Abstract

Introduction

‘Stealth vaping’ is the practice of vaping discreetly in places where electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use is prohibited. While anecdotal evidence suggests that stealth vaping is common, there have been no formal studies of the behaviour. The purpose of this study is to examine stealth vaping behaviour among experienced e-cigarette users.

Methods

Data were collected from the follow-up survey of a large longitudinal cohort study of adult experienced e-cigarette users conducted in January 2017. To measure stealth vaping behaviour, participants were asked ‘Have you ever ‘stealth vaped’, that is to say, used an e-cig in a public place where it was not approved and attempted to conceal your e-cig use? (yes/no)’. Participants indicating yes completed additional questions about the frequency of stealth vaping and were asked to select all the locations where they commonly stealth vape. Frequencies were used to examine the overall prevalence, frequency and common locations for stealth vaping. A logistic regression model was run to predict stealth vaping.

Results

Approximately two-thirds (64.3%, n=297/462) of the sample reported ever stealth vaping, of which 52.5% (n=156/297) reported stealth vaping in the past week. Among stealth vapers (n=297), 31% reported owning a smaller device solely for stealth vaping. The most common places to stealth vape included at work (46.8%), followed by bars/nightclubs (42.1%), restaurants (37.7%), at the movies (35.4%) and in airports/on airplanes (11.7%). Predictors of stealth vaping were greater dependence and owning a smaller device solely for stealth vaping.

Conclusions

Stealth vaping is a common behaviour for many experienced e-cigarette users. More research is needed to understand the reasons for stealth vaping and its potential health and safety implications. This information could help researchers and regulators to design interventions to minimise the public health impact of stealth vaping.

INTRODUCTION

Smoke-free air policies protect non-smokers from hazardous secondhand tobacco smoke, promote quitting and smoking reduction among current smokers, and discourage initiation among youth.1 As of 2011, 28 countries, such as Australia, the UK and Canada, have implemented 100% comprehensive smoke-free policies banning tobacco smoke in non-hospitality workplaces, bars and restaurants.2 While smoke-free air policies are not federal law in the USA, 42 states have implemented restrictions on cigarette smoking in public places.3 Since these smoke-free air laws were enacted, a new tobacco product called an electronic cigarette (e-cigarette, e-cig) has become increasingly popular,4 5 causing countries, states and local governments to extend their current smoke-free laws or develop new laws to include e-cigarette use.6–8 In the USA, as of 23 October 2017, nine states plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico have implemented laws addressing e-cigarette use in indoor places.6 9 In addition to state laws, many local governments are also implementing laws to prohibit indoor e-cigarette use.6

As laws are implemented to prohibit e-cigarette use in public places, it is important to understand the implications of smoke-free air laws for e-cigarette users, including implications for use and dependence. We previously reported that a small proportion of e-cigarette users (12%) find it difficult to refrain from e-cigarette use in places where it is prohibited.10 These users were more dependent and more likely to experience strong cravings compared with those who did not find it difficult to refrain from use. Although it is known that more dependent e-cigarette users find it difficult to refrain from using their e-cigarette when they are not supposed to, it is not known how these users cope with their cravings to use. One potential behaviour to cope with restricted e-cigarette use is to ‘stealth vape’, the practice of vaping discreetly in places where use is known to be banned, including holding the vapour in their mouth long enough to allow it to dissipate before exhaling.11–13

While stealth vaping is commonly discussed online among users,11 12 14 few research studies have examined stealth vaping behaviour. One small qualitative study of current adult e-cigarette users reported that some users stealth vaped and claimed it to be easier than stealth cigarette smoking due to the lack of smell.15 In addition, stealth vaping appears popular among youth who have reported that e-cigarettes are easier to ‘hit’ quickly and then conceal anywhere including at school.16–18

Understanding stealth vaping behaviour is important for several reasons. First, stealth vaping allows nicotine-dependent users to use their e-cigarette more frequently, which could cause greater dependence. In addition, stealth vaping may impact bystanders who could potentially be exposed to harmful chemicals in secondhand vapour.19 Finally, stealth vaping may have the potential to change social norms and promote e-cigarette use among non-users and youth.10 20 21

Despite the potentially detrimental implications associated with stealth vaping and the preliminary evidence that stealth vaping is common, there are currently no reports evaluating stealth vaping behaviour among e-cigarette users. The purpose of this study is to provide an overview of stealth vaping behaviour, including the frequency among experienced e-cigarette users and locations in which stealth vaping is most common.

METHODS

Participants

Participants in the current study were part of a longitudinal cohort study. Adult (≥18 years of age) e-cigarette users were invited to participate in an online survey from 2012 to 2015 about their use, device characteristics and related behaviours (baseline survey). A link to the baseline survey was posted on websites frequented by e-cigarette users, including e-cigarette-forum. com and the NJOY website. The details and the results of the baseline survey can be found in refs.22 23. At the completion of the baseline survey, those interested in participating in future research provided their contact information. In January 2017, 1863 participants who opted to provide their contact information were sent an email invitation with a unique link to complete a follow-up survey. Email reminders were sent up to four times on a weekly basis to those who did not yet complete the survey. After four email attempts, telephone calls were attempted for those who left a contact number. The current study uses data only collected from the follow-up survey.

Measures

Participants completed questionnaires about basic demographic information, e-cigarette frequency of use and current cigarette smoking status in the past 7 days (yes/no). E-cigarette dependence was measured by the Penn State Electronic Cigarette Dependence Index (PSECDI).22 One item of interest from the PSECDI was ‘Is it hard to keep from using an electronic cigarette in places where you are not supposed to? (yes/no)’.

To measure stealth vaping behaviours, participants were asked ‘Have you ever ‘stealth vaped’, that is to say, used an e-cigarette in a public place where it was not approved and attempted to conceal your e-cigarette use? (yes/no)’. Those who reported stealth vaping were asked how many days ago they last stealth vaped. Responses were coded into mutually exclusive groups: stealth vaped in the past 48 hours, stealth vaped in the past 3–7 days and stealth vaped more than a week ago. Participants were also asked to select the kinds of places they stealth vape from a list of options (at work, in school, at home, in restaurant, in bars/nightclubs, at the movies, other) and multiple selections were permitted. Those who selected ‘other’ were asked to describe the other kinds of places where they stealth vaped in an open text field. Responses were reviewed and manually coded into the following response groups: shopping, airplane/airport, events/activities, hospitals, other transportation and the bathroom. Participants were also asked ‘Do you have a smaller e-cig for use in public places where it may not be approved or where it would be difficult to use without inconveniencing others (yes/no)’. Finally, participants were asked if they have ever ‘used a liquid that had a substance other than nicotine (or zero nicotine) (yes/no)’.

Data collection and analysis

The survey data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) hosted at the Penn State Milton S Hershey Medical Center and College of Medicine. REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies.24 All data were analysed using SAS V.9.4. Participants included in the analysis were those who completed the follow-up survey and who reported current e-cigarette use in the past 30 days at the time of the survey and answered the questions pertaining to stealth vaping.

Means and frequencies were used to describe the sample and to examine the overall prevalence and frequency of stealth vaping, as well as to describe the locations most common for stealth vaping. χ2 tests were used to determine differences in proportions between groups. A logistic regression model with stepwise selection was used to predict stealth vaping behaviour (yes/no) with basic demographics (age, race, gender, education level), e-cigarette use days, cigarette smoking status, all individual scale items of the PSECDI, use of another substance in e-cigarette (yes/no) and use of a smaller e-cigarette device (yes/no) as covariates. In addition, a secondary logistic regression model predicting stealth vaping was run with the PSECDI total score as an independent variable, substituting for the individual scale items.

RESULTS

The study population was comprised of 462 experienced e-cigarette users, of whom 67.5% were male and 92.4% were white. The mean age of participants was 44.3 years. Most participants (89.2%) reported using their e-cigarette every day in the past 30 days and the mean PSECDI score was 8.3 (SD=3.9), indicating moderate dependence. The majority of the sample was comprised of current exclusive e-cigarette users (86.2%) who reported a history of cigarette smoking. A small proportion reported current cigarette smoking (10.8%). Those currently smoking cigarettes reported smoking an average of 4 out of the past 7 days with an average of 6.9 cigarettes smoked per day. The remainder of the sample was comprised of never cigarette smokers (3%); however, 21% of those never smokers had a history of other tobacco use. Of interest, 18.6% of the sample reported ever vaping a substance other than nicotine in their e-cigarette.

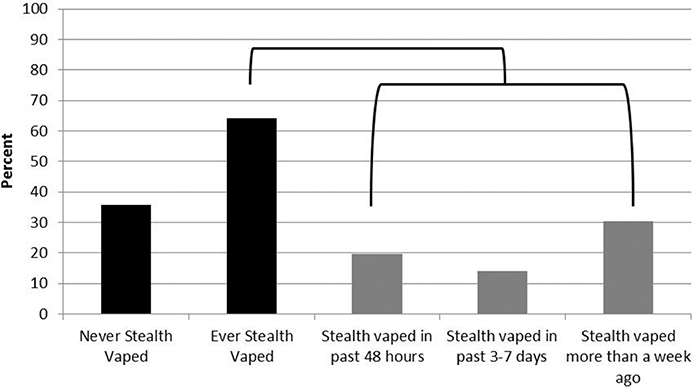

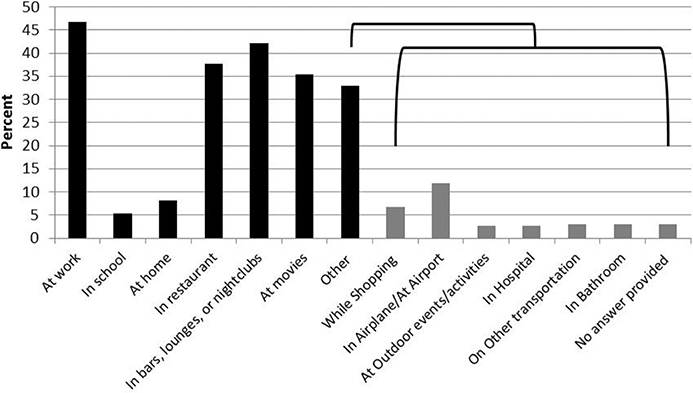

Overall, approximately two-thirds (64.3%, n=297) of the study population admitted to ever stealth vaping, and 31% of those who stealth vaped reported owning an additional smaller e-cigarette device solely to stealth vape or avoid bothering others while using. About one-third of those who stealth vaped (30.6%, n=91) did so in the past 48 hours, while 21.9% (n=65) reported stealth vaping in the past 7 days (but not in the past 48 hours), and the remainder reported last stealth vaping more than a week ago (figure 1). The most common places to stealth vape included at work (46.8%), followed by bars/nightclubs (42.1%), restaurants (37.7%), at the movies (35.4%) and other (33%). The most common ‘other’ responses included at the airport/on an airplane (11.8%, n=35/297) and while shopping (6.7%, n=20/297) (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of stealth vaping overall (n=462). Black brackets indicate results are part of a sub-sample.

Figure 2.

Common locations for stealth vaping among those who reported ever engaging in the behaviour (n=297). Black brackets indicate results are part of a sub-sample.

Predictors of stealth vaping included finding it difficult to refrain from using an e-cigarette in forbidden places (OR=4.9, 95% CI 2.2 to 10.7), owning a smaller device specifically for stealth vaping (OR=2.5, 95% CI 1.5 to 4.2), earlier time to first use of the day (OR=1.2, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.4) and greater number of use days in the past 30 days (OR=1.05, 95% CI 1.006 to 1.097). Use of another substance in the e-cigarette was not a significant predictor of stealth vaping in the model, and those who stealth vaped were not more likely than those who did not to use a substance other than nicotine (19.5% vs 17.0%, respectively; p=0.50). In addition, age was not a significant predictor of stealth vaping (59% of those aged <30 years stealth vaped vs 65.1% of aged ≥30 years stealth vaped; p=0.36). In the secondary model with the PSECDI total score included in place of the individual PSECDI scale items, the PSECDI total score (OR=1.2, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.22) and owning a device solely for stealth vaping (OR=2.4, 95% CI 1.5 to 4.0) were the only significant predictors of stealth vaping.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the stealth vaping behaviour among experienced e-cigarette users. Overall, we found almost two-thirds of e-cigarette users reported ever stealth vaping, and of those who reported ever stealth vaping, almost half reported having done so in the past week. Predictors of stealth vaping were related to reporting greater dependence and owning a smaller e-cigarette device solely for stealth vaping.

Approximately 31% of stealth vapers reported owning an additional smaller e-cigarette device solely to stealth vape or avoid bothering others while vaping. While users were not asked to report the type of e-cigarette device they used to stealth vape, it is important that in the future researchers evaluate the common types of devices being used for this behaviour. In August 2016, the US Food and Drug Administration gained regulatory authority over all tobacco products, including e-cigarettes, in order to reduce potential harms to consumers of tobacco products.25 Regulators should consider stealth vaping behaviours when implementing e-cigarette product design regulations since some e-cigarette device features may be more appealing to stealth vapers and manufacturers may intentionally design products to facilitate stealth vaping.

The most common places for stealth vaping included at work, bars/nightclubs, restaurants and at the movies. Of interest, our study found that a small proportion of stealth vapers reported doing so in an airport or airplane. While cigarette smoking and e-cigarette use on an aircraft is prohibited by the Department of Transportation,26 the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) instructs all passengers to carry e-cigarettes with them on the airplane27 due to the potential fire hazard created when packing a battery-powered e-cigarette in checked luggage. An unintended consequence of this FAA requirement is that it allows passengers to use their e-cigarettes when it is prohibited via stealth vaping.

Our study was also able to provide insight into concerns about the use of substances other than nicotine in e-cigarettes, like cannabis, and how vaping, and in particular stealth vaping, allows for the discreet use of other drugs.28 29 In the current study, participants were asked generally about the use of any substance other than nicotine in their e-cigarette. We found that 18.6% of the study population reported ever using a substance other than nicotine in their e-cigarette. A study of adult e-cigarette users which asked directly about the use of cannabis in e-cigarettes found a similar result; 17.8% of e-cigarette users reported lifetime vapourisation of cannabis. One of the main motivations for users to vapourise cannabis in that study was that vapourising can be concealed more easily compared with smoking.29 While it appears that the use of other substances in e-cigarettes does occur regularly, in the current study, using other substances in the e-cigarette was not predictive of stealth vaping and those who stealth vaped were not more likely to use a substance other than nicotine.

Although this study was able to identify the prevalence of and common locations for stealth vaping, much remains unknown about the behaviour. It can be hypothesised that beliefs about the harmlessness of e-cigarette aerosol15 18 30 or the greater dependence exhibited by stealth vapers could be reasons; however, there have been no studies to date examining user motivations for engaging in the behaviour. Additional research is needed to understand motivations to stealth vape and the impact of stealth vaping on sustaining nicotine addiction. Furthermore, research is needed to understand the impacts of stealth vaping on toxicant exposure and user health. For example, stealth vapers have reported on online forums a unique inhalation pattern and have reported holding the aerosol in their lungs to allow for dissipation before exhalation.13 It remains unknown if the deep lung hit or the prolonged exposure to e-cigarette aerosol in the lung impacts toxicant exposure or health effects related to use.

The participants in this study were experienced long-term e-cigarette users who voluntarily chose to participate in a survey on e-cigarette use. It is possible that these users may have different stealth vaping behaviours compared with new e-cigarette users or users not willing to complete a survey on e-cigarette use. It is also possible that users under-reported stealth vaping behaviours because the behaviour may not be considered socially acceptable. In addition, while information was collected about the locations where users most commonly stealth vaped, we did not collect data on how often users frequented each location; thus, we were unable to determine if stealth vaping was related to time spent at a location. Finally, this study was conducted only among adults 18 years of age and older. More research is needed to understand the prevalence, reasons for and impacts of stealth vaping among youth.

In conclusion, these findings suggest that stealth vaping is a common behaviour for many experienced e-cigarette users. About half of those who reported stealth vaping did so in the past week, most commonly at work, bars/nightclubs, restaurants and at the movies. E-cigarette dependence was a significant predictor of stealth vaping, indicating that those who stealth vaped were more dependent and that stealth vaping may be a way for users to sustain their nicotine addiction.

What this paper adds.

What is already known on this subject

Anecdotal evidence suggests that stealth vaping is a common behaviour among e-cigarette users.

What important gaps in knowledge exist on this topic

Although preliminary evidence suggests that stealth vaping is common, there are no studies detailing the behaviour.

What this paper adds

This study identified that the majority of experienced e-cigarette users have stealth vaped, which could have impact on e-cigarette user health, bystander health, public safety and e-cigarette product regulation.

Funding

The authors are partly supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health and the Center for Tobacco Products of the US Food and Drug Administration (under award number P50-DA-036107). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Food and Drug Administration.

Footnotes

Competing interests JF has done paid consulting for pharmaceutical companies involved in producing smoking cessation medications, including GSK, Pfizer, Novartis, J&J and Cypress Bioscience, and received a research grant from Pfizer. There are no competing interests to declare for other authors.

Patient consent Obtained.

Ethics approval This study was approved by the Penn State University College of Medicine Institutional Review Board, Hershey.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. Smoke-free laws encourage smokers to quit and discourage youth from starting. 2017. https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/factsheets/0198.pdf

- 2.Hyland A, Barnoya J, Corral JE. Smoke-free air policies: past, present and future. Tob Control 2012;21:154–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Nonsmokers' Rights Foundation. Smokefree Lists, Maps, and Data. 2018. http://www.no-smoke.org/goingsmokefree.php?id=519

- 4.QuickStats: percentage of adults who ever used an e-cigarette and percentage who currently use e-cigarettes, by age group - National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMillen RC, Gottlieb MA, Shaefer RM, et al. Trends in electronic cigarette use among U.S. adults: use is increasing in both smokers and nonsmokers. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:1195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marynak K, Kenemer B, King BA, et al. State laws regarding indoor public use, retail sales, and prices of electronic cigarettes - U.S. States, Guam, Puerto Rico, and U.S. Virgin Islands. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;2017:1341–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gourdet CK, Chriqui JF, Chaloupka FJ. A baseline understanding of state laws governing e-cigarettes. Tob Control 2014;23 Suppl 3:iii37–iii40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paradise J Electronic cigarettes: smoke-free laws, sale restrictions, and the public health. Am J Public Health 2014; 104:e17–e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.New York Public Health Law 1399-o. 2017. http://www.assembly.state.ny.us/leg/?default_fld=&bn=S02543&term=&Summary=Y&Memo=Y&Text=Y

- 10.Yingst JM, Veldheer S, Hammett E, et al. Should electronic cigarette use be covered by clean indoor air laws? Tob Control 2017;26:e16–e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones I Stealth Vaping: How to become a vaping ninja. 2016. http://vaping360.com/stealth-vaping/

- 12.Stealth Vape. 2017. https://www.e-cigarette-forum.com/threads/stealth-vape.794817/

- 13.Jones I. Vaping and inhaling: everything you need to know. 2017. http://vaping360.com/vaping-and-inhaling-everything-you-need-to-know/ (updated 13 Mar 2018).

- 14.Everything you need to know about stealth vaping. 2017. https://www.vapingzone.com/blog/stealth-vaping-techniques/

- 15.Farrimond H E-cigarette regulation and policy: UK vapers' perspectives. Addiction 2016;111:1077–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters RJ, Meshack A, Lin MT, et al. The social norms and beliefs of teenage male electronic cigarette use. J Ethn Subst Abuse 2013;12:300–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammal F, Finegan BA. Exploring attitudes of children 12–17 years of age toward electronic Cigarettes. J Community Health 2016;41:962–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagoner KG, Cornacchione J, Wiseman KD, et al. E-cigarettes, hookah pens and vapes: adolescent and young adult perceptions of electronic nicotine delivery systems: Table 1. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2016;18:2006–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Public Health Consequences of e-cigarettes. Washington DC: National Academies of Science, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson N, Hoek J, Thomson G, et al. Should e-cigarette use be included in indoor smoking bans? Bull World Health Organ 2017;95:540–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fairchild AL, Bayer R, Colgrove J. The renormalization of smoking? E-cigarettes and the tobacco "endgame". N Engl J Med 2014;370:293–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foulds J, Veldheer S, Yingst J, et al. Development of a questionnaire for assessing dependence on electronic cigarettes among a large sample of ex-smoking E-cigarette users. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:186–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yingst JM, Veldheer S, Hrabovsky S, et al. Factors associated with electronic cigarette users’ device preferences and transition from first generation to advanced generation devices. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:1242–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA News Release: FDA takes significant steps to protect Americans from dangers of tobacco through new regulation. 2016. https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm499234.htm

- 26.Proposed Rule: smoking of electronic cigarettes on aircraft. 2011. https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=DOT-OST-2011-0044-0003

- 27.Federal Aviation Administration. Pack safe: Electornic cigarettes, 2013. vaping devices.

- 28.Blundell M, Dargan P, Wood D. A cloud on the horizon-a survey into the use of electronic vaping devices for recreational drug and new psychoactive substance (NPS) administration. QJM 2018;111:9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morean ME, Lipshie N, Josephson M, et al. Predictors of Adult e-cigarette users vaporizing cannabis using e-cigarettes and vape-pens. Subst Use Misuse 2017;52:974–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cummings M, Break D, Nahhas G, et al. About vaping in home and smoke-free public placesL Findings from the ITC 4 Country project. Society for research on nicotine and tobacco. Baltimore MD: 2018. [Google Scholar]