Abstract

Temporal bone malignancies are relatively uncommon tumors. Their location adjacent to vital structures such as the carotid artery, jugular vein, otic capsule, and temporal lobe can make their treatment potentially challenging. The purpose of this study was to compare outcomes in temporal bone malignancies obtained via pooled literature data.

The study sought to examine factors affecting survival in temporal bone malignancies based on the studies in the existing published literature. A systematic search was conducted on the PubMed (Medline), Embase, and Google Scholar databases to identify relevant studies from 1951 to 2022 that described the treatment of temporal bone malignancies. Articles that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were assessed and analyzed by the author.

The literature search identified 5875 case series and case reports, and 161 of them contained sufficient data to be included in the pooled data analysis, involving a total of 825 patients. Multivariate analysis of the pooled literature data showed that overall stage, presence of facial palsy, and surgical margin status significantly affected overall survival (OS), while overall stage and presence of facial palsy significantly affected disease-free survival (DFS).

To summarize, this study examined pooled survival data on demographics, treatment, and survival of patients with temporal bone malignancies utilizing an extensive literature-based pooled data meta-analysis. Overall stage, facial nerve status, and surgical margin status appeared to most strongly affect survival in patients with temporal bone malignancies.

Keywords: survival, oncology, head and neck, ear, cancer

Introduction and background

The temporal bone is a relatively rare site of malignancy. Ear canal or middle ear cancers affect approximately one patient per million each year, and temporal bone cancers account for approximately only 0.2% of all head and neck cancers [1]. These patients tend to be older, especially patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone. The common symptoms can include otalgia, otorrhea, hearing loss, and more ominously, facial palsy. Squamous cell carcinoma is typically the most common histopathological type found in temporal bone cancer. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment, with adjuvant radiation provided in addition to surgery for advanced disease. Patient survival is typically lower in patients with tumors of a higher stage and higher grade, those with positive surgical margins, and locoregional or distant spread [1]. Given the relative rarity of temporal bone malignancies, a pooled data analysis of cases reported in the literature may be a useful tool for studying patient and tumor characteristics affecting survival in these patients. Hence, this study sought to evaluate patient demographics and survival outcomes for patients with temporal bone malignancies documented in the literature from 1951 to 2022 and to analyze the demographics, treatment, and survival data found therein.

Review

Review of the literature

Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria, a systematic search of the PubMed (Medline), Embase, and Google Scholar databases was conducted [2]. The following search terms were employed: “temporal bone + cancer + malignant + carcinoma”. The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for Case-Control Studies was utilized to assess the included studies [3]. Studies were included if they were published in any language in scientific journals published in the PubMed (Medline), Embase, and Google Scholar databases, and reported data on human subjects with newly diagnosed and previously untreated primary solid temporal bone malignancies (hematologic malignancies, metastases to the temporal bone or local spread to the temporal bone from primary parotid malignancies, and recurrent tumors previously treated were excluded), with sufficient individual patient data on overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS).

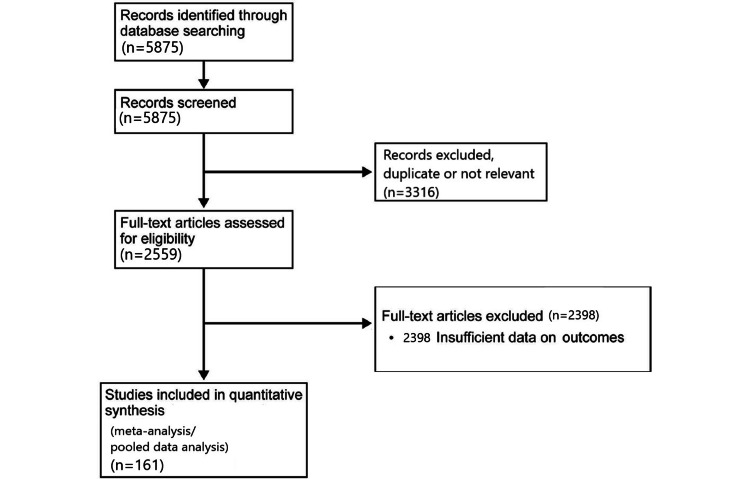

The literature search was conducted from February 1 to 28, 2022. The titles and abstracts of the articles were reviewed and articles with duplicate or irrelevant data were excluded. The remaining articles were reviewed in full by the author and articles with sufficient and relevant individual patent data on temporal bone malignancies were included in the pooled data analysis. The individual patient data on OS and DFS, overall and tumor (T), nodal (N), and metastasis (M) stages, solid tumor type, age at diagnosis, treatment type, surgery type if applicable, presence of hearing loss and presence of facial nerve palsy at diagnosis, and surgical margin status if applicable were compiled into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Washington, USA) for the 161 studies included in the pooled data analysis [4-165]. The search for studies that spanned the period from 1951 to 2022 yielded a total of 5875 articles. After excluding articles not related to primary human temporal bone malignancies (animal studies, basic science/in vitro studies, etc.), 2559 articles were assessed for the availability of individual patient data. Applying these exclusion criteria yielded 161 articles with individual patient data on primary temporal bone malignancies involving 835 patients, 825 of whom had full analyzable survival data. The data were compiled and checked by the author for accuracy. Figure 1 illustrates the PRISMA selection process for the literature pooled data analysis.

Figure 1. PRISMA study selection flow diagram for the systematic literature search.

PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

The staging was performed using the Modified Pittsburgh Staging System for temporal bone malignancies [165,166]. The primary survival outcomes were OS and DFS at 60 months. Survival outcomes were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier/log-rank method. Statistical analysis was performed using XLSTAT Biomed (Addinsoft, New York, NY/Paris, France). Linear regression was used to perform multivariate analysis. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Fisher’s exact test was used to determine odds ratios.

Results

Pooled Data Meta-Analysis: Demographics

The pooled data meta-analysis identified 161 studies with individual patient data involving 835 patients, with 825 having analyzable OS and DFS data. Patient sex was unknown in 333 of 825 (40.4%) patients, while 237 (28.7%) were female and 255 (30.9%) were male. The average patient age was 54 ±23 years. Of the 825 patients with analyzable survival data, 621 had squamous cell carcinoma (75.2%), 126 had sarcoma (15.3%), 27 had adenocarcinoma (3.3%), 19 had basal cell carcinoma (2.3%), nine had mucoepidermoid carcinoma (1.1%), 10 had adenoid cystic carcinoma (1.2%), and 13 had melanoma (1.6%).

Of the 825 patients with analyzable survival data, there were 113 stage I (13.7%), 88 stage II (10.7%), 210 stage III (25.5%), 342 stage IV (41.5%), and 72 unknown stage patients (8.7%). There were 167 T1 (20.2%), 150 T2 (18.2%), 190 T3 (23.0%), 277 T4 (33.6%), and 41 unknown T stage (5.0%) patients. The cohort included 608 N0 (73.7%), 55 N1 (6.7%), 40 N2 (4.8%), 5 N3 (0.6%), and 117 unknown N stage (14.2%) patients. There were 656 M0 (79.5%), 55 M1 (6.7%), and 114 unknown M stage (13.8%) patients.

Pooled Data Meta-Analysis: Patient Presentation

In 661 of 825 patients (80.1%), hearing loss status was unknown, while in the 164 (19.9%) patients whose hearing loss status was known, 109 had hearing loss (66.5%) and 55 did not have hearing loss (33.5%). Facial nerve status was unknown in 564 of 825 patients (68.4%). Of the remaining 261 patients (31.6%) in whom the presence or absence of facial palsy was specified, 107 (41.0%) had some degree of facial palsy while 154 (59.0%) had normal facial nerve function.

Pooled Data Meta-Analysis: Treatment and Pathology

Surgical margin status was known in 313 of 825 patients (37.9%); 131 of 313 had positive margins (41.9%) and 182 had negative margins (58.1%). The remaining patients were either treated nonsurgically (203, 24.6%), or their margin status was unknown (309, 37.5%). Tumor grade was unknown in 728 of 825 patients (88.2%), low grade/well-differentiated in 47 (5.7%), intermediate grade/moderately differentiated in 28 (3.4%), and high grade/poorly differentiated in 22 (2.7%). Of the patients for whom the treatment type was known, 59 (7.2%) were treated with surgery + radiation + chemotherapy, 330 (40.0%) were treated with surgery + radiation, 90 (10.9%) were treated with radiation + chemotherapy, 21 (2.5%) with surgery + chemotherapy, five (0.6%) with chemotherapy alone, 155 (18.8%) with surgery alone, and 98 (11.9%) with radiation alone. The treatment type was none in 10 patients (1.2%) and unknown in the remaining 57 patients (6.9%).

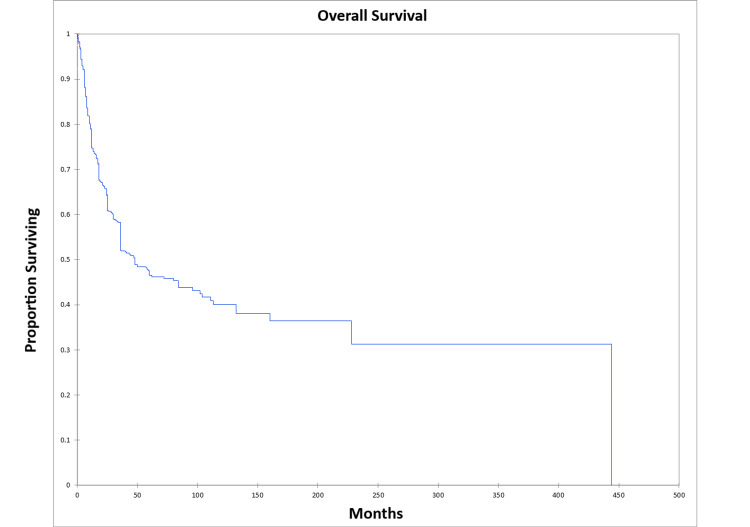

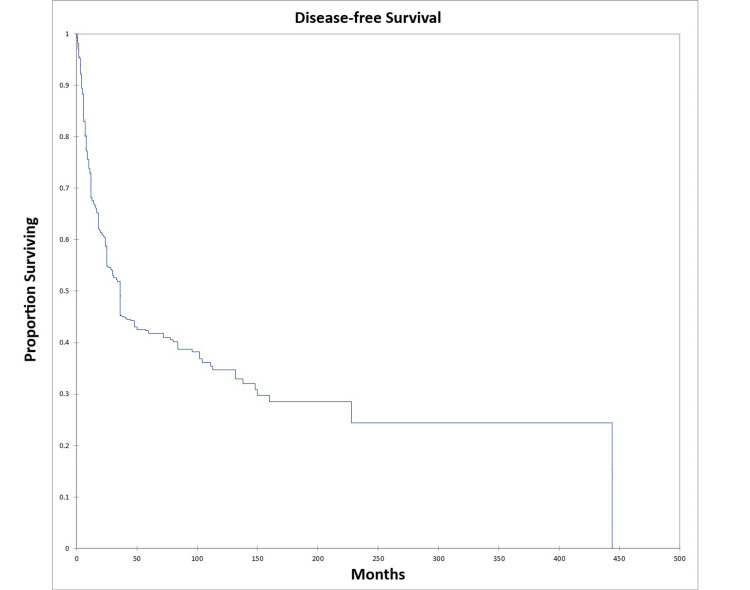

OS at five and 10 years was 46.0% and 39.0% respectively for the entire cohort. DFS at five and 10 years was 41.0% and 34.0% respectively for the entire cohort. Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier OS for the entire cohort, while Figure 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier DFS for the entire cohort.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier overall survival for the entire literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier disease-free survival for the entire literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

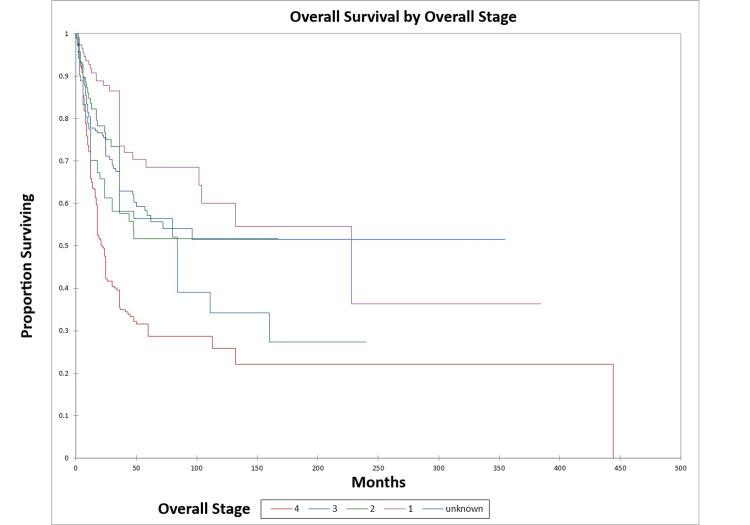

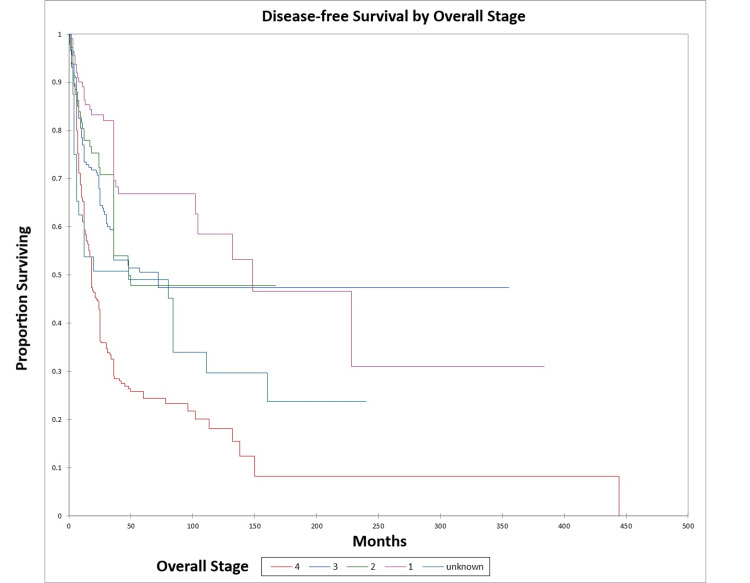

Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate the Kaplan-Meier OS (p<0.0001) and DFS (p<0.0001) respectively by overall stage.

Figure 4. Kaplan-Meier overall survival by overall stage for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

Figure 5. Kaplan-Meier disease-free survival by overall stage for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

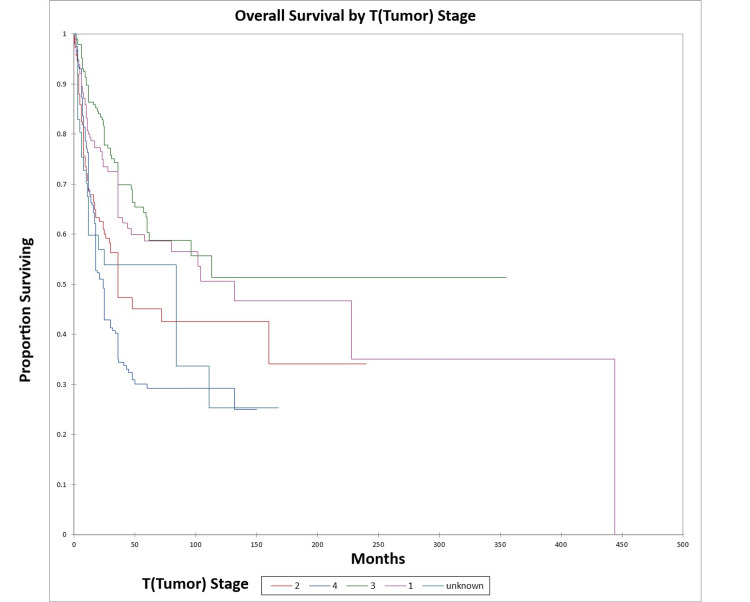

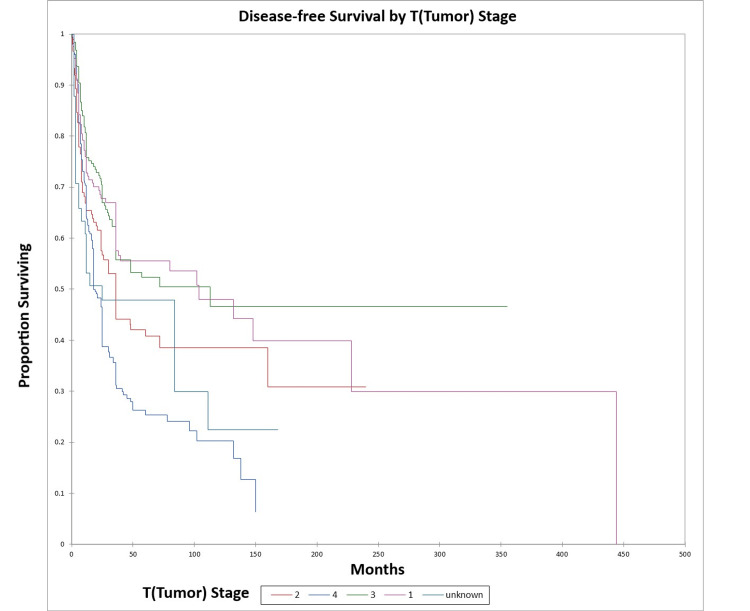

Figure 6 and Figure 7 illustrate the Kaplan-Meier OS (p<0.0001) and DFS (p<0.0001) respectively by T (tumor) stage.

Figure 6. Kaplan-Meier overall survival by T (tumor) stage for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

Figure 7. Kaplan-Meier disease-free survival by T (tumor) stage for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

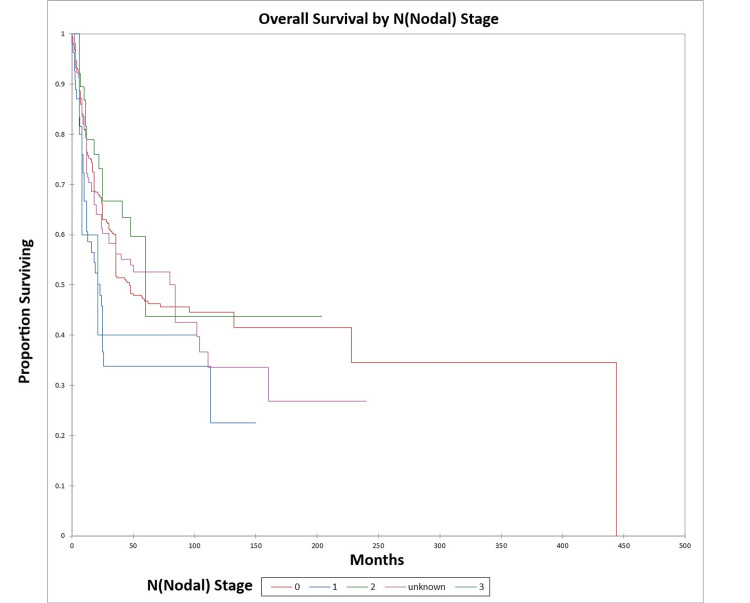

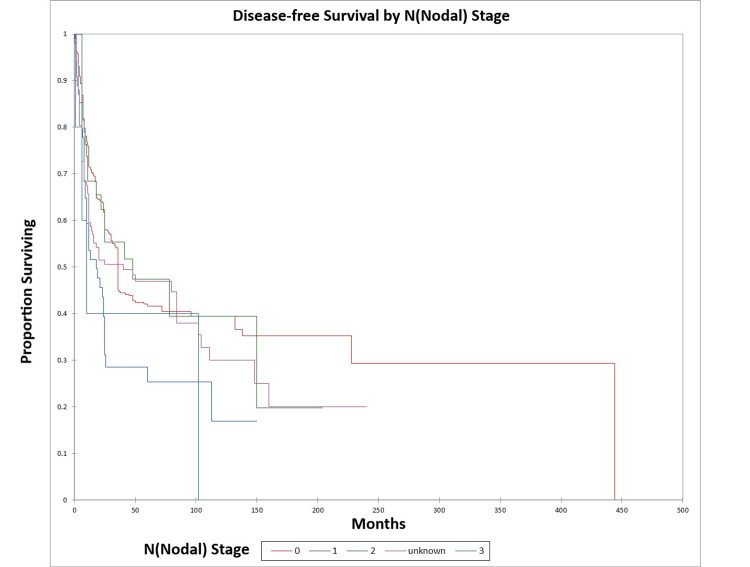

Figure 8 and Figure 9 illustrate the Kaplan-Meier OS (p=0.04) and DFS (p=0.01) respectively by N (nodal) stage.

Figure 8. Kaplan-Meier overall survival by N (nodal) stage for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

Figure 9. Kaplan-Meier disease-free survival by N (nodal) stage for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

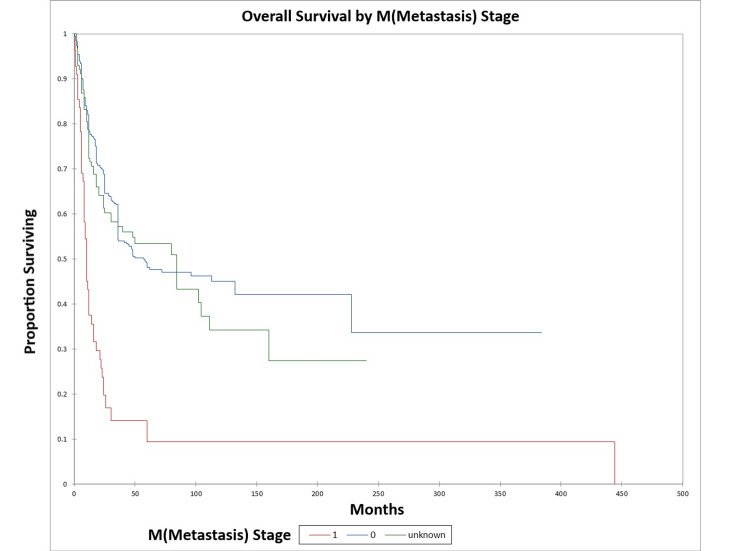

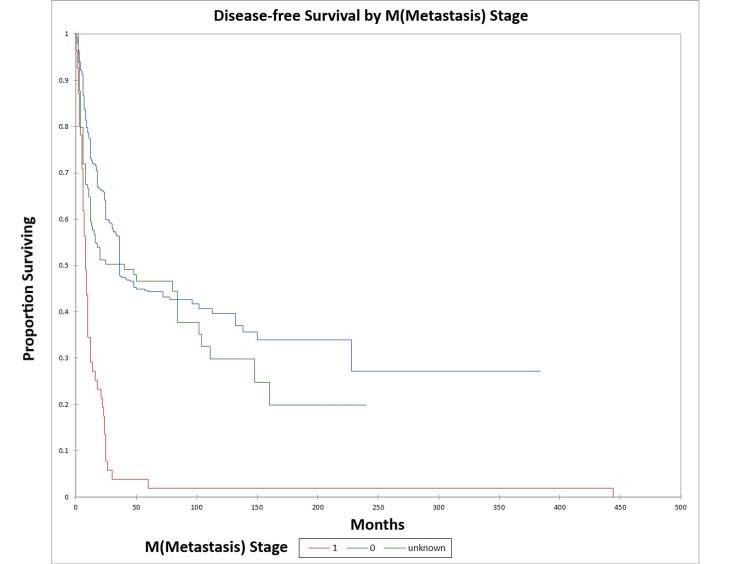

Figure 10 and Figure 11 illustrate the Kaplan-Meier OS (p<0.0001) and DFS (p<0.0001) respectively by M (metastasis) stage. The odds ratio for death at five years for M1 patients vs. M0 patients was 9.6 [95% confidence interval (CI): 3.8-24.3) (OS)], and 44.1 (95% CI: 6.1-321.0) (DFS).

Figure 10. Kaplan-Meier overall survival by M (metastasis) stage for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

Figure 11. Kaplan-Meier disease-free survival by M (metastasis) stage for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

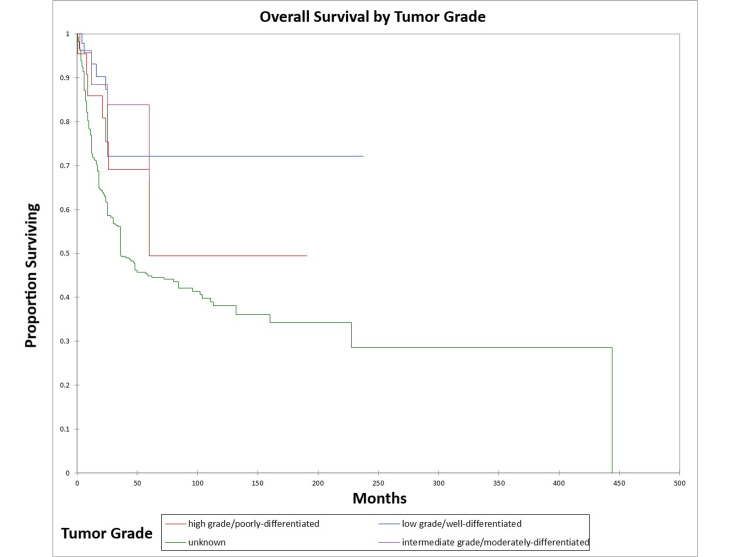

Figure 12 and Figure 13 illustrate the Kaplan-Meier OS (p=0.002) and DFS (p=0.06) respectively by tumor grade.

Figure 12. Kaplan-Meier overall survival by tumor grade for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

Figure 13. Kaplan-Meier disease-free survival by tumor grade for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

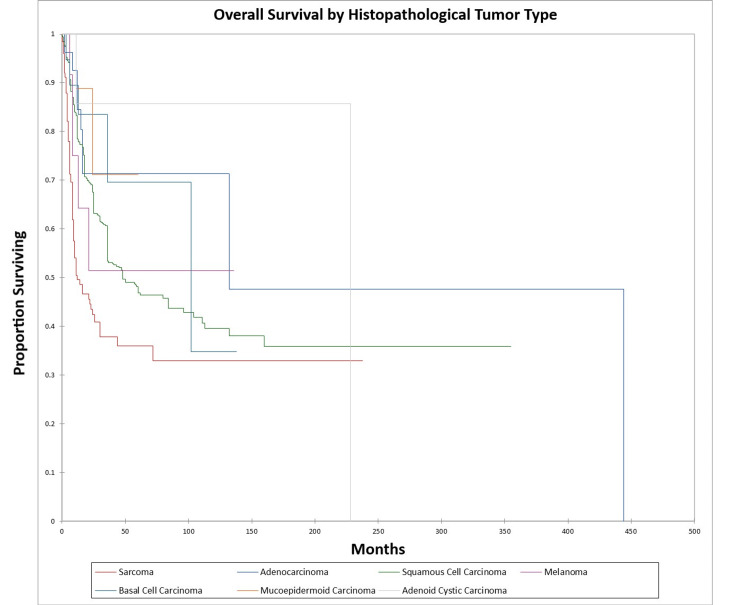

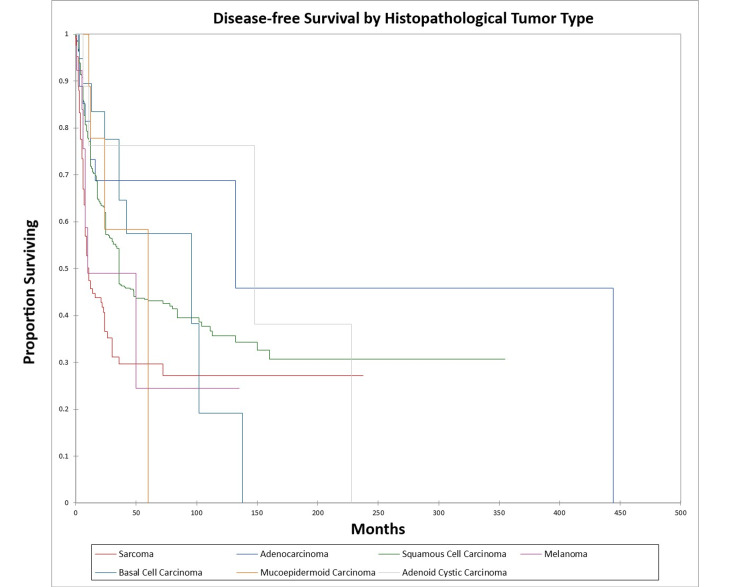

Figure 14 and Figure 15 illustrate the Kaplan-Meier OS (p<0.0001) and DFS (p<0.0001) respectively by histopathological tumor type. OS and DFS were highest for adenocarcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma, and lowest for squamous cell carcinoma, sarcoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, and melanoma.

Figure 14. Kaplan-Meier overall survival by histopathological type for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

Figure 15. Kaplan-Meier disease-free survival by histopathological type for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

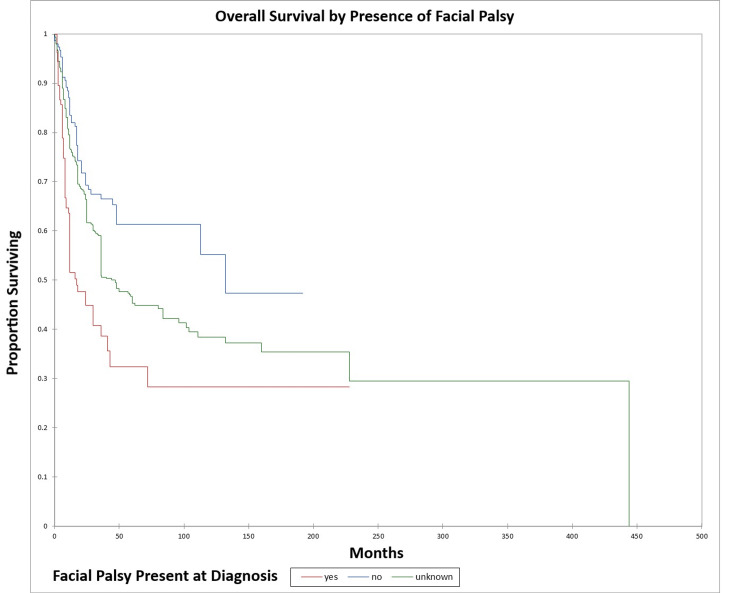

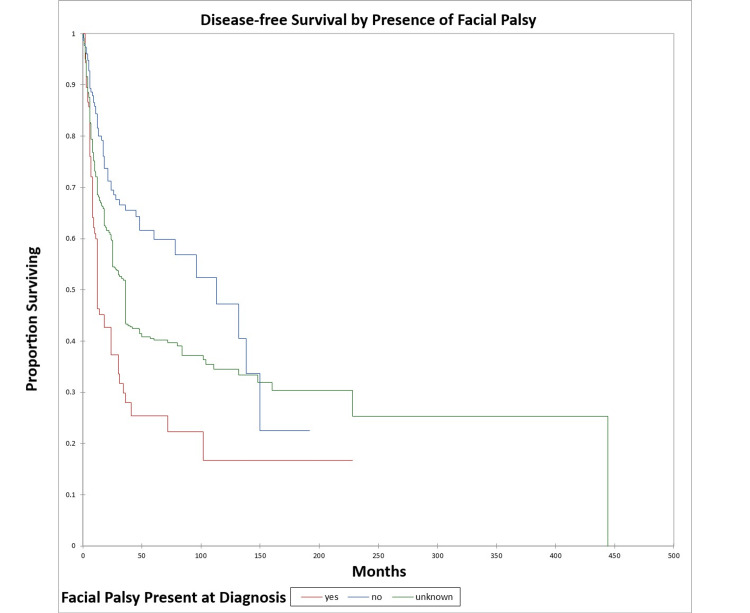

Figure 16 and Figure 17 illustrate the Kaplan-Meier OS (p<0.0001) and DFS (p<0.0001) respectively by the presence or absence of facial nerve palsy. The odds ratio for death at five years for patients with facial palsy vs. patients without facial palsy was 3.5 (95% CI: 2.1-5.8) (OS) and 4.3 (95% CI: 2.5-7.4) (DFS).

Figure 16. Kaplan-Meier overall survival by the presence or absence of facial palsy for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

Figure 17. Kaplan-Meier disease-free survival by the presence or absence of facial palsy for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

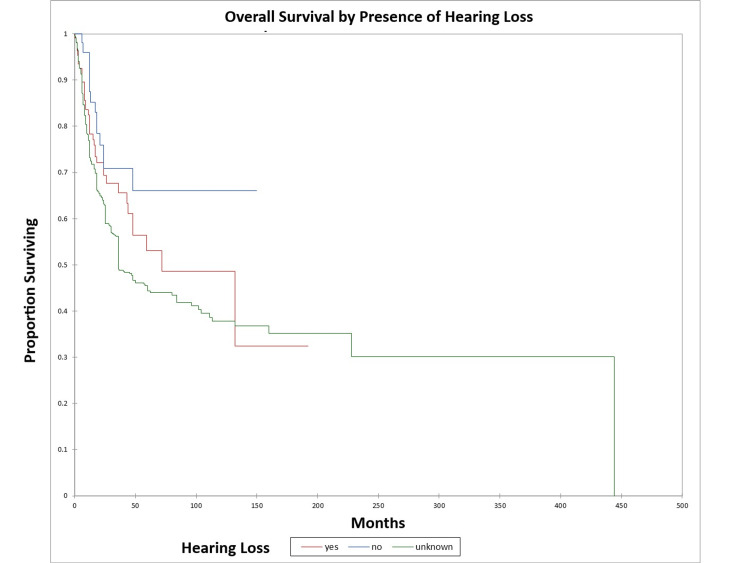

Figure 18 and Figure 19 illustrate the Kaplan-Meier OS (p=0.02) and DFS (p=0.003) respectively by the presence or absence of hearing loss. The odds ratio for death at five years for patients with hearing loss vs. patients with normal hearing was 1.73 (95% CI: 0.9-3.4) (OS) and 2.8 (95% CI: 1.4-5.5) (DFS).

Figure 18. Kaplan-Meier overall survival by the presence or absence of hearing loss for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

Figure 19. Kaplan-Meier disease-free survival by the presence or absence of hearing loss for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

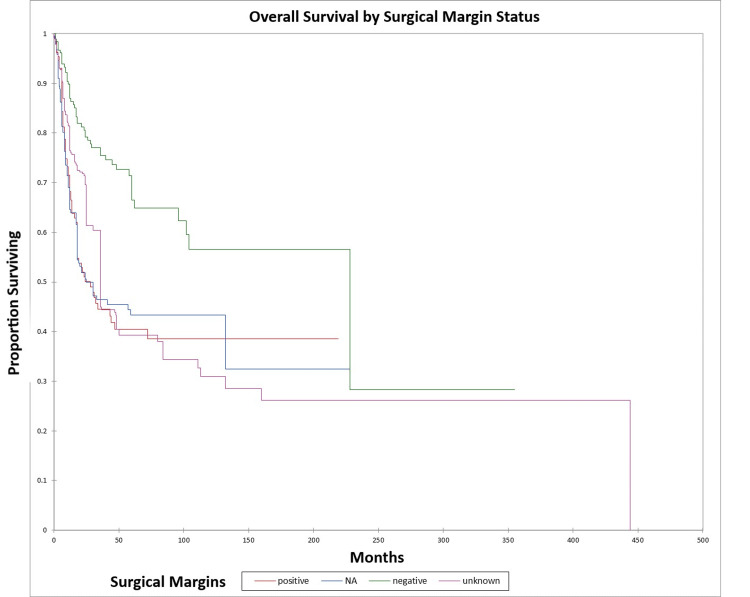

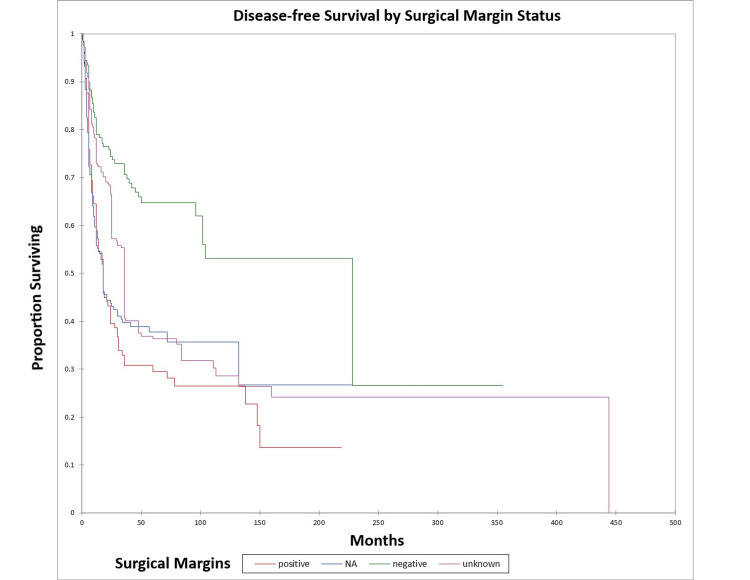

Figure 20 and Figure 21 illustrate the Kaplan-Meier OS (p<0.0001) and DFS (p<0.0001) respectively by margin status. The odds ratio for death at five years for patients with positive margins vs. patients with negative margins was 3.7 (95% CI: 2.3-5.9) (OS) and 4.5 (95% CI: 2.7-7.3) (DFS).

Figure 20. Kaplan-Meier overall survival by margin status for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

NA: not applicable

Figure 21. Kaplan-Meier disease-free survival by margin status for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

NA: not applicable

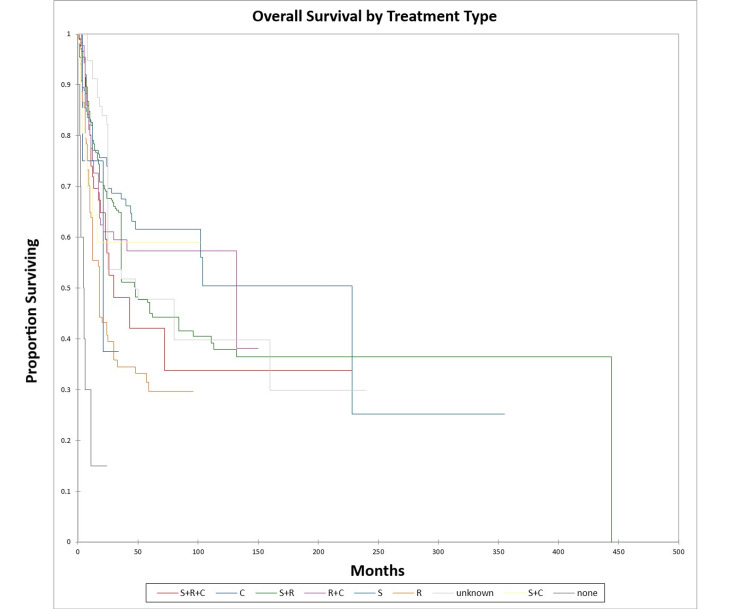

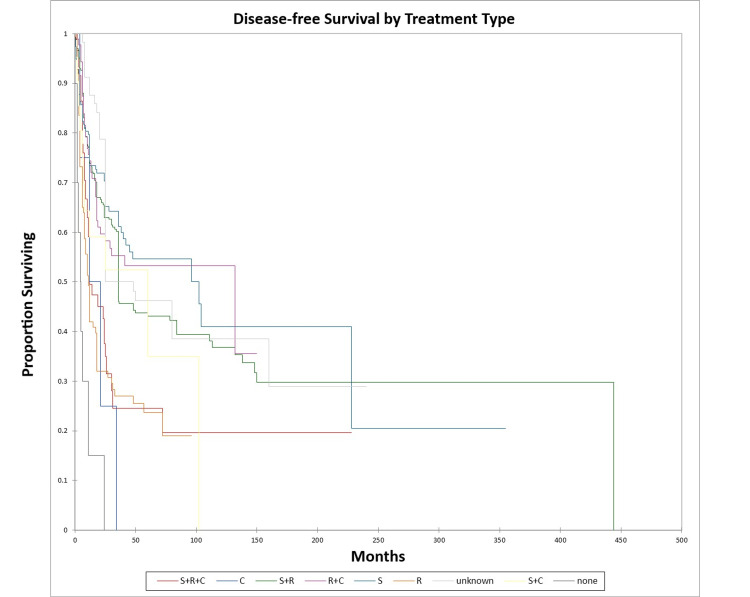

Figure 22 and Figure 23 illustrate the Kaplan-Meier OS (p<0.0001) and DFS (p<0.0001) respectively by treatment type.

Figure 22. Kaplan-Meier overall survival by treatment type for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

S: surgery; R: radiation; C: chemotherapy

Figure 23. Kaplan-Meier disease-free survival by treatment type for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

S: surgery; R: radiation; C: chemotherapy

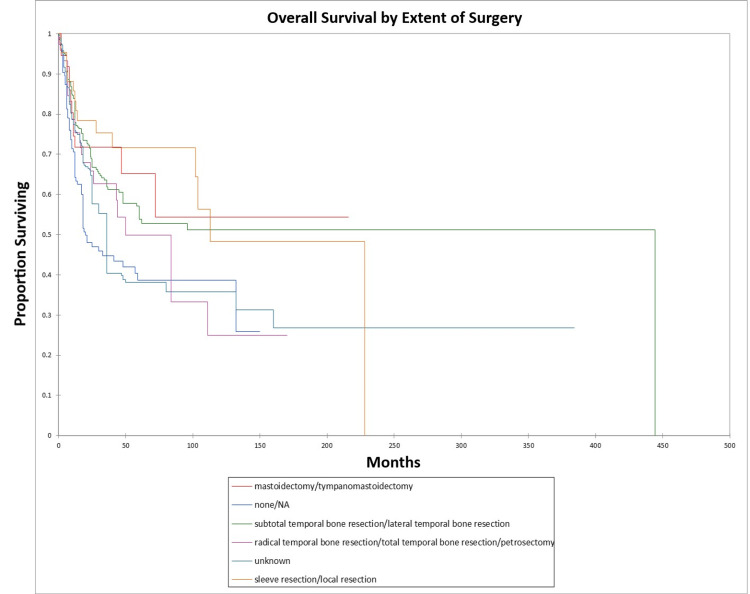

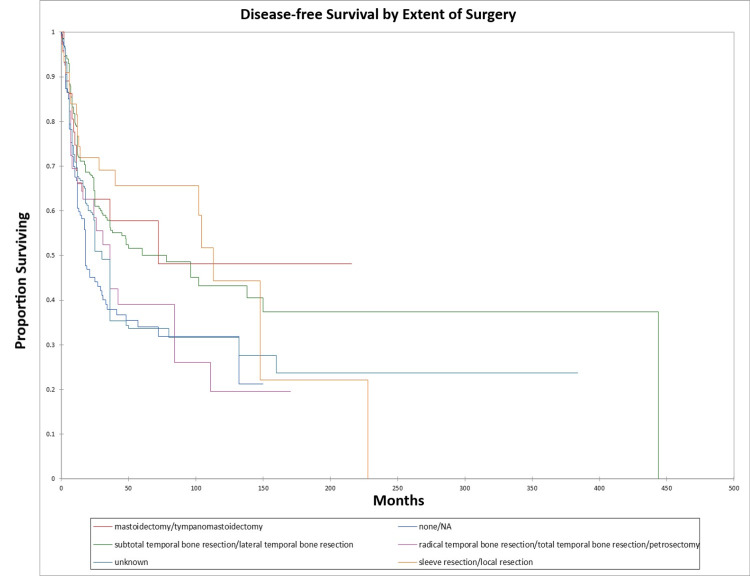

Figure 24 and Figure 25 illustrate the Kaplan-Meier OS (p=0.0002) and DFS (p=0.0003) respectively by type of surgery performed.

Figure 24. Kaplan-Meier overall survival by type of surgery for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

Figure 25. Kaplan-Meier disease-free survival by type of surgery for literature-based temporal bone malignancy cohort.

Multivariate analysis demonstrated that only overall stage (p<0.0001), the presence or absence of facial palsy (p<0.0001), and surgical margin status (p=0.04) significantly affected OS, and only overall stage (p<0.0001) and the presence or absence of facial palsy (p=0.002) significantly affected DFS.

This study examined data on temporal bone malignancies based on a pooled data analysis of the literature on temporal bone cancers from 1951 to 2022. OS at five years was 46.0% for the entire literature-based cohort. The study included roughly equal numbers of male and female patients [sex unknown for 333/825 (40.4%) patients, while 237/825 were female (28.7%) and 255/825 were male (30.9%)]. The average patient age was 54 ±23 years. Squamous cell carcinoma was by far the most common histopathological type [621 of 825 patients (75.2%)], followed by sarcoma (126/825, 15.3%). Patients tended to present at a relatively advanced stage with 210/825 (25.5%) being stage III and 342/825 being stage IV (41.5%) at presentation, while only 113/825 (13.7%) were stage I and only 88/825 (10.7%) were stage II. The stage at presentation was unknown in 72/825 (8.7%). Nodal metastasis was relatively uncommon, with the cohort including 608/825 N0 (73.7%) patients and 100/825 (12.1%) N+ patients, with N stage unknown in 117/825 (14.2%) patients. Distant metastasis was also relatively uncommon with 656/825 (79.5%) M0 patients, 55/825 (6.7%) M1 patients, with M stage unknown in 114/825 (13.8%) patients. Patients treated with surgery alone (61.0% five-year OS/55.0% five-year DFS) had similar survival to patients treated with radiation + chemotherapy (58.0% five-year OS/53% five-year DFS) and patients treated with surgery + chemotherapy (59% five-year OS/52% DFS). Survival was somewhat lower for patients treated with radiation alone (32% five-year OS/25% five-year DFS) and patients treated with surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy (42% five-year OS/25% five-year DFS). This difference was significant on univariate analysis but not multivariate analysis. Treatment differences vary based on protocols at different centers, surgeon preference, and patient status/preference.

In the cohort, only the overall stage, presence or absence of facial palsy, and margin status significantly affected OS on multivariate analysis, while the overall stage and presence or absence of facial palsy significantly affected DFS. Survival was higher for adenocarcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma patients and lower for squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, and sarcoma patients, a difference that was significant on univariate analysis but not multivariate analysis. The finding that facial nerve palsy significantly affects survival even on multivariate analysis confirms the results of the Pittsburgh group that patients with facial nerve palsy have survival patterns that most closely align with the T4 group [165-167]. The overall stage was a significant predictor of OS and DFS on multivariate analysis. Lechner et al. similarly noted that stage was a significant predictor of survival in their literature-based analysis of patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone [168]. The finding that negative margins significantly improve OS on multivariate analysis is of note and unsurprising. The study by Wierzbicka et al. in 2017 also noted that positive margins significantly affected survival in temporal bone cancer patients [169]. Seligman et al. found that patients with temporal bone carcinoma had improved survival when patients had basal cell carcinoma, lateral temporal bone resection as opposed to subtotal temporal bone resection, were immunocompetent, and had no evidence of perineural or lymphovascular invasion [155]. Interestingly, in the present study, basal cell carcinoma patients had better OS and DFS than patients with squamous cell carcinoma at five years, but not at 10 years (69.0% and 34% five-year and 10-year OS and 58.0% and 19.0% five-year and 10-year DFS for basal cell carcinoma vs. 45.0% and 39.0% five-year and 10-year OS and 43.0% and 35.0% five-year and 10-year DFS for squamous cell carcinoma). This difference was significant on univariate but not multivariate analysis in the present study. Additionally, in the present study patients with adenocarcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma had better OS and DFS than basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma patients on univariate analysis.

In the present study, subtotal temporal bone resection was grouped with lateral temporal bone resection in the statistical analysis. In general, at time points less than 120 months, patients who had sleeve/local resection or mastoidectomy had better survival than patients who underwent no surgery, patients who underwent subtotal or lateral temporal bone resection, or patients who underwent radical or total temporal bone resection or petrosectomy. The extent of resection may act as a surrogate for stage and/or resectability and may greatly be affected by surgeon preference, patient health/comorbidities, or differences in surgical technique at various centers [124]. In the present study, survival differences by the extent of surgery/surgery type were significant on univariate but not multivariate analysis. That extent of resection may act as a surrogate for the stage is borne out by the finding that in the present study, local excision/sleeve resection was essentially only used for T1/stage I patients. Shiga et al. retrospectively examined 23 patients treated for cancer of the temporal bone using concomitant chemoradiotherapy from 2001 to 2014 using docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil in addition to radiotherapy [7]. They noted disease-specific five-year survival rates of 84.9% for the entire cohort, 100% for stage I, II, and III patients, and 75.5% for stage IV patients. Five-year survival in the present study was lower than the Shiga study for the entire literature cohorts, which may reflect the difference in sample size, or advances in treatment and survival in the years since the earlier patients treated in the literature cohort vs. the much more recent patients included in the Shiga study [7].

Nam et al. examined 26 patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the external auditory canal [170]. Similar to the present study, they noted that the T stage and overall stage significantly affected survival. The present study emphasizes the importance of accurate staging and, in patients treated surgically, negative surgical margins whenever possible. Acharya et al. examined The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database for cases of carcinomas of the middle ear between 1975 and 2016, while Gurgel et al. examined the SEER database for patients diagnosed with middle ear carcinoma between 1973 and 2004 [171,172]. The Gurgel et al. study noted that the five-year OS rate for 215 patients with middle ear cancer was 36.4%, while the five-year overall survival rate for T3 patients (which would include patients with middle ear cancer) in the present study was 63% [172]. Interestingly, similar to the present study, the Gurgel study observed that patients with adenocarcinoma had improved OS vs. other histopathological types [172]. Squamous cell carcinoma was the most common pathological subtype identified in the present study, consistent with squamous cell carcinoma being the most common pathological subtype seen in head and neck cancer patients [173].

This study has several limitations. The retrospective nature of the literature-based cohort makes selection and recall bias a possibility. Additionally, the fact that the period studied spanned more than 50 years (1951-2022) means that the study had to incorporate various differences in treatment preferences over time as treatment protocols and technology evolved. Additionally, the cohort comprised patients from several different countries, which may also introduce differences in treatment preferences, patient demographics, etc. However, despite these shortcomings, the very granular data drawn from the cohort (facial nerve and hearing loss status, surgical margin status, histopathological type, etc.) is highly invaluable and allows for a detailed retrospective analysis of the patient factors and their relationship with OS and DFS in the patients in the cohort.

Conclusions

This study retrospectively examined data on demographics, treatment, and survival of patients with temporal bone malignancies as per a literature-based pooled data analysis. Of note, overall stage and facial nerve status were significant predictors of OS and DFS on multivariate analysis, and surgical margin status significantly affected OS on multivariate analysis. Patient stage (overall and T, N, and M individual stages), surgical margin status, facial nerve palsy, hearing loss, treatment type, and histopathological type all appeared to significantly impact OS and DFS on univariate analysis.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Temporal bone malignancies. Gidley PW, DeMonte F. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2013;24:97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. PLoS Med. 2009;6:0. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Stang A. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otopathology in angiosarcoma of the temporal bone. Chen JX, Kozin ED, O'Malley J, et al. Laryngoscope. 2019;129:737–742. doi: 10.1002/lary.27281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adult Langerhans' cell histiocytosis with multisystem involvement: a case report. Kim SS, Hong SA, Shin HC, Hwang JA, Jou SS, Choi SY. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:0. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Low-grade papillary Schneiderian carcinoma of the sinonasal cavity and temporal bone. Brown CS, Abi Hachem R, Pendse A, Madden JF, Francis HW. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2018;127:974–977. doi: 10.1177/0003489418803391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Long-term outcomes of patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone after concomitant chemoradiotherapy. Shiga K, Katagiri K, Saitoh D, Ogawa T, Higashi K, Ariga H. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2018;79:0–21. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1651522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Primary middle ear mucosal melanoma: case report and comprehensive literature review of 21 cases of primary middle ear and Eustachian tube melanoma. Maxwell AK, Takeda H, Gubbels SP. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2018;127:856–863. doi: 10.1177/0003489418793154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diffuse giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath in temporomandibular joint: two case reports and review of the literature. Yan H, Wang F, Xiang L, Zhu W, Liang C. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:0. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the middle ear: a case report. Xu J, Yao M, Yang X, Liu T, Wang S, Ma D, Li X. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:0. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Temporal bone neoplasia: a rare entity. Breda MS, Menezes AS, Miranda DA, Rocha J. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:1–5. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-223590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Treatment and outcomes of carcinoma of the external and middle ear: the validity of en bloc resection for advanced tumor. Matoba T, Hanai N, Suzuki H, et al. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2018;58:32–38. doi: 10.2176/nmc.oa.2017-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cetuximab with radiotherapy as an alternative treatment for advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone. Ebisumoto K, Okami K, Hamada M, et al. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2018;45:637–639. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The first reported case of primary intestinal-type adenocarcinoma of the middle ear and review of the literature. Nader ME, Bell D, Ginsberg L, DeMonte F, Gunn GB, Gidley PW. Otol Neurotol. 2017;38:0–8. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone in 30 patients: difference in presentation and treatment in de novo disease vs radiation associated disease. Sun HY, Tsang RK. Clin Otolaryngol. 2017;42:1414–1418. doi: 10.1111/coa.12923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.A case of squamous cell carcinoma in the external auditory canal previously treated for verrucous carcinoma. Nam SJ, Yang CJ, Chung JW. J Audiol Otol. 2016;20:183–186. doi: 10.7874/jao.2016.20.3.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The first reported case of recurrent carcinoid tumor in the external auditory canal. McCrary HC, Faucett EA, Reghunathan S, Aly FZ, Khan R, Carmody RF, Jacob A. Otol Neurotol. 2017;38:114–117. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for auditory canal or middle ear cancer. Murai T, Kamata SE, Sato K, et al. Cancer Control. 2016;23:311–316. doi: 10.1177/107327481602300315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malignant transformation of a high-grade osteoblastoma of the petrous apex with subcutaneous metastasis. Kraft CT, Morrison RJ, Arts HA. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27304442/ Ear Nose Throat J. 2016;95:230–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Intraoperative radiation therapy as adjuvant treatment in locally advanced stage tumours involving the middle ear: a hypothesis-generating retrospective study. Cristalli G, Mercante G, Marucci L, Soriani A, Telera S, Spriano G. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2016;36:85–90. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.A toddler with rhabdomyosarcoma presenting as acute otitis media with mastoid abscess. Ng SY, Goh BS. Chin Med J (Engl) 2016;129:1249–1250. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.181973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Primary Ewing's sarcoma of the squamous part of temporal bone in a young girl treated with adjuvant volumetric arc therapy. Nandi M, Bhattacharya J, Goswami S, Goswami C. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11:1015–1017. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.168995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atypical cartilaginous tumor/chondrosarcoma, grade 1, of the mastoid in three family members: a new entity. Frisch CD, Inwards CY, Lalich IJ, Carter JM, Neff BA. Laryngoscope. 2016;126:0–3. doi: 10.1002/lary.25802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diagnosis and treatment of rare malignant tumors in external auditory canal (Article in Chinese) Wang F, Wu N, Hou Z, Liu J, Shen W, Han W, Yang S. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26665451/ Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2015;29:1438–1442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.A 43-year-old woman presenting with subacute, bilateral, sequential facial nerve palsies, then developing pseudotumour cerebri. O'Connor L, Croxson G, McCluskey P, Halmagyi GM. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:3–7. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-211399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Effectiveness of chemoradiotherapy for radiation-induced bilateral external auditory canal cancer: a case report and literature review. Maebayashi T, Ishibashi N, Aizawa T, et al. Head Neck. 2019;41:0–9. doi: 10.1002/hed.25728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Primary melanoma of the petrous temporal bone. McJunkin JL, Wiet RJ. Ear Nose Throat J. 2015;94:0–20. doi: 10.1177/014556131509400717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Unresectable recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone treated by induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemo-reirradiation: a case report and review of the literature. Kun M, Xinxin Z, Feifan Z, Lin M. Otol Neurotol. 2015;36:1543–1546. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Concomitant chemoradiotherapy for advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone. Shinomiya H, Hasegawa S, Yamashita D, et al. Head Neck. 2016;38:0–53. doi: 10.1002/hed.24133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Squamous cell carcinoma of the middle ear: report of three cases. Hu XD, Wu TT, Zhou SH. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25932267/ Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:2979–2984. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chronic discharging ear and multiple cranial nerve pareses: a sinister liaison. Dutta M, Mukherjee D, Mukhopadhyay S. Ear Nose Throat J. 2015;94:0–2. doi: 10.1177/014556131509404-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Efficacy of concurrent superselective intra-arterial chemotherapy and radiotherapy for late-stage squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone. Sugimoto H, Hatano M, Yoshida S, Sakumoto M, Kato H, Ito M, Yoshizaki T. Clin Otolaryngol. 2015;40:500–504. doi: 10.1111/coa.12431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Enhanced surface dose via fine brass mesh for a complex skin cancer of the head and neck: report of a technique. Daly ME, Chen AM, Mayadev JS, Stern RL. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2015;5:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Intracranial basal cell carcinoma with extensive invasion of the skull base. Mahvash M. Turk Neurosurg. 2014;24:571–573. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.8612-13.0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rare case study of a primary carcinoma of the petrous bone and a brief literature review. Atallah I, Karkas A, Righini CA, Lantuejoul S, Schmerber S. Head Neck. 2015;37:0–8. doi: 10.1002/hed.23819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rare case of temporal bone carcinoma with intracranial extension. Kasim KS, Abdullah AB. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;64:397–398. doi: 10.1007/s12070-011-0250-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cancer of the external auditory canal. Ouaz K, Robier A, Lescanne E, Bobillier C, Morinière S, Bakhos D. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2013;130:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma and petrous bone. Magliulo G, Iannella G, Alessi S, Veccia N, Ciniglio Appiani M. Otol Neurotol. 2013;34:0–2. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182814e58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mucoepidermoid carcinoma in the external auditory canal: a case report. Chung JH, Lee SH, Park CW, Tae K. Cancer Res Treat. 2012;44:275–278. doi: 10.4143/crt.2012.44.4.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trimodality approach for ceruminous mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the external auditory canal. Mourad WF, Hu KS, Shourbaji RA, Harrison LB. J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127:203–206. doi: 10.1017/S0022215112003015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the external auditory canal. Liu SC, Kang BH, Nieh S, Chang JL, Wang CH. J Chin Med Assoc. 2012;75:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uncommon lesions in the internal auditory canal (IAC): review of the literature and case report. Rohlfs AK, Burger R, Viebahn C, Held P, Woenckhaus M, Römer FW, Strutz J. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2012;73:160–166. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1304211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Malignant transformation from benign papillomatosis of the external auditory canal. Miah MS, Crawford M, White SJ, Hussain SS. Otol Neurotol. 2012;33:643–647. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31824b76d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Concomitant chemoradiotherapy as a standard treatment for squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone. Shiga K, Ogawa T, Maki A, Amano M, Kobayashi T. Skull Base. 2011;21:153–158. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1275244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bilateral inverted papilloma of the middle ear with intracranial involvement and malignant transformation: first reported case. Dingle I, Stachiw N, Bartlett A, Lambert P. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1615–1619. doi: 10.1002/lary.23247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mucosal melanoma of the middle ear cavity and Eustachian tube: a case report, literature review, and focus on surgical technique. Peters G, Arriaga MA, Nuss DW, Pou AM, DiLeo M, Scrantz K. Otol Neurotol. 2012;33:239–243. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182423191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Isolated recurrence of intracranial and temporal bone myeloid sarcoma--case report. Murakami M, Uno T, Nakaguchi H, et al. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2011;51:850–854. doi: 10.2176/nmc.51.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the external auditory canal. Magliulo G, Ciniglio Appiani M, Colicchio MG, Soldo P, Gioia CR. Otol Neurotol. 2012;33:0–2. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31821a8577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Endolymphatic sac papillary carcinoma treated with surgery and post-operative intensity-modulated radiotherapy: a rare case report. Gupta R, Vaidhyswaran AN, Murali V, Kameswaran M. J Cancer Res Ther. 2010;6:540–542. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.77062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ewing's sarcoma of the petrous temporal bone: case report and literature review. Kadar AA, Hearst MJ, Collins MH, Mangano FT, Samy RN. Skull Base. 2010;20:213–217. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1246224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Primary temporal inverted papilloma with premalignant change. Zhou H, Chen Z, Li H, Xing G. J Laryngol Otol. 2011;125:206–209. doi: 10.1017/S0022215110001829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 36-2010. A 50-year-old woman with pain and loss of hearing in the left ear. Stankovic KM, Juliano AF, Hasserjian RP. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2146–2156. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc1000967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Persistent otorrhoea with an abnormal tympanic membrane secondary to squamous cell carcinoma of the tympanic membrane. de Zoysa N, Stephens J, Mochloulis GM, Kothari PB. J Laryngol Otol. 2011;125:318–320. doi: 10.1017/S0022215110002203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.En bloc temporal bone resection using a diamond threadwire saw for malignant tumors. Jimbo H, Kamata S, Miura K, Masubuchi T, Ichikawa M, Ikeda Y, Haraoka J. J Neurosurg. 2011;114:1386–1389. doi: 10.3171/2010.8.JNS10294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.The problem of nodal disease in squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone. Zanoletti E, Danesi G. Acta Otolaryngol. 2010;130:913–916. doi: 10.3109/00016480903390152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Temporal bone carcinoma: a case report. Noorizan Y, Asma A. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23756808/ Med J Malaysia. 2010;65:162–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Temporal bone verrucous carcinoma: outcomes and treatment controversy. Miller ME, Martin N, Juillard GF, Bhuta S, Ishiyama A. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267:1927–1931. doi: 10.1007/s00405-010-1281-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ceruminous adenocarcinoma. Yang CY, Shu MT, Chen BF. Otol Neurotol. 2010;31:1011–1012. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181c996d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Temporal bone carcinoma with intracranial extension. Arora S, Sharma JK, Pippal S, Sethi Y, Yadav A. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;75:765. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30531-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prognostic factors for squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone: extensive bone involvement or extensive soft tissue involvement? Ito M, Hatano M, Yoshizaki T. Acta Otolaryngol. 2009;129:1313–1319. doi: 10.3109/00016480802642096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Synovial sarcoma involving the head: analysis of 36 cases with predilection to the parotid and temporal regions. Al-Daraji W, Lasota J, Foss R, Miettinen M. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1494–1503. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181aa913f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cholesteatoma triggering squamous cell carcinoma: case report and literature review of a rare tumor. Rothschild S, Ciernik IF, Hartmann M, Schuknecht B, Lütolf UM, Huber AM. Am J Otolaryngol. 2009;30:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.High grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the middle ear treated with extended temporal bone resection. Shailendra S, Elmuntser A, Philip R, Prepageran N. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19248700/ Med J Malaysia. 2008;63:247–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma on the external ear: a case report. Ragsdale BD, Lee JP, Mines J. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:267–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the external auditory canal. Carvalho CP, Barcellos AN, Teixeira DC, de Oliveira Sales J, da Silva Neto R. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;74:794–796. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)31394-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Squamous cell carcinoma of the external auditory canal. Lobo D, Llorente JL, Suárez C. Skull Base. 2008;18:167–172. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Angiosarcoma of the temporal bone. Hindersin S, Schubert O, Cohnen M, Felsberg J, Schipper J, Hoffmann TK. Laryngorhinootologie (Article in German) 2008;87:345–348. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.A case of petrous bone myxoid chondrosarcoma associated with cerebellar hemorrhage. Ohshige H, Kasai H, Imahori T, et al. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2005;22:41–44. doi: 10.1007/s10014-005-0175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the temporal bone. Viswanatha B. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17500393/ Ear Nose Throat J. 2007;86:220–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chondrosarcoma of the temporal bone. Yagisawa M, Ishitoya J, Tsukuda M, Sakagami M. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2007;34:527–531. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liposarcoma of temporal bone: a case report. Seo T, Nagareda T, Shimano K, Saka N, Kashiba K, Mori T, Sakagami M. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2007;34:511–513. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the external auditory canal (EAC) Bared A, Dave SP, Garcia M, Angeli SI. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:280–284. doi: 10.1080/00016480600818120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Verrucous carcinoma of the temporal bone and maxillary antrum: two unusual presentations of a rare tumor. Strojan P, Soba E, Gale N, Auersperg M. Onkologie. 2006;29:463–468. doi: 10.1159/000095379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Primary Ewing sarcoma of the petrous temporal bone: an exceptional cause of facial palsy and deafness in a nursling. Pfeiffer J, Boedeker CC, Ridder GJ. Head Neck. 2006;28:955–959. doi: 10.1002/hed.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rhabdomyosarcoma of the middle ear and mastoid: a case report and review of the literature. Abbas A, Awan S. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16408557/ Ear Nose Throat J. 2005;84:780–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Unilateral hearing loss as a presenting manifestation of granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma) Gokcan MK, Batikhan H, Calguner M, Tataragasi AI. Otol Neurotol. 2006;27:106–109. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000194813.69556.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Primary temporal bone angiosarcoma: a case report. Scholsem M, Raket D, Flandroy P, Sciot R, Deprez M. J Neurooncol. 2005;75:121–125. doi: 10.1007/s11060-005-0375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.A case of cervical metastases from temporal bone carcinoid. Pellini R, Ruggieri M, Pichi B, Covello R, Danesi G, Spriano G. Head Neck. 2005;27:644–647. doi: 10.1002/hed.20197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Carcinoid tumor of the middle ear: a case report. Chan KC, Wu CM, Huang SF. Am J Otolaryngol. 2005;26:57–59. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cystic brain necrosis and temporal bone osteoradionecrosis after radiotherapy and surgery in a patient of ear carcinoma. Wang PC, Tu TY, Liu KD. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15617312/ J Chin Med Assoc. 2004;67:487–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Angiosarcoma of the temporal bone (Article in Polish) Durko T, Papierz W, Pajor A. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14524190/ Otolaryngol Pol. 2003;57:427–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Primary intracranial Ewing's sarcoma of the mastoid bone. A case report (Article in Spanish) García-Pérez EA, Núñez-Ferrer P. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12599131/ Rev Neurol. 2003;36:340–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Granulocytic sarcoma of the temporal bone. Lee B, Fatterpekar GM, Kim W, Som PM. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12372738/ AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:1497–1499. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bilateral squamous cell carcinoma of the external auditory canals. Wolfe SG, Lai SY, Bigelow DC. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1003–1005. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200206000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cancer of the external auditory canal. Nyrop M, Grøntved A. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:834–837. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.7.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chondrosarcoma of the skull base. Neff B, Sataloff RT, Storey L, Hawkshaw M, Spiegel JR. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:134–139. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200201000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone: a radiographic-pathologic correlation. Gillespie MB, Francis HW, Chee N, Eisele DW. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11448354/ Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:803–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bilateral primary carcinoma of the external auditory meatus (Article in Japanese) Ohsako H, Haruta A, Tsuboi Y, Matsuura K, Komune S. Nihon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho. 2001;104:514–517. doi: 10.3950/jibiinkoka.104.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Primary papillary adenocarcinoma confined to the middle ear and mastoid. Dadaş B, Alkan S, Turgut S, Başak T. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;258:93–95. doi: 10.1007/s004050000288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Radiology forum: quiz case. Diagnosis: rhabdomyosarcoma with perineural intracranial invasion. Lehman DA, Mancuso AA, Antonelli PJ. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:331–332. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone: diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Chee G, Mok P, Sim R. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11193117/ Singapore Med J. 2000;41:441–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Malignancy of the temporal bone and external auditory canal. Lim LH, Goh YH, Chan YM, Chong VF, Low WK. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:882–886. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59980070018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Carcinoma of the ear: a case report of a possible association with chlorinated disinfectants. Monem SA, Moffat DA, Frampton MC. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:1004–1007. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100145839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the middle ear-a case report. Soh KB, Tan HK, Sinniah R. J Laryngol Otol. 1996;110:249–251. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100133328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.A case of carcinoma of middle ear treated with cytotoxic perfusion. Mahindrakar NH. J Laryngol Otol. 1965;79:921–925. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100064586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.A case of bilateral middle-ear squamous cell carcinoma. Takano A, Takasaki K, Kumagami H, Higami Y, Kobayashi T. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115:815–818. doi: 10.1258/0022215011909035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Malignant melanoma of the middle ear, a rare site (Article in Spanish) Urpegui García A, Lahoz Zamarro T, Muniesa Soriano JA, et al. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10619884/ Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 1999;50:559–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rapidly invading sebaceous carcinoma of the external auditory canal. Ray J, Worley GA, Schofield JB, Shotton JC, al-Ayoubi A. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:578–580. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100144536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Temporal bone tumours in patients irradiated for nasopharyngeal neoplasm. Goh YH, Chong VF, Low WK. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:222–228. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100143622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chondrosarcoma of the temporal bone and otosclerosis. Ramírez-Camacho R, Pinilla M, Ramón y Cajal S, García Berrocal JR, Vicente J. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1998;60:58–60. doi: 10.1159/000027565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Malignant melanoma of the external auditory canal. Milbrath MM, Campbell BH, Madiedo G, Janjan NA. Am J Clin Oncol. 1998;21:28–30. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199802000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.En bloc resection of the temporal bone for middle ear carcinoma extending to the cranial base (Article in Japanese) Somekawa Y, Asano K, Hata M. Nihon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho. 1997;100:782–789. doi: 10.3950/jibiinkoka.100.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Spindle cell variant of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Don DM, Newman AN, Fu YS. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;116:529–532. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the temporal bone with endocranial extension. Nakayama K, Nemoto Y, Inoue Y, et al. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9111672/ AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:331–334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Primary Ewing's sarcoma of the temporal bone with intracranial, extracranial and intraorbital extension. Case report. Kuzeyli K, Aktürk F, Reis A, et al. Neurosurg Rev. 1997;20:132–134. doi: 10.1007/BF01138198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Temporal bone hemangiopericytoma. Cross DL, Mixon C. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;114:631. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989670258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chondrosarcoma arising in the mastoid involving the intratemporal facial nerve. Zhao EE, Liu YF, Oyer SL, Smith MT, McRackan TR. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145:392–393. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.A case of middle ear carcinoma with high plasma G-CSF level (Article in Japanese) Kurihara H, Tanaka K, Yoshitsuru H, Nishio M, Aikawa K, Yamashiro K. Nihon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho. 1993;96:415–420. doi: 10.3950/jibiinkoka.96.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Malignant melanoma of the temporal bone (Article in German) Walther EK, Krick T. Laryngorhinootologie. 1993;72:48–50. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-997853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Carcinoma of temporal bone presenting as malignant otitis externa. al-Shihabi BA. J Laryngol Otol. 1992;106:908–910. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100121255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Primary Ewing's sarcoma of the temporal bone. Watanabe H, Tsubokawa T, Katayama Y, Koyama S, Nakamura S. Surg Neurol. 1992;37:54–58. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(92)90067-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rhabdomyosarcoma of the ear and temporal bone. Wiatrak BJ, Pensak ML. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:1188–1192. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198911000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Squamous cell carcinoma of the external auditory meatus (canal) Arriaga M, Hirsch BE, Kamerer DB, Myers EN. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;101:330–337. doi: 10.1177/019459988910100306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Radiation-induced sarcoma of the skull: a case report. Garner FT, Barrs DM, Lanier DM, Carter TE, Mischke RE. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;99:326–329. doi: 10.1177/019459988809900311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the temporal bone with multiple metastases. Case report (Article in Japanese) Takeda S, Sakaki S, Fukui K, Sadamoto K, Tabei R. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1987;27:779–783. doi: 10.2176/nmc.27.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Primary adenocarcinoma of the temporal bone mimicking paragangliomas: radiographic and clinical recognition. Goebel JA, Smith PG, Kemink JL, Graham MD. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;96:231–238. doi: 10.1177/019459988709600302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Total temporal bone resection for squamous cell carcinoma. Sataloff RT, Myers DL, Lowry LD, Spiegel JR. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;96:4–14. doi: 10.1177/019459988709600102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chondrosarcoma of the temporal bone. Diagnosis and treatment of 13 cases and review of the literature. Coltrera MD, Googe PB, Harrist TJ, Hyams VJ, Schiller AL, Goodman ML. Cancer. 1986;58:2689–2696. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19861215)58:12<2689::aid-cncr2820581224>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Primary adenocarcinoma of the temporal bone with posterior fossa extension: case report. Gulya AJ, Glasscock ME, Pensak ML. Laryngoscope. 1986;96:675–677. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198606000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Malignant degeneration of an epidermoid of the temporal bone. Kveton JF, Glasscock ME 3rd, Christiansen SG. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;94:633–636. doi: 10.1177/019459988609400518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chondrosarcoma of the skull base. Kveton JF, Brackmann DE, Glasscock ME 3rd, House WF, Hitselberger WE. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;94:23–32. doi: 10.1177/019459988609400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Primary chondroid chordoma arising from the base of the temporal bone. A 10-year post-operative follow-up. Hasegawa M, Nishijima W, Watanabe I, Nasu M, Kamiyama R. J Laryngol Otol. 1985;99:485–489. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100097097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Verrucous carcinoma of the ear. Case report. Proops DW, Hawke WM, van Nostrand AW, Harwood AR, Lunan M. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1984;93:385–388. doi: 10.1177/000348948409300420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Total en bloc resection of the temporal bone and carotid artery for malignant tumors of the ear and temporal bone. Graham MD, Sataloff RT, Kemink JL, Wolf GT, McGillicuddy JE. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:528–533. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198404000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Primary adenomatous neoplasm of the middle ear. Eden AR, Pincus RL, Parisier SC, Som PM. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:63–67. doi: 10.1002/lary.5540940115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Osteogenic sarcoma of the temporal bone. Gertner R, Podoshin L, Fradis M. J Laryngol Otol. 1983;97:627–631. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100094718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Tumors arising from the glandular structures of the external auditory canal. Hicks GW. Laryngoscope. 1983;93:326–340. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198303000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the middle ear and temporal bone. Cannon CR, McLean WC. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1983;91:96–99. doi: 10.1177/019459988309100120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 40-1983. Preauricular mass five years after treatment of a brain tumor. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:843–850. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198310063091408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Treatment of tumours in the petrous part of the temporal bone. Kynaston B. Australas Radiol. 1980;24:246–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.1980.tb02193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Squamous cell carcinoma of the middle ear. Michaels L, Wells M. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1980;5:235–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1980.tb01653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Primary carcinoma involving the temporal bone: analysis of twenty-five cases. Wagenfeld DJ, Keane T, van Nostrand AW, Bryce DP. Laryngoscope. 1980;90:912–919. doi: 10.1002/lary.1980.90.6.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Basal cell carcinoma of the temporal bone. Parkin JL, Stevens MH. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (1979) 1979;87:645–647. doi: 10.1177/019459987908700519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Radiation-induced carcinoma of the temporal bone. Applebaum EL. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (1979) 1979;87:604–609. doi: 10.1177/019459987908700512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Radium-induced malignant tumors of the mastoid and paranasal sinuses. Littman MS, Kirsh IE, Keane AT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1978;131:773–785. doi: 10.2214/ajr.131.5.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Ceruminous gland adenocarcinoma: a light and electron microscopic study. Michel RG, Woodard BH, Shelburne JD, Bossen EH. Cancer. 1978;41:545–553. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197802)41:2<545::aid-cncr2820410222>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Treatment of carcinoma of the middle ear. Sinha PP, Aziz HI. Radiology. 1978;126:485–487. doi: 10.1148/126.2.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Management of malignancy of the temporal bone. Gacek RR, Goodman M. Laryngoscope. 1977;87:1622–1634. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197710000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Radiation induced carcinoma of the temporal bone. Ruben RJ, Thaler SU, Holzer N. Laryngoscope. 1977;87:1613–1621. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197710000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Rhabdomyosarcoma of the middle ear and mastoid. Pahor AL. J Laryngol Otol. 1976;90:585–591. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100082487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Cancer of the middle ear and mastoid process. Hinton CD. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4819889/ J Natl Med Assoc. 1974;66:125–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Partial temporal bone resection for basal cell carcinoma of the external auditory canal with preservation of facial nerve and hearing. Goldman NC, Hardcastle B. Laryngoscope. 1974;84:84–89. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197401000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Rhabdomyosarcoma--a temporal bone report. Gothamy B, Fujita S, Hayden RC Jr. Arch Otolaryngol. 1973;98:106–111. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1973.00780020112009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Embryonal rhabdo-myosarcoma of middle ear: report of a case with 12 years' survival with a review of the literature. Barnes PH, Maxwell MJ. J Laryngol Otol. 1972;86:1145–1154. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100076337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Radical surgery for carcinoma of the middle ear. McCrea RS. Laryngoscope. 1972;82:1514–1523. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197208000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Chondrosarcoma with subarachnoid dissemination. Leedham PW, Swash M. J Pathol. 1972;107:59–61. doi: 10.1002/path.1711070111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Cancer of the middle ear. Fairman HD. http://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5083311/ Proc R Soc Med. 1972;65:247–248. doi: 10.1177/003591577206500309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Rhabdomyosarcoma of the middle-ear region; report of a case. Holman RL. J Laryngol Otol. 1956;70:415–419. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100053111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Cancer of the external auditory canal: treatment with radical mastoidectomy and irradiation. Tabb HG, Komet H, Mclaurin JW. Laryngoscope. 1964;74:634–643. doi: 10.1288/00005537-196405000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Neoplasms of the middle ear and mastoid: report of fifty-four cases. Bradley WH, Maxwell JH. Laryngoscope. 1954;64:533–556. doi: 10.1288/00005537-195407000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Primary carcinoma of external auditory canal, middle ear and mastoid. Liebeskind MM. Laryngoscope. 1951;61:1173–1187. doi: 10.1288/00005537-195112000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Total resection of temporal bone for malignancy of the middle ear. Campbell E, Volk BM, Burklund CW. Ann Surg. 1951;134:397–404. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195113430-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Rhabdomyosarcoma of the middle ear and mastoid. Jaffe BF, Fox JE, Batsakis JG. Cancer. 1971;27:29–37. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197101)27:1<29::aid-cncr2820270106>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Cancer of the external auditory canal with extensive osteoradionecrosis of the skull base after re-irradiation with particle beams: a case report. Matsuo M, Yasumatsu R, Yoshida S. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14:1097–1102. doi: 10.1159/000516801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Temporal bone carcinoma: treatment patterns and survival. Seligman KL, Sun DQ, Ten Eyck PP, Schularick NM, Hansen MR. Laryngoscope. 2020;130:0–20. doi: 10.1002/lary.27877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Primary liposarcoma with cholesteatoma in mastoid. Sato MP, Saito K, Fujita T, Seo T, Doi K. J Int Adv Otol. 2020;16:134–137. doi: 10.5152/iao.2019.6709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.A case of external auditory canal sebaceous carcinoma: literature review and treatment discussion. Saadi R, Pennock M, Baker A, Isildak H. Biomed Hub. 2020;5:72–78. doi: 10.1159/000508058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Left chronic otitis media with squamous cell carcinoma of the middle ear and postauricular mastoid fistula: a case report. Acharya SP, Pathak C, Giri S, Bista M, Mandal D. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2020;58:341–344. doi: 10.31729/jnma.4954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Melanoma of the external auditory canal: a review of seven cases at a tertiary care referral center. Appelbaum EN, Gross ND, Diab A, Bishop AJ, Nader ME, Gidley PW. Laryngoscope. 2021;131:165–172. doi: 10.1002/lary.28548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Variations of en bloc resection for advanced external auditory canal squamous cell carcinoma: detailed anatomical considerations. Komune N, Kuga D, Miki K, Nakagawa T. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:4556. doi: 10.3390/cancers13184556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Invasion patterns of external auditory canal squamous cell carcinoma: a histopathology study. Ungar OJ, Santos F, Nadol JB, Horowitz G, Fliss DM, Faquin WC, Handzel O. Laryngoscope. 2021;131:0–7. doi: 10.1002/lary.28676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Surgical treatment for squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone: predictors of survival. Smit CF, Boer N, Lissenberg-Witte BI, Merkus P, Hensen EF, Leemans CR. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2021;41:308–316. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-N1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Temporal bone squamous cell carcinoma: a change in treatment. Ngu CY, Mohd Saad MS, Tang IP. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34508382/ Med J Malaysia. 2021;76:725–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.En bloc subtotal temporal bone resection in a case of advanced ear cancer: 2-dimensional operative video. Kimura H, Taniguchi M, Shinomiya H, et al. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2020;19:0–3. doi: 10.1093/ons/opaa124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Staging proposal for external auditory meatus carcinoma based on preoperative clinical examination and computed tomography findings. Arriaga M, Curtin H, Takahashi H, Hirsch BE, Kamerer DB. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1990;99:714–721. doi: 10.1177/000348949009900909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Squamous cell carcinoma of the external auditory canal: an evaluation of a staging system. Moody SA, Hirsch BE, Myers EN. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10912706/ Am J Otol. 2000;21:582–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.The role of facial palsy in staging squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone and external auditory canal: a comparative survival analysis. Higgins TS, Antonio SA. Otol Neurotol. 2010;31:1473–1479. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181f7ab85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Squamous cell cancer of the temporal bone: a review of the literature. Lechner M, Sutton L, Murkin C, et al. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278:2225–2228. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06281-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Multicenter experiences in temporal bone cancer surgery based on 89 cases. Wierzbicka M, Niemczyk K, Bruzgielewicz A, et al. PLoS One. 2017;12:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Prognostic factors affecting surgical outcomes in squamous cell carcinoma of external auditory canal. Nam GS, Moon IS, Kim JH, Kim SH, Choi JY, Son EJ. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;11:259–266. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2017.01340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Trends of temporal bone cancer: SEER database. Acharya PP, Sarma D, McKinnon B. Am J Otolaryngol. 2020;41:102297. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2019.102297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Middle ear cancer: a population-based study. Gurgel RK, Karnell LH, Hansen MR. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:1913–1917. doi: 10.1002/lary.20202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Twenty-year experience with salvage total laryngectomy: lessons learned. Tsetsos N, Poutoglidis A, Vlachtsis K, Stavrakas M, Nikolaou A, Fyrmpas G. J Laryngol Otol. 2021;135:729–736. doi: 10.1017/S0022215121001687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]