Abstract

Background

Intensive cytotoxic chemotherapy for people with cancer can cause severe and prolonged cytopenia, especially neutropenia, a critical condition that is potentially life‐threatening. When manifested by fever and neutropenia, it is called febrile neutropenia (FN). Invasive fungal disease (IFD) is one of the serious aetiologies of chemotherapy‐induced FN. In pre‐emptive therapy, physicians only initiate antifungal therapy when an invasive fungal infection is detected by a diagnostic test. Compared to empirical antifungal therapy, pre‐emptive therapy may reduce the use of antifungal agents and associated adverse effects, but may increase mortality. The benefits and harms associated with the two treatment strategies have yet to be determined.

Objectives

To assess the relative efficacy, safety, and impact on antifungal agent use of pre‐emptive versus empirical antifungal therapy in people with cancer who have febrile neutropenia.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE Ovid, Embase Ovid, and ClinicalTrials.gov to October 2021.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared pre‐emptive antifungal therapy with empirical antifungal therapy for people with cancer.

Data collection and analysis

We identified 2257 records from the databases and handsearching. After removing duplicates, screening titles and abstracts, and reviewing full‐text reports, we included seven studies in the review. We evaluated the effects on all‐cause mortality, mortality ascribed to fungal infection, proportion of antifungal agent use (other than prophylactic use), duration of antifungal use (days), invasive fungal infection detection, and adverse effects for the comparison of pre‐emptive versus empirical antifungal therapy. We presented the overall certainty of the evidence for each outcome according to the GRADE approach.

Main results

This review includes 1480 participants from seven randomised controlled trials. Included studies only enroled participants at high risk of FN (e.g. people with haematological malignancy); none of them included participants at low risk (e.g. people with solid tumours).

Low‐certainty evidence suggests there may be little to no difference between pre‐emptive and empirical antifungal treatment for all‐cause mortality (risk ratio (RR) 0.97, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.72 to 1.30; absolute effect, reduced by 3/1000); and for mortality ascribed to fungal infection (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.89; absolute effect, reduced by 2/1000). Pre‐emptive therapy may decrease the proportion of antifungal agent used more than empirical therapy (other than prophylactic use; RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.05; absolute effect, reduced by 125/1000; very low‐certainty evidence). Pre‐emptive therapy may reduce the duration of antifungal use more than empirical treatment (mean difference (MD) ‐3.52 days, 95% CI ‐6.99 to ‐0.06, very low‐certainty evidence). Pre‐emptive therapy may increase invasive fungal infection detection compared to empirical treatment (RR 1.70, 95% CI 0.71 to 4.05; absolute effect, increased by 43/1000; very low‐certainty evidence). Although we were unable to pool adverse events in a meta‐analysis, there seemed to be no apparent difference in the frequency or severity of adverse events between groups.

Due to the nature of the intervention, none of the seven RCTs could blind participants and personnel related to performance bias. We identified considerable clinical and statistical heterogeneity, which reduced the certainty of the evidence for each outcome. However, the two mortality outcomes had less statistical heterogeneity than other outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

For people with cancer who are at high‐risk of febrile neutropenia, pre‐emptive antifungal therapy may reduce the duration and rate of use of antifungal agents compared to empirical therapy, without increasing over‐all and IFD‐related mortality; but the evidence regarding invasive fungal infection detection and adverse events was inconsistent and uncertain.

Keywords: Humans, Antifungal Agents, Antifungal Agents/adverse effects, Febrile Neutropenia, Febrile Neutropenia/chemically induced, Febrile Neutropenia/prevention & control, Invasive Fungal Infections, Invasive Fungal Infections/drug therapy, Invasive Fungal Infections/prevention & control, Neoplasms, Neoplasms/drug therapy, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Pre‐emptive versus empirical antifungal therapy in people with cancer who have febrile neutropenia

Intensive chemotherapy for people with cancer can cause severe and prolonged cytopenia (lower‐than‐normal number of blood cells), especially neutropenia (lower‐than‐normal white blood cells, which help to fight infection), a critical condition that is potentially life‐threatening. When a person has both fever and neutropenia, it is called febrile neutropenia (FN). Invasive fungal disease (IFD; an infection caused by a fungus) is one of the serious causes of chemotherapy‐induced FN.

There are two treatment strategies in this situation. In empirical antifungal therapy, an antifungal medicine is given when the doctor first suspects there is a fungal infection (e.g. person still has a fever after four to seven days of antibiotic therapy, or the doctor is still trying to pinpoint the cause of the fever). In pre‐emptive therapy, the doctor uses a series of laboratory screening tests to find what is causing the infection before starting the antifungal medicine.

Compared to empirical therapy, pre‐emptive therapy may reduce the use of antifungal medicines and the adverse effects they can cause, but may increase the number of deaths. The benefits and harms associated with the two treatment strategies have yet to be determined.

Who will be interested in this review? Healthcare professionals, including clinical oncologists; people with cancer and the people around them.

What question does this review aim to answer? This systematic review aimed to find and evaluate the evidence for the relative efficacy (how well they work); safety (the number and severity of side effects); and the impact of pre‐emptive versus empirical antifungal therapy on the use of antifungal medicines in people with cancer who have FN.

Which studies were included in the review? We searched electronic medical databases to find all relevant studies that included adults with cancer who had FN. To be included, the studies had to be randomised controlled trials (RCTs), which means the participants were divided at random (by chance alone), to receive either empirical or pre‐emptive antifungal medicine (last search October 2021). We included seven studies, involving 1480 people, which compared empirical and pre‐emptive antifungal treatment strategies.

What does the evidence from the review tell us? For people with cancer and febrile neutropenia, there may be little or no difference in the number of deaths between those receiving pre‐emptive and those receiving empirical antifungal therapy. Pre‐emptive therapy may increase the rate of identifying IFD, and reduce the duration and rate of use of antifungal medicines, but has not been shown to reduce adverse events. The certainty of the evidence ranged from very low to low; at best, our confidence in the effect estimate is limited.

What should happen next? Pre‐emptive therapy may be a promising treatment method for people with cancer who have FN. Since the trials reported different treatments, standardising treatment protocols will help to determine a more valid evaluation of the treatment effects.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Pre‐emptive antifungal therapy versus empirical antifungal therapy.

| Pre‐emptive antifungal therapy versus empirical antifungal therapy for febrile neutropenia in people with cancer | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with cancer who have febrile neutropenia Settings: intensive cytotoxic chemotherapy at hospital Intervention: pre‐emptive antifungal therapy Comparison: empirical antifungal therapy | ||||||

| Outcome | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk with empirical antifungal therapy | Corresponding risk with pre‐emptive antifungal therapy | |||||

| All‐cause mortality | 108 per 1000 | 105 per 1000 (78 to 141) | RR 0.97 (0.72 to 1.30) | 1459 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕◯◯ lowa |

‐ |

| Mortality ascribed to fungal infection | 29 per 1000 | 27 per 1000 (13 to 55) | RR 0.92 (0.45 to 1.89) | 1407 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕◯◯ lowa |

‐ |

| Proportion of antifungal agent use (other than prophylactic use) | 431 per 1000 | 306 per 1000 (202 to 452) | RR 0.71 (0.47 to 1.05) | 1480 (7 RCTs) | ⊕◯◯◯ very lowb |

‐ |

|

Duration of antifungal use (days) |

The mean duration of antifungal use ranged across control groups from 7 to 20 days |

The mean duration of antifungal use ranged across intervention groups from 4.5 to 13.8 days |

MD ‐3.52 (‐6.99 to ‐0.66) | 764 (3 RCTs) | ⊕◯◯◯ very lowb |

‐ |

| Invasive fungal infection detection | 60 per 1000 | 103 per 1000 (43 to 244) | RR 1.70 (0.71 to 4.05) | 1480 (7 RCTs) | ⊕◯◯◯ very lowb |

‐ |

| Adverse effects |

Hebart 2009 reported 39/152 (25.7%) cases of nephrotoxicity in the pre‐emptive therapy group, and 28/92 cases (30.4%) in the empirical therapy group. Morrissey 2013 reported 12/118 (10%) cases of hepatotoxicity in the pre‐emptive therapy group, and 21/122 (17%; P = 0.11) cases in the empirical therapy group; and 60/118 (51%) cases of nephrotoxicity in the pre‐emptive therapy group, and 52/122 (43%; P = 0.21) cases in the empirical therapy group. Cordonnier 2009 reported the mean decrease in creatinine clearance ± SD was larger in the empirical therapy group (‐8.7 ± 20.8) than in the pre‐emptive therapy group (‐5.8 ± 27.2). Severe adverse events occurred in similar proportions in the two groups. Yuan 2016 reported that 1/26 courses (3.8%) of antifungal treatment resulted in adverse events leading to discontinued treatment in the pre‐emptive therapy group, and 2/43 courses (4.7%) resulted in adverse events leading to discontinued treatment in the empirical therapy group (P = 0.874). |

1074 (4 RCTs) |

⊕◯◯◯ very lowc |

‐ | ||

| *The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the intervention group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; MD, mean difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aWe downgraded the certainty of the evidence by two levels. First, since there were no blinded studies, this could lead to considerable risk of bias; second, the clinical heterogeneity of the interventions was a critical factor of indirectness. bWe downgraded the certainty of the evidence by three levels. First, since there were no blinded studies, this could lead to considerable risk of bias; second, the clinical heterogeneity of the interventions was critical factor of indirectness; third, the results were inconsistent, marked with considerable heterogeneity (I2 =75% to 88%). cWe downgraded the certainty of the evidence by three levels. First, since there were no blinded studies, this could lead to considerable risk of bias; second, the clinical heterogeneity of the interventions was critical factor of indirectness; third, meta analysis was not performed.

Background

Description of the condition

Intensive cytotoxic chemotherapy for people with cancer can cause severe and prolonged cytopenia, especially neutropenia, a critical condition that is potentially life‐threatening (Smith 2015). When it is manifested by fever and neutropenia, it is called febrile neutropenia (FN). The fever is defined as a single oral temperature reading that is above 38.3 °C (101 °F), or a temperature above 38.0 °C (100.4 °F) that is sustained for at least one hour. Neutropenia is defined as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 500 cells/mm³ or less, or an ANC that is expected to decrease to less than 500 cells/mm³ during the next 48 hours (Freifeld 2011). Incidence rates of chemotherapy‐induced FN are 10% to 50% in people with solid tumours, and more than 80% with haematological malignancies (Al‐Tawfiq 2019; Klastersky 2004).

Invasive fungal disease (IFD) is one of the serious aetiologies of chemotherapy‐induced FN. It is challenging to diagnose IFD early in the course of FN, due to the low sensitivity and specificity of clinical symptoms (e.g. fever, cough, haemoptysis, maculopapular eruptions, nodules, erythema), and microbiological and radiological diagnostic tests (Maddy 2019). Treatment outcomes can potentially result in severe morbidity and mortality when the initiation of therapy is delayed. One autopsy study revealed that 69% of people with a history of prolonged FN had evidence of invasive fungal infections (Cho 1979). A more recent report suggested that the incidence rate of IFD, even in people at a high risk, was considered to be 10% or lower; there was considerable variation in the incidence rate among different cancer types (e.g. leukaemia, allogeneic stem cell transplant, etc), countries, and cancer hospitals (Maertens 2018).

To reduce the morbidity and mortality from IFD, researchers have investigated several antifungal drug strategies. An antifungal treatment strategy is often initiated by giving antifungal drugs prophylactically during chemotherapy. Numerous clinical trials have investigated a prophylactic approach and observed robust efficacy, reducing the risk of IFD and fungal infection‐related mortality (Bow 2002; Glasmacher 2003; Robenshtok 2007). Accordingly, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines recommend antifungal prophylactic drugs (A‐1 recommendation) for people with high‐risk FN (Freifeld 2011).

Alternative antifungal treatment should be considered when fever persists or recurs despite the use of empirical antimicrobial therapy and antifungal prophylaxis. Empirical antifungal therapy refers to the administration of an antifungal agent at the first clinical suspicion of fungal infection (e.g. persistent fever after four to seven days of antibiotic therapy, or in the absence of a definitive diagnosis (Chen 2017)). In previous clinical trials, empirical therapy showed favourable survival outcomes (EORTC 1989; Pizzo 1982). This therapy is also strongly recommended (A‐1 recommendation) in the IDSA guidelines (Freifeld 2011). However, the practice of empirical administration of antifungal drugs leads to several concerns: possible overuse of antifungal agents, emergence of antifungal resistance, undesirable drug interaction, and adverse effects (i.e. nephrotoxicity and hepatotoxicity (Maertens 2012)).

To combat these concerns, researchers have developed another approach, called pre‐emptive or presumptive antifungal therapy. Pre‐emptive therapy is generally referred as the treatment that uses antifungal agents only in cases when fungal infection is detected by diagnostic tests, such as imaging tests (e.g. chest X‐ray, chest and sinus computed tomography (CT) scan), rapid sensitive microbiology assays (e.g. β‐D‐glucan, galactomannan antigen, serum Candida spp. or Aspergillus spp. polymerase chain reaction (PCR)), or both (Fung 2015). According to the IDSA guidelines, pre‐emptive antifungal management is an acceptable alternative to empirical antifungal therapy in a subset of people with high‐risk neutropenia (Freifeld 2011).

To date, there has been no examination of the difference between empirical and pre‐emptive administration of antifungal drugs for efficacy, safety, and impact on clinical resource use. The development of novel antifungal prophylactic agents, and the selection of antifungal prophylactic agents also confound efforts to determine the risks (harms) and benefits between the two treatment strategies.

Description of the intervention

Pre‐emptive therapy begins with serial screening, using rapid sensitive microbiology assays, to detect the presence of a putative pathogen or early subclinical infection. Physicians may also use an imaging test to support a diagnosis. Considering that a single diagnostic approach yields less sensitivity, a combination of microbiology assay and imaging studies may be promising for the early diagnosis of fungal infection (Asano‐Mori 2008; Escuissato 2005; Marr 2005). The combination of these tests leads to the existence of various pre‐emptive therapy protocols. When these tests are positive, antifungal therapy is initiated to avoid progression to an invasive disease.

How the intervention might work

In pre‐emptive therapy, physicians only initiate antifungal therapy when an invasive fungal infection is detected by a diagnostic test. Accordingly, pre‐emptive treatment is expected to decrease the use of antifungal drugs, the emergence of antifungal resistance, undesirable drug interactions, and adverse effects (Fung 2015). However, if the initiation of pre‐emptive treatment is delayed, it may lead to life‐threatening situations compared with empirical therapy.

Why it is important to do this review

Compared to empirical therapy, pre‐emptive therapy may reduce the use of antifungal agents and associated adverse effects, but may increase mortality. The benefits and harms associated with the two treatment strategies have yet to be determined. This systematic review aimed to provide a body of evidence regarding the relative efficacy, safety, and impact of antifungal agent use of pre‐emptive versus empirical antifungal therapy in people with cancer who have FN.

Objectives

To assess the relative efficacy, safety, and impact of antifungal agent use of pre‐emptive versus empirical antifungal therapy in people with cancer who have febrile neutropenia.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We only included studies with a randomised controlled trial (RCT) design that compared pre‐emptive antifungal therapy with empirical antifungal therapy for people with cancer, in which participants were prospectively identified. Our eligibility criteria included cluster‐randomised and cross‐over trials. We did not include quasi‐randomised (i.e. using a method of allocation that is not truly random) or non‐randomised comparative studies.

Types of participants

We included studies with adults, 18 years or older, with cancer, who had febrile neutropenia (FN) as a result of chemotherapy or bone marrow transplantation. We did not restrict participants for gender, ethnicity, underlying malignancies (e.g. solid tumours, haematological malignancies, or haematopoietic stem cell recipients), or the type of chemotherapy used. We also included studies with a paediatric population (younger than 18 years), as long as it was less than 33.3% of the total population of the trial.

We defined fever as a single oral temperature reading above 38.3 °C (101 °F), or a temperature above 38.0 °C (100.4 °F) that was sustained for at least one hour; and neutropenia as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 500 cells/mm³ or less, or an ANC that was expected to decrease to less than 500 cells/mm³ during the next 48 hours (Freifeld 2011). When studies used alternative definitions, we included such studies, provided their definitions meant the same as ours.

Types of interventions

Experimental intervention

Pre‐emptive antifungal therapy referred to treatment that started only when diagnostic tests explicitly suggested the presence of a fungal infection during FN. To investigate the fungal infection, studies were to have used a serological test (e.g. blood β‐D‐glucan, blood galactomannan antigen, serum Candida spp. or Aspergillus spp. detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)), an imaging study (e.g. chest X‐ray or pulmonary or sinus computed tomography (CT)), or both.

Comparison interventions

Empirical antifungal therapy referred to treatment with broad‐spectrum antibacterials that was initiated after several consecutive days of persistent FN.

If studies used alternative definitions, we included such studies, provided their definitions meant the same as ours.

Types of outcome measures

We evaluated one primary outcome and five secondary outcomes.

Primary outcomes

We considered all‐cause mortality as the primary outcome (survival period was defined as the time interval from random treatment assignment to either death from any cause or the last follow‐up).

We did not separate the primary outcome data into short‐ (2 to 6 weeks), medium‐ (7 to 16 weeks), and long‐term (17 to 48 weeks) mortality (Higgins 2022). When possible, we also estimated mortality that occurred during hospitalisation.

Secondary outcomes

-

Treatment failure

Mortality ascribed to fungal infection: defined as death with clinical or autopsy diagnosis of refractory invasive fungal disease (IFD), in the absence of other causes

-

Other outcomes

Proportion of antifungal agent use (other than prophylactic use), defined as the proportion of study participants who received antifungal agents other than prophylactic use during the study period.

Duration of antifungal agent use (days)

Invasive fungal infection detection, defined according to the criteria of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Mycoses Study Group, when available (Ascioglu 2002; Donnelly 2020; De Pauw 2008)

Adverse events (e.g. treatment discontinuation, nephrotoxicity, hepatic dysfunction), according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0 2017, when available (National Cancer Institiute 2017)

We prepared a summary of findings table that reported the following outcomes, listed in order of priority.

All‐cause mortality

Mortality ascribed to fungal infection

Proportion of antifungal agent use (other than prophylactic use)

Duration of antifungal agent use

Invasive fungal infection detection

Adverse events

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2021, Issue 10) in the Cochrane Library (searched 12 October 2021; Appendix 1);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to September week 5 2021; Appendix 2);

Embase Ovid (1980 to 2021 week 40; Appendix 3);

PubMed (1966 to October 2021).

We searched trial databases, specifically current controlled trials in the National Institutes of Health database (clinicaltrials.gov/), for ongoing and unpublished trials.

Searching other resources

We reviewed the references of all included studies for additional trials. We handsearched the following conference proceedings:

European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (2001 to Oct 2021);

Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC) and American Society of Mircrobiology (ASM) Microbe (2001 to Oct 2021);

Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and ID Week (2001 to Oct 2021);

European Society for Medical Oncology Congress (2001 to Oct 2021);

American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting (2001 to Oct 2021); and

American Society of Haematology (ASH) Annual Meeting (2001 to Oct 2021).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We downloaded all titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching into Covidence and removed duplicates. Two review authors (YU and HI) independently screened the titles and abstracts, and excluded those that clearly did not meet the following inclusion criteria:

Is the study described as an RCT?

Does the study compare pre‐emptive therapy with empirical therapy?

Were the participants identified as people with cancer?

We obtained full‐text copies of any potentially relevant references and assessed the eligibility of the retrieved articles. We resolved any disagreement through discussion, or, if required, we consulted a third person (YM). We identified and excluded duplicate reports and collated multiple reports of the same study, so that each study rather than each report was the unit of interest in the review. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram and the characteristics of included and excluded studies tables (Moher 2009).

Data extraction and management

The same review authors (YU and HI) designed a data extraction form (Appendix 4). We extracted the following information and data.

General information (i.e. title, authors, contact information, country, language and year of publication, sponsors and conflict of interests)

Trial characteristics (e.g. study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, publication status, study years, number of centres, randomisation procedure, allocation concealment, blinding procedure, early termination, completeness of data, presence of selective reporting, assessment of compliance, handling of withdrawals, losses to follow‐up, type of analysis, and presence of other sources of bias)

Participant characteristics (i.e. type of population, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and baseline characteristics)

Information regarding the intervention (i.e. what test was used before the antifungal drug administration started)

Information regarding outcomes (e.g. all‐cause mortality, mortality ascribed to fungal infection, IFD detection, proportion of antifungal agent use (other than prophylactic use), adverse events, cost, and other reported outcomes)

All individuals randomised in the outcome assessment, preferably by intention‐to‐treat; when a single study provided data for multiple measures of the same outcome, we chose the measure that best fit our outcome definitions

For dichotomous outcomes, we recorded the number of participants manifesting the outcome in each group, as well as the number of evaluated participants per group

For continuous outcomes, we documented values as well as the measure chosen to report data (e.g. mean with standard deviation (SD) and median with interquartile range)

The two review authors (YU and HI) entered the collected data into the Review Manager 5 file (RevMan 5 (Review Manager 2020)). We double‐checked if the data were entered correctly by comparing the data in RevMan 5 with the study reports. A third review author (YM) independently reviewed the extracted data for accuracy, and resolved any disagreements.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The two authors (YU and HI) independently assessed risk of bias in each study by using the following items:

selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment),

performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel),

detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment),

attrition bias (incomplete outcome data; defined as high risk when the number of randomised participants was not provided, or the outcome reported was less than 80% of the randomised population without justification),

reporting bias (selective reporting), and other biases.

We expressed the classification of the specific risks of bias as low, high, or unclear risk of bias, using the criteria suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017). We resolved any disagreement by discussion. We detailed the risk of bias assessment in the Characteristics of included studies table, and graphically presented the results in risk of bias summary tables.

Measures of treatment effect

For continuous outcomes, we extracted means with SD from the studies. If reported differently in a trial, we contacted the trial authors to request the means and SD. We computed the mean difference (MD) and the 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each study. For all dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the risk ratios (RR) for individual studies, with 95% CI. We did not plan to analyse time‐to‐event data (e.g. hazard ratios).

Unit of analysis issues

We presented the included studies in a parallel‐group design; the unit of analysis was expected to be the individual participant. If we included cluster‐randomised trials, we planned to use the published effect estimates, with clustering taken into account. When the original report correctly analysed the cluster‐randomised study, we planned to enter the effect estimate and standard error, using the generic inverse‐variance method in RevMan 5.

If the original report failed to adjust for cluster effects, we planned to include the studies only when we could extract the following information:

number of clusters randomised to each intervention, or the average size of each cluster,

outcome data, ignoring the cluster design, for the total number of participants, and

estimate of the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC).

We planned to use the ICC from similarly designed studies when such were available. Then, we planned to conduct the approximately correct analysis following the procedures described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2022). If multiple‐arm trials were included, we planned to consider within‐study correlation, by calculating the average of the relevant pairwise comparisons from the study, and calculating a variance for the study, accounting for the correlation between the comparisons. If the control group was a common comparator in a comparison, we planned to divide the participants by the number of relevant intervention groups, to avoid double counting the same data. For trials that had a cross‐over design, we planned to only consider results from the first randomisation period, to avoid period effects.

Dealing with missing data

We requested missing information from the study authors, but were not successful in all cases. The primary analysis was an intention‐to‐treat analysis (ITT), wherein all participants randomised to treatment were included in the denominator. This analysis assumed that all losses to follow‐up had favourable outcomes. To explore the impact of the missing data on the summary effect estimate for death, we planned to conduct a sensitivity analysis.

If the data were not available for an ITT analyses, we analysed the data with a per‐protocol approach. We described and critiqued any methods, such as imputation, reported in the publication to address incomplete data. In the discussion section of the review, we considered the impact of missing data on the review findings. If possible, we planned to impute missing SDs from other reported studies, by using the maximum reported values in those studies. In all cases, we considered the most conservative assumptions.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We tested for statistical heterogeneity between trials by using the Chi² test (P < 0.1 was considered statistically significant), and the I² statistic, along with a visual inspection of the forest plots. We interpreted I² values in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2022). An approximate guide to interpretation was:

0% to 40% might not be important;

30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100% indicates considerable heterogeneity.

We also kept in mind that the importance of the observed value in the I² statistic depends on the magnitude and direction of effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity. We conducted subgroup and sensitivity analyses if the I² was above 50%.

Assessment of reporting biases

Had we pooled more than 10 studies, we planned to proceed with the relevant statistical test for funnel plot asymmetry to explore possible small study biases. Since we pooled fewer than 10 trials, we included a narrative description of the risk of reporting bias.

Data synthesis

We analysed the data using RevMan 5 (Review Manager 2020). We individually combined included studies in a meta‐analysis. Given the nature of the intervention, we used a random‐effects model. When we detected substantial and considerable heterogeneity (I² > 75%), we investigated potential source of the heterogeneity and downgraded the evidence.

For dichotomous data, we pooled RRs by using the Mantel–Haenszel method. For continuous data, we calculated the mean difference (MD) when data were reported using the same scale, or standardised mean difference (SMD) for data reported in different scales. We reported pooled estimates with 95% CI.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We pre‐planned and addressed the following potential effect modifiers of the primary outcome (all‐cause mortality).

documented infection (clinically or microbiologically) versus fever of unknown aetiology

high‐risk participants versus low‐risk participants, preferably defined by a Multinational Association for Supportive Care (MASCC) score, but we accepted and documented the study definitions

people with solid tumour versus people with haematological malignancy

severity of neutropenia (ANC < 100 cells/mm³ versus ANC between 100 cells/mm³ and 500 cells/mm³), referring to the lowest ANC documented (nadir of neutropenia)

anti‐mould prophylaxis versus non‐anti‐mould prophylaxis

selection of antifungal agents

people undergoing stem‐cell transplantation versus people undergoing chemotherapy (we expected stem‐cell transplantation)

Sensitivity analysis

We planned sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome, based on risk bias (only including data from trials at low risk of bias); missing data (only including data from trials without missing data), and the presence of heterogeneity (only including data from trials with homogenous interventions). We added sensitivity analyses for all‐cause mortality reported in the short‐term (2 to 6 weeks), and medium‐term (7 to 16 weeks). Since Hebart 2009 reported all‐cause mortality at both short‐ and medium‐term time points, we added another sensitivity analysis in which we replaced medium‐term data for short‐term data.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We presented the overall certainty of the evidence for each outcome according to the GRADE approach, which took into account issues related to internal validity (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias), and external validity, such as directness of results (Langendam 2013; Schünemann 2011). We created a summary of findings table, following the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2022), using GRADEPro GDT software. We downgraded the evidence from high certainty by one level for serious (or by two for very serious) concerns for each limitation. We used the GRADE approach and GRADE Working Group certainty of evidence definitions, listed below (Meader 2014).

High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

We evaluated the evidence for all‐cause mortality, mortality ascribed to fungal infection, proportion of antifungal agent use (other than prophylactic use), duration of antifungal use (days), invasive fungal infection detection, and adverse effects, for the comparison between empirical antifungal therapy and pre‐emptive antifungal therapy.

Since we were unable to undertake meta‐analysis for all outcomes, we presented our results in a hybrid summary of findings table format (both quantitative and narrative), such as that used by Chan 2011.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

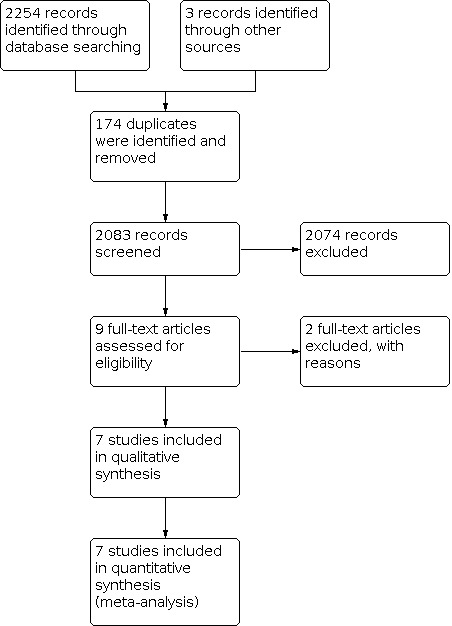

We retrieved 2254 reports from the systematic literature search, one abstract from an academic conference, and two studies by handsearching. After Covidence removed 174 duplicate records, we screened 2083 records. We unanimously included seven records after title and abstract screening, and two after discussing 19 conflict points. We assessed the full text of nine reports for eligibility (Figure 1).

1.

PRISMA flow diagram, illustrating study selection

Included studies

We included seven trials included in the review. See Characteristics of included studies for details.

The included studies only enroled 1480 people with high‐risk febrile neutropenia (FN; e.g. people with haematological malignancy); none with low‐risk FN (e.g. people with solid tumour). We found variability in the definition of pre‐emptive treatment (e.g. laboratory tests with or without quantitative real‐time PCR assays, ELISA, galactomannan test; imaging with or without high‐resolution computed tomography; prophylaxis; antifungal agents). Three were single‐centred, and four were multicentre trials.

Excluded studies

We excluded two reports after full‐text review, and described the reasons in the Characteristics of excluded studies; one had the wrong intervention, and one was not a randomised trial.

Risk of bias in included studies

For details of the risk of bias judgements for each study, see Characteristics of included studies. See Figure 2 for the graphical representation of the overall risk of bias across included studies.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

Allocation

Sequence generation Four studies described the method of randomisation in detail (low risk of bias); three did not, and the process was unclear (unclear risk of bias).

Allocation concealment Appropriate allocation concealment was performed in five studies (low risk of bias), and the process was unclear in two studies that did not provide a detailed description (unclear risk of bias).

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel

Blinding of participants, healthcare professionals, and investigators was not feasible due to the nature of the intervention. Non‐blinded or open label was clearly stated in four studies, and not in three studies (high risk of bias).

Blinding of outcome assessment

Five of the seven studies reported a blinded outcome assessor, so we assessed them at low risk of bias; we assessed the other two as unclear risk of bias, because of lack of information.

Incomplete outcome data

All studies clearly stated the process from participant enrolment to allocation and outcome assessment (low risk of bias), but there was a serious risk of bias in Blennow 2010; only 21 out of 41 enroled people were randomised (high risk of bias).

Selective reporting

Four studies had clinical trial registration. We did not identify any apparent selective reporting, and judged them at low risk of bias. Since there were no protocols or clinical trial registrations for the other three studies, we rated them at unclear risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Five studies transparently described the study process, and we did not identify other potential biases (low risk of bias). The other two studies lacked sufficient information to assess other biases (unclear risk of bias).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See: Table 1

Six included studies reported the effect on all‐cause mortality; five reported on mortality ascribed to fungal infection; seven reported on the proportion of antifungal agent use (other than prophylactic use); three reported on the duration of antifungal use in days; seven reported on invasive fungal infection detection; and four reported adverse events.

Primary outcome

All‐cause mortality

There may be little to no difference between groups for all‐cause mortality (risk ratio (RR) 0.97, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.72 to 1.30; absolute effect – reduction of 3 out of 1000; 6 studies, 1459 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1). No evidence of heterogeneity was identified for this outcome (Chi² = 3.31, I² = 0%).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Pre‐emptive versus empirical antifungal therapy, Outcome 1: All‐cause mortality

Secondary outcomes

Mortality ascribed to fungal infection

There may be little to no difference between groups for mortality ascribed to fungal infection (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.89; absolute effect – reduction of 2 out of 1000; 5 studies, 1407 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.2). No evidence of heterogeneity was identified for this outcome (Chi² = 4.48, I² = 11%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Pre‐emptive versus empirical antifungal therapy, Outcome 2: Mortality ascribed to fungal infection

Proportion of antifungal agent use (other than prophylactic use)

Pre‐emptive therapy may reduce the proportion of antifungal agent used (other than prophylactic use; RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.05; absolute effect – reduction of 125 out of 1000; 7 studies, 1480 participants; very low‐certainty evidence: Analysis 1.3). There was considerable heterogeneity for this outcome (Chi² = 49.0, I² = 88%); intervention protocols for antifungal agents used were heterogeneous across included studies.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Pre‐emptive versus empirical antifungal therapy, Outcome 3: Proportion of antifungal agent use (other than prophylactic use)

Duration of antifungal use (days)

Pre‐emptive therapy may reduce the duration of antifungal use more than empirical therapy (mean difference (MD) ‐3.52 days, 95% CI ‐6.99 to ‐0.66; 3 studies, 764 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.4). There was considerable heterogeneity for this outcome (Chi² = 14.64, I² = 86%).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Pre‐emptive versus empirical antifungal therapy, Outcome 4: Duration of antifungal use (days)

Invasive fungal infection detection

Pre‐emptive therapy may increase invasive fungal infection detection more than empirical treatment (RR 1.70, 95% CI 0.71 to 4.05; absolute effect – increased by 43 out of 1000; 7 studies, 1480 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.5). There was considerable heterogeneity for this outcome (Chi² = 23.54, I² = 75%).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Pre‐emptive versus empirical antifungal therapy, Outcome 5: Invasive fungal infection detection

Adverse events

Four of the seven trials reported adverse events. Since the adverse events and evaluating methods were different among the trials, we did not undertake a meta‐analysis. Narrative summary of the adverse events follows.

Hebart 2009 reported 39/152 (25.7%) cases of nephrotoxicity in the pre‐emptive therapy group, and 28/92 (30.4%) cases in the empirical therapy group.

Morrissey 2013 reported 12/118 (10%) cases of hepatotoxicity in the pre‐emptive therapy group, and 21/122 (17%; P = 0.11) in the empirical therapy group. They also reported 60/118 (51%) cases of nephrotoxicity in the pre‐emptive therapy group, and 52/122 (43%; P = 0.21) in the empirical therapy group.

In Cordonnier 2009, the mean decrease of creatinine clearance ± standard deviation (SD) was larger in the empirical therapy group (‐8.7 ± 20.8) than in the pre‐emptive therapy group (‐5.8 ± 27.2). Severe adverse events occurred in similar proportions among the two groups.

In Yuan 2016, 1/26 courses (3.8%) of antifungal treatment administered during pre‐emptive therapy, and 2/43 courses (4.7%) of empirical therapy led to adverse events, for which antifungal treatment was discontinued (P = 0.874).

Subgroup analysis

We had planned a number of subgroup analyses for the primary outcome (prophylaxis, cancer type, risk of FN, selection of antifungal agents, severity of neutropenia, type of chemotherapy), but the reports all lacked sufficient information to enable us to do so. Our enquiries to corresponding authors of each of the studies did not garner enough data. Therefore, we did not perform any subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity Analysis

Results were consistent for all‐cause mortality when we excluded data from trials with higher risk of bias (Analysis 2.1); replaced medium‐term with short‐term outcome data for Hebart 2009 (Analysis 2.2), or separately analysed short‐term (2 to 6 weeks; Analysis 2.3), and medium‐term (7 to 16 weeks) outcome data (Analysis 2.4).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Sensitivity analyses for all‐cause mortality, Outcome 1: RCTs at lower risk of bias

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Sensitivity analyses for all‐cause mortality, Outcome 2: Replacing outcomes for Hebart 2009

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Sensitivity analyses for all‐cause mortality, Outcome 3: Short‐term time point

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Sensitivity analyses for all‐cause mortality, Outcome 4: Medium‐term time point

We were unable to undertake sensitivity analyses for trials with no missing data, or those with homogenous interventions, as planned, due to lack of data.

Reporting bias

We did use a funnel plot to assess reporting bias because we only included seven trials. It was difficult to fully evaluate reporting bias, because not all trials had clinical trial registrations, and published protocols.

Discussion

Summary of main results

See Table 1 for the comparison, pre‐emptive versus empirical antifungal therapy for febrile neutropenia in people with cancer.

We included seven randomised controlled trials, with 1480 participants in this review.

There may be little to no difference between groups for all‐cause mortality (risk ratio (RR) 0.97, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.72 to 1.30); and mortality ascribed to fungal infection (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.89).

Pre‐emptive therapy may decrease antifungal agent use (other than prophylactic use; RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.05); and the duration of antifungal use (mean difference (MD) ‐3.52, 95% CI ‐6.99 to ‐0.06) over pre‐emptive therapy.

Although we could not undertake a meta‐analysis of adverse events, narratively, there seemed to be no apparent difference in the frequency or severity of adverse events between groups.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Our conclusions were based on data from seven studies that met our inclusion criteria. We completed sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome, all‐cause mortality, for risk of bias and measurement time point. We found that these results were consistent with the primary analysis, which supported the robustness of the effect. We were unable to complete our pre‐planned subgroup analysis, due to lack of data.

Each study used their own specific antifungal protocols for both pre‐emptive and empirical antifungal therapies. The results from this review were based on clinically heterogeneous evidence, and did not provide a clear answer as to which protocol should be implemented in clinical practice.

The two outcomes associated with mortality exhibited less statistically heterogeneity, suggesting that whatever protocol chosen may have little impact on mortality. The two outcomes of clinical resource utilisation, and the identification rate of invasive fungal disease (IFD) showed considerable statistical heterogeneity (I2 > 75%), which might reflect the effects of different intervention and outcome evaluation protocols.

Quality of the evidence

We judged all seven of the included studies to have some risk of bias, in particular, none of the participants or personnel were blinded. We downgraded the certainty of the evidence for all outcomes by one level due to lack of blinding. We identified non‐negligible clinical and statistical heterogeneity for each outcome, which was a critical factor of indirectness, for which we downgraded the certainty by another level, or two (for serious indirectness). Since we were unable to pool the data for adverse events, we downgraded by another level for sparse data.

Potential biases in the review process

First, our literature search strategy seemed have limited sensitivity. Although it was not specified in the title and abstract as pre‐emptive treatment, there were studies that conceptually, could be regarded as pre‐emptive treatment (Blennow 2010; Morrissey 2013). These studies were included in a previous review by Fung 2015; we identified them by handsearching.

Second, we were unable to conduct subgroup analyses. Efficacy of pre‐emptive treatment can be modified by various factors, including our pre‐planned factors. Since subgroup analysis contributes to the identification of suitable treatment populations, future studies would be encouraged to report the results of various subgroup analysis in detail.

Third, we meta‐analysed various evaluation periods for the primary endpoints. Initially, we planned analyses for short‐term, medium‐, and long‐term outcomes, but we only had seven trials. The main analysis had low statistical heterogeneity, but the short‐term and medium‐term evaluations, as sensitivity analysis, had higher statistical heterogeneity. It would be reasonable to develop a consensus on the clinically optimal evaluation period.

Finally, the novel concept of antifungal treatment strategy for FN has been developed in recent years. Kanda 2020 developed D‐Index‐Guided Early Antifungal Therapy and demonstrated promising efficacy. When we update the current review, it will be necessary to update the review questions, including not only a comparison between pre‐emptive and experiential therapy, but also the novel treatment strategies.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Fung 2015 conducted a systematic review and meta‐analysis of the same research question as this review in 2015, which included nine studies: five RCTs, and four non‐RCT study designs. We included these five RCTs, and we also added two further studies.

They concluded that "Compared to empirical antifungal therapy, pre‐emptive strategies were associated with significantly lower antifungal exposure (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.85) and duration, without an increase in IFD‐related mortality (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.87) or overall mortality (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.99)". Our results were similar. The statistical heterogeneity associated with mortality improved in our review, which may be due to the focus on randomised controlled trials and the addition of new studies. Both reviews showed considerable statistical heterogeneity in IFD identification and antifungal agent use. The duration of antifungal use was only meta‐analysed in our review.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

For people with cancer and high‐risk febrile neutropenia, pre‐emptive antifungal therapy may reduce the duration and rate of use of antifungal agents without deteriorating all‐cause and invasive fungal disease‐related mortality, compared to empirical therapy. But the evidence regarding invasive fungal infection detection and adverse events was inconsistent and uncertain.

Implications for research.

Future research should focus on:

Developing a standardised protocol for pre‐emptive antifungal therapy;

Defining the target population for pre‐emptive antifungal therapy, reporting the detailed and various subgroup analysis;

Developing a consensus on the clinically optimal evaluation period for mortality and other relevant outcomes.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 5, 2020

Acknowledgements

We thank the Cochrane Gynaecological, Neuro‐oncology and Orphan Cancers (GNOC), in particular, Jo Morrison, Co‐ordinating Editor; Jo Platt for designing the search strategy; Gail Quinn, Clare Jess, and Tracey Harrison for their contribution to the editorial process; and Anat Gafter‐Gvili for her clinical advice as Contact Editor.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), via Cochrane infrastructure funding to the Cochrane Gynaecological, Neuro‐oncology and Orphan Cancers Group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the review authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS, or the Department of Health.

The authors and the GNOC Team are grateful to the following peer reviewers for their time and comments: Andrew Byrant and Anat Stern; and Victoria Pennick for copy editing the review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Neoplasms] explode all trees #2 cancer* or tumor* or tumour* or neoplas* or malignan* or carcinoma* or adenocarcinoma* or choriocarcinoma* or leukemia* or leukaemia* or metastat* or sarcoma* or teratoma* #3 #1 or #2 #4 MeSH descriptor: [Invasive Fungal Infections] explode all trees #5 MeSH descriptor: [Antifungal Agents] explode all trees #6 (antifung* or anti fung* or anti‐fung*) near/5 (therap* or treat* or agent* or manag* or method* or car* or service* or plan* or intervention*) #7 fung* near/5 infect* #8 (pre‐emptive* or pre emptive* or preemptive* or presumptive*) near/5 therap* #9 (empirical or empiric) near/5 therap* #10 #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 #11 MeSH descriptor: [Febrile Neutropenia] explode all trees #12 febrile neutrop* or febrile‐neutrop* or FN* or neutropenia* #13 (fever* or pyrexia* or temperature* or hyperthermia) near/8 neutrop* #14 #11 or #12 or #13 #15 #3 and #10 and #14

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search strategy

1. exp Neoplasms/ 2. (cancer* or tumor* or tumour* or neoplas* or malignan* or carcinoma* or adenocarcinoma* or choriocarcinoma* or leukemia* or leukaemia* or metastat* or sarcoma* or teratoma*).mp. 3. 1 or 2 4. exp Invasive Fungal Infections/ 5. exp Antifungal Agents/ 6. ((antifung* or anti fung* or anti‐fung*) adj5 (therap* or treat* or agent* or manag* or method* or car* or service* or plan* or intervention*)).mp. 7. (fung* adj5 infect*).mp. 8. ((pre‐emptive* or pre emptive* or preemptive* or presumptive*) adj5 therap*).mp. 9. ((empirical or empiric) adj5 therap*).mp. 10. 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 11. exp Febrile Neutropenia/ 12. (febrile neutrop* or febrile‐neutrop* or FN* or neutropenia*).mp. 13. ((fever* or pyrexia* or temperature* or hyperthermia) adj8 neutrop*).mp. 14. 11 or 12 or 13 15. 3 and 10 and 14 16. randomized controlled trial.pt. 17. controlled clinical trial.pt. 18. randomized.ab. 19. placebo.ab. 20. drug therapy.fs. 21. randomly.ab. 22. trial.ti. 23. groups.ab. 24. 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 25. (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. 26. 24 not 25 27. 15 and 26

Appendix 3. Embase search strategy

1. exp neoplasm/ 2. (cancer* or tumor* or tumour* or neoplas* or malignan* or carcinoma* or adenocarcinoma* or choriocarcinoma* or leukemia* or leukaemia* or metastat* or sarcoma* or teratoma*).mp. 3. 1 or 2 4. exp systemic mycosis/ 5. exp antifungal agent/ 6. ((antifung* or anti fung* or anti‐fung*) adj5 (therap* or treat* or agent* or manag* or method* or car* or service* or plan* or intervention*)).mp. 7. (fung* adj5 infect*).mp. 8. ((pre‐emptive* or pre emptive* or preemptive* or presumptive*) adj5 therap*).mp. 9. ((empirical or empiric) adj5 therap*).mp. 10. 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 11. exp febrile neutropenia/ 12. (febrile neutrop* or febrile‐neutrop* or FN* or neutropenia*).mp. 13. ((fever* or pyrexia* or temperature* or hyperthermia) adj8 neutrop*).mp. 14. 11 or 12 or 13 15. 3 and 10 and 14 16. crossover procedure/ 17. double‐blind procedure/ 18. randomized controlled trial/ 19. single‐blind procedure/ 20. random*.mp. 21. factorial*.mp. 22. (crossover* or cross over* or cross‐over*).mp. 23. placebo*.mp. 24. (double* adj blind*).mp. 25. (singl* adj blind*).mp. 26. assign*.mp. 27. allocat*.mp. 28. volunteer*.mp. 29. 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 30. 15 and 29

Appendix 4. Data extraction form

| Assessor | YU | YU | ||

| Date of Assessment | 29/08/2019 | 29/08/2019 | ||

| Study ID | ABC 2019 | ABC 2019 | ||

| Intervention or control | Intervention | Control | ||

| Labels for intervention and control groups | Pre‐emptive | Empirical | ||

| General Information | Title | |||

| Authors | ||||

| Contact person/affiliation | ||||

| Contact address | ||||

| Country | ||||

| Language | ||||

| Year of publication | ||||

| Sponsors | ||||

| Conflict of interests | ||||

| Trial Characteristics | RCT type | |||

| inclusion criteria | ||||

| exclusion criteria | ||||

| Publication status | ||||

| Study years | ||||

| Number of centres | ||||

| Participants' characteristics | Population | |||

| No. randomised | ||||

| Age: mean (SD) | ||||

| female (%) | ||||

| Haematological malignancy (%) | ||||

| Patients undergoing stem‐cell transplantation (%) | ||||

| High‐risk participants defined by MASCC score (%) | ||||

| Severe neutropenia (ANC < 100; %) | ||||

| Antifungal prophylaxis (%) | ||||

| Anti‐mould prophylaxis (%) | ||||

| Information regarding the intervention | Pre‐emptive protocol | |||

| Empirical protocol | ||||

| Diagnostic testing | ||||

| Escalation antifungal drug | ||||

| Outcomes 1: All‐cause mortality | post‐intervention | timing | ||

| definition of events | ||||

| number of events (if only continuous data were provided, write down mean (SD) | ||||

| number in denominator | ||||

| indirectness of the outcome | ||||

| Outcome 2: Mortality ascribed to fungal infection | post‐intervention | timing | ||

| definition of events | ||||

| number of events (if only continuous data were provided, write down mean (SD) | ||||

| number in denominator | ||||

| indirectness of the outcome | ||||

| Outcome 3: Proportion of antifungal agent use | post‐intervention | timing | ||

| definition of events | ||||

| number of events (if only continuous data were provided, write down mean (SD) | ||||

| number in denominator | ||||

| indirectness of the outcome | ||||

| Outcome 4: Duration of antifungal agent use | post‐intervention | timing | ||

| definition of events | ||||

| number of events (if only continuous data were provided, write down mean (SD) | ||||

| number in denominator | ||||

| indirectness of the outcome | ||||

| Outcome 5: Invasive fungal infection detection | post‐intervention | timing | ||

| definition of events | ||||

| number of events (if only continuous data were provided, write down mean (SD) | ||||

| number in denominator | ||||

| indirectness of the outcome | ||||

| Outcome 6: Adverse events | post‐intervention | timing | ||

| definition of events | ||||

| number of events (if only continuous data were provided, write down mean (SD) | ||||

| number in denominator | ||||

| indirectness of the outcome | ||||

| Outcome X: additional probably important outcome 1 | post‐intervention | timing | ||

| definition of events | ||||

| number of events (if only continuous data were provided, write down mean (SD) | ||||

| number in denominator | ||||

| indirectness of the outcome | ||||

| Outcome Y: additional probably important outcome 2 | post‐intervention | timing | ||

| definition of events | ||||

| number of events (if only continuous data were provided, write down mean (SD) | ||||

| number in denominator | ||||

| indirectness of the outcome | ||||

| Risk of bias | Random sequence generation | |||

| Allocation concealment | ||||

| Blinding | ||||

| Incomplete outcome data | ||||

| Selective reporting | ||||

| Other bias | ||||

| Overall RoB | ||||

| Indirectness | participants | |||

| intervention | ||||

| control condition | ||||

| overall indirectness |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Pre‐emptive versus empirical antifungal therapy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 All‐cause mortality | 6 | 1459 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.72, 1.30] |

| 1.2 Mortality ascribed to fungal infection | 5 | 1407 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.45, 1.89] |

| 1.3 Proportion of antifungal agent use (other than prophylactic use) | 7 | 1480 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.47, 1.05] |

| 1.4 Duration of antifungal use (days) | 3 | 764 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.52 [‐6.99, ‐0.06] |

| 1.5 Invasive fungal infection detection | 7 | 1480 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.70 [0.71, 4.05] |

Comparison 2. Sensitivity analyses for all‐cause mortality.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 RCTs at lower risk of bias | 5 | 1191 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.68, 1.26] |

| 2.2 Replacing outcomes for Hebart 2009 | 6 | 1459 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.52, 1.38] |

| 2.3 Short‐term time point | 3 | 964 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.25, 3.55] |

| 2.4 Medium‐term time point | 2 | 455 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.65, 1.50] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Aguado 2015.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Study design: open‐label, parallel‐group, randomised trial Country: Spain Number of centres: 13 |

|

| Participants | Adults (≥ 18 years) with AML or high‐risk MDS undergoing remission induction therapy for newly diagnosed or relapsed or refractory disease and people undergoing allo‐HSCT. People with the diagnosis of IA within 6 months prior to or at enrolment, the receipt of antifungal therapy with anti‐Aspergillus activity within 30 days prior to or at enrolment, and a history of hypersensitivity to azoles, were excluded. | |

| Interventions |

Pre‐emptive therapeutic protocol: Serum GM and Aspergillus species quantitative rtPCR assays were performed twice a week until neutrophil recovery reached ≥ 0.5 × 10^3 cells/mm^3 for people with AML/MDS, or until days 180 or 100 for allo‐HSCT recipients with or without GVHD, respectively. The results of both GM and rtPCR assays were provided to the attending physicians of participants allocated into the GM‐PCR group; in the GM group, only the results of the GM assay were provided. In both groups, these results were available within 24 to 48 hours from sampling. When the result of at least 1 of the tests were positive, ordering a thoracic HRCT scan was mandatory and an antifungal agent with activity against Aspergillus species had to be initiated, even if the HRCT scan revealed no radiological signs suggestive of IA, according to the EORTC/MSG criteria. Of note, the rtPCR results generated from the GM group had no influence on the clinical management of these participants, or on the decision of whether to order an imaging study. Febrile neutropenia episodes were managed with broad‐spectrum antibiotics according to the local practice at each centre. Attending physicians were allowed to order additional HRCT scan examinations whenever they deemed them clinically necessary. Empirical therapeutic protocol: Empirical antifungal therapy had to be prescribed after 72 hours of the onset of refractory febrile neutropenia, even if no evidence of IA was present, and subsequently, the participant's withdrawal from the study was mandatory. |

|

| Outcomes |

Time points for assessment: the follow‐up period extended from the date of first monitoring until 30 days after the resolution of neutropenia for participants with AML/MDS, or until days 210 or 130 days for allo‐HSCT recipients with or without GVHD, respectively. Primary outcome: 1. Cumulative incidence of proven or probable IA according to the EORTC/MSG criteria. Secondary outcome: 1. All‐cause and proven or probable IA‐attributable mortality 2 Proven or probable IA‐free survival 3. Cumulative incidence of any EORTC/MSG category of IA (possible, probable, or proven) 4. Antifungal consumption |

|

| Notes | Study period: February 2011 to September 2012 Funding source: this study was supported by an unrestricted grant from Pfizer. Declarations of interest among the researchers: J. M. A. received grant support from Astellas Pharma, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), Pfizer, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness), and the Mutua Madrileña Foundation; was an advisor/consultant to Astellas Pharma, Gilead Sciences, MSD, and Pfizer; and received honoraria for talks on behalf of Gilead Sciences, MSD, Pfizer, and Astellas Pharma. L. V. received grant support from Astellas Pharma, Gilead Sciences, MSD, Pfizer, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness), and the Mutua Madrileña Foundation; was an advisor/consultant to Astellas Pharma, Gilead Sciences, MSD, and Pfizer; and received honoraria for talks on behalf of Gilead Sciences, MSD, Pfizer, and Astellas Pharma. M. F.‐R. received honoraria for talks on behalf of Pfizer. I. R.‐C. received honoraria for talks on behalf of Pfizer, MSD, Gilead, Astellas, and Novartis. P. B. received honoraria for talks on behalf of Gilead Sciences, Pfizer, and Astellas Pharma. M. B. received grant support from Pfizer. C. S. received grant support from Astellas Pharma, Gilead Sciences, Pfizer, and Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness); was an advisor/consultant to Astellas Pharma, Gilead Sciences, MSD, and Pfizer; and received honoraria for talks on behalf of Gilead Sciences, MSD, Pfizer, and Astellas Pharma. D. G. received grant support from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness) and the Mutua Madrileña Foundation. R. V. was an advisor/consultant to Gilead Sciences. C. V. received grant support from Pfizer; was an advisor/consultant to Astellas Pharma, Gilead Sciences, MSD, and Pfizer; and received honoraria for talks on behalf of Gilead Sciences, MSD, and Pfizer. M. C.‐E. received grant support from Astellas Pharma, bioMérieux, Gilead Sciences, MSD, Pfizer, Schering‐Plough, Soria Melguizo SA, Ferrer International, the European Union, the ALBAN program, the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation, the Spanish Ministry of Culture and Education, the Spanish Health Research Fund, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness), the Ramon Areces Foundation, and the Mutua Madrileña Foundation; was an advisor/consultant to the Pan American Health Organization, Astellas Pharma, Gilead Sciences, MSD, Pfizer, and Schering‐Plough; and was paid for talks on behalf of Gilead Sciences, MSD, Pfizer, Astellas Pharma, and Schering‐Plough. All other authors reported no potential conflicts. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | An independent statistician performed the procedure by using a computer‐generated schedule of randomly permuted blocks. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Phone confirmation of the allocated group was provided by independent statistician. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open‐label, controlled, parallel‐group randomised trial |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Laboratory technicians who performed the monitoring assays were blinded to the intervention, and all the study outcomes were reviewed by an independent adjudication committee. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | This study clearly stated the process from participant enrolment to allocation and outcome assessment; attrition rate was 7.3% (16/219). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | There was a clinical trial registration and no apparent selective reporting was identified. |

| Other bias | Low risk | This study transparently described the study process, and other apparent biases were not identified. |

Blennow 2010.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Study design: prospective, randomised, non‐blinded study Country: Sweden Number of centres: 1 |

|

| Participants | People undergoing HSCT after RIC at the Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge, were included. People with hypersensitivity to liposomal amphotericin B were excluded. | |

| Interventions | Participants were followed once a week with fungal PCR for the first 100 days after transplantation. Pre‐emptive therapeutic protocol: Participants with a positive PCR result were treated with liposomal amphotericin. Liposomal amphotericin B was given at a dose of 3 mg/kg/day for participants with positive PCR for Aspergillus. After 3 days, the dose was reduced to 1 mg/kg/day if the participant was in a stable clinical condition. For Candida, the treatment dose was 1 mg/kg/day. The treatment was continued until one PCR test was found to be negative in participants without fever and neutropenia, or until two consecutive PCRs were negative in participants with fever and/or neutropenia. Depending on the participant’s clinical status, the treatment could be prolonged according to the judgement of the treating physician. Empirical therapeutic protocol: Participants with fever above 38.5 °C for 3 days despite treatment with antibiotics, and with unknown aetiology, were considered eligible for antifungal treatment regardless of the PCR results. |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome: 1. Success of PCR‐guided antifungal treatment defined as a reduction of proven and probable IFIs in participants allocated to liposomal amphotericin B treatment within 100 days of HSCT Secondary outcome: 1. Survival at 100 days 2. Survival at 1 year 3. 1‐year incidence of IFI 4. Risk factors for IFI |

|

| Notes | Study period: April 2002 and November 2006 Funding source: Sweden Orphan Declarations of interest among the researchers: none |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No clear statement of the blinding; but due to the nature of the intervention, it would be difficult to blind participants, healthcare professionals and investigators. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Laboratory test seemed to be performed at an independent department, however, outcome assessment was unclear. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Only 21.2% (21/99) of participants was randomised. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | There was no protocol or clinical trial registration for this study. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | This study lacked sufficient information to assess the other biases. |

Cordonnier 2009.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Study design: a prospective, randomised, open‐label, non‐inferiority trial Country: France Number of centres: 13 |

|

| Participants | People aged ⩾18 years, with haematological malignancies, and were scheduled for chemotherapy or autologous stem cell transplantation that was expected to cause neutropenia (neutrophil count, < 500 cells/mm3) for at least 10 days. Exclusion criteria: a planned allogeneic transplantation, a history of, or symptoms consistent with IFI, previous severe toxicity from intravenous polyenes, a Karnofsky score < 30%, and HIV seropositivity. |

|

| Interventions |

Pre‐emptive therapeutic protocol: Antifungal treatment was guided by any of the following occurrences, at any time after 4 days of fever and antibacterial treatment: clinically and imaging‐documented pneumonia or acute sinusitis, mucositis of grade 3, septic shock, skin lesion suggesting IFI, unexplained CNS symptoms, periorbital inflammation, splenic or hepatic abscess, severe diarrhoea, Aspergillus colonisation, or ELISA results positive for galactomannan antigenemia. Empirical therapeutic protocol: Persistent or recurrent fever led to initiation of antifungal therapy. |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome: 1. Proportion of participants alive at 14 days after recovery from neutropenia, or for participants with persistent neutropenia at 60 days after inclusion in the study, or an SAE, at the time that these participants were censored Secondary outcome: 1. Fever duration and the proportion of participants with proven or probable IFI 2. Survival at 4 months after inclusion |

|

| Notes | Study period: April 2003 to February 2006 Funding source: French Ministry of Health Declarations of interest among the researchers: C.C. received travel grant and research support from Pfizer Gilead, Merck Sharp & Dohme‐Chibret; and was a consultant for Pfizer Schering‐Ploug, Gilead, Merck Sharp & Dohme‐Chibret, and Zeneuu Pharma |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Participants were assigned in a 1:1 ratio to the empirical or pre‐emptive treatment arms with use of a computer‐generated randomisation scheme with blocks of 4. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Participants were assigned in a 1:1 ratio to the empirical or pre‐emptive treatment arms with use of a computer‐generated randomisation scheme with blocks of 4. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open‐label study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | An independent, blinded adjudication committee reviewed the reasons for starting antifungal therapy, diagnoses of IFI, and causes of death. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | This study clearly stated the process from participant enrolment to allocation and outcome assessment. Protocol violation occurred in 4.1% (12/293) of the participants; no neutropenia occurred in 4.8% (14/293) of the participants. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | There was a clinical trial registration and no apparent selective reporting was identified. |

| Other bias | Low risk | This study transparently described the study process, and other apparent biases were not identified. |

Hebart 2009.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Study design: prospective randomised controlled multicenter trial Country: Germany Number of centres: 5 |

|

| Participants | People who were required to receive Allo‐SCT (BMT or peripheral blood progenitor cell transplantation from related and unrelated donors). People with documented allergy against liposomal amphotericin B, history of IFI at the time of randomisation or before the study entry were excluded. | |

| Interventions |

Pre‐emptive therapeutic protocol: Participants were treated with liposomal amphotericin B after one positive PCR result. If Participants had febrile neutropenia for more than 120 h that was not responding to broad‐spectrum antibacterial therapy, they also received liposomal amphotericin B, even if PCR remained negative. Antifungal treatment lasted for a minimum of 7 days. PCR‐based liposomal amphotericin B therapy was stopped as soon as the granulocyte count had recovered (4500/mL for 3 consecutive days), or if the participant had been afebrile for a minimum of 3 days, presented no signs and symptoms of IFI, and two consecutive PCR results were negative. Empirical therapeutic protocol: Participants received empirical antifungal therapy after 120 h of febrile neutropenia not responding to broad‐spectrum antibacterial therapy. Antifungal treatment lasted for a minimum of 7 days. Empirical liposomal amphotericin B was stopped if the granulocytes had recovered (4500/mL for 3 consecutive days), or if the participant had been afebrile for a minimum of 3 days and presented no radiological signs of invasive aspergillosis. |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome: 1. Incidence of IFIs during the observation period of 100 days after transplantation. Secondary outcome: 1. Survival at day 100 (overall mortality) 2. Survival at day 30 (overall mortality) 3. IFI‐related mortality, 4. Incidence and spectrum of adverse drug reactions |

|

| Notes | Study Period: 1998 to 2001 Funding source: Gilead Declarations of interest among the researchers: none |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Centrally randomised, but detailed randomisation process was unclear |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Central allocation seemed to be performed |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not described, but it seemed to be an open‐label study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All radiological examinations were reviewed by radiologists blinded to the treatment group of the participant |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | This study clearly stated the process from participant enrolment to allocation and outcome assessment; low attrition rate |