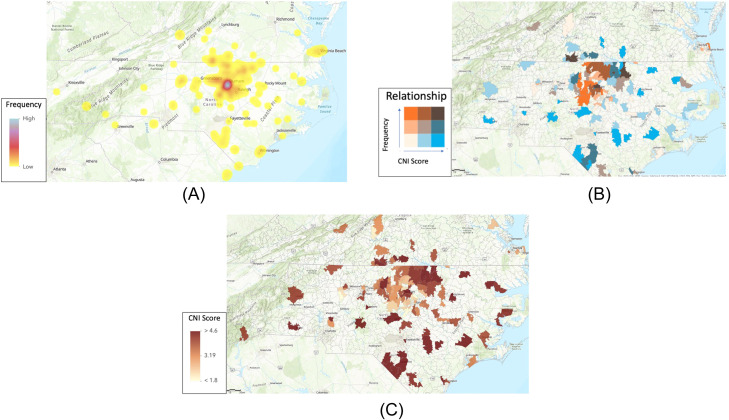

All patients receiving telehealth care between March 23, 2020, to May 14, 2020, from a single institution's gynecologic oncology division were offered postvisit surveys to assess satisfaction. Basic demographic and clinical data were collected and analyzed with descriptive statistics. Patient zip code data were correlated with Community Need Index scores and visualized using heat maps.

RESULTS

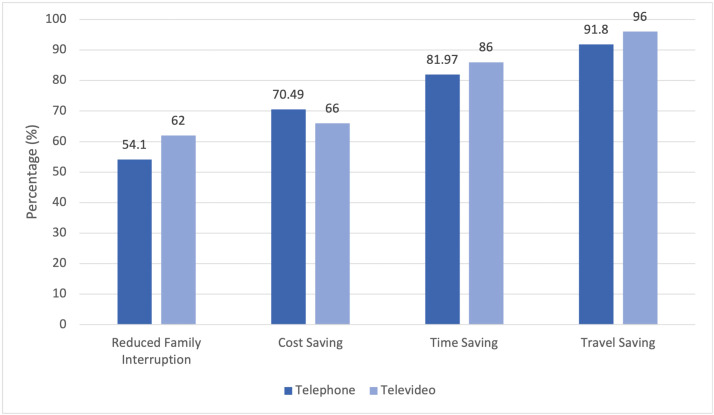

Of 286 telehealth visits, 112 postvisit surveys (39.2%) were collected. Survey responses demonstrated high patient satisfaction with responders agreeing that privacy was respected (97.3%), diagnosis and treatment options were adequately explained (92%), they could easily ask questions (97.3%), and they established a good rapport with their provider (96.4%). Additional benefits included reduced travel (92.9%), time (83.0%), cost (67.9%), and family interruption (57.1%). Among 11 patients receiving treatment on a clinical trial, 10 (90.9%) were able to continue on trial without disruption. Most responders (87.5%) preferred future visits to occur via telehealth or a mixture of telehealth and in-person visits. No difference in satisfaction was found among patients residing in zip codes associated with higher Community Need Index scores or increased distance from the institution.

CONCLUSION

The use of telemedicine in providing gynecologic oncology care was associated with high patient satisfaction and had the benefits of reduced time, cost, travel, and interruption to family time.

Key words: community needs, gynecologic oncology, healthcare access, heat map, patient satisfaction, telecommunication, telehealth, telemedicine, televideo

AJOG Global Reports at a Glance.

Why was this study conducted?

The assessment of practice patterns, management, and outcomes for gynecologic oncology patients accessing care through telemedicine is crucial for the optimization of these practices during the pandemic and beyond.

Key findings

The use of telemedicine in gynecologic oncology care was associated with self-reported benefits of reduced time, cost, travel, and interruption to family time. Most survey responders preferred future visits to occur via telehealth or a mixture of telehealth and in-person visits.

What does this add to what is known?

This study demonstrated high levels of patient-reported satisfaction and perceived benefits of telemedicine in providing gynecologic oncology care. No difference in satisfaction was found among survey responders residing in zip codes associated with higher Community Need Index scores or increased distances from the institution.

Introduction

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) outbreak a pandemic. This reshaped health systems worldwide because of the need to dedicate medical resources to patients diagnosed with COVID-19 and to comply with strategies that would halt disease transmission while protecting patients and physicians.1 Oncology patients were identified early as a population at high risk of developing a severe disease with COVID-19 based on the initial experience in China; the risks included higher infection rates, higher rates of admission to an intensive care unit, and elevated risk of death.2,3 For these patients, care was reprioritized: elective procedures were delayed or canceled; treatment plans were modified; in-person appointments were minimized; and telemedicine appointments were implemented.4

Telemedicine uses telecommunications and information technology to provide healthcare services to patients and share medical information remotely.5 This includes access to health assessment, diagnosis, intervention, consultation, supervision, and information from a distance.6 Telehealth services encompass live interaction via videoconferencing or phone, asynchronous communication or data transmission (eg, acquisition of medical reports, imaging, and video recordings to be interpreted at a later time), remote patient monitoring, and mobile health (eg, activity supported by cell phones, tablets, and wearable devices).1,7 Telemedicine represents an opportunity across medical specialties, including oncology, to maintain patient access to care and mitigate exposures to patients and providers in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic.8

Previous studies of telemedicine in primary care and specialty settings (cardiology, obstetrics, and dermatology) have demonstrated at least equivalent outcomes compared with in-person care, high levels of patient and provider satisfaction, and improved cost efficacy.7,9 A recent review of the use of telemedicine in high-risk obstetrics, for example, demonstrated improved access to care for patients living in medically underserved areas and highlighted the cost-effectiveness of home monitoring and remote surveillance via telemedicine.5

In oncology, telemedicine has been applied to provide remote genetics consultations, bundle interprofessional services and multidisciplinary care, allow remote supervision of chemotherapy delivery, and facilitate cancer clinical trial enrollment (eg, trial eligibility assessment, consent, participation, and follow-up, including symptom assessment and management).7 Previous studies of the use of telemedicine for providing oncologic care in rural areas have demonstrated greater alleviation of stress, positive effects on quality of life, and a greater sense of independence.10 Telemedicine-based, risk-stratified surveillance schemes for survivors of gynecologic cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic have also been suggested.11 However, varying practice patterns across institutions are currently in place. The assessment of practice patterns, management, and outcomes for gynecologic oncology patients accessing care through telemedicine is crucial for the optimization of these practices during the pandemic and beyond.

At the authors’ institution, gynecologic oncology patients were offered telemedicine for consults, follow-up, triage, and chemotherapy visits beginning in March 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study aimed to assess patient experiences with telehealth and its effect on clinical trials. Furthermore, this study aimed to assess relationships among zip code, Community Need Index (CNI) scores, and satisfaction with telehealth visits.

Materials and Methods

The institutional review board (IRB) at the authors’ institution determined this study qualified as quality improvement and deemed it exempt from full IRB approval (Pro00105160). Before the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine was not routinely offered to gynecologic oncology patients at the authors’ institution. By March 2020, a large proportion of patients had been transitioned to telehealth for their new consultations, chemotherapy visits, surveillance visits, postoperative visits, and clinical trial visits. The authors of this study began this quality improvement study to assess outcomes of care after telehealth visits, including patient perceptions and satisfaction, management decisions, and management of patients on clinical trials. This included creating a database for tracking patient demographics and clinical information of interest. In addition, patients were voluntarily surveyed after each telehealth encounter to assess patient satisfaction and perceptions of the care they received. Postvisit surveys were conducted by telephone or, if no phone response was obtained, via electronically e-mailed surveys. All patients seen within the gynecologic oncology division from March 23, 2020, to May 14, 2020, were screened. The survey tool was adapted from a previous telehealth study conducted on radiation oncology patients.9 Satisfaction was scored using a 5-point Likert scale.

Basic patient demographic information, including age, race, ethnicity, and home zip code, were collected. Clinical data collected included type of visit (new consult, surveillance, chemotherapy visit, postoperative visit, problem visit, etc.), cancer diagnosis, type of clinical data reviewed (laboratory values and imaging studies), and type of follow-up. Patient zip code data were correlated with CNI scores publicly accessible via the Internet (cni.chw-interactive.org). CNI scores are based on demographic and economic statistics and are linked to variations in healthcare needs; the score ranges from 1.0 to 5.0, where a score of 1.0 indicates the least need and 5.0 indicates the greatest need (the average score in the United States is 3.0).12 Esri ArcGIS Online mapping and spatial analytics software were used to layer the patient zip code and CNI score data onto publicly available geographic and zip code data for North Carolina and Virginia; the pattern analysis feature allowed visualization of these data in heat map formats (Esri, Redlands, CA).

Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap; Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) tools hosted at Duke University.14 REDCap is a secure, Web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing (1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry, (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures, (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages, and (4) procedures for importing data from external sources. We assessed the significance of differences using the Pearson chi-square test for categorical variables and the t test for continuous variables. All analyses were performed using Stata (version 15.1; StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

From March 23, 2020, to May 14, 2020, there were 286 telehealth visits within a single institution's gynecologic oncology clinic that included 247 unique patients. These encounters consisted of new consults (42, 15.0%), surveillance appointments (68, 23.8%), encounters for consideration of chemotherapy or treatment (104, 36.4%), postoperative visits (27, 9.4%), and acute problem visits (30, 10.5%) (Table 1). Most patients evaluated via telehealth had a gynecologic cancer diagnosis: 133 visits were for patients with ovarian, fallopian, or peritoneal cancer, and 78 visits were for patients with uterine cancer. Moreover, 11 patients were receiving treatment on a clinical trial and were also managed via telehealth services. Of these patients on trial, 10 (90.9%) were able to continue on trial during this period without disruption.

Table 1.

Patient clinicodemographics and encounter information (including ancillary management, tests reviewed, and follow-up scheduled) for patients with a telehealth visit during the COVID-19 pandemic, by responders vs nonresponders

| Total visits (N=286)Total patients (N=247) | Total (N=286) | Responders (n=112) | Nonresponders (n=174) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y), mean (SD) | 62.9 (13.9) | 65.5 (11.8) | 61.26 (14.9) | .012 |

| Race, n (%) | .019 | |||

| White | 159 (65.40) | 73 (75.26) | 86 (58.90) | |

| Black | 75 (30.90) | 20 (20.62) | 55 (37.67) | |

| Other or multiple | 9 (3.70) | 4 (4.12) | 5 (3.42) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | .782 | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (0.85) | 1 (1.05) | 1 (0.71) | |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 233 (99.10) | 94 (98.95) | 139 (99.29) | |

| Miles traveled, mean (SD) | — | 81.65 (101.5) | 74.81 (221.8) | .760 |

| CNI score, mean (SD) | — | 3.62 (0.898) | 3.72 (0.834) | .348 |

| Visit type, n (%) | .117 | |||

| New consult | 42 (14.70) | 16 (14.29) | 26 (14.94) | |

| Surveillance | 68 (23.78) | 20 (17.86) | 48 (27.59) | |

| Chemotherapy | 104 (36.36) | 49 (43.75) | 55 (31.61) | |

| Postoperative | 27 (9.44) | 13 (11.61) | 14 (8.05) | |

| Problem | 30 (10.49) | 11 (9.82) | 19 (10.92) | |

| Other | 15 (5.24) | 3 (2.68) | 12 (6.90) | |

| Cancer status, n (%) | .242 | |||

| No | 53 (18.53) | 17 (15.18) | 36 (20.69) | |

| Yes | 233 (81.47) | 95 (84.82) | 138 (79.31) | |

| Cancer site, n (%) | .504 | |||

| Ovarian, fallopian, or peritoneal | 133 (57.10) | 60 (62.50) | 73 (52.90) | |

| Uterine | 78 (33.50) | 28 (29.17) | 50 (36.23) | |

| Cervical | 14 (6.00) | 5 (5.21) | 9 (6.52) | |

| Vulvar or vaginal | 7 (3.00) | 3 (3.12) | 4 (2.90) | |

| Other | 2 (0.89) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.45) | |

| Chemotherapy managed, n (%) | .228 | |||

| No | 103 (44.60) | 37 (39.78) | 66 (47.83) | |

| Yes | 128 (55.40) | 56 (60.22) | 72 (52.17) | |

| Laboratory examinations reviewed, n (%) | .004 | |||

| No | 109 (38.11) | 31 (27.68) | 78 (44.83) | |

| Yes | 177 (61.90) | 81 (72.32) | 96 (55.17) | |

| Imaging reviewed, n (%) | .183 | |||

| No | 187 (65.38) | 68 (60.71) | 119 (68.39) | |

| Yes | 99 (34.62) | 44 (39.29) | 55 (31.61) | |

| Follow-up scheduled, n (%) | .556 | |||

| No | 56 (19.58) | 20 (17.86) | 36 (20.69) | |

| Yes | 230 (80.42) | 92 (82.14) | 138 (79.31) | |

| Follow-up type scheduled, n (%) | .650 | |||

| Clinic | 93 (40.43) | 40 (43.48) | 53 (38.41) | |

| Telehealth | 41 (17.83) | 18 (19.57) | 23 (16.67) | |

| Follow-up after surgery | 4 (1.74) | 1 (1.09) | 3 (2.17) | |

| Unspecified | 92 (40.00) | 33 (35.87) | 59 (42.75) | |

| Clinical trial | .020 | |||

| No | 275 (96.15) | 104 (92.86) | 171 (98.28) | |

| Yes | 11 (3.85) | 8 (7.14) | 3 (1.72) |

CNI, Community Need Index; SD, standard deviation.

Wong. Telemedicine and gynecologic oncology. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2022.

Patients who received telehealth appointments lived in 129 postcode areas with a mean distance of 77.6 miles (standard deviation [SD], 184.4) and in an area with an average CNI score of 3.67 (SD, 0.86). The largest proportion of patient zip codes was located within a 60-mile radius of the authors’ institution (Figure 1, A; blue dot). Patients residing in areas with higher CNI scores seem to live farther away from the institution (Figure 1, B; maroon). Patients with the most frequent visits reside in nearby zip codes with lower CNI scores (Figure 1, C; orange), and those with less frequent visits reside in farther zip codes with higher CNI scores (Figure 1, C; blue).

Figure 1.

Relationship maps of patient locations and community need index scores

A, Heat map of frequency of patients from each zip code. B, Choropleth map representing the average CNI score for each patient zip code. C, Relationship map demonstrating the frequency of patients coming from zip codes of increasing CNI score.

CNI, Community Need Index.

Wong. Telemedicine and gynecologic oncology. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2022.

Postvisit surveys yielded 112 responses obtained from 108 unique patients (response rate, 39.2%). Surveys were administered an average of 7 days after the telemedicine encounter (range, 0–18 days; SD, 4.57 days). Those who responded were more likely to be older (average age: 65.5 years for responders vs 61.3 years for nonresponders; P=.01) (Table 1). Moreover, responders were more likely to identify as White. Of the responses, 62 (55.4%) were from patients who had telephone visits, and 50 (44.6%) were from patients who had televideo visits. There was no statistical difference in distance from the institution or CNI score when comparing survey responders with nonresponders (distance: 81.7 vs 74.8 miles, P=.76; CNI score: 3.62 vs 3.72; P=.35), respectively (Table 1). Furthermore, there was no statistical difference in the type of visit between responders and nonresponders, with 81.5% of total visits related to an existing cancer diagnosis and 55% of total visits involving chemotherapy management (P=.24 and P=.23, respectively). There was no difference in response rates among patients with different types of gynecologic malignancy (P=.51). Most visits (62%) involved a provider who concurrently reviewed results from laboratory studies. Those who were married were more likely to have video visits (54.6% vs 31.1%; P=.015) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient factors of survey responders and survey results, by telephone vs video visit

| Variable | Total (N=112) | Telephone (n=62) | Televideo (n=50) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNI score of ≥4, n (%)a | .935 | |||

| No | 60 (53.60) | 33 (53.23) | 27 (54.00) | |

| Yes | 52 (46.40) | 29 (46.77) | 23 (46.00) | |

| Distance of ≥100 miles, n (%)a | .490 | |||

| No | 82 (73.20) | 47 (75.81) | 35 (70.00) | |

| Yes | 30 (26.80) | 15 (24.19) | 15 (30.00) | |

| Highest level of educationb | .026 | |||

| Primary school | 3 (2.68) | 3 (4.84) | 0 (0) | |

| High school or GED | 31 (27.68) | 21 (33.87) | 10 (20.00) | |

| Some college | 33 (29.46) | 21 (33.87) | 12 (24.00) | |

| 4-year college degree | 43 (38.39) | 16 (25.81) | 27 (54.00) | |

| No answer | 2 (1.79) | 1 (1.61) | 1 (2.00) | |

| Marital statusb | .015 | |||

| No | 45 (40.54) | 31 (50.80) | 14 (28.00) | |

| Yes | 66 (59.46) | 30 (49.20) | 36 (72.00) | |

| Baseline difficulty hearingb | .199 | |||

| No | 89 (79.46) | 52 (83.90) | 37 (74.00) | |

| Yes | 23 (20.54) | 10 (16.10) | 13 (26.00) | |

| I could hear the provider clearly | .263 | |||

| No | 1 (0.89) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.00) | |

| Yes | 111 (91.11) | 62 (100.00) | 49 (98.00) | |

| I felt like my privacy and confidentiality were respected | .274 | |||

| Strongly agree | 101 (90.18) | 59 (95.16) | 42 (84.00) | |

| Agree | 8 (7.14) | 3 (4.84) | 5 (10.00) | |

| Neutral | 1 (0.89) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.00) | |

| Disagree | 1 (0.89) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.00) | |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (0.89) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.00) | |

| I felt like I could ask questions and seek clarification openly and easily with my doctor or provider | .268 | |||

| Strongly agree | 103 (91.96) | 59 (95.16) | 44 (88.00) | |

| Agree | 6 (5.36) | 3 (4.84) | 3 (6.00) | |

| Neutral | — | — | — | |

| Disagree | 2 (1.79) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.00) | |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (0.89) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.00) | |

| I found it easy to establish rapport with my oncologist | .252 | |||

| Strongly agree | 102 (91.11) | 58 (93.55) | 44 (88.00) | |

| Agree | 6 (5.36) | 4 (6.45) | 2 (4.00) | |

| Neutral | 2 (1.79) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.00) | |

| Disagree | 1 (0.89) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.00) | |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (0.89) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.00) | |

| I felt like my diagnosis and treatment options were adequately explained to me | .120 | |||

| Strongly agree | 94 (83.93) | 53 (85.48) | 41 (82.00) | |

| Agree | 9 (8.04) | 7 (11.29) | 2 (4.00) | |

| Neutral | 5 (4.46) | 2 (3.23) | 3 (6.00) | |

| Disagree | 1 (0.89) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.00) | |

| Strongly disagree | 3 (2.68) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.00) | |

| Select all benefits that applied | ||||

| Reduced family interruption (4) | 64 (57.14) | 33 (54.10) | 31 (48.40) | .402 |

| Travel saving (3) | 104 (92.86) | 56 (91.80) | 48 (96.00) | .365 |

| Cost saving (1) | 76 (67.86) | 43 (70.49) | 33 (66.00) | .612 |

| Time saving (2) | 93 (83.04) | 50 (81.97) | 43 (86.00) | .566 |

| Preference for future visits | .223 | |||

| Mixture of telehealth and hospital or clinic visits | 83 (74.11) | 42 (67.74) | 41 (82.00) | |

| Telehealth through MyChart | 15 (13.39) | 10 (16.13) | 5 (10.00) | |

| Travel to hospital or clinic | 14 (12.50) | 10 (16.13) | 4 (8.00) |

CNI, Community Need Index; GED, General Education Diploma.

CNI and distance are based on patient zip code of residence

Self-reported patient demographics.Wong. Telemedicine and gynecologic oncology. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2022

Most survey participants (109, 97.3%) agreed or strongly agreed that their privacy was respected during the telemedicine visit, and 103 participants (92%) agreed or strongly agreed that their diagnosis and treatment options were adequately explained. Most participants (109, 97.3%) agreed that they could easily ask questions during their telehealth appointment, and 108 participants (96.4%) felt they established a good rapport with their provider via telecommunication appointments. Going forward, 83 participants (74.1%) indicated that they preferred a mixture of telehealth and in-person visits, 14 participants (12.5%) indicated that they preferred only in-person visits moving forward, and 15 participants (13.4%) indicated that they preferred only telehealth visits moving forward (Table 2). Additional perceived benefits of telemedicine are displayed in Figure 2, which include travel saving, time saving, and cost saving.

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients agreeing with perceived benefits of telemedicine visits

Patients were allowed to select all options they felt were applicable. These data are to be used for publication online only.

Wong. Telemedicine and gynecologic oncology. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2022.

There was no significant difference in satisfaction or perceived benefits for those who had telephone vs televideo visits. There was no significant difference in satisfaction with telehealth encounters for patients whose zip codes corresponded to increasing distance from the clinic or increasing CNI scores.

Discussion

Principle findings

Gynecologic oncology telehealth visits by phone or video were reported by participants to have several benefits, most frequently time saving and travel saving. High patient satisfaction was indicated by the strong (>90%) agreement among responders that privacy was respected, diagnosis and treatment options were adequately explained, questions were easily asked, and good rapport was established. Furthermore, high patient satisfaction was indicated by the large proportion (87.5%) of survey responders who indicated a preference for future visits to occur via telehealth or a mixture of telehealth and in-person visits. Continued participation in clinical trials was feasible, with most patients (90.9%) able to continue on trial without disruption during the study period. Of note, 1 patient on protocol experienced a treatment delay and initiated a treatment holiday for safety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, patient satisfaction and perceived benefits did not vary by distance from a clinic or increasing CNI scores; however, patients living in areas with higher CNI scores were noted to reside farther away from the institution and have a lower frequency of appointments, representing an opportunity to increase access to appointments with the use of telehealth.

Results

These data supported previous studies showing high levels of patient satisfaction with telehealth encounters.7,9,10 In particular, a recent descriptive analysis of telehealth visits in radiation oncology patients used a similar satisfaction questionnaire and had a response rate of 45.8%, with positive responses largely attributed to time saving and travel saving; patient preferences for future visits to occur by telehealth or a mixture of telehealth and in-person visits were also high at 54.7% and 34.9%, respectively.9 Another recent study evaluated the use of telemedicine in gynecologic oncology visits to improve accessibility for racial groups of varying Social Vulnerability Index.13 Compared with other studies, our study surveyed patients for perceived benefits and satisfaction with telehealth visits and used geocoding with CNI scores that account for income, cultural, education, insurance, and housing barriers.

Clinical and research implications

Overall, patient-reported experiences were largely positive. The care of patients in clinical trials was not compromised, although the data were limited in this small select group. The expansion of telehealth represents an opportunity to continue providing patient-centered gynecologic oncology care for patients in a manner that is time saving, travel saving, and cost saving, that maintains high levels of patient satisfaction, and that has the potential to improve access to healthcare.

Given that the study period took place in the first 2 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, a more longitudinal evaluation is recommended before the generalization of these results. In addition, reimbursement issues may represent a challenge to the implementation and should be further evaluated. Furthermore, drawbacks to telemedicine must be considered in discussing its implementation in clinical practice; for example, the inability to conduct physical examinations during visits may affect clinical outcomes and have not previously been evaluated in the gynecologic setting. Future studies on cost-effectiveness, provider attitudes, and clinical outcomes have been indicated.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study included that the demographic characteristics of patients seen are representative of the gynecologic oncology patient population at this institution. In addition, although CNI scores were not associated with the distance between the patient's home and the authors’ institution, the geographic maps provided a novel representation of these relationships. This facilitated a better understanding of how telehealth increases access to care for patients who would need to travel farther for care (in the absence of telemedicine options) or who come from areas with higher CNI scores.

The key limitation of the study was its descriptive nature, as it did not assess patient outcomes. Moreover, the study was conducted at a single institution with a response rate of 39.2%, further limiting any conclusions made. In addition, self-motivated bias and positive response bias may be present because of the nature of using voluntary surveys and administering them over the phone, respectively; these may have conflated the results demonstrating the benefits of telehealth. There were statistically significant differences between survey responders and nonresponders, with responders more likely to be White, older, and have received laboratory testing before the visit. Moreover, these factors may contribute to response biases and overestimate patient satisfaction. This study did not address the concern for the quality of care and care outcomes for gynecologic oncology patients given the inability to perform pelvic examinations with telehealth appointments. Moreover, reliable Internet access was not explicitly evaluated and could represent an important limiting factor in the widespread adoption of telehealth visits. Finally, this study did not assess provider attitudes and experiences with telehealth visits, especially given the lower reimbursement rates of these visits. These limitations warrant further evaluation.

Conclusion

The use of telemedicine to deliver gynecologic oncology care was associated with high levels of patient satisfaction and reported benefits, including saving time, decreasing travel, reducing cost, and limiting family interruption. Moreover, most patients were able to continue treatment on a clinical trial without interruption, although these data included a small select group of patients. Patients reported high levels of interest in using telemedicine or a mixture of telemedicine with in-person visits moving forward. No significant difference based on zip code distances and CNI scores was found. Although these results were positive and demonstrated the feasibility of telemedicine in gynecologic oncology care, further longitudinal evaluation at other institutions with different patient populations is warranted.

Footnotes

J.W. and R.G. contributed equally to this work.

R.A.P. has served on Myriad advisory boards. The remaining authors report no conflict of interest.

This study was accepted for presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology Virtual Annual Meeting, March 19–25, 2021.

This study received no funding. R.A.P. is supported by grants from 1K12 HD 103083-1 and the Emerson Collective.

Patient consent is not required because no personal information or detail is included in this study.

Cite this article as: Wong J, Gonzalez R, Albright B, et al. Telemedicine and gynecologic oncology: caring for patients remotely during a global pandemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2022;XX:x.ex–x.ex.

References

- 1.Novara G, Checcucci E, Crestani A, et al. Telehealth in urology: A systematic review of the literature. How much can telemedicine be useful during and after the COVID-19 pandemic? Eur Urol. 2020;78:786–811. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ortiz-Prado E, Simbaña-Rivera K, Gómez-Barreno L, et al. Clinical, molecular, and epidemiological characterization of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), a comprehensive literature review. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;98 doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2020.115094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinelli F, Garbi A. Change in practice in gynecologic oncology during the COVID-19 pandemic: a social media survey. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020;30:1101–1107. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2020-001585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whittington JR, Magann EF. Telemedicine in high-risk obstetrics. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2020;47:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2020.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kvedar J, Coye MJ, Everett W. Connected health: a review of technologies and strategies to improve patient care with telemedicine and telehealth. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:194–199. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sirintrapun SJ, Lopez AM. Telemedicine in cancer care. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:540–545. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_200141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aziz A, Zork N, Aubey JJ, et al. Telehealth for high-risk pregnancies in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37:800–808. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1712121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamilton E, Van Veldhuizen E, Brown A, Brennan S, Sabesan S. Telehealth in radiation oncology at the Townsville Cancer Centre: service evaluation and patient satisfaction. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2019;15:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ctro.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zimmerman BS, Seidman D, Berger N, et al. Patient perception of telehealth services for breast and gynecologic oncology care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a single center survey-based study. J Breast Cancer. 2020;23:542–552. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2020.23.e56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mancebo G, Solé-Sedeño JM, Membrive I, et al. Gynecologic cancer surveillance in the era of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2021;31:914–919. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2020-001942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.IBM Watson Health. 2020 Community Need Index: methodology and source notes. 2019. Available at: http://cni.dignityhealth.org/Watson-Health-2020-Community-Need-Index-Source-Notes.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2021.

- 13.McAlarnen LA, Tsaih SW, Aliani R, Simske NM, Hopp EE. Virtual visits among gynecologic oncology patients during the COVID-19 pandemic are accessible across the social vulnerability spectrum. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;162:4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]