Abstract

Objective:

The study objective was to explore the preliminary efficacy of trauma-sensitive yoga compared to cognitive processing therapy (CPT) for women Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) related to military sexual trauma (MST) in a pilot randomized control trial (RCT). We then compared these results to published interim results for the subsequent full-scale RCT.

Method:

The analytic sample included women Veterans (N = 41) with PTSD related to MST accessing healthcare in a southeastern Veterans Affairs Health Care System. The majority were African American, non-Hispanic (80.5 %). The protocol-driven group interventions, Trauma Center Trauma-Sensitive Yoga (TCTSY; n = 17) and the evidence-based control condition, CPT (n = 24), were delivered weekly for 10 and 12 sessions, respectively. Multilevel linear models (MLM) were used to compare changes over time between the two groups.

Results:

The primary outcomes presented here are PTSD symptom severity and diagnosis, assessed using the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) and the PTSD Symptom Checklist (PCL) total scores. PTSD symptom severity on both clinician-administered (CAPS) and self-reported (PCL) measures, improved significantly (p < .005) over time, with large within group effect sizes (0.90–0.99) consistent with the subsequent RCT. Participants in the TCTSY group showed clinically meaningful improvements earlier than the CPT group participants from baseline on the CAPS and PCL Total scores.

Conclusions:

Results support published findings of the effectiveness of TCTSY in the treatment for PTSD related to MST among women Veterans, particularly African American women. TCTSY warrants consideration as an adjunctive, precursor, or concurrent treatment to evidence-based psychotherapies. Future research should include patient preference, men with sexual trauma, and civilian populations.

Keywords: Posttraumatic stress disorder, Veterans, Women, yoga, African American, Military sexual trauma, Trauma-sensitive yoga

1. Introduction

Women represent nearly 10 % of the U.S. Veteran population,1 a number that is projected to increase, while the total Veteran population is projected to steadily decrease.2 Women Veterans who utilize VA services report a higher prevalence of military sexual trauma (MST; 15–29 %) compared to their male counterparts (4 %; 3–5). When considering military personnel and Veterans, 13.9 % have reported MST with mean rates of 38.4 % for women and 3.9 % for men when measures include harassment and assault.6 MST is the primary cause of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among women Veterans.6,7 PTSD and MST contribute to significant physical and mental health problems, disability, sexual dysfunction, and poor quality of life.8–10

Current evidence-based psychotherapies (EBPs) for PTSD (e.g., prolonged exposure therapy; PE, cognitive processing therapy; CPT) have limitations showing not all individuals benefit from them.11,12 Dropout among those who receive EBPs for PTSD range from 30% to 40%; a recent meta-analysis reported an average of 18 % attrition.13–15,11,12,16 In a review of psychotherapy randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for military-related PTSD, authors reported clinically significant pre/post change, however 60–70 % of Veterans continued to meet the criteria for PTSD post-treatment.12

Veterans have expressed desire for non-pharmacological, non-psychotherapeutic treatments for PTSD, such as complementary and integrative health (CIH) approaches.17 The use of CIH modalities to improve overall health and well-being and to treat various physical and psychological conditions is a strategic priority in the Veterans Administration (VA).18 In 2017, the VA issued a directive that its facilities provide CIH services, including yoga.19,20 Empirical support of yoga to treat PTSD among Veterans is promising but has been limited by varying study designs, heterogeneity of the intervention, and small sample sizes.21–24 At the time this study was conducted, there were very few studies to support the feasibility or effectiveness of yoga studies among US Veterans, primarily due to insufficiently powered studies.25,26,8,27 Several studies have been published since then which add strong support to the feasibility of yoga clinical trials within the VA and the acceptability of yoga as a clinical intervention for Veterans.21,23,24 Interim results from the full scale RCT that followed the pilot study presented here demonstrated the effectiveness of Trauma Center Trauma-Sensitive Yoga (TCTSY) for PTSD in the same study population, with comparable results to CPT and with higher treatment completion.28

Three shortcomings of the evidence base are that studies of yoga for PTSD: 1) generally have not distinguished among trauma types causing PTSD; 2) have not paired yoga approaches with nuances in the presentation and etiological factors of PTSD; and 3) samples have been predominantly white and male. For example, studies of yoga for PTSD with Veterans typically include a majority of men, focus on combat-related trauma or do not specify the precipitating trauma type (e.g. combat, MST, or civilian trauma of varying types.21–23 The effectiveness of yoga for PTSD related to sexual trauma is under-studied; there is a lack of clarity on its mechanisms of action. All yoga is not the same, and yoga for sexual trauma-related PTSD requires a theoretically-sound, trauma-sensitive design that addresses the embodiment challenges that sexual trauma survivors often experience.29–32 While a variety of yoga interventions have been investigated as potential PTSD treatments in civilian, military, and Veteran populationsTCTSY is the only yoga intervention specifically designed for survivors of sexual trauma.26,22,30,33,31 TCTSY is based on the recognition that trauma, particularly sexual trauma, is fundamentally an embodied experience, meaning that sexual trauma is experienced by the body first and primarily.31 As such, an embodied approach to treatment provides a direct trajectory to healing, rather than the indirect pathway of addressing the thoughts and feelings that follow the traumatic experience.34 The focus of TCTSY is, interoception (i.e. the perceptions of sensations in the body), reflecting the body’s physiological state. As such, TCTSY is explicitly not about cognition and emotion, thus it potentially provides an alternative pathway to healing than that offered by cognitively-based psychotherapies.

In this paper, we present preliminary efficacy results of TCTSY compared to CPT on PTSD symptom severity from a pilot study conducted in 2013–2015. We then compare these results with interim results from the subsequent RCT that had the same study design as the pilot study.28 The purpose of the pilot study was to evaluate the feasibility of conducting an RCT of TCTSY as a clinical intervention for women Veterans with PTSD who had experienced MST and endorsed chronic pain, and to evaluate biomarkers and psychophysiological markers as outcome measures for future studies of trauma-sensitive yoga with this population. The feasibility findings are presented elsewhere.35 Specific procedural changes from the pilot study to the full RCT were baseline data collection prior to randomization (correction of a procedural error) and inclusion of an intervention cross-over option following completion of the intervention to which participants were randomized. The cross-over option was intended to increase enrollment and retention for those not randomized to their preferred treatment condition.

The reported interim findings from the RCT were obtained from the same study site with the same population as those in this pilot study. Two analytic changes we have made since publication of the interim findings are: 1) a change in the definition of CPT treatment completion to 8 or more of 12 sessions rather than 9, based on reviewer feedback and literature and; 2) administrative removal of one participant from the database due to an enrollment error. Thus, in our Results and Discussion below, the interim results will differ slightly from the published results in terms of sample size (now n = 103), effect sizes, and treatment completion numbers.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

The results presented here are an analysis of PTSD symptom severity and PTSD diagnosis outcomes obtained in a feasibility study of TCTSY compared to CPT for PTSD in women Veterans who experienced MST.35 The study was conducted in 2013–2015 and was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board and relevant VA research oversight committees. After providing informed consent, participants were assessed for demographics, lifetime trauma history, and co-occurring mental health disorders. Outcomes were assessed using self-report and clinician-interviews at four time points: baseline (T1), mid-intervention (T2), 2-weeks post-intervention (T3), and 3-months post-intervention (T4). Participants received compensation for data collection ($60 per assessment) and treatment session attendance ($15 per TCTSY or CPT session).

2.2. Participants

Recruitment was conducted at a southeastern VA in PTSD clinics and via posted flyers in targeted locations within the VA. Women Veterans were included who were diagnosed with PTSD or met criteria for PTSD upon clinical assessment by the research team and who identified MST as the index trauma. Participants were included who endorsed suicidal ideation without current, active suicidal intent or plan. Exclusion criteria included significant cognitive impairment, current moderate to severe substance abuse or dependence, and uncontrolled medical conditions that could cause overlapping psychiatric symptoms, (e.g. hyperthyroidism and liver failure). Following a brief phone screening to determine initial eligibility, potential participants were offered enrollment in the study and subsequently underwent evaluation to assess suitability for study inclusion.

2.3. Interventions

We used available manualized protocols for TCTSY and CPT in use at the time of the study. Detailed protocol descriptions, details on facilitation, and efforts for maintaining fidelity for both the experimental and control interventions are described elsewhere.35

The TCTSY intervention protocol was developed by David Emerson and Jennifer Turner at the Justice Resource Institute.33 The TCTSY intervention is Hatha yoga in style with modifications made to accomodate differing levels of physical ability and agility.23 For example, using a chair for balance during standing forms or sitting rather than lowering oneself to the ground for recumbant forms. The protocol was developed to treat women with complex PTSD related to childhood sexual abuse who were unresponsive to standard PTSD treatment for three years or more. The TCTSY protocol consisted of ten weekly 60-min group sessions; sessions were centered around the key principles of TCTSY: experiencing the present moment, making choices, taking effective action, and creating rhythms.33 A qualitative descriptive analysis of this yoga modality reflected similar themes: gratitude, compassion, relatedness, acceptance, centeredness, and empowerment.34 The sessions were co-facilitated by two yoga teachers who became TCTSY certified facilitators during the course of the study. The presence of two facilitators enabled one to facilitate the session while the other demonstrated modifications per the needs of the individuals in the sessions.

CPT, a cognitively-based psychotherapy, is a first-line PTSD treatment in the VA.36 The CPT manualized intervention was delivered in twelve weekly 90-minute group sessions.37 The theoretical rationale of cognitively-based, empirically supported psychotherapies for PTSD, such as CPT, identifies that trauma, including sexual trauma, leads to cognitive distortions about oneself, others, and the world, (e.g., “Something is wrong with me”, “People can’t be trusted”, “The world is unsafe”). These post-traumatic distorted cognitions contribute to the development of other PTSD symptoms (e.g., avoidance behaviors, emotional dysregulation, and hypervigilance). 38 The CPT group sessions focused on identifying trauma-related thoughts and teaching participants to challenge these thoughts and replace them with more accurate, cognitively-flexible thoughts about themselves, others, and the world. Our feasibility manuscript includes details on the structure and format of the experimental and control conditions as well as fidelity outcomes.35 In short, feasibility was demonstrated relative to study recruitment, delivery of both interventions with fidelity, and data collection.

2.4. Outcomes

At the time this study was conducted (2013–2015), the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revised (DSM-IV-TR) was in effect and outcome measures were based on DSM-IV-TR criteria.39 The full RCT was conducted from 2015 to 2022; PTSD outcomes were based on DSM-5 criteria.40 Thus, we will use effect sizes to compare the PTSD outcomes in the pilot versus the RCT rather than raw scores, since they are not equivalent.

2.4.1. Clinician Administered PTSD Scale(CAPS)

The CAPS is an interviewer-administered diagnostic instrument that assesses lifetime and current PTSD diagnosis, symptoms, and global PTSD symptom severity.41 The CAPS yields a total score indicating the severity of overall PTSD, and subscale scores of the three symptom clusters of PTSD (re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal) as diagnosed by the DSM-IV-TR.39 It assesses the validity of the participant’s responses and has shown excellent validity and reliability among Veteran samples (Cronbach’s alpha’s range .80–0.90;41 α = 0.867 in this sample). CAPS administration was conducted by research team members trained to use this instrument for research purposes. Interrater reliability was maintained by Co-Investigator review and scoring of CAPS recordings; discrepancies were resolved via discussion with assessors.

2.4.2. PTSD Checklist (PCL)

The PCL (17-item; 5-point Likert-scale) is a self-report measure used to assess PTSD symptoms over an episode of care (Cronbach’s α = 0.94 from previous research;42 α = 0.905 in this sample). The items of the PCL parallel DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria. It yields a total score for PTSD severity and subscale scores for re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal symptom clusters, consistent with DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria.39

2.5. Sample size

In the pilot study, we aimed to use the data to inform the necessary sample size for a sufficiently powered large RCT. Thus, a power analysis was performed based on an estimated starting sample size of 40 (20 per group). It was anticipated that up to 50 % attrition could occur yielding a final minimum sample size of 20 (10 per group). Given two groups and four time points, with final samples sizes of 10 per group, we were powered at 80 % power and 5 % level of significance to detect large effect sizes for group (Cohen’s f = 0.66), time (f = 0.76) and group-by-time (f = 0.76) effects. Power analysis was performed using PASS v.15 power analysis software. Each of the two cohorts had participants randomized to TCTSY (Cohort 1, n = 9; Cohort 2, n = 8; total=17) or CPT (Cohort 1, n = 11; Cohort 2 n = 14; total = 25). One CPT participant withdrew prior to baseline assessment, yielding a final sample size of N = 41.

2.6. Randomization

A randomization schedule was generated by the block randomization algorithm “random sorting using maximum allowable percent deviation” using the PASS v.15 power analysis software package.43 Once participants were consented, a staff member informed them of their randomization assignment. Following randomization, each participant completed a detailed assessment to confirm eligibility and obtain baseline data on outcome measures.

2.7. Statistical methods

Data were entered into Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a secure, web-based application for building and managing online surveys and databases.44 Data were continually checked for accuracy and completeness. Descriptive statistics were computed for all measures at each time point. The distribution of all measures was reviewed for normality and missing data due to attrition were assessed using t-tests to compare baseline scores for those who returned for one or more follow-up time points versus those who only completed baseline assessments. None of the demographics or other measures were significantly associated with attrition, so no further covariate adjustments were considered in the final models. Multilevel linear models (MLM) were used to compare changes over time between the two groups, with follow-up post hoc tests performed using Sidak pairwise error rate adjustment.45 For outcomes where there were significant group differences at baseline, the baseline scores were subtracted and the MLM models re-run using the change scores from baseline for these measures (PCL and CAPS total scores). Significance results (p-values) for statistical tests and models are reported; we also report 95 % confidence intervals and clinically meaningful differences to improve interpretability of the findings.46 We used a change in 10 or more points on the CAPS and PCL to determine clinically meaning differences.47,48 All computations were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0.49

3. Results

We assessed 250 women for eligibility; 208 were ineligible for reasons listed in our CONSORT chart (Appendix 1). Forty-two women were consented and enrolled in the study, one subsequently withdrew prior to baseline data collection, yielding an intent to treat sample of 41 women with baseline data, ranging in age from 30 to 72 (M = 45, SD = 9.9). The majority (80.5 %) self-identified as African American, non-Hispanic. Demographic data for the sample are presented in Table 1. Intervention groups did not differ significantly on age, race/ethnicity, marital status, past psychiatric hospitalizations, or pain (Pain Outcomes Questionnaire; and PROMIS Pain) at baseline. The CPT group had slightly less education. The CPT group had higher depression symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory-2nd Edition/BDI-II) and clinician assessed PTSD severity (CAPS Total score) at baseline. For outcome analyses, the sample sizes at mid-intervention, 2-weeks post-intervention and 3-months post-intervention were 23, 23, and 21, respectively. Although the randomization schedule had equal allocation for TCTSY and CPT (cohorts of 10 for both interventions), recruitment challenges caused delays and intervention cohorts were begun with lower than projected enrollment. This resulted in unequal distribution across intervention groups (TCTSY = 17; CPT = 25) as well as unequal education levels.

Table 1.

Sample demographics.

| All (n = 41) |

TCTSY (n = 17) |

CPT (n = 24) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n | Mda | SDa | n | Ma | SD | n | M | SD |

| Age [range 30–72 yrs.] | 41 | 45.0 | 9.9 | 17 | 46.1 | 12.4 | 24 | 44.2 | 7.9 |

| BDI-IIa [range 14–55] | 40 | 31.5 | 10.2 | 17 | 26.9 | 9.0 | 23 | 34.9 | 9.8 |

| POQb [range 3–10] | 40 | 6.6 | 1.8 | 17 | 6.2 | 1.8 | 23 | 6.9 | 1.8 |

| PROMISc Pain [range 40.7–77] | 40 | 63.6 | 8.0 | 17 | 61.3 | 9.2 | 23 | 65.3 | 6.7 |

| n | Md | IQR a | n | Md | IQR | n | Md | IQR | |

| Education [range 12–20 yrs.] | 40 | 15 | [14,16] | 16 | 16 | [14.5, 16.8] | 24 | 14 | [13,16] |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||

| African American | 33 | 80.5 % | 14 | 82.4 % | 19 | 79.2 % | |||

| White; Non-Hispanic | 5 | 12.2% | 2 | 11.8% | 3 | 12.5 % | |||

| Other/Mixed | 3 | 7.3 % | 1 | 5.9 % | 2 | 8.3 % | |||

| Marital Status | |||||||||

| Single, never married | 7 | 17.1 % | 3 | 17.6% | 4 | 16.7 % | |||

| Married/Partnered | 17 | 41.5 % | 8 | 47.1 % | 9 | 37.5 % | |||

| Divorced/Separated | 15 | 36.6 % | 5 | 29.4 % | 10 | 41.7 % | |||

| Widowed | 2 | 4.9 % | 1 | 5.9 % | 1 | 4.2 % | |||

| Past Psychiatric Hospitalization | 10 | 24.4 % | 4 | 23.5 % | 6 | 25.0 % | |||

BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd Edition.

POQ Pain Outcomes Questionnaire.

PROMIS – Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

Attrition from randomization to the first intervention session was 29 % for the CPT group and 17.6 % for the TCTSY group. This difference was not statistically significant (Fisher’s Exact Test p = .480) due to the small sample size. The median number of sessions attended by participants was 8.5/10 for TCTSY and 5/12 for CPT. Participants were considered to have completed treatment if they attended 67–70 % or more of their scheduled sessions (7 or more of 10 for TCTSY, 8 or more of 12 for CPT). Completion thresholds for both interventions were based on similar studies.33,50,51,37,52 Treatment completion was higher in the TCTSY group (58.8 %) than in the CPT group (41.7 %). Again, this finding lacked statistical significance (χ2(1) = 1.172, p = .279). Study retention and treatment completion are described in detail with feasibility findings.35

3.1. Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS)

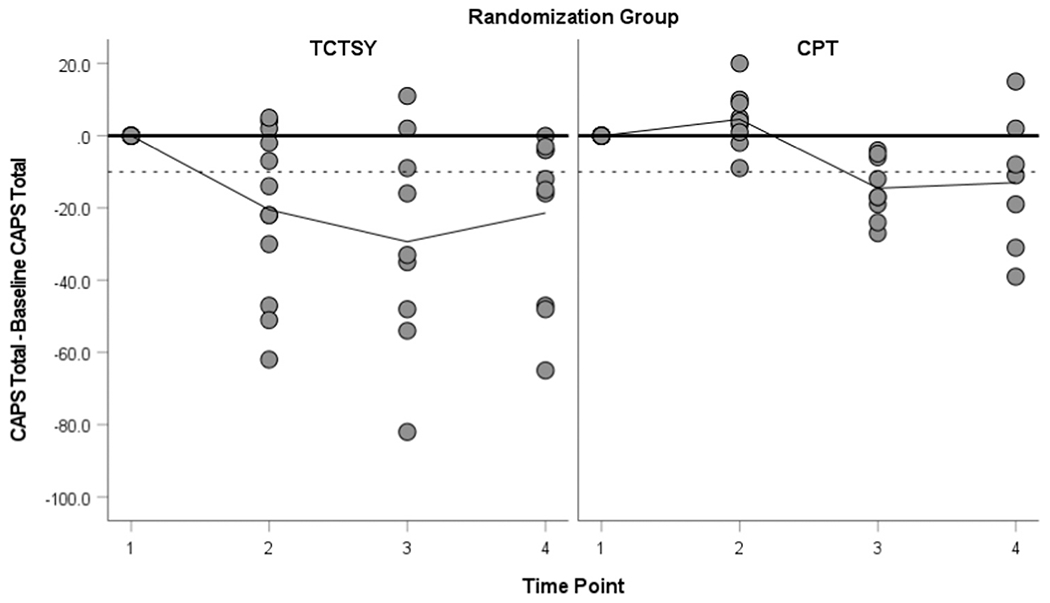

CAPS total scores demonstrated statistically significant time effects (p < .05) and group effects. Since there was a significant difference between the two groups at baseline (TCTSY = 67.7; CPT = 79.4; t(37) = 2.151, p = .038), the baseline scores were added as a covariate to the MLM model (which was significant: F(1, 39.906) = 40.034, p < .001). After adjusting for baseline scores as a covariate, there was a statistically significant group-by-time interaction effect (p = .021), indicating different longitudinal changes for the two groups on their CAPS total scores. The primary difference between the two groups is that the TCTSY group showed a larger improvement from baseline to mid-intervention than the CPT group. The CPT group did not show significant improvements until 2-weeks post-intervention. As presented in Table 2, both groups improved across time. The TCTSY group had noticeably more participants who met or exceeded a ≥ 10 point improvement in their CAPS total scores, with 58.3 % (versus 0 % for CPT) achieving clinically meaningful improvement by mid-intervention, 66.7 % (same for CPT) by 2-weeks post intervention and 60 % (versus 57.1 % for CPT) by 3-months post intervention. Fig. 1 shows the range of improvements on CAPS total scores from baseline for both groups over time. The dashed line indicates a decrease of ≥ 10 points from baseline. Fig. 1 shows noticeably more TCTSY participants with clinically meaning improvements for their CAPS total scores with several TCTSY subjects showing even greater decreases in CAPS total scores compared to CPT subjects.

Table 2.

CAPS total scores (Time by Group).

| Multilevel Linear Model Effects: | Δ Between Groupsa |

95 % CI |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | SD | G; T; GxT | M | SE | P | LB | UB | |||

| CAPS Total Score | CPT | T1 | 22 | 79.4 | 15.3 | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| T2 | 10 | 79.6 | 15.5 | 25.1 | 7.1 | .003 | 9.8 | 40.3 | |||

| T3 | 10 | 62.5 | 12.7 | 14.8 | 10.2 | .181 | −8.3 | 37.8 | |||

| T4 | 8 | 64.9 | 12.7 | 8.4 | 10.6 | .439 | −14.1 | 30.9 | |||

| TCTSY | T1 | 17 | 67.7 | 18.7 | G: F(1, 37.630) = 15.850; p < .001 | ||||||

| T2 | 12 | 50.8 | 18.6 | T: F(3, 71.380) = 14.023; p < .001 | |||||||

| T3 | 9 | 41.1 | 20.9 | GxT: F(3, 71.339) = 3.456; p = .021 | |||||||

| T4 | 10 | 50.2 | 20.1 |

CAPS at Baseline: F(1, 39.906) = 40.034; p < .001 |

|||||||

Note. G (group); T (time); GxT (group-by-time); M (mean); SD (standard deviation); SE (standard error); Δ (difference); T1 (Baseline); T2 (midway point); T3 (2 weeks post-intervention); T4 (3-months post-intervention); CI (confidence interval); LB (lower bound); UB (upper bound); CAPS-Total Score model and comparison tests performed adjusting for baseline scores.

These are group differences in the change scores from baseline.

Fig. 1.

CAPS (total score) Changes from Baseline (with ≥ 10 point decrease indicated by dashed line).

3.1.1. PTSD diagnosis as indicated by CAPS

The TCTSY group showed greater improvements pre- to post-intervention for losing a PTSD diagnosis. By 2-weeks post-intervention, 44.4 % of the TCTSY group no longer met PTSD criteria compared to 20 % of the CPT group. These effects were sustained at three-months post-intervention, with 50 % of the TCTSY group no longer meeting PTSD criteria compared to only 12.5 % of CPT participants. In the CPT group, the number of participants with a PTSD diagnosis increased at 3-months post-intervention relative to 2-weeks post-intervention, showing a lack of a sustained effect (Table 3).

Table 3.

Participants who Met PTSD diagnostic criteria via CAPS (Time by Group) with longitudinal model results (% within timepoint).

| Timepoint | Baseline | Mid-Txa | 2-weeks Post-Tx | 3-months Post-Tx | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Group | CPT | No | n | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| % | 0 | 0 | 20 | 12.5 | |||

| Yes | n | 22 | 10 | 8 | 7 | ||

| % | 100 | 100 | 80 | 87.5 | |||

| TCTSY | No | n | 2a | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| % | 12.5 | 25 | 44.4 | 50 | |||

| Yes | n | 14 | 9 | 5 | 5 | ||

| % | 87.5 | 75 | 55.6 | 50 |

All participants had a current diagnosis of PTSD; however, two participants reported symptom severity below the clinical threshold for PTSD diagnosis at baseline.

Tx (Treatment).

3.2. PTSD Check List (PCL)

3.2.1. PCL total scores

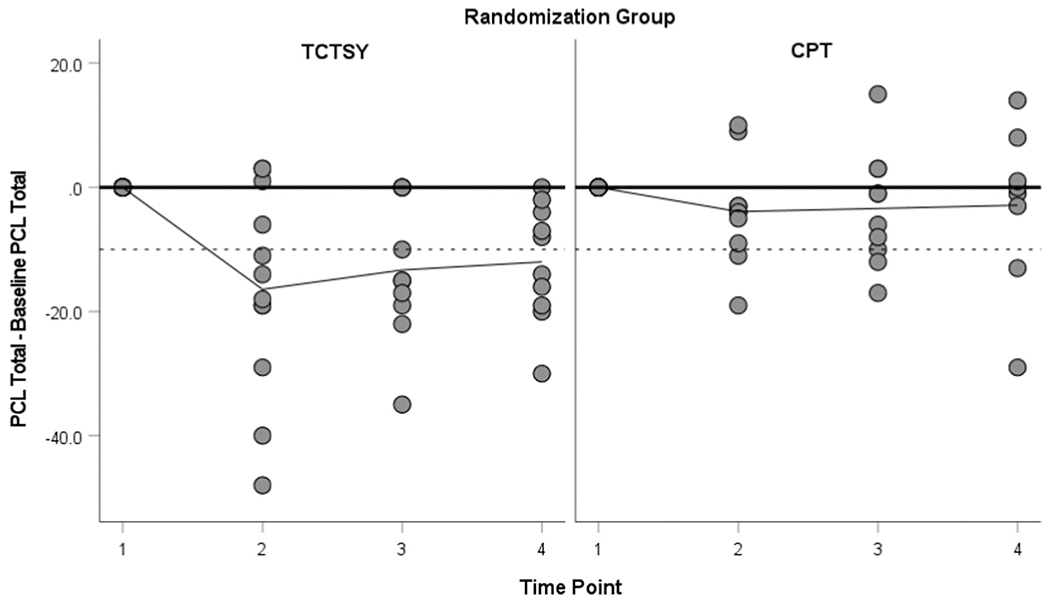

Since there were no significant differences between the two groups at baseline, no adjustment was made for baseline scores as a covariate in the MLM models for PCL. Statistically significant group (p = .003) and time effects (p < .001) were seen for PCL total scores (see Table 4). There were no significant group-by-time effects (p = .129). The percentage of TCTSY participants who achieved a ≥ 10 point decrease in their PCL total scores was 66.7 % (versus 20 % for CPT) at mid-intervention, 70 % (versus 30 % for CPT) at 2-weeks post-intervention and 50 % (versus 25 % for CPT) at 3-months post-intervention. While both groups improved significantly across time, there were no significant differences between the two groups over the course of the study; all confidence intervals for group differences at each time point contained zero. The TCTSY group had a larger percentage of participants who met or exceeded the clinically meaningful decrease of ≥ 10 points for the PCL total score. Fig. 2 shows the range of improvements on their PCL total scores. The dashed line indicates a decrease of 10 points from baseline.

Table 4.

PCL total scores (Time by Group).

| Multilevel Linear Model Effects: | Δ Between Groupsa |

95 % CI |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | SD | G; T; GxT | M | SE | P | LB | UB | |||

| PCL Total | CPT | T1 | 23 | 65.7 | 10.0 | 6.2 | 3.9 | .123 | −1.8 | 14.1 | |

| T2 | 10 | 58.7 | 8.1 | 11.4 | 5.5 | .057 | −0.4 | 23.1 | |||

| T3 | 10 | 58.5 | 14.5 | 10.9 | 6.8 | .127 | −3.4 | 25.2 | |||

| T4 | 8 | 62.9 | 14.3 | 10.8 | 6.5 | .118 | −3.0 | 24.6 | |||

| TCTSY | T1 | 17 | 59.5 | 13.5 | G: F(1,41.291) = 10.116; p = .003 | ||||||

| T2 | 12 | 47.3 | 17.0 | T: F(3,60.481) = 8.468; p < .001 | |||||||

| T3 | 10 | 47.6 | 15.9 | GxT: F(3,60.481) = 1.961; p = .129 | |||||||

| T4 | 10 | 52.1 | 13.3 | ||||||||

Note. G (group); T (time); GxT (group-by-time); M (mean); SD (standard deviation); SE (standard error); Δ (difference); T1 (Baseline); T2 (midway point); T3 (two weeks post-intervention); T4 (-months post-intervention); CI (confidence interval); LB (lower bound); UB (upper bound); PCL model and comparison tests.

These are group differences in the original PCL scores (not adjusted for baseline).

Fig. 2.

PCL (total score) Changes from Baseline (with ≥ 10 point decrease indicated by dashed line).

3.3. PTSD outcomes comparison: pilot study vs. RCT

Given that the pilot study used the DSM-IV-TR version of the CAPS and the RCT used the DSM-5 version of the CAPS, raw change scores were not used for comparison, but Cohen’s dz effect sizes are standardized and could be compared.53 In both the pilot study and RCT interim results,28 the effect sizes for changes in CAPS scores were very large, where most changes had an absolute value (Cohen’s dz > 0.9) both at 2-weeks post-intervention (T3) and at 3-months post-intervention (T4) compared to baseline (T1). This was true for both the TCTSY group and CPT group where negative dz effect sizes indicate CAPS scores improved (decreased) from baseline after completion of treatment sessions (See Table 5).

Table 5.

Changes in CAPS scores from baseline (BL) to each time pointa in both the pilot study and fully powered RCT.

| Cohen’s dz Effect Sizes | CAPS: change from BL |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pilot Study | Full RCT | |||

| CPT | T2 - T1 | Mid - BL | 0.56 | −0.90 |

| T3 - T1 | 2 wk - BL | −1.70 | −0.99 | |

| T4 - T1 | 3 m - BL | −0.70 | −1.44 | |

| TCTSY | T2 - T1 | Mid - BL | −0.90 | −1.09 |

| T3 - T1 | 2 wk - BL | −0.99 | −1.14 | |

| T4 - T1 | 3 m - BL | −0.92 | −1.17 | |

T1 (Baseline); T2 (midway point); T3 (two weeks post-intervention); T4 (-months post-intervention).

4. Discussion

In this pilot study with women Veterans with PTSD related to MST, the clinically and statistically significant improvements in PTSD symptom severity seen in the TCTSY group are generally consistent in pattern and degree with those of the subsequent RCT interim findings,28 adding strength to the existing research examining yoga as a clinical intervention for PTSD. The large effect sizes seen at each time point (0.90–0.99) were slightly lower than the effect sizes reported in the RCT interim findings (1.09–1.17). Yoga studies have shown promising results using a variety of yoga interventions, for example, Sciarrino et al. reported a weighted mean average effect size of 0.48 in a review and synthesis of studies of yoga for PTSD.54 However, a meta-analysis of seven yoga RCTs (N = 284) for PTSD demonstrated low quality evidence for clinically meaningful change, compared to no treatment and very low evidence for attention control conditions.26 Specifically, Cramer et al. reported low-quality evidence for clinically meaningfully differences on PTSD symptoms with yoga compared to no treatment and very low evidence for comparable effects of yoga and attention control interventions.26 To our knowledge, no studies of yoga for PTSD have used an evidence-based treatment as a comparison condition prior to or since the pilot study reported here and RCT interim findings.28 The pilot study reported here and the subsequent RCT add significantly to the evidence by demonstrating clinically meaningfully change and by using a gold-standard psychotherapy, CPT, as a comparator. In addition to the strength of the effect sizes in this study and the subsequent RCT, there are clinically relevant findings that can inform subsequent pilot studies and RCTs in this field.

4.1. PTSD symptom trajectory

In this study, the group-by-time effects illustrated three patterns of change: 1) TCTSY participants showed improvement from baseline to mid-intervention (versus baseline to 2-weeks post-intervention for CPT); 2) there were higher percentages of TCTSY participants who achieved clinically meaningful improvements from baseline to mid-treatment compared to their CPT counterparts; and 3) TCTSY participants sustained improvements at 3-months post-intervention follow up when CPT participants were endorsing a rise in symptoms. In the full RCT, the PTSD symptom trajectory in the TCTSY group was similar, however the CPT group improved by mid-intervention (though to a lesser degree than TCTSY), and continued to improve in subsequent time points, with comparable final PTSD symptom improvement to TCTSY. These findings indicate that as an alternative treatment or a precursor to trauma-focused therapy, TCTSY may reduce attrition by increasing motivation due to symptom reduction early in care (between baseline and mid-intervention for TCTSY participants). The symptom trajectory with TCTSY may not include the transient symptom exacerbation that can accompany cognitively-based EBPs prior to symptom improvement, as seen in the pilot study, and may contribute to treatment attrition. Notably, the role of symptom exacerbation and the recovery trajectory of CPT found here echoes that of previous studies that have examined this phenomenon in CPT.55,56 These findings also support the theory that the embodied approach of TCTSY shows promise as a mechanism to healing that may have a sustained effect, which could add to the current primarily cognitive mechanistic approaches that may be effective for individuals recovering from sexual trauma.

4.2. Treatment attrition and completion

It is important to note that in both the pilot and full RCT studies, although CPT had large within group effect sizes, the high attrition rates and low treatment completion rates demonstrate the limitations of this current first-line treatment for PTSD. Higher study retention and intervention completion rates in TCTSY compared to CPT support the study rationale that additional treatment options are needed to address the gaps in trauma-focused psychotherapies’ acceptability and treatment dropout among women Veterans with PTSD related to MST. While EBPs have demonstrated effectiveness, high drop-out rates and incomplete symptom remission render most patients who attempt or complete these modalities without effective treatment.15,57

4.3. Patient treatment preference in PTSD clinical trials and clinical care

The decrease in attrition rates in both groups from the pilot study to the full RCT may be the result of offering a cross-over option in the RCT, thus, participants knew they would have the option of their preferred treatment if they were randomized to their non-preferred treatment. This has implications for future study designs and for clinical care. The partially randomized patient preference trial design (RPPT) includes separate cohorts – those with a preference choose their treatment arm and those without a strong preference are randomized to treatment. Wasmann et al., in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, reported that inclusion of patient preference in clinical trials using a RPPT design dramatically increased participation rates (> 95 % in 14 trials) versus RCT refusal rate (> 50 % in 26 trials), lowered lost to follow up and cross-over rates, and yielded comparable primary outcomes between both preference and randomized cohorts.58 The shared decision making process (SDMP) is defined as a process of helping patients make informed treatment decisions where providers share the best available evidence about treatment options and assist patients in identifying what matters most to them.59 In the clinical realm, SDMP is recommended in the VA/DoD PTSD treatment guidelines,60 and the VA’s National Center for PTSD online PTSD treatment decision aid.61 Thus, inclusion of patient preference in treatment choice in both clinical trials and clinical care are likely to lead to higher treatment initiation and completion rates, with potentially higher effectiveness rates. This approach would directly address the significant gap in PTSD treatment effectiveness and completion.

Finally, the majority African American women sample in this yoga study is unique and highly important. Yoga scholarship, practitioners, and media portrayals of yoga lack representative populations of African Americans, and most studies of yoga for PTSD in Veterans have predominantly male samples.62,63 While there are first-person accounts and a growing body of literature regarding racial and ethnic minorities’ attitudes about yoga and barriers to accessing yoga, to our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate yoga as a clinical intervention for PTSD in a largely African American women sample.64,65 Additionally, our sample had multiple identities to navigate, including their Veteran status, PTSD diagnosis, and for some, sexual minority status. The efficacy and effectiveness of yoga for people with intersecting marginalized identities warrants further investigation.

4.4. Limitations

The sample size, while providing adequate power to detect large effect sizes, was small. These findings were considered exploratory in nature from the outset of this study, however they are consistent with the findings of the subsequent study. It is possible that completing baseline assessment after informing participants of their randomized group assignment impacted symptom severity at baseline. These unexpected differences in PTSD symptoms at baseline required statistical procedures to control for them prior to conducting outcomes analyses on these variables. Differences in attrition could be related to comparing a popular and novel intervention (yoga) to a traditional psychotherapy; they also may be driven by women with avoidance or higher PTSD symptom severity dropping out of CPT.

Future research, beyond that conducted by this study team, would be well served to replicate this study with a larger sample size for more robust analyses, examining covariates, such as chronic pain, sleep disturbances and sleep disorders, and comorbid psychiatric disorders. Replication would be beneficial if completed in various regions of the US and globally, as there may be regional differences as to the population that may impact acceptability, feasibility, and effectiveness of a yoga intervention. Study designs, such as RPPT, that include patient preference in treatment will help to overcome recruitment challenges and study attrition, while maintaining scientific rigor to establish effectiveness. Finally, TCTSY is unstudied with men, civilian or veterans, who experienced sexual trauma. This is a significant gap in the literature.

5. Conclusions

Women Veterans with PTSD related to MST reported significant improvements in overall PTSD symptom severity following TCTSY, commensurate with longitudinal changes found in a first-line, cognitively based psychotherapy, CPT. Women who participated in TCTSY demonstrated benefits sooner and sustained those benefits longer compared to those in CPT. These pilot results, in addition to results from the subsequent RCT, suggest that integration of TCTSY as treatment modality for women Veterans with PTSD related to MST may provide a PTSD treatment option with earlier symptom improvement, higher retention, and sustained effect – clinical outcomes that are urgently needed for this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the women Veterans who participated in this study for their service to their country and for their study participation. We would also like to thank the CPT therapists and TCTSY facilitators who provided the interventions in this study.

Funding Statement

This material is based upon work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service, Grant # 1I01HX001087-01A1 (PI: Ursula Kelly). Preparation of this manuscript was supported by Grant no. K12 HS026370 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (BZ).

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Appendix A.: Supporting information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2022.102850.

References

- 1.U.S. Census Bureau. Those who Served: America’s Veterans from World War II to the War on Terror; 2020. 〈https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/demo/acs-43.pdf〉.

- 2.VA. VetPop2018: A Brief Description (U. S. D. of V. Affairs. (ed.)). Veteran Population Projections Model (VetPop2018). National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics; 2018. 〈https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/Demographics/New_Vet_pop_Model/VP_18_A_Brief_Description.pdf〉. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barth SK, Kimerling RE, Pavao J, et al. Military sexual trauma among recent veterans: correlates of sexual assault and sexual harassment. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(1):77–86. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimerling R, Street AE, Pavao J, et al. Military-related sexual trauma among Veterans Health Administration patients returning from Afghanistan and Iraq. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(8):1409–1412. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.171793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Street AE, Shin MH, Marchany KE, McCaughey VK, Bell ME, Hamilton AB. Veterans’ perspectives on military sexual trauma-related communication with VHA providers. Psychol Serv. 2019. 10.1037/ser0000395 [Advance online publication]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson LC. The prevalence of military sexual trauma: a meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence Abus. 2018;19(5):584–597. 10.1177/1524838016683459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang H, Dalager N, Mahan C, Ishii E. The role of sexual assault on the risk of PTSD among Gulf War veterans. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15(3):191–195. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly UA, Evans DD, Baker H, Noggle Taylor J. Determining psychoneuroimmunologic markers of Yoga as an intervention for persons diagnosed with PTSD: a systematic review. Biol Res Nurs. 2018;20(3):343–351. 10.1177/1099800417739152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pulverman CS, Christy AY, Kelly UA. Military sexual trauma and sexual health in women Veterans: a systematic review. Sex Med Rev. 2019;7(3):393–407. 10.1016/j.sxmr.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zinzow HM, Grubaugh AL, Monnier J, Suffoletta-Maierle S, Frueh BC. Trauma among female veterans: a critical review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2007;8(4):384–400. 10.1177/1524838007307295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schottenbauer MA, Glass CR, Arnkoff DB, Tendick V, Gray SH. Nonresponse and dropout rates in outcome studies on PTSD: review and methodological considerations. Psychiatry. 2008;71(2):134–168. 10.1521/psyc.2008.71.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steenkamp MM, Litz BT, Hoge CW, Marmar CR. Psychotherapy for military-related PTSD: a review of randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2015;314(5):489–500. 10.1001/jama.2015.8370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berke DS, Kline NK, Schuster J, et al. Predictors of attendance and dropout in three randomized controlled trials of PTSD treatment for active-duty service members. Behav Res Ther. 2019;118(2018):7–17. 10.1016/j.brat.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eftekhari A, Crowley JJ, Rosen CS. Predicting treatment dropout among Veterans receiving prolonged exposure therapy. Psychol Trauma: Theory Res Pract Policy. 2020;12(4):405–412. 10.1037/tra0000484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imel ZE, Laska K, Jakupcak M, Simpson TL. Meta-analysis of dropout in treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychoogyl. 2013;81(3):394–404. 10.l037/a0031474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zayfert C, Deviva JC, Becker C, Pike JL. Exposure utilization and completion of cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD in a “real world” clinical practice. J Trauma Stress: Publ Int Soc Trauma Stress Stud. 2005;18(6):637–645. 10.1002/jts.20072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor SL, Hoggatt KJ, Kligler B. Complementary and integrated health approaches: what do Veterans use and want. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(7):1192–1199. 10.1007/s11606-019-04862-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Veterans Affairs. Department of Veterans Affairs Fiscal Years 2022–28 Strategic Plan. Washington, D.C.; 2022. Retrieved from (https://www.va.gov/oei/docs/va-strategic-plan-2022-2028.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Office of Patient Centered Care, Cultural Transformation (OPCC&CT) C. Library of Research Articles on Veterans and Complementary and Integrative Health Therapies. The VA Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation’s (OPCC&CT) and VA Complementary and Integrative Health Evaluation Center’s (CIHEC); 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Directive 1137: Provision of Complementary and Integrative Health; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chopin SM, Sheerin CM, Meyer BL, Sheerin CM, Meyer BL. Yoga for warriors: An intervention for Veterans with comorbid chronic pain and PTSD. Psychol Trauma: Theory, Res Pract Policy. 2020. 10.1037/tra0000649 [Advance online publication]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cushing RE, Braun KL. Mind-body therapy for military Veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. J Altern Complement Med. 2017;24(2):106–114. 10.1089/acm.2017.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis LW, Schmid AA, Daggy JK, et al. Symptoms improve after a yoga program designed for PTSD in a randomized controlled trial with Veterans and civilians. Psychol Trauma: Theory Res Pract Policy. 2020. 10.1037/tra0000564 [Advance online publication]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaccari B, Callahan ML, Storzbach D, et al. Yoga for Veterans with PTSD: cognitive functioning, mental health, and salivary cortisol. Psychol Trauma: Theory Res Pract Policy. 2020. 10.1037/tra0000909 [Advance online publication]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coeytaux RR, McDuffie J, Goode A, et al. VA Evidence-Based Synthesis Program Reports. Evidence Map of Yoga for High-Impact Conditions Affecting Veterans. Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cramer H, Anheyer D, Saha FJ, Dobos G. Yoga for posttraumatic stress disorder – a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:72. 10.1186/sl2888-018-1650-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strauss JL, Coeytaux R, McDuffie J, Nagi A, Williams JW Jr. VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program Reports. Efficacy of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Therapies for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly U, Haywood T, Segell E, Higgins M. Trauma-sensitive yoga for post-traumatic stress disorder in women Veterans who experienced military sexual trauma: interim results from a randomized controlled trial. J Alter Complement Med. 2021;27(S1):S45–s59. 10.1089/acm.2020.0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Desveaux L, Lee A, Goldstein R, Brooks D. Yoga in the management of chronic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Care. 2015;53(7):653–661. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duan-Porter W, Coeytaux RR, McDuffie JR, et al. Evidence map of yoga for depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13(3):281–288. 10.1123/jpah.2015-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emerson D, Hopper E. Overcoming Trauma through Yoga: Reclaiming Your Body. North Atlantic Books; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCall MC, Ward A, Roberts NW, Heneghan C. Overview of systematic reviews: yoga as a therapeutic intervention for adults with acute and chronic health conditions. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2013;2013, 945895. 10.1155/2013/945895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emerson D Trauma-sensitive yoga: principles, practice, and research. Int J Yoga Ther. 2009;19(1):123–128. 10.17761/ijyt.19.l.h6476p8084l22160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.West J, Liang B, Spinazzola J. Trauma Sensitive Yoga as a complementary treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: a qualitative descriptive analysis. Int J Stress Manag. 2017;24(2):173–195. 10.1037/str0000040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaccari B, Sherman ADF, Higgins M, Ann Kelly U. Trauma Center Trauma-Sensitive Yoga Versus Cognitive Processing Therapy for Women Veterans With PTSD Who Experienced Military Sexual Trauma: A Feasibility Study. J. Am. Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2022. 10.1177/10783903221108765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Resick PA, Galovski TE, Uhlmansiek MO, Scher CD, Clum GA, Young-Xu Y. A randomized clinical trial to dismantle components of cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in female victims of interpersonal violence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(2):243–258. 10.1037//0022-006X.76.2.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Resick PA, Monson CM, Chard KM. Cognitive Processing Therapy: Therapist’s Manual. Department of Veterans’ Affairs; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cahill SP, Foa EB. Psychological theories of PTSD. Handb PTSD: Sci Pract. 2007:55–77. [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Psychological Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Of Mental Disorders (4th ed., Text Revision). Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 40.American Psychological Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Of Mental Disorders-5 (5 ed.). Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weathers FW, Keane TM, Davidson JRT. Clinician-administered PTSD Scale: a review of the first ten years of research. Depress Anxiety. 2001;13(3):132–156. 10.1002/da.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL). Behav Res Ther. 1996;34(8):669–673. 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.NCSS L. PASS 2020 Power Analysis and Sample Size Software; 2020. ncss.com/software/pass.

- 44.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Longitudinal Data analysis 451. John Wiley & Sons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wasserstein RL, Schirm AL, Lazar NA. Moving to a world beyond “p < 0.05”. Am Stat. 2019;73:0–19. 10.1080/00031305.2019.1583913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Monson CM, Gradus JL, Young-Xu Y, Schnurr PP, Price JL, Schumm JA. Change in posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: do clinicians and patients agree. Psychol Assess. 2008;20(2):131–138. 10.1037/1040-3590.20.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Foy DW, et al. Randomized trial of trauma-focused group therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: results from a Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(5):481–489. 10.1001/archpsyc.60.5.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Corp IBM. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (25.0). IBM Corp; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khan AJ, Holder N, Li Y, et al. How do gender and military sexual trauma impact PTSD symptoms in cognitive processing therapy and prolonged exposure? J Psychiatr Res. 2020;130:89–96. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maguen S, Holder N, Madden E, et al. Evidence-based psychotherapy trends among posttraumatic stress disorder patients in a national healthcare system, 2001–2014. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(4):356–364. 10.1002/da.22983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Resick PA, Wachen JS, Mintz J, et al. A randomized clinical trial of group cognitive processing therapy compared with group present-centered therapy for PTSD among active duty military personnel. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(6):1058–1068. 10.1037/ccp0000016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cohen J Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2 ed. Academic Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sciarrino NA, DeLucia C, O’Brien K, McAdams K. Assessing the effectiveness of yoga as a complementary and alternative treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder: a review and synthesis. J Altern Complement Med. 2017;23(10):747–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Larsen SE, Mackintosh MA, La Bash H, et al. Temporary PTSD symptom increases among individuals receiving CPT in a hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial: potential predictors and association with overall symptom change trajectory. Psychol Trauma: Theory Res Pract Policy. 2020. 10.1037/tra0000545 [Advance online publication]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Larsen SE, Wiltsey Stirman S, Smith BN, Resick PA. Symptom exacerbations in trauma-focused treatments: associations with treatment outcome and non-completion. Behav Res Ther. 2016;77:68–77. 10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kehle-forbes SM, Meis LA, Spoont MR, et al. Treatment initiation and dropout from prolonged outpatient clinic treatment initiation and dropout from prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy in a VA outpatient clinic. Psychol Trauma: Theory Res Pract Policy. 2016;8(1):107–114. 10.1037/tra0000065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wasmann KA, Wijsman P, van Dieren S, Bemelman W, Buskens C. Partially randomised patient preference trials as an alternative design to randomized controlled trials: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10), e031151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Disorder, Version 3.0; 2017.

- 61.Department of Veterans Affairs, NCfp. PTSD Treatment Decision Aid; n.d. Retrieved from (https://www.ptsd.va.gov/apps/decisionaid/).

- 62.Burnett-Zeigler I, Schuette S, Victorson D, Wisner KL. Mind-Body approaches to treating mental health symptoms among disadvantaged populations: a comprehensive review. J Altern Complement Med. 2016;22(2):115–124. 10.1089/acm.2015.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Webb JB, Rogers CB, Thomas EV. Realizing Yoga’s all-access pass: a social justice critique of westernized yoga and inclusive embodiment. Eat Disord. 2020;28(4):349–375. 10.1080/10640266.2020.1712636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bondy D Confessions of a fat, black yoga teacher. In: Klein M, Guest-Jelly A, eds. Yoga and Body Image: 25 Personal Stories About Beauty, Bravery & Loving Your Body. Woodbury, MN: Llewellyn Publications; 2014:73–81. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Spadola CE, Rottapel R, Khandpur N, et al. Enhancing yoga participation: a qualitative investigation of barriers and facilitators to yoga among predominantly racial/ethnic minority, low-income adults. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;29:97–104. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Further reading

- 66.Price M, Spinazzola J, Turner J, Suvak M, Emerson D, van der Kolk B. Effectiveness of an extended yoga treatment for women with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2017;23(4):300–309. 10.1089/acm.2015.0266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.